Abstract

This paper aims to assess the rationales for export taxes in the context of a food crisis. First, we summarize the effects of export taxes using both partial and general equilibrium theoretical models. When large countries aim to maintain constant domestic food prices, in the event of an increase in world agricultural prices, the optimal response is to decrease import tariffs in net food-importing countries and to increase export tariffs in net food-exporting countries. The latter decision improves national welfare, while the former reduces national welfare: this is the price that must be paid to keep domestic food prices constant. Small net food-importing countries are harmed by both decisions, while small net food-exporting countries gain from both. Second, we illustrate the costs of a lack of regulation and cooperation surrounding such policies in a time of crisis using a global computable general equilibrium (CGE) model, mimicking the mechanisms that appeared during the recent food price surge (2006–2008). This model illustrates the interdependence of trade policies, as well as how a process of retaliation and counter-retaliation (increased export taxes in large net food-exporting countries and reduced import tariffs in large net food-importing countries) can contribute to successive augmentations of world agricultural prices and harm small net food-importing countries. We conclude with a call for international regulation, in particular because small net food-importing countries may be substantially harmed by those policies that amplify the already negative impact of a food crisis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It has also been argued that export taxes on commodities (cocoa, oil) have been administrated in a very convoluted way in several developing countries (for example, Côte d’Ivoire) and have fostered corruption, as this resource is less monitored than other taxes paid by local customers/constituencies.

The main reason is that we are interested in what happens to demand for the agricultural good. There are some equivalence theorems that show that in a 2 countries-2 goods model, the imposition of an export tax is equivalent to an import tax (Lerner 1936). We could also consider that import tariffs on the industrial good are bound at 0.

In particular to obtain (7), it has to be reminded that: \( p_{2} = p\left( {1 + t_{2} } \right)\,{\text{ and }}\,E_{2}^{I} = pM_{2}^{A} \).

We can easily derive a relation between the reciprocal demand elasticity and the parameters \( s_{2}^{C} \), e 2 , m 2 , and d 2 defined previously.

The design of optimal export taxes requires the estimation of consumption, production, and trade elasticities. Broda et al. (2006) find evidence that non–WTO members have market power and implement relatively high tariffs compared to WTO members. Warr (2001) concludes that available econometric estimates for the world demand elasticity of rice facing Thailand imply optimal export taxes ranging from 25 to 100%. This assessment may lead to false interpretations; Bautista (1996) gives an example in which the Philippine government implemented an export tax on copra and coconut oil based on the principle that the country represented a large share of the world market for these products and faced a “negative elasticity” in world export demand. In fact, this evaluation did not take into account substitutability with other vegetable oils and the Philippines’ consequent low share of the world market. Moreover, demand and supply elasticities may change over time; consequently a country may gain in the short run while losing in the longer run.

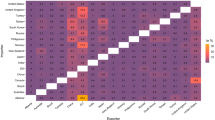

The model is also based on low Armington elasticities (these are GTAP elasticities—see Hertel et al. 2007) as compared to other models like LINKAGE from the World Bank. A sensitivity analysis has been undertaken in order to conduct the same analysis with higher elasticities. These results are given in a footnote in Sect. 3.2.

See the statements made during G-20 Seoul meetings in November 2,010 (http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/biz/2010/10/301_74514.html).

This does not represent an evaluation of the analysis conducted in Sect. 2.2 since we do not assess the consequences of the implementation of increased export taxes and reduced import duties starting from free trade. The objective of this section is to evaluate the economic consequences of trade policies (either through increased export taxes or reduced import taxes designed to keep domestic prices constant) on countries’ real income, since we think that these policies have been adopted during the food crisis. In that sense, we add new distortions to a world trading system with initial distortions. We could study how close initial policies are to their optimal level, but it would represent a new object of research.

In the GTAP7 database (base year 2004), the EU-27 position on wheat is atypical with a balanced position. Therefore, we do not treat the European Union as a net exporter (or a net importer).

In a scenario in which export and import taxes are both endogenous, countries enter a spiral of never-ending escalation of export taxes and import subsidies because on the importing countries’ side, the governments have no fiscal constraints and can finance the subsidies using a lump-sum transfer from households.

A sensitivity analysis has been carried out. It focuses on the ET scenario under which wheat-exporting countries impose an export tax in order to maintain domestic price constant. Two options are considered: either Armington elasticities are doubled, or supply elasticities are doubled. Results are not much modified. Evolution of world prices and countries’ real incomes are very close to our central scenario. Export taxes that governments have to implement in order to keep domestic price constant are slightly different, but only differ from taxes in the central scenario by 0.6–4.6 points. The maximum difference occurs in the case of Russia’s export tax (24.9% in the central scenario) when Armington elasticities are doubled. Detailed results of this sensitivity analysis may be requested from the authors.

As explained in Sect. 4.1 above, we used the static version of the MIRAGE model.

Kim (2010) states that amongst WTO members imposing export duties, 21 are least developed countries, 40 are middle income countries and only 4 are rich countries.

The European Union’s proposal is available on the WTO website (TN/MA/W/11/add. 6).

References

Amiruddin, M. N. (2003). Palm oil products exports, prices and export duties: Malaysia and Indonesia compared. Oil Palm Industry Economic Journal, 3(2), 15–20.

Bautista, R. M. (1996). Export tax as income stabiliser under alternative policy regimes: The case of Philippine copra. In E. de Dios & R. V. Fabella (Eds.), Choice, growth and development: Emerging and enduring issues. Quezon City, The Philippines: University of the Philippines Press.

Bchir, H., Decreux, Y., Guerin, J.-L., & Jean, S. (2002). MIRAGE, a computable general equilibrium model for trade policy analysis. (CEPII Discussion Papers 2002-17). Paris: Centre d’Etudes Prospectives et d’Informations Internationales.

Bickerdike, C. F. (1906). The theory of incipient taxes. Economic Journal, 16(64), 529–535.

Bouët, A., & Laborde Debucquet, D. (2010). The economics of export taxation in the context of a food crisis: A theoretical and CGE-approach contribution. (IFPRI Discussion Paper 00994). Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

Boumellassa, H., Laborde Debucquet, D., & Mitaritonna, C. (2009). A consistent picture of the protection across the world in 2004: MAcMapHS6 version 2. (IFPRI Discussion Paper 903). Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

Broda, C., Limao, N., & Weinstein, D. (2006). Optimal tariffs: The evidence. (NBER Working Paper 12033). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Corden, W. M. (1971). The theory of protection. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Crosby, D. (2008). WTO legal status and evolving practice of export taxes. Bridges, 12(5), 3–4.

Deardorff, A. V., & Rajaraman, I. (2005). Can export taxation counter monopsony power? (RSIE Discussion Paper 541). Ann Arbor, MI: Research Seminar in International Economics, University of Michigan.

Decreux, Y., & Valin, H. (2007). MIRAGE, updated version of the model for trade policy analysis: Focus on agriculture and dynamics. (CEPII Discussion Papers 15). Paris: Centre d’Etudes Prospectives et d’Informations Internationales.

Diamond, P. A. (1975). A many-person Ramsey rule. Journal of Public Economics, 4(4), 335–342.

Headey, D. (2010). Rethinking the global food crisis: The role of trade shocks. (IFPRI Discussion Paper 00958). Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

Headey, D., & Fan, S. (2010). Reflections on the global food crisis: How did it happen? How has it hurt? And how can we prevent the next one? Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

Hertel, T., Hummels, D., Ivanic, M., & Keeney, R. (2007). How confident can we be of CGE-based assessments of free trade agreements? Economic Modelling, 24(4), 611–635.

Hoddinott, J., Maluccio, J. A., Behrman, J. R., Flores, R., & Martorell, R. (2008). Effect of a nutrition intervention during early childhood on economic productivity in Guatemalan adults. The Lancet, 371(9610), 411–416.

Johnson, H. G. (1953). Optimum tariffs and retaliation. Review of Economic Studies, 21(2), 142–153.

Kim, J. (2010). Recent trends in export restrictions on raw materials. In The economic impact of export restrictions on raw materials. (Trade Policy Studies, 13–57). Paris: OECD.

Lerner, A. P. (1936). The symmetry between import and export taxes. Economica, 3(11), 306–313.

Martin, W., & Anderson, K. (2010). Trade distortions and food price surges. Paper for the World Bank-UC Berkeley conference on agriculture for development—revisited, Berkeley, 1–2 October, 2010.

Mitra, S., & Josling, T. (2009). Agricultural export restrictions: Welfare implications and trade disciplines. IPC position paper, agricultural and rural development series. Washington, DC: International Food and Agricultural Trade Policy Council.

Narayanan, B. G., & Walmsley, T. L. (Eds.) (2008). Global trade, assistance, and production: The GTAP 7 data base. West Lafayette, IN: Center for Global Trade Analysis, Purdue University.

OECD (2010). Policy responses in emerging economies to international agricultural commodity price changes, TAD/CA/APM/WP(2010)13.

Piermartini, R. (2004). The role of export taxes in the field of primary commodities. (WTO Discussion Paper 4). Geneva: World Trade Organization.

Polovinkin, S. (2010). Food crisis and food security policies in West Africa: An inventory of West African countries’ policy responses during the 2008 food crisis [internet]. Version 9. Knol. May 3, 2010. Available from: http://www.knol.google.com/k/sergey-polovinkin/food-crisis-and-food-security-policies/cju5lr97z6h4/32.

Raja, K. (2006). Clash in NAMA talks on proposed export-tax rules. SUNS, June 1, http://www.twnside.org.sg/title2/twninfo418.htm.

Ramsey, F. P. (1927). A contribution to the theory of taxation. Economic Journal, 37(145), 47–61.

Warr, P. G. (2001). Welfare effects of an export tax: Thailand’s rice premium. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 83(4), 903–920.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants of a workshop organized at OECD on October 30, 2009 and of a seminar organized at IFPRIMTID in Washington DC on April 10, 2010, and in particular Jeonghoi Kim, David Tarr, Franck Von Tongeren, and Maximo Torero for useful comments on an earlier version. Two anonymous reviewers have been also very helpful. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

About this article

Cite this article

Bouët, A., Laborde Debucquet, D. Food crisis and export taxation: the cost of non-cooperative trade policies. Rev World Econ 148, 209–233 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-011-0108-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-011-0108-8