Abstract

There has been great focus in the recent trade theory literature on the introduction of firm heterogeneity into trade models. This introduction has highlighted the importance of the entry/exit decision of firms in response to changes in trade barriers. However, it is typical in many of these models to use iceberg transport costs as a general form of trade barriers that can be interchangeable with ad valorem tariffs. I show that this is not always an appropriate conclusion. Specifically, I illustrate that profit for an exporter is more elastic in response to tariffs than iceberg transport costs, which affects the entry/exit decision of firms. This has implications for welfare analysis and empirical specifications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Broda and Weinstein (2006) show that growth in product variety from US imports has been an important source of gains from trade.

“Iceberg” transport costs are defined as a firm needing to ship more than one unit of good in order for one unit to arrive; the additional units “melt” away.

Similarly, it may not be appropriate to simply “waste” tariff revenue in order to model iceberg transport costs as Jørgensen and Schröder (2008) does.

See, for example, Irarrazabal et al. (2010) who show that welfare gains from reducing per-unit frictions are higher than that of reducing iceberg frictions.

The use of fixed cost heterogeneity results in all firms of the same “type” (either pure domestic or exporting) to charge the same price. This obviously affects firm demand and profits which in turn affects the entry and exit decision. However, this does not eliminate the differences between iceberg transport costs and ad valorem tariffs as trade barriers.

See also Becker (2009).

Chaney (2008) points out that relaxing this assumption would reinforce his results.

It should be noted that income does change in response to changes in trade barriers and this income change affects welfare. However, it will all be through changes in consumption/production of the numeraire and not affect the heterogeneous goods sector.

The term ‘beachhead’ costs was coined by Baldwin (1988).

Note that if tariffs are set to zero or the firm is domestic the prices, \(p_k(i)=p_k^c(i)\), are equivalent. Furthermore, recall that under perfect competition, the price of y is equal to one.

One interpretation of the model is that firms are owned by entrepreneurs and that firm profits accrue to these entrepreneurs. In my representative agent setting, these profits would simply enter national income in the same way that wages do, therefore I discuss the model in terms of firms to avoid needless jargon. This interpretation is similar to that of Yu (2002). Additionally, it is common in heterogeneous firm models to have entrepreneurs draw from a distribution of productivities (often at a cost). The advantage to that approach is that it permits multiple varieties to have the same productivity. The cost, however, is one of added complexity and additional assumptions since modelers are often forced to parameterize this distribution (the Pareto distribution is a common choice). Here, my assumption of unique variety/productivity combinations aids greatly in the presentation of my results in the simplest, most tractable fashion.

The assumption that γ > 1 is fairly standard (e.g. Melitz 2003) and important. It is rarely seen that a firm (particularly not a multinational) that sells abroad but not at home and as long as expenditure on the heterogeneous good are not too different, this ensures that will never happen. Moreover, it does so by allowing profits in both countries to be additively separable, which is quite attractive. Relaxing this assumption, but restricting the firm to sell at home before exporting would only complicate the model without changing the qualitative results.

This assumption is only done for notational ease. In order to investigate asymmetric changes in transport costs, one only needs to add a country subscript to σ.

Since preferences are identical across both countries, it follows that the total expenditure on the heterogeneous good is equal to μ in both markets. Furthermore, recall that technologies and the mass of entrepreneurs are also identical across countries. This, along with γ > 1, is sufficient to ensure that a firm which exports will always serve the domestic market.

Note that, in perfect competition, price equals marginal cost and the standard result of iceberg costs having the same effect as an ad valorem tariff still holds.

This will be shown later.

Recall Eq. (10).

Note though, that t j and σ affect p c j in the exact same way, as shown by Eq. (10).

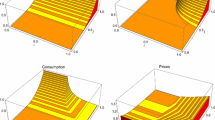

For numerical simulations, I assume that the function f(i) is linear.

This nice simplification stems from the utility specification used.

Note that \(N_k=i_{kD}+i_{jX}\).

Note that this is the case when ∂N k /∂σ < 0.

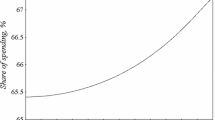

For purposes of comparison, one logical choice would be to evaluate the comparative statics when the trade restrictions are equal. Let \(\sigma=t_k=\rho\geq1\), then

$$ \left.\frac{\partial N_k}{\partial t_k}\right|_{\sigma=t_k=\rho}= \left.\frac{\partial N_k} {\partial\sigma}\right|_{\sigma=t_k=\rho}+\left(\frac{\gamma} {\rho}\right)\left.\frac{\partial N_k} {\partial\gamma}\right|_{\sigma=t_k=\rho}. $$Recall, from Corollary 1, that if \(\varrho_\sigma\leq0\Rightarrow\varrho_{t_k}<0\). Thus, in this case, if \((\varrho_{t_k}-\varrho_\sigma)<0\) then \(|\varrho_{t_k}|>|\varrho_\sigma|\).

Again, from Corollary 1, it follows that if \(\varrho_{t_k}\geq0\Rightarrow\varrho_\sigma>0\). Thus, in this case, if \((\varrho_{t_k}-\varrho_\sigma)<0\) then \(|\varrho_\sigma|>|\varrho_{t_k}|\).

Detailed derivations are available upon request.

References

Arkolakis, C. (2008). Market penetration costs and the new consumers margin in international trade. (NBER Working Paper No. 14214).

Baldwin, R. (1988). Hysteresis in import priced: The beachhead effect. American Economic Review, 78(4), 773–785.

Baldwin, R., & Forslid, R. (2010). Trade liberalization with heterogeneous firms. Review of Development Economics, 14(2), 161–176.

Becker, J. (2009). Taxation of foreign profits with heterogeneous multinational firms. (CESifo Working Paper Series No. 2899).

Broda, C., & Weinstein, D. (2006). Globalization and the gains from variety. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121(2), 541–585.

Chaney, T. (2008). Distorted gravity: The intensive and extensive margins of international trade. American Economic Review, 98(4), 1707–1721.

Chor, D. (2009). Subsidies for FDI: Implications from a model with heterogeneous firms. Journal of International Economics, 78(1), 113–125.

Cole, M. A., Elliot, R., & Virakul, S. (2010). Firm heterogeneity, origin of ownership and export participation. World Economy, 33(2), 264–291.

Cole, M. T. (2010). Distorted trade restrictions: A comment on “distorted gravity”. (Working Paper No. 201019). University College Dublin.

Davies, R., & Eckel, C. (2010). Tax competition for heterogeneous firms with endogenous entry. American Economic Review, 2(1), 77–102.

Demidova, S., & Rodríguez-Clare, A. (2009). Trade policy under firm-level heterogeneity in a small economy. Journal of International Economics, 78(1), 100–112.

Eaton, J., Kortum, S., & Kramarz, F. (2008). An anatomy of international trade: Evidence from French firms. (NBER Working Paper No. 14610).

Friedman, T. (2007) The world is flat: A brief history of the twenty-first century. New York: Douglas & McIntyre.

Irarrazabal, A., Moxnes, A., & Opromolla, L. (2010). The tip of the iceberg: Modeling trade costs and implications for intra-industry reallocation. (CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP7685).

Jean, S. (2002). International trade and firms’ heterogeneity under monopolistic competition. Open Economies Review, 13(3), 291–311.

Jørgensen, J., & Schröder, P. (2006). Tariffs and firm-level heterogeneous fixed export costs. Contributions to Economic Analysis & Policy, 5(1), 1–16.

Jørgensen, J., & Schröder, P. (2008). Fixed export cost heterogeneity, trade and welfare. European Economic Review, 52(7), 1256–1274.

Krugman, P. (1979). Increasing returns, monopolistic competition, and international trade. Journal of International Economics, 9(4), 469–479.

Krugman, P. (1980). Scale economies, product differentiation, and the pattern of trade. American Economic Review, 70(5), 950–959.

Lawless, M., & Whelan, K. (2008). Where do firms export, how much, and why? (Research Technical Paper 6/RT/08). Dublin: Central Bank and Financial Services Authority of Ireland.

Melitz, M. (2003). The impact of trade on intraindustry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica, 71(6), 1695–1725.

Melitz, M., & Ottaviano, G. (2008). Market size, trade, and productivity. Review of Economic Studies, 75(1), 295–316.

Schmitt, N., & Yu, Z. (2001). Economics of scale and the volume of intra-industry trade. Economics Letters, 74(1), 127–132.

Yu, Z. (2002). Entrepreneurship and intra-industry trade. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv/Review of World Economics, 138(2), 277–290.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Ron Davies, Bruce Blonigen, Peter Lambert, and seminar participants at the 2008 Midwest International Economics meeting (Urbana-Champaign, IL) and NUI Maynooth for helpful discussions and comments. This draft has benefited a great deal from comments by two anonymous referees. All remaining errors are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Cole, M.T. Not all trade restrictions are created equally. Rev World Econ 147, 411–427 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-011-0090-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-011-0090-1