Abstract

This paper presents empirical evidence of the effect of FDI inflows on productivity convergence in Central and Eastern Europe, using a new and harmonized industry-level data set. Four conclusions stand out. First, there is a strong convergence effect in productivity, both at the country and at the industry level. Second, FDI inflow plays an important role in accounting for productivity growth. Third, the impact of FDI on productivity critically depends on the absorptive capacity of recipient countries and industries. Fourth, there is important heterogeneity across countries, industries and time with respect to some of the main findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

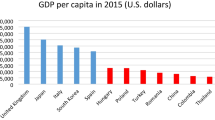

Weighted average of the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia. In this paper, Central and Eastern Europe refers to these eight EU countries.

For presentational reasons, the individual industries for which data are available have been lumped together in this section into four broadly defined sectors. Industry, in the first panel, mainly consists of manufacturing, together with mining and quarrying and electricity, water and gas supply (NACE categories D, C and E, respectively). The second sector is construction (NACE F). The third and fourth sectors are (market) services, with the former covering the more “traditional” services, such as trade and repairs, hotels and restaurants as well as transport and communication (NACE G, H and I), while the latter comprises financial and business-related services (NACE J and K). These four sectors together cover all economic activities except agriculture (and related branches) and non-market services.

In transition economies FDI inflows may also play an important role in the process of restructuring of formerly state-owned companies (see, e.g. Blanchard 1997).

See also Kokko (1994).

We use the xtabond2 procedure for Stata. See Roodman (2006).

We treat all lagged explanatory variables as predetermined, which means that they are assumed to be uncorrelated with present and future errors. This assumption might be violated, e.g. if FDI inflow is motivated by expectations of future shocks, which seems rather unlikely.

This means that our cross-section approach also exploits some time series variation in the data, although to a much lesser extent than the system GMM technique applied to yearly data.

EU KLEMS stands for EU analysis of capital (K), labour (L), energy (E), materials (M) and service (S) inputs. The database is downloadable at http://www.euklems.net. See also Koszerek et al. (2007) for its extensive overview.

These adjustments were done by the EU KLEMS consortium on the basis of agreed procedures to ensure harmonisation of the data and to generate growth accounts in a consistent and uniform way. Harmonisation focused, among others, on industrial classifications, aggregation levels, reference years for volume measures, price concepts and methods for solving breaks.

Bulgaria and Romania are not covered in the EU KLEMS database.

While data on mining and quarrying (NACE C), electricity, gas and water supply (NACE E) and manufacture of leather and leather products (DC) are generally available, these sections are excluded from our sample. The reason for doing so is their high regulation (C and E) or very small share in total economy’s output (DC). It has to be noted that adding these industries to our sample keeps the main results qualitatively unchanged.

Ideally, we would want to measure productivity as total factor productivity. Unfortunately, this and related measures are not available (or are hard to estimate in a consistent way) for the group of countries we focus on, particularly at this level of disaggregation.

Whenever possible, data on labour productivity and nominal value added are extrapolated to 2005 using official Eurostat sources.

Similarly to all value-added shares defined below, this ratio was calculated by converting the relevant variables to a common currency using market exchange rates.

This means that our measure of FDI inflow captures not only flow of funds, but also the revaluation effect. Unfortunately, the availability of direct data on FDI inflows is very limited, so relying on them would dramatically truncate our sample.

In the OLS estimation all yearly observations are pooled without imposing any cross-section structure. This implies that the first intercept is identical across all observations in the OLS specification.

In the OLS version there is only one intercept, common across all observations of a given 5-year subperiod.

This becomes apparent once one realises that our specification can be viewed as a special case of an error-correction model. By definition, \( \ln {\text{RLP}} = \ln {\text{LP}} - \ln {\text{LP}}^{*} \), where an asterisk indexes the euro area. By re-arranging the terms in Eq. 1 we obtain the long-run semi-elasticity of LP with respect to FDI equal to −γ/β.

Detailed results are available from the authors upon request.

This hypothesis seems to be confirmed by the unrestricted variant of our SUR estimations: if we allow the coefficients in regression 3 from Table 4 to vary across the two subperiods, we get a positive and significant estimate of the interaction term only in the first equation, covering the period 1995–2000 (see Table 7).

The estimation results described in this section are available from the authors upon request.

This is the approach pursued by Cameron et al. (2005) in a similar setup covering UK manufacturing industries.

References

Arellano, M., & Bond, S. R. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Review of Economic Studies, 58, 277–297.

Arellano, M., & Bover, O. (1995). Another look at the instrumental-variable estimation of error-components models. Journal of Econometrics, 68, 29–51.

Arratibel, O., Heinz, F. F., Martin, R., Przybyla, M., Rawdanowicz, L., Serafini, R., et al. (2007). Determinants of growth in the central and eastern European EU member states—A production function approach. (ECB occasional paper no. 61). European Central Bank, Frankfurt a.M.

Baas, T., Brücker, H., Hauptmann, A., & Jahn, E. J. (2009). The macroeconomic consequences of labour mobility. In Labour mobility within the EU in the context of enlargement and the functioning of the transitional arrangements. Available at http://www.wiiw.ac.at/.

Balasubramanyam, V. N., Salisu, M., & Dapsoford, D. (1999). Foreign direct investment as an engine of growth. Journal of International Trade and Economic Development, 8(1), 27–40.

Barrell, R., & Holland, D. (2000). Foreign direct investment and enterprise restructuring in Central Europe. Economics of Transition, 8(2), 477–504.

Barro, R. J. (1991). Economic growth in a cross section of countries. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106, 407–443.

Barro, R. J., & Sala-ì-Martin, X. (1997). Technological diffusion, convergence and growth. Journal of Economic Growth, 1, 1–26.

Basu, S., & Kimball, M. S. (1997). Cyclical productivity with unobserved input variation. (NBER working paper no. 5915). National Bureau of Economic Research, Washington, DC.

Benhabib, J., & Spiegel, M. M. (2005). Human capital and technology diffusion. In P. Aghion, & S. Durlauf (Eds.), Handbook of economic growth. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Blanchard, O. (1997). The economics of post-communist transition. Clarendon.

Blundell, R. W., & Bond, S. R. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87, 115–143.

Bond, S. R. (2002). Dynamic panel data models: A guide to micro data methods and practice. Portuguese Economic Journal, 1(2), 141–162.

Borensztein, E., De Gregorio, J., & Lee, J. (1998). How does foreign direct investment affect economic growth? Journal of International Economics, 45, 115–135.

Bound, J. D., Jaeger, D. A., & Baker, R. M. (1995). Problems with instrumental variables estimation when the correlation between the instruments and endogenous variables is weak. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 90, 443–450.

Cameron, G., Proudman, J., & Redding, S. (2005). Technological convergence, R&D, trade and productivity growth. European Economic Review, 49, 775–807.

Campos, N. F., & Coricelli, F. (2002). Growth in transition: What we know, what we don’t, and what we should. Journal of Economic Literature, 40(3), 793–836.

Carkovic, M., & Levine, R. (2005). Does foreign direct investment accelerate economic growth? In T. H. Moran, E. M. Graham, & M. Blomstrom (Eds.), Does foreign direct investment promote development? Peterson Institute for International Economics, Washington, DC.

Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1989). Innovation and learning: The two faces of R&D. Economic Journal, 99, 569–596.

Damijan, J. P., & Rojec, M. (2007). Foreign direct investment and the catching-up process in new EU member states: Is there a flying geese pattern? Applied Economics Quarterly, 53(2), 91–118.

Damijan, J. P., Knell, M., Majcen, B., & Rojec, M. (2003). The role of FDI, R&D accumulation and trade in transferring technology to transition countries: Evidence from firm panel data for eight transition countries. Economic Systems, 27(2), 189–204.

Djankov, S., & Hoekman, B. M. (2000). Foreign investment and productivity growth in Czech enterprises. World Bank Economic Review, 14(1), 49–64.

Doyle, P., Kuijs, L., & Jiang, G. (2001). Real convergence to EU income levels: Central Europe from 1990 to the Long Term. (IMF Working Paper No. 01/146). International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

Duczynski, P. (2003). Convergence in a model with technological diffusion and capital mobility. Economic Modelling, 20, 729–740.

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. (1994). Transition Report. London.

European Commission. (2004). The EU Economy: 2004 Review. Brussels.

Fillat Castejón, C., & Wörz, J. (2006). Good or bad? The influence of FDI on output growth: An industry-level analysis. (WIIW working paper no. 38). The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, Vienna.

Findlay, R. (1978). Relative backwardness, direct foreign investment, and the transfer of technology: A simple dynamic model. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 92, 1–16.

Gersl, A., Rubene, I., & Zumer, T. (2007). Foreign direct investment and productivity spillovers: Updated evidence from Central and Eastern Europe. (Working paper no. 8). Czech National Bank, Praha.

Glass, A., & Saggi, K. (1998). International technology transfer and the technology gap. Journal of Development Economics, 55(2), 369–398.

Görg, H., & Greenaway, D. (2004). Much ado about nothing? Do domestic firms really benefit from foreign direct investment? World Bank Research Observer, 19(2), 171–197.

Gorodnichenko, Y., Svejnar, J., & Terrell, K. (2007). When does FDI have positive spillovers? Evidence from 17 emerging market economies. (CEPR discussion paper no. 6546). Centre for Economic Policy Research, London.

Griffith, R., Redding, S., & Van Reenen, J. (2004). Mapping the two faces of R&D: Productivity growth in a panel of OECD industries. Review of Economics and Statistics, 86, 883–895.

Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1991). Innovation and growth in the global economy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Holland, D., & Pain, N. (1998). The diffusion of innovations in Central and Eastern Europe: A study of the determinants and impact of foreign direct investment. (NIESR discussion paper no. 137). National Institute of Economic and Social Research, London.

Hunya, G. (1997). Large privatisation, restructuring and foreign direct investment. In S. Zecchini (Ed.), Lessons from the transition: Central and Eastern Europe in the 1990s. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Hunya, G., & Schwarzhappel, M. (2007). WIIW database on foreign direct investment in Central, East and Southeast Europe: Shift to the East. FDI05/2007, WIIW.

Islam, N. (1995). Growth empirics: A panel data approach. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110, 1127–1170.

Kokko, A. (1994). Technology, market characteristics, and spillovers. Journal of Development Economics, 43, 279–293.

Kolasa, M. (2008). How does FDI inflow affect productivity of domestic firms? The role of horizontal and vertical spillovers, absorptive capacity and competition. Journal of International Trade and Economic Development, 17(1), 155–173.

Koszerek, D., Havik, K., Mc Morrow, K., Röger, W., & Schönborn, F. (2007). An overview of the EU KLEMS growth and productivity accounts. (Economic paper no. 290). European Commission, Brussels.

Lenain, P., & Rawdanowicz, L. (2004). Enhancing income convergence in Central Europe after EU accession. (OECD Economics Department working paper no. 392). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris.

Mankiw, N. G., Romer, D., & Weil, D. (1992). A Contribution to the Empirics of Economic Growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107, 407–437.

Mencinger, J. (2003). Does foreign direct investment always enhance economic growth? Kyklos, 56(4), 491–508.

Nelson, R. R., & Phelps, E. S. (1966). Investment in humans, technological diffusion, and economic growth. American Economic Review, 56, 69–75.

Nelson, C. R., & Startz, R. (1990). The distribution of the instrumental variables estimator and its t-ratio when the instrument is a poor one. Journal of Business, 63, 125–140.

Nickell, S. (1981). Biases in dynamic models with fixed effects. Econometrica, 49, 1417–1426.

Persyn, D. (2008). Trade as a wage disciplining device. (LICOS discussion paper no. 210). Catholic University, Leuven.

Polgar, E. K., & Wörz, J. (2009). Trade and wages: Winning and losing sectors in the enlarged European Union. Focus on European Economic Integration, Q1(09), 6–35.

Romer, P. M. (1990). Endogenous technological change. Journal of Political Economy, 98, 71–102.

Romer, P. (1993). Idea gaps and object gaps in economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 32(3), 543–573.

Roodman, D. (2006). How to do xtabond2: An introduction to “Difference” and “System” GMM in Stata. (Working paper no. 103), Center for Global Development, Washington.

Schadler, S., Ashoka, M., Abiad, A., & Leigh, D. (2006). Growth in the central and eastern European Countries of the European Union. (IMF occasional paper no. 252). International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

Timmer, M., O’Mahony, M., & van Ark, B. (2007). The EU KLEMS growth and productivity accounts: An overview. University of Groningen & University of Birmingham.

Wang, J.-Y. (1990). Growth, technology transfer, and the long-run theory of international capital movements. Journal of International Economics, 29, 255–271.

World Bank. (2008). Global economic prospects—Technology diffusion in the developing world. Washington, DC.

Acknowledgments

This paper was written while Marcin Kolasa was working in DG Economics of the ECB. The authors would like to thank the participants to the internal ECB seminar and the INFER Workshop in Cluj-Napoca for useful comments. Special thanks are owed to: Hans-Joachim Klöckers, Reiner Martin, Monica Pop-Silaghi and three anonymous referees.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Bijsterbosch, M., Kolasa, M. FDI and productivity convergence in Central and Eastern Europe: an industry-level investigation. Rev World Econ 145, 689–712 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-009-0036-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-009-0036-z