Abstract

We tested whether venous occlusion plethysmography (VOP) is an appropriate method to measure calf blood flow (CBF) during head-up tilt (HUT). CBF measured with VOP was compared with superficial femoral artery blood flow as measured by Doppler ultrasound during incremental tilt angles. Measurements of both methods correlated well (r = 0.86). Reproducibility of VOP was fair in supine position and 30° HUT (CV: 11%–15%). This indicates that VOP is an applicable tool to measure leg blood flow during HUT, especially up to 30° HUT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The main mechanism responsible for maintaining blood pressure during orthostatic stress is arteriolar vasoconstriction [6]. In order to quantify the response in vascular resistance to postural stress, in particular in the leg, it is necessary to measure leg blood flow accurately.

Venous occlusion plethysmography (VOP) is a well-established method to measure calf blood flow, which has been used in a variety of conditions, i.e. exercise [13] and reactive hyperaemia [17]. However, its use for measuring leg blood flow in standing or head-up tilt (HUT) position remains controversial, since an empty venous system has been suggested to be requisite for this method [3, 4, 12]. Since in the upright posture veins are already distended, due to an increase in hydrostatic pressure, further collection of blood may be defined by venous compliance rather than arterial inflow. This may question the validity of measuring blood flow using VOP in dependent limbs or in the upright posture. Although VOP has been used during HUT, accuracy or reproducibility of this method has not been reported [22–24].

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess the applicability and reproducibility of VOP for blood flow measurements in the calf (CBF) during HUT at different tilt angles (0°, 30°, 45°, and 70°). In a subgroup CBF measurements by VOP were compared with blood flow measurements using Doppler ultrasound. To assess reproducibility of VOP, measurements were performed twice.

Materials and methods

Subjects

In total eighteen healthy, normotensive subjects aged 21–30 years volunteered to participate in this study. In eight subjects blood flow measurements using VOP were compared with blood flow measurements using Doppler ultrasound (DU). In nine other subjects the VOP measurements were repeated within two weeks to assess reproducibility.

Baseline subject characteristics are illustrated in Table 1. None of the subjects used cardiovascular medication or suffered from cardiovascular disease. All were non-smokers and had no history of syncope. All volunteers refrained from caffeine and alcohol for at least eighteen hours and from food intake for three hours prior to testing. The local medical ethical committee approved the study. All subjects gave their written informed consent.

Measurements

The subjects lay in supine position on a manually driven tilt table and were supported by a saddle. The venous occlusion cuff was placed around the right thigh and connected to a rapid cuff inflator (Hokanson Stopler E-20, Bellevue, WA 98005, USA). The mercury-in-silastic strain gauge was placed around the thickest part of the calf and was connected to the plethysmograph. Red blood cell velocities and systolic and diastolic vessel diameter of the right superficial femoral artery were measured with a pulsed-colour Doppler device, which is described in detail elsewhere [8]. Reproducibility of DU in the superficial femoral artery was 1.5% for diameter, 14% for blood flow [9].

Protocol

Supine blood flow measurements using DU and VOP were performed after subjects were 30 minutes quietly in supine position. When the subject was 2 minutes into 30° HUT, DU measurements started until 3.5 minutes where after CBF continued for another 3.5 minutes. The venous occlusion pressure was adjusted to the hydrostatic pressure column, which is derived from the vertical distance heart level–thigh level and was calculated as the sinus of the tilt angle * actual distance heart–thigh, and was 75 mmHg during 30° HUT. The same procedure was repeated for 45°, and 70° HUT using a venous occlusion pressure of 87, and 105 mmHg, respectively.

Data analysis

CBF in ml·100 ml−1 · minute−1 was calculated as described previously [25] and values from minute 3.5 until 7 were averaged to calculate CBF for each HUT position. Doppler ultrasound measurements were analyzed as described before [8] to obtain superficial femoral artery blood flow. To compare CBF measurements with superficial femoral artery blood flow, CBF measurements in ml·100 ml−1 minutes−1 were multiplied by lower leg volume (ml) as measured by water displacement.

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

The results of each method were correlated and agreement evaluated according to the method described by Bland and Altman [5]. The limits of agreement are defined as the mean of the relative differences between the two methods ± 2 SD. Student’s t-test was used to test for systemic differences between the two methods.

Reproducibility of the CBF was assessed by calculating the coefficient of variance (CV) from two measurements [25].

To determine whether hemodynamic responses were dependent on the angle of tilt one-way repeated measures ANOVA’s were applied. If significant effects of tilt were observed post-hoc paired t-tests with Bonferroni correction for multiple testing were used. A P-value of <0.05 was considered to indicate significance.

Results

In five volunteers, CBF could not be measured during 70° head-up tilt (HUT), due to a poor plethysmography signal or near fainting of the subject.

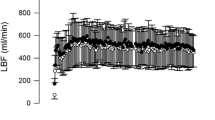

Hemodynamic responses to HUT (Figure 1)

CBF and superficial femoral artery blood flow (BF SFA) decreased significantly from supine to 30° with no further decrease with increasing tilt angle (Figure 1). The relative decrease in CBF (46% ± 11%) from supine to 30° was significantly larger than the decrease in BF SFA (40% ± 12%) (P < 0.001).

Absolute values of calf blood flow (CBF) measured with venous occlusion plethysmography and superficial femoral artery blood flow (BF SFA), heart rate (HR) and mean arterial pressure (MAP) during supine position, 30°, 45°, and 70° HUT. One-way repeated measures ANOVA showed a significant effect of tilt for all parameters. *P < 0.05 and indicates significantly different from the position before. ■ = supine;  = 30° HUT;

= 30° HUT;  = 45° HUT; □ = 70° HUT

= 45° HUT; □ = 70° HUT

Agreement VOP and DU

The Pearson correlation between the two methods was 0.86 (P < 0.001) for all data points (Figure 2). The agreement between the two methods was evaluated by plotting the relative difference in each measurement against the mean for all data points and separated for the different tilt angles (Figure 3). The relative mean difference ((VOP–DU)/DU) was −14% ± 22% for all data points in supine position and HUT indicating that overall CBF (VOP) is lower than BF SFA (DU); for supine position the relative mean difference between VOP and DU was 1.5% ± 24%; for 30°: −13% ± 23%; for 45°: −23% ± 19%; for 70°: −23% ± 15%. Limits of agreement for all data points in supine position and during HUT were −58% to 31% and became smaller during HUT. The limits of agreement are reasonable, although CBF during HUT is lower than BF SFA.

Reproducibility of VOP during head-up tilt

The coefficient of variation (CV) of CBF ranged between 8.7% and 15.0% (Table 2). In 70° HUT, the CV for both parameters was calculated over four subjects only.

Discussion

Calf blood flow (CBF) measured with VOP correlates well with superficial femoral artery blood flow (BF SFA) measured with DU, and can be measured reproducibly during HUT. Since the most profound changes in blood flow with both techniques were already measured in 30° HUT, and the increase in hydrostatic and venous pressure, and concomitant technical difficulties are smallest from supine to 30° HUT we recommend to use VOP for leg blood flow measurements during HUT up to 30°.

The decrease in leg blood flow assessed with VOP and DU, is comparable to tilt-induced blood flow changes in other studies using DU (33%–59%) [2, 7, 10, 11]. The strong relationship between VOP and DU blood flow measurements in the present study is in line with previous studies reporting correlation coefficients varying from 0.57 to 0.99 at rest and during exercise [14, 16, 27]. Head-up tilt affects muscle blood flow more than skin blood flow [21, 28]. Since skin blood flow contributes more to superficial femoral blood flow than to calf blood flow, this may explain the observed discrepancy between the decrease in CBF (∼48%) versus the decrease in superficial femoral artery blood flow (∼40%) in response to HUT.

Reproducibility of baseline CBF (15.0%) is in range with other studies using similar techniques to measure leg blood flow [1, 18, 25]. The coefficient of variation of CBF during HUT was even better (11.0%–17.9%), which indicates that VOP is a reproducible tool to measure tilt-induced vasoconstriction repetitively. The low coefficients of variation of CBF during 70° (8.7%–8.9%) are not representative since these coefficients of variation were calculated over no more than 4 subjects. Not all subjects were able to abstain from moving their legs in 70° HUT position, and some subjects fainted in this position. Moreover, the quality of the plethysmographic tracing became worse at 70° HUT whereas at the lower tilt angles the plethysmography signal is of good quality indicated by the volume pulsations in the plethysmographic tracing for the period of venous occlusion.

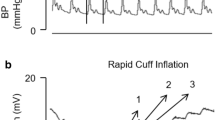

Our data and previous studies [15, 19, 20, 26] show that at 30° HUT peripheral vascular responses are accomplished to a large extent. The increase in hydrostatic pressure and concomitant increase in venous pressure is low at 30°. From Figure 4B it can be concluded that at 30° HUT venous compliance is still at the steep portion of the venous compliance curve whereas during 45°, and 70° HUT the venous compliance has shifted to the non-linear part. At 30° HUT increase of the plethysmography signal during venous occlusion is linear while at 45° and 70° HUT, venous distensibility is reduced and consequently results in a non-linear increase in leg volume during inflation of the venous occlusion cuffs, which is illustrated in Figure 5. We therefore recommend using VOP at 30° HUT. For studies focussing on syncope at the endpoint of HUT, which requires larger tilt angles, other techniques to measure leg blood flow should be used.

(A) Pressure-Volume curve and (B) Pressure Compliance curve based on data of a similar group of volunteers measured by venous occlusion plethysmography at different cuff occlusion pressures (for method and protocol see de Groot et al., Journal of applied Physiology, 2005). The increases in calf volume in response to 30°, 45°, and 70° HUT are marked by the dotted lines in the pressure volume curve (A). The different tilting angles correspond with different venous pressures (x-axis). Transferring these venous pressures into the pressure-compliance curve (B) clearly demonstrate that during 30° HUT venous compliance is still on the steep linear part of the curve, whereas during 45°, and 70° HUT the venous compliance is compromised

Typical plethysmographic tracing of one individual subject during a complete experiment. Blood flow measurements at 30° HUT start when the plethysmography signal does not change anymore, meaning that venous volume reached a steady state situation. Besides, looking at a typical VOP tracing at 30° HUT, the increase in venous volume is linear during the first 5 seconds of cuff inflation, indicating that blood flow measurements using VOP during 30° HUT are not compromised by a decrease in venous compliance

Limitation

Using VOP, blood flow is defined as limb volume changes over time. During HUT, when the leg is below heart level, volume changes can still be measured using VOP, however, the physiological determinants of these volume changes are complex and it is no longer possible to say with reasonable certainty that a change in volume over time, which most likely reflects flow, is determined by resistance vessel tone. For example, limb blood flow measured using VOP in HUT position can decrease due to an increase in venous pressure, as a result of venous congestion and the associated fall in arterio-venous pressure gradient, without any increase in resistance at the arteriolar level.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that CBF measured by VOP during HUT is suitable and reproducible. The method is easy applicable and recommended in tilt angles equal to 30° to avoid high hydrostatic and leg venous pressures.

References

Altenkirch HU, Koch G, Koralewski HE (1990) Variability and reproducibility of arterial and venous circulation parameters in the forearm and calf measured at one-week intervals. Vasa 19:21–25

Arbeille P, Herault S (1998) Cardiovascular echographic and Doppler parameters for the assessment of orthostatic intolerance. Eur J Ultrasound 7:53–71

Barendsen GJ (1980) Plethysmography. In: Verstraeten M (ed) Methods in angiology. Martin Nijhoff Publishers, The Hague, p 51–88

Barendsen GJ, Venema H, van den Berg J (1971) Semicontinuous blood flow measurement by triggered venous occlusion plethysmography. J Appl Physiol 31:288–291

Bland JM, Altman DG (1986) Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1:307–310

Brown CM, Hainsworth R (2000) Forearm vascular responses during orthostatic stress in control subjects and patients with posturally related syncope. Clin Auton Res 10:57–61

Castellano V, Olive JL, Stoner L, Black C, McCully KK (2004) Blood flow response to a postural challenge in older men and women. Dyn Med 3:1

De Groot PC, Van Kuppevelt DH, Pons C, Snoek G, Van Der Woude LH, Hopman MT (2003) Time course of arterial vascular adaptations to inactivity and paralyses in humans. Med Sci Sports Exerc 35:1977–1985

de Groot PCE, Poelkens F, Kooijman M, Hopman MTE (2004) Preserved flow-mediated dilation in the inactive legs of spinal cord-injured individuals. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287:H374–H380

Groothuis JT, Boot CR, Houtman S, van Langen H, Hopman MT (2005) Does peripheral nerve degeneration affect circulatory responses to head-up tilt in spinal cord-injured individuals? Clin Auton Res 15:99–106

Imadojemu VA, Lott ME, Gleeson K, Hogeman CS, Ray CA, Sinoway LI (2001) Contribution of perfusion pressure to vascular resistance response during head-up tilt. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 281:H371–H375

Joyner MJ, Dietz NM, Shepherd JT (2001) From Belfast to Mayo and beyond: the use and future of plethysmography to study blood flow in human limbs. J Appl Physiol 91:2431–2441

Joyner MJ, Lennon RL, Wedel DJ, Rose SH, Shepherd JT (1990) Blood flow to contracting human muscles: influence of increased sympathetic activity. J Appl Physiol 68:1453–1457

Levy BI, Valladares WR, Ghaem A, Martineaud JP (1979) Comparison of plethysmographic methods with pulsed Doppler blood flowmetry. Am J Physiol 236:H899–H903

Matalon SV, Farhi LE (1979) Cardiopulmonary readjustments in passive tilt. J Appl Physiol 47:503–507

Pallares LC, Deane CR, Baudouin SV, Evans TW (1994) Strain gauge plethysmography and Doppler ultrasound in the measurement of limb blood flow. Eur J Clin Invest 24:279–286

Patterson GC, Whelan RF (1955) Reactive hyperaemia in the human forearm. Clin Sci 14:197–211

Roberts DH, Tsao Y, Breckenridge AM (1986) The reproducibility of limb blood flow measurements in human volunteers at rest and after exercise by using mercury-in-Silastic strain gauge plethysmography under standardized conditions. Clin Sci (Colch) 70:635–638

Saito M, Foldager N, Mano T, Iwase S, Sugiyama Y, Oshima M (1997) Sympathetic control of hemodynamics during moderate head-up tilt in human subjects. Environ Med 41:151–155

Sander-Jensen K, Secher NH, Astrup A, Christensen NJ, Giese J, Schwartz TW, Warberg J, Bie P (1986) Hypotension induced by passive head-up tilt: endocrine and circulatory mechanisms. Am J Physiol 251:R742–R748

Scremin G, Kenney WL (2004) Aging and the skin blood flow response to the unloading of baroreceptors during heat and cold stress. J Appl Physiol 96:1019–1025

Stewart JM (2003) Microvascular filtration is increased in postural tachycardia syndrome. Circulation 107:2816–2822

Stewart JM (2002) Pooling in chronic orthostatic intolerance: arterial vasoconstrictive but not venous compliance defects. Circulation 105:2274–2281

Stewart JM, Weldon A (2003) Contrasting neurovascular findings in chronic orthostatic intolerance and neurocardiogenic syncope. Clin Sci (Lond) 104:329–340

Thijssen DH, Bleeker MW, Smits P, Hopman MT (2005) Reproducibility of blood flow and post-occlusive reactive hyperaemia as measured by venous occlusion plethysmography. Clin Sci (Lond) 108:151–157

Toska K, Walloe L (2002) Dynamic time course of hemodynamic responses after passive head-up tilt and tilt back to supine position. J Appl Physiol 92:1671–1676

Tschakovsky ME, Shoemaker JK, Hughson RL (1995) Beat-by-beat forearm blood flow with Doppler ultrasound and strain-gauge plethysmography. J Appl Physiol 79:713–719

Vissing SF, Scherrer U, Victor RG (1994) Increase of sympathetic discharge to skeletal muscle but not to skin during mild lower body negative pressure in humans. J Physiol 481(Pt 1):233–241

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the participation of all subjects in this study. In addition, we would like to thank Bregina Kersten and Jos Evers for assistance during the experiments. There are no disclosures to mention.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kooijman, M., Poelkens, F., Rongen, G.A. et al. Leg blood flow measurements using venous occlusion plethysmography during head-up tilt. Clin Auton Res 17, 106–111 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10286-007-0402-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10286-007-0402-7