Abstract

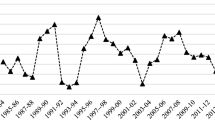

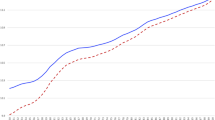

This paper presents capital services estimates for 26 Portuguese industries for the 1977–2003 period. The estimation procedure follows an integrated approach under which the flows of capital services are approximated as a proportion of the capital stock converted into standard efficiency units. Our findings suggest a close proximity between the evolution of capital flows and the observed fluctuations of Portuguese macroeconomic growth. TFP growth estimates based on growth accounting reveal, furthermore, a very disappointing performance of the Portuguese economy during the period under study, with an average annual rate of TFP growth of 0.8% being observed. Performance varies across industries, but the bulk of activities show very modest rates of TFP growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The latest release of the EU KLEMS database (http://www.euklems.net) has recently provided capital services estimates for the Portuguese case for the 1996–2005 period. A comparison of these estimates with those developed in the present paper is provided in Section 6.

\(F_\tau ^i \) gives the cumulative value of the retirement distribution, describing the probability of survival over the capital vintage’s life span.

By weighting the stocks of different assets by their relative productivity in production, the overall productive stock will then constitute a measure of the potential flow of productive services that all fixed assets can deliver in production.

pit is the market price of a new asset.

The use of this index is based on its approximation to general functional forms of the production function (see in this respect, OECD 2001b).

Data on investment per sector are not published, but can be obtained from INE under request.

In this respect we follow the OECD (2001a) recommendations, which acknowledge that in general terms land should not be treated as gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) in the measurement of productivity (see OECD 2001a: 76). Furthermore, in our case, this asset constitutes only a negligible part of the GFCF, never exceeding 2% of its total value during the whole period under study.

Given our purpose of analysis—the measurement of TFP growth—the only relevant part of residential investment is the investment carried out by specialised producers of market services (OECD 2001a).

This information is available on-line at http://www.bportugal.pt.

The total GFCF series for the 26 industrial branches, both in nominal and real terms, can be obtained from the author upon request.

The geometric pattern assumes a constant rate of decline in the efficiency of an asset as it ages.

It is worth mentioning that there is relatively little scientific basis for defining β values. ABS follows BLS practices, which, in turn, sets their values in order to yield age-price profiles similar to the ones implicit in BEA’s (Bureau of Economic Analysis) estimates on wealth.

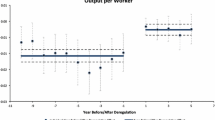

We realise that considering service lives from other countries does not capture the specificities of the Portuguese case. In Section 5.3 we analyse the effect of potential errors in the average service lives considered by running the perpetual inventory method with alternative estimates of service lives.

See, for example, the estimates presented by the US, Canada and the Czech Republic included in the OECD (2001b), and the estimates used by ABS, available on line at http://abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS.

Portuguese national accounts include hardware equipment in the “machinery and equipment” category, whereas software equipment is included in “other investment”. Investment in infrastructure is included in the “buildings” category.

For example, we assumed the mean asset lives of the rubber and plastics industry to be similar to the ones regarding the chemicals industry.

Given the volatility of investment figures we use the average value of investment between 1977 and 1979, rather than the value of investment observed at the beginning of the period under analysis, as in Kamps (2006).

Differences in tax treatment between asset types have not been considered due to lack of data.

ξi is the expected rate of change of nominal user costs.

See OECD (2001a, pp. 69–71) for a more detailed description of the method.

The computation of capital services for the economy as a whole was made taking the total GFCF values by asset type and using the methodology and assumptions outlined in the text. Average service lives of the assets at the broad macroeconomic level were computed as a weighted average of industry asset lives, taking the relative importance of each sector in total productive capital stock (by asset) as weights.

Age-efficiency and age-price profiles coincide, which leads in turn to the coincidence of net and productive capital stocks at the level of individual assets. Furthermore, the depreciation rate used in the computation of user costs equals that used in the measurement of the productive capital stocks.

No explicit retirement function is formulated, since the geometric model is typically seen as capturing both the effects of wear and tear and retirement.

From 1987 onwards, both series show the same average growth rate, around 3.7%.

Due to space limitations, the results of the sensitivity analysis at the sectoral level are not presented. These results can be obtained from the author upon request.

More precisely, the industrial censuses took place in 1958, 1964 and 1972.

Coverage varied over time, but the last census took only into account firms of this type.

In particular, the results for manufacturing were provided as a whole, and only two assets (buildings and equipment) were considered.

This information is available on-line at http://www.bportugal.pt.

Initial capital stocks for the beginning of 1953 were also estimated using the Kamps’ methodology, but as indicated earlier, those stocks cease to influence the capital input flow in the period under analysis (1977–2003), in the case of machinery, transport and other investment assets.

At the industry level, the computation of capital services using a geometric profile-based procedure for generating the initial stocks (cf. de la Fuente and Domenéch 2002; Kamps 2006) has also been performed. The consideration of the alternative initial stocks does not affect significantly the capital services series from the mid-1980s onwards for most of the industrial branches considered. Although there are a few branches in which the differences across the two sets of estimates persist for most of the period under analysis (e.g., textiles and clothing, construction, financial intermediation and business activities), in most cases the initial discrepancies are significantly reduced after the first 8/9 years. These results can be obtained from the author upon request.

Due to space limitations, these results are not shown, but can be obtained from the author upon request.

The very small number of firms in chemicals and petroleum products industries in the Portuguese case can also explain the more erratic GFCF series and, to some extent, the higher vulnerability of these industries to eventual statistical errors.

This database, which is available on-line at http://www.ggdc.net, provides data on current value added, value added deflators and hours worked for 56 industries in the 1979–2003 period for several countries, including Portugal.

This is the same source used by GGDC in the compilation of Portuguese output and output deflators data.

During the 1977–1979 period there were no changes in the number of established working days and in the total number of hours worked per day (Leite and Almeida 2001). It seems reasonable therefore to expect that the variation of the total number of hours worked should follow closely the employment variation rates in each sector.

The labour compensation includes only the compensation of employees, although to be precise, a part of the income generated by self-employed persons should also be included. The conventional approach to deal with the “mixed income” component (OECD 2001a, p. 45) could not be used in the present case because there was no information regarding the number of the self-employed for many years of the sample.

These computations are based on the capital input series derived using the hyperbolic age-efficiency profile and taking into account the 1953–2003 database (cf. Section 5.2).

In ideal terms, the measure of labour input should be adjusted for the effects of changing labour composition. Unfortunately, there is no information regarding changes in labour quality for the Portuguese case at the sectoral level for the whole period under study (the only available sources are the General Population Censuses, which are conducted every 10 years, and Quadros de Pessoal, which have information only from the end of the 1980s onwards). We believe, however, that our estimates would not be significantly affected by the additional consideration of changes in the composition of the labour force. According to the evidence found in studies investigating human capital trends in Portugal in the last few decades, the rate of increase in this factor has been relatively low (cf. Teixeira and Fortuna 2004, 2010). Furthermore, according to the last Population Census, from 2001, the large majority of the Portuguese workforce still has a very low level of schooling, which is apparent from the huge percentage of individuals who do not possess more than 6 years of formal education (about half of the total labour force), and from the small percentage of those who have a university diploma (only 12%).

Several studies report this pro-cyclical feature (e.g., Timmer 1999; OECD 2001a), which seems to be partially related with measurement problems. Although statistical data capture output volume changes relatively well, the same does not occur with regard to changes in the rate of utilisation of inputs. As a consequence, output changes tend to be followed by generally more stable input measures, which lead to the observed pro-cyclical nature of productivity growth estimates.

According to the methodology document which accompanies the database, also available on-line at http://www.euklems.net, additional sources to national accounts have been used to distinguish between labour types and investment series for the eight capital assets. The sources document, however, does not indicate those sources with respect to the Portuguese case. Furthermore, information on the main sources of GFCF series at the industry level, and on the definition of initial capital stocks is also not available, which makes more difficult the comparison between both sets of estimates.

Information on TFP growth is provided between years that mark the same position in the business cycle, in order to facilitate interpretation (OECD 2001a).

Cf. Table 3.

It is worth noting, however, that the non-adjustment of labour input to quality changes has probably underestimated the contribution from labour to production.

Growth in capital accounts also for most part of the increase in value added in the majority of the industries under study. Detailed information on the contributions of the different sources of growth at the sectoral level can be obtained from the author upon request.

It is worth mentioning, furthermore, that because the computation of TFP in the Portuguese case does not take into account the labour composition effect, TFP growth estimates are probably over-valued.

Cf. Mas et al. (2008), for an analysis of the causes behind the recent (poor) productivity performance of the Spanish economy.

The relative backwardness of both countries made them eligible for the Structural Funds and the Cohesion Fund, which materialised into a strong upturn in infrastructure investment.

Labour productivity accelerated in both countries from 1980–1995 to 1995–2005. In Greece, labour productivity increased from 0.2 to 1.8%, whereas in Ireland it increased from 2.3 to 3.2% (own computations based on EU-KLEMS Database, March 2008).

References

Afonso O (1999) Contributo do comércio externo para o crescimento económico português, 1960–93. Conselho Económico e Social, Lisbon

Amador J, Coimbra C (2007) Characteristics of the Portuguese economic growth: what has been missing? Banco de Portugal Working Paper, 8/2007

Baldwin JR, Gu W (2007) Multifactor productivity in Canada: an evaluation of alternative methods of estimating capital services. The Canadian Productivity Review, April, Statistics Canada, Economic Analysis Division

Biatour B, Byron G, Kegels C (2007) Capital services and total factor productivity measurements: impact of various methodologies for Belgium. Working Paper 2-07, Federal Planning Bureau of Belgium

Blanchard O (2007) Adjustment within the Euro. The difficult case of Portugal. Portuguese Economic Journal 6(1):1–21

de la Fuente A, Doménech R (2002) Human capital in growth regressions: how much difference does data quality make? An update and further results, CEPR Discussion Paper no. 3587

Diewert WE (2001) Measuring the price and quantity of capital services under alternative assumptions. Discussion Paper No 01-24, Department of Economics, University of British Columbia

Erumban AA (2008) Rental prices, rates of return, capital aggregation and productivity: evidence from EU and US. CESifo Econ Stud 54(3/2008):499–533

Griliches Z (1990) Hedonic price indexes and the measurement of capital and productivity: some historical reflections. In: Berndt ER, Triplett JE (eds) Fifty years of economic measurement. Studies in Income and Wealth 54, National Bureau of Economic Research

Harper DJ, Berndt ER, Wood DO (1989) Rates of return and capital aggregation using alternative rental prices. In: Jorgenson DW, Landau R (eds) Technology and capital formation. MIT, Cambridge

Hulten CR, Wykoff FC (1996) Issues in the measurement of economic depreciation: introductory remarks. Econ Inq 34:10–23

Inklaar R, Timmer MP, van Ark B (2008) Market services productivity across Europe and the US. Econ Policy 23(53):139–194

Jorgenson D (1995) Productivity volume 1: postwar US economic growth. MIT, Cambridge

Jorgenson DW, Gollop FM, Fraumeni BM (1987) Productivity and US economic growth. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Kamps C (2006) New estimates of government net capital stocks for 22 OECD countries 1960–2001. IMF Staff Pap 53(1):120–150

Lains P (2003) Catching up to the European core: Portuguese economic growth, 1910–1990. Explor Econom Hist 40:369–386

Leite J, Almeida FJ (2001) Legislação do Trabalho. Revista e Actualizada. Coimbra Editora, Coimbra

Lopes JS (1996) A Economia Portuguesa desde 1960, Gradiva

Losch M (2006) Deepening the Lisbon. Agenda: studies on productivity, services and technologies. Austrian Federal Ministry of Economics and Labour, Vienna

Mas M, Milana C, Serrano L (2008) Spain and Italy: catching up and falling behind. Two different tales of productivity slowdown. Working Paper No 37, EU KLEMS

Meinen G (1998) Lives of capital goods. Statistics Netherlands, The Hague

Meinen G, Verbiest P, de Wolf P (1998) Service lives, discard patterns and depreciation methods. Statistics Netherlands, The Hague

Neves JC (1994) The Portuguese economy: a picture in figures. XIX and XX centuries. Universidade Católica Editora, Lisboa

OECD (2001a) Measuring productivity—OECD manual: measurement of aggregate and industry-level productivity growth. OECD, Paris

OECD (2001b) Measuring capital—OECD manual: measurement of capital stocks, consumption of fixed capital and capital services. OECD, Paris

OECD (2009) Measuring capital—OECD manual. OECD, Paris

Osada H (1994) Trade liberalization and FDI Incentives in Indonesia: the impact on industrial productivity. Dev Econ XXXII-4:479–491

Oulton N (2007) Expost versus ex ante measures of the user cost of capital. Rev Income Wealth 53(2):295–317

Oulton N, Srinivasan S (2003) Capital stocks, capital services, and depreciation: an integrated framework. Working Paper No 192, Bank of England

Pina A, St Aubyn M (2004) Comparing macroeconomic returns on human and public capital: an empirical analysis of the Portuguese case (1960–2001). Working Paper, ISEG

Santos E (1984) O stock de capital na economia Portuguesa—1953–1981. Documento de trabalho No 6, Banco de Portugal, Estudos e Documentos de Trabalho

Schreyer P (2003) Capital stocks, capital services and multi-factor productivity measures. OECD Econ Stud 37(2):163–184

Schreyer P, Bignon P, Dupont J (2003) OECD capital services estimates: methodology and a first set of results. OECD Statistics Working Paper

Teixeira A, Fortuna N (2004) Human capital, innovation capability and economic growth in Portugal, 1960–2001. Portuguese Economic Journal 3(3):205–225

Teixeira A, Fortuna N (2010) Human capital, trade and long-run productivity. Testing the technological absorption hypothesis for the Portuguese economy, 1960–2001. Res Policy (in press)

Timmer M (1999) Indonesia’s ascent on the technology ladder: capital stock and total factor productivity in Indonesian manufacturing, 1975–95. Bull Indones Econ Stud 35(1):75–97

van Ark B, O’Mahony M, Timmer M (2008) The productivity gap between Europe and the US: trends and causes. J Econ Perspect 22(1):25–44

Acknowledgement

The author is deeply indebt for the helpful comments and suggestions of two anonymous referees. The usual caveat applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

About this article

Cite this article

Gomes da Silva, E. Capital services estimates in Portuguese industries, 1977–2003. Port Econ J 9, 35–74 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10258-010-0053-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10258-010-0053-9