Abstract

This study investigates the longitudinal variation of lateral entrapment of suspended sediment, as is observed in some tidal estuaries. In particular, field data from the Yangtze Estuary are analysed, which reveal that in one cross-section, two maxima of suspended sediment concentration (SSC) occur close to the south and north sides, while in a cross-section 2 km down-estuary, only one SSC maximum on the south side is present. This pattern is found during both spring tide and neap tide, which are characterised by different intensities of turbulence. To understand longitudinal variation in lateral trapping of sediment, results of a new three-dimensional exploratory model are analysed. The hydrodynamic part contains residual flow due to fresh water input, density gradients and Coriolis force and due to channel curvature-induced leakage. Moreover, the model includes a spatially varying eddy viscosity that accounts for variation of intensity of turbulence over the spring-neap cycle. By imposing morphodynamic equilibrium, the two-dimensional distribution of sediment in the domain is obtained analytically by a novel procedure. Results reveal that the occurrence of the SSC maxima near the south side of both cross-sections is due to sediment entrapment by lateral density gradients, while the second SSC maximum near the north side of the first cross-section is by sediment transport due to curvature-induced leakage. Coriolis deflection of longitudinal flow also contributes the trapping of sediment near the north side. This mechanism is important in the upper estuary, where the flow due to lateral density gradients is weak.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In many estuaries, one or more locations are present where the tidally mean suspended sediment concentration (SSC) attains a maximum. Understanding the mechanisms resulting in these so-called estuarine turbidity maxima (ETMs) is important, as mouth bar is frequently formed in ETMs and hampers marine traffic (Liu et al. 2011) and it has a significant impact on the ecological functioning of estuaries (Cloern et al. 2013), e.g. it causes deficits in oxygen (Talke et al. 2009a; Zhu et al. 2011). The latter is due to the fact that SSC contains organic material that consumes oxygen. Moreover, high sediment concentrations strongly limit the light that is needed for phytoplankton to grow (May et al. 2003; Jiang et al. 2015).

The locations of turbidity maxima depend on estuarine settings and forcing conditions. Many studies have focused on the mechanisms underlying the distribution of turbidity related to either longitudinal or lateral sediment transport. An important process that results in longitudinal sediment trapping is the joint action of seaward transport caused by river flow and the landward transport by the density-driven flow (Postma 1967; Festa and Hansen 1978; Schubel and Carter 1984; Geyer 1993; Talke et al. 2009b). In that case, the maximum SSC occurs at the landward limit of the salt intrusion. Furthermore, the suppression of turbulence by stratification of the water column significantly enhances trapping of sediment at the landward end of the salinity intrusion (Geyer 1993). Jay and Musiak (1994) and Sanford et al. (2001) demonstrated that net sediment transport due to ebb-flood asymmetry in intensity of turbulence during a tidal cycle significantly affects the location of the turbidity maximum. A similar conclusion was made by Chernetsky et al. (2010) with respect to net sediment transport that results from the interaction between the M2 tide and external M4 tide. Recent studies (Donker and de Swart 2013; Winterwerp et al. 2013) stressed the role of flocculation and hindered settling in sediment trapping.

Other studies focused on lateral trapping of suspended sediment at a fixed cross-section (Huijts et al. 2006; Kim and Voulgaris 2008; Chen and Sanford 2009; Yang et al. 2014). Interestingly, little attention has been devoted to quantifying and understanding how the joint presence of longitudinal and lateral processes in an estuary results in a three-dimensional structure of the turbidity field.

Field data reveal that lateral distribution of suspended sediment concentration shows longitudinal differences. In the Hudson River Estuary, Geyer et al. (2001) observed that, in a cross-section in the upper reach, turbidity maxima occurred on both left and right sides, whereas in a cross-section near the mouth, only one turbidity maximum was only found on the left side (when looking into the estuary). Recent data collected in the North Passage of the Yangtze Estuary, China, also show different turbidity maxima at two separate cross-sections. Moreover, the magnitudes of observed SSC during spring and neap tides are markedly different, whereas the lateral distribution is similar (data are presented in Section 2). These observations motivate the overall objective of the present study, i.e. to identify possible mechanisms that cause the lateral trapping of suspended sediment at different longitudinal locations and at different stages of the spring-neap cycle.

To gain thorough understanding of sediment entrapment mechanisms in tidal estuaries, both numerical and analytical models are important tools. The former allow for detailed simulation of flow and SSC distribution under controlled conditions (Burchard et al. 2004; Song and Wang 2013; van Maren et al. 2016) while the latter have been frequently used to obtain fundamental knowledge of physical processes (Huijts et al. 2006; Talke et al. 2009b; Schuttelaars et al. 2013; Yang et al. 2014). The aim of this work is to gain fundamental understanding about longitudinal variations in lateral sediment trapping in an estuary, rather than to reproduce all details of sediment transport in a specific estuary. Huijts et al. (2006) showed that at a fixed longitudinal location, the locations of sediment accumulation in a cross-section depend on the relative importance of lateral flow components induced by Coriolis deflection of longitudinal flow and by lateral density gradients. Inspired by their work, the first hypothesis of the present study is that the intensities of lateral flow components vary in the longitudinal direction, thereby resulting in different trapping locations of SSC. The second hypothesis is that the relative importance of each lateral flow component to the trapping of sediment is not sensitive to the varying intensity of turbulence from spring tide to neap tide.

To test these two hypotheses, a new three-dimensional exploratory model is employed. It extends the model of Huijts et al. (2006) in that conditions in the longitudinal direction are not uniform. The present model also extends an earlier model of Festa and Hansen (1978) in the sense that it includes both longitudinal and lateral dynamics. Besides, more sophisticated formulations for turbulent eddy viscosity and eddy diffusivity are used that depend on the degree of stratification and which allow for studying conditions during both spring and neap tides.

The details of the new field data (of the Yangtze Estuary), model and methods are presented in Section 2. In Section 3, the model results are presented and used to verify the two hypotheses. This is followed by a discussion in Section 4, and by the conclusions in Section 5.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Data

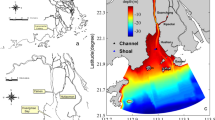

Two cross-sections in the North Passage of the Yangtze Estuary were sampled during spring and neap tides in February, 2013 (Fig. 1) by the Estuarine and Coastal Science Research Center, Shanghai (ECSRC). The first cross-section is labelled A and, it is 38 km downstream from the reference point (see Fig. 1b). The second cross-section (labelled B) is 2 km downstream from A. Velocities, water depth, salinity and SSC data were collected synchronously by instruments on board of two vessels that continuously moved back and forth at two cross-estuary transects during two full tidal cycles (25 h). The south and north sides of the two sampled transects are located on the regulation lines (see Fig. 1), which connect the most offshore ends of the groins that are present on either side of the channel banks, i.e. the training walls. Vessels completed 3-km transects in 30–45 min. Velocities and depths were measured with 600-kHz broadband acoustic Doppler current profilers. Optical backscatter sensors were used to measure SSC from water surface to the bottom at seven fixed locations that were evenly distributed over the two transects. The data were processed by ECSRC and were interpolated at hourly intervals and at six σ-levels, following the method of Shi (2004), i.e. at relative depths of 0 (surface), − 0.2,− 0.4,− 0.6,− 0.8, and − 1 (actually 0.5 m above the bottom). The data were subsequently decomposed into tidally averaged components and components related to tides with specific frequencies (M2, M4, O1, K1, ...) by applying harmonic analysis. The freshwater discharge of the Yangtze River during the observation period (from neap to spring tides) was 16,000–17,000 m3 s− 1, of which roughly 20–25% entered the North Passage. During neap tide, the measured tidal range was about 2.1 m and maximum instant tidal current speed was 1.7 m s− 1, while during spring tide, they were 3.5 m and 3.0 m s− 1, respectively.

a Map of the study area in the central and lower part of the Yangtze Estuary. b Zoom-out map of the study area including the location of the cross-sections at which measurements are available. The two cross-sections are located 38 and 40 km downstream from the reference point (yellow triangle). The regulation lines, which connect the offshore ends of the groins along the banks, are denoted by red solid lines. c A typical cross-estuary depth profile (cross-section A)

Time-averaged SSC collected at the two cross-sections A and B is shown in Fig. 2 (orientations are into the estuary). Note here that the vertical distance z† = σh(y) is the time-mean vertical position of a certain σ −surface, with h(y) representing the undisturbed depth. During spring tide, SSC at cross-section A attains maxima near both the south and north sides (Fig. 2a). At cross-section B (Fig. 2b) however, a turbidity maximum is found only near the south side. During neap tide (Fig. 2c, d), values of SSC in both two cross-sections are an order of magnitude lower than those during spring tide. Nevertheless, the basic lateral sediment distribution pattern remains unchanged, i.e. turbidity maxima occur on both the south and north sides at cross-section A and only one maximum is found (on the south shoal) at cross-section B.

Distribution of residual SSC (in kg m− 3) in cross-section A during spring tide (a), cross-section B during spring tide (b), cross-section A during neap tide (c) and cross-section B during neap tide (d). Locations are indicated in Fig. 1; z† is distance to the mean water surface. Orientation of all plots is into the estuary

As the stability of the water column and residual currents affect the distribution of SSC, data for salinity and residual currents are presented. Tidally averaged salinity at the two cross-sections exhibits variation in the vertical direction, with values in the deep channel ranging from 9 psu (Fig. 3a, b) and 4 psu (Fig. 3c, d) near the water surface, to 20 psu (Fig. 3a, b) and 22 psu (Fig. 3c, d) near the bottom during spring tide and neap tide, respectively. The water column is moderately stratified during spring tide, with bottom-to-surface salinity difference (Δs) of 6.3 and 6.6 psu at A and B, respectively (Fig. 3a, b). During spring tide, saltier water occurs near the north side and fresher water near the south side. During neap tide, the observed Δs are 14.5 psu at A and 16.5 psu at B (Fig. 3c, d).

The bulk Richardson number (Dyer 1997)

yields a quantitative measure of the ratio of stratification and destratification mechanisms at the two cross-sections. Here, g = 9.8 m s− 2 is gravitational acceleration, ρr = 1000 kg m− 3 is a constant reference density and Δρm = βΔs is the laterally averaged residual density difference between bottom and surface. It is assumed that water density only depends on salinity and β = 0.78 kg m− 3 psu− 1 is the salinity contraction coefficient. Furthermore, H is the laterally averaged water depth and Um is the laterally averaged tidal current amplitude. Harmonic analysis shows that the M2 tide is the dominant constituent, with Um = 1.6 m s− 1 during spring tide and Um = 0.8 m s− 1 during neap tide. Substitution of the measured values into Eq. 1 yields for both cross-sections that Ri ≃ 0.3 during spring tide and Ri ≃ 2.0 during neap tide. These numbers indicate that the water column is weakly stratified during spring tide and strongly stratified during neap tide.

The spatial patterns of the measured longitudinal residual flow in the two cross-sections are presented in Fig. 4. During spring tide, outflow occurs in most of the two cross-sections, with a maximum of 0.8 m s− 1 near the surface (Fig. 4a, b). In contrast, a clear two-layer flow structure is observed during neap tide, with an outflow of 0.4 m s− 1 near the surface and inward flow of 0.2 m s− 1 near the bottom of the channel (Fig. 4c, d).

Distribution of longitudinal residual flow (in cm s− 1) in cross-section A during spring tide (a), cross-section B during spring tide (b), cross-section A during neap tide (c) and cross-section B during neap tide (d); z† is distance to the mean water surface. Orientation of all the plots is into the estuary

Figure 5 shows the lateral residual flow observed in the two cross-sections. During spring tide, a clockwise transverse residual circulation is observed. Moreover, the maximum northward flow is observed at the surface near the north side, with values of 0.2 m s− 1 (Fig. 5a) in cross-section A and 0.1 m s− 1 in cross-section B (Fig. 5b), respectively. Integrating lateral residual flow over the depth at the end of transects yields a net water transport through the north side. This phenomenon is referred to as water leakage. During neap tide, a more complicated residual circulation pattern is observed. In both cross-sections, a clockwise structure is found over the north shoal. However, in cross-section A, an anti-clockwise circulation is observed over the south shoal (Fig. 5c). In cross-section B, a three-layer structure is observed close to the south side, with southward flow near both the water surface and the bottom and northward flow in the middle water layer. The magnitude of the transverse residual flow has a similar value, of about 0.1 m s− 1 during both spring and neap tides, and it occurs at the surface near the north side (Fig. 5d).

Distribution of lateral residual flow (in cm s− 1) in cross-section A during spring tide (a), cross-section B during spring tide (b), cross-section A during neap tide (c) and cross-section B during neap tide (d); z† is distance to the mean water surface. Unit in contour orientation of all the plots is into the estuary. In panels b and d, positive (negative) values denote northward (southward) flow

2.2 Model

The observations presented in Section 2.1 reveal differences in structure of lateral residual flow and of residual SSC in the two cross-sections during both spring and neap tides. These data add to both observational and model studies that focus on longitudinal distribution of SSC in the Yangtze Estuary (Wu et al. 2012; Jiang et al. 2013; Song and Wang 2013; Wan and Zhao 2017). Differences in each cross-section between spring and neap tides mainly concern the intensity of lateral flow. Thus, these data support the two hypotheses of the present study, which will be tested with an exploratory 3D model.

2.2.1 Model domain

The model domain represents an estuarine channel with two straight parts, connected by a curved segment (Fig. 6). This configuration mimics the gross characteristics of an estuary, like the one considered in Section 2.1. The channel has a constant width, an along-channel uniform bathymetry and open boundaries at both the landward and the seaward end. In the lateral direction, a smooth bottom profile is imposed. The length and half width of channel are denoted by L and B, respectively. A curvilinear x, y and σ −coordinate system is adopted (Fig. 6a), with the origin at the free surface and middle of the landward side section (x = 0). Here, x follows the along-channel direction; y = −B, B are the locations of the northern regulation lines; and σ = (z − ηs)/D, in which z is vertical distance to the undisturbed water surface and z = ηs, is the level of the instantaneous free surface. The bottom is located at z = −h(y) (Fig. 6b). The curvature varies as a function of x and is described by \(R=R_{\min }\breve {R}(x)\), in which Rmin is the minimum radius of the curvature and \(\breve {R}=\left \{\frac {1}{2}+ \frac {1}{2}\text {cos}\left [ \frac {2\pi (x-x_{\text {cur}})}{x_{2}-x_{1}}\right ] \right \}^{-1}\) is a dimensionless function. Here, the limits of the curved segment are denoted by x1 and x2. At xcur = (x1 + x2)/2, the radius of curvature reaches its minimum (Fig. 6c). Note that D = h + ηs is the total instantaneous depth, hence, z = z† + ηs(σ + 1). In the present study, it is assumed that the typical amplitude [ηs] of the instantaneous sea surface elevation is small compared to the undisturbed depth h, i.e. ε ≡ [ηs]/h ∼ 0.1, which implies that z ≃ z†.

Sketch of the model domain: a top view and b side view. A σ-coordinate system (x, y, σ) is used with the origin at the free surface and middle of the landward side, where freshwater input from the river is imposed. The landside entrance (0 km) is located at the reference point (see Fig. 1b). The positive x-axis points seaward, the y-axis points from left to right when looking landward and σ denotes the relative depth from surface (σ = 0) to the bottom (σ = − 1). The bottom profile z = −h(y) is uniform in the x direction and is arbitrary in the y direction. c Dependence of dimensionless function \(\breve {R}^{-1}=R_{\min }/R\) on longitudinal coordinate x, where R is the radius of the curvature and \(R_{\min }\) is the minimum value of R.

2.2.2 Hydrodynamics

Following earlier studies (e.g. Hansen and Rattray 1965), a linear model for steady currents is applied. The Coriolis term in the longitudinal direction is ignored because it is small compared to other terms. The equations for residual flow in 3D σ −coordinates (see Electronic Supplement S1–1 for their derivation) read

Here, Eq. 2a is the longitudinal tidally averaged momentum balance, which contains the barotropic pressure gradient force, the baroclinic pressure gradient force and the internal friction force. Equation 2b is the lateral momentum balance with on its right-hand side the Coriolis force, forces due to barotropic pressure gradient, baroclinic pressure gradient and friction. The superscript ∗ denotes that the horizontal density gradients in both the longitudinal and lateral direction are taken at a fixed z† level. Equation 2c expresses tidally mean conservation of mass. A dimensionless parameter σ0 ≃ z0/h is defined, in which z0 denotes the local roughness length. In these equations, u, v are the tidal mean flow components in the longitudinal and lateral direction, respectively. It is assumed that u and v are zero inside the roughness element layer. The Coriolis parameter f ∼ 10− 4 s− 1 and A v is a spatially varying eddy viscosity and expression will be given in Section 2.2.4. Note that channel curvature can induce lateral residual circulation (Kim and Voulgaris 2008) as well as transport through boundaries (as shown in Section 2.1). The curvature-induced circulation is ignored in the present work, as it is much smaller than that induced by the lateral density gradient (for details see Electronic Supplement S3).

In the model, density gradients are prescribed and values are motivated by field data. First, following Warner et al. (2005), it is assumed that

Here, s∗ (∼ 35 psu) is the salinity at sea, < s > denotes the time-independent cross-sectional mean density, x = L − x c the position at which the salinity is half of its value at sea, and the salinity intrusion limit (where the salinity < s >= 0.12s∗) is at x = L − (x L + x c ). Parameters x c and x L are determined by fitting data to Eq 3. Furthermore, it is used that \(\left (\frac {\partial \rho }{\partial x}\right )^{*} = \beta \frac {\partial <s>}{\partial x}\).

It is further assumed that \(\left (\frac {\partial \rho }{\partial y}\right )^{^{*}}\) is constant in the vertical direction and it is imposed as a function of the lateral distance: \(\left (\frac {\partial \rho }{\partial y}\right )^{^{*}}=a_{r}(y/B)+b_{r}\), in which a r and b r are constants that are determined from the field data. Finally, the aspect ratio of the lateral and longitudinal density gradient is assumed to be constant in the x-direction, i.e. \(\frac { (\partial \rho /\partial y)^{*}}{(\partial \rho /\partial x)^{*}}=\left . \frac {(\partial \rho /\partial y)^{*}}{(\partial \rho /\partial x)^{*}} \right |_{x=x_{\text {m}}}\) with x m being the location where (∂ρ/∂x)∗ attains its maximum value.

The boundary conditions at the free surface and at the bottom are given by

At y = −B, it is assumed that there is no net water transport. At y = B, net water transport is allowed, in order to be able to mimic situations as were discussed in Section 2.1. This results in the following boundary conditions:

Here, q o is a constant water transport (imposed in the model) and f(x) is a dimensionless function that describes the distribution of net water transport in the longitudinal direction. The water leakage through the side, as expressed by the right-hand side of Eq. 5b, occurs when the water elevation is higher than the channel side during part of a tidal cycle. The amount of water leakage at the north side is assumed to be proportional to \(\breve {R}^{-1}\), i.e. the reciprocal of the dimensionless channel curvature. This is because, due to centrifugal forces, surface water layer flows from inner bend to outer bend and causes a set up of water at the outer bend. It is assumed that in the remaining reaches the amount of water lost at the curved segment returns through the north side of the channel with a constant rate q o f c , where \(f_{c}=L^{-1}{\int }^{x_{2}}_{x_{1}} \breve {R}^{-1} \mathrm {d}x\). Hence, f(x) along the channel reads

At the landward entrance, a net transport of freshwater is imposed with a constant discharge Q r ,

2.2.3 Sediment dynamics

Mass conservation of sediment yields an equation for SSC (see Electronic Supplement S1-2), which to a first approximation reads

Here, c is the SSC and ws is the constant settling velocity and Kv is the vertical eddy diffusion coefficient, which will be discussed in the next section. At the surface, there is no flux of sediment,

At the bottom, a vertical turbulent diffusive flux is imposed that describes the amount of sediment being eroded from the bed:

Here, \(\hat {c}\) is a reference concentration, which depends on bottom stress (in principle known) and an as yet unknown sediment availability. Moreover, z a = hσ a is the reference height. For simplicity, σ a = σ0 is chosen. The solution of the SSC equation (Eq. 8) reads

with ϕ(σ, h(y)) describing the vertical distribution of SSC, which can be determined for a given Kv (e.g., if Kv/ws is a constant, ϕ(σ, h(y)) is an exponential function). Note that \(\hat {c}\) is the approximation of the tidally mean bottom SSC. In order to determine \(\hat {c}\), the condition of morphodynamic equilibrium (i.e. averaged over the tidal period, erosion balances deposition of sediment) is applied to the full SSC equation. This implies that the divergence of the sediment transport must vanish, hence

in which T x and T y are the residual sediment transport in the x and y directions, given by

Furthermore, K h x and K h y are constant horizontal eddy diffusion coefficients in the longitudinal and lateral direction and will be further discussed in the next section. In this model, u and v in Eqs. 13a and 13b are residual currents; thus, sediment transport due to tidal pumping is not considered. Substitution of Eq. 11 into Eqs. 12 , 13a and 13b yields an equation for \(\hat {c}\), i.e.

with

Here, I1 and I3 are transports of sediment in the longitudinal and lateral direction in the case of unlimited sediment supply and \(I_{2} \ \partial \hat {c}/\partial x\) and \(I_{4} \ \partial \hat {c}/\partial y\) are transports induced by gradients in the reference concentration.

The conditions for sediment at the two lateral boundaries are

Here, qsed is a given constant sediment transport and function f(x) is described in Eq. 6. Physically, the right-hand side of Eq. 16b represents the amount of sediment leakage at the north side of the channel, which is related to water leakage. Furthermore, sediment transport at the landward entrance is given by

where Qsed is a constant sediment discharge. Finally, it is imposed that

where c b is a given domain averaged near-bed sediment concentration.

2.2.4 Turbulence closure

Previous studies, such as Geyer et al. (2000), have shown that in an unstratified water column the maximum eddy viscosity is usually observed in the middle of the water column, but with increasing stratification, it becomes smaller and its location shifts to the bottom (Geyer et al. 2000). Hence, to capture the basic characteristics of turbulent exchange processes in both weakly stratified (spring tide) and highly stratified (neap tide) situation, a formulation of vertical eddy viscosity is used that depends on σ. The vertical eddy viscosity coefficient follows that of Chen and de Swart (2016),

In this expression, κ = 0.41 is the von Karman’s constant, \(\check {u}_{*}\) is a constant friction velocity, h is depth and A σ describes the dependence of eddy viscosity on coordinate σ. Parameter \(\check {u}_{*}\) is calculated from the expression (for derivation see Electronic Supplement S1–3):

Here, C d ∼ 1 × 10− 3 is a drag coefficient, Ures, Ut and UT = Ures + Ut are characteristic scales of the overall residual flow, tidal flow and total flow. In this study, observations in cross-section A are used to estimate the values for Ures, Ut and UT during spring tide and neap tide, respectively (see Section 2.1).

The function A σ in Eq. 19 reads

with A I = (σ h + 1)(σ p − σ h ) the value of A σ at σ = σ h and A s is the value of A σ at the free surface. A sketch of A σ as a function of σ is presented in Fig. 7. The formulation of A σ contains two input parameters, viz. A s and σ p , with the values determined from field data. The first parameter measures intensity of turbulence at the surface. Based on surface eddy viscosity results from Fig. 2 of Cheng (2014), A s is formulated as \(\text {Log}_{10}(A_{s})=a_{s}(h-h_{\min })h_{\text {mean}}^{-1}+b_{s}\), which describes lower surface eddy viscosity values with increasing water depth. Here as and bs are input parameters. The second parameter is related to the height of the turbulent bottom boundary layer (hb), i.e., hb = (1 + σ p )h (see Fig. 7). As discussed by e.g. Ralston et al. (2008), hb decreases when the water column becomes more stratified. By fitting Eq. 21 to observed vertical eddy viscosities, it was found by Chen and de Swart (2016) that

where Ri is the bulk Richardson number defined in Eq. 1. In this model, Ri is an input parameter and its value will be determined from field data. The values for parameters σ h and A I in Eq. 21 follow by requiring that at σ h both A σ and its derivative ∂A σ /∂σ are continuous.

The vertical diffusion coefficient Kv is calculated as Kv = ScAv, in which Sc is the Schmidt number given as

This choice is based on the results of Munk and Anderson (1948), who presented Eq. 23 in terms of the gradient Ri. Here, the bulk Richardson number is used as an estimation of the gradient Richardson number.

The horizontal turbulent eddy diffusion coefficients in the longitudinal (K h x ) and lateral direction (K h y ) are assumed to have different values. The longitudinal coefficient is due to both vertical and horizontal shear dispersion and the lateral diffusion coefficient is mainly the result of vertical shear dispersion. In tidal estuarine environments, K h x is typically 100 ∼ 200 m2 s− 1 and values of K h y are an order of magnitude smaller (Zimmerman 1986).

2.3 Solutions

As is detailed in Sections S2–1 and S2–2 of the Electronic Supplement, the residual flow reads

The longitudinal residual flow contains two contributions. The first (ud) is driven by the longitudinal density gradient (∂ρ/∂x). The second contribution (u Q ) is induced by the longitudinal net water discharge, which results from two sources: the leakage of water at the north side (Eq. 5b) and the fresh water input at the landward entrance (Eq. 7). In the lateral direction, the residual flow contains three contributions that are due to Coriolis deflection of longitudinal residual flow (fu), the lateral density gradient ∂ρ/∂y and leakage (R), respectively.

The equation and boundary conditions for ϕ = c/ĉ are obtained by substitution of Eq. 11 into Eqs. 8–10 and subsequently dividing all terms by ĉ. After that, integration of the equation and application of the boundary conditions yield an explicit expression for ϕ, which is given in Electronic Supplement S2–3.

To find the solution for the reference sediment concentration ĉ, the morphodynamic equilibrium condition Eq. 14 must be solved. Note that in contrast to previous studies (e.g. Huijts et al. (2006) and Chernetsky et al. (2010)), the equation is two-dimensional. Solutions are obtained by a novel iteration procedure, where in the initial step only the term involving the lateral sediment transport is considered. The error made in the initial step (by ignoring the longitudinal sediment transport) is then compensated at further iteration steps (n = 1, 2, ...). It means that Eq. 14 is solved, where in the first term ĉ at iteration step (n − 1) and in the second term ĉ at step n is used. The details of the iterative procedure and expressions for ĉ are presented in the Appendix.

2.4 Set-up of experiments

First, two experiments were carried out to verify whether the model results is able to mimic the main characteristics of flow and SSC distribution that are also observed in the field. The first experiment is referred to as RS, which describes the reference state at spring tide, and the latter is referred to as RN, which represents the reference case at neap tide. The parameter values used as model input are given in Table 1. These values are representative for the North Passage of the Yangtze Estuary in China, during spring and neap tides, respectively. Parameters that adopted from this study and other references are cited in the footnote of this table.

Next, additional experiments were conducted to verify the first hypothesis, i.e. the longitudinal variation in intensities of the lateral flow components vf, vd and vR are responsible for the longitudinal variation of sediment entrapment in the lateral direction. Settings of the first experiments are the same as that in RS, except that lateral residual flow is only driven by Coriolis deflection of longitudinal residual flow. In the second experiment, the lateral flow is only induced by the density gradient. The third experiment is as RS, but in the lateral direction, only the effect of leakage is accounted for. The fourth experiment is as RS, but it excludes the leakage.

To test the second hypothesis, i.e. that differences in SSC between spring and neap tides mainly concern their intensities, four more experiments were carried out. These experiments were designed like those in the first series, except that parameter values mimic the conditions at neap tide (reference case RN) instead of at spring tide. The details of all experiments are summarised in Table 2.

3 Results

In this section, output of the model in two cross-sections and in one horizontal surface is presented. The first two are sections T1 and T2, and they are located at similar positions as cross-sections A and B in the North Passage of the Yangtze Estuary (see Fig. 1), respectively. The horizontal surface is the σ = − 0.95, located near the bed. The results of the cases RS and RN are shown in Section 3.1, followed by those of the sensitivity experiments in Section 3.2. In Section 3.3, the near-bed SSC distribution results of the experiments is presented.

3.1 Cases RS and RN

Figure 8 shows the modelled transverse distribution of longitudinal and lateral residual flow and of SSC in cross-sections T1 and T2 for case RS. The model results resemble main features of the observed situation at spring tide that were presented in Section 2.1. The longitudinal residual flow (Fig. 8a, b) is mostly seaward at both two cross-sections. Weak landward flow is only found near the bottom of the deep channel. In Fig. 8c, d, the modelled transverse residual flow in T1 and T2 is shown. The panels reveal three main aspects of the observed lateral flow (Fig. 5a, b). First, the circulation is clockwise in both cross-sections, but northward flow is more dominant in T1 than in T2. Second, the maximum residual flow is found both at the surface above the deep channel and near the north side of T1 and T2. Third, the circulation in T2 is weaker than that in T1. Furthermore, the lateral distribution of SSC shows two maxima in T1 and only one near the south shoal in T2 (Fig. 8e, f), which is consistent with the observations (Fig. 2a, b).

Transverse distribution of longitudinal residual flow (a, b), lateral residual flow (c, d) and SSC (e, f) in the RS case (spring tide). The left/right column denotes the model results at in cross-sections T1/T2. Here, z† denotes distance to the mean water surface. Units of values are cm s− 1 in a–d and kg m− 3 in e and f. Orientation of all plots is into the estuary

The results of reference case RN are presented in Fig. 9 and show that the main characteristics of the residual flow and SSC in neap tide are captured by the model as well. Regarding the longitudinal flow, the observed two layer structure (Fig. 4c, d) is reproduced by the model (Fig. 9a, b). In the lateral direction, both the observations (Fig. 5c, d) and model (Fig. 9c, d) show a clockwise circulation, and a maximum northward flow at the surface near the north side. The basic pattern of the modelled SSC (Fig. 9e, f) is similar as that during spring tide (Fig. 8e, f) and consistent with the data (Fig. 2c, d).

Transverse distribution of longitudinal residual flow (a, b), lateral residual flow (c, d) and SSC (e, f) in the RN case (neap tide). The left/right column denotes the model results at in cross-sections T1/T2. Here, z† denotes distance to the mean water surface. Units are cm s− 1 in a–d and kg m− 3 in e and f. Orientation of all plots is into the estuary

3.2 Sediment distribution due to individual mechanisms

Figure 10 displays the modelled transverse distribution of SSC of four different cases (for spring tide condition). In case RS-1, when the lateral flow is only driven by Coriolis deflection of longitudinal flow, SSC slightly increases from the south side to the north side in both T1 and T2 (Fig. 10a, b). On the contrary, if the residual flow is driven by density gradient (RS-2), SSC increases from the north side to the south side (Fig. 10c, d). When the lateral process is due to leakage only (RS-3), the SSC in T1 has a minimum near the south side and it increases towards the north side. The SSC near the north side is much larger than that near the south (Fig. 10e). In T2, the SSC also increases from the south to the north; however, the difference between the two sides is much smaller than that in T1 (Fig. 10f). In case that all flow components are included except the one due to leakage (RS-4), the SSC distributions in the two cross-sections are similar to that of case RS-2, i.e. only one maximum value is observed on the south side (Fig. 10g, h). Comparing the results of these cases with those shown for RS (Fig. 8e, f) reveals that the SSC maxima near the south sides of T1 and T2 are mainly due to the suspended sediment trapping by the lateral density gradient, while the second SSC maximum near the north side of T1 is caused by leakage.

Figure 11 shows the modelled transverse distribution of SSC of four different cases for neap tide condition. Comparing the results with those shown in case RN (Fig. 9e, f) shows that all of the three mechanisms that are investigated in this model are important at T1, in which the Coriolis effect (RN-1) and the leakage (RN-3) cause sediment trapping near the north side while the density gradient (RN-2) pushes sediment to the south side. At T2, high SSC near the south side is mainly caused by the lateral density gradient (Fig. 11d). Note that Coriolis effect causes an increase of SSC from the south side to the north side during neap tide (Fig. 11a, b), which does not occur during spring tide (Fig. 10a, b). When the lateral flow is only driven by the density gradient (Fig. 11c, d) or leakage (Fig. 11e, f), the transverse distribution of SSC shows similar spatial patterns to those during spring tide (Fig. 10c–f), but with smaller SSC values. Results of case RN-4 also show only one SSC maximum on the south side of the two cross-sections, but with values that are much smaller than those of RS-4 (Fig. 10g, h).

Transverse distribution of residual SSC (in kg m− 3) of cases RN-1 (a, b), RN-2 (c, d), RN-3 (e, f) and RN-4 (g, h). The upper panel and lower panel show the results at in T1 and T2, respectively. Here, z† denotes distance to the mean water surface. Unit is kg m− 3. Orientation of all plots is into the estuary

Since the lateral distribution of SSC is induced by residual flow, it is relevant to present the structure of each single flow component. As is shown in (Fig. 12a, b), during spring tide the residual flow induced by Coriolis deflection of longitudinal flow in the two cross-sections shows an anti-clockwise structure, whereas its magnitude is rather small. On the other hand, the density driven flow shows a clockwise structure and is important in both T1 and T2 (Fig. 12c, d). The residual flow due to leakage is northward in the entire cross-section; however, it is only important in T1 (Fig. 12e, f). During neap tide, the residual flow components that are driven by these mechanisms show the same patterns as those during spring tide (not shown).

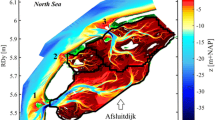

3.3 Near bed SSC distribution in the estuary

The magnitudes of Coriolis induced lateral flow and density driven lateral flow largely vary in the estuary, and thus, changes in the trapping characteristics of residual SSC on the scale of the entire estuary are to be expected. Hence, it is interesting to present an overall picture of SSC distribution in the estuary. Figure 13a displays the near bed (at level σ = − 0.95) SSC distribution for the RS case (spring tide). In this case, the two modelled cross-sections T1 and T2 are located in the core of the turbidity maximum. The zones where SSC is large are found in the middle (30–40 km) and at the seaward boundary, respectively. This results from the joint action of down-estuary sediment transport by the river flow and up-estuary sediment transport by the longitudinal density-driven flow, which has its largest value around 50 km. Moreover, note that in the middle of the estuary, two high SSC values do not appear at the same longitudinal location. The one near the north side is at 35 km and the one on the south side is at 40 km. This difference is attributed to the sediment distribution due to individual lateral flow mechanisms. When the lateral flow is only driven by Coriolis deflection of longitudinal flow, the largest SSC is found at 35 km near the north side (Fig. 13b), whereas if the residual flow is only driven by density gradient, higher SSC values are found on the south side of the estuary with the maximum located at 40 km (Fig. 13c). The sediment trapping caused by leakage also occurs at 35 km at the north side (Fig. 13d). The results of case RS-4 (Fig. 13e, Coriolis and density gradient are included, but no leakage) reveal that there is only one SSC maximum in all cross-sections. At the riverside, SSC has a higher value on the north side than on the south side. Towards the seaside, more sediment is trapped on the south side of the domain. In the lower reach, the value of SSC is larger near the south side than near the north side.

Near bed (level σ = − 0.95) distribution of the SSC (in kg m− 3) in the estuary during spring tide (left column) and during neap tide (right column). Subplots a to e are the results of experiments RS, RS-1 (only Coriolis deflection), RS-2 (only lateral density gradients), RS-3 (only leakage) and RS-4 (Coriolis deflection and lateral density are included, but no leakage). The subplots f to j represent the SSC computed from RN, RN-1, 2, 3 and 4, respectively. The landside entrance (0 km) is located at the reference point (see Fig. 1b). The triangles denote the locations of two modelled cross-sections T1 and T2

In the RN case (neap tide), Fig. 13 shows that the cross-sections T1 and T2 are located downstream of the turbidity maximum. SSC values are high in the middle of the estuary, with local maxima near both lateral sides (Fig. 13(f)). Moreover, Coriolis deflection induced lateral flow causes sediment trapping at 30 km (Fig. 13(g)), which is further up-estuary when compared with that in spring tide (Fig. 13(b)). When the lateral residual flow is driven by across-channel density gradients, the SSC maximum is located at the end of the estuary (Fig. 13(h)). Figure 13i shows the distribution of SSC caused by the lateral flow due to leakage, which is the same as that during spring tide. Finally, Fig. 13j shows the modelled near bed surface SSC distribution for the case RN-4, which is similar to that during spring tide (RS-4).

4 Discussion

4.1 Model assumptions and their connection to field data

The present study focuses on gaining fundamental understanding about longitudinal variations in the lateral trapping of sediment. Therefore, a highly idealised model has been designed that includes a minimum number of processes in order to explain gross aspects of observed residual velocity and turbidity characteristics in the North Passage, a branch of the Yangtze Estuary. The key processes in this model are sediment transport by river flow, density driven flow, leakage and by lateral flow that results from Coriolis deflection of residual longitudinal flow.

By construction, the model yields a simplified view on what happens in real estuaries. In particular with regard to the Yangtze Estuary, analysis of both field data (Li and Zhang 1998; Jiang et al. 2013) and of numerical model output (Song and Wang 2013) indicates that longitudinal trapping of sediment is not only due to gravitational circulation, as is the case in the present model. Other important processes are tidal pumping (i.e. net transport due to the correlation between tidal currents and tidally varying SSC), sediment transport by Stokes return flow and transport by residual flow that results from tidal straining. Other studies also point at the importance of wind (North et al. 2004), stirring of sediment by wind waves at the intertidal areas (Green 2011) and flocculation processes (Winterwerp et al. 2013). Note that in the present model, flocculation is only considered in a simple way, by using different values of settling velocity during spring tide and neap tide.

The presence of Stokes return flow is evident from Fig. 4, which shows the observed structure of longitudinal residual flow at the two transects. During spring tide the Stokes return flow is larger than during neap tide, because it scales quadratically with the tidal amplitude (Ianniello 1977). This explains why the observed discharge through the cross-sections was larger during spring than during neap tide, albeit the river discharge was almost the same at those times.

The reasons to ignore processes in the model other than those included are twofold. First, earlier subtidal models have proven to be remarkably successful in explaining observed amplitudes of the estuarine circulation (Scully et al. 2009) and of lateral and longitudinal distribution of SSC (Huijts et al. 2006; Talke et al. 2009b). The present study further supports the success of subtidal models. Second, adding new processes has to be done with extreme care, as some of them lead to seaward sediment transport (such as Stokes return flow), whereas others result in landward sediment transport (e.g. residual flow due to tidal straining, see Burchard et al. (2013)) and they partially cancel.

There are three other aspects that deserve discussion. First, the observed SSC maxima in the deep channel of the two transects (Fig. 2), especially those during the neap tide, are not captured by the model. This is attributed to the fact that in reality, the channel in the North Passage of the Yangtze Estuary is deep and narrow (compared to the cross-sectional mean depth and width, see Fig. 1). The vigorous tidal currents in the channel stir sediment from the bottom, but the steep slopes prevent the sediment to be laterally distributed. Mimicking that situation in the model is not possible, given the assumptions that nonlinear terms are small (in fact, they scale with the bottom slope), the lateral density gradient is uniform and that sediment transport does not contain a component that is directly forced by bottom slopes.

Second, the assumption that the bottom profile is uniform in the longitudinal direction limits a straightforward application of the present model to estuaries that have strong longitudinal variations in depth, e.g. the Hudson River Estuary (see Fig. 1 of Geyer et al. (2001) ). Depth variations in both lateral and longitudinal directions will result in much more complicated residual flow phenomena (Monismith et al. 2002; Valle-Levinson et al. 2003). For future research, it would be interesting to investigate lateral trapping of sediment at different longitudinal locations in more tidal estuaries.

Third, the depth-integrated net water transport obtained from field data evidently shows a northward directed component at two sampled transects (see Electronic Supplement S4 for details). Note that lateral eddies created by groins that are orthogonal to the channel banks may also contribute to observed leakage. As shown by Ge et al. (2012), these eddies mainly occur in the area between the training walls and the regulation lines. More data at different along-channel positions are needed to quantify the possible contribution of these eddies to leakage.

Moreover, Eq. 6 describes that the water and sediment leaking through the north side in the curved part of the channel is uniformly returned to the channel in the rest of the domain. Compensation for leakage may take place in a different way, and that might affect model results in the straight segment of the estuary. The sensitivity of model results to the way how leakage compensation at lateral boundaries was tested, for the settings of RS and RN, respectively. In these two experiments, water loss due to leakage was compensated by inflow through the south bank. Results (Electronic Supplement S5) show that SSC distributions are slightly changed when comparing with those in default cases (Fig. 13(a, f)). Furthermore, the impact of the formulation for leakage on model results was investigated. The relation between the longitudinal distribution of leakage and channel curvature was generalised as

in which parameter n > 0. When n = 1, Eq. 25 boils down to Eq. 6. The near bed sediment distribution was modelled by using the settings of RS, but for n = 0.5 and 2 in Eq. 25, respectively. Results of these new experiments reveal that the parameterisation of leakage has some local effect on the SSC distribution near the curved segment of the channel, but it does not affect the overall findings presented in the previous sections (Electronic Supplement S5).

4.2 Interpretation of model results

The model results confirm the hypothesis that the different trapping locations of SSC in the estuary result from the variable intensities of lateral flow components at different longitudinal locations. The occurrence of the SSC maxima near the south side of both T1 and T2 is due to the lateral density gradient, while the second SSC maximum near the north side of T1 is due to leakage. Coriolis deflection of longitudinal residual flow also causes trapping of sediment near the north side, but in T1 and T2, it is small compared to the former flow components, both during spring and neap tides. Thus, the difference in lateral pattern of sediment distribution between T1 and T2 is mainly due to the difference in leakage. From Fig. 13, it appears that at other locations in the estuary, different processes are responsible for lateral trapping of sediment. This is because the magnitude of Coriolis induced lateral flow and density driven lateral flow vary on the scale of the entire estuary. As is shown in Fig. 13(a, f), in the upper reach of the estuary, the lateral flow related to Coriolis effects (that causes sediment trapping at the north side, see Fig. 13(b, g)) becomes more important than that driven by the density gradients (that causes sediment trapping on the south side, see Fig. 13(c, h)). As a result, SSC tends to be distributed more uniformly in the lateral direction or becomes slightly larger near the north side. In the lower reach of the estuary, where the density gradients are strong, higher SSC values are obtained near the south side (Fig. 13(e, j)).

The difference in longitudinal locations of SSC maxima at spring and neap tide induced by different flow components (see Fig. 13) is due to the fact that turbulence during spring is more intense than during neap. When the lateral flow is driven by only Coriolis deflection, sediment is trapped near the north side, where during spring tide the longitudinal residual flow is mostly seaward (Fig. 8a, b). During neap tide, this lateral flow is intensified because it experiences less turbulent friction. Moreover, the lower intensity of turbulence causes the larger SSC to be closer to the bed; hence, more sediment is trapped near the north side. Meanwhile, at that time, longitudinal flow (Fig. 9a, b) is landward near the bottom, causing sediment to be moved up-estuary and thus, a landward shift of the SSC maximum occurs. When the lateral flow is driven by the lateral density gradient, intensified residual flow at neap tide (compared to spring tide) causes entrapment of sediment near the south side, which subsequently results in a seaward shift of the location of the SSC maximum.

4.3 Sensitivity of results to values of model parameters

To test the sensitivity of the SSC distribution to the choice of the scaled surface eddy viscosity As (see Section 2.2.4), extra experiments were performed for the setting of RS and RN, respectively. A constant As = 0.005 was imposed, which was obtained by taking cross-sectional mean of As that was used in RS and RN. The transverse distribution of the longitudinal residual flow for a constant As (Fig. 8) shows that the maximum seaward flow is found at the surface above the two shoals instead of at the surface above the deep channel. However, the overall distribution of SSC hardly changes with respect to that of RS and RN, respectively (see Electronic Supplement S5 for details).

The sensitivity of model results to the choice of qsed, Qsed and the formulation of leakage was also tested (figures are presented in Electronic Supplement S5). Two experiments were conducted with the setting of RS, except for qsed = 0.05 kg s− 1 m− 1 and qsed = 0.2 kg s− 1 m− 1, respectively. It turns out that the SSC maxima near the north side increase with smaller qsed and decrease with larger qsed. These results suggest that the appearance of the maximum SSC values at this side is due to the competition between the accumulation of sediment by water leakage and the loss of sediment by its transport through the boundary.

The effect of varying Qsed on the distribution of SSC was investigated by running the model with the setting of RS, but for two more different values of Qsed, viz. 700 kg s− 1 and 900 kg s− 1, respectively. It appears that the different choices of Qsed only quantitatively change the longitudinal distribution of sediment. As Qsed increases, the location of SSC maximum slightly moves up-estuary, whereas for a smaller Qsed, the location of SSC maximum moves down-estuary and more sediment piles up at the seaward boundary.

5 Conclusions

A new three-dimensional exploratory model has been derived and analysed with the objective to gain fundamental understanding of the physics of sediment transport and the presence of turbidity maxima in tidal estuaries. It has been demonstrated the model is able to capture the main features of the observed SSC distribution in two different cross-sections in the North Passage of the Yangtze Estuary during spring and neap tide. In one cross-section (T1), two high values of SSC occur near both south and north sides, while in the cross-section 2 km downstream (T2), only one near the south side was found. Analysis of model results has revealed that the occurrence of the SSC maxima near the south side of both T1 and T2 is due to sediment entrapment by lateral density gradients, while the second SSC maximum near the north side of T1 is due to sediment transport by leakage. Coriolis deflection of longitudinal flow also causes trapping of sediment near the north side, but with less intensity than that of the lateral density driven flow during both spring and neap tides.

Further study of the SSC on the scale of the entire estuary has demonstrated the lateral trapping of sediment depending on intensities of lateral flow due to Coriolis, density gradients and curvature-induced leakage. In the upper reach, where Coriolis deflection of longitudinal flow is important with respect to the lateral density-driven flow, sediment is more uniformly distributed in the lateral direction or trapped near the north side. In the lower reach, lateral density-driven flow is the largest and more sediment is found near the south side. The location of SSC maxima due to the residual flow that induced by leakage remains at the same location, i.e. the position where the radius of the channel curvature attains the minimum, in both spring and neap tides. In the case without leakage, there is only one SSC maximum in the lateral direction at all longitudinal locations. It occurs on the north side in the upper reach. Further seaward, more sediment is found on the south side of the cross-section.

References

Burchard H, Bolding K, Villarreal MR (2004) Three-dimensional modelling of estuarine turbidity maxima in a tidal estuary. Ocean Dyn 54:250–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10236-003-0073-4

Burchard H, Schuttelaars HM, Geyer WR (2013) Residual sediment fluxes in weakly-to-periodically stratified estuaries and tidal inlets. J Phys Oceanogr 43:1843–1860. https://doi.org/10.1175/JPO-D-12-0231.1

Chen SN, Sanford L (2009) Lateral circulation driven by boundary mixing and the associated transport of sediments in idealised partially mixed estuaries. Cont Shelf Res 29:101–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2008.01.001

Chen W, de Swart HE (2016) Dynamic links between shape of the eddy viscosity profile and the vertical structure of tidal current amplitude in bays and estuaries. Ocean Dyn 66:299–312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10236-015-0919-6

Chen Z, Le J (2005) Regulation principle of the Yangtze River Estuary deep channel. Hydro-science Eng 1:1–7. (in Chinese with English abstract)

Cheng P (2014) Decomposition of residual circulation in estuaries. J Atmos Oceanic Technol 31(3):698–713. https://doi.org/10.1175/JTECH-D-13-00099.1

Chernetsky A, Schuttelaars HM, Talke SA (2010) The effect of tidal asymmetry and temporal settling lag on sediment trapping in tidal estuaries. Ocean Dyn 60:1219–1241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10236-010-0329-8

Cloern JE, Foster SQ, Kleckner AE (2013) Review: phytoplankton primary production in the world’s estuarine-coastal ecosystems. Biogeosci Discuss 10:17,725–17,783. https://doi.org/10.5194/bgd-10-17725-2013

Donker JJA, de Swart HE (2013) Effects of bottom slope, flocculation and hindered settling on the coupled dynamics of currents and suspended sediment in highly turbid estuaries, a simple model. Ocean Dyn 63(4):311–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10236-013-0593-5

Dyer KR (1997) Estuaries: a physical introduction, 2nd edn. Wiley, Chichester, p 195

Festa JF, Hansen DV (1978) Turbidity maxima in partially mixed estuaries: a two-dimensional numerical model. Estuar Coast Mar Sci 7:347–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/0302-3524(78)90087-7

Geyer WR (1993) The importance of suppression of turbulence by stratification on the estuarine turbidity maximum. Estuaries 16:113–125. https://doi.org/10.2307/1352769

Geyer WR, Trowbridge JH, Bowen M (2000) The dynamics of a partially mixed estuary. J Phys Oceanogr 30:2035–2048

Geyer WR, Woodruff JD, Traykovski P (2001) Sediment transport and trapping in the Hudson River estuary. Estuar Coast 24:670–679. https://doi.org/10.2307/1352875

Green MO (2011) Very small waves and associated sediment resuspension on an estuarine intertidal flat. Est Coast Shelf Sci 93:449–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2011.05.021

Hansen DV, Rattray MJ (1965) Gravitational circulation in straits and estuaries. J Mar Res 23:104–122

Huijts KMH, Schuttelaars HM, de Swart HE, Valle-Levinson A (2006) Lateral entrapment of sediment in tidal estuaries: an idealized model study. J Geophys Res 111:C12,016. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JC003615

Ianniello JP (1977) The distribution of shearing stresses in a tidal current. J Mar Res 35:755–786

Jay DA, Musiak JD (1994) Particle trapping in estuarine tidal flows. J Geophys Res 99:20 461:445–20. https://doi.org/10.1029/94JC00971

Jiang C, de Swart HE, Li J, Liu G (2013) Mechanisms of along-channel sediment transport in the North Passage of the Yangtze Estuary and their response to large-scale interventions. Ocean Dyn 63:283–305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10236-011-0414-7

Jiang Z, Chen J, Zhou F, Shou L, Chen Q, Tao B, Yan X, Wang K (2015) Controlling factors of summer phytoplankton community in the Changjiang (Yangtze River) Estuary and adjacent East China Sea shelf. Cont Shelf Res 101:71–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2015.04.009

Kim YH, Voulgaris G (2008) Lateral circulation and suspended sediment transport in a curved estuarine channel: Winyah Bay, SC, USA. J Geoph Res 113:C09,006. https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JC004509

Li J, Zhang C (1998) Sediment resuspension and implications for turbidity maximum in the Changjiang Estuary. Mar Geol 148:117–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-3227(98)00003-6

Liu G, Zhu J, Wang Y, Wu H, Wu J (2011) Tripod measured residual currents and sediment flux: impacts on the silting of the deepwater navigation channel in the Changjiang estuary. Est Coast Shelf Sci 93:192–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2010.08.008

May CL, Koseff JR, Lucas LV, Cloern JE, Schoellhamer DH (2003) Effects of spatial and temporal variability of turbidity on phytoplankton blooms. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 254:111–128. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps254111

Monismith SG, Kimmerer W, Burau JR, Stacey MT (2002) Structure and flow-induced variability of the subtidal salinity field in northern San Francisco Bay. J Phys Oceanogr 32:3003–3019

Munk WH, Anderson ER (1948) Note on the theory of the thermocline. J Mar Res 7:276–295

North E, Chao S, Sanford L, Hood R (2004) The influence of wind and river pulses on an estuarine turbidity maximum: numerical studies and field observations in Chesapeake Bay. Estuar Coast 27:132–146

Postma H (1967) Sediment transport and sedimentation in the estuarine environment. Proc Am Assoc Adv Sci 83:158–179

Ralston DK, Geyer WR, Lerczak JA (2008) Subtidal salinity and velocity in the Hudson River Estuary: observations and modeling. J Phys Oceanogr 38:753–770. https://doi.org/10.1175/2007JPO3808.1

Sanford L, Suttles SE, Halka JP (2001) Reconsidering the physics of the Chesapeake Bay estuarine turbidity maximum. Estuaries 24:655–669. https://doi.org/10.2307/1352874

Schubel JR, Carter HH (1984) The estuary as a filter for fine-grained suspended sediment. In: The estuary as a filter. Elsevier, pp 81–105

Schuttelaars HM, de Jonge VN, Chernetsky A (2013) Improving the predictive power when modelling physical effects of human interventions in estuarine systems. Ocean Coast Manage 79:70–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2012.05.009

Scully ME, Geyer WR, Lerczak JA (2009) The influence of lateral advection on the residual estuarine circulation: a numerical modeling study of the Hudson River Estuary. J Phys Oceanogr 39:107–124. https://doi.org/10.1175/2008JPO3952.1

Shi JZ (2004) Behaviour of fine suspended sediment at the North passage of the Changjiang Estuary, China. J Hydrol 293:180–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2004.01.014

Shi Z, Zhou HJ, Eittreim SL, Winterwerp J (2003) Settling velocities of fine suspended particles in the Changjiang Estuary, China. J Asian Earth Sci 22:245–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1367-9120(03)00067-1

Song D, Wang X (2013) Suspended sediment transport in the Deepwater Navigation Channel, Yangtze River Estuary, China, in the dry season 2009: 2. Numerical simulations. J Geophys Res 118:5568–5590. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrc.20411

Talke SA, de Swart HE, de Jonge VN (2009a) An idealized model and systematic process study of oxygen depletion in highly turbid estuaries. Estuar Coast 32:602–620. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-009-9171-y

Talke SA, de Swart HE, Schuttelaars HM (2009b) Feedback between residual circulation and sediment distribution in highly turbid estuaries: an analytical model. Cont Shelf Res 29:119–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2007.09.002

Valle-Levinson A, Reyes C, Sanay R (2003) Effects of bathymetry, friction, and rotation on estuary–ocean exchange. J Phys Oceanogr 33:2375–2393

van Maren DS, Oost AP, Wang Z, Vos PC (2016) The effect of land reclamations and sediment extraction on the suspended sediment concentration in the Ems Estuary. Mar Geol 376:147–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2016.03.007

Wan Y, Zhao D (2017) Observation of saltwater intrusion and ETM dynamics in a stably stratified estuary: the Yangtze Estuary, China. Environ Monit Assess 189:89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-017-5797-6

Wang Y, Gao J, Pan S (2006) Measurement of bottom boundary layer parameters of the Yangtze River Estuary. Marine Geology Lett 22:16–20. (in Chinese with English abstract)

Warner JC, Geyer WR, Lerczak JA (2005) Numerical modeling of an estuary: a comprehensive skill assessment. J Geophys Res 110:C05,001. https://doi.org/10.1029/2004JC002691

Winterwerp J, Wang Z, van Braeckel A, van Holland G, Kösters F (2013) Man-induced regime shifts in small estuaries - ii: a comparison of rivers. Ocean Dyn 63(11-12):1293–1306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10236-013-0663-8

Wu J, Wang Y, Cheng H (2009) Bedforms and bed material transport pathways in the Changjiang (Yangtze) Estuary. Geomorphology 104:175–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2008.08.011

Wu J, Liu JT, Wang X (2012) Sediment trapping of turbidity maxima in the Changjiang Estuary. Mar Geol 303:14–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2012.02.011

Yang Z, de Swart HE, Cheng H, Jiang C, Valle-Levinson A (2014) Modelling lateral entrapment of suspended sediment in estuaries - The role of spatial lags in settling and M4 tidal flow. Cont Shelf Res 85:126–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2014.06.005

Zhu Z, Zhang J, Wu Y, Zhang Y, Lin J, Liu S (2011) Hypoxia off the Changjiang (Yangtze River) Estuary: oxygen depletion and organic matter decomposition. Mar Chem 125 (1):108–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marchem.2011.03.005

Zimmerman JTF (1986) The tidal whirlpool: a review of horizontal dispersion by tidal and residual currents. Neth J Sea Res 20:133–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/0077-7579(86)90037-2

Funding

The first author is financially supported by the China Scholarship Council. This work is supported by the project NSFC-51479074 and the observational data are provided by Yuanye Wang in Shanghai Estuarine and Coastal Science Research Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Bram C. van Prooijen

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 A Iterative method to construct approximate solutions for ĉ

Equation 14 is rewritten in terms of a scaled reference concentration \(\alpha =\hat {c}/c_{b}\) and a formal ordering parameter 𝜖 (= 1) is introduced, this yields

with boundary conditions

The solution for α and the transport of sediment in the x and y directions are written as formal series in parameter 𝜖(= 1), i.e.

in which the superscript/subscript n = 0, 1, 2,... denotes the iteration step. Substituting Eq. 28 into Eqs. 26 and 27, then collecting terms with equal order of 𝜖n yields the equations at different iteration steps.

At the initial step (n = 0),

The solution reads

Note that F y depends on x and y. The integration coefficient \(\hat {\alpha }_{0}(x)\) is determined by analysing Eq. 26 at the next iteration step (n = 1):

with boundary conditions

Integrating Eq. 32 over the lateral direction and using the boundary conditions at the lateral sides and then from the riverside boundary down-estuary yields

with \(G(x)=Q_{\text {sed}}-q_{\text {sed}}{{\int }^{x}_{0}}f(\tilde {x})\mathrm {d}\tilde {x}\). Substitution of Eq. 31 into Eq. 34 yields

in which, \({\Gamma }_{a}={\int }^{B}_{-B}I_{2}F_{y}\mathrm {d}y\) and \({\Gamma }_{b}={\int }^{B}_{-B}\left (I_{1}F_{y}+I_{2}\frac {\partial F_{y}}{\partial x} \right )\mathrm {d}y\) are functions of x. The solution for Eq. 35 reads

Thus, α is subject to an unknown integration constant γ0, which is determined by using the constraint Eq. 30. The result is

If the iteration is truncated at the initial step, one error made at this stage is ∂Tx,0/∂x. The equations for n ≥ 2 read:

with boundary conditions

By integrating Eq. 38 from y = −B to y and using the boundary condition that there is no sediment across the south side (y = −B), the solution reads

In Eq. 40, the unknown function \(\hat {\alpha }_{n}(x)\) is found as follows: First, substituting Eq. 40 into Eq. 38 but for n + 1. Second, integrating the obtained equation from − B to B and then from x = 0 to x and using the corresponding constraints in Eq. 39. The solution reads

in which \({\Gamma }_{n}={\int }^{B}_{-B}\left (I_{1}F_{n}+I_{2}\frac {\partial F_{n}}{\partial x} \right )\mathrm {d}y\). Finally, the unknown constant γ n is determined by using the last constraint of Eq. 39. The result is

The change between two iteration steps is defined as \(\xi =\frac {\left [{\sum }^{n-1}_{i = 0}\alpha _{i} \right ]_{\max }}{\left [{\sum }^{n}_{i = 0}\alpha _{i} \right ]_{\max }}\). The iterative process is terminated when ξ ≤ 0.1.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, W., de Swart, H.E. Longitudinal variation in lateral trapping of fine sediment in tidal estuaries: observations and a 3D exploratory model. Ocean Dynamics 68, 309–326 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10236-018-1134-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10236-018-1134-z