Abstract

Although most individuals experience expectation violations in their educational years, individuals’ coping strategies differ depending on situational and dispositional characteristics with potentially decisive influence on educational outcomes. As a situational characteristic, optimism bias indicates that individuals tend to update their expectations after unexpected positive feedback and to maintain their expectations after unexpected negative feedback. As a dispositional characteristic, a higher need for cognitive closure (NCC) indicates that individuals tend to both update (accommodation) and try to confirm expectations (assimilation) after unexpected negative feedback. To better understand mechanisms behind optimism bias and context-dependent effects of NCC in an educational context, we included controllability (attribution of success/failure to internal or external causes) and self-enhancement (amplifying positive self-relevant aspects) in an experimental case vignettes study. Our sample of n = 249 students was divided into four experimental groups (high/low controllability × positive/negative valence) and read four different case vignettes referring to expectation violations in an educational context. MANCOVA revealed that individuals updated their expectations after unexpected positive feedback only with stronger (vs. weaker) self-enhancement and that individuals maintained their expectations after unexpected negative feedback in controllable (vs. uncontrollable) situations. Furthermore, interindividual differences in NCC interacted with controllability in predicting expectation update. We conclude that considering the influences of controllability and self-enhancement, we can better understand and evaluate the adaptivity of the optimism bias and context-dependent effects of NCC in an educational context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Individuals constantly form expectations about themselves and their environment and nearly all individuals have educational expectations, as education is a central part of the identity for many individuals (e.g., Goossens, 2001; van Doeselaar et al., 2018). Educational expectations refer to anticipated future achievement (Pinquart & Ebeling, 2020) and are important predictors of a whole range of short- and long-term outcomes such as effort (Schoon & Ng-Knight, 2017) and academic attainment (Carolan, 2017). But educational expectations tend to be overly optimistic (Carolan, 2017; Hacker et al., 2000; Pinquart & Pietzsch, 2022; Reynolds & Baird, 2010) and individuals cannot fully influence actual situational outcomes — as they for example do not exactly know what will be asked in exams. Therefore, individuals can experience situations in which their educational expectations are violated, leading to cognitive dissonance and heightened physiological arousal (Mendes et al., 2007). To resolve this state, individuals need to cope with the expectation violation, but coping strongly varies depending on situational characteristics and personality dispositions (Panitz et al., 2021). Regarding situational characteristics, previous research indicates that unexpected positive feedback is typically accepted, leading to expectation update, whereas unexpected negative feedback is often rejected, leading to expectation maintenance (e.g., Garrett & Sharot, 2017; Kube & Glombiewski, 2021; Lefebvre et al., 2017). This coping asymmetry is known as the optimism bias (Sharot, 2011). Also regarding personality dispositions, individuals with a higher need for cognitive closure (NCC) perceive expectation violations as especially aversive because they are less able to tolerate the inherent uncertainty (Roets & van Hiel, 2011; Webster & Kruglanski, 1994). Therefore, coping likely varies between individuals with higher vs. lower NCC. Both the optimism bias as well as NCC have been explored previously and have left some open questions that this study aims to address. For optimistically biased coping, we could only find stronger expectation maintenance after unexpected negative feedback but could not confirm stronger expectation update after unexpected positive feedback. For coping with higher vs. lower NCC, we found strongly context-dependent effects on both stronger expectation update and expectation maintenance (Henss & Pinquart, 2022, 2023). For a better understanding of the effects of both predictors, we aim to incorporate the predictors controllability and self-enhancement to gain insight into the mechanisms underlying these coping responses. Theoretically, the findings of this study aim to enhance our understanding of the optimism bias, clarify contradictory results in the educational context, and shed light on the context-dependent effects of NCC. Practically, our results should help to identify possible dysfunctional coping responses and to determine risk and protective factors for coping with violated educational expectations. This requires experimental paradigms on expectation violations in educational contexts that incorporate multiple situational and dispositional characteristics and examine their interaction, which have been neglected in previous research.

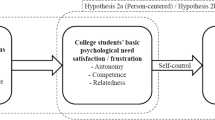

Educational expectations and the ViolEx model

The ViolEx model (Violated Expectations Model; Gollwitzer et al., 2018; Panitz et al., 2021; see Fig. 1) was originally developed as an explanatory model for the lack of positive expectation update in depression (Rief et al., 2015) and also has been successfully applied in the educational context to better understand coping processes in elementary school children following negative feedback (Pinquart & Block, 2020), the influence of parental expectations on performance changes in children (Pinquart & Ebeling, 2020), and classroom management strategies for children with ADHD (Strelow et al., 2020). The ViolEx model is a general psychological framework defining expectations as conditional predictions about future events and explaining how expectations are formed, stabilized, maintained, or changed (Panitz et al., 2021). As illustrated in the ViolEx model in Fig. 1, individuals have generalized, cross-situational expectations referring to what students realistically expect to achieve in education and academia (see box “Generalized Expectation”; Pinquart & Ebeling, 2020). In specific situations, such as exams or assignments, situation-specific expectations derive from generalized educational expectations, meaning that a student with strongly positive educational expectations will likely expect positive results in an upcoming exam (see box “Situation-Specific Expectation” in Fig. 1).

ViolEx model by Panitz et al., 2021 (p. 7)

But past research has shown that the situational outcomes will not always match with initial expectations, as individuals tend to hold overly optimistic educational expectations (Carolan, 2017; Hacker et al., 2000; Pinquart & Pietzsch, 2022; Reynolds & Baird, 2010). Over the course of an educational career, individuals will repeatedly face stressors such as unexpected feedback or unexpected grades in exams or assignments, and these expectation violations can result in lower first-year GPA scores (Smith & Wertlieb, 2005), higher stress (Krieg, 2013), and higher drop-out intentions (Gerdes & Mallinckrodt, 1994). Therefore, adaptive coping with unexpected feedback can be decisive to success or failure (Skinner et al., 2013; Skinner & Saxton, 2019). In the academic context, adaptive coping strategies support students’ continued participation in learning activities, provide opportunities for knowledge acquisition, and result in higher academic achievement and higher perceived competence (Gonçalves et al., 2019; Skinner et al., 2013; Skinner & Saxton, 2019). Furthermore, adaptive coping aims to decrease the likelihood of future expectation violations to avoid uncertainty, cognitive dissonance, and heightened arousal.

The ViolEx model states different possible responses to expectation violations (Panitz et al., 2021). Individuals can anticipate expectation violations and increase the probability of expectation confirmation through active behavior (assimilation; see box “Internal Anticipatory Reaction and External Anticipatory Reaction” in Fig. 1). For example, when anticipating or receiving a negative result, they can improve their learning behavior to avoid future negative feedback. Also, they can deny or devalue unexpected feedback (immunization), for example by perceiving an unexpected grade to be an exception. Both assimilation and immunization result in the maintenance of prior expectations. Contrary, individuals can update their expectations in line with unexpected feedback (accommodation), for example by expecting a better grade in the next exam after receiving unexpected positive feedback. Expectation update leads to an adaption of generalized expectations and therefore, to adjusted situation-specific expectations next time. None of these coping responses can universally be labeled as adaptive or maladaptive; instead, they always have to be considered context-dependent in relation to dispositional and situational characteristics (Thompson, 2015; Zeidner, 1995), such as valence and NCC (see box “Social and Personal Influences” in Fig. 1).

The optimism bias

A major influence on how individuals cope with unexpected feedback is the valence-related optimism bias. Previous research indicates that individuals accommodate more strongly after receiving unexpected positive feedback and assimilate or immunize more strongly after receiving unexpected negative feedback (e.g., Garrett & Sharot, 2017; Kube & Glombiewski, 2021; Lefebvre et al., 2017). Especially in the clinical context, there is a considerable amount of research on expectation update vs. maintenance, indicating that healthy individuals positively update their expectations after receiving positive feedback, but maintain their expectations after receiving negative feedback by questioning its credibility or perceiving it as an exception (e.g., Kube & Glombiewski, 2021; Kube et al., 2019). This is probably because the valence of unexpected feedback results in different affective states (Green et al., 2005; Hepper et al., 2013; Zingoni & Byron, 2017): unexpected negative feedback can be perceived as aversive and threatening, whereas unexpected positive feedback can be perceived as satisfying and pleasant (Shanahan et al., 2020). Regarding the educational context, individuals are also confronted with unexpected positive vs. negative feedback, and optimistically biased coping could support positive educational expectations and lead to adaptive outcomes (such as continued effort or positive affect, even after setbacks) associated with positive expectations (Pinquart & Pietzsch, 2022; Shanahan et al., 2020). But recent research has failed to confirm that unexpected positive feedback results in stronger accommodation (Henss & Pinquart, 2022, 2023), and this study aims to include additional predictors that may interact with the optimism bias and help to understand the (lack of) effects.

The optimism bias and self-enhancement

Potentially, the optimism bias could be supported by individuals’ tendencies for self-enhancement. Self-enhancement refers to the human inclination to amplify positive aspects of oneself and downplay negatives ones, driven by a desire for personal satisfaction and the maintenance of a positive self-concept (Caprar et al., 2016; Hay et al., 1999; Hepper et al., 2010). A strategy for self-enhancement is to use favorable construals which consist of selective processing of (positive) feedback and self-serving interpretations of feedback (Hepper et al., 2013). For example, favorable construals may refer to over-optimistic positive self-evaluations (e.g., to be better than average in all study-relevant fields): positive feedback is less aversive compared with negative feedback and therefore more likely to be accepted, whereas negative feedback is more likely to be ignored (Caprar et al., 2016). This expectation update vs. maintenance is in line with the assumed optimism bias, and maybe for accommodation, feedback needs to actually be processed and internalized to result in the stronger accommodation. Therefore, we hypothesized that after receiving unexpected positive feedback, individuals with stronger self-enhancement will report stronger accommodation compared with lower self-enhancement. Contrary, after receiving unexpected negative feedback, individuals with stronger self-enhancement will report higher immunization compared with lower self-enhancement.

The optimism bias and controllability

Furthermore, individuals might be less likely to report stronger accommodation after unexpected positive feedback if they do not perceive internal causes such as their effort as the reason for the positive outcome, but external circumstances such as luck or coincidence. If the expectation violation is attributed to external causes and therefore uncontrollable, individuals might refuse to accommodate to avoid a renewed and then negative expectation violation. Controllability in the educational context refers to students’ belief in their influence over academic success or failure (Respondek et al., 2017). According to the attributional theory, individuals attribute success and failure to internal or external causes (Weiner, 1985), depending on how much they are able to control them (Zimmerman & Schunk, 2006). These attributions play a crucial role in academic settings and influence well-being (Zhang et al., 2014) and future behavior (Weiner, 2000). Also, higher controllability is linked to several adaptive educational outcomes such as higher academic success and lower risk for dropout of university (Respondek et al., 2017). With higher perceived controllability, the optimistic bias is particularly pronounced (Jansen, 2016) and academic-related optimism bias can be beneficial for achievement and performance if accompanied by a sense of control (Ruthig et al., 2007). Therefore, controllability and valence are likely to be related in explaining adaptive and maladaptive coping with violated educational expectations. We hypothesized that with low controllability (especially in interaction with negative valence), individuals will be more likely to report stronger immunization because they attribute the expectation violation to external causes. Contrary, with high controllability, individuals will be more likely to report stronger assimilation (e.g., more effort) as well as accommodation because they attribute the expectation violation to internal causes.

Need for cognitive closure

In addition to situational characteristics, the personality disposition NCC proved to be a decisive predictor for coping with expectation violations in the educational context in previous studies (Henss & Pinquart, 2022, 2023). Individuals with a high NCC experience expectation-violating situations as particularly aversive because they are accompanied by uncertainty (e.g., Kossowska et al., 2010; Webster & Kruglanski, 1994). Therefore, individuals with high NCC should have a particularly strong need to resolve or at least minimize the resulting cognitive dissonance with appropriate coping strategies. But individuals with higher NCC seem to differ in their use of coping strategies depending on context and situational characteristics: Previous studies found stronger expectation maintenance (immunization and assimilation) for individuals with higher NCC (Dijksterhuis et al., 1996; Kossowska et al., 2010), but contrary to prior studies, higher NCC did not lead to stronger immunization in the educational context (Henss & Pinquart, 2022, 2023). Presumably, the educational context differs from the mentioned previous study results in which expectations were related to beliefs about the world or outgroups because of its focus on oneself and one’s successes and failures. Whereas it might be easier to avoid receiving or simply ignoring expectation-discrepant information about other groups, individuals can hardly avoid receiving or simply ignore self-relevant feedback. Instead, results in the educational context indicated a coping pattern that combined both active behavior to fulfill expectations (assimilation) and, surprisingly, also the update of expectations (accommodation). Therefore, despite the assumed tendency to maintain prior expectations (Neuberg & Newsom, 1993), individuals with higher NCC can actually reduce uncertainty when processing information that contradicts expectations (Strojny et al., 2016). Individuals do not maintain expectations if it does not contribute to reducing uncertainty or when inconsistent information is diagnostically more relevant (Schrackmann & Oswald, 2014; Strojny et al., 2016). Combining both strategies might be particularly adaptive to avoid future expectation violations, as behavior is adjusted to fulfill existing expectations but also expectation adjustment takes place to avoid future disappointment. This suggests that the stable individual difference NCC (Dijksterhuis et al., 1996) can vary depending on the situational characteristics of expectation violations such as controllability (Kossowska et al., 2010; Webster & Kruglanski, 1997). With the inclusion of controllability as a predictor, we might enhance the understanding of the adaptivity of this significant, but until now surprising effect of NCC on accommodation and assimilation. With higher controllability, individuals with higher NCC might experience expectation violations as less aversive compared to low controllability because the sense of control mitigates uncertainty and individuals can rely on internal, stable causes. Contrary, low controllability might even enhance the uncertainty and perceived aversiveness because of external, unstable causes. Keeping in mind that individuals with higher NCC might be especially vulnerable after receiving unexpected feedback, we aim to explore how controllability and NCC interact to identify the adaptiveness of coping responses.

The present study

Expectation violations can refer to a variety of situations in the educational context. We selected some of these situations and presented them to students in case vignettes. In doing so, we expected both dispositional and situational characteristics as well as their interplay to affect how students cope with expectation violations. We aim to answer the following research questions:

-

1)

Is there an optimism bias in coping with violated academic expectations?

To answer this research question, we first of all assumed that students report stronger assimilation after unexpected negative feedback compared with unexpected positive feedback (hypothesis 1). Also, when the expectation-violating situation is not controllable, students were expected to report more immunization than in controllable situations (hypothesis 2). However, we were particularly interested in the interactions of valence with self-enhancement and controllability to better understand the optimism bias. We hypothesized that the interaction of negative valence and low controllability of the expectation violation leads to stronger immunization (hypothesis 3), whereas the interaction of negative valence and high controllability leads to stronger accommodation and assimilation (hypothesis 4). Practically, this means that if an exam grade is worse than expected and students had no control over it (e.g., due to incomprehensible evaluation criteria), they are more likely to consider this expectation violation as an exception and to immunize. However, if they had control over their worse performance (e.g., due to inadequate preparation), they are more likely to change both their behavior and also their expectations. Also, individuals with a stronger tendency for self-enhancement should be more likely to report stronger immunization after negative feedback (hypothesis 5). After unexpected positive feedback, on the other hand, we hypothesized that stronger accommodation is found only when individuals use feedback for self-enhancement (hypothesis 6). In practical terms, this means that an unexpectedly good exam only leads to higher expectations about the future if individuals show a stronger tendency for self-enhancement.

-

2)

Does higher NCC lead to context-dependent differences in coping?

We assumed that in line with our previous results, students with higher NCC will report stronger accommodation and assimilation (hypothesis 7). Furthermore, we aim to explore how the controllability of the situation influences coping with expectation violations because uncontrollable situations should be perceived as more aversive for individuals with high NCC than for individuals with lower NCC. Therefore, we assumed an interaction between NCC and controllability on coping (exploratory hypothesis).

Methods

The study was approved by the local ethics committee of Philipps University in Marburg, Germany (reference number 2022-68 k). All participants confirmed written informed consent and were treated according to the ethical guidelines of the German Psychological Society and the Declaration of Helsinki. In addition, the study was preregistered after data collection in the Open Science Framework (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/6A8G9) and supplementary material can be found online (osf.io/2xkms/).

Participants

To estimate the required number of participants, an a priori sample size analysis was conducted using G*Power. Power analysis was performed for both main effects (MANOVA: f2 = 0.03; α = 0.05; ß = 0.90; 4 groups, 3 outcomes) and interaction effects (MANOVA: f2 = 0.03; α = 0.05; ß = 0.90; 4 groups, 3 predictors, 3 outcomes). We expected a small effect for the experimental manipulation in accordance with our former results in similar studies (Henss & Pinquart, 2022, 2023). The analysis resulted in a required sample size of at least 224 participants. We stopped recruitment after 270 participants to account for possible exclusions and still achieve adequate power. Participants were recruited throughout Germany via email distribution lists of universities. Inclusion criteria were good German language skills and legal age. As compensation, participants could receive course credit or take part in a raffle for 4 × 25€ vouchers.

Randomization

The 20-min online experimental study was conducted via SoSciSurvey as a 2 × 2 between-subjects design. The predictors valence (negative vs. positive) and controllability of expectation violation (high vs. low) were manipulated, resulting in four experimental groups: positive valence and high controllability, positive valence and low controllability, negative valence and high controllability, and negative valence and low controllability. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the four experimental groups by computer without their knowledge.

Procedure

At the beginning of the study, sociodemographic data and personality traits (academic self-concept and need for cognitive closure) were collected. Subsequently, the participants received instructions on how to process the case vignettes. They were informed that in the following, they would be presented with four different scenarios from the university context. Their task was to read them and to imagine how they would behave in the situation described. Each group received the same four scenarios (exam grade, job interview, lecture, written assignment), which differed only in the manipulated valence and controllability. The case vignettes consisted of 8–10 sentences and described a positive or negative expectation violation whose outcome could either have been controlled or not affected by the participant (see Supplementary Material, Appendix A). After each case vignette, subjects were asked about how they would have coped with the described situation. At the end of the questionnaire, a scale for self-enhancement was additionally presented; here, the participants were instructed to recall the four case vignettes and answer accordingly to how they felt about the situation. Finally, a manipulation check was performed for controllability and valence, and questions were asked about the processing of the study (seriousness, presumed study goal). After the questionnaire was completed, we informed the participants about the actual purpose of the study.

Measures

Socio-demographics

We assessed age, gender, and the current semester of study.

Academic self-concept

We assessed the academic self-concept with the “General academic self-concept” scale from Arens et al. (2021). The scale consisted of three items (e.g., “My performance at university has been good so far”) and was measured on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. Cronbach’s alpha was good with α = 0.83.

Need for cognitive closure

NCC was assessed with the 16 NCCS (Schlink & Walther, 2007). The scale contains 16 items (e.g., “I do not like unpredictable situations”). As a rating scale, we used a 7-point Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. Cronbach’s alpha was good with α = 0.79.

Coping strategies

After each case vignette, eight items were used to assess coping with the presented expectation violations. Two items addressed assimilation (e.g., “I will align my efforts with my expectations on the next exam.”), three items addressed accommodation (e.g., “On the next exam, I will change my expectation according to my actual performance”), and three items were related to immunization (e.g., “The feedback I received in the exam was an exception”). These eight items were previously used in other studies (Henss & Pinquart, 2022, 2023) and were adapted to the four scenarios. In the end, the items on each of the three coping styles were combined, so that assimilation was assessed with a total of eight items and accommodation and immunization with 12 items each. Participants responded on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. Cronbach’s alpha was very good for all three scales with α = 0.89 for accommodation, α = 0.86 for assimilation, and α = 0.87 for immunization.

Self-enhancement

At the end of the survey, we presented the five items of the Self-Enhancement subscale “Favorable Construals” (Hepper et al., 2013) to elicit self-enhancement (e.g., “You think of yourself as generally possessing positive personality traits or abilities to a greater extent than most people”). We used the favorable construals subscale because the items provided a good fit with our case vignettes and can refer to both unexpected positive and negative feedback. Again, self-enhancement was assessed with a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. Cronbach’s alpha was good with α = 0.80.

Manipulation Check

To be able to attribute the effects of valence and controllability to the manipulation, we controlled for whether the manipulated variables induced the intended differences at the end of the study.

In the manipulation control of valence, participants rated the outcome of the scenarios on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 = very negative to 7 = very positive (“How did you feel about the outcome of the situations described?”).

To assess the degree of induced controllability, subjects were also asked to indicate how controllable they felt the situation was on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 = very little to 7 = very much after each case vignette and generally at the end of the survey (e.g., “How much do you think you could have influenced the outcome of the situations described?”).

Data analysis

To calculate the main statistical effects of the predictors valence and controllability and interaction effects with the covariates NCC and self-enhancement, we performed a MANCOVA with the three coping strategies accommodation, assimilation, and immunization as outcomes at a significance level of 5%.

Results

Participants

From n = 270 participants, we had to exclude a total of 21 due to different reasons. First of all, 6 of them stated that they had not seriously answered the questions in the study. In addition, there were 11 participants who showed an unusual response pattern (RSI (relative speed index) time > 2). Data sets with a value in the range of RSI-Time 2 and above should be viewed critically as their response pattern is considered “too fast, too straight, too weird” (Leiner, 2019). Afterwards, we checked for univariate outliers via Box-Whisker plots and for multivariate outliers via Mahalanobis Distance (p < 0.001). We did not exclude univariate outliers, but only three data sets that were considered extreme values. Furthermore, we excluded one multivariate outlier from the analysis. Our final sample consisted of n = 249 participants. Our participants were mainly young adults (M = 22.93, SD = 3.94), identified with female gender (nfemale = 194 (78%), nmale = 46 (19%), ndiverse = 6 (2%), nother = 3 (1%)) and were currently in the fourth semester (M = 4.08, SD = 3.06). There were no differences between the experimental groups regarding gender, age (F (3, 245) = 1.20, p = 0.31), study semester (F (2, 226) = 0.51, p = 0.68), academic self-concept (F (3, 245) = 0.21, p = 0.89), or NCC (F (3, 245) = 0.32, p = 0.81).

Manipulation check

To ensure that the experimental groups differed in perceived valence and controllability, we conducted two manipulation checks. First, we compared positive valence and negative valence groups. We found the intended significant difference between both groups (T (247) = − 24.94, p < 0.001). Participants with negative feedback reported significantly less positive valence compared with participants with positive expectation violations (Mnegative = 2.49, SDnegative = 0.96 vs. Mpositive = 5.74, SDpositive = 1.09). We conclude that the manipulation of valence was successful, more information on the manipulation can be found in the supplementary online.

Second, we compared high controllability and low controllability groups. We found the intended significant difference between both groups (T (247) = − 10.60, p < 0.001). Participants with less controllable expectation violations reported significantly less perceived controllability compared with participants with higher controllable expectation violations (Mlow = 4.00, SDlow = 1.36 vs. Mhigh = 5.67, SDhigh = 1.11). Also, participants differed in perceived controllability in all four case vignettes (exam grade, F (1, 247) = 38.36, p < 0.001; job interview, F (1, 247) = 48.72, p < 0.001; lecture, F (1, 247) = 39.15, p < 0.001; written assignment, F (1, 247) = 43.93, p < 0.001), always reporting significantly higher perceived controllability in the high controllability group compared with the low controllability group. Therefore, we conclude that the manipulation of controllability was successful, although mean differences are smaller compared with the manipulation of valence.

MANCOVA — main effects

We evaluated the main effects of our predictors valence and controllability as well as of our covariate NCC on accommodation, assimilation, and immunization. Valence was a significant predictor in the total model (Wilk’s Λ = 0.91, F (3, 239) = 8.13, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.09). Valence significantly predicted all three coping strategies with accommodation (F (1, 241) = 6.87, p = 0.009, ηp2 = 0.03), assimilation (F (1, 241) = 4.30, p = 0.04, ηp2 = 0.02), and immunization (F (1, 241) = 18.09, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.07). Interestingly, the participants in the negative valence group reported higher levels of all three coping strategies (accommodation, Mneg = 4.62, SDneg = 1.09 vs. Mpos = 4.38, SDpos = 1.04; assimilation, Mneg = 5.06, SDneg = 1.03 vs. Mpos = 4.35, SDpos = 0.98; immunization, Mneg = 4.03, SDneg = 0.98 vs. Mpos = 3.65, SDpos = 1.21) compared with positive valence. We could therefore confirm hypothesis 1 that negative valence leads to stronger assimilation, whereas we did not hypothesize the findings on stronger accommodation and immunization. Controllability was also a significant predictor in the total model (Wilk’s Λ = 0.95, F (3, 239) = 4.38, p = 0.005, ηp2 = 0.05). Controllability significantly predicted all three coping strategies with accommodation (F (1, 241) = 7.67, p = 0.006, ηp2 = 0.03), assimilation (F (1, 241) = 4.02, p = 0.046, ηp2 = 0.02), and immunization (F (1, 241) = 5.41, p = 0.021, ηp2 = 0.02). With higher controllability, participants reported stronger accommodation (Mlow = 4.47, SDlow = 1.04 vs. Mhigh = 4.53, SDhigh = 1.11) and assimilation (Mlow = 4.48, SDlow = 0.95 vs. Mhigh = 4.94, SDhigh = 1.13 but less immunization (Mlow = 4.17, SDlow = 0.99 vs. Mhigh = 3.47, SDhigh = 1.13) compared with lower controllability. Our finding that individuals report less immunization in a controllable situation confirms hypothesis 2. Also, the covariate NCC was a significant predictor in the total model (Wilk’s Λ = 0.95, F (3, 239) = 3.98, p = 0.009, ηp2 = 0.05). Higher NCC significantly predicted stronger assimilation (F (1, 241) = 4.18, p = 0.042, ηp2 = 0.02) and stronger immunization (F (1, 241) = 5.301, p = 0.022, ηp2 = 0.02) but was not a significant predictor of accommodation (F (1, 241) = 0.342, p = 0.559, ηp2 = 0.00). These effects only partly confirmed hypothesis 7 because we expected higher NCC to result in stronger assimilation (confirmed) and stronger accommodation (not confirmed). All correlations can be found in the supplementary material (Appendix B).

MANCOVA — interaction effects

We evaluated interaction effects between valence and controllability, between controllability and NCC, and between valence and self-enhancement. The interaction effect of valence and controllability was a significant predictor in the total model (Wilk’s Λ = 0.95, F (3, 239) = 4.53, p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.05) and predicted assimilation (F (1, 241) = 11.64, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.05), but neither accommodation (F (1, 241) = 0.01, p = 0.919, ηp2 = 0.00) nor immunization (F (1, 241) = 0.36, p = 0.547, ηp2 = 0.00). Therefore, we could not confirm hypothesis 4 that negative valence and low controllability result in stronger immunization, and only partly hypothesis 3 assuming that negative valence and high controllability lead to stronger assimilation (confirmed) and accommodation (not confirmed). Participants reported stronger assimilation after experiencing a negative controllable expectation violation compared with a positive controllable expectation violation (see Fig. 2).

The interaction effect of valence and self-enhancement was a significant predictor in the total model (Wilk’s Λ = 0.87, F (3, 239) = 5.81, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.07) and predicted accommodation (F (2, 241) = 5.04, p = 0.01, ηp2 = 0.04) and immunization (F (2, 241) = 12.75, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.10) but not assimilation (F (2, 241) = 1.99, p = 0.14, ηp2 = 0.02). Because of the descriptively small difference in reported accommodation, we performed a simple slope analysis, which confirmed the significance of positive valence with higher self-enhancement on accommodation compared with negative valence (T (494) = 2.88, p = 0.01, d = 0.26). After receiving unexpected positive feedback, participants reported stronger accommodation with higher self-enhancement compared with lower self-enhancement. Participants did not differ in accommodation to unexpected negative feedback, regardless of the extent of reported self-enhancement.

After receiving unexpected positive feedback, participants also reported less immunization with higher self-enhancement compared with lower self-enhancement, and after receiving unexpected negative feedback, participants reported stronger immunization with higher self-enhancement compared with lower self-enhancement (see Fig. 3). These results are in line with our hypotheses 5 and 6, assuming that with positive valence and higher self-enhancement, individuals report stronger accommodation and with negative valence and higher self-enhancement, stronger immunization.

The interaction effect of controllability and NCC was also a significant predictor in the total model (Wilk’s Λ = 0.96, F (3, 239) = 2.97, p = 0.033, ηp2 = 0.04) and predicted accommodation (F (1, 241) = 7.45, p = 0.007, ηp2 = 0.03) but neither assimilation (F (1, 241) = 1.75, p = 0.187, ηp2 = 0.01) nor immunization (F (1, 241) = 1.87, p = 0.173, ηp2 = 0.01). Participants with higher NCC reported stronger accommodation after experiencing an uncontrollable expectation violation compared with lower NCC. Contrary, participants with higher NCC reported less accommodation after experiencing a controllable expectation violation compared with lower NCC. Therefore, individuals with lower NCC accommodated more strongly in a controllable situation, whereas individuals with higher NCC accommodated more strongly in an uncontrollable situation (see Fig. 4). We explored this interaction effect without stating a direct hypothesis.

Discussion

Adaptive coping with unexpected successes and failures is crucial for a promising academic career (Skinner et al., 2013; Skinner & Saxton, 2019). In our study, we examined coping with expectation violations in the educational context using case vignettes. The aim was to better understand the mechanisms behind the asymmetrical coping with unexpected positive vs. negative feedback and the context-dependent effects of NCC on coping. For stronger accommodation and less immunization after unexpected positive feedback, our study identified stronger self-enhancement as a promoting condition. For stronger assimilation after unexpected negative feedback, our study identified higher controllability of the expectation violation as a promoting condition. NCC predicted stronger expectation maintenance, but in uncontrollable situations, individuals with higher NCC reported stronger accommodation.

Is there an optimism bias in coping with violated academic expectations?

The optimism bias states that after positive feedback, individuals report stronger expectation update, whereas after negative feedback, individuals report stronger expectation maintenance (e.g., Sharot, 2011). In the educational context, previous studies confirmed stronger expectation maintenance after receiving unexpected negative feedback (Henss & Pinquart, 2022, 2023). Unexpected positive feedback, on the other hand, was not related to stronger expectation update (Henss & Pinquart, 2022, 2023; Hobbs et al., 2022). Our results supported the assumption that expectations tend to persist after receiving unexpected negative feedback. Students reported stronger expectation maintenance with stronger assimilation and immunization after unexpected negative feedback. Stronger immunization indicates that individuals tend to devalue or deny the expectation violation, for example by considering the unexpected negative grade to be an exception. Stronger assimilation indicates that after an unexpected negative grade, individuals adjust their behavior to reduce the likelihood of a renewed expectation violation in the future, for example through higher learning effort.

Furthermore, unexpected negative feedback led to stronger assimilation in highly controllable situations. Practically, this means that if a grade is unexpectedly negative because the student was underprepared for the exam (internal cause), students are more likely to adjust their learning behavior next time to decrease the possibility of another expectation violation. Higher controllability was also associated with less immunization, presumably because students cannot easily devalue or deny an expectation violation resulting from internal causes such as effort.

Again, unexpected positive feedback was not significantly related to stronger accommodation. Contrary, unexpected negative feedback resulted in stronger accommodation compared with unexpected positive feedback, indicating a stronger need to cope with negative feedback. Only with stronger self-enhancement, we found the assumed effect that individuals reported stronger accommodation and less immunization after unexpected positive feedback. Thus, individuals may need to process and internalize positive feedback to actually update their expectations. The tendency to hold overly optimistic educational expectations (Carolan, 2017; Hacker et al., 2000; Pinquart & Pietzsch, 2022; Reynolds & Baird, 2010) may limit the potential for upward adjustments and therefore require self-enhancement as a promoting condition, or individuals might simply not have a stronger tendency for upward adjustments.

Our first research question, whether there is also an optimism bias in the educational context, can thus be answered as follows: partly, but the optimism bias depends on situational and dispositional characteristics.

Does higher NCC lead to context-dependent differences in coping?

NCC implies a preference for clear and unambiguous situations and a stronger aversion to uncertainty (Kossowska et al., 2019). This preference has so far led to the somewhat controversial result that individuals reported both more accommodation and assimilation after an expectation violation (Henss & Pinquart, 2022, 2023). This is presumably a combined strategy that relates in large part to the avoidance of future disappointment through an adjustment of behavior in order to meet prior expectations in the future in the event of a previously lower grade, and an adjustment of expectation in order not to fail the expectation again in the future.

In our current study, we found that NCC was only related to stronger expectation maintenance (assimilation and immunization) but not to stronger accommodation. Although this result is in line with previous assumptions from other studies (e.g., Dijksterhuis et al., 1996), it contradicts our prior results on how individuals with higher NCC cope with expectation violations (Henss & Pinquart, 2022, 2023). Higher NCC only led to stronger expectation update (accommodation) when the expectation violation was low in controllability, underlining the assumption that the effects of NCC are highly context-dependent (Kemmelmeier, 2015). Context dependence might also explain why our results differ from previous ones: in both previously conducted studies, participants received direct feedback on a task that they otherwise do not often or never work on. In this study, the situations described were familiar to them and related more strongly to the educational context. In sum, higher NCC is associated with expectation maintenance in our study. However, higher NCC can also lead to stronger accommodation and thus expectation update in an uncontrollable situation. Consequently, the effects of higher NCC are dependent on the context of expectation violation.

Theoretical implications

In summary, several theoretical implications can be drawn from our results. First of all, our study contributed to the assumption that educational expectations tend to be highly stable and certain (e.g., Carolan, 2017; Domina et al., 2011). Our results identified cognitive biases such as self-enhancement as underlying mechanisms of expectation persistence after unexpected negative feedback: additionally, to individuals reporting stronger assimilation and immunization, individuals with stronger self-enhancement also reported stronger immunization.

The extent to which individuals adapt and process feedback that exceeds their initial expectations appears to be less significant compared to situations involving healthy participants in clinical or learning settings (Kube & Glombiewski, 2021; Kuzmanovic & Rigoux, 2017), because unexpected positive feedback led to less accommodation, and only with strong self-enhancement tendencies, individuals reported stronger accommodation after unexpected positive feedback according to the optimism bias. Furthermore, we contributed to the assumption that the effects of NCC are highly context-dependent. Whereas we found a coping pattern of accommodation and assimilation in our previous studies for less elaborated expectations (Henss & Pinquart, 2022, 2023), we found stronger expectation maintenance in this study for more strongly elaborated expectations, indicating that although NCC is highly context-dependent, several conclusions and regularities can be drawn from its effects.

Practical implications

Holding positive educational expectations was associated with a variety of positive achievement and health outcomes in previous studies (Domina et al., 2011; Rasmussen et al., 2006). With unexpected positive feedback, self-enhancement emerged as a supporting condition for stronger accommodation. In a longitudinal study, self-enhancement also proved to be an adaptive influence and led to higher well-being (Dufner et al., 2015), and optimistic expectations are likely to motivate students to strive for higher achievement goals (Ruthig et al., 2007). Therefore, supporting stronger self-enhancement tendencies may be especially beneficial for individuals with anxiety or negative educational expectations.

To support self-enhancement tendencies, creating situations with higher controllability can be conducive. Previous results indicate that higher controllability leads to less stress and depression (Ruthig et al., 2009), positive academic outcomes (Ruthig et al., 2007) and fewer drop-outs during the course of study (Respondek et al., 2017). Our results support these assumptions, and many of our findings point to adaptive coping behaviors when controllability is high: higher controllability led to stronger accommodation and assimilation, but less immunization, indicating that only external causes of success or failure result in reluctance to process the unexpected feedback, whereas internal causes support behavioral changes as well as expectation changes. In practice, higher controllability can be supported with transparency of requirements and evaluation criteria, feedback referring to controllable aspects of achievement, inclusion of suggestions for improvement, and avoidance of ambiguity in exams or assignments. Both positive and negative feedback should be reported constructively and promptly, and expectations for students should be clearly articulated (see also Respondek et al., 2017).

This could promote self-enhancement and therefore contribute to positive educational expectations (e.g., because unexpected positive feedback can be clearly attributed to own abilities or effort), and higher controllability might especially help individuals with higher NCC to reduce uncertainty. For higher controllability, we found stronger expectation maintenance for individuals with higher NCC. But for lower controllability, they were more likely to update their expectations than individuals with lower NCC. There are different conclusions regarding the adaptivity of stronger accommodation for individuals with higher NCC in uncontrollable situations that point to the need for further research. First, it is important to consider that for individuals with high NCC, uncertainties and discrepancies are particularly unpleasant, and coping is particularly adaptive for them if it resolves this aversive state as quickly as possible (e.g. Schrackmann & Oswald, 2014). In an uncontrollable situation, it is decisive to consider whether similar expectation violations are likely to occur in the future (e.g., same instructor on the next exam) or whether this would be rather unlikely (e.g., different instructor on the next exam). In the former case, accommodation would be the adaptive strategy to eliminate uncertainty and dissonance as quickly as possible and simultaneously reduce the likelihood of future expectation violations. In the second case, accommodation would be a maladaptive strategy because, although uncertainty and dissonance would be eliminated in the near term, future expectation violations and thus aversive situations would be more likely.

Limitations and future directions

In our study, we used case vignettes to test scenarios that were as close to academic reality as possible in a standardized, experimental context. This has already been successfully applied in other studies on the manipulation of expectation violations (Gesualdo & Pinquart, 2022; Kube et al., 2022). Nevertheless, we induced hypothetical expectation violations and the results may not be fully transferable to real expectation violations. A stronger real-life focus would require studies conducted in educational contexts in cohorts before and after exam periods to examine how students cope with expectation-violating outcomes. However, this approach is not readily feasible and entails less standardization.

Manipulating controllability posed a difficulty in our study. Much theoretical and experimental work indicates that subjectively perceived controllability may differ from objective controllability (for review, see Robinson & Lachman, 2017). Our experimental groups differed significantly in perceived controllability, yet the low controllability group had a mean score in the middle range of the scale with single outliers to the top.

However, the important starting point for future research should be to directly capture the adaptivity of coping behavior. Here, special attention should be paid to the effects of higher NCC and it should be directly determined whether the strategies applied to prevent expectation violations in the future.

Conclusion

Students often experience expectation violations in the course of their educational pathway and need to adaptively cope with them for a successful academic career. Coping according to the optimism bias can be beneficial and lead to positive, motivating expectations after successes and persistent positive expectations despite failures. Our study supports these findings and also shows that certain conditions must be met for students to cope adaptively. High controllability has an adaptive effect on coping with unexpected negative feedback, and high self-enhancement promotes the integration of unexpected positive achievement into future educational expectations. Students with high NCC exhibit potentially maladaptive tendencies because their need for rapid resolution of uncertainty may promote future expectation violations inducing aversive uncertainty again.

References

Arens, A. K., Jansen, M., Preckel, F., Schmidt, I., & Brunner, M. (2021). The structure of academic self-concept: A methodological review and empirical illustration of central models. Review of Educational Research, 91(1), 34–72. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654320972186

Caprar, D. V., Do, B., Rynes, S. L., & Bartunek, J. M. (2016). It’s personal: An exploration of students’ (non) acceptance of management research. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 15(2), 207–231. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2014.0193

Carolan, B. V. (2017). Assessing the adaptation of adolescents’ educational expectations: Variations by gender. Social Psychology of Education, 20(2), 237–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-017-9377-y

Dijksterhuis, A., Van Knippenberg, A., Kruglanski, A. W., & Schaper, C. (1996). Motivated social cognition: Need for closure effects on memory and judgment. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 32(3), 254–270. https://doi.org/10.1006/jesp.1996.0012

Domina, T., Conley, A., & Farkas, G. (2011). The link between educational expectations and effort in the college-for-all era. Sociology of Education, 84(2), 93–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941406411401808

Dufner, M., Reitz, A. K., & Zander, L. (2015). Antecedents, consequences, and mechanisms: On the longitudinal interplay between academic self-enhancement and psychological adjustment. Journal of Personality, 83(5), 511–522. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12128

Garrett, N., & Sharot, T. (2017). Optimistic update bias holds firm: Three tests of robustness following Shah et al. Consciousness and Cognition, 50, 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2016.10.013

Gerdes, H., & Mallinckrodt, B. (1994). Emotional, social, and academic adjustment of college students: A longitudinal study of retention. Journal of Counseling & Development, 72(3), 281–288. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1994.tb00935.x

Gesualdo, C., & Pinquart, M. (2022). Predictors of coping with health-related expectation violations among University students. American Journal of Health Behavior, 46(4), 488–496. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.46.4.9

Goossens, L. (2001). Global versus domain-specific statuses in identity research: A comparison of two self-report measures. Journal of Adolescence, 24(6), 681–699. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.2001.0438

Green, J. D., Pinter, B., & Sedikides, C. (2005). Mnemic neglect and self-threat: Trait modifiability moderates self-protection. European Journal of Social Psychology, 35(2), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.242

Gollwitzer, M., Thorwart, A., & Meissner, K. (2018). Psychological responses to violations of expectations. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2357. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02357

Gonçalves, T., Lemos, M. S., & Canário, C. (2019). Adaptation and validation of a measure of students’ adaptive and maladaptive ways of coping with academic problems. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 37(6), 782–796. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282918799389

Hacker, D. J., Bol, L., Horgan, D. D., & Rakow, E. A. (2000). Test prediction and performance in a classroom context. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(1), 160. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.92.1.160

Hay, I., Ashman, A. F., van Kraayenoord, C. E., & Stewart, A. L. (1999). Identification of self verification in the formation of children’s academic self-concept. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(2), 225. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.91.2.225

Henss, L., & Pinquart, M. (2022). Dispositional and situational predictors of coping with violated achievement expectations. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 75(6), 1121–1134. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747021821104810

Henss, L., & Pinquart, M. (2023). Expectations do not need to be accurate to be maintained: Valence and need for cognitive closure predict expectation update vs. persistence. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1127328. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1127328

Hepper, E. G., Gramzow, R. H., & Sedikides, C. (2010). Individual differences in self enhancement and self-protection strategies: An integrative analysis. Journal of Personality, 78(2), 781–814. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00633.x

Hepper, E. G., Sedikides, C., & Cai, H. (2013). Self-enhancement and self-protection strategies in China: Cultural expressions of a fundamental human motive. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44(1), 5–23. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1177/0022022111428515

Hobbs, C., Vozarova, P., Sabharwal, A., Shah, P., & Button, K. (2022). Is depression associated with reduced optimistic belief updating? Royal Society Open Science, 9(2), 190814. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.190814

Jansen, L. A. (2016). The optimistic bias and illusions of control in clinical research. IRB, 38(2), 8–14. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26776034

Kemmelmeier, M. (2015). The closed-mindedness that wasn’t: Need for structure and expectancy-inconsistent information. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 896. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00896

Kossowska, M., Orehek, E., & Kruglanski, A. W. (2010). Motivation towards closure and cognitive resources: An individual differences approach. Handbook of Individual Differences in Cognition: Attention, Memory, and Executive Control, 369–382. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1210-7_22

Kossowska, M., Szwed, P., & Wyczesany, M. (2019). Motivational effects on brain activity: Need for closure moderates the impact of task uncertainty on engagement-related P3b. NeuroReport, 30(17), 1179–1183. https://doi.org/10.1097/wnr.0000000000001334

Krieg, D. (2013). High expectations for higher education? Perceptions of college and experiences of stress prior to and through the college career. College Student Journal, 47(4), 635–643.

Kube, T., & Glombiewski, J. A. (2021). How depressive symptoms hinder positive information processing: An experimental study on the interplay of cognitive immunisation and negative mood in the context of expectation adjustment. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 45, 517–528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-020-10191-4

Kube, T., Kirchner, L., Rief, W., Gärtner, T., & Glombiewski, J. A. (2019). Belief updating in depression is not related to increased sensitivity to unexpectedly negative information. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 123, 103509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2019.103509

Kube, T., Kirchner, L., Lemmer, G., & Glombiewski, J. A. (2022). How the discrepancy between prior expectations and new information influences expectation updating in depression—The greater, the better? Clinical Psychological Science, 10(3), 430–449. https://doi.org/10.1177/21677026211024644

Kuzmanovic, B., & Rigoux, L. (2017). Valence-dependent belief updating: Computational validation. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1087. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01087

Lefebvre, G., Lebreton, M., Meyniel, F., Bourgeois-Gironde, S., & Palminteri, S. (2017). Behavioural and neural characterization of optimistic reinforcement learning. Nature Human Behaviour, 1(4), 0067. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0067

Leiner, D. J. (2019). Too fast, too straight, too weird: Non-reactive indicators for meaningless data in internet surveys. Survey Research Methods, 13, 229–248. https://doi.org/10.18148/srm/2019.v13i3.7403

Mendes, W. B., Blascovich, J., Hunter, S. B., Lickel, B., & Jost, J. T. (2007). Threatened by the unexpected: Physiological responses during social interactions with expectancy violating partners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(4), 698. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.4.698

Neuberg, S. L., & Newsom, J. T. (1993). Personal need for structure: Individual differences in the desire for simpler structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(1), 113–131. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.65.1.113

Panitz, C., Endres, D., Buchholz, M., Khosrowtaj, Z., Sperl, M. F., Mueller, E. M., Schubö, A., Schütz, A. C., Teige-Mocigemba, S., & Pinquart, M. (2021). A revised framework for the investigation of expectation update versus maintenance in the context of expectation violations: The ViolEx 2.0 model. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 726432. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.726432

Pinquart, M., & Block, H. (2020). Coping with broken achievement-related expectations in students from elementary school: An experimental study. International Journal of Developmental Science, 14(1–2), 9–17. https://doi.org/10.3233/dev-200001

Pinquart, M., & Ebeling, M. (2020). Parental educational expectations and academic achievement in children and adolescents—A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 32, 463–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09506-z

Pinquart, M., & Pietzsch, M. C. (2022). Change in students’ educational expectations–a meta-analysis. Journal of Educational and Developmental Psychology, 12, 43. https://doi.org/10.5539/jedp.v12n1p43

Rasmussen, H. N., Wrosch, C., Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (2006). Self-regulation processes and health: The importance of optimism and goal adjustment. Journal of Personality, 74(6), 1721–1748. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00426.x

Respondek, L., Seufert, T., Stupnisky, R., & Nett, U. E. (2017). Perceived academic control and academic emotions predict undergraduate university student success: Examining effects on dropout intention and achievement. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 243. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00243

Reynolds, J. R., & Baird, C. L. (2010). Is there a downside to shooting for the stars? Unrealized educational expectations and symptoms of depression. American Sociological Review, 75(1), 151–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122409357064

Rief, W., Glombiewski, J. A., Gollwitzer, M., Schubö, A., Schwarting, R., & Thorwart, A. (2015). Expectancies as core features of mental disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 28(5), 378–385. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000184

Robinson, S. A., & Lachman, M. E. (2017). Perceived control and aging: A mini-review and directions for future research. Gerontology, 63(5), 435–442. https://doi.org/10.1159/000468540

Roets, A., & Van Hiel, A. (2011). Allport’s prejudiced personality today: Need for closure as the motivated cognitive basis of prejudice. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(6), 349–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721411424894

Ruthig, J. C., Haynes, T. L., Perry, R. P., & Chipperfield, J. G. (2007). Academic optimistic bias: Implications for college student performance and well-being. Social Psychology of Education, 10, 115–137. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1007/s11218-006-9002-y

Ruthig, J. C., Haynes, T. L., Stupnisky, R. H., & Perry, R. P. (2009). Perceived academic control: Mediating the effects of optimism and social support on college students’ psychological health. Social Psychology of Education, 12, 233–249. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11218-008-9079-6

Schlink, S., & Walther, E. (2007). Kurz und gut: Eine deutsche Kurzskala zur Erfassung des Bedürfnisses nach kognitiver Geschlossenheit. [Short and sweet: A German short scale to assess the need for cognitive closure]. Zeitschrift für Sozialpsychologie, 38(3), 153–161. https://doi.org/10.1024/0044-3514.38.3.153

Schoon, I., & Ng-Knight, T. (2017). Co-development of educational expectations and effort: Their antecedents and role as predictors of academic success. Research in Human Development, 14(2), 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427609.2017.1305808

Schrackmann, M., & Oswald, M. E. (2014). How preliminary are preliminary decisions. Swiss J. Psychol., 73, 5–11. https://doi.org/10.1024/1421-0185/A000122

Shanahan, M. L., Fischer, I. C., & Rand, K. L. (2020). Hope, optimism, and affect as predictors and consequences of expectancies: The potential moderating roles of perceived control and success. Journal of Research in Personality, 84, 103903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2019.103903

Sharot, T. (2011). The optimism bias. Current Biology, 21(23), R941–R945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2011.10.030

Skinner, E. A., & Saxton, E. A. (2019). The development of academic coping in children and youth: A comprehensive review and critique. Developmental Review, 53, 100870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2019.100870

Skinner, E., Pitzer, J., & Steele, J. (2013). Coping as part of motivational resilience in school: A multidimensional measure of families, allocations, and profiles of academic coping. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 73(5), 803–835. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164413485241

Smith, J. S., & Wertlieb, E. C. (2005). Do first-year college students’ expectations align with their first-year experiences? NASPA Journal, 42(2), 153–174. https://doi.org/10.2202/1949-6605.1470

Strelow, A. E., Dort, M., Schwinger, M., & Christiansen, H. (2020). Influences on pre-service teachers’ intention to use classroom management strategies for students with ADHD: A model analysis. International Journal of Educational Research, 103, 101627.

Strojny, P., Kossowska, M., & Strojny, A. (2016). Search for expectancy-inconsistent information reduces uncertainty better: The role of cognitive capacity. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 395. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00395

Thompson, A. (2015). Coping with stress in undergraduate university students: Development and validation of the coping inventory for academic striving (CIAS) to examine key educational outcomes in correlational and experimental studies (Doctoral dissertation). Université d'Ottawa/University of Ottawa. https://doi.org/10.20381/ruor-4763

van Doeselaar, L., Becht, A. I., Klimstra, T. A., & Meeus, W. H. (2018). A review and integration of three key components of identity development. European Psychologist. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000334

Webster, D. M., & Kruglanski, A. W. (1994). Individual differences in need for cognitive closure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(6), 1049. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1049

Webster, D. M., & Kruglanski, A. W. (1997). Cognitive and social consequences of the need for cognitive closure. European Review of Social Psychology, 8(1), 133–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779643000100

Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92(4), 548–573. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.92.4.548

Weiner, B. (2000). Intrapersonal and interpersonal theories of motivation from an attributional perspective. Educational Psychology Review, 12, 1–14.

Zeidner, M. (1995). Adaptive coping with test situations: A review of the literature. Educational Psychologist, 30(3), 123–133. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3003_3

Zhang, J., Miao, D., Sun, Y., Xiao, R., Ren, L., Xiao, W., & Peng, J. (2014). The impacts of attributional styles and dispositional optimism on subject well-being: A structural equation modelling analysis. Social Indicators Research, 119, 757–769.

Zimmerman, B., & Schunk, D. (2006). Competence and control beliefs: Distinguishing the means and ends. Handbook of Educational Psychology, 2, 349–367.

Zingoni, M., & Byron, K. (2017). How beliefs about the self influence perceptions of negative feedback and subsequent effort and learning. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 139, 50–62. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1016/j.obhdp.2017.01.007

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) — project number 290878970-GRK 2271, project 7. There was no further involvement of the funding source. Data and study materials are available on Open Science Framework (osf.io/2xkms/).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Current themes of research:

Expectation violation. Coping with overly optimistic educational expectation. Parental expectations. Effects of parenting behavior and parenting styles. Development of children and adolescents with behavioral or mental disorders.

Most relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education:

Henss, L., & Pinquart, M. (2023). Expectations do not need to be accurate to be maintained: Valence and need for cognitive closure predict expectation update vs. persistence. Frontiers in Psychology, 14.

Henss, L., & Pinquart, M. (2022). Dispositional and situational predictors of coping with violated achievement expectations. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 75(6), 1121-1134.

Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2003). Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: A meta-analysis. Psychology and aging, 18(2), 250.

Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2006). Helping caregivers of persons with dementia: Which interventions work and how large are their effects?. International psychogeriatrics, 18(4), 577-595.

Pinquart, M. (2017). Associations of parenting dimensions and styles with externalizing problems of children and adolescents: An updated meta-analysis. Developmental psychology, 53(5), 873.

Pinquart, M., & Gerke, D. C. (2019). Associations of parenting styles with self-esteem in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 2017-2035.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Henss, L., Pinquart, M. Coping with expectation violations in education: the role of optimism bias and need for cognitive closure. Eur J Psychol Educ (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-023-00783-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-023-00783-5