Abstract

Class teachers have a meaningful role in the life of primary school students as they are responsible for the majority of their students’ instruction. Previous research has shown that teachers who make efforts to learn and develop in their work also promote their students’ learning and well-being. This learning orientation is referred to in this study as teachers’ professional agency. The well-being of students has been shown to be challenged in many ways already in primary school. However, we need more research on how primary school students experience well-being in classrooms in relation to their studies and whether their class teacher’s professional agency relates to their well-being. We examined students’ study well-being from two perspectives: study engagement and study burnout. Multilevel structural equation modelling was applied in the analysis to explore perceived study well-being in the classroom (student and class level) and its relation to class teachers’ sense of professional agency. The results indicate that a high level of study burnout at the class level decreases students’ study well-being over time and also challenges class teachers’ sense of professional agency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Students’ well-being in school has become an increasing concern among educational experts. Younger and younger students, already in primary school, experience exhaustion, fatigue, and cynicism towards school (Choi, 2018; FIHW, 2021; Raniti et al., 2017; Salmela-Aro et al., 2016). Similarly, students’ sense of study engagement has been found to begin to decline after the first grades of primary school (Blumenfeld et al., 2005; Luo et al., 2009) and especially after the transition to secondary school (Kiuru et al., 2020; Ulmanen et al., 2022). Study engagement has been shown to be negatively correlated with study burnout among primary school students (af Ursin et al., 2021; Salmela-Aro et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2022). Moreover, high study engagement and burnout can also occur at the same time (Tuominen-Soini & Salmela-Aro, 2014) implying that students who are dedicated and enjoy learning can be simultaneously exhausted and overwhelmed by the workload. However, these phenomena have been studied more often in secondary and high school students (e.g. Kiuru et al., 2020; Salmela-Aro & Read, 2017; Salmela-Aro & Upadyaya, 2014), and we need more longitudinal research on how younger students experience study well-being in primary school, especially collectively in student groups. We aim to respond to this research gap by studying the construction of study well-being (i.e. study engagement and study burnout) in primary school with a longitudinal and multilevel research design that enables more detailed insight into how individual students and class groups’ collective experience of study well-being develop during one year.

Decreasing study engagement has been suggested to be tackled by investing in social relationships, especially the support that the teacher gives to the students (af Ursin et al., 2021). In Finland, the class teacher plays a significant role in the primary school student’s life as they are often responsible for almost all of the student’s instruction over several years. Positive and affective teacher-student relationships have been associated with better learning outcomes as well as better adjustment and a sense of belonging in school (e.g. Corbin et al., 2019; Hajovsky et al., 2020). In addition, it has been shown that teachers who pursue professional learning and see the potential in every student tend to succeed in facilitating their students’ learning and well-being (Darling-Hammond, 2008; Darling-Hammond et al., 2022; Rissanen et al., 2021). A teacher who is ready to learn is also likely to respond sensitively to the needs of their students and the changing situations in the class. In our previous research, this kind of learning orientation towards the teacher’s teaching work, i.e. professional agency in the classroom, has been related to stronger school engagement, more affective teacher-student interaction and learning (e.g. Palmgren et al., 2017; Saariaho et al., 2019; Soini et al., 2014). Teacher’s professional agency is an integrative concept that describes the teacher’s motivation, self-efficacy, and strategies for learning at work (Pietarinen et al., 2016; Pyhältö et al., 2012; Soini et al., 2016). In other words, a teacher who has a strong sense of professional agency is willing and has the efficacy and skills to develop, transform, and reflect on teaching and learning environments by themselves and together with students. Our previous research has shown positive relationships between agency, well-being, and learning, and thus we suggest that class teachers’ sense of professional agency in the classroom is also positively related to students’ and class groups’ study engagement and negatively related with study burnout.

Two perspectives on student well-being: study engagement and study burnout

Student well-being is a growing research field and has been studied from various perspectives, mainly among secondary and higher education students (e.g. Ouweneel et al., 2011; Salmela-Aro & Read, 2017; Tuominen-Soini & Salmela-Aro, 2014), and it has been recognized that well-being is a subjective experience that forms in a complex, interactive process of different experiences, predispositions and values that are influenced by personal and environmental factors. Previously, educational psychological well-being research has focused mainly on the subjective aspect of the individual, but, in recent years, the focus has shifted to the study of communities, such as classes and schools (Roffey, 2015).

International comparisons show that more and more Finnish students are not thriving in school (Choi, 2018), youth sleep problems and fatigue have increased (Raniti et al., 2017), and students are more cynical towards school (Salmela-Aro et al., 2016). These results have caused growing concern about the well-being of students. The latest school health surveys (FIHW, 2021) show that students’ overall satisfaction with their lives and experience of belonging to school and class communities are declining. It seems that the well-being experienced by students begins to degrade especially when moving from primary to secondary school (Kiuru et al., 2020; Ulmanen et al., 2022).

Student well-being is also strongly associated with psychological and social well-being, as school forms a key part of students’ daily lives (Eccles & Roeser, 2011; Li & Lerner, 2011; Salmela-Aro & Upadyaya, 2012; Tuominen-Soini & Salmela-Aro, 2014). Multiple concepts are used to describe schoolwork-related well-being, such as study well-being (e.g. Tikkanen et al., 2021; Ulmanen et al., 2022, 2023), academic well-being (e.g. Korhonen et al., 2014; Tuominen-Soini et al., 2012), student well-being (Roffey, 2015; Salmela-Aro et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2022), and school well-being (e.g. Kiuru et al., 2020; Maksniemi et al., 2018; Salmela-Aro, 2017; Salmela-Aro et al., 2019). In this study, we refer to study well-being as a student’s study-related experiences of well-being from two perspectives: study engagement and study burnout (Rautanen 2022; Salmela-Aro & Read, 2017; Tikkanen, 2021; Ulmanen 2022, 2023). We approach study engagement and study burnout as two connected but separate perspectives of study well-being that may also occur simultaneously and, thus, are not opposites of each other (Salmela-Aro & Read, 2017; Tuominen-Soini & Salmela-Aro, 2014; Ulmanen et al., 2022, 2023).

Study engagement refers to a positive and energetic attitude towards schooling and studying. A student who experiences strong study engagement is dedicated, full of energy, and easily absorbed in studying (Salmela-Aro & Upadyaya, 2012). The majority of primary school students have been shown to be engaged or moderately engaged in school (Yang et al., 2022). Girls typically report higher levels of study engagement compared to boys (Lam et al., 2012; Rautanen et al., 2022; Salmela-Aro & Upadyaya, 2012). Extensive research evidence shows that a socially supportive school environment and positive relationships strengthen students’ study engagement (Estell & Perdue, 2013; Kiefer et al., 2015; Konu et al., 2002; Løhre et al., 2010; Rautanen et al. 2022; Ulmanen et al., 2022, 2023; Weare & Gray, 2003; Zullig et al., 2010). In addition, it has been suggested that study engagement can become epidemic and spread across the school community (Havik & Westergård, 2020; Kiuru et al., 2009; Ouweneel et al., 2011; Tuominen-Soini & Salmela-Aro, 2014). However, study engagement has been found to decline gradually over the school years (Salmela-Aro et al., 2016; Wang & Eccles, 2012).

Study burnout refers to fatigue regarding schoolwork, cynical and negative attitudes towards schoolwork, and feelings of inadequacy as a student (Salmela-Aro et al., 2009; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004). School burnout can be seen as a condition caused by a conflict between the student’s own resources for schoolwork and the student’s own or others’ expectations of school performance (Kiuru et al., 2008; Salmela-Aro & Upadyaya, 2014). Sixth graders (ages 12–13) in Finland experience moderate levels of study exhaustion and boys experience more cynicism towards schoolwork than girls (Maksniemi et al., 2018). Motivation towards schoolwork and the social environment of the school have both been shown to be related to the development of school burnout (Salmela-Aro, 2017). In the worst scenario, school burnout has been found to lead to estrangement from school, as well as to an overall decrease in well-being and future study motivation (Tuominen-Soini & Salmela-Aro, 2014). School burnout has also been shown to be contagious among students (Cho et al., 2023; Kiuru et al., 2008; Salmela-Aro et al., 2017; Lindfors et al., 2018), burnout experienced in a group seems to increase its contagiousness, and burnout can spread to other student groups, teachers, or affect the whole school (Cho et al., 2023; Meredith et al., 2020; Oberle & Schonert-Reichl, 2016; Pietarinen et al., 2021). In addition, teacher exhaustion has been associated with increased cynicism towards schoolwork among primary school students (Tikkanen et al., 2021).

Although study engagement and study burnout have been studied comprehensively, previous research concerns particularly secondary and higher education and has focused mostly on the individual student’s perspective. In addition, the relation between teacher and student well-being has also been identified. However, further research is needed on how well-being is structured in the primary school class group. Furthermore, we aimed to find out what would promote study engagement and, on the other hand, tackle and prevent study burnout in primary school classes. The class teacher plays a key role in the primary school class and, based on our previous studies, we assume that the class teacher’s sense of professional agency could be an important asset in strengthening study well-being in the classroom.

Class teacher’s professional agency in the classroom

Finnish class teachers experience high professional agency and autonomy in their work (OECD, 2018; Yli-Pietilä et al., 2023a, 2023b). They perceive new learning and continuous development as important parts of their work and are able to modify their teaching and perceptions of teaching as the situation requires.

The concept of professional agency combines psychological and social perspectives of the teacher’s cognitive, motivational, and attitudinal resources for learning, as well as abilities to foster and manage new learning in teacher-student interaction (Toom et al., 2021). A teacher who experiences strong professional agency perceives learning as a fundamental part of their own work. The experience of agency is relational and can change depending on the situation and context (Pietarinen et al., 2016; Pyhältö et al., 2012; 2014; Soini et al., 2016; Toom et al., 2015).

Experiencing agency includes three factors that enable learning: motivation, efficacy, and strategies for learning (Pyhältö et al., 2012, 2014). Based on our empirical work teacher’s professional agency in the classroom manifests as the teacher’s readiness to modify and reform their own teaching both jointly with students and through individual reflection (Pietarinen et al., 2016; Soini et al., 2016). These modes of learning are operationalised in our work as a Collaborative learning environment and transformative practice and Reflection in the classroom. Our previous results show that teachers’ strong sense of professional agency is related to lower levels of burnout symptoms and the ability to regulate their own well-being at work (Soini et al., 2016; Yli-Pietilä et al., 2023a). On the other hand, some of our results suggest that teachers’ high tendency to reflect may also increase feelings of inadequacy in relation to teacher-student interaction or cynicism towards the work community (Heikonen et al., 2017; Soini et al. 2016; Yli-Pietilä et al., 2023b).

The experience of teacher’s professional agency seems to remain high over time with relatively little individual variation. In our previous study, we found four professional agency profiles of Finnish class teachers, which showed that the majority of teachers experienced high and stable agency (Yli-Pietilä et al., 2023a). Only a few percent of teachers experienced decreases or increases in their sense of professional agency over 2 years, even though the study was carried out during the implementation of the new curriculum (FNBE (Finnish National Board of Education), 2014), which challenged teachers to evolve their practices. Teachers who had a strong and stable professional agency profile experienced fewer burnout symptoms and had the best capabilities to utilise self-regulation and co-regulation strategies in regulating their well-being at work (Yli-Pietilä et al., 2023a). Our results also indicated that even a small decrease in sense of professional agency can increase teachers’ risk of burnout. But how is teachers’ sense of professional agency associated with students’ experience of study well-being?

What we can assume about the relation between teacher’s professional agency and study well-being

The quality of socio-pedagogical interaction between teacher and student has been found to be crucial for teachers’ and students’ learning and well-being (Graham et al., 2016; Pyhältö et al., 2010, 2015). Students who experience positive and supportive relationships with their teachers are more engaged in studying and have a lower risk of study burnout (Lindfors et al., 2018; Pietarinen et al., 2014). This kind of teacher-student interaction also strengthens teachers’ engagement and commitment to work (Soini et al., 2010; Taxer et al., 2019). In contrast, problems and conflicts in teacher-student interaction may increase the teacher’s risk of burnout (Corbin et al., 2019; Spilt et al., 2011) as well as student challenges regarding studying, well-being, and attitudes towards school (e.g. Deng et al., 2022; Milkie & Warner, 2011).

Having a strong sense of professional agency in the classroom requires a positive and close relationship with the students. A teacher who has strong professional agency sees collaboration with students as a fundamental part of teaching and learning and is able to create a supportive classroom climate and modify learning environments to be suitable for every student. The student’s relationship with the class teacher in primary school is likely to be one of the most important relationships with an adult during the student’s childhood. In Finnish primary schools, every class has their own class teacher that is responsible for the majority of the teaching in the class. This study includes only students who had the same class teacher from 4 to 5th grade (ages 10–12).

The association of teacher learning with students’ learning, engagement in school, and school success has also been identified in several studies (e.g. Darling-Hammond, 2008; Eccles & Roeser, 2011; Rissanen et al., 2021). When a teacher sees learning as an important part of their own work and is prepared to change the way they think and act, students are more excited about learning and are more likely to engage in school. In addition, teachers with high self-efficacy beliefs have been shown to have closer and stronger relationships and experience less conflicts with students (Hajovsky et al., 2020). Motivation, self-efficacy belief, and strategies for new learning are at the core of teacher’s professional agency (Pietarinen et al., 2016; Soini et al., 2016).

In addition, teacher support and teaching style have been shown to affect students’ well-being in school. Recent research indicates that primary school students experience higher and more stable social support for schoolwork from the teacher than in lower secondary school (Ulmanen, 2023). The results show that girls experience receiving more support from the teacher than boys at ages 10 to 12 years (Rautanen et al., 2022). Perceived social support from the teacher can also prevent study burnout (Tikkanen et al., 2021). Furthermore, the teacher’s personal characteristics and ways of structuring classroom situations have been associated with student well-being (Larsen et al., 2020). A student autonomy-supportive teaching style has been shown to promote study engagement among primary students, whereas an autonomy-suppressive teaching style seems to hinder it (Yang et al., 2022). However, the focus has recently shifted from antecedents and outcomes of engagement and burnout towards researching the social context and learning environment and their multifaceted relations with school engagement and burnout (Virtanen et al. 2018; Salmela-Aro & Upadyaya, 2020).

Although teacher and student learning and well-being seem to be interrelated in many ways, we still know very little about how primary school students’ (individual students’ and class groups’) experience of study well-being is related to their class teacher’s sense of professional agency.

Aim of the study

The aim of the study was to deepen our understanding of the construction of study well-being among primary school students and class groups, as well as its relation to class teachers’ sense of professional agency in the classroom. Hence, two research questions were formulated:

-

1.

How do students’ perceived study engagement and study burnout (i.e. study well-being) develop and relate to each other over time at the individual student and the class group level?

-

2.

How is the class teacher’s sense of professional agency related to perceived study engagement and study burnout in the class group (i.e. students’ collective study well-being)?

We examined the relation between study engagement and study burnout using a longitudinal and multilevel research design. In addition, we examined how gender and class size were related to experienced well-being in the classroom. Gender is a well-researched variable with engagement and burnout, whereas, primary school class group size has not been studied to the same extent. The first hypothesized model is presented in Fig. 1.

-

H1. Within-level (student): Study engagement and study burnout are distinct but related constructs. They predict themselves positively over time and each other negatively over time. Girls experience higher levels of study engagement and lower levels of study burnout.

-

H2. Between-level (class): Study engagement and study burnout are distinct but related constructs. They predict themselves positively over time and each other negatively over time.

Furthermore, we aimed to find out how class teachers’ sense of professional agency is related to the class group’s experience of study well-being. We tested both possible directions. The hypothesized models are presented in Figs. 2 and 3.

-

H3. Teacher’s strong sense of professional agency predicts higher study engagement and lower study burnout in the class (Fig. 2).

-

H4. High study engagement and low study burnout in the class predict teacher’s high sense of professional agency (Fig. 3).

Materials and methods

Research context

Finnish primary schools include the first 7 years of school. Students start preschool when they are 6 years old and move to lower secondary school in the year they turn 13. Every primary school class has their own class teacher who takes care of the majority of the teaching of the class, is in contact with the student’s guardians, and has the main responsibility for the teaching, but also guiding and well-being, of the student in the class.

Every class teacher has a master’s degree in education and is qualified to teach every subject that is taught in primary schools. Typically, class teachers teach their students for a relatively long time, usually from 1 to several years or even for the whole duration of primary school. Thus, the relationship with class teacher is very likely to be one of the student’s most important relationships with an adult during childhood.

Data collection and participants

The data of this study were collected as a part of a large national research project in Finland during the years 2013–2019. The research was conducted at the time of national curriculum reform (FNBE (Finnish National Board of Education), 2014) and the data collection followed the first 3 implementation years.

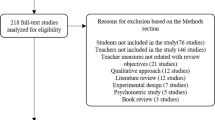

Seventy-five schools were selected using clustered sampling and a socio-economic status (SES) index that allowed us to identify schools from low and high socio-economic areas (see more in Pietarinen et al., 2021; Tikkanen et al., 2021). The sample of schools was representative of Finnish comprehensive schools, as the schools varied in size, setting (rural/urban), and SES (low/high) and were located all over Finland. Both students and teachers in the schools participated in the study, which enabled a two-level research design. The student and teacher survey data were collected in schools by a member of the research team. The student data was collected during one class and teacher data during teacher meetings.

In the present study, we utilised data collected in autumn 2017 and 2018 from 4th- to 5th-grade primary school students and their class teachers. Altogether, 2401 fourth graders (49.1% girls) in 149 primary school classes participated in 2017. The class size varied from 5 to 33 students, and the response rate was 83% at T1. The same students were followed up in the fifth grade (N = 2067), and the missing data was mainly explained by school absences and school changes of the students. In addition, 1585 comprehensive school teachers participated in the study in 2017, of which 102 class teachers were included in this study.

Finally, we included in this study all class teachers who were identified as teaching a specific primary school class in the study and the primary school students in these primary school classes (see Table 1 for exact numbers of participants in the analysis). Students who did not have an identifiable class teacher, who changed class during 2017–2018, or whose teacher changed during 2017–2018 were removed from the analysis.

Data collection followed the guidelines for responsible conduct of research and ethical principles of the Finnish Advisory Board on Research Integrity (2019) and was based on informed consent. The study did not require an ethical evaluation, as the study did not address sensitive topics and did not cause risks for the participants. Participation was voluntary for the students and teachers, and parental consent was required for student participation. Research permission was also obtained from the districts and municipalities of the schools.

Measures

We used two scales to measure the study well-being of the primary school students: study engagement and study burnout, and one scale to measure class teachers’ professional agency (teacher’s professional agency in the classroom). The reliability of the scales was good (Cronbach’s alphas varied from 0.80 to 0.94, see Table 1). The items of the scales can be seen in the Appendix.

Study engagement

The Study engagement scale (9 items) measured energy, dedication, and absorption in studying (Schaufeli et al., 2002). Study engagement was measured using a 7-point Likert scale (1, fully disagree; 7, fully agree).

Study burnout

The Study burnout scale (7 items) was adapted from the School Burnout Inventory (Salmela-Aro et al., 2009). Study burnout was measured using a 7-point Likert scale (1, fully disagree; 7, fully agree).

Teacher’s professional agency in the classroom

The Teacher’s professional agency in the classroom scale comprises two subscales: Collaborative environment and transformative practice (6 items) and Reflection in the classroom (4 items) (Heikonen et al., 2017; Pietarinen et al., 2016; Pyhältö et al. 2012, 2014; Soini et al., 2016; Yli-Pietilä et al., 2023a, b). The scale measures the teacher’s motivation, efficacy beliefs, and strategies for learning, which form the key components of teacher’s professional agency (Edwards, 2005; Sachs, 2000; Turnbull, 2005). Teacher’s professional agency in the classroom was measured using a 7-point Likert scale (1, fully disagree; 7, fully agree).

Analysis

First, we conducted preliminary examinations and tests on the data using IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 25). The student and teacher data collected in 2017 and 2018 was used in the analysis in the following way. We included the responses from the students whose class teacher was known and then combined the variables of teachers’ professional agency from these teachers in the student data. After that, we conducted a missing data analysis using Little’s MCAR test (Little, 1988). The univariate percentage ranged from 2.4 to 35.7 and the data was missing completely at random (χ2(44) = 51,980, p = 0.191) according to Little’s MCAR test. Thus, we used the full-information maximum likelihood procedure in the analysis.

Then, we examined the intra-class correlations (ICC) and design effects (Deff) for the study engagement and study burnout scales due to the nested structure of the data and two-level research design (Snijders & Bosker, 1999). The students were nested in the classes, so we used the classes as a clustering variable. The ICCs indicate statistically significant class-level differences, and it has been suggested that ICCs above 0.05 and Deffs over 1.1. or 2 indicate the need for multilevel analysis of the data (Lai & Kwok, 2015; Thomas & Heck, 2001).

Second, we tested three two-level structural equation models, each consisting of a within-class level (students within classes) and a between-classes level, using the Mplus program (version 8.6, Muthén & Muthén, 2010). The robust maximum likelihood (MLR) estimator was utilised due to the slightly non-normally distributed data.

The first model we tested was a two-level model of study well-being, which included only data from the students. In the second and third models, we tested both directions of the relation between teacher’s professional agency and study well-being.

Statistically insignificant paths were removed from the model. Several model fit indices were used to evaluate the model fit: the Chi-squared test of model fit, the Root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), the Comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and the Standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR). The following cut-off criteria were applied to reach a good model fit: a non-significant chi-squared test value, CFI and TLI both above 0.95, RMSEA below 0.05, and SRMR below 0.06 (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Results

The primary school students experienced relatively high study engagement (T1: 4.53, T2: 4.26) and low study burnout (T1: 2.76, T2: 2.80) during the 4th and 5th grade (Table 1). Sense of study engagement decreased, whereas study burnout increased slightly during the follow-up. The class teachers of the students experienced high professional agency in the classroom, especially reflection (CLE: 5.45, REF: 5.90). Students’ study engagement and study burnout correlated with each other in the expected directions within (student) and between (class) levels. Teacher’s sense of professional agency was also related to the study well-being components at the class level, except Collaborative environment and transformative practice at T1 and Reflection in the classroom at T2, which did not correlate statistically significantly with study engagement at the class level.

The intra-class correlations and design effects (N = 1875–1893; ICC(min–max) = 0.037–0.075; Deff(min–max) = 1.48–1.97) showed that there was variation in students’ experiences of study engagement and study burnout (see Table 1). As the ICCs and Deffs indicated only small variations at the class level, it is important to note that most of the variation in study engagement and study burnout experienced by the students was at the individual level. The variation between the classes was larger at the second time of measurement for study engagement and study burnout.

Two-level cross-lagged panel model of study well-being

The two-level path model was tested to analyse the structure of study well-being at the individual student level and the classroom level over a 1-year period. The results showed that the model (Fig. 4) fitted the clustered data well: χ2(5, N = 2036/141) = 9.647, p = 0.0859, RMSEA = 0.021, CFI = 0.997 TLI = 0.989, SRMR = 0.008.

The results showed that study engagement and study burnout were related at the student and class levels. Both study engagement and study burnout predicted themselves relatively strongly over time and predicted each other slightly negatively at the student level (see Fig. 4). At the class level, study burnout predicted itself very strongly over time and was negatively related to study engagement over time. Study engagement correlated with study burnout at T1 but had no other relations at the class level.

Gender was related to study well-being in that girls had a higher likelihood of experiencing higher study engagement and lower study burnout at the student level. Class size was not related to students’ experience of study well-being at the class level.

Two-level models of teacher’s professional agency and study well-being

The relationship between class teacher’s sense of professional agency and experienced study well-being was tested in both directions in two alternative models. Both models fitted the data well; the model fit for the first model (teacher’s professional agency as a predictor) was χ2(2, N = 1930/139) = 0.734, p = 0.6928, RMSEA = 0.000, CFI = 1.000, TLI = 0.1.000, SRMR = 0.000 and for the second model (Study well-being as a predictor) χ2(2, N = 1924/139) = 0.253, p = 0.8811, RMSEA = 0.000, CFI = 1.000, TLI = 0.1.000, SRMR = 0.001.

The models showed that teacher’s sense of professional agency did not predict study engagement or study burnout over time at the classroom level. Instead, the results showed that study burnout had a moderate negative effect on class teacher’s sense of professional agency at the classroom level (see Fig. 5). The effect was slightly higher for the collaborative learning environment and transformative practice mode than for the reflection in the classroom mode of professional agency.

Discussion

Theoretical implications

The aim of this study was to examine the sense of individual student and class group study well-being in the primary school class and to examine how the class teacher’s sense of professional agency is related to experienced study well-being.

The results of the study well-being are in line with previous research. In the light of this study, Finnish 4th- to 5th-grade students experience rather high study engagement, they get excited about studying and consider it meaningful (Rautanen et al., 2022; Ulmanen et al., 2022, 2023; Yang et al., 2022). However, there was a slight decrease in the sense of study engagement during the 1-year follow-up, which is in line with previous research (Blumenfeld et al., 2005; Luo et al., 2009; Kiuru et al., 2020; Salmela-Aro et al., 2016; Ulmanen et al., 2022; Wang & Eccles, 2012). Moreover, the students in this study also reported moderate levels of study burnout, i.e. they are sometimes tired and find schoolwork and going to school burdening. The experience of study burnout also increases slightly during the follow-up as shown in many previous studies (Maksniemi et al., 2018; Lindfors et al., 2018; Salmela-Aro, 2017; Tikkanen et al., 2021). Moreover, the results show that Finnish primary school students’ individual experiences of study engagement and study burnout were strongly linked to each other in fourth and fifth grade, implying that they predict each other (see also Yang et al., 2022; Salmela-Aro et al., 2016; af Ursin et al., 2021). This means that the experience of the importance of studying and the joy of learning are likely to remain stable as the school years go by. Similarly, exhaustion and loss of meaningfulness in relation to schoolwork can be difficult to turn around.

However, this study also examined the study engagement and burnout experienced collectively in the primary school class group, which is a much less studied angle of student well-being even though the social nature of the phenomena and the importance of studying these in communities and groups have been recognized (Choi, 2018; Roffey, 2015). In the light of the study, it seems that study burnout experienced among the students in the class group is likely to strengthen over time and to also weaken the group’s enthusiasm for studying and enjoying learning. In contrast, no similar relations were found in relation to experienced study engagement among the students in the class group. Although both phenomena have been found to spread in and across the group (Cho et al., 2023; Havik & Westergård, 2020; Kindermann, 2007; Kiuru et al., 2008, 2009; Lindfors et al., 2018; Meredith et al., 2020; Ouweneel et al., 2011; Salmela-Aro, 2017; Tikkanen et al., 2021; Tuominen-Soini & Salmela-Aro, 2014), the present study shows that study burnout seems to have a dominant impact on study well-being and its development in the primary school class group.

The study also examined the effect of gender and class size on study well-being in the primary school class group. It seems that 4th- and 5th-grade girls in primary school are more likely to experience higher levels of study engagement and lower levels of study burnout than boys, which is in line with previous research (e.g. Salmela-Aro & Tynkkynen, 2012). Class size, however, had no effect on experiences of study well-being in class. This may have been influenced by the fact that the average class size in the study was quite small (5 to 33 students) or because the class size effect remains hidden when studied together with other relations. Similar results regarding class size have been obtained in other studies with respect to social support in class (Rautanen, 2022; Vainikainen et al., 2017).

The study revealed a relation between the class teacher’s sense of professional agency and the study well-being experienced in the primary school class group. As in our previous studies on Finnish teachers, the class teachers in this study experienced strong professional agency in the classroom, in other words, they strive for shared learning in the classroom and also reflect on their teaching practice and development as teachers (Pietarinen et al., 2016; Soini et al., 2016; Yli-Pietilä et al., 2023a, 2023b). In the light of this study, when the class teacher has a strong sense of professional agency the students in the class are likely to experience higher study engagement and lower study burnout. However, the relationship with study burnout was stronger. The burnout experienced in the class group seemed to challenge and undermine the class teacher’s sense of professional agency, especially teacher’s efforts to build a collaborative environment in the classroom and transform practices together with students. This finding indicates that, when working with a burdened group of students, teacher’s learning may narrow down to reflecting only one’s own activities and no longer focus as much on tuning in the interaction and activities of the student group.

Practical implications

Class teachers’ warm relationship and reciprocal interaction with students are shown to be crucial for study well-being in the classroom (Kiefer et al., 2015; Konu et al., 2002; Lindfors et al., 2018; Løhre et al., 2010; Pietarinen et al., 2014; Rautanen et al., 2022; Ulmanen et al., 2022, 2023). We know also that learning together inspires teachers and students in the classroom (Darling-Hammond, 2008; Darling-Hammond et al., 2022; Soini et al., 2016; Yli-Pietilä et al., 2023a, 2023b). When learning is collaborative and shared in the classroom, students’ study engagement is likely to increase (Saariaho et al., 2019). However, the results of this study imply that this is not possible if severe study burnout is experienced among the students in the class.

These findings raise two important issues. We need to pay serious attention to (1) the well-being experienced in student groups and (2) supporting the professional agency of teachers, especially when encountering student groups with increasing and spreading experiences of study burnout, as we also know that lower levels of professional agency can increase teachers’ risk of burnout (Heikonen et al., 2017, Soini et al., 2016; Yli-Pietilä et al., 2023a, 2023b), that exhaustion tends to be contagious and that teacher exhaustion can be transmitted again to students (Tikkanen et al., 2021). To break this treadmill of burnout, we need to find new ways to support teachers in working with exhausted students.

Supporting teachers with student groups that experience high levels of study burnout calls for larger structural changes in schools and teachers’ working conditions. We know that one of the most powerful ways to protect against teacher and student burnout is to have close and warm relationships between students and teachers (e.g. Corbin et al., 2019; Hajovsky et al., 2020), and one way to support that is to create space for teachers to build relationships by providing them the time and resources to do so through structural changes. This may include, for example, providing more designated time for teamwork and collaboration with other teachers to share experiences and plan and carry out ideas. However, the learning and agency of class teachers should not be supported only by increasing formal training or focusing only on individual teachers, rather the most effective support is achieved from within the community by supporting an attitude of shared learning, confronting challenging situations together, and focusing on proactive actions (Pyhältö et al., 2015; Soini et al., 2010; Yli-Pietilä et al., 2023a). This is especially important from the perspective of preventing student exhaustion and teacher’s professional agency decline. But what else can the teacher do in the classroom?

As more and more classes face student well-being challenges, teachers are being increasingly required to focus on tuning classroom activities towards promoting study well-being. The teacher is challenged to seek solutions to reduce students’ experiences of the perceived insignificance of schoolwork, their concerns associated with studying, and the burden associated with schoolwork. From the perspective of teacher’s professional agency, this could mean that the teacher increasingly focuses classroom activities on learning how to buffer exhaustion, excessive workload, and cynical attitudes in the class community. It may be useful for the teacher to consider the following questions with the class and then to seek common practices to tackle the issues raised. Is it allowed in our class to say that you are tired and find schoolwork overloading? What things increase the workload and sense of constant rush in our class, and what things reduce these? Do we discuss together why we feel that schooling is important? Do we recognize each other’s strengths and preferences when it comes to school? Do we dare to say when we need help, and do we offer help to others?

Methodological reflection

There are limitations to this study to be considered. Firstly, the variation was small at the class level for the study engagement and study burnout variables, especially at the first time of measurement. It is generally accepted that statistically significant classroom-level differences can only be examined when ICCs are above 0.05 and Deffs over 2 (Thomas & Heck, 2001). However, it has been suggested that class-level variation can be studied at a lower threshold, at Deffs over 1.1 (Lai & Kwok, 2015), and this precondition was met for all of the studied variables. This should be taken into account when interpreting the classroom-level variation. For example, most of the variance in experienced study engagement was at the individual level, so it may be that the connections did not appear at the class level. Secondly, the study engagement and study burnout scales need still further validation in younger age groups and student populations as they have been used in this form only in this national research project, even though they stem from previous research on school well-being (Salmela-Aro et al., 2009; Schaufeli et al., 2002). Thirdly, there is multicollinearity and a standardized regression coefficient over 1 in the two-level model of study well-being at the class level. This is likely to happen when the model is quite simple and there are only few variables that are highly related. The standardized regression coefficients over 1 may occur when two variables are strongly related, which is understandable in this study for repeated burnout variables (Deegan, 1978). The results indicate that at the class level study engagement and study burnout may at least partially occur as each other’s counterparts.

In the future, it would be important to study the relation between teacher's professional agency and study well-being in longer-term studies. In addition, it would be worth considering applying and adapting the study to the well-being measure of younger primary school students, as there are still only few studies focusing on students under ten years of age.

References

af Ursin, P., Järvinen, T., & Pihlaja, P. (2021). The role of academic buoyancy and social support in mediating associations between academic stress and school engagement in Finnish primary school children. Scandinavian journal of educational research, 65(4), 661–675.

Blumenfeld, P., Modell, J., Bartko, W.T., et al. (2005). School engagement of inner-city students during middle childhood. In C. Cooper, C. Coll, W. Bartko, H. Davis, C. Chatman (eds.). Developmental pathways through middle childhood: rethinking contexts and diversity as resources. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410615558

Cho, S., Lee, M., & Lee, S. M. (2023). Burned-out classroom climate, intrinsic motivation, and academic engagement: Exploring unresolved issues in the job demand-resource model. Psychological Reports, 126(4), 1954–1976.

Choi, A. (2018). Emotional well-being of children and adolescents: Recent trends and relevant factors. OECD Education Working Papers, No. 169, OECD Publishing: Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/41576fb2-en

Corbin, C. M., Alamos, P., Lowenstein, A. E., Downer, J. T., & Brown, J. L. (2019). The role of teacher-student relationships in predicting teachers’ personal accomplishment and emotional exhaustion. Journal of School Psychology, 77, 1–12.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2008). Teacher learning that supports student learning. Teaching for Intelligence, 2(1), 91–100.

Darling-Hammond, L., Wechsler, M. E., Levin, S., & Tozer, S. (2022). Developing effective principals: What kind of learning matters? Learning Policy Institute. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED620192

Deegan, J. (1978). On the occurrence of standardized regression coefficients greater than one. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 38(4), 873–888.

Deng, X., Chen, T., Zhang, Z., Zhang, H., & Luo, H. (2022). Factors predicting academic burden and stress for primary-school students: Regression analysis based on a large-scale survey. Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Education Technology and Computers (549–554). https://doi.org/10.1145/3572549.3572637

Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2011). Schools as developmental contexts during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 225–241.

Edwards, A. (2005). Relational agency: Learning to be a resourceful practitioner. International Journal of Educational Research, 43(3), 168–182.

Estell, D. B., & Perdue, N. H. (2013). Social support and behavioral and affective school engagement: The effects of peers, parents, and teachers. Psychology in the Schools, 50(4), 325–339.

FIHW (Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare) (2021). School health survey 2019–2021. https://sampo.thl.fi/pivot/prod/fi/ktk/ktk4/summary_trendi2. Accessed 20 Mar 2023.

FNBE (Finnish National Board of Education) (2014). National Core Curriculum for Basic Education 2014. Helsinki: Finnish National Board of Education. http://www.oph.fi/english/curricula_and_qualifications/basic_education/curricula_2014. Accessed 20 Nov 2022.

Graham, A., Powell, M. A., & Truscott, J. (2016). Facilitating student well-being: Relationships do matter. Educational Research, 58(4), 366–383.

Hajovsky, D. B., Chesnut, S. R., & Jensen, K. M. (2020). The role of teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs in the development of teacher-student relationships. Journal of School Psychology, 82, 141–158.

Havik, T., & Westergård, E. (2020). Do teachers matter? Students’ Perceptions of Classroom Interactions and Student Engagement. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 64(4), 488–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2019.1577754

Heikonen, L., Pietarinen, J., Pyhältö, K., Toom, A., & Soini, T. (2017). Early career teachers’ sense of professional agency in the classroom: Associations with turnover intentions and perceived inadequacy in teacher–student interaction. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 45(3), 250–266.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Kiefer, S. M., Alley, K. M., & Ellerbrock, C. R. (2015). Teacher and peer support for young adolescents’ motivation, engagement, and school belonging. Rmle Online, 38(8), 1–18.

Kindermann, T. A. (2007). Effects of naturally existing peer groups on changes in academic engagement in a cohort of sixth graders. Child development, 78(4), 1186–1203. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01060.x

Kiuru, N., Nurmi, J. E., Aunola, K., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2009). Peer group homogeneity in adolescents’ school adjustment varies according to peer group type and gender. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 33(1), 65–76.

Kiuru, N., Wang, M. T., Salmela-Aro, K., Kannas, L., Ahonen, T., & Hirvonen, R. (2020). Associations between adolescents’ interpersonal relationships, school well-being, and academic achievement during educational transitions. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(5), 1057–1072.

Kiuru, N., Aunola, K., Nurmi, J. E., Leskinen, E., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2008). Peer group influence and selection in adolescents' school burnout: A longitudinal study. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 54(1), 23–55. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23096078

Konu, A. I., Lintonen, T. P., & Autio, V. J. (2002). Evaluation of well-being in schools–A multilevel analysis of general subjective well-being. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 13(2), 187–200.

Korhonen, J., Linnanmäki, K., & Aunio, P. (2014). Learning difficulties, academic well-being and educational dropout: A person-centred approach. Learning and Individual Differences, 31, 1–10.

Lai, M. H. C., & Kwok, O. (2015). Examining the rule of thumb of not using multilevel modeling: The “design effect smaller than two” rule. The Journal of Experimental Education, 83(3), 423–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2014.907229

Lam, S. F., Wong, B. P. H., Yang, H., & Liu, Y. (2012). Understanding student engagement with a contextual model. In S. L. Christenson, A. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 403–419). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7_19

Larsen, A. F., Leme, A. C., & Simonsen, M. (2020). Pupil Well-being in Danish Primary and Lower Secondary Schools. Aarhus University, Department of Economics and Business Economics.

Li, Y., & Lerner, R. M. (2011). Trajectories of school engagement during adolescence: Implications for grades, depression, delinquency, and substance use. Developmental Psychology, 47(1), 233.

Lindfors, P., Minkkinen, J., Rimpelä, A., & Hotulainen, R. (2018). Family and school social capital, school burnout and academic achievement: A multilevel longitudinal analysis among Finnish pupils. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 23(3), 368–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2017.1389758

Little, R. J. A. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83(404), 1198–1202. https://doi.org/10.2307/2290157

Løhre, A., Lydersen, S., & Vatten, L. J. (2010). School wellbeing among children in grades 1–10. BMC Public Health, 10(1), 1–7.

Luo, W., Hughes, J. N., Liew, J., & Kwok, O. (2009). Classifying academically at-risk first graders into engagement types: Association with long-term achievement trajectories. Elementary School Journal. https://doi.org/10.1086/593939

Maksniemi, E., Hietajärvi, L., Lonka, K., Marttinen, E., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2018). Sosiodigitaalisen osallistumisen, unenlaadun ja kouluhyvinvoinnin väliset yhteydet kuudesluokkalaisilla. Psykologia, 53(2–3), 180–200.

Meredith, C., Schaufeli, W., Struyve, C., Vandecandelaere, M., Gielen, S., & Kyndt, E. (2020). ‘Burnout contagion’ among teachers: A social network approach. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 93(2), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12296

Milkie, M. A., & Warner, C. H. (2011). Classroom learning environments and the mental health of first grade children. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52(1), 4–22.

Muthén, L., & Muthén, B. (2010). Mplus Users Guide (6th ed.). Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

Oberle, E., & Schonert-Reichl, K. A. (2016). Stress contagion in the classroom? The link between classroom teacher burnout and morning cortisol in elementary school students. Social Science & Medicine, 159, 30–37.

OECD (The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development). (2018). Teaching and learning international survey (TALIS). https://www.oecd.org/education/talis/talis-2018-data.htm. Accessed 15 Mar 2022.

Ouweneel, E., Le Blanc, P. M., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2011). Flourishing students: A longitudinal study on positive emotions, personal resources, and study engagement. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(2), 142–153.

Palmgren, M., Pyhältö, K. M., Pietarinen, J. & Soini, T. (2017). Students’ engaging school experiences: A precondition for functional inclusive practice. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 13(1). https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fe2017111550718

Pietarinen, J., Soini, T., & Pyhältö, K. (2014). Students’ emotional and cognitive engagement as the determinants of well-being and achievement in school. International Journal of Educational Research, 67, 40–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2014.05.001

Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., & Soini, T. (2014). Comprehensive school teachers’ professional agency in large-scale educational change. Journal of Educational Change, 15(3), 303–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-013-9215-8

Pietarinen, J., Pyhältö K., & Soini, T. (2016). Teacher’s professional agency – a relational approach to teacher learning. Learning: Research and Practice, 2(2), 112–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/23735082.2016.1181196

Pietarinen, J., Pyhältö, K., Soini, T., Haverinen, K., & Leskinen, E. (2021). Is individual- and school-level teacher burnout reduced by proactive strategies? International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 9(4), 340–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2021.1942344

Pyhältö, K., Soini, T., & Pietarinen, J. (2010). Pupils’ pedagogical well-being in comprehensive school—significant positive and negative school experiences of Finnish ninth graders. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 25(2), 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-010-0013-x

Pyhältö, K., Soini, T., & Pietarinen, J. (2012). Do comprehensive school teachers perceive themselves as active professional agents in school reforms? Journal of Educational Change, 13(1), 95–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-011-9171-0

Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., & Soini, T. (2015). Teachers’ professional agency and learning – from adaption to active modification in the teacher community. Teachers & Teaching, 21(7), 811–830. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2014.995483

Raniti, M. B., Allen, N. B., Schwartz, O., Waloszek, J. M., Byrne, M. L., Woods, M. J., Bei, B., Nicholas, C. L., & Trinder, J. (2017). Sleep duration and sleep quality: associations with depressive symptoms across adolescence. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 15(3), 198–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2015.1120198

Rautanen, P., Soini, T., Pietarinen, J., & Pyhältö, K. (2022). Dynamics between perceived social support and study engagement among primary school students: A three-year longitudinal survey. Social Psychology of Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-022-09734-2

Rissanen, I., Laine, S., Puusepp, I., Kuusisto, E., & Tirri, K. (2021). Implementing and evaluating growth mindset pedagogy–A study of Finnish elementary school teachers. Frontiers in education, 6, 753–698. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.753698

Roffey, S. (2015). Becoming an agent of change for school and student well-being. Educational & Child Psychology, 32(1), 21–30.

Saariaho, E., Toom, A., Soini, T., Pietarinen, J., & Pyhältö, K. (2019). Student-teachers’ and pupils’ co-regulated learning behaviours in authentic classroom situations in teaching practicums. Teaching and Teacher Education, 85, 92–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.06.003

Sachs, J. (2000). The Activist Professional. Journal of Educational Change, 1, 77–94.

Salmela-Aro, K. (2017). Dark and bright sides of thriving−School burnout and engagement in the Finnish context. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 14, 337–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2016.1207517

Salmela-Aro, K., & Read, S. (2017). Study engagement and burnout profiles among Finnish higher education students. Burnout Research, 7, 21–28.

Salmela-Aro, K., & Tynkkynen, L. (2012). Gendered pathways in school burnout among adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 35(4), 929–939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.01.001

Salmela-Aro, K., & Upadaya, K. (2012). The schoolwork engagement inventory. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 28(1), 60–67.

Salmela-Aro, K., & Upadyaya, K. (2014). School burnout and engagement in the context of demands-resources model. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 84, 137–151.

Salmela-Aro, K., & Upadyaya, K. (2020). School engagement and school burnout profiles during high school–The role of socio-emotional skills. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 17(6), 943–964.

Salmela-Aro, K., Kiuru, N., Leskinen, E., & Nurmi, J. E. (2009). School burnout inventory (SBI): Reliability and validity. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 25(1), 48.

Salmela-Aro, K., Moeller, J., Schneider, B., Spicer, J., & Lavonen, J. (2016). Integrating the light and dark sides of student engagement using person-oriented and situation-specific approaches. Learning and Instruction, 43, 61–70.

Salmela-Aro, K., Muotka, J., Alho, K., Hakkarainen, K., & Lonka, K. (2019). School burnout and engagement profiles among digital natives in Finland: A person-oriented approach. In D. Strohmeier, P. Wagner, & B. Schober (Eds.), Bildung Psychology (pp. 79–93). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780203701140

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 25(3), 293–315.

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., Gonzales-Roma, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3, 71–92.

Soini, T., Pietarinen, J., & Pyhältö, K. (2016). What if teachers learn in the classroom? Teacher Development, 20(3), 380–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2016.1149511

Soini, T., Pietarinen, J., Pyhältö, K., & Tirri, K. (2014). The education context: strategies for promoting well-being and ethically sustainable problem solving in teacher pupil interactions. In D. Jindal-Snape & E. Hannah (Eds.), Exploring the dynamics of ethics in practice: Personal, professional and interprofessional dilemmas. Bristol: Policy Press.

Soini, T., Pyhältö, K., & Pietarinen, J. (2010). Pedagogical wellbeing: Reflecting learning and well-being in teachers’ work. Teaching and Teachers: Theory and Practice, 16, 735–751. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2010.517690

Snijders, T., & Bosker, R. (1999). Multilevel analysis. SAGE Publications.

Spilt, J. L., Koomen, H. M., & Thijs, J. T. (2011). Teacher wellbeing: The importance of teacher–student relationships. Educational Psychology Review, 23(4), 457–477.

Taxer, J. L., Becker-Kurz, B., & Frenzel, A. C. (2019). Do quality teacher–student relationships protect teachers from emotional exhaustion? The mediating role of enjoyment and anger. Social Psychology of Education, 22(1), 209–226.

Thomas, S. L., & Heck, R. H. (2001). Analysis of large-scale secondary data in higher education research: Potential perils associated with complex sampling designs. Research in Higher Education, 42(5), 517–540.

Tikkanen, L., Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., & Soini, T. (2021). Crossover of burnout in the classroom—is teacher exhaustion transmitted to students? International Journal of School & Educational Psychology., 9(4), 326–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2021.1942343

Toom, A., Pyhältö, K. & O’Connell Rust, F. (2015). Editorial: Teacher’s professional agency in contradictory times. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1044326

Toom, A., Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., & Soini, T. (2021). Professional agency for learning as a key for developing teachers’ competencies? Education Sciences, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11070324

Tuominen-Soini, H., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2014). Schoolwork engagement and burnout among Finnish high school students and young adults: Profiles, progressions, and educational outcomes. Developmental Psychology, 50(3), 649.

Tuominen-Soini, H., Salmela-Aro, K., & Niemivirta, M. (2012). Achievement goal orientations and academic well-being across the transition to upper secondary education. Learning and Individual Differences, 22(3), 290–305.

Turnbull, M. (2005). Student teacher professional agency in the practicum. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 33(2), 195–208.

Ulmanen, S., Rautanen, P., Soini, T., Pietarinen, J., & Pyhältö, K. (2023). How do teacher support trajectories influence primary and lower-secondary school students’ study well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 14,. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1142469

Ulmanen, S., Soini, T., Pietarinen, J., & Pyhältö, K. (2022). Development of students’ social support profiles and their association with students’ study wellbeing. Developmental Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001439

Vainikainen, M.-P., Hienonen, N., & Hotulainen, R. (2017). Class size as a means of three-tiered support in Finnish primary schools. Learning and Individual Differences, 56, 96–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2017.05.004

Virtanen, T. E., Lerkkanen, M. K., Poikkeus, A. M., & Kuorelahti, M. (2018). Student engagement and school burnout in Finnish lower-secondary schools: Latent profile analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 62(4), 519–537. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2016.1258669

Wang, M. T., & Eccles, J. S. (2012). Social support matters: Longitudinal effects of social support on three dimensions of school engagement from middle to high school. Child Development, 83(3), 877–895.

Weare, K., & Gray, G. (2003). What works in developing children’s emotional and social competence and wellbeing? DfES Publications.

Yang, D., Cai, Z., Tan, Y., Zhang, C., Li, M., Fei, C., & Huang, R. (2022). The light and dark sides of student engagement: Profiles and their association with perceived autonomy support. Behavioral Sciences, 12(11), 408.

Yli-Pietilä, R., Soini, T., Pietarinen, J., & Pyhältö, K. (2023a). Profiles of teacher’s professional agency in the classroom across time. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2023.2196536

Yli-Pietilä, R., Soini, T., Pietarinen, J. & Pyhältö, K. (2023b). Primary school teachers’ sense of professional agency and inadequacy in teacher–student interaction. Teacher Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2023.2295414

Zullig, K. J., Koopman, T. M., Patton, J. M., & Ubbes, V. A. (2010). School climate: Historical review, instrument development, and school assessment. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 28(2), 139–152.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Tampere University (including Tampere University Hospital).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Current themes of research:

We are interested in processes of change and actors that both make changes happen and are caught in the middle of them; engage, resist, and facilitate them. We view learning both as the aim and as the primary means of achieving and sustaining meaningful educational change. We ask how actors in different levels of the educational system could learn together and as individuals, and what are the regulators and possibilities for well-being and agency in processes of educational change?

Most relevant publications:

Pietarinen, J. Pyhältö, K. & Soini, T. (2016). Teacher’s professional agency – a relational approach to teacher learning. Learning: Research and Practice.https://doi.org/10.1080/23735082.2016.1181196

Soini, T., Pietarinen, J. & Pyhältö, K. (2016). What if teachers learn in the classroom? Teacher Development, 20(3).https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2016.1149511

Tikkanen, L., Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J. & Soini, T. (2021). Crossover of burnout in the classroom—is teacher exhaustion transmitted to students? International Journal of School & Educational Psychology. 9(4), 326-339.https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2021.1942343

Toom, A., Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J. & Soini, T. (2021). Professional agency for learning as a key for developing teachers’ competencies? Education Sciences 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11070324.

Ulmanen, S., Soini, T., Pietarinen, J., Pyhältö, K. & Rautanen, P. (2022). Primary and Lower Secondary School Students’ Social Support Profiles and Study Wellbeing. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 42(5).https://doi.org/10.1177/02724316211058061

Yli-Pietilä, R., Soini, T., Pietarinen, J., & Pyhältö, K. (2023). Profiles of teacher’s professional agency in the classroom across time. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research.https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2023.2196536

Appendix

Appendix

Table 2.

The item scale is from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yli-Pietilä, R., Soini, T., Pietarinen, J. et al. How is students’ well-being related to their class teacher’s professional agency in primary school?. Eur J Psychol Educ (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-023-00781-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-023-00781-7