Abstract

We aim to examine similarities and differences in the developmental patterns of habitual (HRM) and situational reading motivation (SRM). We investigated the correlated change of SRM and two aspects of HRM: habitual reading enjoyment and habitual reading for interest. The sample comprised N = 1508 students with four waves of data collections spaced approximately every 18 months. Applying multivariate curve-of-factors models, first we found a decline in all three aspects of reading motivation from T1 to T3, and a stable trajectory from T3 to T4. Second, all three aspects of reading motivation correlated strongly regarding time-specific aspects, as well as level and trend factors. Third, the two HRM aspects showed higher correlations than did any aspect of HRM with SRM. Implications of the correlated declines of HRM and SRM, and for future research on reading motivation in general, are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Proficient reading is one of the key competencies for academic success (Cooper et al., 2014) and for being a successful member of modern societies (Rychen & Salganik, 2003). Reading as a complex process (Kintsch, 1998) requires individuals not only to have specific cognitive attributes, such as a sufficient vocabulary (Cain et al., 2004), but also to be motivated to read (Schiefele et al., 2012). In fact, research has repeatedly illustrated the positive link between reading motivation (RM) and reading achievement (Guthrie et al., 1999; Park, 2011). Typically, RM is defined and measured as habitual RM (HRM) that “denotes the relatively stable readiness of a person to initiate particular reading activities” (Schiefele et al., 2012, p. 469). This may not, however, represent the typical reading situation in school, where students are often confronted with texts they did not choose to read, but that they must read to achieve a given learning goal. Thus, situational RM (SRM)—the motivation “to read a specific text in a given situation” (Schiefele et al., 2012, p. 469)—might be a relevant aspect of RM that is worth looking into, not merely in the school context. Moreover, it might be important to note that following Schiefele et al. (2012), we understand individual interest as different from RM since individual interest may initiate different behaviors (e.g., watching a documentary, going to a museum), while there is one dimension of HRM involving the intention to read to satisfy one’s interests that we refer to as habitual reading for interest (HRI; Möller & Bonerad, 2007).

In this paper, we focus on the question how HRM and SRM for texts that are not chosen voluntarily develop during adolescence. Aside from gaining knowledge about correlated change of HRM and SRM, this study may also give some insight into how similar both aspects of RM are, and thus, whether HRM as typically measured is a fair indicator of the presumably more relevant SRM in the school context.

While it is documented that HRM declines throughout students’ schooling careers (Archambault et al., 2010), to the best of our knowledge, there have not been any studies investigating change in SRM. We focused on SRM and two aspects of HRM—i.e., habitual reading for enjoyment (HRE): reading because this is experienced as enjoyable—and HRI: reading out of curiosity in a specific topic. We were interested in whether the levels of HRE, HRI, and SRM change over time and whether the trajectories follow a similar pattern for HRM and SRM, whether and how individual change in HRM and SRM is correlated, and whether and how HRM and SRM are correlated within time after controlling for level and change.

Habitual and situational reading motivation

RM, as a multifaceted construct (Schiefele et al., 2012), refers to internal processes to initiate and sustain reading activities (Conradi et al., 2014; Unrau & Quirk, 2014) and is linked to various individual variables, such as reading-related self-concept (Aunola et al., 2002). In situated expectancy-value theory (SEVT; Eccles & Wigfield, 2020), engagement in chosen activities results from expectancy of success and subjective task values. First, to predict expectancy of success, individuals draw on different sources to estimate their chances of success. In a reading-related activity, these may include individuals’ beliefs about their reading skills (Möller & Schiefele, 2004). Second, the subjective task value is affected by individuals’ intrinsic, attainment and utility value, as well as the perceived cost that a task might entail. This can also be applied to the domain of reading (Möller & Schiefele, 2004; Wigfield, 1997). In our study, we primarily focus on the aspect of intrinsic value regarding RM, i.e., the question whether students like reading itself. This HRE is closely related to the concept of involvement in reading (Wigfield & Guthrie, 1997). “Habitual” refers to the more or less stable intent of individuals to initiate and sustain reading-related activities (Guthrie & Wigfield, 2005; Schiefele et al., 2012). Alternatively, individuals could also have intrinsic topic-related RM (Schiefele, 1991), where reading functions as a tool for learning: Individuals may read not due to the reading activity itself, but rather because they are interested in a specific topic. Thus, HRI is similar to the concept of curiosity (Wigfield & Guthrie, 1997), since both capture RM as a means to learn more about a topic someone is interested in (cf. Schiefele et al., 2012). Despite the similarities between HRE and involvement as well as HRI and curiosity, we decided to stick with the terms HRE and HRI since they better capture the terms of the original German measure we used. Moreover, HRE and HRI might be seen as closely related aspects of intrinsic HRM capturing a common aspect of RM. However, both indeed have a different meaning. HRI is object-specific meaning that a text is read due to the topic it is dealing with, while HRE is activity-specific meaning that a person reads due to the positive experiences when reading (Schiefele, 1999). Moreover, there is some evidence for differential relations with reading performance (Retelsdorf et al., 2011) and reading texts of different genres (McGeown et al., 2016). Thus, we investigated both aspects of HRM as separate constructs.

In SEVT, Eccles and Wigfield (2020) further point out the importance of the situation for individuals’ motivation to engage in certain activities. Regarding motivation in reading-related activities, SRM refers to individuals’ motivation to read a specific text in a specific situation. SRM is related to the concept of situational interest; some authors even use these two labels interchangeably (Schiefele, 1999). Similar to SRM, situational interest “is conceptualized as a temporary state that is elicited by specific features of a text (e.g., personal relevance […])” (Schiefele, 1999, p. 258). Hence, assessments of situational interest and SRM may be seen as identical (Guthrie et al., 2005). However, situational interest is not necessarily limited to reading but can also be satisfied for example by watching a documentary. So, SRM might be seen as a particular aspect of situational interest. Finally, in school SRM is relevant in a context in which students are confronted with a particular text they cannot choose themselves, since it has been shown that it is related to a higher use of inference strategies (Tonks et al., 2021). Thus, it is of particular interest to see how students react to such given texts and in how far these texts can stimulate SRM.

Despite the little evidence that HRM and SRM correlate highly (Guthrie et al., 2007), in general, research investigating the relations of HRM and SRM is scarce. Most studies investigating RM focus on HRM rather than SRM. Hence, the empirical and theoretical reasoning for our research question and hypotheses is largely based on studies examining HRM, unless explicitly stated otherwise.

The development of habitual and situational reading motivation

Despite research repeatedly suggesting the importance of RM for reading achievement (Guthrie & Wigfield, 1999; Guthrie et al., 2007), studies investigating the development of RM in longitudinal studies have been scarce. This holds true especially regarding SRM.

Regarding the development of (intrinsic) RM, a steady decline has repeatedly been noted across grades. Archambault et al. (2010) found that the intrinsic RM of approximately 90% of students declined from grade 1 to 12, regardless of gender, family income, grades, and parental perceptions of the students’ reading abilities. McElvany et al. (2008) found a decline of RM in the transitioning from primary to secondary education. A decline has also been noted in the course of secondary education (Gottfried et al., 2001), even after controlling for gender, parental socioeconomic status, and school track (Miyamoto et al., 2020). Considering the utter importance of RM for reading achievement and skill growth (Retelsdorf et al., 2011), this downward trend in HRM is concerning. To date, many possible reasons for the decline of intrinsic RM have been discussed (see Gottfried et al., 2009). Self-determination theory provides a reasonable explanation for adolescents’ decline of general intrinsic motivation. According to this theory, individuals have three basic psychological needs: relatedness, competence, and autonomy (Deci & Ryan, 1985, 2000). If one of these needs is not met, intrinsic motivation might decline (Gnambs & Hanfstingl, 2016). For instance, as individuals’ striving for autonomy increases during puberty, teachers appear to have trouble establishing a balance between individuals’ needs and the demands of school curricula (Hunt, 1975; Köller & Baumert, 2008). Based on these findings, Eccles et al. (1993) postulated the stage-environment fit model. The authors suggest that this development pattern of intrinsic motivation may be traced back to the mismatch of school conditions and adolescent students’ needs. For instance, it is assumed that students develop more interests outside of school, meaning that activities that are (perceived as) school-related become less important to them (McElvany et al., 2008; Wigfield & Eccles, 1994).

In respect of SRM, most studies have focused on how it affects students’ long-term interest (for a review, see Shraw & Lehman, 2001); far fewer studies have investigated how SRM develops over time. One notable exception is the study by Guthrie et al. (2005) investigating whether HRM results from repeated SRM. They suggest that initial RM is qualitatively different compared to motivation in later stages. Beginning readers may initially read due to their interest in the topic of specific texts: They are situationally motivated to read. As individuals repeatedly read about topics they are interested in, positive emotions develop and will be linked to the activity of reading. For beginning readers, the increasing number of positive events linked to reading may lead to higher HRM.

Drawing on the results of their study, Guthrie et al. (2005) suggest that SRM might lead to higher HRM over time. In their study, third graders who over a span of 4 months increased their SRM also increased their HRM. However, the study was part of a RM program, so it is unclear whether these results are generalizable to regular classes. Guthrie et al. (2007) were able to corroborate these results for fourth graders: The data, however, did not allow testing the direction of the relations between SRM and HRM.

For older students, it seems even less clear whether SRM affects HRM or vice versa, since they are more experienced readers who might have developed HRM already. Again, research on this question is scarce. Locher et al. (2019) found for ninth graders that SRM was correlated with HRM, but only regarding school-related reading, not recreational reading. These differential correlations emphasize that it may be important to account for the concrete reading context when measuring RM. Typical measures of HRM, however, are usually rather broad and unspecific (e.g., “I like to read about new things”, Wigfield & Guthrie, 1997). Thus, it is important to learn how such broad measures relate to SRM in a similar-to-school situation (where students are required to read a given text).

In SEVT, Eccles and Wigfield (2020) point out the need for more research concerning situational values and expectancies and, furthermore, how these situational factors relate to broader outcomes. While research has repeatedly illustrated a decline in students’ intrinsic RM (Archambault et al., 2010), less is known about the situational aspect of RM. Thereby, it is important to learn more about the development of SRM, since (despite its situational nature) it might decline over the years meaning that it becomes more difficult to reach high levels of RM in later school. Moreover, this would indicate that there is some trait aspect in (the way we measure) SRM. Despite initial studies indicating that developments in SRM and HRM are related over a shorter course of time (Guthrie et al., 2005), we do not know much about the long-term development of SRM and how it relates to HRM.

The present investigation

Despite the large number of studies concerning the significance of RM for learning to read (see Schiefele et al., 2012 for a review), the development of RM itself has only seldom been the focus of research. As Gottfried et al. (2001) pointed out, examining change is important to get a better understanding of individuals’ developmental change; this may be especially true regarding different facets of RM. Developmental change regarding intrinsic HRM has been investigated repeatedly in recent decades, but less is known about the developmental change regarding SRM and the correlated change of HRM and SRM. As pointed out by Eccles and Wigfield (2020) in their SEVT, research regarding situational aspects of RM and how these relate to habitual aspects is needed to understand processes leading to individuals’ engagement in activities. Hence, in the present study, we were interested in the correlated development of two aspects of HRM (HRE and HRI) and SRM. Thereby, we were particularly interested in SRM as stimulated by given texts—a common situation in school, where students cannot search texts, they want to read, but rather they must read what their teachers choose.

Drawing on previous research and theoretical perspectives, we investigated two research questions. First, while previous research has illustrated that intrinsic HRM declines with age (Archambault et al., 2010), studies investigating developmental change in specific temporal facets of RM are missing. According to self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985, 2000) and in a similar vein to stage-environment fit model (Eccles et al., 1993), students’ needs change throughout puberty: They increasingly seek autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Therefore, adolescents increasingly value their social life (LaFontana & Cillessen, 2010) and attach more importance to social activities, compared to other (academic) activities (Wigfield & Eccles, 1994). Hence, we hypothesized a decline in the mean levels of HRE, HRI, and SRM.

Second, we aimed to investigate the correlated developmental change in both facets of HRM and SRM by investigating correlated change throughout secondary school. While it is known that HRM decreases across secondary school (Archambault et al., 2010), in respect of SEVT (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020), it is yet to be examined how SRM develops and how these developments relate to developmental change in HRM. For instance, HRM rather than SRM predicts desirable outcomes such as reading achievement (Retelsdorf et al., 2011). However, SRM is directly malleable in educational contexts, whereas HRM is not (Guthrie et al., 2005). Hence, investigating the correlated change in HRM and SRM might provide information on the relevance of motivation for reading a given text for HRM. We were particularly interested in similarities between the mean trajectories of HRM and SRM, in correlations between individual change in HRM and SRM, and in the correlations between HRM and SRM within time, controlling for level and change. Thereby, we investigated whether it seems plausible to expect a closer correlation between HRE and HRI than between both aspects of HRM and SRM. This might also help to better understand how situational SRM indeed is.

Method

Sample and procedure

We drew on a sample of N = 1508 students (49% girls, age at T1, M = 10.88 years, SD = 0.56) from 60 schools that were selected so as to be representative of the federal state of Schleswig–Holstein, Germany including the distribution of school tracks. The sample stemmed from the larger project LISA (in German: “Lesen in der Sekundarstufe” [Reading in secondary school]), which mainly deals with individual and contextual determinants of reading comprehension in secondary school (Retelsdorf et al., 2012, 2014).

We applied a longitudinal design with data collections approximately every 18 months: at the beginning of grade 5 (T1), the end of grade 6 (T2), the beginning of grade 8 (T3), and the end of grade 9 (T4). Each data collection took place within 14 days. Trained research students collected the data in class during regular lessons. Students first worked on reading tests, directly followed by the measure of SRM, before they answered a questionnaire including the measure of HRM.

This study was carried out in accordance with the ethical guidelines for research with human participants as proposed by the American Psychological Association. The study materials and procedures were approved by the Ministry of Education, Science and Cultural Affairs of the Federal State of Schleswig–Holstein. Participation was voluntary. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians.

Measures

Two aspects of HRM were measured with the ‘Habitual Reading Motivation Questionnaire’ (Möller & Bonerad, 2007). Students rated their agreement with each item on a 4-point Likert-type scale anchored at 1 (“does not apply to me”) and 4 (“applies to me”). First, we assessed students’ HRE—their intrinsic activity-related RM—with five items (e.g., “I enjoy reading books”). Cronbach’s α was good at all four waves of data collection (.88 to.93). Second, HRI was measured as intrinsic topic-related RM (e.g., “I like reading about new things”). We had to remove one item from the original scale, due to insufficient psychometric properties. The resulting scale comprised five items; Cronbach’s α was between .69 and .82.

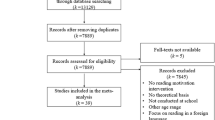

The SRM measures were incorporated into the assessment of reading achievement, which was tested with several short texts the students had to read. These age-appropriate tests have been well developed in the context of large-scale studies that differed from data collection to data collection. Immediately after reading each text, the items measuring SRM were administered. Only after answering these items did the students work on the test items. Since a varying number of texts was used for the assessment of reading achievement at each time point, the number of SRM assessments varied over time (Fig. 1): SRM was assessed two times at T1, six times at T2, five times at T3, and six times at T4. We measured SRM by two items following each text (“I found the text interesting”, “I enjoyed reading the text”). Students rated their agreement with each item on the same 4-point Likert-type scale as for HRM. Cronbach’s α was sufficient or better (α between .76 and .94). Only the reliability of the very first measure of SRM (SRM 1a in Fig. 1) was somewhat lower (α = .54). Since we did not use this variable as a predictor in our model and since we used latent variables accounting for the measurement error, this lower reliability should be negligible.

Statistical analyses

To analyze correlations between different aspects of the development of HRE, HRI, and SRM, we estimated a multivariate curve-of-factors model (McArdle, 1988) applying structural equation modeling for change, which can be interpreted similar to multilevel models of change (time-points nested within individuals; Singer & Willett, 2003). In our model, not only the parameters associated with the latent intercept and slope factors were estimated, but also the time-specific indicators for these factors were also represented by latent variables. With the growth models for each aspect of RM, we restricted factor loadings of the intercept factor to one and the average of all loadings on the slope factor to zero, with the loading of each T4 indicator being fixed to one. Thus, in our model, the intercept represents the average level of RM, and the slope factor represents the trend over time. Thus, latent variables representing HRE, HRI, and SRM at each data collection occasion served as indicators for these level and slope factors (HRE T1 to HRE T4 and SRM T1 to SRM T4 in Fig. 2, and HRI T1 to HRI T4 [not depicted]).

To evaluate the goodness of fit for all models χ2, CFI (comparative fit index), RMSEA (root-mean-square error of approximation), and SRMR (standardized root-mean-square residuals) are reported. We based the calculation of CFI not on the standard null model (unconstrained intercepts, variances, and covariances constrained to zero), since following Widaman and Thompson (2003), it is an improper comparison model for many models (e.g., growth curve models). Wu et al. (2009) recommend that for proper use of CFI a correct baseline model should be estimated manually. Following these recommendations, we calculated both fit indices manually using a null model in which the intercepts of the manifest items were constrained to be equal over time. For the SRM measures, this was true for the items following the identical texts at different data collection occasions (due to the applied anchor item design for the assessment of reading achievement). Mplus 8.6 (Muthén and Muthén, 1998-2021) was applied for all statistical analyses. We allowed correlations over time between the residuals of the repeated manifest indicators measuring HRE and HRI (Marsh & Hau, 1996). These correlations were also allowed between the residuals of SRM measures following identical texts at different data collection occasions. Moreover, for all these repeated manifest measures, the factor loadings and item intercepts were constrained to be equal over time. This assumption of measurement invariance is important, to ensure that the construct meaning of the latent factors is the same at every data collection (Little et al., 2007). Therefore, in preliminary analyses, we tested whether the assumption of measurement invariance is supported for our data. This is usually done by testing several steps of invariance that are defined by an increasing number of parameters that are constrained to be equal over time. Again, for SRM, these parameters have been constrained to be equal for measures following identical texts at different occasions of data collection. In each step, the model fit of the more restrictive model is then compared with the model fit of the less restrictive model. For larger samples, it has been suggested that support for the more parsimonious model requires a change in CFI of less than .01 or a change in RMSEA of less than .015 (Chen, 2007; Cheung & Rensvold, 2002) when testing measurement invariance. First, we tested a model assuming configural invariance, meaning that no parameters are constrained to be equal over time. Second, we tested weak factorial invariance by constraining the factor loadings to be equal over time. Third, strong invariance implies that the item intercepts are additionally constrained to be equal over time. This level of invariance is critical when investigating latent mean structures, since when strong invariance is supported, change in the mean levels of the indicators are adequately captured as change in the means of the latent variables (Little et al., 2007). Finally, a fourth step was tested, in which the item uniquenesses were additionally constrained to be equal over time, testing strict invariance.

Turning now to the description of the developmental trends for each type of RM, the model parameters of major interest for our research questions were three correlations. First, we were interested in the time-specific correlations between HRE, HRI, and SRM, i.e., the correlations between the latent indicator residuals controlling for level and trend at each data collection (rTS in Fig. 2). These correlations were constrained to be equal over time (rTS1 = rTS2 = rTS3 = rTS4). Second, we were interested in the correlations between the three level factors (rL in Fig. 2) and third, in the correlations between the three trend factors (rT in Fig. 2) indicating correlated change in the two aspects of HRM and in SRM. For a clearer interpretation of this correlated change, we tested whether the time-specific factor loadings on the trend factor could be constrained to be equal for all three aspects of RM (λHRI1 = λHRE1 = λSRM1 etc.; Fig. 2). Thus, the shape of change was constrained to be identical for HRE, HRI, and SRM. A further question, approached on the basis of the multivariate curve-of-factors model, was whether the intercepts and slopes of HRE, HRI, and SRM reflect a general change process that underlies all three constructs. This can be formalized by adding an additional layer to the model, such that the constructs’ intercepts and slopes are expressed as indicators of two underlying latent variables.

On average, about 22.9% of the data per variable were missing. We applied multiple imputations to handle missing data (see Graham, 2009). We created m = 50 imputed data sets, which is considered to be sufficient for our level of missing data. All subsequent analyses were then conducted 50 times; the results were automatically combined by Mplus.

The plausibility of models with different levels of restrictions can be evaluated on the basis of a χ2-difference test. Since we estimated unbiased standard errors for the hierarchical data structure (students nested in schools) using the Mplus option “type = complex” with a robust maximum-likelihood estimator (MLR) combined with multiple imputations, χ2-difference tests cannot be straightforwardly applied (Jang et al., 2015). As a solution, we applied a Wald test, which avoids the problem of combing the log-likelihood functions and which uses the MLR-based covariance matrix for the parameter estimates. In our case, the Wald test tests whether the restrictions added to the model as described above lead to a statistically significant decrease in the model fit. For the models we tested, this approach was quite straightforward, with one exception. For the model assuming that the constructs’ intercepts and slopes are expressed as indicators of two underlying latent variables, the suggested procedure asks the question whether the covariances between the intercept and slope factors can be explained by the covariances of two latent factors that can be extracted on the basis of the covariances among the intercepts and the slopes, respectively. Therefore, a statistically significant Wald test rejects the hypothesis of a general change process.Footnote 1

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations

As presented in Table 1, within each aspect of RM, the means at T2 are smaller than at T1, and at T3, they are smaller than at T2, while they are similar between T3 and T4. Moreover, the correlations between HRE, HRI, and SRM within and across time were positive and significant. The strongest correlations turned out to be within the same construct across time, and between the two aspects of HRM, within and across time. These correlations were moderate to strong. This was also true for the within-time correlations between HRI and SRM. The remaining correlations were small to moderate in size.

Preliminary analyses

We tested measurement invariance over time in a series of models with 12 dimensions, for the three aspects of RM at the four data collections. First, we tested a model assuming configural invariance that fit the data well: χ2(1520) = 5194.09, CFI = .924, RMSEA = .040, SRMR = .044. Second, we tested a model with metric invariance by constraining the factor loadings of repeated measures to be equal over time. The model fit was adequate: χ2(1555) = 5513.32, CFI = .918, RMSEA = .041, SRMR = .064. Based on the guidelines presented, the differences in CFI and RMSEA supported the assumption of metric invariance: ΔCFI = .006, ΔRMSEA = .001. Third, strong invariance was tested by also constraining the intercepts of the repeated measures to be equal over time, resulting in an adequately fitting model: χ2 (1581) = 5773.08, CFI = .913, RMSEA = .042, SRMR = .066. The assumption of strong invariance was also supported: ΔCFI = .005, ΔRMSEA = .001. Fourth, testing strict invariance, we constrained the item uniquenesses of repeated measures to be equal over time. The resulting model fit of χ2(1616) = 6211.83, CFI = .905, RMSEA = .043, SRMR = .067 indicated that the assumption of strict invariance was supported by the data (ΔCFI = .008, ΔRMSEA = .001). Thus, all subsequent analyses were performed under the assumption of strict measurement invariance.

Multivariate curve-of-factors model

We first tested a basic multivariate curve-of-factors model for HRE, HRI, and SRM under the assumption of strict measurement invariance for the latent time-specific indicators over time. The model fitted the data adequately: χ2(1649) = 6354.64, CFI = .903, RMSEA = .043, SRMR = .057. Second, we tested a model in which the time-specific correlations (rT, Fig. 2) between the residuals of HRE, HRI, and SRM were constrained to be equal over time. The resulting model fit the data adequately: χ2(1658) = 6381.20, CFI = .903, RMSEA = .043, SRMR = .057. The Wald test indicated that there was no significant difference between the two models, χ2(9) = 16.74, p = .053, suggesting support for the more parsimonious model with constrained correlations. Third, we tested the assumption of an identical shape of growth for HRE, HRI, and SRM by constraining the factor loadings on the trend factors to be equal across all three aspects of RM (λHRE1 = λSRM1 etc.). Again, an adequately fitting model resulted: χ2(1662) = 6387.89, CFI = .902, RMSEA = .043, SRMR = .057; the Wald test indicated no significant difference: χ2(4) = 6.10, p = .192. Finally, we tested a model assuming that the constructs’ intercepts and slopes are expressed as indicators of two underlying latent variables to account for the shared variance of the three constructs in their initial levels and trends. This model, however, resulted in a solution with a negative but insignificant residual variance for the HRI change factor. Thus, we again tested the model, with this variance fixed to .00001. The resulting model fitted the data adequately: χ2(1671) = 6,492.23, CFI = .902, RMSEA = .044, SRMR = .060; the Wald test, however, indicated a significant difference to the previous model: χ2(8) = 58.86, p < .001. Thus, the previous model, with time-specific correlations over time and the shape of growth constrained to be equal but without common level and change factors, represented the data best; all results presented in the following are derived from this model (see Supplement S1 for computer code and parameter estimates).

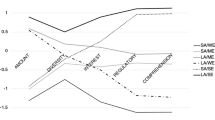

For all three aspects of RM, we found a significant decline (Table 2). The unstandardized factor loadings on the trend factors (Table 2) show that this decline took place from T1 to T3, while the nearly identical factor loadings from T3 to T4 indicated not much change. This becomes obvious also in the developmental trends for HRE, HRI, and SRM (Fig. 3). Moreover, the explained variance in the time-specific indicators increased from T1 to T3 but then stabilized, indicating that the proportion of variability due to systematic individual differences increased over time (Table 2).

The relations between HRE, HRI, and SRM were tested for three components of each aspect of RM estimated in the multivariate curve-of-factors model. First, the residuals of the time-specific latent variables representing HRE, HRI, and SRM were moderately correlated (rTS). A series of Wald tests indicated that the correlations between HRE and HRI were significantly higher than the correlation between HRE and SRM (χ2[1] = 27.79, p < .001), and the correlation between HRI and SRM (χ2[1] = 13.27, p < .001). No significant difference was recorded between the two correlations of HRE and HRI with SRM (χ2[1] = 2.05, p = .152). Second, moderate to high correlations resulted between the level factors (rL). The correlations between HRI and HRE (χ2[1] = 34.10, p < .001) and those between HRI and SRM (χ2[1] = 19.25.49, p < .001) were significantly higher than the correlation between HRE and SRM. No significant difference was found between the correlations of HRE and SRM with HRI (χ2[1] = 2.08, p = .149). Third, the correlations between the trend factors (rT) were also moderate to high: Only the correlations of HRE with SRM and HRI differed significantly (χ2[1] = 9.24, p = .002) with the higher correlation being that between HRE and HRI (Table 3). The correlations of HRE and HRI with SRM (χ2[1] = 1.20, p = .274) and the correlations of HRI with HRE and SRM (χ2[1] = 2.54, p = .111) did not differ significantly.

In sum, we found strong correlations between all three aspects of RM and change therein. Thus, although not significant in all cases, the correlations between the two HRM aspects were higher than the correlations between HRM and SRM. Finally, there was a tendency for HRI to be more highly correlated with SRM than HRE.

Discussion

Research investigating RM has been prevalent in the field of educational psychology in the past decades (Chapman & Tunmer, 1995; Retelsdorf et al., 2014). However, despite studies illustrating the importance of HRM for reading achievement and growth (Logan et al., 2011; Retelsdorf et al., 2011), longitudinal change in RM has received little attention. In fact, research on SRM is scarce in general, and studies investigating the correlated change of HRM and SRM are also lacking. It is important to gain more insight into this change to learn more about the decline of RM with age found in previous research, and to get a better idea of how closely the typical measure of HRM relates to SRM. Hence, the aim of this study was to investigate the correlated change of two aspects of HRM (HRE and HRI) and SRM. First, all three aspects of RM declined from T1 to T3, but not from T3 to T4. Second, individual differences became more stable over time. Third, all three aspects of RM were strongly correlated regarding time-specific aspects, level, and trend factors—even though the data are not best represented by a model postulating common factors in these level and trend factors. Fourth, HRE and HRI tended to correlate more highly with each other than with SRM. Fifth, HRI, rather than HRE, was linked more strongly to SRM. This seems explicable by dint of the fact that SRM is per se highly dependent on the level of interest in the particular text a student reads and thus, should be more closely related to the interest aspect of intrinsic HRM.

Theoretical and practical implications

Previous research repeatedly illustrated that intrinsic HRM declines throughout students’ school career (McElvany et al., 2008). In line with previous research, both facets of intrinsic HRM investigated in this study (HRE and HRI) declined from the beginning of fifth to the beginning of eighth grade. Interestingly, there was no further decline in students’ HRE or HRI to the end of ninth grade. Thus, it seems that students at this age reached a point where HRE and HRI stabilize, at a rather low level. This developmental trend well fits previous studies investigating older students. Gottfried et al. (2001) found a similar pattern at this age; however, this was followed by an increase in intrinsic RM between the ages of 16 and 17. They argue that this developmental increase in RM might be due to students’ realization that their school career is ending soon. Hence, consideration of grades and academic achievement may become more relevant, since students might start to plan their future career and consider applying for college.

Furthermore, Archambault et al. (2010) found different profiles of RM development from grade 1 to 12. First, around 30.3% of students showed a decline in intrinsic RM, with stable values found from grade 9 to grade 12. Second, approximately 28.3% of students showed a reverse U-shaped trajectory in their RM. Students hit their lowest point of intrinsic RM between grades 6 and 10, depending on the exact profile. Third, the largest proportion of students (41.4%) showed a constant decline in intrinsic RM. Considering these different trajectories, and the developmental trend in this study, our analytic sample might to a greater extent consist of students whose RM develops according to the first or second trajectory. One has to keep in mind, however, that Archambault et al. (2010) profiles were based on a considerably longer period of time, so the applicability of their results to our sample is only permissible with certain reservations.

Our findings are in line with previous research regarding the development of HRM in general, and expand these findings into HRE, HRI, and SRM: Both the HRM facets and SRM follow a similar developmental pattern from the beginning of grade 5 to the end of grade 9, resulting in moderately to highly correlated change. Thus, adolescents’ RM decreases regarding the reading activity itself (HRE), their RM for specific topics (HRI), and in specific situations (SRM).

An explanation for this downward trend may be found in stage-environment fit theory (Eccles et al., 1993), in which a mismatch between school environments and students’ needs is proposed. As students grow older, their desire for autonomy increases. However, it appears to be difficult for teachers to address their students’ needs, against the background of school curricula and institutional demands (Hunt, 1975; Köller and Baumert, 2008). There is empirical evidence in support of the assumptions of stage-environment fit theory: A learning environment that is orientated towards students’ need for autonomy affects students’ motivational development more positively (Wigfield et al., 1996). More specifically, students’ motivation and performance have been shown to increase when students are given choice and control (Guthrie & Humenick, 2004; Reynolds and Symons, 2001). At this point, three aspects are important to note. First, HRM rather than SRM has been proven relevant to reading achievement (Guthrie et al., 2005) and skill growth (Logan et al., 2011; Retelsdorf et al., 2011). Future research should investigate whether this is also true for SRM, and whether well-evaluated methods such as CORI (concept-oriented reading instruction; Guthrie et al., 2004) for the enhancement of HRM should be further implemented in schools. Second, as pointed out by Guthrie et al. (2005), it is important to note that SRM is even more susceptible to educational interventions than HRM. Drawing on the situational motivation perspective (Schiefele et al., 2012), providing repeated situational support may increase SRM, which may lead to long-term HRM (Guthrie et al., 2005), even though the empirical evidence for this assumption has to date been rather weak. Third, RM interventions should take place early in school, since individual differences seem to become more stable over time.

Finally, our results on the one hand show that HRM and SRM develop quite similarly over time and are substantially correlated, suggesting that both may share a huge proportion of variance. This may be interpreted as an argument that typical measures of HRM perform well and allow for conclusions about the relevance of RM for particular achievement situations. On the other hand, the latent correlations in our study, and the worse-fitting model assuming that the constructs’ intercepts and slopes, are expressed as indicators of two underlying latent variables show that SRM and HRM may still measure quite different aspects of RM. Of course, further research is needed to gain more insight into the similarities and differences between SRM and HRM, but we think that it might be fruitful for research on RM if it were to take greater account of SRM in the future.

Limitations

Our study has limitations that need to be considered. First, our sample was taken from one federal state in Germany. It is unclear how far our results are generalizable to students in other parts of Germany and in different countries. Students’ reading skills vary between federal states in Germany (Artelt et al., 2002) and across countries (OECD, 2019). Since reading skills and RM are correlated (McElvany et al., 2008), this may affect RM development in different regions. Still, given the general trend across nations of declining RM when students grow older, we assume that our findings may be true in different (Western) countries.

Second, it is unclear whether and how the measurement of HRM and SRM in the same test session may have affected the results. It might be that the first measurement of SRM set an anchor and affected how students later answered the HRM items. However, we do not think that this is a threat to the validity of our results, because the contexts for these contrasting items were rather different. While SRM was assessed in a concrete achievement situation directly after the students had read a text, HRM was assessed within a larger questionnaire after a short break. Moreover, the items measuring SRM addressed the motivation for reading a particular text, while the HRM items were formulated more generally.

Third, in our model, we were not able to take a closer look at differences in SRM between the different texts within one wave. Of course, the students might have read the different texts with varying degrees of interest. Moreover, it might be that the texts became more boring over time, so that the decline in SRM was more the effect of a text than a student characteristic. Future research should focus on the effects of varying interest in different texts for RM. A promising approach to investigate this in more detail might be experimental research in which students’ SRM when they are allowed to choose texts of their own interest is compared to occasions when they are asked to read given texts. It would be interesting to see how these different types of SRM relate to general measures of HRM.

Conclusion

Most studies investigating RM so far have focused on the link between different dimensions of RM and reading achievement, in part considering possible mediators (see Schiefele et al., 2012). For instance, while the distinction between extrinsic versus intrinsic RM has received a lot of attention (Schiefele et al., 2012), the distinction between HRM an SRM has been mostly neglected. In our study, we addressed this lacuna and showed that two facets of HRM and their developments correlate moderately to highly with SRM. Thus, our results are in line with those of Guthrie et al. (2007), and expand these, adding a further developmental perspective. Our results highlight that teachers in secondary school should be aware both of enhancing students’ HRM and of creating particular situations in which the reading of texts is experienced as highly motivating—for example, through specific content or references to the adolescents’ lifeworld. Moreover, future research on RM should put focus more on SRM, to investigate its similarities to and differences from HRM.

Notes

The Wald test is based on the premise that the covariances among three variables imply an exactly identified factor model. We computed the factor loadings of the intercept factors on a higher order factor, and repeated this procedure for the slope factors. Based on these loadings, we estimated correlations between the two factors that provided the best account of the covariances between intercept and slope factors in the least squares sense. The Wald test was then used to examine whether the differences among the nine covariances of the intercepts with the slopes could be accounted for by the differences between previously computed factor loadings and the factor correlation. This Wald test provides a χ2-value with df = 8 degrees of freedom.

References

Archambault, I., Eccles, J. S., & Vida, M. N. (2010). Ability self-concepts and subjective value in literacy: Joint trajectories from grades 1 through 12. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102, 804–816. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021075

Artelt, C., Schneider, W., & Schiefele, U. (2002). Ländervergleich zur Lesekompetenz [Cross-national comparison of reading literacy]. In J. Baumert, C. Artelt, E. Klieme, M. Neubrand, M. Prenzel, U. Schiefele, W. Schneider, K.-J. Tillmann, & M. Weiß (Eds.), PISA 2000 – Die Länder der Bundesrepublik Deutschland im Vergleich (pp. 55–94). Springer Fachmedien.

Aunola, K., Leskinen, E., Onatsu-Arvilommi, T., & Nurmi, J. (2002). Three methods for studying developmental change: A case of reading skills and selfconcept. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 72, 343–364. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709902320634447

Cain, K., Oakhill, J., & Bryant, P. E. (2004). Children’s reading comprehension ability: Concurrent prediction by working memory, verbal ability, and component skills. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96, 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.1.31

Chapman, J. W., & Tunmer, W. E. (1995). Development of young children’s reading self-concepts: An examination of emerging subcomponents and their relationship with reading achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 87, 154–167. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.87.1.154

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14, 464–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9, 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

Conradi, K., Jang, B. G., & McKenna, M. C. (2014). Motivation terminology in reading research: A conceptual review. Educational Psychology Review, 26, 127–164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-013-9245-z

Cooper, B. R., Moore, J. E., Powers, C. J., Cleveland, M., & Greenberg, M. T. (2014). Patterns of early reading and social skills associated with academic success in elementary school. Early Education and Development, 25, 1248–1264. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2014.932236

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI110401

Eccles, J. S., Midgley, C., Wigfield, A., Buchanan, C. M., Reuman, D., Flanagan, C., & Mac Iver, D. (1993). Development during adolescence: The impact of stage-environment fit on young adolescents’ experiences in schools and in families. American Psychologist, 48, 90–101. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.48.2.90

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2020). From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: A developmental, social, cognitive, and sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101859

Gnambs, T., & Hanfstingl, B. (2016). The decline of academic motivation during adolescence: An accelerated longitudinal cohort analysis on the effect of psychological need satisfaction. Educational Psychology, 36, 1691–1705. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2015.1113236

Gottfried, A. E., Fleming, J. S., & Gottfried, A. W. (2001). Continuity of academic intrinsic motivation from childhood through late adolescence: A longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93, 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.93.1.3

Gottfried, A. E., Marcoulides, G. A., Gottfried, A. W., & Oliver, P. H. (2009). A latent curve model of parental motivational practices and developmental decline in math and science academic intrinsic motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101, 729–739. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015084

Graham, J. W. (2009). Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 549–576. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530

Guthrie, J. T., & Humenick, N. M. (2004). Motivating students to read: Evidence for classroom practices that increase reading motivation and achievement. In P. McCardle & V. Chhabra (Eds.), The voice of evidence in reading research (pp. 329–354). Brookes.

Guthrie, J. T., & Wigfield, A. (1999). How motivation fits into a science of reading. Scientific Studies of Reading, 3, 199–205. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532799xssr0303_1

Guthrie, J. T., & Wigfield, A. (2005). Roles of motivation and engagement in reading comprehension assessment. In S. G. Paris & S. A. Stahl (Eds.), Children’s reading comprehension and assessment (pp. 187–214). Erlbaum.

Guthrie, J. T., Wigfield, A., Metsala, J. L., & Cox, K. E. (1999). Motivational and cognitive predictors of text comprehension and reading amount. Scientific Studies of Reading, 3, 231–256. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532799xssr0303_3

Guthrie, J. T., Wigfield, A., Barbosa, P., Perencevich, K. C., Taboada, A., Davis, M. H., et al. (2004). Increasing reading comprehension and engagement through concept-oriented reading instruction. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96, 403–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.3.403

Guthrie, J. T., Hoa, L. W., Wigfield, A., Tonks, S. M., & Perencevich, K. C. (2005). From spark to fire: Can situational reading interest lead to long-term reading motivation? Reading Research and Instruction, 45, 91–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388070609558444

Guthrie, J. T., Hoa, L. W., Wigfield, A., Tonks, S. M., Humenick, N. M., & Littles, E. (2007). Reading motivation and reading comprehension growth in the later elementary years. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 32, 282–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2006.05.004

Hunt, D. E. (1975). Person-environment interaction: A challenge found wanting before it was tried. Review of Educational Research, 45(2), 209–230. https://doi.org/10.2307/1170054

Jang, Y., Lu, Z., & Cohen, A. (2015). Comparison of nested models for multiply imputed data. In R. E. Millsap, D. M. Bolt, L. A. van der Ark, & W.-C. Wang (Eds.), Quantitative psychology research (pp. 451–464). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-07503-7_28

Kintsch, W. (1998). Comprehension: A paradigm for cognition. Cambridge University Press.

Köller, O., & Baumert, J. (2008). Entwicklung schulischer Leistungen [Development of academic achievement]. In R. Oerter & L. Montada (Eds.), Entwicklungspsychologie (pp. 735–768). Beltz Verlag.

LaFontana, K. M., & Cillessen, A. H. N. (2010). Developmental changes in the priority of perceived status in childhood and adolescence. Social Development, 19, 130–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00522.x

Little, T. D., Preacher, K. J., Selig, J. P., & Card, N. A. (2007). New developments in latent variable panel analyses of longitudinal data. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 31, 357–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025407077757

Locher, F. M., Becker, S., & Pfost, M. (2019). The relation between students’ intrinsic reading motivation and book reading in recreational and school contexts. AERA Open, 5, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858419852041

Logan, S., Medford, E., & Hughes, N. (2011). The importance of intrinsic motivation for high and low ability readers’ comprehension performance. Learning and Individual Differences, 21, 124–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2010.09.011

Marsh, H. W., & Hau, K.-T. (1996). Assessing goodness of fit: Is parsimony always desirable? Journal of Experimental Education, 64, 364–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.1996.10806604

McArdle, J. J. (1988). Dynamic but structural equation modeling of repeated measures data. In J. R. Nesselroade & R. B. Cattell (Eds.), Handbook of multivariate experimental psychology (pp. 561–614). Plenum Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-0893-5_17

McElvany, N., Kortenbruck, M., & Becker, M. (2008). Lesekompetenz und Lesemotivation: Entwicklung und Mediation des Zusammenhangs durch Leseverhalten [Reading literacy and reading motivation: Their development and the mediation of their relationship by reading behavior]. Zeitschrift Für Pädagogische Psychologie, 22, 207–219. https://doi.org/10.1024/1010-0652.22.34.207

McGeown, S. P., Osborne, C., Warhurst, A., Norgate, R., & Duncan, L. G. (2016). Understanding children’s reading activities: Reading motivation, skill and child characteristics as predictors. Journal of Research in Reading, 39, 109–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9817.12060

Miyamoto, A., Murayama, K., & Lechner, C. M. (2020). The developmental trajectory of intrinsic reading motivation: Measurement invariance, group variations, and implications for reading proficiency. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101921

Möller, J., & Bonerad, E.-M. (2007). Fragebogen zur habituellen Lesemotivation [Habitual reading motivation questionnaire]. Psychologie in Erziehung Und Unterricht, 54, 259–267. https://doi.org/10.1037/t58194-000

Möller, J., & Schiefele, U. (2004). Motivationale Grundlagen der Lesekompetenz [Motivational foundations of reading literacy]. In U. Schiefele, C. Artelt, W. Schneider, & P. Stanat (Eds.), Entwicklung, Bedingungen und Förderung der Lesekompetenz: Vertiefende Analysen der PISA-2000-Daten (pp. 101–124). Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2021). Mplus user’s guide. Eighth Edition. Muthén & Muthén.

OECD. (2019). PISA 2018 results: What students know and can do. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/5f07c754-en

Park, Y. (2011). How motivational constructs interact to predict elementary students’ reading performance: Examples from attitudes and self-concept in reading. Learning and Individual Differences, 21, 347–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2011.02.009

Retelsdorf, J., Köller, O., & Möller, J. (2011). On the effects of motivation on reading performance growth in secondary school. Learning and Instruction, 21, 550–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2010.11.001

Retelsdorf, J., Becker, M., Köller, O., & Möller, J. (2012). Reading development in a tracked school system: A longitudinal study over 3 years using propensity score matching. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 82, 647–671. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.2011.02051.x

Retelsdorf, J., Köller, O., & Möller, J. (2014). Reading achievement and reading self-concept – Testing the reciprocal effects model. Learning and Instruction, 29, 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2013.07.004

Reynolds, P. L., & Symons, S. (2001). Motivational variables and children’s text search. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93, 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.93.1.14

Rychen, D. S., & Salganik, L. H. (2003). Key competencies for a successful life and a well functioning society. Hogrefe & Huber Publishers.

Schiefele, U. (1991). Interest, learning, and motivation. Educational Psychologist, 26, 299–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.1991.9653136

Schiefele, U. (1999). Interest and learning from text. Scientific Studies of Reading, 3, 257–279. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532799xssr03034

Schiefele, U., Schaffner, E., Möller, J., & Wigfield, A. (2012). Dimensions of reading motivation and their relation to reading behavior and competence. Reading Research Quarterly, 47, 427–463. https://doi.org/10.1002/RRQ.030

Shraw, G., & Lehman, S. (2001). Situational interest: A review of the literature and directions for future research. Educational Psychology Review, 13, 23–52. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009004801455

Singer, J. D., & Willett, J. B. (2003). Applied longitudinal data analysis. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195152968.001.0001

Tonks, S. M., Magliano, J. P., Schwartz, J., & Kopatich, R. D. (2021). How situational competence beliefs and task value relate to inference strategies and comprehension during reading. Learning and Individual Differences, 90, 102036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2021.102036

Unrau, N. J., & Quirk, M. (2014). Reading motivation and reading engagement: Clarifying commingled conceptions. Reading Psychology, 35, 260–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2012.684426

Widaman, K. F., & Thompson, J. S. (2003). On specifying the null model for incremental fit indices in structural equation modeling. Psychological Methods, 8, 16–37. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.8.1.16

Wigfield, A. (1997). Reading motivation: A domain-specific approach to motivation. Educational Psychologist, 32, 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3202_1

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. (1994). Children’s competence beliefs, achievement values, and general self-esteem: Change across elementary and middle school. Journal of Early Adolescence, 14, 107–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/027243169401400203

Wigfield, A., & Guthrie, J. T. (1997). Relations of children’s motivation for reading to the amount and breadth of their reading. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89, 420–432. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.89.3.420

Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., & Pintrich, P. R. (1996). Development between the ages of 11 and 25. In D. C. Berliner & R. C. Calfee (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (pp. 148–185). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Wu, W., West, S. G., & Taylor, A. B. (2009). Evaluating model fit for growth curve models: Integration of fit indices from SEM and MLM frameworks. Psychological Methods, 14, 183–201. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015858

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Christoph Lindner and Fabian Schmidt for their valuable comments on a previous version of this manuscript and Stephen McLaren for his editorial support during the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Parts of the project were funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG; Mo 648/15–1/15–3).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The research reported in this article was part of the project “Self-concept, Motivation, and Literacy: Development of Student Reading Behavior”, directed by Jens Möller (Kiel University).

Jan Retelsdorf. University of Hamburg, Von-Melle-Park 8, D-20146 Hamburg, Germany.

Current themes of research:

Text comprehension in science and mathematics. Stereotypes and judgment biases in the school context. Motivation and self-regulation for learning and performance.

Most relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education:

Cruz Neri, N., & Retelsdorf, J. (2022). The role of linguistic features in science and math comprehension and performance: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 36, 100,460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2022.100460.

Muntoni, F., Wagner, J., & Retelsdorf, J. (2021). Beware of stereotypes: Are class-mates’ stereotypes associated with students’ reading outcomes? Child Development, 92, 189–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13359.

Retelsdorf, J., Schwartz, K., & Asbrock, F. (2015). “Michael can’t read!” – Teachers’ gender stereotypes and boys’ reading self-concept. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107, 186–194. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037107.

Nadine Cruz Neri. University of Hamburg, Von-Melle-Park 8, D-20146 Hamburg, Germany and University of Bielefeld, Universitätsstraße 25, D-33615 Bielefeld.

Current themes of research:

Role of language in mathematics and science performance. Predictors of linguistic skills. Learning disorders. Diversity in the school context.

Most relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education:

Cruz Neri, N., & Retelsdorf, J. (2022). The role of linguistic features in science and math comprehension and performance: A systematic review and desiderata for future research. Educational Research Review, 100,460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2022.100460.

Cruz Neri, N., & Retelsdorf, J. (2022). Do students with specific learning disorders with impairments in reading benefit from linguistic simplification of test items in science? Exceptional Children. https://doi.org/10.1177/00144029221094049.

Cruz Neri, N., Wagner, J., & Retelsdorf, J. (2021). What makes mathematics difficult for adults? The role of reading components in solving mathematics items. Educational Psychology, 41, 1199–1219. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2021.1964438.

Jens Möller. Kiel University, Olshausenstraße 75, D-24118 Kiel, Germany.

Current themes of research:

Motivation and self-concept. Bilingual learning. Diagnostic competence.

Most relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education:

Jansen, T., Meyer, J., Wigfield, A., & Möller, J. (2022). Which student and instructional variables are most strongly related to academic motivation in K-12 education? A systematic review of meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 148, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000354.

Möller, J., Zitzmann, S., Machts, N., Helm, F., & Wolff, F. (2020). A Meta-Analysis of Relations between Achievement and Self-Perception. Review of Educational Research, 90, 376—419. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654320919354.

Möller, J. & Marsh, H. W. (2013). Dimensional comparison theory. Psychological Review, 120, 544–560. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032459.

Olaf Köller. Leibniz Institute for Science and Mathematics Education, Olshausenstraße 62, D-24118 Kiel, Germany.

Current themes of research:

Research in teaching and learning; large-scale assessments; implementing change in schools.

Most relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education:

Meyer, J. Schmidt, F. T. C, Fleckenstein, J. & Köller, O. (2023). A closer look at the domain-specific associations of openness with language achievement: Evidence on the role of intrinsic value from two large scale longitudinal studies. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 93, 113–133. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12543.

Saß, S., Schütte, K., Kampa, N. & Köller, O. (2021). Continuous time models support the reciprocal relations between academic achievement and fluid intelligence over the course of a school year. Intelligence, 87, 101,560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2021.101560.

Meyer, J., Fleckenstein, J. & Köller, O. (2019). Expectancy value interactions and academic achievement: Differential relationships with achievement measures. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 58, 58–74. j.cedpsych.2019.01.006.

Gabriel Nagy. Leibniz Institute for Science and Mathematics Education, Olshausenstraße 62, D-24118 Kiel, Germany.

Current themes of research:

National and international large-scale educational assessment. Latent variable models for aberrant response behavior in achievement tests and questionnaires. Determinants and consequences of individual transitions in the educational system.

Most relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education:

Etzel, J. M., & Nagy, G. (2021). Stability and change in vocational interest profiles and interest congruence over the course of vocational education and training. European Journal of Personality, 35, 534–556. https://doi.org/10.1177/08902070211014015.

Nagy, G., & Ulitzsch, E. (2022). A multilevel mixture IRT framework for modeling response times as predictors or indicators of response engagement in IRT models. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 82, 845–879. https://doi.org/10.1177/00131644211045351.

Nagy, G., Ulitzsch, E., & Lindner, M. A. (2022). The role of rapid guessing and test‐taking persistence in modelling test‐taking engagement. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12719.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Retelsdorf, J., Cruz Neri, N., Möller, J. et al. Correlated change in habitual and situational reading motivation. Eur J Psychol Educ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-023-00777-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-023-00777-3