Abstract

Cooperative learning (CL) refers to teaching methods in which students work in small groups to help one another learn and improve their learning outcomes. Often CL is described by five basic elements: (1) positive interdependence, (2) individual accountability, (3) promotive interaction, (4) social skills and (5) group processing. The positive effects of CL have been extensively documented. The quality of implementation, mostly determined by application of the five basic elements of CL, has been shown to be significantly related to the effectiveness of the methods. However, due to the complex demands that designing CL sequences places on teachers, the question of how and why they implement CL methods is not trivial. The present study used an explanatory mixed methods design with sequential phases (quantitative–qualitative) to investigate the implementation of CL in school practice. A survey, structured interviews with teachers and classroom observations rated on an observation scale including indicators of the basic elements of CL were used to gather data in a total of 49 German classrooms. Results show that the implementation quality of CL lessons was rather low. Only 7% of the observed teachers implemented the basic elements. Even group goals and individual accountability, the two most important elements of CL, were implemented in only 17% of the lessons observed. Survey results indicated that implementation quality is related to teachers’ evaluation of CL with regard to its appropriateness for different learning goals (r = .40*) and diverse students (r = .36*). Qualitative analysis of the teacher interviews analysed by thematic coding showed differences between teachers with high and low implementation quality regarding their beliefs. Teachers with high implementation quality see more value in social learning processes and feel more responsible for the success of CL. The results show a theory–practice gap and point to the relevance of beliefs for CL implementation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The effectiveness of cooperative learning (CL) has been extensively documented using cognitive and social criteria of school learning success (Johnson et al., 2000; Kyndt et al., 2013; Slavin, 1995). The effectiveness of CL is significantly related to the quality of its implementation in school practice (Slavin, 1983; Veenman et al., 2000, 2002; Supanc et al., 2017). However, previous studies have indicated that teachers find the implementation of CL challenging and that the quality of implementation is often low (Buchs et al., 2017; Gillies & Boyle, 2010). In order to develop appropriate support for teachers in school practice, an in-depth investigation of CL implementation and the conditions for success is needed. Therefore, the present study investigates this using a mixed methods design.

Cooperative learning—basic elements and effectiveness

CL refers to teaching methods in which students work in small groups to help one another learn and improve their learning outcomes (Johnson et al., 2014; Slavin, 1995). Both Slavin (1995) and Johnson and Johnson (1989) identify basic elements that should be considered when implementing CL in order to ensure effectiveness and avoid negative side effects like free riding. The most central of these are (1) positive interdependence and (2) individual accountability. Positive interdependence is the realisation among group members that they can only be successful if the other group members are successful. This can be established in various ways such as through shared resources, assigned roles or a common goal. Individual accountability is when each group member has clear identifiable responsibility for their own work as well as for the whole group and group outcome. This can be accomplished by allocating subtasks to the group members or adding up the individual performances of all students for the group result. Johnson and Johnson (1989) also identify the features (3) promotive interaction, (4) social skills and (5) group processing as inherent characteristics of CL. Promotive interaction is when students promote each other’s success by praising, motivating, helping and correcting each other. In the process, they provide explanations of facts and tasks, discuss concepts, challenge each other and exchange knowledge. This requires social skills, which are also enhanced through CL activities. In group processing, group members reflect on which actions are helpful in terms of working together, achieving common goals and deciding which behaviours to continue or change. A higher degree of implementation of these five basic elements seems to be positively related to group members’ learning (Supanc et al., 2017; Veenman et al., 2002).

The positive effects of CL on learning performance in several subjects as well as on social and motivational outcomes (cooperative skills, communication skills, self-concept) have been repeatedly confirmed in meta-analyses (Ginsburg-Block et al., 2006; Johnson et al., 2000; Kyndt et al., 2013; Rohrbeck et al., 2003; Slavin, 1995).

Implementation of cooperative learning

Studies have reported on the various challenges that teachers encounter when implementing CL, such as lack of time for preparation or missing social skills of students (Abramczyk & Jurkowski, 2020; Gillies & Boyle, 2010; Völlinger et al., 2018). This raises the question of how teachers deal with these challenges and achieve implementation quality to ensure effectiveness. In most studies, the implementation quality of CL is determined by application of the basic elements. When asked about their implementation, teachers indicated that they very often form groups (Antil et al., 1998; McManus & Gettinger, 1996), but rarely incorporate an interdependent reward structure (McManus & Gettinger, 1996). Antil et al. (1998) report that only one of the 21 teachers they interviewed implemented all five basic elements. Five of the teachers reported implementing the two characteristics of individual accountability and positive interdependence.Völlinger et al. (2018) surveyed 76 German secondary school teachers by questionnaire on the quality of implementation of CL. The resulting mean score of 2.38 (SD = 0.62, with a possible range of 0 to 4) shows that in this sample teachers also did not report full implementation of the basic elements of CL.

Although classroom observations can provide more detailed and valid insights into the implementation quality of CL, observational studies are rare. Veldman et al. (2020) analysed video recordings of CL implementation by teachers who had received in-service training, with a focus on the role of teachers in first- and second-grade classrooms. Similarly, Veenman et al. (2000) observed the implementation quality of teachers in first- to eighth-grade classrooms. Both studies conducted with Dutch teachers reported a low quality of implementation, defined as a lack of basic elements of CL in the teaching practices of the majority of teachers. However, some teachers were able to effectively implement high-quality CL. This raises the question of what factors contribute to the differences in implementation quality.

Teacher evaluations of and beliefs about cooperative learning

There is evidence that teachers’ beliefs influence the quality of implementation: Teachers’ self-efficacy has consistently been shown to be relevant for the implementation of CL (Völlinger et al., 2018). Teachers also differ in their evaluation of CL. In some studies, teachers reported that academic and social learning goals are achieved through CL (e.g. Antil et al., 1998). In others, teachers felt that CL was particularly appropriate for higher-achieving and older students, while implementation in heterogeneous classes was seen as problematic (Abramczyk & Jurkowski, 2020; Völlinger et al., 2018), despite empirical evidence to the contrary (Büttner al., 2012; Kyndt et al., 2013). Teachers with high implementation quality seemed to have a more positive view of CL (Abramczyk & Jurkowski, 2020; Saborit et al., 2016; Veldman et al., 2020; Webb, 2009).

As one of the very few studies explicitly comparing teachers with high and low implementation quality with regard to their perspectives on the implementation and challenges of CL, Veldman et al. (2020) concluded that teachers with different implementation of CL also differed in how they explicitly taught and modelled cooperative behaviours for effective group work. Teachers with high implementation quality were more convinced of the value of CL. The authors also found that negative attitudes are often based on teachers’ practical experiences after unsuccessful implementation attempts, which can result in a negative spiral (Kyndt et al., 2013). In order to avoid this, more research is needed to shed light on the conditions required for high-quality implementation of CL in school practice. In addition, teacher evaluations of and beliefs about CL should be taken into consideration. Accordingly, we intend to address this research gap in the present study.

Aim of the present study

The aim of the present study is to obtain a more detailed picture of the implementation quality of CL in German classrooms. The central research questions to be answered are the following:

-

(1)

How is the implementation quality of CL?

What basic elements of CL—as indicators of implementation quality—are visible in the lessons? How do teachers implement them?

-

(2)

Which teacher beliefs are connected with implementation quality?

How do teachers rate the appropriateness of CL for different learning goals and diverse students and their own effectiveness in implementing CL? How are these evaluations related to their implementation quality?

-

(3)

What are the differences between teachers with high vs. low implementation quality?

How do these teachers differ in their perspectives on CL, its implementation and the challenges involved?

Method

Sample and study design

The study took place at two different universities in Germany from 2018 to 2020. We used an explanatory mixed methods design with sequential phases (quantitative–qualitative; Ponce & Pagán-Maldonado, 2015) to analyse and explain the implementation of CL in German classrooms. In the first phase, we collected and analysed quantitative data on the implementation of and beliefs about CL (research questions 1 and 2). To shed light on how teachers with different implementation qualities differ in their perspectives on CL (research question 3), we carried out a qualitative analysis of teacher interviews.

The teachers in the sample were recruited by student teachers in the context of their university courses on CL. Participation in the study was voluntary. All participants gave written informed consent to participate in the study and to use the data. Ethical approval was not required, as the study is non-interventional. A total of 49 teachers completed the questionnaire. Additionally, we observed 30 teachers during CL lessons (5 video recordings and 25 classroom observations),Footnote 116 of whom also completed the questionnaire and gave an interview. Teachers chose the subject and time of the observation themselves but were instructed to use CL in the observed lessons. Observations without a group work phase were excluded from the sample. Overall, participating teachers taught 1st through 12th grade students in several subject areas. Their teaching experience ranged from 1 to 30 years (M = 10.55). The sample and subsample are described in Table 1.

Quantitative phase: 1. questionnaire

The survey of demographic data (see Table 1) was followed by scales on teachers’ evaluation of the appropriateness of CL for different learning goals and diverse students as well as their beliefs (self-efficacy) and average implementation quality in their regular practice.

Appropriateness for different learning goals and diverse students

Learning goals. Using 7 items, teachers were asked about their learning goals in using CL (adapted from Völlinger et al., 2018). The given target categories were improvement of academic performance, strengthening of class cohesion, training of social skills, increase of motivation, building of self-confidence, promotion of independence and teaching of values. All items were answered on a 4-point scale ranging from ‘not at all true’ to ‘absolutely true’. Reliability was acceptable (α = 0.598).

Suitability for diverse students

The teachers were also asked about their assessment of which students CL was particularly suitable for (adapted from Völlinger et al., 2018). They rated the suitability of CL for lower-performing students, middle-performing students, higher-performing students, students with difficult social behaviour, students with language deficits, and heterogeneous groups of students on a 4-point scale (0 = ‘not at all true’, 1 = ‘rather not true’, 2 = ‘rather true’, 3 = ‘absolutely true’). Reliability of the scale was satisfactory (α = 0.740).

Although teachers could also focus on specific goals and student groups without addressing the others, the scale was used to evaluate teachers’ commitment to CL as a relevant belief for implementation (Völlinger et al., 2018).

Teachers’ self-efficacy for cooperative learning

With regard to self-efficacy for implementation of CL, 6 items were included in the questionnaire, which were also answered on a 4-point scale ranging from ‘not at all true’ to ‘absolutely true’. A sample item is ‘I am confident in encouraging students of different backgrounds to support each other’ (Meschede & Hardy, 2020). One item was excluded from the evaluation because it had a selectivity below 0.3 (Moosbrugger & Kelava, 2007). The resulting 5-item scale had a satisfactory internal consistency of Cronbach’s alpha = 0.777.

Reported implementation quality

Using 28 items with a 4-point response scale ranging from ‘not at all true’ to ‘absolutely true’, teachers provided information about implementation quality with regard to indicators of the five basic elements in a typical CL phase in their classroom (adapted from Völlinger et al., 2018) . A sample item is ‘In a typical CL lesson I make sure all students have a important role in their group’. Although 6 items (expert topics, group size, discussions, group goal, competition, group identity) had a selectivity below 0.3 and 1 item had a high item difficulty (group reward), we decided to include them in the analysis because of their content relevance. The internal consistency of the scale can be rated as good with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.869.

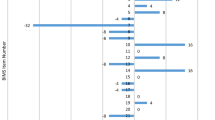

Quantitative phase: 2. observation scale

Our observation scale was constructed parallel to the questionnaire on implementation quality but focussed only on the observable indicators of the basic elements. It consisted of 11 items (see Table 2 and Supplement). In each class, the items were rated by three project members along a dichotomous scale (0 for no application of the instructional behaviour, 1 for application of the instructional behaviour). Prior to the ratings in the schools, the three observers participated in a training programme of about 4 h and received a manual with a detailed description of all items, examples and critical indicators. If one of the items for a basic element was rated as present, the basic element was considered implemented. All observations were conducted by a minimum of two observers to check interrater agreement using Krippendorff’s alpha.Footnote 2In some cases, this calculation resulted in an error due to missing variation. In these cases, interrater agreement was 100%. Overall, interrater agreements ranged from acceptable to very good (see Table 2).

Qualitative phase: interviews

Sixteen teachers took part in semi-structured interviews (questions adapted from Gillies & Boyle, 2010) right after the implementation of CL to make sure the reported perspective referred to the observed lesson. Teachers were asked by the student teachers about their CL practices, how they dealt with challenges concerning CL, what they did to make CL work and their satisfaction with the implementation with regard to the observed lesson. The interviews took 9 to 14 min, they were audio-recorded and transcribed for analyses. For a better understanding of implementation differences, we analysed the interviews of the two teachers who implemented all the basic elements of CL in their lessons and compared them with the interviews of two teachers who did not implement any of the basic elements of CL. These two contrasting pairs were then matched according to subject and grade level. This resulted in one primary school match for German lessons and one secondary school (Gymnasium) match (10th and 12th grade) for lessons in mathematics and geography. The sample is shown in Table 3.

We identified and analysed group-specific similarities and differences using thematic coding (Strauss, 1991, modified by Flick, 2016). This method allowed us to compare the perspectives of groups on a specific subject matter or process. In the first step, we carried out case-related analyses by a short description and typical statements. In the second step, we analysed the thematic categories of each interview and compared them between cases. This resulted in a thematic structure of groups, which was used for comparison.

Results

Observed implementation quality

Only 2 of the participating 30 teachers implemented all four basic elements in the observed lessons, while 11 did not implement any of the elements. Twelve teachers implemented only some of the features: 5 teachers implemented one element, 6 teachers implemented two elements and 6 implemented three elements. See Table 4 for an overview of the implementation of the basic elements.

In order to achieve positive interdependence, most of the teachers (8) assigned different roles to group members. Some of them used goal interdependency (6), while reward interdependency (1) and resource interdependency (3) were rarely observed. For individual accountability, teachers implemented task accountability (8) more often than reward accountability (3) or the assessment of individual learning gains (1). Promotive interaction was realised in 7 classes through the exchange of information or knowledge and in 3 classes through the exchange of opinions. Group processing was realised by implementing a structured reflection phase (9).

Teachers’ evaluations, beliefs and reports

Appropriateness for different learning goals and diverse students

On average, the teachers reported an appropriateness of M = 3.26 (SD = 0.36) for different learning goals (possible range 1 to 4). More than 90% of teachers rated CL appropriate for the training of social skills, promotion of independence and teaching of values. In addition, more than 80% reported to use CL for strengthening of class cohesion and to increase motivation. Over 20% of the teachers negated the appropriateness of CL for improving academic performance and building self-confidence (see Table 5).

The mean reported suitability of CL for diverse students was M = 3.10 (SD = 0.45). More than 90% of teachers agreed on the suitability of CL for intermediate students and heterogeneous learning groups. Over 80% of teachers also (rather) agreed that CL was suitable for both low- and high-performing students as well as those with language deficits. For students with difficult social behaviour, only 53.2% of teachers agreed that cooperative methods were suitable for this group.

Teachers’ self-efficacy for cooperative learning

On average, the teachers reported a self-efficacy of M = 3.43 (SD = 0.39), which was at the upper value range with a possible maximum value of 4.

Reported implementation quality

The mean reported implementation quality in regular CL lessons was M = 2.86 (SD = 0.34), with a minimum of 2.21 and a maximum value of 3.64 (possible range 1 to 4), which means that teachers rated their implementation quality as rather high.Footnote 3

Relationships between questionnaire variables (Table 6)

To compute the correlations, sum scores were calculated for the learning goals and suitability of CL. A higher sum value can be interpreted as meaning that CL was assessed as suitable for different learning goals and students, which results in more application possibilities.

Self-reported implementation quality correlates positively with self-efficacy for CL (p < 0.001) and suitability of CL (p = 0.019). Furthermore, implementation quality meaningfully correlates with the learning goals of CL (p = 0.009).

Comparison of teachers with high and low implementation quality

Results of the qualitative analysis with regard to the perspectives on CL of teachers with high vs. low implementation quality show a thematic pattern with group differences for the value of social learning and responsibility for the success of CL.

Value of the social learning process

The most noticeable difference between the perspectives of teachers with high and low implementation quality of CL was their perception of the value of social learning processes. Teachers with high implementation of CL elements emphasised the importance of exchanging information or making use of the group members’ strengths. Their primary goal in implementing CL was the students’ experience and recognition of the intrinsic value of cooperation, which they viewed as a key competence and basis for learning. A typical statement regarding this perspective was the following: ‘And it became so clear to me that, that is exactly what is missing in school and to work on it is very important. And that this cooperation is important and that we also have to prepare them for what will come later. And that competence, that they learn through this method, um, will be important in all areas in the future’ (Case 2). In both cases with full implementation, the teachers took the time to develop social competencies during their lessons. In this context, they said that reflection on group processes is very important: ‘I think it’s also important to reflect on the cooperative process and to make it clear to the pupils that the learning process takes place WITHIN the group’ (Case 1).

In contrast, the teachers who did not implement the basic elements described the social processes during CL as a kind of ‘sideshow’: ‘Pff… inevitably through the group work phase, a social competence is then always necessary somehow’ (Case 3). Thus, they did not devote time to teaching the necessary skills or facilitating reflection on group processes. ‘So, there was no reflection on group processes, nor did it take place in the other lessons. So, I really didn’t have the time for that either’ (Case 4). Both of the teachers with low implementation quality described academic goals as paramount and based their evaluation of the observed lesson accordingly. For example, in Case 3, the teacher felt that the lessons were a success because the class had achieved the academic goals even though the students did not work together in most of the groups.

Responsibility and effort for success

Although CL is described as a student-centred approach, teachers with high implementation of CL elements see themselves as responsible for successful group processes. A typical statement was ‘And as a teacher you have to prepare the lesson of course, but you also have to be there for the students and see what is happening? What do the children need now?’ (Case 2). Both cases see problems in the CL process or students’ behaviour as an indication for the teacher to make necessary changes (e.g. to the group constellation or role assignment). In contrast, the teachers with low implementation take necessary competencies for granted and place the blame for failure on the pupils as the following statement shows: ‘And as you could see in one of the groups, they couldn’t talk to each other at all. It was actually due to the students themselves. But I didn’t include that in the plan or in the planning process in any way beforehand’ (Case 3). The teachers did not feel the need to take responsibility for changing the situation or supporting the CL process.

Discussion

In the present study, we used a sequential mixed methods design to evaluate implementation quality and teacher beliefs regarding CL. In addition, we also compared the perspectives of teachers with high and low implementation quality in German classrooms. The results of classroom observations show that the implementation quality of CL was rather low, with only two teachers implementing all the basic elements and more than one-third not implementing any CL elements at all. These findings complement the paucity of observational studies on the implementation quality of CL in the Netherlands (Veenman et al., 2000; Veldman et al., 2020). Since implementation of the basic elements of CL was shown to be significant for the effectiveness of the methods (Slavin, 1983; Supanc et al., 2017; Veenman et al., 2002), it is questionable whether the positive effects of CL could unfold in the observed lessons. To gain a deeper insight, we also observed how teachers implemented the basic elements. The results indicate that there was very limited use of reward and assessment strategies to ensure the implementation of basic elements (e.g. reward accountability). This could be attributed to the belief among some teachers that promoting cooperation is not compatible with reward structures (Vadasy et al., 1997). Therefore, this factor should be considered in future teacher education programmes on CL.

Similar to previous studies, our analyses indicate that teachers’ beliefs and evaluations are relevant for implementation quality. Teachers who have high self-efficacy use CL to address many learning goals (see also Abramczyk & Jurkowski, 2020; Völlinger et al., 2018), see it as appropriate for a variety of students and implement it at a higher quality and/or vice versa. Since we calculated correlations, we cannot conclude the latter from our study. However, it has been shown that a lack of implementation quality can lead to negative beliefs and frustration in teachers and students and thus to a negative spiral (Veldman et al., 2020) inhibiting future implementation of CL.

To gain a better understanding of the differences in implementation quality and the conditions for success, we conducted qualitative analyses of interview data to compare teachers with high and low implementation quality with regard to their perspectives on CL. Our results indicate that teachers with high implementation quality see more value in social competencies and feel more responsible for the success of CL processes. They are highly motivated to implement CL despite challenges. Thus, it appears that these teachers see CL as an important process of and for learning instead of a methodological ‘add-on’. In contrast, the teachers with low implementation quality of CL place more emphasis on academic goals and see the training of and reflection on social skills as too time-consuming. This is supported by the observational data, which show that group processing in particular was rarely implemented. However, group reflection processes are important for fostering long-term social skills (Archer-Kath et al., 1994). Blatchford et al. (2003) concluded that curriculum demands can result in time-related stress, which hinders teachers from implementing CL. Furthermore, teachers with low implementation quality in our study tend to attribute difficulties in cooperation to the students instead of taking responsibility for training and supporting social processes. These teachers seem to lack professional beliefs and motivational orientations associated with models of professional competence (Kunter et al., 2013). Our results on the differences between teachers with high and low implementation regarding the importance given to social processes during CL are similar to those of Veldman et al. (2020) even though the sample in their study had received in-service training in CL prior to implementation. Thus, the underlying beliefs seem to be resistant to change. At the same time, they play a key role in facilitating implementation quality and the success of CL.

In addition to the research focus of this article, another finding was the discrepancy between teachers’ self-reported implementation quality and the results obtained from observations. One possible reason for these differences is that teachers may have overestimated the quality of their implementation due to a lack of knowledge about the basic elements of CL. This could be attributed to the fact that most of the participants had not received CL training. Hennessey and Dionigi (2013) emphasise the importance of teachers’ knowledge in assessing CL. Furthermore, the results of the qualitative analyses could be crucial in this context. When asked about their implementation of basic elements, teachers with low implementation felt that responsibility for the success of CL rested with the students. This may have led to the belief that they were implementing CL effectively, but the students were not. As a result, they rated their implementation of elements rather highly despite the lack of student engagement. These findings highlight the need for further research to explore the differences in perspectives between teachers and observers.

Overall, our results point to the relevance of teachers’ beliefs and motivational orientations for CL implementation. Therefore, our findings are consistent with models of teachers’ professional competence that emphasise the importance of knowledge, professional beliefs, motivational orientations and self-regulation for ensuring the quality of instruction (Kunter et al., 2013).

Limitations

An important limitation of the present study is the sample examined. For organisational reasons, it was not possible to visit and interview all the teachers who participated in the survey in the classroom and to survey all teachers we visited. Consequently, there are different sample sizes for the survey and observational data. Since participating teachers were mostly recruited through university students, it is possible and likely that those who were willing to open their classrooms for observation constituted a selective sample of teachers with certain personal characteristics (e.g. higher teaching self-efficacy). This limits the transferability of the results to other samples.

Since the focus of our study was teachers’ implementation of CL, we do not have information on the quality of students’ implementation of CL when working together in groups. Therefore, in order to obtain a complete picture of CL implementation in the classroom, future studies should include the students’ perspective and observe their cooperation.

Conclusion and implications

Our study shows a theory–practice gap concerning CL. Despite being well-founded theoretically and empirically, most teachers do not implement the basic elements of CL at a high level. In addition to previous studies, the mixed methods design allowed a deeper understanding of central starting points for interventions. The results of the present study underscore that simply teaching knowledge in teacher education and in-service training is probably not enough to foster implementation of CL in schools. Teachers’ beliefs also need to be addressed. Pre-service and in-service teacher training should therefore focus on the great importance of the responsibility of teachers in promoting and valuing social learning processes and knowledge transfer. Taken together the results of our study suggest that future interventions should address all dimensions of teachers’ professional competence to avoid a spiral of negative beliefs and unsuccessful implementation of CL.

Notes

Five videotaped CL lessons from (project name and institution, anonymised for peer-review) (source: https://unterrichtsvideos.net/metaportal/) were included in the study in order to obtain additional observational data, all of which were found using the keyword ‘CL’. Since these videos were also recorded for teacher education purposes, partly within the same seminar context as the observations, no differences in outcomes were anticipated. However, these teachers were not required to complete a questionnaire or give an interview.

Krippendorff’s alpha was chosen as the measure of interrater reliability because of its flexibility. It can be used with two or more raters and is reliable even if there are missing values or the scale is not nominal (Zapf et al., 2016).

In contrast to the scores obtained in the observations, teachers rated their implementation quality in regular CL lessons rather high, there was no correlation between these two scales, r = 361, p = .17 (N = 16). Since it was not the aim of this study to compare perspectives, we do not elaborate further on this difference.

References

Abramczyk, A., & Jurkowski, S. (2020). Cooperative learning as an evidence-based teaching strategy: What teachers know, believe, and how they use it. Journal of Education for Teaching, 46(3), 296–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2020.1733402

Antil, L. R., Jenkins, J. R., Wayne, S. K., & Vadasy, P. F. (1998). Cooperative learning: Prevalence, conceptualizations, and the relation between research and practice. American Educational Research Journal, 35(3), 419–454. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312035003419

Archer-Kath, J., Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1994). Individual versus group feedback in cooperative groups. The Journal of Social Psychology, 134(5), 681–694. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1994.9922999

Blatchford, P., Kutnick, P., Baines, E., & Galton, M. (2003). Toward a social pedagogy of classroom group work. International Journal of Educational Research, 39(1–2), 153–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-0355(03)00078-8

Buchs, C., Filippou, D., Pulfrey, C., & Volpé, Y. (2017). Challenges for cooperative learning implementation: Reports from elementary school teachers. Journal of Education for Teaching, 43(3), 296–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2017.1321673

Büttner, G., Warwas, J., & Adl-Amini, K. (2012). Kooperatives Lernen und Peer Tutoring im inklusiven Unterricht [Cooperative Learning and Peer Tutoring in inclusive classrooms]. Zeitschrift für Inklusion, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:5877

Flick, U. (2016). Qualitative Sozialforschung: Eine Einführung (7th ed.). [Qualitative Social Science Research. An Introduction]. Rowohlt Taschenbuch.

Gillies, R. M., & Boyle, M. (2010). Teachers’ reflections on cooperative learning: Issues of implementation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(4), 933–940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.10.034

Ginsburg-Block, M. D., Rohrbeck, C. A., & Fantuzzo, J. W. (2006). A meta-analytic review of social, self-concept, and behavioral outcomes of peer-assisted learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(4), 732–749.

Hennessey, A., & Dionigi, R. A. (2013). Implementing cooperative learning in Australian primary schools: Generalist teachers’ perspectives. Issues in Educational Research, 23(1), 52–68.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1989). Cooperation and competition: Theory and research. Interaction Book Company.

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Smith, K. A. (2014). Cooperative learning: improving university instruction by basing practice on validated theory [Special focus issue: Small-group learning in higher education— Cooperative, collaborative, problem-based, and team-based learning]. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 25(3-4), 85–118.

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Stanne, M. B. (2000). Cooperative learning methods: A meta-analysis. University of Minnesota Retrieved November 23rd, 2023, from https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Cooperative-learningmethods%3A-A-meta-analysis.-Johnson-Johnson/93e997fd0e883cf7cceb3b1b612096c27aa40f90

Kunter, M., Klusmann, U., Baumert, J., Richter, D., Voss, T., & Hachfeld, A. (2013). Professional competence of teachers: Effects on instructional quality and student development. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(3), 805–820. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032583

Kyndt, E., Raes, E., Lismont, B., Timmers, F., Cascallar, E., & Dochy, F. (2013). A meta-analysis of the effects of face-to-face cooperative learning: Do recent studies falsify or verify earlier findings? Educational Research Review, 10, 133–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2013.02.002

McManus, S., & Gettinger, M. (1996). Teacher and student evaluations of cooperative learning and observed interactive behaviors. The Journal of Educational Research, 90(1), 13–22.

Meschede, N., & Hardy, I. (2020). “Selbstwirksamkeitserwartungen von Lehramtsstudierenden zum adaptiven Unterrichten in heterogenen Lerngruppen“ [Preservice teachers’ self-efficacy of adaptive teaching in heterogeneous classrooms]. Zeitschrift Für Erziehungswissenschaft, 23(3), 565–589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-020-00949-7

Moosbrugger, H., & Kelava, A. (Eds.). (2007). Testtheorie und Fragebogenkonstruktion [Test theory and questionnaire construction]. Springer.

Ponce, O. A., & Pagán-Maldonado, N. (2015). Mixed methods research in education: Capturing the complexity of the profession. International Journal of Educational Excellence, 1(1), 111–135. https://doi.org/10.18562/IJEE.2015.0005

Rohrbeck, C. A., Ginsburg-Block, M. D., Fantuzzo, J. W., & Miller, T. R. (2003). Peer-assisted learning interventions with elementary school students: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(2), 240–257.

Saborit, J. A. P., Fernández-Río, J., Cecchini Estrada, J. A., Méndez-Giménez, A., & Alonso, D. M. (2016). Teachers’ attitude and perception towards cooperative learning implementation: Influence of continuing training. Teaching and Teacher Education, 59, 438–445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.07.020

Slavin, R. E. (1983). When does cooperative learning increase student achievement? Psychological Bulletin, 94(3), 429–445. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.94.3.429

Slavin, R. E. (1995). Cooperative learning: Theory, research, and practice (2nd ed.). Allyn and Bacon.

Slavin, R. E. (2010). Co-operative learning: What makes group work work? In The nature of learning: using research to inspire practice (pp. 161–178). Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264086487-9-en

Strauss, A. L. (1991). Grundlagen qualitativer Sozialforschung. Datenanalyse und Theoriebildung in der empirischen soziologischen Forschung. [Fundamentals of qualitative social research: Data analysis and theory formation in empirical sociological research]. Fink.

Supanc, M., Völlinger, V. A., & Brunstein, J. C. (2017). High-structure versus low-structure cooperative learning in introductory psychology classes for student teachers: Effects on conceptual knowledge, self-perceived competence, and subjective task values. Learning and Instruction, 50, 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2017.03.006

Vadasy, P. F., Jenkins, J. R., Antil, L. R., Phillips, N. B., & Pool, K. (1997). The research-to-practice ball game: Classwide peer tutoring and teacher interest, implementation, and modifications. Remedial and Special Education, 18(3), 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/074193259701800303

Veenman, S., Kenter, B., & Post, K. (2000). Cooperative learning in Dutch primary classrooms. Educational Studies, 26(3), 281–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055690050137114

Veenman, S., van Benthum, N., Bootsma, D., van Dieren, J., & van der Kemp, N. (2002). Cooperative learning and teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18(1), 87–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00052-X

Veldman, M. A., van Kuijk, M. F., Doolaard, S., & Bosker, R. J. (2020). The proof of the pudding is in the eating? Implementation of cooperative learning: Differences in teachers’ attitudes and beliefs. Teachers and Teaching, 26(1), 103–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2020.1740197

Völlinger, V. A., Supanc, M., & Brunstein, J. C. (2018). Kooperatives Lernen in der Sekundarstufe: Häufigkeit, Qualität und Bedingungen des Einsatzes aus der Perspektive der Lehrkraft [Cooperative learning in secondary school: Frequency, quality and conditions for implementation from the teacher’s View]. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 21(1), 159–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-017-0764-0

Webb, N. M. (2009). The teacher’s role in promoting collaborative dialogue in the classroom. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 79, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709908X380772

Zapf, A., Castell, S., Morawietz, L., & Karch, A. (2016). Measuring inter-rater reliability for nominal data: Which coefficients and confidence intervals are appropriate? BMC Medical Research Methodology, 16, 93. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-016-0200-9

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was supported by the Goethe Research Academy for Early Career Researchers (GRADE) under the grant ‘Fokus Linie A/B 2019.’

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Katja Adl-Amini, Department of Human Sciences, Technical University Darmstadt, Alexanderstraße 6, D-64283 Darmstadt, Germany. katja.adl-amini@tu-darmstadt.de

Current themes of research:.

Peer-assisted learning. Cooperative learning in school and university education. Dissemination of cooperative learning settings in schools. Formative assessment and individualized instruction. Reflective practice in teacher education. Simulation games in teacher education.

Most relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education:.

Moos, M., Adl-Amini, K. & Hardy, I. (2022): Kooperative Unterrichtsplanung von angehenden Regel- und Förderschullehrkräften – Ein Seminarkonzept [Collaborative lesson planning of special needs teachers and mainstream classroom teachers–a concept for pre-service teacher education] k:ON -Kölner Online Journal für Lehrer*innenbildung, 5(1), S. 111-130. https://doi.org/10.18716/ojs/kON/2022.0.6.

Adl-Amini, K. 2018. Tutorielles Lernen im naturwissenschaftlichen Sachunterricht der Grundschule. Umsetzung und Wirkung [Peer tutoring in primary science classrooms–Implementation and effectiveness]. Münster: Waxmann.

Hondrich, A. L., Hertel, S., Adl-Amini, K., & Klieme, E. (2015). Implementing curriculum-embedded formative assessment in primary school science classrooms. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 23(3), 353-376. doi: org/10.1080/0969594X.2015.1049113 .

Vanessa A. Völlinger. Psychology, University of Education, Kunzenweg 21, D-79100 Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany. E-Mail: Vanessa.Voellinger@ph-freiburg.de.

Current themes of research:.

Promotion of reading literacy. Cooperative learning in schools and universities. Dissemination of cooperative learning settings in schools. Single-case intervention research. Peer-assisted learning.

Most relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education:.

Völlinger, V. A., Lubbe, D. & Stein, L.-K (2023). A quasi-experimental study of a peer-assisted strategy-based reading intervention in elementary school. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 73, 102180. doi: org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2023.102180 .

Völlinger, V. A., Supanc, M. & Brunstein, J. C. (2018). Examining between-group and within-group effects of a peer-assisted reading strategies intervention. Psychology in the Schools, 55, 573-589. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22121.

Völlinger, V. A., Supanc, M., & Brunstein, J. C. (2018). Kooperatives Lernen in der Sekundarstufe: Häufigkeit, Qualität und Bedingungen des Einsatzes aus der Perspektive der Lehrkraft. [Cooperative learning in secondary school: Frequency, quality and conditions of implementation from the teacher’s view]. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 21, 159-176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-017-0764-0.

Agnes Eckart. Educational Psychology, Justus-Liebig University of Giessen, Otto-Behaghel-Strasse 10F, D-35394 Giessen, Germany. E-Mail: Agnes.B.Eckart@psychol.uni-giessen.de.

Current themes of research:.

Cooperative learning in schools and universities. Video analysis of student interactions. Promoting the use of learning strategies and researching emotional and metacognitive processes in cooperative learning settings.

Most relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education:.

Völlinger, V. A., Stein, L. K., & Eckart, A. (2022). Quantität und Qualität des Strategieeinsatzes von Grundschülerinnen und Grundschülern in reziproken Lesegruppen [Quantity and quality of elementary school students’ strategy use in reciprocal reading groups]. Zeitschrift für Grundschulforschung, 15(2), 361-378.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Adl-Amini, K., Völlinger, V.A. & Eckart, A. Implementation quality of cooperative learning and teacher beliefs—a mixed methods study. Eur J Psychol Educ (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-023-00769-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-023-00769-3