Abstract

Given the high number of refugee children and adolescents around the globe, it is critical to determine conditions that foster their adaptation in the receiving country. This study investigated the psychological adaptation of recently arrived adolescent refugees in Germany. We focused on whether psychological adaptation reflects the organizational approach taken by the school that refugee adolescents initially attended. School is an important context for the development and acculturation of young refugees. As in other European countries, the schooling of refugee adolescents in Germany is organized in different models: separate instruction in newcomer classes, direct immersion in regular classes, and mixed approaches. To answer our research questions, we used self-reported data from 700 refugee adolescents (12-, 14-, and 17-year-olds) in a representative survey of refugees in Germany. As indicators of their psychological adaptation, we analyzed their sense of school belonging, their emotional and behavioral problems, and their life satisfaction. Comparing them to non-refugee peers, the refugee adolescents showed similar levels of psychological adaptation, and an even higher level in the case of school belonging. Multiple regression analyses provide limited support for the assumed advantage of the mixed school organizational model: While students who initially attended a mixed approach reported higher levels of school belonging than those in other models, no differences emerged on the other indicators. We discuss the implications of our findings for the schooling of newly arrived refugees.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Psychological adaptation of young refugees and the role of different school organizational models

In the twenty-first century, there is a global increase in forced migration due to war and social unrest. Germany, alongside several EU member states, gave shelter to a large number of forcibly displaced people and still hosts many refugees (UNHCR, 2020). Over one-third of asylum requests in Germany between 2013 and 2016 concerned minors (BAMF, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017), resulting in about half a million refugee children and adolescents who had to be included in the educational system (Mediendienst Integration, 2017).

Psychological adaptation, defined as immigrants’ affective response to acculturation, has been identified as one of two major categories of intercultural adaptation (Ward, 1996, 2001), including among adolescents (Berry et al., 2006; Sam et al., 2006). Due to various obstacles, adolescents with a refugee background face special challenges in their psychological adaptation (Buchanan et al., 2018; Fazel & Stein, 2002; Fazel et al., 2012). While many studies have focused on the role of pre-migration experiences, such as trauma and loss (e.g., Hunkler & Khourshed, 2020; Lustig et al., 2004; Steel et al., 2009), others emphasized the need to pay attention to the conditions in the receiving society (e.g., Matthews, 2008), since these can be modified and also play a vital role (Correa-Velez et al., 2010; Fazel et al., 2012; Porter & Haslam, 2005; Schachner et al., 2018; Zwi et al., 2018). In this study, we focused on school as a key acculturative context for refugee adolescents (Suárez-Orozco et al., 2018; Vedder & Horenczyk, 2006). In school, adolescents do not only acquire academic skills; they also familiarize with the norms and values of the receiving society (Vedder & Horenczyk, 2006) and develop socially and emotionally (Roeser et al., 2000).

There are different approaches to school newly arrived immigrant students, including a temporary separate provision in newcomer classes or a direct immersion in regular classes. The evaluation of such programs has been identified as one of the most important areas of immigrant and refugee research (McNeely et al., 2017). However, empirical evidence in this area is scarce, and there is an ongoing controversy on how these different school organizational models affect the school adaptation of refugee students (see “The role of school organizational models in the adaptation of newly arrived students” section). The present article addresses this issue by drawing on a large representative sample of recently arrived refugees in Germany. In a first step, our study investigates how well recently arrived refugee adolescents are adjusted in terms of their psychological adaptation, including in comparison to their non-refugee peers. The main focus of the study is subsequently on whether and how refugees’ psychological adaptation is linked to the school organizational model they initially attended.

Special conditions for the psychological adaptation of adolescent refugees

The psychological adaptation of refugee adolescents can be understood from a developmental perspective (e.g., Masten et al., 2006) as well as from an acculturative perspective (Berry et al., 2006; Ward, 1996, 2001). Immigrant adolescents have to master both developmental tasks (e.g., establishing close friendships, doing well in school, and forming a coherent sense of self; Motti-Stefanidi et al., 2012) and acculturative tasks (e.g., learning a new language, establishing social ties with residential peers, and learning how to navigate between cultures; Suárez-Orozco et al., 2018). These tasks are often intertwined (Michel et al., 2012) and can be experienced as stressful.

As young refugees often encounter particularly stressful pre-, peri-, and post-migration events and conditions (Ryan et al., 2008), they are likely to experience even more acculturative stress than voluntary immigrants (Berry et al., 1987). Before or during their flight, they often underwent or witnessed traumatic events or the loss of, or separation from, family and friends, which can promote mental health problems (Fazel et al., 2012; Heptinstall et al., 2004; Lustig et al., 2004). In particular, adolescents suffer from the loss of friends and peers who are important for emotional support during this developmental phase (Wentzel et al., 2016). Moreover, many young refugees have interrupted schooling biographies due to school closures or destruction in their home country as well as limited schooling opportunities in refugee camps (Brown et al., 2006; Dryden-Peterson, 2016; Sirin & Rogers-Sirin, 2015). In the receiving country, these interruptions and resulting learning gaps can increase refugee students’ school-related stress, adding to the challenges associated with the unfamiliarity of the educational system and teacher expectations. Other post-migration stressors include the special challenges refugee families often face, such as living in shared accommodations, insecure residence status, financial strains, and mental health issues of caregivers (Bryant et al., 2018; Fazel et al., 2012; Heptinstall et al., 2004; Porter & Haslam, 2005). Psychological adaptation can hence be especially challenging for refugee adolescents.

Despite these challenges, many refugee children and adolescents adapt well: 2 to 3 years after their immigration to Australia, refugees between 5 and 17 years expressed a psychological adaptation that was, in most domains, comparable to their Australian peers (Lau et al., 2018; Zwi et al., 2018). A large-scale study of ninth graders in Germany similarly showed that many recently arrived refugee adolescents were satisfied with their school experience, although to a slightly lower degree than their classmates with and without migration background (Henschel et al., 2019).

Different indicators are used to assess psychological adaptation. The literature often draws on general, cross-domain indicators, such as life satisfaction and self-esteem (e.g., Schotte et al., 2018), global self-worth (e.g., Kovacev & Shute, 2004), (lack of) depressive symptoms (e.g., Michel et al., 2012), or (absence of) emotional and behavioral problems (e.g., Lau et al., 2018). The absence of emotional and behavioral problems is a key indicator of psychological adaptation for all adolescents regardless of migration background (Roeser et al., 2000) and is related to better physical health and higher school achievement in refugee adolescents (Lau et al., 2018). The cognitive component of subjective well-being, life satisfaction, is a core component of a good life (Diener et al., 2002). It is also linked with (immigrant) adolescents’ satisfaction with school (Chow, 2007; Suldo et al., 2006), and it can also act as a protective factor against stressful life events (Suldo & Huebner, 2004).

Since adolescents spend most of their day at school, it is the most important developmental (Roeser et al., 2000) and acculturative (Motti-Stefanidi et al., 2012; Schachner et al., 2018; Suárez-Orozco et al., 2018) context for (immigrant) adolescents. Hence, indicators that reflect psychological adaptation to the school context, such as sense of school belonging or school satisfaction, are also often viewed as key aspects of adolescents’ psychological adaptation (e.g., Kia-Keating & Ellis, 2007; Pittman & Richmond, 2007). Sense of school belonging is related to various positive emotional and behavioral outcomes (Osterman, 2000), including lower levels of depression and higher self-efficacy in refugee adolescents (Kia-Keating & Ellis, 2007).

The role of school organizational models in the adaptation of newly arrived students

There are different approaches to school newly arrived adolescents. Although refugee adolescents’ conditions differ from those of other migrants (e.g., Edele et al., 2021), most countries do not differentiate between refugees and other newly arrived immigrant students in their approaches to include them in the educational systems (for an overview of various countries, see Crul et al. (2016) and Crul et al. (2019)). A common approach, which is, for instance, practiced in the USA (Short & Boyson, 2012) and Australia (Correa-Velez et al., 2010; Woods, 2009), is to initially school newly arrived adolescents in newcomer classes, either in separate schools or in separate classes within regular schools. It is also common practice in many European countries to initially (partially) separate newly arrived refugee students from residential students, including in Germany (Vogel & Stock, 2017), Sweden (Tajic & Bunar, 2020), and Norway (Hilt, 2017).

The main idea behind separately schooling newly arrived immigrants is to enable a quick language acquisition since they usually do not have sufficient command of the language of instruction to follow the regular curriculum. Relating to refugee students, separate schooling further offers the opportunity to address their special challenges, including limited schooling experiences and special emotional needs. Separate schooling can also ease school organization as refugees often enter the school system at irregular times during the school year and typically with limited language skills, which can disrupt the schooling of regular classes.

The role of separate schooling for refugee students’ adaptation is inconclusive and controversial. Some stakeholders argue that—depending on the specific circumstances of the respective school—the transitional separate provision can be useful. Existing research indicated that teachers perceive newcomer classes as safe spaces for newly arrived students where they meet peers with similar experiences and backgrounds, which can support their psychological adaptation and ethnic identification (Motti-Stefanidi et al., 2012). There is some empirical indication suggesting that teachers in newcomer classes have more resources at hand to focus on the needs of newly arrived refugees compared to teachers in regular classes and that teachers of these classes tend to be highly motivated (Massumi, 2019). Newly arrived students in separate classes indicated to feel more at ease when practicing their emerging language skills (Lang, 2019) and more easily developed a sense of belonging (Due et al., 2016). Separate schooling may thus reduce stress, provide specific support, and boost the psychological adaptation of newly arrived refugees.

Other stakeholders characterize separate schooling as exclusive and detrimental (Hilt, 2017; Karakayalı, zur Nieden, Groß et al., 2017; Panagiotopoulou et al., 2017) and strongly advocate the quick inclusion of refugees in regular classes. Scholars have pointed out that newcomer classes reflect a deficit perspective on newly arrived students as they focus on their limited skills in the language of instruction (Panagiotopoulou & Rosen, 2018) and deprive refugee students from opportunities to show their abilities and skills (Due & Riggs, 2009). Newcomer classes often include students of different ages and with different prior schooling experiences, and there often is a high fluctuation due to new arrivals, departures, and deportation (Karakayalı, zur Nieden, Kahveci et al., 2017). This could make it difficult to build friendships and to develop a sense of group and belonging. There is further evidence suggesting that newly arrived students in separate provision experience increased feelings of exclusion (Miller et al., 2005) and that separate provision can increase the barrier to use the new language outside of the safe space of a newcomer class (Lang, 2019). Separate schooling in newcomer classes could thus also increase the refugee adolescents’ stress and jeopardize their psychological adaptation.

A different strategy to school newly arrived students is to include them directly in regular classes. This approach involves the advantage of facilitating their contact with residential peers, which offers informal language learning opportunities and enables refugee adolescents to get into contact with the culture of the receiving country (Nilsson & Axelsson, 2013). This could benefit their acculturation process (Motti-Stefanidi et al., 2012) and ultimately help them to settle and adapt psychologically. However, research on students who migrated in adolescence suggested that learning in a regular class can also be challenging to their school adaptation since their experiences and former education is often disregarded in lessons and they often cannot use their resources (Massumi, 2019). They also often face difficulties to follow the subject matters due to language difficulties (Nilsson & Axelsson, 2013). There is indication that refugee students experience more frustration, boredom, and a greater fear of speaking in lessons in regular classes than in lessons in newcomer classes (Schmiedebach & Wegner, 2019). This situation can contribute to feelings of exclusion within regular classes (Massumi, 2019). Moreover, teachers in regular classes do not only have limited resources; they also often lack the skills to deal with the special situation of refugee students. This can result in an overburdening of students as well as teachers (Tajic & Bunar, 2020), thus increasing students’ stress and compromising their psychological adaptation.

In a third approach, mixed school organizational models, students receive some lessons in a newcomer class that focusses on language development, but they also attend a regular class in which they typically study the less language-based subjects like sports, music, and art. Few studies to date have investigated the mixed model. Yet, it could combine the advantages of the exclusive approaches outlined above: On the one hand, the time in the newcomer class can offer a safe space for emotional problems and promote focused language development. On the other hand, the inclusion in regular classes offers contact with residential peers who can help to navigate the educational system of the receiving country. Moreover, joint schooling with local students could help to develop a sense of belonging to the receiving context, and dual identification with the ethic context and the receiving context is linked to good psychological adjustment (Schotte et al., 2018).

Empirical studies that directly compare how different schooling approaches relate to refugee students’ school adaptation, including their psychological adaptation, are scarce. Whereas most of the studies outlined in this section were regional qualitative studies, few larger quantitative studies on the matter exist. One quantitative study that did compare separate and conjoint schooling models, conducted in Turkey, showed a better psychological adaptation of refugee students in regular classes (Karadag & Gokcen, 2020). However, the study examined a relatively small sample and failed to control for confounding factors on the individual level, such as age, sex, and years spend in the receiving country, and on the level of the family or the school. Thus, it remains an open empirical question whether, and in what fashion, the learning in different school organizational models is related to the psychological adaptation of refugee adolescents.

Present study

Drawing on a large and representative dataset, the present study examined the psychological adaptation of recently arrived refugee adolescents in Germany. In a first step, we examined the psychological adaptation of refugee adolescents compared to residential peers with and without migration background. The main purpose of the study was to determine whether the psychological adaptation of recently arrived refugee adolescents was linked to the school organizational model they had initially attended (mixed approach, regular class, or newcomer class).

Theoretical arguments and previous findings relating to the effects of attending a newcomer class or a regular class on refugee students’ psychological adaptation are not conclusive. Both models offer advantages, but also potential pitfalls (see “The role of school organizational models in the adaptation of newly arrived students” section). Mixed approaches, in which refugee students attend regular classes with residential peers, but also receive separate education in newcomer classes, could thus combine the benefits of both models and prevent their respective disadvantages. They facilitate contact with residential peers and simultaneously allow to tackle the special emotional and educational needs of refugee students. We therefore assumed that mixed approaches provide the best conditions for the psychological adaptation of refugee adolescents.

The German context is very well suited to investigate this issue. Newly arrived refugees are allocated to the different federal states according to the Königssteiner Schlüssel (Königsstein Key; see Bartl (2019)) that realizes a distribution according to tax revenue and the size of the population of the respective state, but largely independent of refugees’ characteristics. Due to different regulations in the federal states regarding the establishment of newcomer classes (for an overview, see Massumi et al. (2015) and Vogel and Stock (2017)), to regional differences in the conditions (e.g., number of refugees schools accommodated), and to decisions at individual schools, all three types of school organizational models were simultaneously practiced in Germany within the last years. Whereas newcomer classes, in which newly arrived students supposedly learn for a transitional time period for a maximum of 12 to 24 months, expanded in the years after the high influx of refugee students (Autorengruppe Bildungsberichterstattung, 2016), considerable shares of newly arrived students directly learned in regular classes or were schooled in a mixed model (Hofherr, 2020).

To capture a broad understanding of psychological adaptation, our study considered one school-related and two more general, cross-domain indicators of psychological adaptation: (i) sense of school belonging, (ii) emotional and behavioral problems, and (iii) life satisfaction. Although the allocation of refugee adolescents to the school organizational models was largely independent of their characteristics (see previous section), we still controlled for factors on the individual and family level, and also on the school and community level, to ensure that our findings are not a spurious result of random differences. Research indicates that at the individual level, personality (Echterhoff et al., 2020; Suldo et al., 2015; Ward, 2001), gender (Montgomery & Foldspang, 2007), age (Michel et al., 2012), time in country of residence (Michel et al., 2012), and the legal status (Homuth et al., 2020; Steel et al., 2011) are linked to psychological adaptation. Country of origin could also be relevant in this context due to the respective events refugees had experienced there prior to their migration and due to differential prospects of staying in Germany. At the family level, the family composition (Amato & Keith, 1991; Kalmijn, 2017), the living situation (Evans, 2006), and the mental health of the parents (Bryant et al., 2018; Shehadeh et al., 2015) have shown to be important in this context. In Germany, students are divided according to their academic achievements into different school tracks after primary school (usually in grade 5) with the Gymnasium being the most demanding one that leads to a university entrance certificate. Research indicates that the different school tracks differ in their student composition and offer different social and learning environments (Baumert et al., 2006), which could affect students’ psychological adjustment. At the community level, community size could affect the psychological adaptation of adolescent refugees, as cities are often ethnically more diverse and offer different acculturative conditions than rural areas (Schech, 2014; Weidinger et al., 2017).

Methods

Sample

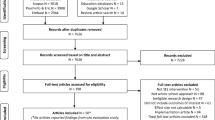

To analyze our research questions, we used the data of the IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees, a representative panel study jointly conducted by the Institute for Employment Research (IAB); the Research Centre on Migration, Integration, and Asylum of the Federal Office of Migration and Refugees (BAMF-FZ); and the Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) at the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin). Data collection started in 2016, is since yearly repeated, and includes refugees residing across all federal states of Germany. Sampling was based on the German Central Register of Foreigners (Ausländerzentralregister) and targets people who came to Germany between 2013 and 2016 and who applied for asylum (for more details of the target population and the sampling procedure, see Jacobsen et al. (2019) and Kroh et al. (2017)). The study is conducted as a household survey, and every adult household member is asked to participate in a personal interview. Specific cohorts of adolescent household members are also interviewed. The survey is part of the German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP; Goebel et al., 2019). Our analyses drew on data from the 2017 and 2018 survey waves. We analyzed the responses of refugee adolescents who were or turned 12, 14, or 17 in the respective survey year (labeled as “12-,” “14-,” and “17-year-olds,” hereafter) and also used information from their primary caregivers. Excluding cases who indicated a time of arrival in Germany before 2013 (n = 6) and cases with sample weights that were zero (n = 4) resulted in a sample size of N = 700 (n = 280 12-year-olds, n = 219 14-year-olds, n = 201 17-year-olds; Mage = 15.1, SEage = 2.2). More than half of the refugee adolescents came from Syria (52.7%), substantial other heritage countries were Afghanistan (13.8%) and Iraq (13.6%), and 60.0% of them were male. The refugee adolescents had been in Germany for 0 to 5 years at the time of the interview; most had been in Germany for 2 or 3 years (M = 2.4, SD = 0.97). They lived in communities of different sizes: whereas 31.0% lived in rural areas, 33.9% lived in large cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants.

Measures

Psychological adaptation

To evaluate the psychological adaptation of refugee adolescents, we analyzed the following dependent variables: sense of school belonging, emotional and behavioral problems, and life satisfaction. The survey assessed the sense of school belonging with nine items included in the PISA study (OECD, 2013). Students were asked to indicate on a 4-point scale to what degree they agreed with statements like “I feel like I belong at school,” “Other students seem to like me,” and “I feel like an outsider (or left out of things) at school” (inversely coded). The internal consistency of the scale was α = 0.86. To capture the emotional and behavioral problems of the refugee adolescents, we used the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 1997). The SDQ is a widely used indicator of psychological adaptation (Achenbach et al., 2008) that has also been successfully employed in refugee samples (Lau et al., 2018; Panter-Brick et al., 2014). We used the 20 items of the scales “hyperactivity,” “emotional problems,” “conduct problems,” and “peer problems” to build a total problem score that had a reliability of α = 0.74. Sample items of the respective scales are “I am restless, I cannot stay still for long” (hyperactivity), “I worry a lot” (emotional problems), “I get very angry and often lose my temper” (conduct problems), and “I would rather be alone than with people of my age” (peer problems). General life satisfaction was assessed with one item on a 11-point Likert scale ranging from 0 “Not at all satisfied” to 10 “Completely satisfied.” While single-item measures are not fully satisfactory and domain-specific life satisfaction could be informative, studies have shown that the single-item measure is valid for adolescents (Jovanović, 2016; Jovanović & Lazić, 2020).

School organizational model

Adolescents who indicated they attended a school in Germany were asked how they were schooled when they started school in Germany. Possible options were “directly in a regular class,” “as well in a regular class as in a special class for refugees,” and “only in a special class for refugees.” Their responses were coded as “regular class,” “mixed approach,” and “newcomer class.”

Control variables

At the individual level, the study considered students’ age group (12-, 14-, or 17-year-olds), gender, years in Germany, country of origin (Syria vs. other), and personality (big five: openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, neuroticism; as assessed in the SOEP, see Richter et al. (2017)) as control variables. At the household level, we considered insecure residence title of one primary caregiver, living in a shared accommodation, single parent household, mental health component score (MCS; Andersen et al., 2007) of one primary caregiver, high educational background if one or more members of the household had at least completed upper secondary education, and the community size (labeled “rural” if less than 20,000 residents, “medium city” if 20,000 to less than 100,000 residents, and “large city” if more than 100,000 residents) of the family’s community of residence. The attended school track is considered a control variable at the school level. Gymnasium was coded as “academic” in comparison to all other tracks that were labeled as “non-academic.”

Analyses

We analyzed the outcome variables descriptively and compared the adolescent refugees’ psychological adaptation to that of their residential peers. We used data from the PISA-2018-study (data release October 2020) as a benchmark for refugee adolescents’ sense of school belonging. Since sense of school belonging was assessed with only six items in the PISA-2018-study (OECD, 2020), we restricted our data to these six items for the comparison. The PISA study captures a representative sample of 15-year-old students in Germany who have studied the language of instruction for at least 1 year (Mang et al., 2019). To compare the refugee adolescents’ emotional and behavioral problems and their life satisfaction to their peers, we used data from adolescents who participated in the regular SOEP study in 2017 and 2018. The SOEP provides representative data for private households in Germany (Goebel et al., 2019) and allows for differentiating between residential peers with migration background but without flight experience and peers without migration background. We used a raking procedure (Lohr, 2009, p.344) to adjust the sample weights so that the age distribution of the SOEP comparison groups matched that of the refugee group. The emotional and behavioral problems could only be compared for 12- and 14-year-olds due to data restrictions in the SOEP comparison sample.

Missing values on the analyzed variables ranged from 0% on years in Germany to 16.6% on emotional and behavioral problems. We dealt with the missing values using multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE; White et al., 2011). For this, in addition to the variables used in the later analyses, we included auxiliary variables at the level of the adolescent and at the level of the primary caregiver in the imputation model. We imputed 20 complete datasets. The analyses were then restricted to cases that showed no missing values on the respective dependent (i.e., sense of school belonging, emotional and behavioral problems, life satisfaction) and independent (i.e., school organizational model) variable, which has shown to be a valuable approach (Kontopantelis et al., 2017).

To evaluate whether the school organizational model at the beginning of the schooling in Germany is linked to the subsequent psychological adaptation of the refugee adolescents, we employed linear regression analyses for each outcome variable. We report two models: (a) linear regression analyses in which the psychological outcome variable was regressed on the school organizational model (reference category: mixed approach). In a second set of analyses, (b) we additionally included the control variables on individual, family, school, and community levels as described above. In all regression models, standard errors were clustered at the household level to account for dependencies in sibling observations. All our analyses included sample weights and were estimated using Stata version 16.1 (StataCorp, 2019).

Results

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive analyses. The largest share of newly arrived refugee students directly started learning in a regular class (43.7%). Roughly one in three refugee students (36.1%) was taught exclusively in a newcomer class, whereas about one in five (20.2%) indicated that they had attended a mixed approach in the beginning. Refugee adolescents showed high levels of a sense of belonging to school, few emotional and behavioral problems, and a good life satisfaction with average mean scores well above (in case of emotional and behavioral problems: below) the theoretical mean of the scales (see Table 1).

The comparison of refugee students’ sense of school belonging, emotional and behavioral problems, and life satisfaction to their peers with migration background without flight experience and to peers without migration background (see Table 2) indicated that—with one exception—refugee adolescents showed comparable or even higher levels of psychological adaptation. Independent t-tests were used to test group differences, based on a significance level of p < 0.05. For sense of school belonging, refugee adolescents expressed significantly higher mean values than 15-year-old residential adolescents with (t(1963) = 14.35, p < 0.001) and without (t(3214) = 14.23, p < 0.001) migration background who participated in the PISA-2018-study. With regard to emotional and behavioral problems, 12- and 14-year-old refugees showed significantly lower mean problem scores than both comparison groups: residential peers with migration background but without flight experience (t(902) = − 2.51, p = 0.012) and peers without migration background (t(1928) = − 7.43, p < 0.001). The only exception is that recently arrived refugees indicated a significantly lower life satisfaction than their peers from migrated families without flight experience (t(1322) = − 2.22, p = 0.026). However, their life satisfaction did not differ significantly from that of their peers without migration background (t(2791) = 0.41, p = 0.685).

The linear regression analyses revealed differences in refugee adolescents’ sense of school belonging in the expected direction: Refugee students in regular classes and in newcomer classes showed a significantly lower sense of school belonging than refugee students who learned in a mixed approach (Table 3, model 1a). This was also the case when control variables were taken into account (Table 3, model 1b). Contrary to our assumptions, we found no advantage of mixed approaches for emotional and behavioral problems or life satisfaction (Table 3, models 2 and 3, respectively). Conversely, refugee adolescents who initially attended newcomer classes showed significantly lower total problems scores than refugees who first learned in mixed approaches. This effect, however, was partly explained by the control variables and was no longer statistically significant when the control variables were taken into account (model 2b). The multiple regression analyses (models 1b, 2b, and 3b) further indicated significant age effects in all models, and effects of personality and primary caregivers’ mental health emerged in at least two of the three models. The analyses showed that the school organizational model alone explained only a little part of the variance in the psychological adaptation of adolescent refugees (a maximum of 2% for sense of school belonging). The full models explain between 18% (sense of school belonging) and 36% (emotional and behavioral problems) of the variance.

Discussion

Given the high number of refugee students around the world (UNHCR, 2020) and the variety of approaches to school them, understanding whether, and if so how, school organizational models differently foster refugees’ school adaptation is critical. Despite its theoretical and practical significance, empirical evidence on the issue was hitherto scarce. Drawing on a representative sample of recently arrived refugees in Germany, this study determined how well refugee adolescents are psychologically adapted and examined how psychological adaptation is related to the school organizational model (newcomer classes, direct immersion in regular classes, or mixed approach) that refugee students initially attended.

Refugee students’ psychological adaptation

Our results indicate that refugee adolescents on average are psychologically well adapted. This is largely in line with previous findings that have shown a good psychological adaptation and remarkable resilience of refugee children and adolescents (Henschel et al., 2019; Correa-Velez et al., 2015; Lau et al., 2018; Zwi et al., 2018). Our results complement previous findings in that adolescents with a refugee background showed similar levels of psychological adaptation as their peers with and without migration background. For emotional and behavioral problems and for sense of school belonging, we found an even higher adaptation for refugee adolescents compared to their non-refugee peers. Such an advantage of refugees was not observed in a recent study in Germany (Henschel et al., 2019). The observed difference may be due to differences in the survey setting: The testing situation in the previous study, a national assessment study of school achievement, was likely very demanding and possibly frustrating for recently arrived refugee students due to their on average lower language skills and competencies in the tested domains (Schipolowski et al., 2021). This situation may have led to a more negative self-assessment and ultimately sense of school belonging, as the belief about oneself can influence the reported emotions (Robinson & Clore, 2002). Despite these slight differences, the current state of research concordantly indicates that refugee adolescents in Germany are, in spite of their special challenges (Edele et al., 2021), surprisingly well adapted in terms of their psychological adaptation.

School organizational model and refugee students’ psychological adaptation

In contrast to the pre-migration experiences of refugees, their post-migration situation can be modified by the receiving country, which is why scientists and practitioners have called to put more emphasis on post-migration factors in refugees’ adaptation (e.g., Matthews, 2008). For refugee adolescents, their school experience is one of the most important factors in their acculturation (e.g., Suárez-Orozco et al., 2018). We hypothesized that a mixed schooling approach that combines specialized education in a newcomer class with inclusion in a regular class is related to better psychological adaptation in refugee adolescents than immediate immersion in a regular class or exclusively attending a newcomer class. Our analyses did not unequivocally support this assumption. In line with it, refugee adolescents who first learned in mixed approaches reported a higher sense of school belonging. Emotional and behavioral problems and life satisfaction, in contrast, were not systematically related to the attended school organizational model. Of the three indicators analyzed, sense of school belonging is conceptually most immediately linked to students’ school experience. It is plausible that the school organizational model affects this school-related aspect of psychological adaptation of refugee adolescents the most. Our results thus hint at a certain advantage of mixed schooling approaches.

However, the overall pattern of results and the fact that the attended school organizational model explained only a small share of the variation in refugee adolescents’ psychological adaptation supports the proposition that no type of school organizational model provides a major advantage for refugee students’ adaptation (Massumi, 2019), at least not in the medium term. This result contrasts findings from qualitative studies, which have emphasized negative effects of newcomer classes, such as a reduced contact with residential peers, feelings of exclusion, and the fostering of a deficit perspective (e.g., Karakayalı, zur Nieden, Kahveci et al., 2017; Panagiotopoulou & Rosen, 2018). Whether our finding generalizes to different outcomes, particularly language learning and educational achievement, is an open question to date. Other school-related factors largely unrelated to the structural approach to school refugee students, such as the personnel and material resources of the schools, quality of the curriculum, school climate, and supportive relationships with teachers and peers, could be more important for refugee students’ psychological adaptation (Allen & Kern, 2017; Berthold, 2000; Fazel et al., 2012; Kovacev & Shute, 2004; Suárez-Orozco et al., 2018). Moreover, their psychological adjustment is linked to individual and family characteristics. Our study indicated age effects which are in line with the literature that shows a decline of psychological adaptation in the course of adolescence (e.g., Gillen-O’Neel & Fuligni, 2013; Goldbeck et al., 2007; Michel et al., 2012). In accordance with the literature, personality (e.g., we observed a negative relation between neuroticism and psychological adaptation; Salami, 2011; Suldo et al., 2015) and the primary caregiver’s mental health were also associated with the adolescent’s psychological adaptation (Bryant et al., 2018; Shehadeh et al., 2015).

The different school organizational models have been discussed vividly in light of their inclusive potential for newcomer refugees. Full inclusion values all aspects of diversity and responds to the needs of all learners (Ainscow & Messiou, 2018). Applied to the education of refugees, it refers to including them in the educational system while taking into account their special educational and emotional needs (e.g., Block et al., 2014; Pugh et al., 2012; Tajic & Bunar, 2020; Taylor & Sidhu, 2012). It is an openly debated issue which of the models to school newly arrived students comes closest to the ideal of inclusion. Interestingly, for all the presented models, there are proponents claiming (and opponents rejecting) that they suit the principles of inclusion best. For instance, although the idea of inclusion rejects segregation on whatever ground and newcomer classes are hence often characterized as exclusive (Panagiotopoulou et al., 2017), some teachers believe that newcomer classes offer a “safe start,” thereby paving the way for inclusion (Tajic & Bunar, 2020). Similarly, while some scholars have viewed direct immersion in regular classes as, at least to some degree, inclusive (Karakayalı, zur Nieden, Groß et al., 2017), others emphasized that without further school reforms, and this approach represents a misinterpretation of the concept of inclusion, since it does not sufficiently consider the special educational and emotional needs of refugee students (Tajic & Bunar, 2020). Taken together, none of the existing models can be characterized as being fully inclusive, and scholars have argued that school reforms that overcome the current deficit perspective are needed to facilitate actual inclusion (Pugh et al., 2012). It is plausible to assume that more inclusive approaches would promote refugee students’ psychological adjustment better than the currently practiced models we examined.

Our findings indicate that in either school organizational model, the majority of refugee students are psychologically quite well-adapted. This raises the question why recently arrived refugee students, who face many special challenges and were schooled in models that are not fully inclusive, express such high levels of psychological adaptation. It may be part of the explanation that school attendance positively benefits psychological adaptation because it structures daily life (Matthews, 2008) and facilitates contact with peers. It should thus be a high priority to enable newly arrived refugee children and adolescents to attend school as soon as possible. Factors outside the school setting may also play a crucial role: Following the often stressful and adverse experiences before and during their flight, refugee adolescents may particularly value the return to an ordinary life in the (relative) safety of a country under the rule of law that is not in war or other armed conflicts.

In light of the, on average, high levels of psychological adaptation of refugee students, it should not be forgotten that refugee adolescents, who are often treated as a homogenous group, differ largely with regard to their experiences before and during the flight, their former schooling experiences, their housing and family situation, their personality, their prospects to remain permanently in Germany, and their mental and physical health. In our analyses, there are also refugee students who reported having a very low psychological adaptation. The individual should not be lost sight of and all school organizational measures should be tailored as much as possible to the specific needs and circumstances of the individual learners. Teachers in all schooling approaches also need to be alert to signs of mental health problems in refugee students and, if necessary, help them seek psychosocial support.

Limitations and future research

Our study is limited in several ways. First, our sample was restricted to three age cohorts. Yet, the schooling approaches might involve different implications at different educational stages. For instance, (perceived) knowledge gaps between non-refugee peers and refugee adolescents, time until end of compulsory schooling, and importance of peers, play a more or less important role. Potential effects might thus have been obscured due to the restriction to these age groups. A second limitation of our study is that it did not assess how the respective school organizational models were implemented. The used indicator is thus a rather broad measure of the schooling approach with no possibilities to find out whether specific aspects of the implemented model are helpful for refugees’ psychological adaptation. Thirdly, the data do not include unaccompanied refugee minors who may be particularly challenged in their adaptation processes. Hence, our results cannot be readily applied to this particularly vulnerable group (e.g., Derluyn & Broekaert, 2007; Vervliet et al., 2014). We further do not know whether the findings that many of the refugee adolescents who have recently arrived in Germany are well adapted psychologically are only a snapshot due the cross-sectional nature of our study that assessed refugee’s adaption comparably early after their migration, and whether our findings also apply to other school-related outcomes. Moreover, the findings are only partially transferrable to countries other than Germany since the school organizational models as well as the acculturation conditions generally differ across contexts. Nevertheless, comparable approaches to school newly arrived students exist in some European countries such as Norway (Hilt, 2017) and Sweden (Nilsson & Axelsson, 2013), and our findings are to some extent informative for these settings as well.

Future research should include further age groups and also focus on the psychological adaptation of unaccompanied minor refugees, since it is well possible that different mechanisms are at play. Scholars are also well advised to employ more specific measures of the implementation of the schooling approach and to put more emphasis on the specific implementation of the school organizational model than on the schooling approach itself. Another important venue for future research is to examine cross-national similarities and differences in the ways to include newly arrived refugees in school. To find out whether refugees also show a good socio-cultural adaptation in the medium and long term and on other indicators of school adaptation, longitudinal analyses focusing on a larger variety of outcomes, including educational success and social inclusion, are necessary.

Outlook and implications

Most European educational systems will continue to school refugee students in the coming years because many of those who have already arrived are likely to stay and, most likely, new refugee children and adolescents will arrive. Thus, it is important to question and evaluate existing schooling practices in order to enable as many students as possible to develop their potential, adapt well, and participate in society. Overall, our results show a slight advantage for the mixed model but indicate that strong reservations about a particular school organizational model are not justified. Researchers and practitioners should focus more on the specific processes that are helpful for refugee students’ psychological adaption and on factors beyond the school organizational models that have shown to be helpful for psychological adaptation in other studies, for instance, teacher-student relationships (e.g., Chiu et al., 2016; OECD, 2017, Osterman, 2010), social integration with peers (e.g., Fazel, 2015, Kiefer et al., 2015), development of a dual identity (e.g., Kovacev & Shute, 2004), or dealing with traumatic experiences in the school context (Fazel et al., 2009, Fazel & Betancourt, 2018). Moreover, scholars and practitioners should strive to implement and investigate more inclusive approaches to school newly arrived adolescents, for example, by following a holistic and whole-school approach that does not only focus on language acquisition, but on the variety of needs the newly arrived students have (Block et al., 2012; Pugh et al., 2012; Taylor & Sidhu, 2012). Promising approaches in this context are the establishment of supportive networks (Block et al., 2014) and the implementation of structural changes throughout the school (Pugh et al., 2012). This could support young refugees to apply their resources and demonstrate their skills in school, including their heritage language skills, practical skills, and cultural knowledge.

Lisa Pagel. Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP), DIW Berlin, Mohrenstr. 58, 10117 Berlin, Germany. Email: lpagel@diw.de.

Current themes of research:

School adaptation of refugee children and adolescents. Psychological well-being of refugee children and adolescents.

Most relevant publications in the field of Psychology Education:

No previous publications

Aileen Edele. Berlin Institute for Integration and Migration Research (BIM) & Department of Education Studies, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Unter den Linden 6, 10099 Berlin, Germany.

Current themes of research:

School adaptation of children and adolescents from immigrant families. Learning and instruction in ethnically diverse settings. Adaptation of refugee children and adolescents. The role of multilingualism in educational success. Cultural identity.

Most relevant publications in the field of Psychology Education:

Edele, A., Kristen, C., Stanat, P. & Will, G. (2021): The education of recently arrived refugees in Germany: Conditions, processes, and outcomes [Special Section]. Journal of Educational Research Online, 13(1), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.31244/jero.2021.01.

Schipolowski, S., Edele, A., Mahler, N. & Stanat, P. (2021): Mathematics and science proficiency of young refugees in secondary schools in Germany. Journal of Educational Research Online, 13(1), 78–104. https://doi.org/10.31244/jero.2021.01.03.

Edele, A., Jansen, M., Schachner, M. K., Schotte, K., Rjosk, C. & Radmann, S. (2020). School track and ethnic classroom composition relate to the mainstream identity of adolescents with immigrant background in Germany, but not their ethnic identity. International Journal of Psychology, 55(5), 754–768. 10.1002/ijop.12677.

Edele, A., Kempert, S. & Schotte, K. (2018). Does competent bilingualism entail advantages for the third language learning of immigrant students? Learning and Instruction, 58, 232–244. 1016/j.learninstruc.2018.07.002.

Schotte, K., Stanat, P. & Edele, A. (2018). Is integration always most adaptive? The role of cultural identity in academic achievement and in psychological adaptation of immigrant students in Germany. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(1), 16–37. 10.1007/s10964-017-0737-x

Data availability

The paper uses data from the German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP), including the IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees. Access to the data for scientific purposes is possible via a data distribution contract (for more information, please refer to https://www.diw.de/en/diw_01.c.601584.en/data_access.html).

Code availability

All analyses were estimated using Stata version 16.1 (StataCorp, 2019). The ado-files renames, mdesc, ipfweight, and mibeta were used.

References

Achenbach, T. M., Becker, A., Döpfner, M., Heiervang, E., Roessner, V., Steinhausen, H.-C., & Rothenberger, A. (2008). Multicultural assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology with ASEBA and SDQ instruments: Research findings, applications, and future directions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(3), 251–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01867.x

Ainscow, M., & Messiou, K. (2018). Engaging with the views of students to promote inclusion in education. Journal of Educational Change, 19(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-017-9312-1

Allen, K.-A., & Kern, M. L. (2017). School belonging in adolescents: Theory, research and practice. Springer.

Amato, P. R., & Keith, B. (1991). Parental divorce and the well-being of children: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 110(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.26

Andersen, H. H., Mühlbacher, A., Nübling, M., Schupp, J., & Wagner, G. G. (2007). Computation of standard values for physical and mental health scale scores using the SOEP version of SF-12v2. Schmollers Jahrbuch, 127(1), 171–182.

Autorengruppe Bildungsberichterstattung (Ed.). (2016). Bildung in Deutschland 2016: Ein indikatorengestützter Bericht mit einer Analyse zu Bildung und Migration [Education in Germany 2016: An indicator-based report with an analysis of education and migration]. Bertelsmann. http://www.bildungsbericht.de/de/bildungsberichte-seit-2006/bildungsbericht-2016/pdf-bildungsbericht-2016/bildungsbericht-2016.

BAMF. (2014). Das Bundesamt in Zahlen 2013. Asyl, Migration und Integration [The Federal Office in figures 2013. Asylum, migration and integration]. https://www.bamf.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/DE/Statistik/BundesamtinZahlen/bundesamt-in-zahlen-2013.pdf

BAMF. (2015). Das Bundesamt in Zahlen 2014. Asyl, Migration und Integration [The Federal Office in figures 2014. asylum, migration and integration]. https://www.bamf.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/DE/Statistik/BundesamtinZahlen/bundesamt-in-zahlen-2014.pdf

BAMF. (2016). Das Bundesamt in Zahlen 2015. Asyl, Migration und Integration [The Federal Office in figures 2015. Asylum, migration and integration]. http://www.bamf.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/DE/Publikationen/Broschueren/bundesamt-in-zahlen-2015.pdf

BAMF. (2017). Das Bundesamt in Zahlen 2016. Asyl, Migration und Integration [The Federal Office in figures 2016. Asylum, migration and integration]. https://www.bamf.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/DE/Statistik/BundesamtinZahlen/bundesamt-in-zahlen-2016.pdf

Bartl, W. (2019). Institutionalization of a formalized intergovernmental transfer scheme for asylum seekers in Germany: The Königstein Key as an indicator of federal justice. Journal of Refugee Studies. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fez081

Baumert, J., Stanat, P., & Watermann, R. (2006). Schulstruktur und die Entstehung differenzieller Lern- und Entwicklungsmilieus [School structure and the emergence of differentiated learning and development environments]. In J. Baumert, P. Stanat, & R. Watermann (Eds.), Herkunftsbedingte Disparitäten im Bildungswesen: Differenzielle Bildungsprozesse und Probleme der Verteilungsgerechtigkeit (pp. 95–188). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-90082-7_4

Berry, J. W., Kim, U., Minde, T., & Mok, D. (1987). Comparative studies of acculturative stress. International Migration Review, 21(3), 491–511. https://doi.org/10.1177/019791838702100303

Berry, J. W., Phinney, J. S., Sam, D. L., & Vedder, P. (2006). Immigrant youth: Acculturation, identity, and adaptation. Applied Psychology, 55(3), 303–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2006.00256.x

Berthold, S. M. (2000). War traumas and community violence. Journal of Multicultural Social Work, 8(1–2), 15–46. https://doi.org/10.1300/j285v08n01_02

Block, K., Cross, S., Riggs, E., & Gibbs, L. (2014). Supporting schools to create an inclusive environment for refugee students. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 18(12), 1337–1355. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2014.899636

Brown, J. A., Miller, J., & Mitchell, J. (2006). Interrupted schooling and the acquisition of literacy Experiences of Sudanese refugees in Victorian secondary schools. The Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 29(2), 150. https://doi.org/10.3316/ielapa.157075354919791

Bryant, R. A., Edwards, B., Creamer, M., O’Donnell, M., Forbes, D., Felmingham, K. L., Silove, D., Steel, Z., Nickerson, A., McFarlane, A. C., Van Hooff, M., & Hadzi-Pavlovic, D. U. (2018). The effect of post-traumatic stress disorder on refugees’ parenting and their children’s mental health A cohort study. The Lancet Public Health, 3(5), e249–e258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30051-3

Buchanan, Z. E., Abu-Rayya, H. M., Kashima, E., Paxton, S. J., & Sam, D. L. (2018). 2018/03/01/). Perceived discrimination, language proficiencies, and adaptation: Comparisons between refugee and non-refugee immigrant youth in Australia. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 63, 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2017.10.006

Chow, H. P. H. (2007). Sense of belonging and life satisfaction among Hong Kong adolescent immigrants in Canada. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 33(3), 511–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830701234830

Correa-Velez, I., Gifford, S. M., & Barnett, A. G. (2010). Longing to belong: Social inclusion and wellbeing among youth with refugee backgrounds in the first three years in Melbourne Australia. Social Science & Medicine, 71(8), 1399–1408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.018

Correa-Velez, I., Gifford, S. M., & McMichael, C. (2015). The persistence of predictors of wellbeing among refugee youth eight years after resettlement in Melbourne, Australia. Social Science & Medicine, 142, 163–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.08.017

Crul, M., Keskiner, E., Schneider, J., Lelie, F., & Ghaeminia, S. (2016). No lost generation? Education for refugee children. A comparison between Sweden, Germany, The Netherlands and Turkey. In R. Bauböck & M. Tripkovic (Eds.), The integration of migrants and refugees (pp. 62–79). European University Institute. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/d68aa615-5bdd-11e7-954d-01aa75ed71a1

Crul, M., Lelie, F., Biner, Ö., Bunar, N., Keskiner, E., Kokkali, I., Schneider, J., & Shuayb, M. (2019). How the different policies and school systems affect the inclusion of Syrian refugee children in Sweden, Germany Greece Lebanon and Turkey. Comparative Migration Studies, 7(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-018-0110-6

Derluyn, I., & Broekaert, E. (2007). Different perspectives on emotional and behavioural problems in unaccompanied refugee children and adolescents. Ethnicity and Health, 12(2), 141–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557850601002296

Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., & Oishi, S. (2002). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and life satisfaction. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (2 ed., Vol. 2, pp. 63–73). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195187243.013.0017

Dryden-Peterson, S. (2016). Refugee education in countries of first asylum: Breaking open the black box of pre-resettlement experiences. Theory and Research in Education, 14(2), 131–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878515622703

Due, C., & Riggs, D. W. (2009). Moving beyond English as a requirement to fit in Considering refugee and migrant education in South Australia. Refuge Canada’s Journal on Refugees, 26(2), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.25071/1920-7336.32078

Due, C., Riggs, D. W., & Augoustinos, M. (2016). Jul). Experiences of school belonging for young children with refugee backgrounds. Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 33, 33–53. https://doi.org/10.1017/edp.2016.9

Echterhoff, G., Hellmann, J. H., Back, M. D., Kärtner, J., Morina, N., & Hertel, G. (2020). Psychological antecedents of refugee integration (PARI). Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(4), 856–879. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691619898838

Edele, A., Kristen, C., Stanat, P. & Will, G. (Hrsg.) (2021). The education of recently arrived refugees in Germany: conditions, processes, and outcomes [Special Section]. Journal of Educational Research Online, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.25656/01:22064

Evans, G. W. (2006). Child development and the physical environment. Annual Review of Psychology, 57, 423–451. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190057

Fazel, M., Reed, R. V., Panter-Brick, C., & Stein, A. (2012). Mental health of displaced and refugee children resettled in high-income countries: Risk and protective factors. Lancet, 379(9812), 266–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60051-2

Fazel, M., & Stein, A. (2002). The mental health of refugee children. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 87(5), 366–370. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.87.5.366

Gillen-O’Neel, C., & Fuligni, A. (2013). A longitudinal study of school belonging and academic motivation across high school. Child Development, 84(2), 678–692. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01862.x

Goebel, J., Grabka, M. M., Liebig, S., Kroh, M., Richter, D., Schröder, C., & Schupp, J. (2019). The German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP). Jahrbücher Für Nationalökonomie Und Statistik, 239(2), 345–360. https://doi.org/10.1515/jbnst-2018-0022

Goldbeck, L., Schmitz, T. G., Besier, T., Herschbach, P., & Henrich, G. (2007). Life satisfaction decreases during adolescence. Quality of Life Research, 16(6), 969–979. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-007-9205-5

Goodman, R. (1997). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38(5), 581–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x

Henschel, S., Heppt, B., Weirich, S., Edele, A., Schipolowski, S., & Stanat, P. (2019). Zuwanderungsbezogene Disparitäten [Immigration-related disparities]. In P. Stanat, S. Schipolowski, N. Mahler, S. Weirich, & S. Henschel (Eds.), IQB-Bildungstrend 2018. Mathematische und naturwissenschaftliche Kompetenzen am Ende der Sekundarstufe I im zweiten Ländervergleich (pp. 295). Waxmann.

Heptinstall, E., Sethna, V., & Taylor, E. (2004). PTSD and depression in refugee children–Associations with pre-migration trauma and post-migration stress. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 13(6), 373–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-004-0422-y

Hilt, L. T. (2017). Education without a shared language: Dynamics of inclusion and exclusion in Norwegian introductory classes for newly arrived minority language students. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21(6), 585–601. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2016.1223179

Hofherr, S. (2020). Allgemeinbildende Schulen. Neuzugewanderte Kinder und Jugendliche an Schulen [General education schools. Newly immigrated children and adolescents at schools]. In S. Lochner & A. Jähnert (Eds.), DJI-Kinder- und Jugendmigrationsreport 2020. Datenanalyse zur Situation junger Menschen in Deutschland (pp. 119–124). wbv media. https://www.mercator-institut-sprachfoerderung.de/fileadmin/Redaktion/PDF/Publikationen/MI_ZfL_Studie_Zugewanderte_im_deutschen_Schulsystem_final_screen.pdf

Homuth, C., Welker, J., Will, G., & Von Maurice, J. (2020). The impact of legal status on different schooling aspects of adolescents in Germany. Refuge: Canada’s Journal on Refugees, 36(2), 45–57.

Hunkler, C., & Khourshed, M. (2020). The role of trauma for integration The case of Syrian refugees. SozW Soziale Welt, 71(1–2), 90–122. https://doi.org/10.5771/0038-6073-2020-1-2-90

Jacobsen, J., Kroh, M., Kühne, S., Scheible, J. A., Siegers, R., & Siegert, M. (2019). Supplementary of the IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees in Germany (M5) 2017. SOEP Survey Papers, 605: Series C. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/194098

Jovanović, V. (2016). The validity of the Satisfaction with Life Scale in adolescents and a comparison with single-item life satisfaction measures: A preliminary study. Quality of Life Research, 25(10), 3173–3180. https://doi.org/10.2307/44855775

Jovanović, V., & Lazić, M. (2020). Is longer always better? A comparison of the validity of single-item versus multiple-item measures of life satisfaction. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 15(3), 675–692. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9680-6

Kalmijn, M. (2017). Family structure and the well-being of immigrant children in four European countries. International Migration Review, 51(4), 927–963. https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12262

Karadag, M., & Gokcen, C. (2020, 2020/07/01). Does studying with the local students effect psychological symptoms in refugee adolescents? A controlled study. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00684-2

Karakayalı, J., zur Nieden, B., Groß, S., Kahveci, Ç., Güleryüz, T., & Heller, M. (2017). Die Beschulung neu zugewanderter und geflüchteter Kinder in Berlin. Praxis und Herausforderungen [The schooling of newly immigrated and refugee children in Berlin. Practice and challenges]. In Forschungsbericht. Forschungs-Interventions-Cluster "Solidarität im Wandel?". Berliner Institut für empirische Integrations- und Migrationsforschung (BIM), Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. https://www.bim.hu-berlin.de/media/Forschungsbericht_BIM_Fluchtcluster_23032017.pdf

Karakayalı, J., zur Nieden, B., Kahveci, Ç., Groß, S., & Heller, M. (2017). Die Kontinuität der Separation: Vorbereitungsklassen für neu zugewanderte Kinder und Jugendliche im Kontext historischer Formen separierter Beschulung [The continuity of separation: Preparatory classes for newly immigrated children and adolescents in the context of historical forms of separated schooling]. Die Deutsche Schule, 109(3), 223–235. https://www.waxmann.com/index.php?eID=download&id_artikel=ART102186&uid=frei

Kia-Keating, M., & Ellis, B. H. (2007). Belonging and connection to school in resettlement Young refugees, school belonging and psychosocial adjustment. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 12(1), 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104507071052

Kontopantelis, E., White, I. R., Sperrin, M., & Buchan, I. (2017). Outcome-sensitive multiple imputation: A simulation study. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 17(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-016-0281-5

Kovacev, L., & Shute, R. (2004). Acculturation and social support in relation to psychosocial adjustment of adolescent refugees resettled in Australia. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28(3), 259–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250344000497

Kroh, M., Kühne, S., Jacobsen, J., Siegert, M., & Siegers, R. (2017). Sampling, nonresponse, and integrated weighting of the 2016 IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees (M3/M4)–revised version. SOEP Survey Papers 477: Series C. Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung (DIW). http://hdl.handle.net/10419/172792

Lang, N. W. (2019). Teachers’ translanguaging practices and “safe spaces” for adolescent newcomers: Toward alternative visions. Bilingual Research Journal, 42(1), 73–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/15235882.2018.1561550

Lau, W., Silove, D., Edwards, B., Forbes, D., Bryant, R. A., McFarlane, A. C., Hadzi-Pavlovic, D., Steel, Z., Nickerson, A., Van Hooff, M., Felmingham, K. L., Cowlishaw, S., Alkemade, N., Kartal, D., & O’Donnell, M. (2018). Adjustment of refugee children and adolescents in Australia Outcomes from wave three of the Building a New Life in Australia study. BMC Medicine, 16(1), 157. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1124-5

Lohr, S. L. (2009). Sampling: design and analysis. Brooks/Cole.

Lustig, S. L., Kia-Keating, M., Knight, W. G., Geltman, P., Ellis, H., Kinzie, J. D., Keane, T., & Saxe, G. N. (2004). Review of child and adolescent refugee mental health. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(1), 24–36. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200401000-00012

Mang, J., Wagner, S., Gomolka, J., Schäfer, A., Meinck, S., & Reiss, K. (2019). Technische Hintergrundinformationen PISA 2018 [Technical background information PISA 2018]. https://mediatum.ub.tum.de/doc/1518258/1518258.pdf

Massumi, M. (2019). Migration im Schulalter. Systemische Effekte der deutschen Schule und Bewältigungsprozesse migrierter Jugendlicher [Migration at school age. Systemic effects of German school and coping processes of migrated adolescents]. Peter Lang. https://doi.org/10.3726/b15893

Massumi, M., von Dewitz, N., Grießbach, J., Terhart, H., Wagner, K., Hippmann, K., & Altinay, L. (2015). Neu zugewanderte Kinder und Jugendliche im deutschen Schulsystem [Newly immigrated children and adolescents in the German school system]. Mercator-Institut für Sprachförderung und Deutsch als Zweitsprache und Zentrum für LehrerInnenbildung der Universität zu Köln. https://www.mercator-institut-sprachfoerderung.de/fileadmin/Redaktion/PDF/Publikationen/MI_ZfL_Studie_Zugewanderte_im_deutschen_Schulsystem_final_screen.pdf

Masten, A. S., Burt, K. B., & Coatsworth, J. D. (2006). Competence and psychopathology in development. In D. Cicchetti & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Risk, disorder, and adaptation (pp. 696–738). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470939406.ch19

Matthews, J. (2008). Schooling and settlement: Refugee education in Australia. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 18(1), 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/09620210802195947

McNeely, C. A., Morland, L., Doty, S. B., Meschke, L. L., Awad, S., Husain, A., & Nashwan, A. (2017). How schools can promote healthy development for newly arrived immigrant and refugee adolescents: Research priorities. Journal of School Health, 87(2), 121–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12477

Mediendienst Integration. (2017, Dec 21). Wie viele neu zugewanderte Kinder gehen zur Schule? [How many newly immigrated children go to school?] https://mediendienst-integration.de/artikel/bildung-schule-neuzugewanderte-fluechtlinge-auslaendische-kinder.html

Michel, A., Titzmann, P. F., & Silbereisen, R. K. (2012). Psychological adaptation of adolescent immigrants from the former Soviet Union in Germany. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 43(1), 59–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022111416662

Miller, J., Mitchell, J., & Brown, J. A. (2005). African refugees with interrupted schooling in the high school mainstream: Dilemmas for teachers. Prospect, 20(2), 19–33. http://www.ameprc.mq.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/229802/20_2_2_Miller.pdf

Montgomery, E., & Foldspang, A. (2007). Discrimination, mental problems and social adaptation in young refugees. The European Journal of Public Health, 18(2), 156–161. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckm073

Motti-Stefanidi, F., Berry, J. W., Chryssochoou, X., Sam, D. L., & Phinney, J. S. (2012). Positive immigrant youth adaptation in context: Developmental, acculturation, and social-psychological perspectives. In A. S. Masten, K. Liebkind, & D. J. Hernandez (Eds.), The Jacobs Foundation series on adolescence. Realizing the potential of immigrant youth (pp. 117–158). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139094696.008

Nilsson, J., & Axelsson, M. (2013). “Welcome to Sweden”: Newly arrived students’ experiences of pedagogical and social provision in introductory and regular classes. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 6(1), 137–164. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1053606.pdf

OECD. (2013). PISA 2012 results: Ready to learn. Students’ engagement, drive and self-beliefs (Volume III). PISA, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264201170-en

OECD. (2020). Sense of belonging at school. In OECD (Ed.), PISA 2018 Results (Volume III): What school life means for students’ lives. PISA, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/d69dc209-en

Osterman, K. F. (2000). Students’ need for belonging in the school community. Review of Educational Research, 70(3), 323–367. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543070003323

Osterman, K. F. (2010). Teacher practice and students’ sense of belonging. In T. Lovat, R. Toomey, & N. Clement (Eds.), International research handbook on values education and student wellbeing (pp. 239–260). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-8675-4_15

Panagiotopoulou, J. A., & Rosen, L. (2018). Denied inclusion of migration-related multilingualism An ethnographic approach to a preparatory class for newly arrived children in Germany. Language and Education, 32(5), 394–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2018.1489829

Panagiotopoulou, J. A., Rosen, L., & Karduck, S. (2017). Exklusion durch institutionalisierte Barrieren. Einblicke in die pädagogische Praxis einer sogenannten Vorbereitungsklasse für geflüchtete Kinder und Jugendliche in einem marginalisierten Quartier von Köln [Exclusion through institutionalized barriers. Insights into the pedagogical practice of a so-called preparatory class for refugee children and adolescents in a marginalized neighborhood of Cologne]. In R. Ceylan, M. Ottersbach, & P. Wiedemann (Eds.), Neue Mobilitäts- und Migrationsprozesse und sozialräumliche Segregation. Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-18868-9_8

Panter-Brick, C., Grimon, M. P., & Eggerman, M. (2014). Caregiver-child mental health: A prospective study in conflict and refugee settings. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(4), 313–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12167

Pittman, L. D., & Richmond, A. H. (2007). Academic and psychological functioning in late adolescence: The importance of school belonging. The Journal of Experimental Education, 75(4), 270–290. https://doi.org/10.3200/JEXE.75.4.270-292

Porter, M., & Haslam, N. (2005). Predisplacement and postdisplacement factors associated with mental health of refugees and internally displaced persons: A meta-analysis. JAMA, 294(5), 602–612. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.294.5.602

Pugh, K., Every, D., & Hattam, R. (2012). Inclusive education for students with refugee experience Whole school reform in a South Australian primary school. Australian Educational Researcher, 39(2), 125–141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-011-0048-2

Richter, D., Rohrer, J., Metzing, M., Weinhardt, M., & Schupp, J. (2017). SOEP Scales Manual (updated for SOEP-Core v32.1). SOEP Survey Papers 423: Series C. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/156115

Robinson, M. D., & Clore, G. L. (2002). Belief and feeling: Evidence for an accessibility model of emotional self-report. Psychological Bulletin, 128(6), 934. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.128.6.934

Roeser, R. W., Eccles, J. S., & Sameroff, A. J. (2000). School as a context of early adolescents’ academic and social-emotional development: A summary of research findings. The Elementary School Journal, 100(5), 443–471. https://doi.org/10.1086/499650

Ryan, D., Dooley, B., & Benson, C. (2008). Theoretical perspectives on post-migration adaptation and psychological well-being among refugees: Towards a resource-based model. Journal of Refugee Studies, 21(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fem047

Salami, S. O. (2011). Personality and psychological well-being of adolescents: The moderating role of emotional intelligence. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 39(6), 785–794. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2011.39.6.785

Sam, D. L., Vedder, P., Ward, C., & Horenczyk, G. (2006). Psychological and sociocultural adaptation of immigrant youth. In J. W. Berry, J. S. Phinney, D. L. Sam, & P. Vedder (Eds.), Immigrant youth in cultural transition: Acculturation, identity, and adaptation across national contexts (pp. 117–141). https://doi.org/10.4324/9780415963619-5

Schachner, M. K., Juang, L., Moffitt, U., & van de Vijver, F. J. R. (2018). Schools as acculturative and developmental contexts for youth of immigrant and refugee background. European Psychologist, 23(1), 44–56. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000312

Schech, S. (2014). Silent bargain or rural cosmopolitanism? Refugee settlement in regional Australia. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 40(4), 601–618. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183x.2013.830882

Schipolowski, S., Edele, A., Mahler, N. & Stanat, P. (2021). Mathematics and science proficiency of young refugees in secondary schools in Germany. Journal of Educational Research Online, 13(1), 78–104. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:22066

Schmiedebach, M., & Wegner, C. (2019). Beschulung neuzugewanderter Schüler innen-Emotionales Empfinden in der Vorbereitungs- und Regelklasse [Schooling of newly immigrated students emotional-wellbeing in preparatory and regular classes]. Bildungsforschung, 1, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.25539/bildungsforschun.v0i1.270

Schotte, K., Stanat, P., & Edele, A. (2018). Is integration always most adaptive? The role of cultural identity in academic achievement and in psychological adaptation of immigrant students in Germany. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(1), 16–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0737-x

Shehadeh, A., Loots, G., Vanderfaeillie, J., & Derluyn, I. (2015). The impact of parental detention on the psychological wellbeing of Palestinian children. PLoS ONE, 10(7), e0133347. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0133347

Short, D. J., & Boyson, B. A. (2012). Helping newcomer students succeed in secondary schools and beyond. Center for Applied Linguistics. https://www.cal.org/resource-center/publications-products/helping-newcomer-students

Sirin, S. R., & Rogers-Sirin, L. (2015). The educational and mental health needs of Syrian refugee children. Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/FCD-Sirin-Rogers-FINAL.pdf

StataCorp. (2019). Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. StataCorp LLC.

Steel, Z., Chey, T., Silove, D., Marnane, C., Bryant, R. A., & Van Ommeren, M. (2009). Association of torture and other potentially traumatic events with mental health outcomes among populations exposed to mass conflict and displacement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA, 302(5), 537–549. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.1132

Steel, Z., Momartin, S., Silove, D., Coello, M., Aroche, J., & Tay, A. K. (2011). Two year psychosocial and mental health outcomes for refugees subjected to restrictive or supportive immigration policies. Social Science & Medicine, 72(7), 1149–1156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.007

Suárez-Orozco, C., Motti-Stefanidi, F., Marks, A., & Katsiaficas, D. (2018). An integrative risk and resilience model for understanding the adaptation of immigrant-origin children and youth. American Psychologist, 73(6), 781. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000265

Suldo, S. M., & Huebner, E. S. (2004). Does life satisfaction moderate the effects of stressful life events on psychopathological behavior during adolescence? School Psychology Quarterly, 19(2), 93. https://doi.org/10.1521/scpq.19.2.93.33313

Suldo, S. M., Minch, D. R., & Hearon, B. V. (2015). Adolescent life satisfaction and personality characteristics: Investigating relationships using a five factor model. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(4), 965–983. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9544-1

Suldo, S. M., Riley, K. N., & Shaffer, E. J. (2006). Academic correlates of children and adolescents’ life satisfaction. School Psychology International, 27(5), 567–582. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034306073411

Tajic, D., & Bunar, N. (2020). Do both ‘get it right’? Inclusion of newly arrived migrant students in Swedish primary schools. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2020.1841838

Taylor, S., & Sidhu, R. K. (2012). Supporting refugee students in schools: What constitutes inclusive education? International Journal of Inclusive Education, 16(1), 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110903560085

UNHCR. (2020). Global trends. Forced displacement in 2019. https://www.unhcr.org/5ee200e37.pdf

Vedder, P. H., & Horenczyk, G. (2006). Acculturation and the school. In D. L. Sam & J. W. Berry (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology (pp. 419–438). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511489891.031

Vervliet, M., Lammertyn, J., Broekaert, E., & Derluyn, I. (2014). Longitudinal follow-up of the mental health of unaccompanied refugee minors. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 23(5), 337–346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-013-0463-1