Abstract

In this paper, I analyze whether premium refunds can reduce ex-post moral hazard behavior in the health insurance market. I do so by estimating the effect of these refunds on different measures of medical demand. I use panel data from German sickness funds that cover the years 2006–2010 and I estimate effects for the year 2010. Applying regression adjusted matching, I find that choosing a tariff that contains a premium refund is associated with a significant reduction in the probability of visiting a general practitioner. Furthermore, the probability of visiting a doctor due to a trivial ailment such as a common cold is reduced. Effects are mainly driven by younger (and, therefore, healthier) individuals, and they are stronger for men than for women. Medical expenditures for doctor visits are also reduced. I conclude that there is evidence that premium refunds are associated with a reduction in ex-post moral hazard. Robustness checks support these findings. Yet, using observable characteristics for matching and regression, it is never possible to completely eliminate a potentially remaining selection bias and results may not be interpreted in a causal manner.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

I call the default tariff in the German SHI “full insurance” although it exhibits some kinds of co-payment as well, e.g., for drug prescriptions or hospital stays. However, these are identical for individuals in both tariffs.

ICD-10-GM refers to “International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, German Modification”.

These benefits are recorded in the Code of Social Law Book V (“Sozialgesetzbuch V”).

Each sickness fund has its own contribution rate which applies to both individuals in the default tariff as well as those in the premium refund tariff, and which is identical for both. As a contribution, 7.3% of the employee’s gross income is paid by the employer, the rest by the employee. For example, if the total contribution rate is 15.5% the insured pays 8.2%. If they earn 2000 euros gross per month, they pay a contribution of 164 euros each month. This is the amount a participant of the premium refund tariff may get back at the end of the year. For individuals in the default tariff, there is no premium refund at all.

For individuals that have been less than 365 days insured, the refund tariff works analogously: These individuals paid less insurance contribution in this year (e.g., only for 11 months) but they can still get a premium refund of 1/12 of their annual insurance contribution, i.e., the absolute value of the potential premium refund is lower.

Both sickness funds offer information on the premium refund tariff on their website. However, there was no additional information sent to the insured via newsletter.

In fact, in 2010 there were twice as many individuals enrolled in the deductible tariff compared to the premium refund tariff [21].

To condition on lagged outcomes and on some lagged covariates, I use the average of the years 2006–2008. Observations of the year 2009 are not used as control variables because individuals could anticipate their participation in 2010 and choose to antedate medical demands. This behavior was shown by Chandra et al. [7].

Imbens proposes pre-selecting variables that are assessed as being important according to economic theory. In addition, a set of variables is selected where it is not clear whether they should be included in the model. Each of these variables is tested by comparing a logistic regression of the treatment dummy on pre-selected variables with a logistic regression of the treatment dummy on pre-selected variables plus one of the variables that are to be tested. The variable where the likelihood ratio test statistic is the highest is included in the model. This procedure is repeated until the test statistic falls below some threshold. In line with Imbens [30], I use 1.00 as threshold value for linear terms and 2.71 for quadratic/interaction terms.

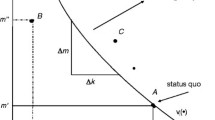

With an increasing degree of cost-sharing, insurance coverage becomes smaller because the sickness fund only pays for a smaller part of the costs.

For the estimation, I use the psmatch2 Stata command.

Another advantage of combining propensity score matching and regression is that by comparing the distribution of propensity scores between the two groups participants with no or very few controls can be excluded from the analysis (i.e., the data are trimmed). Thereby, the two groups can be made more similar.

“Other costs” comprise all remaining types of costs and are therefore very heterogeneous. They contain payments for rehabilitation, prevention courses, and home healthcare products, amongst others. When constructing the sum of “other costs” that occur in the sickness fund, I exclude premiums that were paid out to the insured for participating in the premium refund tariff or in a bonus program.

Here, a family consists of the insurance member and his or her co-insured family members. If there are no co-insured family members, the data remain at the individual level. Otherwise, they are condensed to the family level. If both spouses are insurance members (instead of one being the insurance member and one being co-insured), they are recorded separately in the data and not as one family.

See section “Identification and estimation” for the motivation of this approach.

This information has only been available since July 2008 and can therefore not be used for the matching process.

Among participants who received a premium refund, the average value of the premium refund is 294.44 euros (minimum 22.38 euros, at most 744.60 euros).

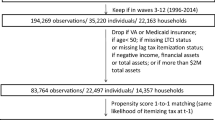

Treatment and control group were rather different with respect to the propensity score. Figure 2 in the “Appendix” shows the distribution of the untrimmed propensity score for the treatment and control group. Therefore, the data had to be trimmed relatively strongly. Figure 2 suggests trimming the data at propensity score = 0.1 because there are few observations in the control group with a propensity score higher than 0.1. Thereby, 8001 participants and 20,745 non-participants were excluded from the analysis. Since other authors may have decided differently on the trimming threshold, I will vary this threshold in the robustness checks.

Table 4 only shows the coefficients of interest, i.e., the treatment coefficient of each of the regressions run. Additional results are shown in the “Appendix” in Table 10 (linear coefficients of the propensity score estimation) and Table 11 (linear coefficients of the various regressions run in the main specification).

The youngest participant is 20 years old.

The oldest participant is 71 years old.

References

OECD: Focus on Health Spending. OECD Health Statistics 2015. https://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/Focus-Health-Spending-2015.pdf (2015). Accessed 20 March 2016

Schmitz, H.: More health care utilization with more insurance coverage? Evidence from a latent class model with German data. Appl. Econ. 44, 4455–4468 (2012)

Arrow, K.J.: Uncertainty and the welfare economics of medical care. Am. Econ. Rev. 53, 941–973 (1963)

Pauly, M.: The economics of moral hazard: comment. Am. Econ. Rev. 58, 531–537 (1968)

Manning, W.G., Newhouse, J.P., Duan, N., Keeler, E.B., Leibowitz, A.: Health insurance and the demand for health care. Evidence from a randomized experiment. Am. Econ. Rev. 77, 251–277 (1987)

Health Policy Brief: The Oregon health insurance experiment, Health Affairs (2015). https://doi.org/10.1377/hpb20150716.236899

Chandra, A., Gruber, J., McKnight, R.: Patient cost-sharing and hospitalization offsets in the elderly. Am. Econ. Rev. 100, 192–213 (2010)

Boes, S., Gerfin, M.: Does full insurance increase the demand for health care? Health Econ. 25, 1483–1496 (2016)

Farbmacher, H., Winter, J.: Per-period co-payments and the demand for health care: evidence from survey and claims data. Health Econ. 22, 1111–1123 (2013)

Farbmacher, H., Ihle, P., Schubert, I., Winter, J., Wuppermann, A.: Heterogeneous effects of a nonlinear price schedule for outpatient care. Health Econ. 26, 1234–1248 (2017)

Kunz, J.S., Winkelmann, R.: An econometric model of healthcare demand with non-linear pricing. Health Econ. 26, 691–702 (2017)

Felder, S., Werblow, A.: A physician fee that applies to acute but not to preventive care: evidence from a German deductible program. Schmollers Jahrbuch 128, 191–212 (2008)

Hemken, N., Schusterschitz, C., Thöni, M.: Optional deductibles in GKV (statutory German health insurance): do they also exert an effect in the medium term? J. Public Health 20, 219–226 (2012)

Pütz, C., Hagist, C.: Optional deductibles in social health insurance systems: findings from Germany. Eur. J. Health Econ. 7, 225–230 (2006)

Hayen, A., Klein, T.J., Salm, M.: Does the framing of patient cost-sharing incentives matter? The effects of deductibles vs. no-claim refunds. IZA DP 11508 (2018)

Gerfin, M., Kaiser, B., Schmid, C.: Healthcare demand in the presence of discrete price changes. Health Econ. 24, 1164–1177 (2015)

Aron-Dine, A., Einav, L., Finkelstein, A., Cullen, M.: Moral hazard in health insurance: do dynamic incentives matter? Rev. Econ. Stat. 97, 725–741 (2015)

Altonji, J.G., Elder, T.E., Taber, C.R.: Selection on observed and unobserved variables: assessing the effectiveness of catholic schools. J. Polit. Econ. 113, 151–184 (2005)

Oster, E.: Unobservable selection and coefficient stability: theory and evidence. Unpublished working paper. https://www.brown.edu/research/projects/oster/sites/brown.edu.research.projects.oster/files/uploads/Unobservable_Selection_and_Coefficient_Stability_0.pdf (2016). Accessed 21 Feb. 2019

Koç, Ç.: Disease-specific moral hazard and optimal health insurance design for physician services. J. Risk Insur. 78, 413–446 (2011)

GBE, Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes. https://www.gbe-bund.de (2015). Accessed 13 August 2015

Federal Statistical Office. https://www.destatis.de (2016). Accessed 6 February 2016

GKV head organization. https://www.gkv-spitzenverband.de (2016). Accessed 6 February 2016

Malin, E.M., Schmidt, E.M.: Beitragsrückzahlung in der GKV: ein Instrument zur Kostendämpfung? Die Betriebskrankenkasse 12(1995), 759–763 (1995)

Cutler, D.M., Finkelstein, A., McGarry, K.: Preference heterogeneity and insurance markets: explaining a puzzle of insurance. Am. Econ. Rev. Papers Proc. 98, 157–162 (2008)

Wooldridge, J.M.: Introductory econometrics: a modern approach, 6th edn. South Western Educational Publ, Mason (2015)

García Gómez, P., López Nicolás, A.: Health shocks, employment and income in the Spanish labour market. Health Econ. 15, 997–1009 (2006)

García-Gómez, P.: Institutions, health shocks and labour market outcomes across Europe. J. Health Econ. 30, 200–213 (2011)

Hagan, R., Jones, A.M., Rice, N.: Health and retirement in Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 6, 2676–2695 (2009)

Imbens, G.W.: Matching methods in practice: three examples. J. Hum. Resour. 50, 373–419 (2015)

Einav, L., Finkelstein, A., Ryan, S.P., Schrimpf, P., Cullen, M.R.: Selection on moral hazard in health insurance. Am. Econ. Rev. 103, 178–219 (2013)

Finkelstein, A., Arrow, K.J., Gruber, J., Newhouse, J.P., Stiglitz, J.E.: Moral hazard in health insurance, 1st edn. Columbia University Press, New York (2015)

Imbens, G.W., Wooldridge, J.M.: Recent developments in the econometrics of program evaluation. J. Econ. Lit. 47, 5–86 (2009)

Schmitz, H., Westphal, M.: Short- and medium-term effects of informal care provision on female caregivers’ health. J. Health Econ. 42, 174–185 (2015)

Marcus, J.: Does job loss make you smoke and gain weight? Economica 81, 626–648 (2014)

Caliendo, M., Kopeinig, S.: Some practical guidance for the implementation of propensity score matching. J. Econ. Surv. 22, 31–72 (2008)

Borghans, L., Golsteyn, B.H.H., Heckman, J.J., Meijers, H.: Gender differences in risk aversion and ambiguity aversion. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 7, 649–658 (2009)

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Hendrik Schmitz, Heiko Friedel, Michael Friedrichs, Stefanie Fritzenkötter, Daniel Kamhöfer, Stefan Pichler, and Matthias Westphal for valuable comments. Travel grants from the University of Paderborn and from DIBOGS (Duisburg-Ilmenau-Bayreuther Oberseminar zur Gesundheitsökonomik und Sozialpolitik e.V.) are gratefully acknowledged. This paper benefited from discussion at the CINCH Academy 2014 in Essen, the DIBOGS Workshop 2014 in Fürth, the Annual Conference DGGÖ 2015 in Bielefeld, the EEA Annual Meeting 2015 in Mannheim, and the Annual Meeting of the VfS 2015 in Münster. All errors are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

I am an employee of Team Gesundheit GmbH. Apart from that, there are no financial, ethical, or other potential conflicts of interests.

Human and animal rights statement

This article is based on previously available data, and does not involve any new studies of human subjects performed by the author. However, approvals from the sickness funds were obtained to use their data for this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thönnes, S. Ex-post moral hazard in the health insurance market: empirical evidence from German data. Eur J Health Econ 20, 1317–1333 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-019-01091-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-019-01091-w