Abstract

Many species of birds emit mobbing calls to recruit prey to join mobbing events. This anti-predator strategy often involves several species and, therefore, implies heterospecific communication. Some species of tit exhibit a sensitivity to allopatric mobbing calls, suggesting that heterospecific recognition is based on an innate component. To date, however, we have no information on whether the perception of allopatric calls varies with season, despite seasonality playing an important role in the perception of heterospecific call in some species. In this study, I investigate the responses of European great tits (Parus major) to the calls of a North American bird species, the black-capped chickadee (Poecile atricapillus), during two seasons: spring and in autumn (breeding and non-breeding seasons, respectively). Great tits approached the sound source during both seasons, with no significant difference in response between seasons. These findings indicate that season does not influence the response of birds to allopatric calls, and will help to shed light on the evolution of interspecific communication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Many species give alarm calls to warn about and defend against predators (Magrath et al. 2015). Usually, such alarm calls prompt receivers to flee or hide. Sometimes, prey produce mobbing calls to attract other individuals to join a mobbing flock and move towards the predator to drive it away (Pettifor 1990; Carlson et al. 2018). Paridae species (titmice, tits and chickadees) have been widely used to study the acoustic structure and social function of mobbing calls. Recent studies have revealed features in Paridae mobbing calls suggesting this system is more complex than was thought previously (Suzuki et al. 2016; Dutour et al. 2019a). Using such complex calls is likely to provide adaptive benefits to birds since they face a variety of predatory threats requiring complex behavioural responses.

Given that obtaining information about predators from these calls improves the survival of receivers (Griesser 2013) and that large mobs are more efficient than small mobs at driving the predator away (Robinson 1985; Krams et al. 2009), mobbing calls are not only used by conspecifics, but are used by heterospecifics as well (Hurd 1996; Dutour et al. 2016). Some Paridae species have been shown to respond to the mobbing calls of other Paridae species (Dutour et al. 2019a) and, in some cases, are also sensitive to the calls of allopatric species (Dutour et al. 2020; Salis et al. 2021a), suggesting that heterospecific recognition is based on an innate component.

Like many other vocalizations, the sensitivity to familiar mobbing calls can be affected by the season and the social context (Clucas et al. 2004, Dutour et al. 2019b, but see Scully et al. 2020). For instance, great tits (Parus major) responded more to heterospecific mobbing calls during autumn than they did during the breeding season (Dutour et al. 2019b). To my knowledge, however, it remains unknown whether sensitivity to allopatric mobbing calls is affected by seasonality.

Here, I used field playback experiments to investigate whether season influences European great tit responses to the mobbing calls given by North American black-capped chickadees (Poecile atricapillus). The mobbing behaviour of the great tit is well studied and previous research has shown they respond to mobbing calls of black-capped chickadees, making these species ideal candidates for this study (Randler 2012; Dutour et al. 2017, 2020). Specifically, I recorded the behavioural responses of great tits to black-capped chickadee calls during spring (breeding season) and autumn (non-breeding season).

Materials and methods

Study species and site

Data collection involved experimental playbacks conducted on wild great tits inhabiting forests located near Lyon (France). Playbacks of call and control treatments (see below for further details) were conducted during the breeding season (May 2021) and playbacks of calls were also undertaken in the non-breeding season (October 2021). Great tits are monogamous during the breeding season; however, they will form small conspecific groups, and often join heterospecific flocks, as autumn arrives (Saitou 1978; Ekman 1989; Carlson et al. 2020). Tests involved 45 different adult great tits (30 in spring and 15 in autumn). As the great tits in this study were unbanded, I kept a minimum distance of at least 200 m (m) between experimental sites to minimize the chance of testing the same individual more than once. This minimum distance has been used in previous studies to ensure independent testing in free-ranging great tits (Kalb et al. 2019; Dutour et al. 2021).

Playback stimuli

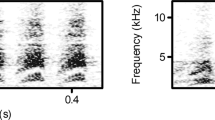

The fee-bee song of the black-capped chickadee was used as a control, to investigate whether great tits do indeed perceive black-capped chickadee calls as mobbing calls, and to ensure response was not due to novelty (i.e. that the great tits did not simply respond to any novel sound) (Randler 2012; Salis et al. 2021a). Black-capped chickadee mobbing calls and songs were obtained from the Macaulay Library (Cornell Lab of Ornithology) or from the Xeno Canto online databases. Sound clips were created using Avisoft-SASLab software. I created 15 unique sound tracks of mobbing calls, which were obtained from raw recordings of mobbing calls from 15 individuals. Mobbing calls were manipulated to obtain an equal number of eight D notes in each call. Calls were repeated in a sound file at a rate of 14 calls per minute. This frequency of notes and calls was chosen as they are known to elicit mobbing response in the great tit (see Randler 2012; Dutour et al. 2020). I obtained songs from 15 individuals and, from these raw recordings, created 15 unique sound clips of song for the control treatments. The fee-bee song consists of two notes that are produced in a stereotyped fashion (Ficken et al. 1978). Songs were repeated in a sound file at a rate of 14 songs per minute (Salis et al. 2021a).

Playback experiment

Once a focal bird was identified, a loudspeaker (Shopinnov 20 W, frequency response 100 Hz–15 kHz) was placed ~ 20 m from the bird. Prior to starting the experiment, the baseline behaviour of the focal bird was observed for at least 1 min during the pre-trial period. If the bird was found to show alarm behaviour during the pre-trial period, the test was abandoned. During playback, the target bird was considered to have responded positively to the test if it approached within a 10 m radius of the loudspeaker. This distance of approach has been used to assess the mobbing tendency of great tits in previous studies (Dutour et al. 2017, 2020). A preliminary analysis indicated that birds which approached the speaker (within a 10 m radius) were 3 times more likely to produce mobbing calls compared to individuals that did not approach. Furthermore, approaching birds also exhibited other mobbing behaviours (scanning, restless movements), however these behaviours were not measured in this study.

Data analysis

Data were analysed in R version 4.0.3. I used Fisher’s exact test to (i) compare mobbing responses between control and call treatments and (ii) test whether responsiveness of great tits to chickadee mobbing calls was influenced by the season.

Results

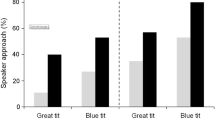

Great tits approached the loudspeaker during playback of chickadee calls more often than during playback of chickadee songs (Fisher’s exact test: p = 0.005; Fig. 1). There was no significant difference in response to chickadee calls (approaching behaviour) between the breeding and non-breeding seasons (Fisher’s exact test: p = 0.72; Fig. 1); nine of fifteen tits approached the loudspeaker in the breeding season compared to seven of fifteen in non-breeding season (Fig. 1).

Discussion

The results indicate that season does not influence the response of birds to allopatric calls. Great tits approached the sound source during both seasons and there was no significant difference in response between seasons. It is important to note, however, that a much bigger sample size is required to definitively support the null hypothesis (failure to reject the null hypothesis in this case is a long way from supporting the null) and to gather enough certainty about what the data is showing. An approach response can be a result of either (i) great tits perceiving the chickadee call as a general heterospecific mobbing call, and so approach to determine if a predator is present, or (ii) approach may be due to the novelty of the call as it is produced by a species that is unfamiliar to the great tit. I found that great tits responded more strongly towards chickadee mobbing calls than towards the chickadee territorial song, suggesting that great tits perceive chickadee calls as mobbing calls and that their response is not due to novelty. These results corroborate findings in previous studies (Randler 2012; Salis et al. 2021a) and indicated that great tits view chickadee call as a mobbing call. It would be of interest to compare the response of great tits to mobbing calls from conspecifics versus mobbing calls of allopatric species. I previously found that the responses of great tits to conspecific mobbing calls were similar to those expressed in response to mobbing calls emitted by chickadees, indicating that great tits extract information equivalent to their own mobbing calls (Dutour et al. 2017, 2020).

There is one main possible explanation why the response of great tits to allopatric calls is not influenced by the season: great tits could generalize responses from conspecific calls to allopatric calls that are acoustically similar (Ghirlanda and Enquist 2003; Sturdy et al. 2007). Such a hypothesis might explain these results as there is suggestion of acoustic similarity between the mobbing calls of great tits and black-capped chickadees calls (Dutour et al. 2017), and because season does not influence the response of great tits to conspecifics mobbing calls (respectively, 50% and 65% of great tits approached the loudspeaker during playbacks of mobbing calls in spring and winter; Salis et al. 2021b). In contrast, however, results of a recent study indicated that great tit and black-capped chickadee mobbing calls are indeed dissimilar (Dutour et al. 2020). Future studies are needed to gain further insight into the perception of allopatric calls and the generalization process in great tits.

My findings are in line with previous studies looking at the approaching behaviour of great tits in response to black-capped chickadee mobbing calls during spring (Randler 2012; Dutour et al. 2017, 2020; Salis et al. 2021a). This study’s result does, however, contradict the findings of a previous study which found an increased mobbing intensity in autumn at the heterospecific communication level (Dutour et al. 2019b). Together, these results suggest that great tits may respond more to sympatric heterospecific calls during the non-breeding season because they have an increased number of opportunities to learn to associate these calls with predatory threats when they form mixed-species flocks at this time of year.

In the present study, I investigated the mobbing behaviour of great tits during only two seasons of the year. Consequently, the study is somewhat limited as I was not able to take into account the responses of the great tits during winter, when predatory pressure is higher. In addition, I investigated variation in response between seasons; however, it would be of interest to investigate variation within season since some studies have documented a temporal intensification in mobbing behaviour during the breeding period (Montgomerie and Weatherhead 1988; Redondo 1989).

It has been suggested that great tits may be more effective in discriminating unfamiliar calls in winter, consequently leading to high scanning behaviour and low approaching behaviour toward unfamiliar calls (Salis et al. 2021b). My results show that this is not the case in autumn, although future work should measure other behavioural variables such as scanning, wing flicking, tail flit or calling in order to provide a more reliable overview of the response of the birds (Cully and Ligon 1976; Salis et al. 2021a).

Availability of data and material

The raw data are available as a Supplemental File.

References

Carlson NV, Healy SD, Templeton CN (2018) Mobbing. Curr Biol 28:R1081–R1082

Carlson NV, Healy SD, Templeton CN (2020) What makes a ‘community informant’? Reliability and anti-predator signal eavesdropping across mixed-species flocks of tits. Anim Behav Cogn 7:214–246

Clucas BA, Freeberg TM, Lucas JR (2004) Chick-a-dee call syntax, social context, and season affect vocal responses of carolina chickadees (Poecile carolinensis). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 55:187–196

Cully JF, Ligon JD (1976) Comparative mobbing behavior of Scrub and Mexican Jays. Auk 93:116–125

Dutour M, Lena JP, Lengagne T (2016) Mobbing behaviour varies according to predator dangerousness and occurrence. Anim Behav 119:119–124

Dutour M, Léna JP, Lengagne T (2017) Mobbing calls: a signal transcending species boundaries. Anim Behav 131:3–11

Dutour M, Lengagne T, Léna JP (2019a) Syntax manipulation changes perception of mobbing call sequences across passerine species. Ethology 125:635–644

Dutour M, Cordonnier M, Léna M, Lengagne T (2019b) Seasonal variation in mobbing behavior of passerine birds. J Ornithol 160:509–514

Dutour M, Suzuki TN, Wheatcroft D (2020) Great tit responses to the calls of an unfamiliar species suggest conserved perception of call ordering. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 74:1–9

Dutour M, Kalb N, Salis A, Randler C (2021) Number of callers may affect the response to conspecific mobbing calls in great tits (Parus major). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 75:29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-021-02969-7

Ekman J (1989) Ecology of non-breeding social systems of Parus. Wilson Bull 101:263–288

Ficken MS, Ficken RW, Witkin SR (1978) Vocal repertoire of the black-capped chickadee. Auk 95:34–48

Ghirlanda S, Enquist M (2003) A century of generalization. Anim Behav 66:15–36

Griesser M (2013) Do warning calls boost survival of signal recipients? Evidence from a field experiment in a group-living bird species. Front Zool 10:49–53

Hurd CR (1996) Interspecific attraction to the mobbing calls of black capped chickadees (Parus atricapillus). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 38:287–292

Kalb N, Anger F, Randler C (2019) Great tits encode contextual information in their food and mobbing calls. Royal Soc Open Sci 6:191210

Krams I, Bērziņš A, Krama T (2009) Group effect in nest defence behaviour of breeding pied flycatchers, Ficedula hypoleuca. Anim Behav 77:513–517

Magrath RD, Haff TM, Fallow PM, Radford AN (2015) Eavesdropping on heterospecific alarm calls: from mechanisms to consequences. Biol Rev 90:560–586

Montgomerie RD, Weatherhead PJ (1988) Risk and rewards of nest defence by parent birds. Q Rev Biol 63:167–187

Pettifor RA (1990) The effects of avian mobbing on a potential predator, the European kestrel, Falco tinnunculus. Anim Behav 39:821–827

Randler C (2012) A possible phylogenetically conserved urgency response of great tits (Parus major) towards allopatric mobbing calls. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 66:675–681

Redondo T (1989) Avian nest defence: theoretical models and evidence. Behaviour 111:161–195

Robinson SK (1985) Coloniality in the yellow-rumped cacique as a defense against nest predators. Auk 102:506–519

Saitou T (1978) Ecological study of social organization in the great tit, Parus major L.:I. Basic structure of the winter flocks. Jpn J Ecol 28:199–214

Salis A, Léna JP, Lengagne T (2021a) Great tits (Parus major) adequately respond to both allopatric combinatorial mobbing calls and their isolated parts. Ethology 127:213–222

Salis A, Lengagne T, Léna JP, Dutour M (2021b) Biological conclusions about importance of order in mobbing calls vary with the reproductive context in Great Tits (Parus major). Ibis 163:834–844

Scully EN, Campbell KA, Congdon JV, Sturdy CB (2020) Discrimination of black-capped chickadee (Poecile atricapillus) chick-a-dee calls produced across seasons. Anim Behav Cogn 7:247–256

Sturdy CB, Bloomfield LL, Charrier I, Lee TTY (2007) Chickadee vocal production and perception: an integrative approach to understanding acoustic communication. In: Otter KA (ed) Ecology and behavior of chickadees and titmice: an integrated approach. Oxford University Press, Oxford U.K, pp 153–166

Suzuki TN, Wheatcroft D, Griesser M (2016) Experimental evidence for compositional syntax in bird calls. Nat Commun 7:10986

Acknowledgements

I thank Go Fujita and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments that greatly improved the manuscript. I am grateful to Sarah Walsh for English language checking.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. No funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

All tested great tits returned to normal activity relatively quickly after the playbacks, so I was confident that they were not unduly stressful. All applicable national guidelines for the use of animals were followed.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Dutour, M. Season does not influence the response of great tits (Parus major) to allopatric mobbing calls. J Ethol 40, 233–236 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10164-022-00752-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10164-022-00752-3