Abstract

In some vertebrates, sexually mature individuals delay dispersal from their natal sites. Delayed dispersers are known to help their parents in many species; however, few studies have investigated the behavior of delayed dispersers in carnivores. Male offspring of the Japanese badger, Meles anakuma, remain in their natal sites and share setts with their mothers well after reaching sexual maturation. In this study, we investigated the contribution of male delayed dispersers in den maintenance activities of digging and bedding at their setts from September to February between 2010 and 2018. We found that delayed dispersers contributed approximately 60 and 30% of digging and bedding tasks, respectively. Specifically, while digging was constantly performed throughout the surveyed period, efforts in bedding gradually increased from September to February. We also found that delayed dispersers occasionally performed digging and bedding simultaneously with their mothers and siblings. Mothers may allow the male offspring to remain in the natal sites because of their help with den maintenance. It is probably advantageous for the males to remain in a familiar environment and have access to resources until they become large and competitive enough to establish and defend their mates and their own territories. Digital video images related to the article are available at http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php?movieid=momo210707ma01a, http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php?movieid=momo210707ma02a, http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php?movieid=momo210707ma03a, http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php?movieid=momo210707ma04a, http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php?movieid=momo210707ma05a, http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php?movieid=momo210707ma06a and http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php?movieid=momo210707ma07a.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Natal dispersal in animals is defined as the movement of individuals away from their birthplace to new sites where they attempt to establish their territories for reproduction and foraging (Greenwood 1980; Clutton-Brock and Lukas 2012). The process and timing of natal dispersal differ among species and individuals within species. The proximate factors that are likely to cause natal dispersal are social structures, population density, mating systems, resource availability, intraspecific aggression, and individual physical conditions (Zimmermann et al. 2005).

In some vertebrates, some individuals remain in their natal territories after sexual maturation with the parents’ permission (i.e., delayed dispersal, Ekman and Griesser 2016). Although delayed dispersal is costly in terms of delayed reproduction and competition among siblings and parents, they often gain benefits in multiple ways. For example, they may receive care from their parents, including increased access to resources and protection from competitors and predators (Ekman et al. 2001). Remaining with their natal families results in the formation of larger conspecific groups in which the members (including the delayed dispersers) gain benefits from group living, such as thermoregulation, feeding facilitation, and reduced predation risk (Shen et al. 2017; Nelson-Flower et al. 2018). Moreover, as the natal territories include resources such as suitable foraging sites, shelters, and safe migration routes, remaining in natal sites could result in higher survival rates than establishing new territories (Sparkman et al. 2010). Delayed dispersers often help their parents raise siblings, thereby gaining indirect fitness benefits (Clutton-Brock and Manser 2016). The social behavior of delayed dispersers and their interactions with their parents and siblings have been extensively studied in group-living species, including the banded mongoose, Mungos mungo (Cant et al. 2016); Gray wolf, Canis lupus (Cassidy et al. 2017); African lion, Panthera leo (Packer et al. 1990, 1992, 2001); and European badger, Meles meles (Dugdale et al. 2010). However, the details of delayed disperser behavior have rarely been described in species that do not form large groups, such as most carnivores (Graw et al. 2016, 2019).

When the net benefits of dispersal differ between the sexes, sex-biased natal dispersal arises, in which case, one sex disperses further or more frequently than the other. Sex-biased dispersal is hypothesized to have evolved in association with a variety of factors, including mating systems, inbreeding avoidance, competition for mates, and competition for resources (Greenwood 1980; Smith et al. 2017). However, the correlation between these ecological factors and the direction of sex-biased dispersal is not necessarily consistent across species (Lawson Handley and Perrin 2007), suggesting the need for further studies. While male-biased dispersal is common in mammals, the opposite patterns have been rarely reported, except for some species, including chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and African wild dogs (Lycaon pictus) (McNutt 1996; Nishida et al. 2003). These exceptions provide valuable opportunities to investigate the evolutionary causes of sex-biased dispersal (Graw et al. 2016).

The Japanese badger, Meles anakuma, can be either solitary or forms groups consisting of several related individuals (Tanaka et al. 2002a; Kaneko et al. 2014). The mating system of Japanese badgers is socially polygynous, where territorial adult males occupy a wide range, including the territories of two or more adult females (Tanaka et al. 2002a; Kaneko et al. 2014). Only mothers care for offspring, and territorial adult males do not share setts with adult females and their own offspring. Although male Japanese badgers probably become sexually mature at around 24 months of age (Kaneko 2015), they remain in the natal area until 26–48 months of age and share setts with their mothers and siblings (< 1 year old) from September to February (Fig. 1; Tanaka et al. 2002a; Kaneko et al. 2014). Conversely, females reach sexual maturity at 12 months of age, after which they immediately disperse from their natal area (Fig. 1; Tanaka et al. 2002a; Kaneko et al. 2014). Japanese badgers form mother–offspring groups as social units (Kaneko et al. 2014; Kaneko 2015). The members in social units, except for a mother and delayed dispersers, are replaced every year as newborn cubs join and some offspring leave natal territories. Japanese badgers construct underground burrows, called setts. Breeding events such as parturition and lactation occur in the setts. Considering that badgers sometimes continue to engage in den maintenance (i.e., enlarging and constructing chambers, and replacing bedding materials) for approximately one hour (Tanaka, personal observation), den maintenance is probably a time- and energy-consuming activity. We predicted that delayed disperser males make a significant contribution to the den maintenance. To test this prediction, we investigated the roles of male delayed dispersers in den maintenance activities.

The timing of dispersal and breeding of female and male Japanese badgers (Meles anakuma). Males usually disperse from natal sites between the end of age 2 and the beginning of age 3 (shown as ‘normal type’), but some males disperse between the end of age 3 and the beginning of age 4 (shown as ‘latter type’)

Materials and methods

Study site

We studied a population of Japanese badgers in Yamaguchi City (34° 12′ N, 131° 30′ E), Western Honshu, Japan. The study area is approximately 7 km2, of which 70% was covered by forests and the remaining area was residential and agricultural land. The south and east corners were close to a national highway (Route 9), and the west corner was close to the Yamaguchi-Hagi road. The study site had more than 200 sets of Japanese badgers (Fig. 2). The climate of this area is that of a temperate rain forest, with average temperatures of 27.2 °C in summer (August) and 4.3 °C in winter (January), while mean annual precipitation is 1886.5 mm (weather.time-j.net/Climate/Chart/Yamaguchi 20200906). Tanaka et al. (2002a) have provided further details on the ecological characteristics of this site.

Study species

Japanese badgers are musteloid carnivores distributed in Honshu, Kyushu, and Shikoku, Japan. They inhabit woodlands at elevations ranging from 0 m to approximately 2000 m in the subalpine zone (Yamamoto 1997; Kaneko 2015; Tanaka 2015). The setts are safe resting and sleeping sites, and the center of social and reproductive activities from late February to early June. The setts are also refuges during the climatic extremes. In particular, badgers hibernate in setts to avoid cold and wet conditions from mid-December to mid-February (Tanaka et al. 2002a, b; Tanaka 2005, 2006; Roper 2010). Mothers mate immediately after parturition, but do not implant until January to February of the following year (i.e., delayed implantation). Parturition occurs from late February to early April, and lactation continues for approximately three months after parturition (Tanaka 2002; Tanaka et al. 2002a; Kaneko 2015).

Field methods

We used motion-triggered video cameras with infrared flash (Primos Truth Cam 35, USA; Wildgame Model # W5EGC, USA; Bushnell Trophy Cam, USA; Keep Guard KG-550 PB, China; Ltl-Acorn 6210, China; Ltl-Acorn 6310 W, China) to monitor the behavior of Japanese badgers at their setts from 2010 to 2018, between September and February months. We programmed the cameras to record a 30- or 60-s video at each trigger with a 0–5-s delay before becoming active again (Allen et al. 2014, 20172017). Most of the surveyed setts had multiple entrances. The entrances of single setts were located near each other (1–4 m between entrances) (Fig. S1). We set one camera for each sett and confirmed that all the entrances of the focal sett were within the field of view of the cameras. The sensitivity was high enough that small rodents could be monitored, which guarantees that almost all movements of badgers were recorded.

We quantified the contribution of mothers and male offspring (delayed dispersers) to the digging and bedding collection. For each sett, we determined the duration and number of bouts of digging and bedding collection (Stewart et al. 1999). A bout of digging was defined as the behavioral sequence from initiation of digging (e.g., digging at the setts’ entrance, or bringing soil to the outside of the setts) to its termination (e.g., exiting from setts or disappearance into the setts). A bout of bedding was defined as the behavioral sequence from initiation of bedding collection (e.g., bringing bedding materials back to the setts) to its termination (e.g., exiting from setts or disappearance into the setts) (Stewart et al. 1999).

We determined the sex of the offspring and classified the developmental stages of the offspring into two age categories, cub (the first 12 months of life) and young adults (more than 13 months old) according to the position of the genital organs, relative body size, and external physical characteristics (Tanaka et al. 2002a; Kaneko 2015; Tanaka 2015). The identity of individuals was determined by the contours of the face, twin stripe patterns on the face (Fig. S2), and the relative body size to the adult female of the focal sett. Some individuals may have been monitored across multiple years. However, we always assigned another identity to each individual every year because the characteristics for identification changed in the following breeding season, which made individual identification difficult. Den maintenance activities of cubs were excluded from all analyses.

Behavioral analyses

When digging and bedding were performed by one individual, digging and bedding rate was determined as the number of bouts of digging and bedding collection of each individual per camera trap day. The duration of each individual’s digging or bedding collection activity was expressed as time (min) per camera trap day in each sett. As the efforts in den maintenance may change throughout the study period, the mean number and mean duration of the bouts per camera trap day were calculated monthly. The monthly bouts and duration of individuals per camera trap day were used for the following statistical analyses.

When digging and bedding were simultaneously performed by two or more individuals, we had to assume that each individual contributed equally to the task because it was impractical to quantify each individual’s effort. Therefore, we divided the number of digging and bedding bouts by the number of individuals involved in the focal bout. However, the duration of simultaneous digging and bedding was not divided by the number of individuals because we assumed that the individuals spent their time on the task, regardless of whether the task was performed with other individuals.

In some setts, some of the members of the focal social units were rarely recorded during the observation periods possibly because they mainly used some undiscovered sett. The individuals whose capture frequency (number of days recorded per camera trap day) was less than 0.1 (Table S1) were excluded from the analyses.

Statistical analyses

To test the effects of sex and month on den maintenance behavior, we used linear mixed models (LMMs) in which digging/bedding duration or digging/bedding rate of occurrence was included as the response variable, sex, month, and their interaction as explanatory variables, and identity of individuals and identity of social unit as random effects. A social unit was defined as a female’s family (mother and young adults). Young adults and females using setts alone were also defined as social units (Table S1). The identity of social units was always changed every breeding season, even if the same individual was observed across multiple years. Statistical analyses were performed using the R ver. 3.6.3 (R Developmental Core Team 2019).

Results

We conducted observational studies for 2716 days between September and February from 2010 to 2018. We monitored 25 social units (Table S1) and 49 individuals (22 females and 27 males). The same setts were typically utilized across multiple years. The number of entrances of each sett was in the range of 1–5, and the mean number of individuals (including cubs) per social unit was 2.4 (SE 0.21) (range 0–1 for females, 0–2 for young adults, and 0–2 for cubs). All individuals categorized as ‘young adults’ were determined to be males. The members of the social units that were observed are listed in Table S1.

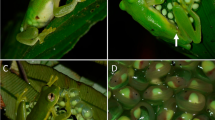

For digging, 212 bouts and 2565 min were recorded in total, while for bedding, 188 bouts and 1574 min were recorded in total. During digging, badgers made rapid movements with their forelimbs and claws to loosen the earth (Fig. 3a, http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php?movieid=momo210707ma01a,video 1). During bedding, badgers gathered fallen leaves, green leaves, and branches in bundles and brought the bedding materials into setts (Fig. 3b, http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php?movieid=momo210707ma02a, video 2).

Den maintenance behavior of the Japanese badger, Meles anakuma. a A male making rapid movements with its forelimbs and claws to loosen the earth during digging (http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php?movieid=momo210707ma01a, video 1). b A female gathering fallen leaves, green leaves, and branches in bundles and bringing the bedding materials into the sett (http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php?movieid=momo210707ma02a, video 2)

Male badgers contributed to 58.7% of the total bouts of digging and 55.9% of the total duration throughout the survey period (Fig. 4a, b). Digging rate and duration were not significantly different between the sexes and among months (Fig. 4a, b; Table S2). The interaction between sex and month was not significant (Fig. 4a, b; Table S2). Of the 25 social units, 2 (8.0%), 3 (12.0%), 4 (16.0%), and 16 (64.0%) social units consisted of solitary females, solitary young males, combination of a female and two young males, and combination of a female and a young male, respectively (Table S1). When only the social units that consisted of both male young adults and their mothers (n = 20 social units) were analyzed, male young adults contributed to 60.2% of the total bouts and 56.9% of the total duration of digging throughout the survey period.

Contribution of male and female Japanese badgers, Meles anakuma, to digging in each month (September–February) and throughout the study period (total). a Digging rate is the mean (+ standard error [s.e.]) number of digging bouts per individual and camera trap day. b Mean (+ s.e.) digging duration (min) per individual and camera trap day. In both a and b, data were pooled across years

Males contributed to 29.3% of the total bouts and 24.9% of the total duration of bedding (Fig. 5a, b). Bedding rate and duration were significantly higher for females than for young males (Fig. 5a, b; Table S2). Bedding rate and duration were significantly different among months, increasing from September to February (Fig. 5a, b; Table S2). There was no significant interaction between sex and month, suggesting that the seasonal changes in bedding rate and duration were similar between the sexes (Fig. 5a, b; Table S2). When only social units composed of both male young adults (single individual or multiple males) and their mothers were analyzed, male young adults contributed to 31.5% of the total bouts and 26.6% of the total duration of bedding throughout the survey period.

Contribution of male and female Japanese badgers, Meles anakuma, to bedding in each month (September to February) and throughout the study period (total). a Bedding rate is the mean (+ standard error [s.e.]) number of bedding bouts per individual and camera trap day. b Mean (+ s.e.) bedding duration (min) per individual and camera trap day. In both a and b, data were pooled across years

Among the 203 digging bouts recorded at the setts shared by both male young adults (single individual or multiple males) and their mothers, 52 bouts (25.6%) were simultaneously performed by multiple individuals. In these cases, the combinations were as follows: (i) mother and one male young adult (84.6%) (Fig. 6a, http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php?movieid=momo210707ma03a, video 3), (ii) two male young adults (11.5%) (Fig. 6b, http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php?movieid=momo210707ma04a, video 4), and (iii) a mother and two male young adults (3.9%) (Fig. 6c, http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php?movieid=momo210707ma05a, video 5). In case (ii), the pairs were presumed to be individuals of different ages based on their relative sizes. When simultaneous bedding occurred, each individual collected bedding materials and brought them into setts without division of roles in almost all cases (Fig. 7a, http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php?movieid=momo210707ma06a, video 6). However, in one pair (a mother and a male young adult), one badger carried the bedding materials to the entrance of the setts and the other carried it into the sett (Fig. 7b, http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php?movieid=momo210707ma07a, video 7).

Simultaneous digging by multiple individual Japanese badgers, Meles anakuma, a mother and a male offspring a (http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php?movieid=momo210707ma03a, video 3), two male offspring b (http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php?movieid=momo210707ma04a, video 4), and a mother and two male offspring c (http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php?movieid=momo210707ma05a, video 5). Notably, in c, a cub appeared out of the sett (the rightmost individual), but it did not partake in digging

Simultaneous bedding by two individual Japanese badgers, Meles anakuma. In a, each individual is collecting bedding materials and bringing them into the sett (http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php?movieid=momo210707ma06a, video 6). In b, a mother is carrying the bedding materials to the entrance of the sett and the male is carrying them into the sett (http://www.momo-p.com/showdetail-e.php?movieid=momo210707ma07a, video 7)

Discussion

The behavior of male delayed dispersers has rarely been explored in carnivores, particularly in species that do not form large groups (Graw et al. 2019). We investigated the roles of male delayed dispersers in the den maintenance activities of digging and bedding collection at their setts in Japanese badgers. Our results showed that male offspring contributed to digging and bedding as part of den maintenance with their mothers and siblings. As the contribution of male delayed dispersers into den maintenance was relatively large (especially for digging), mothers probably gained benefits with the help of the delayed dispersers in terms of den maintenance. The males who remain and utilize resources in the mother’s territory are her potential competitors. However, mothers may tolerate the delayed dispersal of male offspring because of their help with den maintenance. Given that mothers usually reproduce using the same setts at the end of winter (Tanaka 2002, 2006; Tanaka et al. 2002a), mothers with delayed dispersal would have greater reproductive success. Help from male offspring is not limited to den maintenance. The offspring continue to remain at their natal sites after overwintering. When cubs move out of the natal setts, male offspring are observed to engage in care behavior of cubs, such as following and grooming the cubs (Tanaka et al. unpublished data, see also Fig. S3 for an image of grooming).

Delayed disperser males probably have few chances of mating, given that dispersal is a necessary condition for the acquisition of a territorial male position and substantial mating success (Clutton-Brock and Manser 2016). Nevertheless, it is probably advantageous for them to remain in a familiar environment and have access to resources within their natal territory. In Japanese badgers, males are 1.3–1.4 times heavier than females (Kaneko 2015; Tanaka 2015), suggesting sexual selection for large male body sizes. Young males are relatively smaller and unlikely to physically defend their mates against rival males. After reaching breeding age, male body size continues to increase (Sugianto et al. 2019); thus, male badgers may remain in their natal sites until they become large and competitive enough to establish and defend their mates and their own territories. Meanwhile, females disperse at an age of approximately 14 months, probably because they already have a high chance of breeding while they are young.

Delayed dispersers of Japanese badgers probably obtain other benefits than access to resources. For example, communal denning in winter would reduce the cost of thermoregulation during hibernation if multiple individuals are in the same chamber (Tanaka 2006). Furthermore, delayed dispersers are likely to gain indirect genetic benefits by helping their mothers (i.e., den maintenance and other cub-care behaviors mentioned above). More studies are needed to elucidate the benefits that delayed dispersers gain and selective forces that favor male delayed dispersal in this species.

While males of Japanese badgers remain in their natal territory for a few years, other carnivores in which delayed dispersal occurs typically remain in their natal sites for more years or even never disperse (i.e., natal philopatry), leading to the formation of kin-based cooperative breeding systems consisting of more than ten individuals (Cant et al. 2016; Clutton-Brock and Manser 2016). This is true for some populations of the congeneric species European badgers M. meles, which form groups with a social hierarchy (Hewitt et al. 2009). In European badgers in North Wales, the majority of offspring of both sexes remain in their natal sites for several years (Dugdale et al. 2010). The contribution of delayed dispersers to den maintenance is distinctively different from that of Japanese badgers; neither sexes of delayed dispersers of European badgers perform digging and bedding, which are performed by individuals with high social status (usually large individuals) of both sexes (Stewart et al. 1999). Further comparison of the detailed social behavior of delayed dispersers would provide insights into the evolutionary processes of the diverse social systems of Meles.

Change history

15 December 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10164-022-00774-x

References

Allen ML, Wittmer HU, Wilmers CC (2014) Puma communication behaviours: understanding functional use and variation among sex and age classes. Behaviour 151:819–840

Allen ML, Gunther MS, Wilmers CC (2017) The scent of your enemy is my friend? The acquisition of large carnivore scent by a smaller carnivore. J Ethol 35:13–19

Cant MA, Nichols HJ, Thompson FJ, Vitikainen E (2016) Banded mongooses: demography, life history, and social behavior. In: Koenig WD, Dickinson JL (eds) Cooperative breeding in vertebrates. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 318–337

Cassidy KA, Mech LD, MacNulty DR, Stahler DR, Smith DW (2017) Sexually dimorphic aggression indicates male gray wolves specialize in pack defense against conspecific groups. Behav Processes 136:64–72

Clutton-Brock TH, Lukas D (2012) The evolution of social philopatry and dispersal in female mammals. Mol Ecol 21:472–492

Clutton-Brock TH, Manser MB (2016) Meerkats: cooperative breeding in the Kalahari. In: Koenig WD, Dickinson JL (eds) Cooperative breeding in vertebrates. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 294–317

Dugdale HL, Ellwood SA, Macdonald DW (2010) Alloparental behaviour and long-term costs of mothers tolerating other members of the group in a plurally breeding mammal. Anim Behav 80:721–735

Ekman J, Griesser M (2016) Siberian jays: delayed dispersal in the absence of cooperative breeding. In: Koenig WD, Dickinson JL (eds) Cooperative breeding in vertebrates. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 6–18

Ekman J, Eggers S, Griesser M, Tegelstrom H (2001) Queuing for preferred territories: delayed dispersal of Siberian jays. J Anim Ecol 70:317–324

Graw B, Lindholm AK, Manser MB (2016) Female-biased dispersal in the solitarily foraging slender mongoose, Galerella sanguinea, in the Kalahari. Anim Behav 111:69–78

Graw B, Kranstauber B, Manser MB (2019) Social organization of a solitary carnivore; spatial behaviour, interactions and relatedness in the slender mongoose. R Soc Open Sci 6:182160

Greenwood PJ (1980) Mating systems, philopatry and dispersal in birds and mammals. Anim Behav 28:1140–1162

Hewitt SE, Macdonald DW, Dugdale HL (2009) Context-dependent linear dominance hierarchies in social groups of European badgers, Meles meles. Anim Behav 77:161–169

Kaneko Y, Kanda E, Tashima S, Masuda R, Newman C, Macdonald DW (2014) The socio-spatial dynamics of the Japanese badger (Meles anakuma). J Mammal 95:290–300

Kaneko Y (2015) Meles anakuma Temminck 1842. In: Ohdachi SD, Ishibashi Y, Iwasa MA, Fukui D, Saitoh T (eds) The wild mammals of Japan, 2nd edn. Shoukadoh Book Sellers, Kyoto, pp 266–268

Lawson Handley LJ, Perrin N (2007) Advances in our understanding of mammalian sex-biased dispersal. Mol Ecol 16:1559–1578

McNutt JW (1996) Sex-biased dispersal in African wild dogs, Lycaon pictus. Anim Behav 52:1067–1077

Nelson-Flower MJ, Wiley EM, Flower TP, Ridley AR (2018) Individual dispersal delays in a cooperative breeder: ecological constraints, the benefits of philopatry and the social queue for dominance. J Anim Ecol 87:1227–1238

Nishida T, Corp N, Hamai M, Hasegawa T, Hiraiwa-Hasegawa M, Hosaka K, Hunt KD, Itoh N, Kawanaka K, Matsumoto-Oda A, Mitani JC, Nakamura M, Norikoshi K, Sakamaki T, Turner L, Uehara S, Zamma K (2003) Demography, female life history, and reproductive profiles among the chimpanzees of Mahale. Am J Primatol 59:99–121

Packer C, Scheel D, Pusey AE (1990) Why lions form groups: food is not enough. Am Nat 136:1–19

Packer C, Lewis S, Pusey AE (1992) A comparative analysis of non-offspring nursing. Anim Behav 43:265–281

Packer C, Pusey AE, Eberly LE (2001) Egalitarianism in female African lions. Science 293:690–693

Roper TJ (2010) Badger. HarperCollins Publishers, London

Shen SF, Emlen ST, Koenig WD, Rubenstein DR (2017) The ecology of cooperative breeding behavior. Ecol Lett 20:708–720

Smith JE, Lacey EA, Hayes LD (2017) Sociality in non-primate mammal. In: Rubenstein DR, Abbot P (eds) Comparative social evolution. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 284–319

Sparkman AM, Adams JR, Steury TD, Waits LP, Murray DL (2010) Direct fitness benefits of delayed dispersal in the cooperatively breeding red wolf (Canis rufus). Behav Ecol 22:199–205

Stewart PD, Bonesi L, Macdonald DW (1999) Individual differences in den maintenance effort in a communally dwelling mammal: the Eurasian badger. Anim Behav 57:153–161

Sugianto NA, Newman C, Macdonald DW, Buesching CD (2019) Heterochrony of puberty in the European badger (Meles meles) can be explained by growth rate and group-size: evidence for two endocrinological phenotypes. Plos one 14:e0203910

Tanaka H (2002) Ecology and social system of the Japanese badger, Meles meles anakuma (Carnivora; Mustelidae) in Yamaguchi, Japan. PhD thesis. University of Yamaguchi, Yamaguchi (in Japanese with English abstract)

Tanaka H (2005) Seasonal and daily activity patterns of Japanese badgers (Meles meles anakuma) in Western Honshu, Japan. Mamm Stud 30:11–17

Tanaka H (2006) Winter hibernation and body temperature fluctuation in the Japanese badger, Meles meles anakuma. Zool Sci 23:991–997

Tanaka H (2015) Japanese badger Meles anakuma. In: Seki Y, Enari H, Kodera Y, Tuji Y (eds) Field research methods for wildlife management. Kyoto University Press, Kyoto, pp 123–145 (in Japanese)

Tanaka H, Yamanaka A, Endo K (2002a) Spatial distribution and sett use by the Japanese badger, Meles meles anakuma. Mamm Stud 27:15–22

Tanaka H, Yamanaka A, Endo K (2002b) Female reproduction and characteristics breeding sett of Japanese badger Meles meles anakuma, in western Honshu, Japan. Information 5:481–490

Yamamoto Y (1997) Home range of Meles meles anakuma in Mt. Nyukasa, Nagano Prefecture, Japan. Nat Environ Sci Res 10:66–71 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Zimmermann F, Breitenmoser-Würsten C, Breitenmoser U (2005) Natal dispersal of Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) in Switzerland. J Zool 267:381–395

Acknowledgements

We thank the priest of Noda Shrine, the chief priests of Shunryu Temple, Jinpuku Temple, Myoki Temple, Joei Temple, Homyoin Temple, and Zuiyo Temple for their permission to perform fieldwork and for the provision of information. We would also like to thank the members of the Applied Animal Ecology Laboratory at the Faculty of Agriculture, Yamaguchi University, for supporting every stage of the fieldwork.

Funding

The study was partly financed by the Yamaguchi Prefecture Environmental Conservation Activities Grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HT designed the study. HT, YF, EY, YO and EH collected the data. HT, YO, EH and WK analyzed the data. HT and WK prepared the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed. This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised due to a retrospective Open Access order.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 Video1. A male offspring (delayed disperser) of the Japanese badger, Meles anakuma, digging the sett and scraping soil out (75.9MB, 00:00:24). Shot Date: 2016/12/29. Shot Location: Hananoki, Miyano, Yamaguchi City, Yamaguchi, Japan. Other information: The use of an infrared camera. Species: Meles anakuma. Key Words: Den maintenance, Digging, Delayed disperser, Male offspring (MOV 77811 KB)

Supplementary file2 Video 2. A mother Japanese badger, Meles anakuma, collecting fallen leaves for nesting materials and bringing them into the sett (88.7MB, 00:00:17). Shot Date: 2018/11/03. Shot Location: Ryuge, Miyano, Yamaguchi City, Yamaguchi, Japan. Species: Meles anakuma. Key Words: Den maintenance, Bedding, Mother (MOV 90899 KB)

Supplementary file3 Video 3. A male Japanese badger offspring, Meles anakuma, and his mother entering the sett together to dig the burrow by scraping the soil from the inside and carrying it out of the sett (80.5MB, 00:00:25). Shot Date: 2016/11/17. Shot Location: Era, Oodono, Yamaguchi City, Yamaguchi, Japan. Other information: The use of an infrared camera. Species: Meles anakuma. Key Words: Den maintenance, Simultaneous digging, Mother, Male offspring (MOV 82434 KB)

Supplementary file4 Video 4. Two male Japanese badgers (Meles anakuma) offspring digging together. One dug inside the sett and the other carried the soil and nesting materials from the inside to the outside of the sett (75.5MB, 00:00:24). Shot Date: 2014/11/10. Shot Location: Ryuge, Miyano, Yamaguchi City, Yamaguchi, Japan. Other information: The use of an infrared camera. Species: Meles anakuma. Keywords: Den maintenance, Simultaneous digging, Sibling, Male offspring, Delayed disperser (MOV 77358 KB)

Supplementary file5 Video 5. Three Japanese badgers, Meles anakuma, digging together in the sett. A mother badger entered the sett and dug out the soil, and two male offspring carried the scraped soil and nesting materials out of the sett. The cub present did not partake in the digging (92.6MB, 00:00:24). Shot Date: 2014/11/12. Shot Location: Ryuge, Miyano, Yamaguchi City, Yamaguchi, Japan. Species: Meles anakuma. Key Words: Den maintenance, Simultaneous digging, Sibling, Male offspring, Mother (MOV 94897 KB)

Supplementary file6 Video 6. A mother Japanese badger (Meles anakuma) bringing fallen leaves as nesting materials in the sett, followed by a male offspring bringing tree branches as nesting materials into the sett (93.5MB, 00:00:25). Shot Date: 2016/01/04. Shot Location: Hananoki, Miyano, Yamaguchi City, Yamaguchi, Japan. Other information: The use of an infrared camera. Species: Meles anakuma. Key Words: Den maintenance, Simultaneous bedding, Male offspring, Mother (MOV 95829 KB)

Supplementary file7 Video 7. A mother Japanese badger (Meles anakuma) collecting fallen leaves as nesting materials and carrying them to the entrance of the sett before a male offspring carried them into the sett (94.5MB, 00:00:29). Shot Date: 2014/12/26. Shot Location: Ryuge, Miyano, Yamaguchi City, Yamaguchi, Japan. Other information: The use of an infrared video camera. Species: Meles anakuma. Key Words: Den maintenance, Simultaneous bedding, Male offspring, Mother (MOV 96793 KB)

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Tanaka, H., Fukuda, Y., Yuki, E. et al. Cooperative den maintenance between male Japanese badgers that are delayed dispersers and their mothers. J Ethol 40, 3–11 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10164-021-00718-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10164-021-00718-x