Abstract

Little is known about the behaviors river otters (Lontra canadensis) commonly exhibit when visiting latrine sites. By use of video data we constructed an ethogram to describe and quantify latrine behaviors. The most common behaviors were standing (20.5 %) and sniffing (18.6 %), lending support to the hypothesis that latrines are used for olfactory communication. Surprisingly, defecation was rarely observed (1.4 %); body rubbing occurred more than defecation (10.5 %). It is possible that, in addition to feces, urine, and anal jelly, river otters use body rubbing to scent mark. To monitor site use, we determined seasonal, monthly, and daily visitation rates and calculated visit duration. River otters most frequently visited the latrine in the winter (December and January) but the longest visits occurred in the fall. Very few visits were recorded during the summer. Latrines were most often visited at night, but nocturnal and diurnal visit durations were not different. River otters were more likely to visit the latrine and engage in a specific behavior rather than travel straight through the site. Our data supported the idea that river otters are primarily solitary mammals, with most latrine visits by single otters. However, we documented groups of up to 4 individuals using the area, and group visits lasted longer than solitary visits. Therefore, whether visits are solitary or social, latrine sites are likely to act as communication stations to transmit information between individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Latrine behavior, the preferential use of a specific location for defecation (Irwin et al. 2004), is well documented within the Class Mammalia (Gorman and Trowbridge 1989). Latrine sites are crucial for the study of habitat selection, distribution, and occupancy of river otters (Dubuc et al. 1990; Newman and Griffin 1994; Swimley et al. 1998). Although latrines are believed to facilitate olfactory communication between individuals and/or groups (Brown and Macdonald 1985), several other hypotheses have been proposed regarding latrine communication, including transfer of information pertaining to territory boundaries (Roper et al. 1993), and health, social status, or reproductive state (reviewed by Brown and Macdonald 1985). Among river otters, olfactory latrine communication may aid species (Rostain et al. 2004) and social recognition (Oldham and Black 2009), communicate male social status (Rostain et al. 2004), or signal resource depletion (Kruuk 1992, 2006); overall function and use may vary with sex and social status (Ben-David et al. 2005).

To determine the function of river otter latrines, latrine behaviors of free-ranging river otters should be described and quantified. Rostain et al. (2004) and Hansen et al. (2009) described the behaviors of captive river otters, but the extent to which these observations represent the behaviors of river otters in their native home range is unclear. Study of latrine behavior will contribute to better understanding of the function of latrine sites and strengthen the basis of research methods that depend on latrine sites to reach conclusions about river otter populations.

The purpose of this study was to observe latrine-specific behaviors of North American river otters (Lontra canadensis) (Van Zyll de Jong 1987) to better understand the function of latrines. Given the difficulty of direct observation of river otters in the field, we characterized and quantified their latrine behavior by use of videos collected from camera traps (Bridges and Noss 2011). Currently, no data has been reported regarding behavioral patterns at latrine sites. The objectives of our study were:

-

1

to describe the latrine-specific behaviors of free-ranging river otters;

-

2

to quantify latrine behaviors; and

-

3

to assess the frequency and/or duration of solitary and social visits, and how these varied with ecological season and daily temperature variation.

Materials and methods

Field work

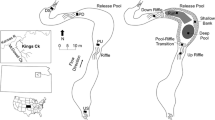

We used remote videography with night-vision capability to document the visitation patterns and behavior of river otters in east central Illinois from August 1, 2011 to August 31, 2012. We used SPYPOINT™ Pro-X digital game cameras to record the activity of the otters. When triggered, cameras recorded video data for 30–90 s with a minimum delay of 10 s between recordings. We visited cameras on a weekly to bi-weekly basis to collect and replace video storage cards, change batteries, evaluate the equipment, and check for otter sign.

Study site

The study site was within the Vermilion River Conservation Opportunity Area in Fairmount, Illinois, USA (UTM zone 16, 429788E 4437873 N/429752E 4437894 N). We selected two latrines less than 50 m apart on the basis of detection of river otter scat. Latrine 1 (2.0 m × 5.0 m) was located on a dam near a 1-acre fishpond; Latrine 2 (2.5 m × 6.5 m) was located on the south bank of the Salt Fork of the Vermilion River. An animal-made trail used by river otters connected the latrines. Because of the proximity and connectivity of the latrines, we believed these latrines to be used by a single population of otters and, therefore, combined data from both sites for this study.

Behavior assessment

We viewed all videos and identified those with otters present. We classified the recorded behaviors and evaluated group size, time of day, and duration of behavior. We used these videos for data analysis and to construct a detailed ethogram describing the observed behaviors. Within each video we used instantaneous scan sampling (5 s intervals) (Altmann 1974) to record group size and the behavior of each individual otter by use of our ethogram. We selected instantaneous scan sampling because it is systematic, quantitative, and appropriate for groups or individual animals, and because other researchers have successfully used the method (Stafford et al. 2012). For behaviors of particular interest (e.g., defecation at latrine sites), we re-evaluated the video data ad libitum (Altmann 1974) to improve the detail of events occurring around the behavior of interest. To assess the behaviors observed at latrines and identify the most common behavior, we calculated the total number of observations for each behavior type. The percentage of behavior events was calculated as the number of observations (i.e., events) of a specific type of behavior divided by the total number of all behavior events.

To determine whether river otters more often traveled through the latrine or actively engaged in a specific behavior at the latrine, we classified our ethogram behaviors into two categories, “walking” or “activity”. Behaviors were classified as “walking” if the otter(s) traveled directly through the latrine without stopping to engage in any other behavior during the entire video. Behaviors were classified as “activity” if the otter(s) stopped and engaged in any of the ethogram-defined activity behaviors at the latrine site. We calculated the number of visits categorized as “walking” or “activity” to determine whether both types of behavior occurred at the same frequency. We also calculated the duration of both types of visit.

We compared visits and durations of visits for solitary river otters and otter groups. We defined a group as ≥2 otters. We did not assume relationships between otters at any time during the study. Therefore, irrespective of relative body size, each observed otter was counted as an individual. None of the otters were individually marked or identified, and the otters lacked unique morphology that would enable recognition of an animal repeatedly visiting latrines. To determine whether solitary or social activity was more likely to occur at the latrine, we categorized visits into either single-otter visits (solitary) or group visits (social).

Site use

We estimated visitation rates on the basis of the number of otter sightings in the videos per working camera day (days the camera was capable of recording data). We counted every river otter that came into the latrine during a video recording. The presence of one or more otters in a single video recording was regarded as a single visit.

We defined duration as time spent in the latrine by a solitary otter or by a group of otters. We determined duration by counting the number of seconds that otters were in the latrine, starting when the otters came into the frame of view, and ending when the otters were no longer visible. All time during which river otters were not visible in the video was excluded from calculation of the duration.

To determine seasonal variation in latrine use, we divided the year into four ecological seasons (fall, summer, spring, and winter) on the basis of weather data collected from three weather stations situated equidistant from the study site. In the Midwest, daily temperatures can be highly variable, fluctuating by as much as 15 °C (Wendland 1994) making it difficult to select ecological seasons by use of temperature data. We therefore used a 7-day moving average of temperature data (average of the high and low for each day) and snowfall to determine ecological seasons. Fall was identified as consistent temperatures between 11 and 20 °C, ending with the first snowfall. Winter began with the first snowfall and ended with the last snowfall; during winter most temperatures were <10 °C. Spring began at the last snowfall and temperatures were consistently between 11 and 20 °C. Most summer temperatures were >20 °C. We calculated the visitation rate and the duration of visits for each season. To determine whether river otters spent the same amount of time at the latrines irrespective of month, we calculated the visitation rate and duration of visits each month and tested for monthly variation. To test for daily preferences in activity, we determined the number of visits and durations of nocturnal and diurnal river otter latrine visits. We defined a nocturnal visit as activity between sunset and sunrise, and a diurnal visit as activity between sunrise and sunset, on the basis of daily data from Calendar-365.com (http://www.calendar-365.com, last accessed November 16, 2012).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SAS v. 9.3 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA). Nonparametric analysis was used for datasets that did not fit normal distribution curves. We tested for significant differences between numbers of observations (diurnal/nocturnal, walk/active, solitary/social) by use of chi-squared tests (Proc FREQ). We tested for differences between visit durations and seasonal and monthly visitation rates by use of Kruskal–Wallis tests (Proc NPAR1WAY). Each previously mentioned test was independently tested and variables revealing an association at a significance level of 0.05 were regarded as significant.

Results

We recorded a total of 126 river otter visits and a total of 170 min of otter activity between August 1, 2011 and August 31, 2012. Cameras operated for 409 camera days. We recorded approximately 25 min of video on the camera placed at the river latrine and 145 min on the camera placed at the dam near the fishpond.

Behavior assessment

From the 170 min of video data we recorded 2207 behavior observations. There were 1623 of out-of-view (OV) observations, i.e. portions of video after river otters had exited latrines. OV observations were not included in the analysis. Many observations (n = 126) provided only partial views (PV) of the animals, when otter(s) were present in the latrine but visibility was obstructed by an inanimate object or only part of their body was in the frame of view. Because we could not describe their behavior with certainty, PV visits were included in calculations of visitation rate but excluded from behavior and duration analyses.

Use of the ethogram to describe behaviors (Table 1) revealed that the majority of river otter behaviors were standing (20.5 %) and sniffing (18.6 %; Fig. 1). We recorded eight (1.4 %) instances of defecating at latrines. We reviewed videos when defecation was noted by use of ad libitum sampling and found that stomping and defecation were often sequential behaviors (22 % of defecation events), meaning the animal stomped its hind feet before bowel evacuation (Table 2). We never observed the opposite sequence (i.e., defecation followed by stomping) but it was also common for stomping and defecation to occur simultaneously (17 % of defecation events). We observed one instance in which an animal defecated without stomping and one instance in which an animal stomped but did not defecate (Table 2). Although observed, feeding at latrines was uncommon (0.4 %). Group activities such as allogrooming (5.0 %) and wrestling (4.4 %) were observed, but mounting (0.4 %) was rare. Although walking behaviors were also common (travel head down 14.4 %; travel head up 11.1 %), river otters were more likely to engage in activity (n = 86) at a latrine rather than simply walking through (X 2 = 17.67, df = 1, P < 0.001). Standing, sniffing, body rubbing, and travel behaviors were observed in all seasons (Fig. 2). Stomping or defecation was observed in all seasons except summer (Fig. 2). River otters also spent more time at latrines when engaged in an activity (\(\bar {x}\) = 26.6 s, SE = 2.6) than when walking through the sites (\(\bar {x}\) = 7.3 s, SE = 2.0; Kruskal–Wallis H = 38.3, P < 0.001). The video cameras captured some vocalization (chirping and grunting) during a few (n = 4) visits when more than one river otter was present.

Seasonal percentages of types of behavior of Illinois North American river otters observed in latrines within Vermilion River Conservation Opportunity Area in east central Illinois from August 1, 2011 to August 31, 2012. Instances when animals were out of view or only partially in view were excluded

We recorded more latrine visits by solitary animals (n = 92) than by groups (n = 34) of river otters (X 2 = 26.70, P < 0.0001). However, the duration of visits when ≥2 otters were present (\(\bar {x}\) = 33.6 s, SE = 4.4) were longer than for solitary visits (\(\bar {x}\) = 15.6 s, SE = 2.1; Kruskal–Wallis H = 21.0, P < 0.0001).

Site use

The visitation rate for the entire study period was 0.447 visits per working camera day. The mean duration of otter activity was 20.5 s with the shortest duration being 1.0 s and the longest 90.0 s. The number of otter visits per functional camera day varied by month (Kruskal–Wallis H = 128.0, P < 0.0001; Fig. 3). Visits by solitary otters and groups followed a similar frequency trend over the study period. Visitation rates of otters peaked in December (visitation rate = 0.919) and January (visitation rate = 0.569). The visitation rate was lowest in May, June, July, and August (visitation rate = 0.042, 0.056, 0.071, and 0.000, respectively). We found no evidence of monthly duration differences (Kruskal–Wallis H = 17.7, P = 0.089; Fig. 4).

We recorded more nocturnal latrine visits (n = 93) than diurnal visits (n = 33; X 2 = 0.821, df = 1, P < 0.0001). However, durations of latrine visits were similar irrespective of time of day (nocturnal \(\bar {x}\) = 21.6 s, SE = 2.5; diurnal \(\bar {x}\) = 17.2 s, SE = 3.7; Kruskal–Wallis H = 0.82, P = 0.365).

On the basis of our definition of ecological seasons on the basis of temperature and snowfall data, fall occurred from September 6, 2011 through November 29, 2011; winter occurred from November 30, 2011 through March 5, 2012; spring occurred from March 6, 2012 through June 7, 2012; summer occurred from June 8, 2012 through August 31, 2012 (Fig. 5). The number of river otter visits per functional camera day varied seasonally, with peak visits during winter (Kruskal–Wallis H = 90.2, P < 0.0001; Fig. 3). Group and solitary visits followed the same seasonal trend with the highest visitation rate, 0.62, observed in winter (group = 0.16, single = 0.46) and the lowest visitation rate, 0.08, in summer (group = 0.02, single = 0.07), although there were fewer group visits than single visits in all seasons. The duration of latrine visits varied significantly by season (Kruskal–Wallis H = 7.78, P = 0.05). Time spent by otters in the latrines was nearly identical during the fall (n = 28, \(\bar {x}\) = 25.9 s, SE = 4.8) and spring (n = 10, \(\bar {x}\) = 26.0 s, SE = 5.9) and least during the summer (n = 5, \(\bar {x}\) = 11.8 s, SE = 9.1).

Discussion

Behaviors observed at latrines indicated that river otters are indeed using these areas to exchange information. Otters were more likely to come to the latrine and engage in a behavior, although they did, on occasion, travel through the latrine without stopping. When river otters did stop in the latrine, they were most often observed sniffing or standing, supporting the idea that they may be collecting olfactory information about other animals carried through the air (Eisenberg and Kleiman 1972). Wild-caught, captive otters displayed sniffing behavior when investigating experimentally placed feces (Rostain et al. 2004). Patterns in the sniffing behavior indicated that otters could discriminate species, sex, and social familiarity on the basis of feces (Rostain et al. 2004). The sniffing behavior included a description of a slight bobbing of the head and flaring of the nostrils if the animal was facing the camera (Rostain et al. 2004), behavior which we also observed in the latrines.

By definition, latrine sites are associated with feces and other secretions (e.g., urine, anal jelly) used for chemical communication (Eisenberg and Kleiman 1972; Irwin et al. 2004). On the basis of latrine use by other species, it is reasonable that river otters stop at latrines to deposit scat that would, in turn, communicate information to others. Surprisingly, few defecation events were observed during our study. At times it was difficult to discern what specific scent-marking event (defecation, urination, jelly deposition) was occurring on a video because of distance from the camera, the position of the animal, or the position of vegetation that obscured the view. For the same reasons, video was not a reliable source for noting the position of scat once deposited, precluding our ability to determine whether any animals over-marked existing scat.

Previous studies have used ethograms to experimentally assess behavior of river otters captured in the wild and held in captivity (Rostain et al. 2004; Hansen et al. 2009). Although the animals were held in a captive facility rather than in a natural habit, there was some similarity in the behaviors observed in these studies. Rostain et al. (2004) observed sniffing, grooming, wrestling, and scent marking, and Hansen et al. (2009) observed grooming, wrestling, and mounting. The description of defecation provided by Rostain et al. (2004) suggests defecation often is associated with a “raise and flicking of the tail”. We also noted river otters raised or moved their tail during defecation. However, otters in our study typically stomped their hind feet during defecation and the stomping may have caused the observed tail movement. In our study, use of instantaneous scan sampling resulted in separate recording of defecation and stomping events. When ad libitum sampling was used, we found that stomping and defecation were often associated, although once we observed defecation or stomping behavior alone. It is also important to note that it is possible that stomping was actually defecation that was indiscernible on video. Combining stomping and defecation as one behavior group increases the percentage of defecation observations to approximately 5 %. Although this is still a small proportion of overall behaviors observed, it does not rule out latrines as communication stations.

Scent-marking by river otters is known to be facilitated by the deposition of scat, urine, and anal jelly (Mason and Macdonald 1987; Melquist and Hornocker 1983; Oldham and Black 2009; Rostain et al. 2004). However, the otters may also scent mark by foot-stomping and body rubbing relying on glands located in the pads of their feet and ventral region. Eurasian river otters (Lutra lutra Brünnich 1771) scrape sand and vegetation into small piles, probably scent marking them with inter-digital scent glands (Kruuk 2006). Male North American river otters have pedal glands which are believed to function in sexual communication given the sexual dimorphism of the presence of the gland (Kruuk 2006). North American river otters in our study typically combined stomping and defecation but we were unable to determine the sex of the individuals and could not, therefore, assess whether both males and females stomp their hind feed when defecating.

It is unclear from the literature whether North American river otters also have ventral scent glands. Several species of mustelid, including the Eurasian river otter, are known to have both types of gland (Hutchings and White 2000; Kruuk 2006). Body rubbing is a well-established form of scent-marking among mustelids including stoats (Mustela ermine L. 1758), weasels (Mustela nivalis L. 1766), ferrets (Mustela furo), and honey badgers (Mellivora capensis) (Erlinge et al. 1982; Clapperton 1989; Begg et al. 2003). Erlinge et al. (1982) described body rubbing as animals rubbing the belly and front-lateral body regions against vegetation or bare ground. For some species, for example the African dwarf mongoose (Helogale undulata rufula), body rubbing extends to the side of the head to incorporate cheek glands (Rasa 1973). These glands, located between the eye and the ear, deposit a thin secretion on to the substrate (Rasa 1973). Eurasian otters also rub their cheeks on stones as a method of scent communication (Kruuk 2006). We observed river otters rubbing the head, neck, and body over 10 % of the time. Rubbing and rolling of North American river otters has also been described by Melquist and Hornocker (1983) although they attributed this behavior to grooming, to maintain fur insulation. However, animals rubbed and rolled on the grass or bare ground, often in locations associated with fecal marking (Melquist and Hornocker 1983). River otters in our study often combined body rubbing and rolling but often the otters would lower their body to the ground so that the ventral surface was in contact with the substrate. It is possible that this type of rubbing may function in scent marking. Combining body rubbing, defecation, and stomping as a group of olfactory scent marking behaviors makes scent marking the third most common behavior we observed (approximately 16 % of observations) after stand and sniff which composed 21 and 19 % of observations, respectively. Our observed distribution of behaviors supports the hypothesis of olfactory communication at latrine sites.

Chemical signals that persist long after an individual has left the area are important for information exchange among solitary animals. Interestingly, Eurasian river otters in Scotland, which tend to be solitary (Kruuk and Moorhouse 1991) had a preference for sprainting on river banks upwind from the river itself, indicating the importance of feces in intraspecific communication (Kruuk 2014). Although river otters are regarded as more social than most mustelids (Liers 1951; Melquist and Hornocker 1983), group size varies. Average mean group size in California estuaries was 1.6 (range 1.0–2.7) otters with maximum group sizes ranging from 1 to 7 animals (Brzeski et al. 2013) whereas otters in marine coastal Scotland tend to be solitary (Kruuk and Moorhouse 1991). Substantial variation is observed for North American river otters in Alaska, with reports of groups containing 5–18 individuals (Testa et al. 1994) and a mean minimum group size of 1 or 2 otters (Blundell et al. 2002). In Iowa, where habitat is similar to Illinois, adult and yearling river otter males are typically solitary as, also, are females (Melquist and Hornocker 1983). Females may be found in social family groups consisting of the female and her offspring, although occasionally a family group may be accompanied by an unrelated individual (Melquist and Hornocker 1983). In Illinois, visits by solitary animals occurred more often than visits by groups of animals. River otters spent more time in the latrine when visiting as a group. By using camera traps we were unable to reliably discern river otter age, so we cannot discount the possibility that group latrine visits were more likely to include juveniles engaging in social behaviors, such as play. Animals may spend less time in latrines as they age, leading to changing behavior preferences at latrine sites over the life of an individual.

Our finding that most visits were solitary agrees with previous studies in Pennsylvania and Maryland, where 59 % of visits were by single river otters (Stevens and Serfass 2008). However, a study in Idaho reported only 44 % of visits by single otters (Melquist and Hornocker 1983). It has been hypothesized that visits by solitary otters is a method of communicating fine scale resource availability (Kruuk 1992, 2006). Eurasian river otters use spraint to advertise whether they have fished in a particular site. By doing so, the second otter to attempt to use the same site gathers information on whether the area is likely to be depleted (Kruuk 1992, 2006).

Because most visits were by solitary animals, it was not surprising that solitary behaviors were observed more often than group behaviors. For example, self-grooming was observed more often than allogrooming, consistent with reports of free-ranging river otters in Idaho (Melquist and Hornocker 1983). Use of camera traps limited our ability to definitively differentiate between mock or play mating and true copulation. As a result, we combined these behaviors into a single mounting category. Observation frequency of mating behavior was low but consistent with low frequency of copulation observed among Idaho river otters (Melquist and Hornocker 1983). River otters copulate on land and in water (Liers 1951), but given the rarity of observations at the latrine site, if they copulate on land, they use terrestrial locations other than latrines.

Although river otters have a reputation for being playful, play seems less prevalent among free-ranging otters than among captive otters (Melquist and Hornocker 1983). Wrestling has been regarded as play behavior, and even though play behavior typically occurs among juveniles, wrestling play has been observed among adult river otters also (Beckel 1991). Play behavior among Idaho river otters generally consisted of wrestling among juveniles and was only observed 6 % of the time. Although we could not determine age, wrestling comprised 3.4 % of all behavior events (based on frequency) at latrine sites, supporting the idea that free-ranging river otters may play less than captive otters. Furthermore, play is likely to occur throughout a river otter’s range, not exclusively at latrines. It is important to note that solitary animals do not wrestle, and if we limit the observations to social behaviors (i.e., allogroom, wrestle, mount), wrestling comprised 44.4 % of social observations. Wrestling has been observed among captive, wild-caught otters (Hansen et al. 2009); this behavior was specifically described as play by Rostain et al. (2004), given the lack of aggression. Allogrooming, social behavior also observed in latrines, was observed for the same otters (Rostain et al. 2004; Hansen et al. 2009).

Our study revealed seasonal and monthly variation in patterns of visitation rates similar, but not identical, to patterns observed across North America. River otters in Illinois most often visited latrines in the winter, specifically in December and January, more so than any other time of the year. In Idaho, river otters were most active in February with activity becoming progressively less in spring, summer, and fall (Melquist and Hornocker 1983). In Pennsylvania and Maryland, latrine visits peaked in February and March (Stevens and Serfass 2008), slightly later than in our study. Stevens and Serfass (2008) hypothesized a connection between visitation rate and breeding season. Although the exact breeding season of river otters in Stevens and Serfass’ (2008) study range was unknown, the breeding season is known to occur in March and April in Maryland (Mowbray et al. 1979) and New York (Hamilton and Eadie 1964). If the breeding season occurs in March and April, the peak in the visitation rate observed by Stevens and Serfass (2008) occurred just before the breeding season, during the time male river otters would be searching for mates. If visitation rates are a reliable indicator of breeding season, the results of our study are indicative of an earlier breeding season in Illinois than in other locations. Breeding season, specifically time of parturition, is likely to vary depending on geographic location (Harris 1968). However, further research on other latrines and years of observation are needed to determine the robustness of the visiting patterns observed to date.

In general, river otters tend to be more active at night or during crepuscular hours than during the day (Melquist and Hornocker 1983). Our data support this, with a distinct pattern of nocturnal activity in the latrines although the duration of visits was the same whether the animal visited the latrine at night or during the day. Several factors can affect daily activity patterns, including predator and prey activity (Stevens and Serfass 2008). It has also been suggested that humans may pose the biggest threat to river otters and that human presence may force them to be more active at night (Melquist and Hornocker 1983; Stevens and Serfass 2008). Our study site was located on private property where landowners were active, potentially pressuring the local otters to be more active at night.

In conclusion, our behavioral assessment supports the hypothesis that latrines are used for olfactory communication among river otters although the content of the messages is still unknown. The most common behaviors were standing and sniffing, which indicates that river otters gather information about conspecifics via olfactory cues during latrine visits. Although we observed low frequency of defecation events, body rubbing was common. It is possible that the otters use body rubbing to deposit scents at latrines in addition to depositing feces, urine, and anal jelly. However, the lack of defecation events raises concerns about the accuracy of the scat surveys used to assess river otter populations. Although latrines may be used to communicate information between individuals and groups, the fact that latrines were most often visited by solitary otters indicated that social activity at the latrine site is not likely to be a major attraction for river otter visits. We found river otters in Illinois to be more active at latrines at night than during the day, a pattern that might be explained by human activity. We also observed a peak in latrine visitation rate during the winter months of December and January, potentially indicating an earlier breeding season in Illinois. A great deal of information remains unknown regarding river otter latrine function and use. By studying additional latrine sites for additional years we may begin to understand the patterns of behavior of river otters in Illinois and provide the necessary baseline information for testing behavioral hypotheses pertaining to latrine function.

References

Altmann J (1974) Observational study of behavior: sampling methods. Behaviour 49:227–267

Beckel AL (1991) Wrestling play in adult river otters, Lutra canadensis. J Mammal 72:386–390

Begg CM, Begg KS, Du Toit JT, Mills MGL (2003) Scent-marking behaviour of the honey badger, Mellivora capensis (Mustelidae), in the southern Kalahari. Anim Behav 66:917–929. doi:10.1006/anbe.2003.2223

Ben-David M, Blundell GM, Kern JW et al (2005) Communication in river otters: creation of variable resource sheds for terrestrial communities. Ecology 86:1331–1345

Blundell GM, Ben-David M, Bowyer RT (2002) Sociality in river otters: cooperative foraging or reproductive strategies? Behav Ecol 13:134–141

Bridges AS, Noss AJ (2011) Behavior and activity patterns. In: O’Connell AF, Nichols JD, Karanth KU (eds) Camera Traps Anim Ecol. Methods Anal. Springer, Tokyo, pp 57–69

Brown RE, Macdonald DW (1985) Social odours in mammals. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Brzeski KE, Gunther MS, Black JM (2013) Evaluating river otter demography using noninvasive genetic methods. J Wildl Manage 77:1523–1531. doi:10.1002/jwmg.610

Clapperton BK (1989) Scent-marking behavior of the ferret, Mustela furo L. Anim Behav 38:436–446

Dubuc LJ, Krohn WB, Owen RB (1990) Predicting occurrence of river otters by habitat on Mount Desert Island, Maine. J Wildl Manage 54:594–599

Eisenberg JF, Kleiman DG (1972) Olfactory communication in mammals. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 3:1–32. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.03.110172.000245

Erlinge S, Sandell M, Brinck C (1982) Scent-marking and its territorial significance in stoats, Mustela erminea. Anim Behav 30:811–818

Gorman M, Trowbridge B (1989) The role of odor in the social lives carnivores. In: Gittleman J (ed) Carnivore Behavior, Ecology and Evolution. Chapman & Hall Ltd, New York, pp 57–88

Hamilton WJ, Eadie WR (1964) Reproduction in the otter, Lutra canadensis. J Mammal 45:242–252. doi:10.1126/science.95.2469.427-b

Hansen H, McDonald DB, Groves P et al (2009) Social networks and the formation and maintenance of river otter groups. Ethology 115:384–396. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.2009.01624.x

Harris CJ (1968) Otters: a study of the recent Lutrinae. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London

Hutchings MR, White PCL (2000) Mustelid scent-marking in managed ecosystems: implications for population management. Mamm Rev 30:157–169

Irwin MT, Samonds KE, Raharison J-L, Wright PC (2004) Lemur latrines: observations of latrine behavior in wild primates and possible ecological significance. J Mamm 85:420–427

Kruuk H (1992) Scent marking by otters (Lutra lutra): signaling the use of resources. Behav Ecol 3:133–140

Kruuk H (2006) Otters: ecology, behavior and conservation. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Kruuk H (2014) Sprainting into the wind. IUCN/SCC Otter Spec Gr Bull 31:12–14

Kruuk H, Moorhouse A (1991) The spatial organization of otters (Lutra lutra) in Shetland. J Zool 224:41–57

Liers EE (1951) Notes on the river otter (Lutra canadensis). J Mamm 32:1–9. doi:10.1126/science.95.2469.427-b

Mason CF, Macdonald SM (1987) The use of spraints for surveying otter Lutra lutra populations: an evaluation. Biol Conserv 41:167–177. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(87)90100-5

Melquist WE, Hornocker MG (1983) Ecology of river otters in west central Idaho. Wildl Monogr 83:3–60

Mowbray EE, Pursley D, Chapman JA (1979) The status, population characteristics and harvest of the river otter in Maryland. Publ. Wildl. Ecol. No. 2. Maryl. Wildl. Adm. Maryl. Dep. Nat. Resour. Annapolis, MD

Newman DG, Griffin CR (1994) Wetland use by river otters in Massachusetts. J Wildl Manage 58:18–23

Oldham AR, Black JM (2009) Experimental tests of latrine use and communication by river otters. Northw Nat 90:207–211. doi:10.1898/NWN08-20.1

Rasa AE (1973) Marking behaviour and its social significance in the African dwarf mongoose, Helogale undulata rufula. Z Tierpsychol 32:293–318

Roper TJ, Conradt L, Butler J et al (1993) Territorial marking with faeces in badgers (Meles meles): a comparison of boundary and hinterland latrine use. Behaviour 127:289–307

Rostain RR, Ben-David M, Groves P, Randall JA (2004) Why do river otters scent-mark? An experimental test of several hypotheses. Anim Behav 68:703–711. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.10.027

Stafford R, Goodenough AE, Slater K et al (2012) Inferential and visual analysis of ethogram data using multivariate techniques. Anim Behav 83:563–569. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2011.11.020

Stevens SS, Serfass TL (2008) Visitation patterns and behavior of nearctic river otters (Lontra canadensis) at latrines. Northeast Nat 15:1–12

Swimley TJ, Serfass TL, Brooks RP, Tzilkowski WM (1998) Predicting river otter latrine sites in Pennsylvania. Wildife Soc Bull 26:836–845

Testa JW, Holleman DF, Bowyer RT, Faro JB (1994) Estimating populations of marine river otters in Prince William Sound, Alaska, using radiotracer implants. J Mamm 75:1021–1032

Van Zyll de Jong CG (1987) A phylogenetic study of the Lutrinae (Carnivora; Mustelidae) using morphological data. Can J Zool 65:2536–2544. doi:10.1139/z87-383

Wendland WM (1994) Paleoclimates—A guide to climates of the future. In: McIsaac G, Edwards WR (eds) Sustainable agriculture in the American Midwest. University of Illinois Press, Champaign, pp 215–230

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the private landowners at Riverbend Association for agreeing to participate in the study. The authors also thank Samantha K Carpenter for assistance with data collection and Jennifer Mui who prepared example videos and still photographs of river otter behavior. This research was supported by the Illinois Natural History Survey at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, the James Scholar Program in the College of ACES at the University of Illinois, the University of Illinois Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research, and the I-STEM Education Initiative through the University of Illinois.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material 1 (MP4 3223 kb). Allogroom behavior; licking or scratching with forepaws or hind-paws another river otter’s fur

Supplementary material 2 (MP4 1762 kb). Self-groom behavior; licking own body, licking paws and rubbing paws on face, scratching fur with forepaws or hind-paws

Supplementary material 3 (MP4 1442 kb). Wrestle behavior; one or more river otters jumping on another river otter; jumping may result in one otter pinning another otter to the ground

Supplementary material 4 (M4 V 2401 kb). Mount behavior; one river otter mounting another, biting of nape of neck may occur during mounting

Supplementary material 5 (MP4 1525 kb). Stand behavior; river otter is stationary, no walking or running movement

Supplementary material 6 (MP4 1553 kb). Sniff behavior; nose of the river otter is to the ground, head movement back and forth, either while the animal is stationary or walking; nose to other river otters

Supplementary material 7 (MP4 1837 kb). Feed behavior; river otter eating or chewing on fish, mussels, crawfish, etc.

Supplementary material 8 (MP4 3512 kb). Body rub behavior; river otter rubbing head and neck on ground, or dragging ventral portion of body on ground

Supplementary material 9 (M4 V 4667 kb). Stomp behavior; hind feet alternately lifted up and down

Supplementary material 10 (M4 V 1132 kb). Defecate behavior; river otter eliminating fecal matter

Supplementary material 11 (MP4 1510 kb). Dig behavior; river otter using front legs to move dirt, leaves, etc., on ground

Supplementary material 12 (MP4 808 kb). Travel head down behavior; river otter walking or running with head down, pointed at ground

Supplementary material 13 (MP4 655 kb). Travel head up behavior; river otter walking or running with head up, parallel to or not pointed at ground

Supplementary material 14 (MP4 1199 kb). Partial view behavior; only part of the river otter body is visible (i.e., tail, head, leg)

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Green, M.L., Monick, K., Manjerovic, M.B. et al. Communication stations: cameras reveal river otter (Lontra canadensis) behavior and activity patterns at latrines. J Ethol 33, 225–234 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10164-015-0435-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10164-015-0435-7