Abstract

We report the case of a 70-year-old female patient with granulomatous interstitial nephritis (GIN) induced by carbamazepine (CBZ). The patient had a 22-year history of bipolar disorder. Approximately 50 days before admission to our hospital, she was switched from valproic acid to 200 mg/day CBZ for mood swings. Forty days later, she presented with mild transient platelet depletion and liver dysfunction along with a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 2.65 mg/dL. At that time, she discontinued CBZ without consulting the doctor. She subsequently developed high fever and a pruritic maculopapular rash. Laboratory tests revealed an elevated CRP level (11.98 mg/dL) and serum creatinine (sCr) of 1.6 mg/dL. Hence, she was admitted to our hospital, where she showed eosinophilia and immunoglobulin suppression. She was diagnosed with atypical drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS). All drugs prescribed by the previous doctor were discontinued. A lymphocyte transformation test showed CBZ positivity; a renal biopsy revealed many granulomatous lesions connected to arterioles, without angionecrotic findings. The patient had no history of allergic disorders or tuberculosis. Because of psychological instability, we treated her conservatively without steroid administration. She had a good recovery except for mild residual renal insufficiency (sCr, 1.0 mg/dL). Although granuloma formation has been observed in kidney biopsy specimens of rare cases with DIHS, no previous studies have reported on the relationship between arterioles and granuloma formation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Drug-related rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) or drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS) is a life-threatening multiorgan systemic reaction characterized by rash, fever, lymphadenopathy, hepatitis, and leukocytosis with eosinophilia [1]. These conditions are caused by a limited number of drugs, including carbamazepine, phenytoin, phenobarbital, zonisamide, allopurinol, dapsone, salazosulfapyridine, and mexiletine [2].

Renal dysfunction associated with DIHS/DRESS has been reported to occur in 10% of cases and is attributable to acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) [2, 3]. In rare cases with DIHS, granuloma formation has also been described, i.e., granulomatous interstitial nephritis (GIN) [4–6].

Here we describe the case of a patient with bipolar disorder and biopsy-proven GIN that developed during the course of carbamazepine-induced DIHS/DRESS.

Case report

A 70-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital because of high fever and acute kidney injury. She had been visiting a psychiatric clinic for bipolar disorder since the age of 48 years and another medical clinic for mild hypertension since the age of 63 years. She had no history of allergic disorders or tuberculosis.

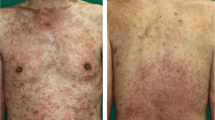

Approximately 50 days before admission, she was switched from valproic acid to 200 mg/day carbamazepine (CBZ) for mood swings. Approximately 40 days after initiation of CBZ, she presented with purpura on the legs. She visited her regular physician. Laboratory analyses revealed platelets of 10.6 × 104/μL, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 62 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) of 107 IU/L, C-reactive protein (CRP) of 2.65 mg/dL, and serum creatinine (sCr) of 0.76 mg/dL. Tranexamic acid (750 mg/day) and levofloxacin (LVFX, 300 mg/day) were prescribed. At that time, she discontinued CBZ without consulting her doctor. Three days later, she developed fever of >38°C, although the purpura had disappeared. She visited our hospital, where laboratory results showed an increased platelet count (12.8 × 104/μL), slightly deteriorating liver dysfunction (AST, 70 IU/L; ALT, 123 IU/L), and an elevated CRP level (4.7 mg/dL). We suspected some viral infection as the cause of her symptoms and bed rest was prescribed. Four days after the onset of fever, a pruritic maculopapular rash appeared on the trunk and extremities. Because of the prolonged high fever and an elevated CRP level (7.13 mg/dL), she was referred to our hospital again. Laboratory tests revealed deteriorating renal function (sCr, 1.6 mg/dL) without urinalysis abnormalities and a further elevated CRP level (11.98 mg/dL), although liver function improved (AST, 14 IU/L; ALT, 41 IU/L). She was hospitalized the next day.

On admission, her blood pressure was 130/70 mmHg, pulse rate was 68 beats/min, and body temperature was 38.2°C. A diffuse skin rash was present on the trunk and limbs. The chest, heart, and abdominal findings were unremarkable. No superficial lymphadenopathies or swelling of the joints were observed.

Laboratory data on admission revealed eosinophilia and immunoglobulin (Ig) suppression with no evidence of paraproteinemia (Table 1). Complement levels were normal. Renal ultrasonography revealed symmetrical and unobstructed kidneys with normal cortical echotexture. Computed tomography findings of chest and abdominal were unremarkable. No ophthalmological complications were observed.

As systemic drug allergy was suspected, all drugs prescribed by the previous doctor were discontinued. The lymphocyte transformation test showed CBZ positivity and LVFX negativity;CBZ was therefore considered to be the causative drug. Reactivation of human herpes virus (HHV)-6 and HHV-7 was not detected. The patient was diagnosed with DRESS and atypical DIHS because she fulfilled all three criteria for DRESS diagnosis and five of the seven criteria for DIHS diagnosis, which were as follows: maculopapular rash developing approximately 6 weeks after initiation of CBZ, prolonged clinical symptoms 2 weeks after discontinuation of CBZ, fever >38°C, renal dysfunction, and eosinophilia [2, 11].

Following hospitalization, she often experienced insomnia and nocturnal delirium. Psychiatric consultation disclosed a hypomanic state. Because her physical symptoms had not worsened, we decided to treat her conservatively without steroids.

The general condition of the patient improved with conservative therapy (Fig. 1). Approximately 10 days after admission, her temperature returned to normal and the skin rash disappeared. Approximately 10 days later, eosinophilia improved and CRP levels normalized.

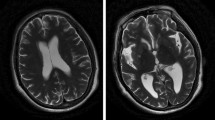

A renal biopsy was performed 11 days after admission (Figs. 2, 3). Eight glomeruli were evident; one was sclerosed and the remaining were almost normal. The interstitium showed patchy infiltration of inflammatory cells and non-caseating granulomas with multinucleated giant cells connected to some arterioles. The findings of an immunofluorescent study were non-specific. The patient was diagnosed with acute GIN.

One month after admission, the sCr level decreased to 1.0 mg/dL and Ig levels returned to normal.

Although olanzapine and lorazepam were administered to control the hypomanic state, they were poorly tolerated because of episodes of akathisia. Eventually, administration of Yokukansan, which is a traditional Chinese herb, resulted in a reasonably stabilized mood without side effects.

The patient was discharged and remained in a stable condition throughout follow-up.

Discussion

GIN is a relatively rare histological diagnosis, comprising only a small proportion of all renal biopsies [7–10]. Common causes of GIN are drugs, sarcoidosis, infections, and Wegener’s granulomatosis; drugs account for 25–45% of GIN cases [7–10]. Medications associated with GIN include anticonvulsants, antibiotics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, allopurinol, and diuretics [7–10]. Although the pathological mechanism underlying GIN is not completely understood, a T-cell-mediated reaction is likely responsible because of the predominance of mononuclear cells (mainly T cells) in the interstitial infiltrates, the presence of granulomas, and the absence of Ig deposition in the tubules or interstitium [7].

DRESS is a life-threatening multiorgan systemic reaction accompanied by the stepwise development of fever, skin rash, leukocytosis with eosinophilia, and liver or renal dysfunction [11]. DIHS is an almost identical disease concept, although an association with HHV-6 reactivation and a prolonged course are emphasized in DIHS [1]. The criteria for DIHS diagnosis include a maculopapular rash developing >3 weeks after initiation of therapy with a limited number of drugs, prolonged clinical symptoms 2 weeks after discontinuation of the causative drug, fever >38°C, liver abnormalities (ALT, >100 IU/L), leukocyte abnormalities including leukocytosis (>11000/μL), atypical lymphocytosis (>5%) or eosinophilia (>1500/μL), lymphadenopathy, and HHV-6 reactivation [2]. Diagnosis of definite or typical DIHS requires the presence of all seven criteria. Probable or atypical DIHS is diagnosed in patients fulfilling the first five criteria in whom HHV-6 reactivation cannot be detected. Renal dysfunction can serve as a substitute for liver abnormalities. Recent studies have demonstrated that other herpes viruses, such as cytomegalovirus, Epstein–Barr virus, and HHV-7, can be sequentially reactivated during the course of this syndrome [12].

The clinical features of DIHS/DRESS, distinguished from other types of drug reactions, include paradoxical deterioration after withdrawal of the causative drugs and frequent flare-ups as observed in immune reconstitution syndrome (IRS) [1, 13]. A limited number of drugs such as anticonvulsants have been reported to cause DIHS/DRESS [1]. Typically, a decrease in serum Ig levels, including IgG, IgA, and IgM, is observed at the onset of DIHS/DRESS [1]. An increase in Ig levels is observed several weeks after withdrawal of the causative drugs, and the levels finally return to normal. This transient hypogammaglobulinemia is likely attributable to a pharmacologically mediated immunomodulatory effect on the immune system by the causative drugs [1, 14–16].

Superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltration, predominantly consisting of T cells, and tissue eosinophilia are common pathological findings of skin biopsy [1, 17]. Although only a small number of reports are available on histological analyses of the other involved organs, renal failure in some cases with DIHS/DRESS has been attributed to AIN [2]. In rare cases with DIHS, granuloma formation has also been observed and reported as GIN or granulomatous necrotizing angiitis [4–6]. Our patient showed granulomatous lesions connected to arterioles, without findings of apparent angionecrosis. There have been no previous reports of GIN similar to the present case, and the significance of this finding is unclear.

Granulomas can be found in other organs, such as the skin, liver, and colon, in association with DIHS/DRESS [4–6, 18]. Furthermore, granuloma formation is a histological hallmark of IRS [13]. Some researchers propose that DIHS/DRESS is a manifestation of the newly observed IRS [13]. Further investigations into the pathogenesis of these syndromes are expected.

Systemic corticosteroid therapy is recommended for treating patients with DIHS/DRESS who do not show improvement even after withdrawal of the causative drug [1]. The usual dosage is 40–60 mg/day prednisolone, which should be carefully tapered to prevent flare-ups. Mild cases that recover with only supportive care do not require corticosteroids [1, 4]. The use of systemic corticosteroids may increase the risk of infectious complications including virus reactivation. Other treatment options include intravenous IgG [1, 14]. Even after resolution of clinical manifestations, a number of drugs should be avoided because unexplained cross-reactivities to multiple drugs with structures totally different from the original causative drugs have been reported [1].

Fortunately, our case recovered with conservative therapy. We believed that we might have difficulty in achieving a good psychiatric control if systemic corticosteroids were required. Only a limited number of options were available for psychiatric management of the patient because of intolerance to various psychotropic drugs and a possible cross-reactivity to multiple drugs after developing DIHS/DRESS.

HHV-6 and HHV-7 reactivation was not detected in our case. These viruses have been demonstrated to be involved in the flare-up and severity of this syndrome; therefore, the absence of a detectable HHV-6 and HHV-7 reactivation may have accounted for the milder form of disease in our case [19, 20].

In summary, we report a case of GIN associated with CBZ-induced DIHS/DRESS. Supportive care after drug discontinuation resulted in a good recovery. Early recognition of this syndrome is the most important step in treatment because a number of drugs such as anticonvulsants and antibiotics may worsen the clinical symptoms due to unexplained cross-reactivities.

References

Shiohara T, Inaoka M, Kano Y. Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS): a reaction induced by a complex interplay among herpesviruses and antiviral and antidrug immune responses. Allergol Int. 2006;55:1–8.

Kano Y, Shiohara T. The variable clinical picture of drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome/drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms in relation to the eliciting drug. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2009;29:481–501.

Revuz J. New advances in severe adverse drug reactions. Dermatol Clin. 2001;19:697–709.

Imai H, Nakamoto Y, Hirokawa M, Akihama T, Miura AB. Carbamazepine-induced granulomatous necrotizing angiitis with acute renal failure. Nephron. 1989;51:405–8.

Hegarty J, Picton M, Agarwal G, Pramanik A, Kalra PA. Carbamazepine-induced acute granulomatous interstitial nephritis. Clin Nephrol. 2002;57:310–3.

Fervenza FC, Kanakiriya S, Kunau RT, Gibney R, Lager DJ. Acute granulomatous interstitial nephritis and colitis in anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome associated with lamotrigine treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36:1034–40.

Mignon F, Méry JP, Mougenot B, Ronco P, Roland J, Morel-Maroger L. Granulomatous interstitial nephritis. Adv Nephrol Necker Hosp. 1984;13:219–45.

Viero RM, Cavallo T. Granulomatous interstitial nephritis. Hum Pathol. 1995;26:1347–53.

Bijol V, Mendez GP, Nosé V, Rennke HG. Granulomatous interstitial nephritis: a clinicopathologic study of 46 cases from a single institution. Int J Surg Pathol. 2006;14:57–63.

Joss N, Morris S, Young B, Geddes C. Granulomatous interstitial nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:222–30.

Bocquet H, Bagot M, Roujeau JC. Drug-induced pseudolymphoma and drug hypersensitivity syndrome (drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: DRESS). Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1996;15:250–7.

Kano Y, Hiraharas K, Sakuma K, Shiohara T. Several herpesviruses can reactivate in a severe drug-induced multiorgan reaction in the same sequential order as in graft-versus-host disease. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:301–6.

Shiohara T, Kurata M, Mizukawa Y, Kano Y. Recognition of immune reconstitution syndrome necessary for better management of patients with severe drug eruptions and those under immunosuppressive therapy. Allergol Int. 2010;59:333–43.

Kano Y, Inaoka M, Shiohara T. Association between anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome and human herpesvirus 6 reactivation and hypogammaglobulinemia. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:183–8.

Moreno-Ancillo A, Cosmes Martín PM, Domínguez-Noche C, Martín-Núñez G, Fernández-Galán MA, López-López R, et al. Carbamazepine induced transient monoclonal gammopathy and immunodeficiency. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2004;32:86–8.

Młodzikowska-Albrecht J, Steinborn B, Zarowski M. Cytokines, epilepsy and epileptic drugs–is there a mutual influence? Pharmacol Rep. 2007;59:129–38.

Ang CC, Wang YS, Yoosuff EL, Tay YK. Retrospective analysis of drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome: a study of 27 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:219–27.

Fernando SL, Henderson CJ, O’Connor KS. Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome with superficial granulomatous dermatitis—a novel finding. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:611–3.

Tohyama M, Hashimoto K, Yasukawa M, Kimura H, Horikawa T, Nakajima K, et al. Association of human herpesvirus 6 reactivation with the flaring and severity of drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:934–40.

Oskay T, Karademir A, Ertürk OI. Association of anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome with Herpesvirus 6, 7. Epilepsy Res. 2006;70:27–40.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Eguchi, E., Shimazu, K., Nishiguchi, K. et al. Granulomatous interstitial nephritis associated with atypical drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome induced by carbamazepine. Clin Exp Nephrol 16, 168–172 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-011-0531-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-011-0531-0