Abstract

The reproductive cycle of Trophon geversianus (Pallas 1774) population from Golfo San José (Chubut, Argentina, 42°33′S, 64°33′W) was studied using histochemical methods and digital image analysis. For such purpose, ovary samples were taken monthly between July 2006 and August 2007 and stained with hematoxylin and eosin, Sudan black B (to identify lipids) or Schiff’s ninhydrin (to identify proteins). Four different gametogenic stages were described: oogonias, previtellogenic oocytes, early vitellogenic oocytes, and late vitellogenic oocytes. Two spawning events were registered; one between September and October 2006, and a second one between February and March 2007. Oocyte quality was determined by the changes in lipid and protein composition during gametogenesis. Through digital image analysis, a lipid and a protein indexes (LI and PI) were calculated. Significant differences were observed in LI over month sampled, contrarily to what PI showed. A significant and positive correlation was found between lipid and protein content and oocytes areas, indicating that these nutrients accumulate during the entire vitellogenesis. Also, when dividing the oocytes into two size groups, analysis indicates a positive correlation between LI and oocyte area for smaller area oocytes. This demonstrates that while proteins accumulate linearly throughout vitellogenesis process, lipids accumulate in two steps: first at a growing rate, secondly at constant rate. This information is essential to determine the nutritional requirements of brood stock individuals at hatcheries in this potential fishery resource that inhabits patagonian waters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Trophon geversianus (Pallas 1774) (Neogastropoda: Muricidae) is a benthonic species which inhabits hard substrates, usually associated with bivalve populations (Pastorino 2005). It is commercially exploited in Chile (González et al. 2007) and in Argentina. It is currently a potential fisheries resource (Cumplido et al. 2010), representing the broadest distribution range of the Trophon genus: from Buenos Aires province to Burdwood Bank in the Atlantic Ocean′s shores and on the Pacific coast from Chiloé Island to Cape Horn (Pastorino 2005; Cumplido et al. 2010). T. geversianus is a dioecious species with internal fertilization and direct embryonic development (Zaixso 1973; Penchaszadeh 1976). Recently, some reproductive aspects as spermatogenesis were studied in the same population of Golfo San Jose (Giménez 2013). In Golfo Nuevo population (Chubut, Argentina), spawning period ranges from May to November and in each event, females lay 12 egg capsules with an average of 197 eggs each one (Cumplido et al. 2010). In laboratory observations, only four eggs per capsule reached the juvenile stage, while the rest of them remained nurse eggs (Cumplido et al. 2011).

Lipids and proteins are largely accepted as invertebrates’ oocyte quality indicators (e.g., Pandian 1969; Gallager and Mann 1986; McEdward and Coulter 1987; Le Pennec et al. 1990; Fukazawa et al. 2005). Rodríguez Jaramillo (2004) used histochemical techniques combined with digital image analysis to quantify changes in oocytes lipid content in the penshell Atrina maura during oogenesis. Furthermore, with this procedure, they have quantified the effect of water temperature and seston concentration on gametogenesis (Rodríguez Jaramillo 2004; Angel-Dapa et al. 2010). The same method was used to quantify lipid and protein content in oocytes of the pearl oyster Pinctada mazatlanica in relation to water temperature and chlorophyll “a” concentration as oocyte quality indicators (Gómez-Robles et al. 2005; Gómez-Robles and Saucedo 2009).

The aim of the present work is to study the oogenesis stages of T. geversianus, to quantify lipid and protein contents of the oocytes by histochemistry and examine its variation throughout oogenesis during a one-year period.

Materials and methods

Specimens of T. geversianus were collected manually from the intertidal rocky shore at Golfo San José (42°33′S, 64°33′W) in Chubut, Argentina, between July 2006 and August 2007. Samples were collected monthly (n ≥ 24) except for the months of August and December 2006, and January, June, and July 2007, when sampling was not possible due to adverse meteorological conditions. The mean water surface temperature was obtained from Red ANTARES (2006) and the photoperiod from Servicio de Hidrografía Naval Argentino (SHN 2007).

Total shell length of every individual was measured with a vernier caliper to the nearest millimeter. After the removal from shell, the individuals were sexed by the presence or absence of a penis and albumen gland. A small piece of female gonads was fixed in a 7 % formalin solution and subsequently stored in a 70 % ethanol solution. Tissues were dehydrated using an ascending series of ethanol concentrations and then embedded in paraplast (Biopack®). Sections were severed at 3 μm with a manual microtome (Leitz®). Thereafter, Sudan black B (SBB) and Schiff’s ninhydrin (NIN) histochemical techniques were used to identify lipid (Bayliss High 1990) and protein elements (Yasuma and Ichikawa 1953), respectively.

In order to topographically characterize the ovary, gonads of some individuals were embedded in resin (Leica Historesin®), cut at 5 μm with an electronic microtome (Leica RM 2155®) and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Gametogenenic stage frequency

Ten female individuals per month were selected to study the relative frequency of germ cells’ developmental stages during oogenesis, and from each ovary, thirty germinal cells were randomly selected and classified.

Oocyte quality indicators during months and oogenesis

Two oocyte quality indicators were estimated: lipid content (L) and lipid index (LI), in SBB sections (n = 4 or 5 per month); and protein content (P) and protein index (PI), in NIN sections (n = 3 or 4 per month). For this purpose, from each section, 20 vitellogenic oocytes were randomly selected, observed under a light microscope (Zeiss®), and photographed with a Canon® digital camera.

The images were archived and processed with AxioVision® 4.8.2 software to measure the areas occupied by the oocyte (O), nucleus (N), lipids, and proteins. The cytoplasm area was calculated as the difference between O and N (Fig. 1a). L was calculated as the area occupied by lipid inclusions (blue pixels) and P as the area occupied by protein inclusions (magenta pixels) each within the cytoplasm area (Fig. 1b). Finally, LI and PI were calculated as:

Transverse section of Trophon geversianus ovary in paraplast sections, stained with Sudan black B. a The area occupied by a vitellogenic oocyte (O) and its nucleus (N) is delimited, resulting in the cytoplasm area (C). b The software identifies every blue pixel within the cytoplasm. The area occupied by lipids (L) is the sum of the blue pixels. Scale bar 50 μm (color figure online)

For each ovary studied, an average LI or PI was calculated; thus, 4–5 independent LI and 3–4 independent PI were obtained per month. The variations in these variables (L, LI, P, and PI) were studied over a one-year period.

The variation in oocyte quality through development was studied over the relationship between the oocyte quality indicators (L, LI, P, and PI) and O; therefore, four analyses were made: L–O, LI–O, P–O, and PI–O. For such purpose, one oocyte per individual was randomly selected for each analysis. Later on, all oocytes were divided into two groups: <10,000 and >10,000 μm2 concerning area sizes, one oocyte of each size group was randomly chosen per individual, and correlation analyses were made between LI and O, and between PI and O in each size group.

Statistical analyses

Changes in LI and PI between months were analyzed by a one-way ANOVA followed by a post hoc Tukey test when needed (Zar 1999). Correlation analysis (Pearson or Spearman’s r) (Zar 1999) between oocyte quality indicators, and O were made. Data normality and variance homogeneity were evaluated with Shapiro-Wilks and Levene tests, respectively. The significance level of all analyses was set a priori at α = 0.05.

Results

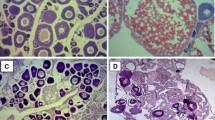

The ovary of T. geversianus is a multi-tubular organ situated in the apical portion of the visceral mass, in close association with the digestive gland and surrounded by a simple columnar epithelium (Fig. 2a). Each tubule is composed by germinal and accessory cells and surrounded by connective tissue. Oogenesis was divided in four developmental stages (Fig. 2):

Transverse sections of Trophon geversianus ovaries in resin sections, stained with hematoxylin and eosin. a General view of the ovary. Arrowhead shows simple columnar epithelium. b Oogonias (Oog) and previtellogenic oocytes (Pvo). c Early vitellogenic oocyte (Evo). d Late vitellogenic oocyte (Lvo). Scale bar a 100 μm; b–d 50 μm

-

Oogonias (Oog): small spherical cells with nucleus occupying almost the entire cell area. They were found frequently forming groups of three or four cells (Fig. 2b).

-

Previtellogenic oocytes (Pvo): the nucleus and cytoplasm increased in volume. No evidence of yolk presence in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2b).

-

Early vitellogenic oocytes (Evo): irregularly shaped cells with small inclusions indicating the onset of yolk synthesis (Fig. 2c).

-

Late vitellogenic oocytes (Lvo): large irregularly shaped cells characterized by the presence of large and rounded yolk inclusions (Fig. 2d).

The four developmental stages were observed in each female studied, and no spatial developmental pattern was observed within the tubules or between them.

Gametogenic stage frequency

All gametogenic stages were found in every month studied (Fig. 3). Intermediate Lvo frequencies were observed during July and September 2006, followed by a decrease in October of the same year, suggesting a partial spawning event between September and October. At the same time, an increase in the mean surface water temperature was observed along with a 13 light-hour photoperiod. During October and November 2006, the lowest Lvo and the highest Oog frequencies were observed, in concordance with an increasing temperatures and light hours. In February 2007, Lvo frequency was high but decreased remarkably during March, suggesting another partial spawning event in the population. Simultaneously, an increase in mean surface water temperature and a 13 light-hour photoperiod was registered. High Lvo frequencies were observed during April 2007, returning to intermediate Lvo frequencies in May and August 2007 (Fig. 3).

Oocyte quality indicators during months and oogenesis

Significant differences were found in LI among months during the sampling period (ANOVA, F (8, 35) = 3.65, P < 0.05). Tukey post hoc analysis revealed that the LI of November 2006 was significantly lower than that of July 2006, March, and April 2007 (Fig. 4a). No significant differences were found in PI between months (ANOVA, F (7, 23) = 2.13, P = 0.08) (Fig. 4b).

Monthly variations in lipid index (LI) and protein index (PI) in oocytes of Trophon geversianus. a LI annual variation (mean ± SE, n = 4–5). Significant differences in LI between months are indicated with different symbols (Asterisks, filled diamonds). b PI annual variation (mean ± SE, n = 3–4). No significant differences were found in PI between months

A significant and positive correlation between L and O (Pearson correlation, r = 0.08, N = 43, P < 0.001) and between P and O (Spearman rank correlation, r s = 0.78, N = 31, P < 0.001), indicates an increase in both yolk types’ content during oogenesis (Fig. 5a, b). No significant correlation was found between LI and O or between PI and O.

Lipid and protein content in Trophon geversianus. a Relationship between lipid content and oocyte area. Significant Pearson correlation was found (r = 0.80; p < 0.001). b Relationship between protein content and oocyte area. Significant nonparametric Spearman correlation was found (r = 0.78; p < 0.001)

In oocytes <10,000 μm2, a significant and positive correlation was observed between LI and O (Pearson correlation, r = 0.33, N = 43, P < 0.05) (Fig. 6a), but there was no correlation between PI and O (Fig. 6b). For oocytes >10,000 μm2, no significant correlation was verified between LI or PI and O (Fig. 6a, b).

Lipid index (LI) and protein index (PI) in oocytes <10,000 and >10,000 μm2 of area in Trophon geversianus. a Relationship between LI and oocyte area (O). Significant Pearson correlation between LI and O was found in oocytes <10,000 μm2 (r = 0.33; p < 0.05) but not in cells >1,000 μm2. b Relationship between PI and O. No significant correlation was found in oocytes <10,000 μm2 nor in oocytes <10,000 μm2

Discussion

Germinal cells in different developmental stages were observed every month in T. geversianus females, indicating the absence of a resting phase in the gametogenic cycle of Golfo San José’s population. Between September and October 2006, and between February and March 2007, the frequency of Lvo decreases markedly, suggesting spawning events in the population. These events, in turn, coincided with rises in the mean surface water temperature and a 13 light-hour photoperiod, agreeing with Cumplido et al. (2010), who observed that T. geversianus females maintained in laboratory conditions began spawning when the photoperiod reached 13 light hours. It has also been reported by histological methods that spawning events in other template water marine gastropods are induced by changes in water temperature (Giménez and Penchaszadeh 2002; Arrighetti and Penchaszadeh 2010).

Late vitellogenic oocytes frequencies remained relatively high from February to September, indicating the existence of not synchronized spawning events in the population during this period, coinciding with Cumplido et al. (2010), who observed mating events in Punta Cuevas (Golfo Nuevo, Chubut) from late March to late October and spawning events from May to November.

Variations in LI and Lvo frequency followed the same trend along the studied period except for February and March 2007. In February, despite the high Lvo frequency, LI was low; thus, it is possible that oocytes have a lower quality than those observed during autumn and winter. In March, LI increases, indicating that Lvo remaining after the first spawning event in the year have a better quality than those previously evacuated. The positive relationship observed between lipid and protein content and the area of oocytes indicate that yolk is accumulated along the entire cell development. Despite no relationship was found between LI and O or between PI and O, it was possible to verify a positive trend among the smaller area oocytes, so it was decided to separate the oocytes into two groups, <10,000 and >10,000 μm2 of area. This classification was based on Knack Almeida et al. results (personal communication) who have determined oocytes >10,000 μm2 as mature. The positive relationship found between LI and O among oocytes <10,000 μm2 suggests that during early stages of vitellogenesis the rate at which lipids are accumulated increases to remain constant in larger oocytes. This means that at the onset of vitellogenesis, the proportion of each oocyte occupied by lipids increases, but when cells reach certain size, the relationship between these two variables remains constant until the oocyte is spawned, although they keep on growing in size and in lipid content. In contrast, the proportion of oocyte occupied by proteins remains constant throughout the entire vitellogenesis. Furthermore, the proportion of the oocyte occupied by proteins, in general, was lower than lipids.

The similarities observed between gametogenic stages frequency and monthly LI, along with the fact that LI is higher than PI in every month studied and along the entire vitellogenenic process, suggests that the amount of lipid yolk is more important than the amount of proteinaceous yolk as a nutritive source for T. geversianus embryos and that LI is a good indicator of oocyte quality and reproductive cycle dynamics.

The use of lipids as the main energy source during larval development was registered in several mollusk species, e.g., Haliotis discus hannai (Fukazawa et al. 2005), Mercenaria mercenaria, and Crassostrea virginica (Gallager and Mann 1986), while protein function has been more discussed as an embryonic reserve. In other mollusks species with extra-embryonic nutritive sources, proteinaceous yolk does not necessarily have a nutritive function (Elbers and Bluemink 1960; Jong Brink et al. 1983). In general, lipid and protein content of oocytes is measured with conventional biochemical methods (e.g., Barnes and Blackstock 1973 in Chaparro et al. 2006 for lipids or Bradford 1976). Nonetheless, such methods overestimate lipid and protein reserves in oocytes as it considers structural elements as well. Besides, due to the need to separate tissues precisely, it might result inaccurate to study organisms whose gonad is diffuse or macroscopically undistinguishable from other organs, such as the ovary of T. geversianus.

Yolk is crucial to embryos and larvae survival in mollusks (e.g., Pandian 1969; Gallager and Mann 1986; Le Pennec et al. 1990; Vavra and Manahan 1999; Fukazawa et al. 2005; Chaparro et al. 2006). Currently, induced spawning of several mollusks species has been achieved during culture through manipulation of certain variables such as photoperiod, temperature, and diet (Uki and Kikuchi 1984; Devauchelle and Mingant 1991). It is important to study oocytes quality in terms of these variables in order to understand the conditions in which more resistant larvae could be obtained.

Yolk present in T. geversianus fertilized eggs has a double nutritional function for embryos. Zaixso (1973) observed that T. geversianus consumes part of its own yolk during the earlier embryonic stages, and when the stomodeum appears, the larvae start feeding mainly on nurse eggs (Penchaszadeh 1976; Cumplido et al. 2011). These nurse eggs are known to be the main nutritive source for embryos in other gastropod species with intracapsular development (Gallardo 1979; Martínez et al. 2008). Indeed, the highest organic material concentration in Chorus giganteus embryos is found after the nurse eggs are consumed (Martínez et al. 2008); in Nucella crassilabrum, significant differences in size are observed among embryos coming from the same capsule due to the different amount of nurse eggs consumed by each individual (Gallardo 1979). Similarly, in T. geversianus laboratory spawns, the highest embryonic growing rate is registered during nurse egg consumption (Cumplido et al. 2011). According to Cumplido (2008), nurse eggs do not differ from viable ones more than by its genetic charge, thereby it is probable that the main nutritional component of nurse eggs is yolk.

Based on our findings, it is possible to conclude that oocytes incorporated more lipid reserves during March to April in 2007 and during June in 2006. LI is a useful and reliable indicator of gamete development and quality in T. geversianus since PI temporal changes during oogenesis were not relevant.

References

Angel-Dapa MA, Rodríguez-Jaramillo C, Cáceres-Martínez CJ, Saucedo PE (2010) Changes in lipid content of oocytes of the Penshell Atrina maura as a criterion of gamete development and quality: a study of histochemistry and digital image analysis. J Shellfish Res 29:407–413. doi:10.2983/035.029.0217

Arrighetti F, Penchaszadeh PE (2010) Gametogenesis, seasonal reproduction and imposex of Adelomelon beckii (Neogastropoda: Volutidae) in Mar del Plata, Argentina. Aquat Biol 9:63–75. doi:10.3354/ab00226

Barnes H, Blackstock J (1973) Estimation of lipids in marine animals and tissues: detailed investigation of the sulphophosphovanillin method for “total” lipids. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 12:103–118. doi:10.1016/0022-0981(73)90040-3

Bayliss High OB (1990) Lipids. In: Bancroft JD, Stevens A (eds) The theory and practice of histological techniques, 3rd edn. Churchill Livingstone, New York, pp 215–244

Bradford MM (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72:248–254. doi:10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3

Chaparro OR, Navarrete LR, Thompson RJ (2006) The physiology of the larva of the Chilean oyster Ostrea chilensis and the utilization of biochemical energy reserves during development: an extreme case of the brooding habit. J Sea Res 55:292–300. doi:10.1016/j.seares.2005.11.003

Cumplido M (2008) Estacionalidad reproductiva y desarrollo embrionario del caracol Trophon geversianus en el intermareal de Punta Cuevas, Golfo Nuevo. Seminario de licenciatura, Universidad Nacional de la Patagonia San Juan Bosco, Golfo Nuevo

Cumplido M, Averbuj A, Bigatti G (2010) Reproductive seasonality and oviposition induction in Trophon geversianus (Gastropoda: Muricidae) from Golfo Nuevo, Argentina. J Shellfish Res 29:423–428. doi:10.2983/035.029.0219

Cumplido M, Pappalardo P, Fernández M et al (2011) Embryonic development, feeding and intracapsular oxygen availability in Trophon geversianus (Gastropoda: Muricidae). J Molluscan Stud 77:429–436. doi:10.1093/mollus/eyr025

Devauchelle N, Mingant C (1991) Review of the reproductive physiology of the scallop, Pecten maximus, applicable to intensive aquaculture. Aquat Living Resour 4:41–51

Elbers PF, Bluemink JG (1960) Pinocytosis in the developing egg of Limnaea stagnalis L. Exp Cell Res 21:619–622

Fukazawa H, Takami H, Kawamura T, Watanabe Y (2005) The effect of egg quality on larval period and postlarval survival of an abalone Haliotis discus hannai. J Shellfish Res 24:1141–1147

Gallager SM, Mann R (1986) Growth and survival of larvae of Mercenaria mercenaria (L.) and Crassostrea virginica (Gmelin) relative to broodstock conditioning and lipid content of eggs. Aquaculture 56:105–121. doi:10.1016/0044-8486(86)90021-9

Gallardo CS (1979) Developmental pattern and adaptations for reproduction in Nucella crassilabrum and other muricacean gastropods. Biol Bull 157:453–463

Giménez J (2013) Spermatogenesis and sperm morphology in Trophon geversianus (Gastropoda: Muricidae). J Mar Biol Assoc UK 93:1881–1886. doi:10.1017/S0025315413000581

Giménez J, Penchaszadeh PE (2002) Reproductive cycle of Zidona dufresnei (Caenogastropoda: Volutidae) from the southwestern Atlantic Ocean. Mar Biol 140:755–761. doi:10.1007/s00227-001-0748-7

Gómez-Robles E, Saucedo PE (2009) Evaluation of quality indices of the gonad and somatic tissues involved in reproduction of the pearl oyster Pinctada mazatlanica with histochemistry and digital image analysis. J Shellfish Res 28:329–335. doi:10.2983/035.028.0215

Gómez-Robles E, Rodríguez-Jaramillo C, Saucedo PE (2005) Digital image analysis of lipid and protein histochemical markers for measuring oocyte development and quality in pearl oyster Pinctada mazatlanica (Hanley, 1856). J Shellfish Res 24:1197–1202

González J, Daza E, Guzmán C, et al (2007) Diagnóstico para la administración y conservación del recurso caracol Trophon en Bahía Gente Grande, XII Región. p 186

Jong Brink M, Boer HH, Joosse J (1983) Mollusca. In: Adiyodi KG, Adiyodi RG (eds) Reproductive biology of invertebrates: oogenesis, oviposition and oosorption. Willey, New York, pp 297–355

Le Pennec M, Gueguen F, Cochard JC, Paulet YM, Dorange G (1990) Relations entre le contenu lipidique des ovocytes de Pecten maximus (Mollusque, Bivalve) et les performances des larves en elevage. Haliotis 10:101–113

Martínez G, López V, Mettifogo L, Cancino JM (2008) Energy source utilization by embryos and larvae of the muricid snail Chorus giganteus (Lesson, 1829). J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 354:65–80. doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2007.10.014

McEdward LR, Coulter LK (1987) Egg volume and energetic content are not correlated among sibling offspring of starfish: implications for life-history theory. Evolution 41:914–917

Pallas PS (1774) Spicilegia Zoologica quibus novaeimprimis et obscurae animalium species iconibus, descriptionibus atque commentariis illustrantur. Berolini 1(10):41–44

Pandian TJ (1969) Yolk utilization in the gastropod Crepidula fornicata. Mar Biol 3:117–121. doi:10.1007/BF00353430

Pastorino G (2005) A revision of the genus Trophon Montfort, 1810 (Gastropoda: Muricidae) from southern South America. Nautilus 119:55–82

Penchaszadeh PE (1976) Reproducción de gastrópodos prosobranquios del Atlántico Suroccidental. El género Trophon. Physis 35:69–76

Red ANTARES (2006) Península de Valdés (Estación EGI). In: Red ANTARES. http://www.antares.ws

Rodríguez Jaramillo C (2004) Efecto de la temperatura sobre la gametogénesis en el callo de hacha Atrina maura (Sowerby, 1835) (Bivalvia: Pinnidae). Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Maestría

SHN (2007) Salida y puesta del sol. Comodoro Rivadavia. In: Servicio de Hidrología Naval. http://www.hidro.gov.ar/

Uki N, Kikuchi S (1984) Regulation of maturation and spawning of an abalone, Haliotis (Gastropoda) by external environmental factors. Aquaculture 39:247–261. doi:10.1016/0044-8486(84)90270-9

Vavra J, Manahan DT (1999) Protein metabolism in lecithotrophic larvae (Gastropoda: Haliotis rufescens). Biol Bull 196:177–186

Yasuma A, Ichikawa T (1953) Ninhydrin-Schiff and alloxan-Schiff staining; a new histochemical staining method for protein. J Lab Clin Med 41:296–299

Zaixso HE (1973) Observaciones sobre el desove y embriología de Trophon geversianus (Pallas, 1774) (Gastropoda Muricidae). Neotropica 19:156–162

Zar JH (1999) Biostatistical analysis. Prentice Hall, New Jersey

Acknowledgments

JG and FA are members of the research career of CONICET, and PB and HKA are doctoral fellow of CONICET. We are grateful to N. Burroni for her assistance and valuable comments. This work was partially funded by PIP 0253 and UBACyT X273.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by H.-D. Franke.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de la Barra, P., Giménez, J., Knack de Almeida, H. et al. Vitellogenesis and changes in lipid and protein content of oocytes of Trophon geversianus (Neogastropoda: Muricidae) in Golfo San José (Chubut, Argentina). Helgol Mar Res 68, 179–185 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10152-014-0380-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10152-014-0380-9