Abstract

Early macrobenthos succession in small, disturbed patches on subtidal soft bottoms is facilitated by the arrival of post-larval colonizers, in particular by active and passive dispersers along the seafloor or through the water column. Using a field experiment at two contrasting sites (protected vs. exposed to wave action), we evaluated the role of (a) active and passive dispersal through the water column and (b) the influence of small-scale spatial variability during succession of subtidal macrobenthic communities in northern Chile. Containers of two sizes (surface area: small—0.12 m2 and large—0.28 m2) at two positions above the natural substratum (height: low—3 cm and high—26 cm) were filled with defaunated sediment, installed at two sandy sublittoral sites (7–9 m water depth) and sampled after 7, 15, 30, 60 and 90 days, together with the natural bottom sediment. The experiment took place during austral fall (from late March to early July 2010), when both larval and post-larval stages are abundant. At the exposed site, early succession was driven by similar proportions of active and passive dispersers. A sequence from early, late and reference communities was also evident, but container position and size affected the proportional abundance of dispersal types. At the protected site, the successional process started with abundant colonization of active dispersers, but toward the end of the experiment, the proportion of swimmer/crawlers increased, thus resembling the dispersal types found in the natural community. At this site, the position above the sediment affected the proportional abundance of dispersal types, but patch size had no effect. This study highlights that macrobenthic post-larvae can reach at least 26 cm high above the bottom (actively or passively, depending on site exposure), thus playing an important role during early succession of sublittoral soft bottoms. The active or passive use of the sediment–water interphase may also play an important role in the connectivity of benthic populations and in the recovery after large-scale disturbances of sublittoral habitats.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Marine soft-bottom sediments are inhabited by diverse macrofauna, including sedentary and highly mobile species (Lenihan and Micheli 2001). These communities are impacted by several types of disturbances that vary in intensity and magnitude over different spatial scales (Thistle 1981; Hall et al. 1994; Rosenberg 2001; Sousa 2001). The recovery of benthic soft-bottom communities after disturbances involves different mechanisms of colonization depending on the spatial scale of the disturbance (Norkko et al. 2006). For example, in small- and intermediate-sized disturbances, for example patches created by benthic predators, typically ranging from 0.1 to 1 m2 (VanBlaricom 1982; Thrush et al. 1991; Commito et al. 1995; Micheli 1997), recolonization via lateral immigration of adult and post-larval stages from the surrounding undisturbed sediments dominates the initial stages of community succession (Zajac et al. 1998; Thrush et al. 2000). In contrast, in large-scale disturbances, for example those generated by extensive algal mats, >100 m2 (Thiel and Watling 1998) or storm disturbances (Yeo and Risk 1979; see review in Sousa 2001), where lateral immigration may not extend to the center of the disturbed patch, larval settlement of pioneer species may be important to initiate the colonization process (Günther 1992; Whitlatch et al. 1998). In small- and intermediate-sized patches, a combination of lateral immigration, water column recruitment and larval settlement can be expected. Depending on the dynamics of the system, recolonization is expected to proceed very rapidly in small (~0.1 m2) patches where lateral immigration of subadult and adult stages might predominate (Smith and Brumsickle 1989), whereas in slightly larger patches, recruitment via the water column (by larvae or post-larvae) may gain importance (Thrush et al. 1996).

Studies examining the effects of spatial-scale variation (e.g. patch size) have shown that even small-scale variability of soft-bottom communities might affect species composition, colonization modes and recovery rates (Smith and Brumsickle 1989; Ruth et al. 1994; Thrush et al. 1996). In addition, resource (food, oxygen) availability may be influenced by patch size, thereby influencing population dynamics of opportunistic species (Norkko et al. 2006, 2010). However, even though it is recognized that community development depends on the size of disturbed patches, experiments on community succession are often conducted in single size areas using either defaunated plots or trays (e.g. Lu and Wu 2000; Dernie et al. 2003; Zajac and Whitlatch 2003; Van Colen et al. 2008; Guerra-García and García-Gómez 2006, 2009 and many others).

There is strong evidence of scale-dependent effects on macrobenthic recovery in intertidal sandy and muddy systems (Smith and Brumsickle 1989; Ragnarsson 1995; Thrush et al. 1996; Norkko et al. 2006), but few studies are available for subtidal habitats (Ruth et al. 1994; Norkko et al. 2010). Both types of systems (intertidal and subtidal soft bottoms) may differ in colonization mechanisms and transport processes. In intertidal systems, strong tidal currents and bedload transport occur during high tide, and thus, larval settlement and dispersal of post-larvae and adults is highly dependent on tidal dynamics (e.g. Armonies 1994; Zühlke and Reise 1994). Furthermore, during the low tide period, there is no colonization via the water column but only by lateral movement in the sediment. In subtidal habitats with less intense hydrodynamics, bedload transport has been suggested to be relevant (Valanko et al. 2010), but water column dispersal and diel vertical migrations (i.e. actively emerging benthos) might be an equally or more important mechanism of dispersal and colonization (Alldredge and King 1985; Kaartvedt 1986; Kringel et al. 2003). These differences between inter- and subtidal systems have been noted in colonization experiments using containers filled with defaunated sediments that were placed above the substratum. In intertidal systems, edge effects along the container border may influence the colonization processes by precluding lateral immigration by crawlers and burrowers or by affecting bedload transport and bottom hydrodynamics (Smith and Brumsickle 1989). In contrast, colonization studies using containers in subtidal sedimentary habitats have suggested that isolation above the seafloor has only minor effects on the colonization processes (e.g. Arntz and Rumohr 1982, 1986; Lu and Wu 2000; Guerra-García and García-Gómez 2006, 2009) because the primary mode of post-settlement dispersal of the dominant species is via pelagic dispersal (Levin 1984; Ritter et al. 2005).

Post-larval macrofaunal colonization in experimental devices (e.g. containers or trays with only an upward facing opening) depends on the ability of organisms to rise and disperse above the natural bottom (actively or passively) or their ability to crawl over the container walls. Thus, colonization might be more limited to a few species depending on their elevation capacity (Armonies 1994). In sublittoral habitats in our study location, we have previously observed that succession in containers elevated 5 cm above the bottom filled with defaunated sediment is mainly driven by post-larval immigrants from the surrounding sediment. In fact, after 6 months of exposition, the community in experimental containers reached a composition that was very similar to the natural community (Pacheco et al. 2010). However, the dispersal mechanism during colonization into such devices (i.e. active and/or passive dispersal through the water column, crawling along the natural bottom or a combination of mechanisms) or the height to which soft-bottom macrofauna can rise above the bottom is not well known.

Shallow subtidal soft-bottom communities in northern Chile are subject to small and local, as well as ecosystem-scale disturbances. Extensive disturbances affecting large areas of the ecosystem occur during unusually heavy rainfall that episodically (i.e. every 10–20 years near rivers) deposit huge amounts of flood sediments on the seafloor (Vargas et al. 2000). Small disturbed patches are created by the foraging and burrowing activities of a variety of predatory fish and crabs (Pacheco 2009; Pacheco et al. 2010). This type of disturbance is very frequent, intense and known to generate patches of different sizes (Auster and Crockett 1984; Auster et al. 1991), resulting in patchy communities reflecting different successional recovery stages (e.g. VanBlaricom 1982; Thrush et al. 1991; Commito et al. 1995; Micheli 1997). These small- and intermediate-sized patches may range from 0.005 up to 3.24 m2 (Smith and Brumsickle 1989; Ruth et al. 1994; Ragnarsson 1995; Thrush et al. 1996). It can be expected that small patches (~0.1 m2) are quickly recolonized from the surrounding undisturbed habitats, whereas recovery of larger patches (0.1–1 m2) may take longer and be influenced by water column colonization. Herein, we examined the succession of these small and intermediate-sized patches, using specifically designed experiments that mimic such small spatial-scale variability.

A field colonization experiment was conducted at two sublittoral sites in northern Chile using containers filled with defaunated sediments of two different sizes and positioned 3 and 26 cm above the natural bottom. We hypothesized that (1) early succession in containers elevated higher above the bottom will be driven principally by active dispersal of post-larvae, (2) early succession in containers closer to the bottom will be driven by a combination of active and passive water column/bottom dispersal (e.g. crawlers) and (3) at more advanced successional stages, the contribution of all dispersal types will be similar both in experimental and in natural communities.

Materials and methods

Study sites

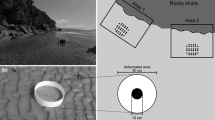

A colonization experiment was conducted from late March to early July 2010 (during austral fall) at two sublittoral sites in northern Chile (Humboldt Current System), near Antofagasta. The region is characterized by strong upwelling, where cold waters with high nutrient and low oxygen contents rise to the surface (Piñones et al. 2007; Pacheco et al. 2011). One site (Colorado: 23°30′S; 70°31′W) is located in the northern part of Antofagasta Bay and the other site (Bolsico: 23°28′S; 70°36′W) in a small cove at the southern part of Península Mejillones (Fig. 1). During the course of the experiment, bottom water temperatures were recorded with a temperature logger (Stowaway Tidbit, 30 min interval records) attached 50 cm above the bottom in the location mooring at each experimental site, over four consecutive days (from 31 March to 3 April in Colorado and from the 28 to 31 March in Bolsico). Current flow above the bottom was measured using an acoustic current meter (Falmouth Scientific 2-Dimensional Acoustic Current Meter, model 2D-ACM). The current meter was placed 50 cm above the bottom and exposed for 4 h (10 am to 14 pm) in early July 2011, during 7 days in Colorado (1–7 July) and during 7 days in Bolsico (8–14 July). Our regular observations of the hydrodynamics at both study sites confirmed that the current data from those days are representative of the general conditions during the experimental period.

Selection of experimental sediments

To select sediments for the experiment, pilot samples were collected from several sandy beaches along the coast of the region. Samples were taken from the upper and driest fringe of the beach, ensuring clean and defaunated sediments. Granulometric parameters were estimated by sieving 100 g of dry sediment through a set of geological sieves (4-, 2-, 1-, 0.5-, 0.25-, 0.125- and 0.063-mm mesh sizes, respectively) that were arranged in a sieve tower and shaken for 10 min. Sediment type was categorized according to the weight of dry sediment (expressed in percentage) retained in each sieve according to the Wentworth scale (Buchanan 1984). Grain size average (φ) and sorting degree were estimated following the methodology described in Folk and Ward (1957). The resulting granulometric parameters from the beaches and in situ experimental sites were compared. Thereafter, sediments were collected from matching beaches after raking the surface and removing large stones or debris (e.g. glass or plastic). Sediments were stored in plastic bags for 2 weeks.

During the experiment, the organic matter content of each type of sediment (experimental and natural) was estimated as percent loss of mass after 4 h burning at 450°C. On each sampling date, three independent sediment samples from each treatment (12 samples in total) plus three samples of the natural sediment were taken with a small core (4.5 cm diameter) that was inserted to a sediment depth of 7 cm. The sediment samples from the experimental containers were taken from the undisturbed sediment remaining in the containers after these had been sampled for macrobenthic organisms (see “Sampling strategy and processing of samples” in the next section). Sediments were dried in an oven at 60°C for 3 days. From each sample, 10 g was used for organic matter content measurements, and another 100 g was used for the estimation of granulometric parameters.

Experimental set-up

This study examined succession at relative small scales (0.12–0.28 m2) herein referred to as small and large treatments. Sets of fifty small (plastic boxes of 26 cm height, 35 × 35 cm side length and 0.12 m2 area) and fifty large containers (plastic cylinders of 26 cm height, 60 cm diameter and 0.28 m2 area) were filled with defaunated sediment and installed at each experimental site. Twenty-five containers of each size were buried in the sediment, only reaching 3 cm above the natural substratum. Another twenty-five containers of each size were placed above the sediment surface. Thus, two heights (3 and 26 cm above the bottom) were assigned, herein referred to as low and high treatments, respectively. Holes slightly larger than the diameter and depth of both containers sizes were carefully dug by SCUBA divers for installing the buried containers. Plastic knots hooked to the rim of each container were used for identification during underwater sampling; thus, none of the experimental units were re-sampled. Containers were deployed in four parallel lines, keeping a distance of ~1.5 m among containers and thereby ensuring sufficient interspersion between experimental units (Quinn and Keough 2002). Once a container was positioned, closed bags with the defaunated sediment were deposited inside. When all experimental units were installed, four SCUBA divers opened and filled the containers simultaneously, trying to avoid disturbance of the surrounding bottom as much as possible. The amount of sediment provided enough mass to anchor the containers on top of the sediment. A previous experiment in these habitats had revealed no seasonal effects in the resulting communities (Pacheco et al. 2010), but in order to fulfill the requirements for the present study (presence of larval and post-larval stages), the experiment was initiated at the end of the austral summer, a season when both larvae and post-larvae are abundant (e.g. Avendaño et al. 2007).

The experiment started on 17 March in Colorado and 20 March in Bolsico. During the experiment, we lost 14 containers (ten small and four large) before the last sampling in Colorado due the occurrence of a strong swell. Shortly after the last sampling day, all remaining containers and other artifacts were carefully retrieved by divers from both study sites in order to keep the environment clean.

Sampling strategy and processing of samples

Containers were sampled 7, 15, 30, 60 and 90 days after the start of the experiment at each locality. At each sampling date, five independent containers from each treatment were randomly sampled using a core (10 cm diameter and 15 cm high) that was inserted centered 10 cm into the sediment in each filled container. The collected sediment was carefully deposited in plastic bags and sealed with a marked rubber ring. At each sampling date, five reference samples from the ambient surrounding sediment were haphazardly taken using the same core. In the field, samples were fixed in a 10% formalin–methanol solution stained with Rose Bengal. Thereafter, in the laboratory, samples were washed and sieved through a 0.5-mm mesh with a 0.3-mm mesh underneath, in order to retain very small organisms.

Macrobenthic organisms were sorted, identified under a stereo-microscope (2–10X, Olympus SZ61) to the lowest taxonomical level possible and counted. Based on knowledge of the biological traits of these taxa, and the preliminary results of an ongoing study that used traps specifically designed to capture post-larvae with particular mechanisms of dispersal three main dispersal groups were assigned: (1) active dispersers that perform diel vertical migrations, (2) swimmers/crawlers and (3) passive dispersers (detailed explanation of the classification criteria is provided in “Appendix A”). For the statistical analyses, the total individual numbers of all species from the three dispersal categories were pooled. Representative subsamples of the most abundant colonizers (determined in rank order of abundance) from all containers and sampling dates were taken and the size of the organisms measured in order to distinguish between juvenile and adult stages (see details of classification in “Appendix B”).

Statistical analysis

To test our hypotheses, we calculated the percentage contribution of each dispersal type to the total abundance of the macrobenthos for each container type and the reference communities. Non-metric multidimensional ordination plots were constructed from the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity matrices using the dispersal type data (total counts per container type) after square root transformation to visualize dissimilarity between dispersal groups within time intervals and experimental containers. To test whether there was a sequential pattern of change over time (i.e. consecutive changes in which dispersal groups from early to late succession become more similar to those in natural reference communities), the seriation analysis implemented in the RELATE routine was conducted for the multivariate data sets from both sites. This test uses the Spearman rank correlation (ρ) between the dissimilarity among samples, and the dissimilarity model matrix that would result from the interpoint distances of the same number of samples equally spaced along a straight line. To evaluate whether the multivariate pattern of change of the dispersal groups is consistent between the two sites, the RELATE routine was used to correlate both Bray–Curtis dissimilarity matrices from both experimental sites.

To test for significant effects of the experimental factors, a three-way permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) was conducted with sampling time (7, 15, 30, 60, 90 days), area size (small and large) and position (low and high) as fixed factors plus the interaction factors for each site. When PERMANOVA detected significant effects for a given factor, pair-wise comparisons were conducted a posteriori using the multivariate version of the t statistic based on Bray–Curtis distances. Statistical analyses were conducted using the new version of PRIMER 6 (Clarke and Gorley 2006) with PERMANOVA β3 software.

Sampling was successfully completed during the experimental time in Bolsico, but a strong oceanic swell swept away all remaining small containers in Colorado 1 week before the last sampling. Therefore, data from the 90-day sampling at this site had to be excluded from the differential statistics in order to avoid statistical problems due to unequal number of replicates.

Results

Both sites are protected areas with relative calm conditions, but Colorado is more exposed to the predominant northward wind, and during days of strong wave action, bottom currents in this location may reach up to 17 cm/s (Table 1). The differences in wave and current exposure are also confirmed by the fact that 14 containers were lost in Colorado while all experimental containers survived until the end of the experiment in Bolsico. At both locations, values of organic matter content in both experimental and natural sediments were below 1%, and granulometric parameters did not vary substantially during the experiment.

In Colorado, there were 33 species present in experimental containers and reference samples. From these species, eight were active dispersers (e.g. diel vertical migrants), 14 were swimmers and/or crawlers, and 12 species depended on passive dispersal through resuspension events (Table 2). In Bolsico, 22 species were recorded from containers and natural sediments. Eight species were active dispersers, seven were swimmers/crawlers, and another seven depended on water column/resuspension dispersal (Table 2).

In Colorado, active (e.g. amphipods Eudevenopus gracilipes, Heterophoxus sp., Aora typica and ostracods) and passive (e.g. bivalves Tagelus dombeii, Nucula pisum) dispersers were the most abundant taxa during the succession process, regardless of the experimental container type (Fig. 2). These proportions were also similar to the natural reference community, although at the end of the experiment, the contribution of swimmers/crawlers increased here (Fig. 2). The nMDS plot suggests that the three analyzed dispersal types followed a progressive change over time, from early via late stages of succession toward the reference community (Fig. 3). This pattern of variation over time was confirmed with the seriation analysis (ρ = 0.34; P < 0.05). However, there is variability in the dissimilarity among container types. PERMANOVA detected significant effects for the three analyzed factors (Table 3), and pair-wise comparisons from the interaction time x size indicated significant differences between small and large containers after 15 (t = 1.123; P < 0.05) and 30 (t = 2.346; P < 0.05) days of exposure.

Non-metric multidimensional scaling ordination plots from both study sites calculated from Bray–Curtis similarity/dissimilarity distance matrix with square root-transformed data of the dispersal group type (i.e. averages for each container type). Numbers indicate the number of days passed since the experiment started

In Bolsico, succession in the containers started with abundant colonization of active dispersers (e.g. amphipods Eudevenopus gracilipes, Ampelisca sp., Aora typica, ostracods and the cumacean Diastylis planifrons) with a minor proportion of swimmers/crawlers (principally the abundant gastropod Nassarius gayi) (Table 2). The contribution of active dispersers remained important during the three first sampling dates of the experiment, regardless of container type (Fig. 2). However, after 60 and 90 days, the contribution of swimmers/crawlers and passive dispersers increased, thus resembling the proportional abundance of dispersal types observed in the reference communities (Fig. 2). A proportion of ~50% active dispersers, ~20% swimmers/crawlers and ~30% passive dispersers were always recorded in natural sediments. In agreement with these results, the nMDS plot shows a progressive change from the beginning of the experiment to the end, with the later dispersal groups being similar to reference samples (Fig. 3). This variation in dissimilarity over time was confirmed with the seriation analysis (ρ = 0.45; P < 0.05) in a similar way to that observed in Colorado. In fact, the RELATE analysis showed a significant correlation (ρ = 0.29; P < 0.05) between both dissimilarity matrices from both sites. In Bolsico, as in Colorado, the variation in dissimilarity between dispersal groups was also associated with the container type (Fig. 3). PERMANOVA detected significant effects for the factors time and position (Table 3). Pair-wise comparisons did not detect significant differences between 15 and 30 days of exposure (t = 1.438; P > 0.05).

Overall, many juvenile and adult organisms colonized the experimental containers (Fig. 4). In Colorado, the proportion of juveniles of the most abundant colonizing species was high compared to reference samples, while in Bolsico, the proportion of juveniles/adults among the active dispersers (Eudevenopus gracilipes, Diastylis planifrons and ostracods) was similar to that found in the reference sediments (Fig. 4). At both sites, a common pattern is evident for passive dispersers (e.g. Tagelus dombeii) and swimmers/crawlers (e.g. Capitella sp.), with only juveniles reaching the experimental sediments (Fig. 4).

Percentage of juveniles and adults recorded from subsamples from experimental (Exp, all container type and all sampling dates pooled) and reference (Ref) sediments. Active dispersers (Eudevenopus gracilipes, Diastylis planifrons, Cylindroleberidae 1), swimmers/crawlers (Branchiostoma elongatum, Capitella sp.) and passive dispersers (Tagelus dombeii)

Discussion

The importance of colonization via the water column during succession in subtidal sediments

At both study sites, the contribution of taxa that actively use the water column for dispersal and colonization was important during the colonization process. Several macrobenthic organisms were fully capable of colonizing sediments 3 cm and 26 cm above the natural sediment. Amphipods Eudevenopus gracilipes, Heterophoxus sp., cumaceans Diastylis planifrons and ostracods perform diel vertical migrations into the water column and colonized all experimental sediments. In other subtidal areas, similar taxa (e.g. amphipods, cumaceans, ostracods) have been reported to migrate vertically high above the bottom as a strategy for food searching, mating, molting or predator avoidance (Alldredge and King 1985; Kaartvedt 1986; Kringel et al. 2003).

Besides the biologically adaptive value of diel vertical migration, we show that this behavior facilitates colonization of disturbed sediment patches. The successional pathway may be strongly modulated by this type of dispersal. In a previous study, we found that succession in containers elevated 5 cm above the sediment follows the tolerance succession model (Pacheco et al. 2010). In this type of succession, species interactions are rather weak, thus allowing early and late colonizers to coexist (Connell and Slatyer 1977). As diel vertical migrants share their time between sediment and water column, this may alleviate negative interactions (e.g. predation, competition), thereby facilitating coexistence during early colonization.

In Colorado, the contribution of passive dispersers was important during succession in containers. Bivalves such as Tagelus dombeii and Nucula pisum colonized all container types in abundant numbers during the experiment. Elsewhere, particularly in intertidal habitats, soft-bottom bivalves and gastropods have been reported to take advantage of bottom hydrodynamics for passive dispersal through the water column (e.g. Armonies 1994; Norkko et al. 2001). Even though our experimental containers were not completely flush with the sediment surface (thus possibly affecting passive bedload transport of organisms, e.g. Snelgrove 1993; Valanko et al. 2010), our results suggest that resuspension events in Colorado may help to transport organisms higher above the bottom for colonization.

In intertidal habitats, the placement of experimental artifacts (e.g. cores and trays) affects the hydrodynamics and thus the arrival modes of post-larval colonizers with passive dispersal (Smith and Brumsickle 1989). Our results suggest that the placement of the container above the sediment may affect the abundance of passive dispersers, but active dispersal was of equal or greater importance during early succession at both study sites. Herein, we used two containers shapes (cylinder and square), and thus, edge effects may have influenced water flow around the respective container type in different ways. Samples were, however, always taken from the center of the containers. Consequently, if edge effects occurred, they can be considered minor. Furthermore, the effects of container size, which could be related to the shape of the container, were not significant in Bolsico.

Several colonization studies emphasized the role of water column dispersal in larval transport and settlement (Guerra-García et al. 2003; Ritter et al. 2005; Lu and Wu 2007). Here, we show that water column dispersal is important but mainly for post-larval and adult colonization. Juveniles and adults of small-sized taxa (e.g. ostracods, amphipods and cumaceans; Fig. 4) were thriving in experimental containers. In the case of Tagelus dombeii, polychaetes of the family Nephtyidae, Cirratulidae, Branchiostoma elongatum and Paraprionospio pinnata, mostly juveniles were found in containers, and large adults were found in the natural sediment. Large and deep-burrowing infauna have been reported to be poor container colonizers, especially when adult specimens are too large to be resuspended and thus cannot reach the containers above the sediment surface (Guerra-García and García-Gómez 2006, 2009). Large species with swimming and burrowing abilities (e.g. large stomatopods, scallops) may colonize all experimental containers, but we did not detect this type of organisms during our experiment, even though they occur in the surrounding reference communities.

The results of the present experiment highlight the importance of post-larval and adult colonization during early stages of the succession. However, another study of succession over a longer period (i.e. 24 months; Pacheco et al. 2010) suggested that larval settlement occurs (e.g. during seasonal changes) and becomes relevant during more advanced stages of succession. Recruitment of some invertebrates in containers occurred after 6 months of succession (Pacheco et al. 2010), but based on our experimental methods, it is difficult to pinpoint the role of larval settlement during early colonization of disturbed sublittoral sediments. As demonstrated here, dispersal and colonization of post-larvae continues throughout succession, and competitive interactions during re-entry into the sediment may gain importance during later stages of succession.

Effects of patch size on macrobenthic succession and convergence to natural communities

The distribution pattern and the abundance of macrobenthic organisms in sedimentary habitats are characterized by a high degree of patchiness due to patchy larval settlement and parent population distribution and also by the variation in patch size generated by the different types of disturbance (Thrush 1991; Ellis et al. 2000). Some conceptual models of succession and recovery of benthic communities emphasize the spatial-scale effects on the abundance of pioneer colonizers (Whitlatch et al. 1998; Zajac et al. 1998). For example, the abundance of pioneer colonizers should increase with increments of patch size, as larger areas will contain fewer predators or competitively superior species that typically appear during late stages of succession (e.g. Norkko et al. 2006). Ruth et al. (1994) reported increments in the number of taxa with increasing surface area of experimental containers (i.e. 0.005, 0.014, 0.04 and 0.102 m2) but no differences in the total abundances of the main colonizers in containers of intermediate sizes. Thrush et al. (1996) and Norkko et al. (2010) found that the abundance of colonizers were area-size dependent, but the whole recovery process is strongly linked to the environmental conditions operating in the specific habitat (i.e. gradient in bottom hydrodynamics and the presence of biogenic structures). Regardless of the position above the natural sediment, we only found an effect of container size in Colorado where large containers were colonized by higher proportions of swimmers/crawlers compared to small containers. The size of the area to be colonized alone is not the only relevant factor during succession. Regarding dispersal types, we found that succession occurs through gradual changes from early to late communities, and proportions of dispersal types in the latter were very similar to the natural community. Our results suggest that the opportunistic response often reported in succession and recovery studies (e.g. Rosenberg et al. 2002; Norkko et al. 2006) is also related to the degree of wave and current exposure of the habitat. While in Colorado early colonizers were active and passive dispersers, in Bolsico active water column dispersers were the most abundant colonizers.

Conclusion and outlook

This study confirms that macrobenthic post-larvae can reach at least 26 cm distance above the bottom (actively or passively, depending on site exposure), thereby playing an important role during early succession of sublittoral soft-bottom communities. While passive dispersal is often reported as the principal mechanism of post-larval transport, our results suggest that many benthic invertebrates also disperse actively during diel vertical migrations. These species reached more than 26 cm above the bottom during colonization, and it remains to be investigated whether these species can swim higher up into the water column (e.g. Alldredge and King 1985; Boeckner et al. 2009). These migrations may also have implications in the bentho-pelagic coupling in terms of energy and organic matter transfer. Our results confirm that initial recovery of small-scale disturbances proceeds rapidly and is facilitated by active dispersal of post-larvae, especially in areas with stronger currents. At present, it is not known whether post-larval colonizers (passive or active dispersal) also contribute to the recolonization after large-scale disturbances (e.g. hypoxic events, sediment deposition after extensive rainfalls). This type of disturbance is less frequent compared to small-scale disturbances, but its impacts are very intense. Future large-scale studies are needed to enhance our understanding of the recovery and succession of sublittoral soft bottoms in the Southeast Pacific.

References

Alldredge AL, King JM (1985) The distance demersal zooplankton migrate above the benthos: implications for predation. Mar Biol 84:253–260

Armonies W (1992) Migratory rhythms of drifting juvenile molluscs in tidal waters of the Wadden Sea. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 83:197–206

Armonies W (1994) Drifting meio-macrofauna invertebrates on tidal flats in Königshafen: a review. Helgoländer Meeresunters 48:299–320

Arntz WE, Rumohr H (1982) An experimental study of macrobenthic colonization and succession, and the importance of seasonal variations in temperate latitudes. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 64:17–45

Arntz WE, Rumohr H (1986) Fluctuations of benthic macrofauna during succession and in an established community. Meeresforschungen 31:97–114

Auster PJ, Crockett LR (1984) Foraging tactics of several crustacean species for infaunal prey. J Shellfish Res 4:139–143

Auster PJ, Malatesta RJ, LaRosa SC, Cooper RA, Stewart LL (1991) Microhabitat utilization by the megafaunal assemblage at a low relief outer continental shelf site—middle Atlantic Bight, USA. J Northwest Atl Fish Sci 11:59–69

Avendaño M, Cantillánez M, Thouzeau G, Peña JB (2007) Artificial collection and early growth of spat of the scallop Argopecten purpuratus (Lamarck, 1819), in La Rinconada Marine Reserve, Antofagasta, Chile. Sci Mar 71:197–205

Boeckner MJ, Sharma J, Proctor HC (2009) Revisiting the meiofauna paradox: dispersal and colonization of nematodes and other meiofaunal organisms in low- and high-energy environments. Hydrobiologia 624:91–106

Buchanan JB (1984) Sediments analysis. In: Methods for the study of marine benthos, IBP, Hand Book 16, Black Well SCI, Pub 158 pp

Clarke KR, Gorley RN (2006) PRIMER v6: user manual/tutorial, Plymouth, PRIMER-E

Commito JA, Currier CA, Kane LR, Reinsel KA, Ulm KA (1995) Dispersal dynamics of the bivalve Gemma gemma in a patchy environment. Ecol Monogr 65:1–20

Connell JH, Slatyer RO (1977) Mechanisms of succession in natural communities and their role in community stability and organization. Am Nat 111:1119–1144

Dernie KM, Kaiser MJ, Richardson EA, Warwick RM (2003) Recovery of soft sediment communities and habitats following physical disturbance. J Exp Mar Bio Ecol 285(286):415–434

Ellis J, Norkko A, Thrush SF (2000) Broad-scale disturbance of intertidal and shallow sublittoral soft-sediment habitats; effects on the benthic macrofauna. J Aquat Ecosyst Stress Recovery 7:57–74

Folk R, Ward W (1957) Brazos River bar, a study in the significance of grain-size parameters. J Sediment Petrol 27:3–27

Guerra-García JM, García-Gómez JC (2006) Recolonization after of defaunated sediments: fine versus gross sand and dredging versus experimental trays. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 68:328–342

Guerra-García JM, García-Gómez JC (2009) Recolonization of macrofauna in unpolluted sands placed in a polluted yachting harbor: a field approach using experimental trays. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 81:49–58

Guerra-García JM, Corzo J, García-Gómez JC (2003) Short-term benthic recolonization after dredging in the harbour of Ceuta, North Africa. PSZNI Mar Ecol 24:217–229

Günther CP (1992) Dispersal of intertidal invertebrates: a strategy to react to disturbances of different scales? Neth J Sea Res 30:45–56

Hall SJ, Raffaelli D, Thrush SF (1994) Patchiness and disturbance in shallow water benthic assemblages. In: Hidrew PS, Giller PS, Raffaelli D (eds) Aquatic ecology; scale, pattern, and processes. Blackwell Scientific, Oxford, England

Jensen (1985) The presence of the bivalve Cerastoderma edule affects migration, survival and reproduction of the amphipod Corophium volutator. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 25:269–277

Kaartvedt S (1986) Diel activity patterns in deep-living cumaceans and amphipods. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 30:243–249

Kringel K, Jumars PA, Holliday DV (2003) A shallow scattering layer: high-resolution acoustic analysis of nocturnal vertical migration from the seabed. Limnol Oceanogr 48:1223–1234

Lenihan HS, Micheli F (2001) Soft sediment communities. In: Bertness MD, Gaines SD, Hay ME (eds) Marine community ecology. Sinauer Associates Inc, Sunderland, Massachusetts, pp 253–287

Levin L (1984) Life history and dispersal patterns in a dense infaunal polychaete assemblage: community structure and response to disturbance. Ecology 65:1185–1200

Lu L, Wu RSS (2000) An experimental study on recolonization and succession of marine macrobenthos in defaunated sediment. Mar Biol 136:291–302

Lu L, Wu RSS (2007) Seasonal effects on recolonization of macrobenthos in defaunated sediment: a series of field experiments. J Exp Mar Bio Ecol 351:199–210

Mees M, Jones MB (1997) The hyperbenthos. Oceano Mar Biol Annu Rev 35:221–255

Micheli F (1997) Effects of predator foraging behavior on patterns of prey mortality in marine soft bottoms. Ecol Monogr 67:203–224

Norkko A, Cummings VJ, Thrush SF, Hewitt JE, Hume T (2001) Local dispersal of juvenile bivalves: implications for sandflat ecology. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 212:131–144

Norkko A, Rosenberg R, Thrush SF, Whitlatch RB (2006) Scale- and intensity-dependent disturbance determines the magnitude of opportunistic response. J Exp Mar Bio Ecol 330:195–207

Norkko J, Norkko A, Thrush SF, Valanko S, Suurkuukka H (2010) Conditional responses to increase scales of disturbance, and potential implications for threshold dynamics in soft-sediment communities. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 413:253–266

Pacheco AS (2009) Community succession and seasonal onset of colonization in sublittoral hard and soft bottoms off northern Chile. PhD thesis, Universität Bremen

Pacheco AS, Laudien J, Thiel M, Oliva M, Arntz W (2010) Succession and seasonal variation in the development of subtidal macrobenthic soft-bottom communities off northern Chile. J Sea Res 64:180–189

Pacheco AS, Gonzales MT, Bremner J, Laudien J, Oliva M, Heilmayer O, Riascos JM (2011) Functional diversity of marine macrobenthic communities from sublittoral soft-bottom habitats off northern Chile. Helgoland Mar Res 65:413–424

Piñones A, Castilla JC, Guiñez R, Largier JL (2007) Nearshore surface temperatures in Antofagasta Bay (Chile) and adjacent upwelling centers. Cienc Mar 33:37–48

Quinn G, Keough M (2002) Experimental design and data analysis for biologists. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Ragnarsson SA (1995) Recolonization of intertidal sediments: the effects of patch size. In: Eleftheriou A, Smith C, Ansell A (eds) Biology and ecology of shallow coastal waters. Olsen & Olsen, Fredensborg, pp 253–260

Ritter C, Montagna PA, Applebaum S (2005) Short-term succession dynamics of macrobenthos in a salinity-stressed estuary. J Exp Mar Bio Ecol 323:57–69

Rosenberg R (2001) Marine benthic faunal successional stages and related sedimentary activity. Sci Mar 65(Suppl 2):107–119

Rosenberg R, Agrenius S, Hellman B, Nilsson HC, Norling C (2002) Recovery of marine benthic habitats and fauna in a Swedish fjord following improved oxygen conditions. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 234:43–53

Ruth BF, Flemer DA, Bundrick CM (1994) Recolonization of estuarine sediments by macroinvertebrates: does microcosm size matter? Estuaries 17:606–613

Smith CR, Brumsickle SJ (1989) The effect of patch size and substrate isolation on colonization modes and rate in an intertidal sediment. Limnol Oceanogr 34:1263–1277

Snelgrove PVR (1993) Hydrodynamic enhancement of invertebrate larval settlement in microdepositional environments: colonization tray experiments in a muddy habitat. J Exp Mar Bio Ecol 176:149–166

Sousa WP (2001) Natural disturbance and the dynamics of marine benthic communities. In: Bertness MD, Gaines SD, Hay ME (eds) Marine community ecology. Sinauer Associates Inc., Sunderland, Massachusetts, pp 85–130

Thiel M, Watling L (1998) Effects of green algal mats on infaunal colonization of a New England mud flat - long-lasting but highly localized effects. Hydrobiologia 375(376):177–189

Thistle D (1981) Natural physical disturbances and communities of marine soft bottoms. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 6:223–228

Thrush SF (1991) Spatial patterns in soft-bottom communities. Trends Ecol Evol 6:75–79

Thrush SF, Pridmore RD, Hewitt JE, Cummings VJ (1991) Impact of ray feeding disturbances on sandflat macrobenthos: Do communities dominated by polychaetes or shellfish respond differently? Mar Ecol Prog Ser 69:245–252

Thrush SF, Whitlatch RB, Pridmore RD, Hewitt JE, Cummings VJ, Wilkinson MR (1996) Scale-dependence recolonization: the role of sediment stability in a dynamic sandflat habitat. Ecology 77:2472–2487

Thrush SF, Hewitt JE, Cummings VJ, Green MO, Wilkinson MR (2000) The generality of field experiments: interactions between local and broad-scale processes. Ecology 81:399–415

Urban HJ (1996) Population dynamics of the bivalves Venus antiqua, Tagelus dombeii, and Ensis macha from Chile at 36°S. J Shellfish Res 15:719–727

Valanko S, Norkko A, Norkko J (2010) Strategies of post-larval dispersal in non-tidal soft-sediment communities. J Exp Mar Bio Ecol 384:51–60

Van Colen C, Montserrat F, Vincx M, Herman PMJ, Ysebaert T, Degraer S (2008) Macrobenthic recovery from hypoxia in an estuarine tidal mud flat. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 372:31–42

VanBlaricom GR (1982) Experimental analyses of structural regulation in a marine sand community exposed to oceanic swell. Ecol Monogr 52:283–305

Vargas G, Ortlieb L, Rutllant J (2000) Historic mudflows in Antofagasta, Chile, and their relationship to the El Niño/Southern oscillation events. Rev Geol Chile 27:155–174

Vergara M, Oliva ME, Riascos JM (2011) Population dynamics of the amphioxus Branchiostoma elongatum from northern Chile. J Mar Biol Assoc UK doi:10.1017/S0025315411000804

Whitlatch RB, Lohrer AM, Thrush SF, Pridmore RD, Hewitt JE, Cummings VJ, Zajac RN (1998) Scale-dependent benthic recolonization dynamics: life stage-based dispersal demographic consequences. Hydrobiologia 375(376):217–226

Yeo RK, Risk MJ (1979) Intertidal catastrophes: effect of storms and hurricanes on intertidal benthos of the Minas Basin, Bay of Fundy. J Fish Res Board Can 36:667–669

Zajac RN, Whitlatch RB (2003) Community and population-level of responses to disturbance in a sandflat community. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 294:101–125

Zajac RN, Whitlatch RB, Thrush SF (1998) Recolonization and succession in soft-sediment infaunal communities: the spatial scale of controlling factors. Hydrobiologia 375(376):227–240

Zühlke R, Reise K (1994) Response of macrofauna to drifting tidal sediments. Helgoländer Meeresunters 48:277–289

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the help of S. Montencino, C. Valdes, A. Valenzuela, P. Bolados, R. Uribe, L. Muñoz, G. Benavides, R. Saavedra and A. Silva during field and laboratory work. R. Guiñez is thanked for the statistical advice. C. Auld kindly revised the English of this manuscript. Will Ambrose Jr. and three anonymous reviewers provided helpful comments on an early draft of this manuscript. This research was funded by the FONDECYT post-doctoral grant No. 3100085 to A.S.P.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Heinz-Dieter Franke.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pacheco, A.S., Thiel, M., Oliva, M.E. et al. Effects of patch size and position above the substratum during early succession of subtidal soft-bottom communities. Helgol Mar Res 66, 523–536 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10152-011-0288-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10152-011-0288-6