Abstract

Background

Diabetes mellitus has been commonly associated with poor surgical outcomes. The aim of this meta-analysis was to assess the impact of diabetes on postoperative complications following colorectal surgery.

Methods

Medline, Embase and China National Knowledge Infrastructure electronic databases were reviewed from inception until May 9th 2020. Meta-analysis of proportions and comparative meta-analysis were conducted. Studies that involved patients with diabetes mellitus having colorectal surgery, with the inclusion of patients without a history of diabetes as a control, were selected. The outcomes measured were postoperative complications.

Results

Fifty-five studies with a total of 666,886 patients comprising 93,173 patients with diabetes and 573,713 patients without diabetes were included. Anastomotic leak (OR 2.407; 95% CI 1.837–3.155; p < 0.001), surgical site infections (OR 1.979; 95% CI 1.636–2.394; p < 0.001), urinary complications (OR 1.687; 95% CI 1.210–2.353; p = 0.002), and hospital readmissions (OR 1.406; 95% CI 1.349–1.466; p < 0.001) were found to be significantly higher amongst patients with diabetes following colorectal surgery. The incidence of septicemia, intra-abdominal infections, mechanical failure of wound healing comprising wound dehiscence and disruption, pulmonary complications, reoperation, and 30-day mortality were not significantly increased.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis and systematic review found a higher incidence of postoperative complications including anastomotic leaks and a higher re-admission rate. Risk profiling for diabetes prior to surgery and perioperative optimization for patients with diabetes is critical to improve surgical outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Twenty percent of surgical patients have diabetes mellitus [1]. As global diabetic prevalence is projected to increase from 9.3% in 2019 to 10.2% by 2030 [2], diabetes continues to be a significant comorbidity that needs to be accounted for during surgical planning. Furthermore, undiagnosed diabetes or ‘pre-diabetes’ results in an underestimation of the true number of patients with diabetes having colorectal surgery, with studies reporting that the true prevalence of diabetes in hospitalised patients has been understated by up to 40% [3, 4]. In the existing literature, poor glycemic control and hyperglycemia has been associated with impaired wound healing and increased susceptibility to infections, leading to an elevated risk of postoperative complications [5]. Furthermore, hyperglycemia results in impairment of the inflammatory mediated response, leading to the failure of local vasodilation, bacteria opsonisation, neutrophil adherence, chemotaxis and phagocytosis. These effects result in decreased peripheral blood flow and angiogenesis which ultimately delay wound healing [6,7,8,9]. Such immunological and physiological changes negatively affect anastomoses and increases the occurrence of infectious complications, leading to poorer surgical outcomes.

Currently, evidence from both multicenter and cohort studies suggest that patients with diabetes having colorectal surgery experience a significantly higher risk of surgical site infection (SSI) [10,11,12] and anastomotic leakage (AL) [13, 14] postoperatively. However, studies exploring the impact of diabetes on other postoperative complications aside from SSI and AL are scarce. As a result, the effect of diabetes on postoperative outcomes, including pulmonary, urinary, and cardiac complications, following colorectal surgery requires further analysis so as to better evaluate the clinical impact of diabetes on surgical outcomes.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

This systematic review and meta-analysis utilize the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines methodology [15]. Relevant articles were identified by conducting a complete search on three electronic databases including Medline, Embase and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) from inception through May 9th 2020. Search terms composed of MeSH terms and keywords relating to “Diabetes” or “Hyperglycemia”, and “Colorectal Surgery” were used. The detailed search strategy used for Medline is presented in Supplementary Material 1. All appropriate abstracts were imported into EndNote X9 to have duplicates removed. Similar methods were employed as with our previous reviews [16, 17].

Criteria for the selection of studies

Articles written in English and Chinese were included in this review paper. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they fulfilled the following criteria: (1) involvement of patients having colorectal surgery for malignant or benign causes; (2) analysis of the association between diabetes and postoperative complications after colorectal surgery; and (3) inclusion of patients without diabetes as control subjects. Studies were excluded if they: (1) were review articles, conference abstracts, non-human cohort studies or case reports; (2) did not involve control subjects; or (3) did not analyse data regarding postoperative complications.

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies including cohort, case–control, or cross-sectional studies were considered for this review. Patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes were included in our analysis, while those with gestational diabetes were excluded. The primary outcome measured was the postoperative complications after colorectal surgery. Short-term complications were defined as complications occurring within 30 days after the surgery was performed, and consisted of AL, septicaemia, SSI, intra-abdominal abscess, acute renal failure, mechanical wounds, cardiac, urinary, and pulmonary complications, ileus, clostridium difficile colitis, and 30-day mortality. Long-term complications were defined as complications occurring more than 30 days after the surgery was performed and consisted of 1-year mortality, reoperation and hospital readmission.

Data extraction and assessment of quality

Predefined data were extracted from the selected articles into a structured proforma by two independent authors, (DT and HTM). Data extracted from each paper included the general information of the study (author’s name, article title, publication year, geographical region of the study, study design and indication for surgery), characteristics of the participants with and without diabetes, and statistical results of postoperative complications. For quality assessment of the included studies, the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Form for Cohort Studies [18] and Jadad Scale [19] were utilized. The Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Form for Cohort Studies [18] is designed to assess the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses and evaluates studies on three domains: the selection of the study groups; the comparability of the groups; and the outcome of interest for cohort studies. The Jadad scale [19] for RCTs is created to assess the methodological quality of a clinical trial, by assessing the effectiveness of blinding.

Statistical analysis

All analysis was conducted in STATA 16.1 (StataCorp LLC). A meta-analysis of proportions was conducted using the metaprop function and effect sizes were pooled in random effects [20]. For the meta-analysis of dichotomous variables, odds ratio (OR) estimates with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were combined and weighted to calculate a pooled OR using the DerSimonian–Laird random-effects method [21]. Significance was considered when p < 0.05. Regardless of inter-study heterogeneity assessed using Cochran Q statistics and I2 statistics, random effects were applied in the analysis of all dichotomous data.

Results

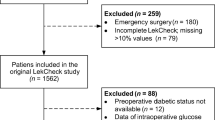

Of the 1734 records identified through the combined search results with duplicates removed, 258 manuscripts were reviewed in full text, and 55 articles [10, 12, 13, 22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56, 58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73] met our inclusion and exclusion criteria (Fig. 1). These included studies consisted of 51 retrospective cohort studies, three prospective cohort studies and one randomized controlled trial. A total of 666,886 patients were included for analysis, comprising 93,173 patients with diabetes and 573,713 patients without diabetes as a control. A summary of the key characteristics and quality assessment of included studies is presented in Supplementary Material 2.

Prevalence of postoperative complications

The prevalence rates of the postoperative complications that were reported in the included studies are summarized in Table 1. Among patients with diabetes, the prevalence rates of SSI after colorectal surgery was 20% (CI 0.16–0.24). The prevalence of intra-abdominal abscess was 6% (CI 0.04–0.09). Septicemia had a prevalence of 6% (CI 0.05–0.06), while mechanical wound complications comprising of wound dehiscence and disruption occurred in 2% (CI 0.01–0.02). Additionally, pooled proportions found a prevalence rate of 8% for urinary complications (CI 0.05–0.11) and pulmonary complications were reported at 5% (CI: 0.03–0.07). AL occurred at a rate of 11% (CI 0.08–0.13) in patients with diabetes (Fig. 2). Thirty-day mortality was 5% (CI 0.00–0.14), hospital readmission 13% (CI 0.12–0.13) and reoperation rate was 6% (CI 0.06–0.07).

Complications in patients with diabetes vs without diabetes

A summary of key outcomes comparing postoperative complications between patients with and without diabetes is presented in Table 1.

Anastomotic leak

In a pooled analysis of 66,457 patients (7936 with diabetes and 58,521 without), it was found that patients with diabetes experienced a significantly higher risk of developing AL (OR 2.40; 95% CI 1.84–3.16, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3).

Infectious complications

From the pooled analysis of 564,889 patients (83,785 with diabetes), patients with diabetes experienced a significantly enhanced risk of SSI (OR = 1.98; 95% CI 1.64–2.39, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4). These complications were of varying severity, with analysis revealing a non-significant difference in rates of intra-abdominal abscess formation (OR = 1.88; 95% CI 0.99–3.57; p = 0.053) in 171,414 patients (24,469 with diabetes). Pooled analysis involving 170,334 patients (24,293 with diabetes) showed that patients with diabetes experienced an increased risk of developing septicaemia postoperatively, although without statistical significance (OR = 2.93; 95% CI 0.35–24.27, p = 0.320).

Systemic postoperative complications

Analysis of 391,776 patients (58,033 with diabetes) indicated a significant difference (OR = 1.69; 95% CI 1.21–2.35, p = 0.002) in the urinary complication rates between patients with and without diabetes. Pooled analysis of 388,878 patients (57,876 with diabetes) showed a non-significant difference in pulmonary complications between patients with and without diabetes (OR = 1.29; 95% CI 0.77–2.16; p = 0.335).

Readmissions and reoperations

In a pooled analysis of 181,867 patients (24,396 with diabetes), diabetes significantly increased the likelihood of hospital readmission following colorectal surgery (OR 1.41; 95% CI 1.35–1.47, p < 0.001). Analysis of 171,050 patients (24,396 with diabetes) yielded non-significant influence (OR = 1.18; CI = 0.99–1.41, p = 0.068) on the rate of reoperation within 30 days of surgery.

30-Day mortality

In a pooled analysis of 31,118 patients (3526 with diabetes), diabetes contributed to an increase in the risk of 30-day mortality (OR 2.65; 95% CI 0.80–8.70, p = 0.109). However, the results were not statistically significant.

Discussion

Diabetes is a well-known risk factor for a range of postoperative complications following colorectal surgery, with its effects on postoperative mortality [74], AL [14], and SSI [75] being well-established. In line with existing literature, this meta-analysis found AL and SSI to be the most commonly reported postoperative complications amongst patients with diabetes. Additionally, several lesser-known complications affecting the respiratory, urinary, and gastrointestinal systems were also identified. Results from this analysis identified diabetes as a significant risk factor for AL and SSI after colorectal surgery. While previous studies [14, 75] have also found significant associations between diabetes and AL and SSI, this study expanded on the existing literature by conducting an analysis of proportions and providing prevalence rates for these complications.

Pooled analysis also found that diabetes increased the occurrence of pulmonary complications following colorectal surgery. Despite this being without overall statistical significance, individual studies reported significant associations between diabetes and pulmonary complications, especially for infectious complications such as pneumonia. Cologne et al. [32] and Ramsey et al. [64] concluded that diabetes was a significant risk factor for pneumonia following surgery for colonic diverticulitis and colectomy. However, this was offset by a large cohort study by Anand et al. [73] which concluded that diabetes was not significantly associated with pulmonary complications after colorectal surgery. While there is a paucity of previous literature reviewing the effects of diabetes on pulmonary complications after colorectal surgery, it has been shown that patients with diabetes are predisposed to lower respiratory tract infections including pneumonia [76] due to compromised immune function. The occurrence of postoperative pneumonia is of considerable clinical interest as it is significantly associated with prolonged length of hospital stay ranging from 7–9 days, as well as increased treatment costs [43, 77]. Further investigation is, therefore, required to strengthen the association between diabetes and pulmonary complications after colorectal surgery.

Furthermore, pooled analysis identified diabetes as a significant risk factor for urinary complications including urinary retention, urinary dysfunction, and urinary tract infection. In particular, Toyonaga et al. [43] found diabetes to be significantly associated with urinary retention after anorectal surgery for benign causes, attributing it to the impairment of autonomic nerves supplying the detrusor muscles within the bladder. Toritani et al. [78] also suggested that diabetes was a risk factor for urinary dysfunction following surgery for rectal cancer due to autonomic nerve impairment which decreases bladder sensation and results in an increased bladder capacity. The significant association between diabetes and postoperative urinary complications has several clinical implications. Given that the prevalence of diabetic bladder dysfunction is already often underestimated in postoperative patients [79], there is a need for closer monitoring of patients with diabetes to prevent re-catheterisation and to allow for earlier detection of urine retention. Akin to patients who have had pelvic surgery with rates of urinary retention of 15–25% [80], patients with underlying diabetic urinary dysfunction may benefit from preoperative bladder training [81] and regular monitoring for urine retention after trial without catheter to mitigate the increased rate of urinary complications associated with diabetes. Preoperative urodynamic factors such as peak flow rate, detrusor straining pressure during voiding, and the presence of straining to the void have also been suggested to be predictive of postoperative urinary retention [82, 83] and could be helpful during surgical planning to manage the occurrence of such complications, especially in high risk groups such as patients with diabetes.

In addition to results from our meta-analysis, several studies included in our review reported less common postoperative complications associated with diabetes. Cologne et al. [32] concluded that diabetes was a significant risk factor for acute renal failure postoperatively after multivariate analysis adjusting for age, sex, and other existing comorbidities (adjusted OR 3.40, 95% CI 2.00–5.60, p < 0.001). This was attributed to the pro-inflammatory effects of diabetes and the resultant micro- and macrovascular pathologies that negatively affect the renal system [84, 85]. The study also emphasized the elevated HbA1c levels in the study population (8.2%), which was suggestive of poorly controlled diabetes and could have been a contributing factor for the occurrence of acute renal failure following colorectal surgery. However, this remains debateable as large cohort studies [86, 87] have shown that preoperative HbA1c levels do not predict many postoperative outcomes such as wound infection and postoperative ileus.

Ramsey et al. [64] found insulin-dependent diabetes to be a significant risk factor for the occurrence of ileus following colectomy (OR 1.40, 95% CI 1.30–1.49, p < 0.001). The increased occurrence of ileus after colectomy was attributed to damage to myenteric neurons from chronic diabetes [88], which is a common cause of diabetes-associated gastrointestinal complications. This is corroborated by previous studies which have suggested diabetes as a significant risk factor for postoperative ileus in abdominal surgery [89]. In the existing literature, there is limited support for the role of prokinetics such as erythromycin, metoclopramide, and cisapride in treating postoperative ileus [90, 91]. Current guidelines for the management of ileus are instead centred around a multi-modal approach including the use of thoracic epidural anaesthesia and analgesia intraoperatively, which allows for a reduction in postoperative administration of narcotic analgesics [92]. Furthermore, minimally invasive surgery is in itself a predictor of good outcomes as it is associated with reduced pain, and reduced opiate requirements, along with early mobilization, which contributes to a reduced occurrence of ileus [93], and should, therefore, be considered in patients with diabetes.

Finally, Anand et al. [73] concluded that diabetes was not associated with an increased occurrence of cardiac complications following colorectal surgery. However, the existing literature has demonstrated significant associations between diabetes and postoperative myocardial infarction in general surgery [94, 95]. Appropriate consideration should still be given to these complications due to their severity, with the occurrence of myocardial infarction following colorectal surgery being associated with a sixfold increase in patient mortality [96]. Hollenberg et al. [94] recommend the use of intensive Holter monitoring in high-risk patients. Similarly, careful perioperative monitoring should be considered for patients with additional risk factors in conjunction with diabetes that predispose them to postoperative myocardial infarction, including age 70 years and above, compromised renal function, and a history of congestive heart failure [96]. Additionally, in previous meta-analyses, the use of epidural analgesia has been suggested to decrease the incidence of postoperative myocardial infarction [97, 98].

Tighter glycemic control should be implemented to mitigate the negative impact of diabetes on postoperative complications after colorectal surgery. Studies concluded that the elevated risk of infectious complications in patients with hyperglycemia improves with the administration of insulin with a dose–effect relationship between insulin and the occurrence of postoperative infections [99]. Van den Berghe et al. [98] also found that intensive insulin therapy targeted at maintaining blood glucose levels between 80 and 110 mg/dL was effective in decreasing mortality in patients admitted to surgical intensive care. Furthermore, patients receiving intensive insulin therapy were less likely to require prolonged mechanical ventilation and intensive care. This has a positive impact on the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia [99] and should be considered in the postoperative management of patients with diabetes who could be at a higher risk of pulmonary related complications.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this review. First, there was a shortage of literature that evaluated the impact of diabetes on less commonly reported complications such as ileus, and urinary retention. Relevant included studies also did not provide clear definitions for urinary, pulmonary, and cardiac complications. However, we expect that these definitions are largely similar and would not have a significant influence on our results. Additionally, due to the limited baseline characteristics reported such as HbA1c levels, it was not possible to conduct meta-analysis and meta-regression for some of these complications, which could have potentially yielded useful information such as the impact of well-managed versus poorly managed diabetes on clinical outcomes. Finally, demographics and baseline characteristics of the diabetes subgroup were not disclosed in a majority of the included articles, which contributed to the heterogenicity of the data. Regardless of these limitations, this study provides a comprehensive review of the effects of diabetes on a range of postoperative complications following colorectal surgery beyond well-understood outcomes such as AL and SSI.

Conclusions

While complications such as AL and SSI are well reported on and accounted for during surgical planning [100], less commonly reported complications such as urinary retention and ileus also significantly impact surgical outcomes and should not be neglected. Not only is the prevalence of such complications higher in at-risk groups such as patients with diabetes, but the clinical impact including the length of hospital stay and treatment costs is also greater for these patients. The perioperative management plan for high-risk patients, encompassing anesthesia techniques, administration of intravenous fluids, and postoperative analgesia, should take into account a wider range of postoperative complications beyond AL and SSI to ensure desirable surgical outcomes.

Data availability

All data available upon request.

References

Clement S, Braithwaite SS, Magee MF, Ahmann A, Smith EP, Schafer RG, Hirsch IB (2004) Management of diabetes and hyperglycemia in hospitals. Diabetes Care 27(2):553–591. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.27.2.553

Saeedi P, Petersohn I, Salpea P, Malanda B, Karuranga S, Unwin N, Colagiuri S, Guariguata L, Motala AA, Ogurtsova K, Shaw JE, Bright D, Williams R (2019) Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: results from the international diabetes federation diabetes atlas 9th edition. Diabetes Res Clin Practice 157:107843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107843

Jencks SF (1992) Accuracy in recorded diagnoses. JAMA 267(16):2238–2239. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1992.03480160096043

Levetan CS, Passaro M, Jablonski K, Kass M, Ratner RE (1998) Unrecognized diabetes among hospitalized patients. Diabetes Care 21(2):246–249. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.21.2.246

Pozzilli P, Leslie RD (1994) Infections and diabetes: mechanisms and prospects for prevention. Diabet Med 11(10):935–941. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.1994.tb00250.x

Brem H, Tomic-Canic M (2007) Cellular and molecular basis of wound healing in diabetes. J Clin Invest 117(5):1219–1222. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI32169

Delamaire M, Maugendre D, Moreno M, Le Goff MC, Allannic H, Genetet B (1997) Impaired leucocyte functions in diabetic patients. Diabet Med 14(1):29–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1096-9136(199701)14:1%3c29::Aid-dia300%3e3.0.Co;2-v

Marhoffer W, Stein M, Maeser E, Federlin K (1992) Impairment of polymorphonuclear leukocyte function and metabolic control of diabetes. Diabetes Care 15(2):256–260. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.15.2.256

Geerlings SE, Hoepelman AIM (1999) Immune dysfunction in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM). FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 26(3–4):259–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-695X.1999.tb01397.x

Amri R, Dinaux AM, Kunitake H, Bordeianou LG, Berger DL (2017) Risk stratification for surgical site infections in colon cancer. JAMA Surgery 152(7):686–690. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0505

Ata A, Valerian BT, Lee EC, Bestle SL, Elmendorf SL, Stain SC (2010) The effect of diabetes mellitus on surgical site infections after colorectal and noncolorectal general surgical operations. Am Surg 76(7):697–702

Silvestri M, Dobrinja C, Scomersi S, Giudici F, Turoldo A, Princic E, Luzzati R, de Manzini N, Bortul M (2018) Modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors for surgical site infection after colorectal surgery: a single-center experience. Surg Today 48(3):338–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-017-1590-y

Penna M, Hompes R, Arnold S, Wynn G, Austin R, Warusavitarne J, Moran B, Hanna GB, Mortensen NJ, Tekkis PP (2019) Incidence and risk factors for anastomotic failure in 1594 patients treated by transanal total mesorectal excision results from the international TATME registry. Ann Surg 269(4):700–711. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002653

Lin X, Li J, Chen W, Wei F, Ying M, Wei W, Xie X (2015) Diabetes and risk of anastomotic leakage after gastrointestinal surgery. J Surg Res 196(2):294–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2015.03.017

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000097–e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Jain SR, Yaow CYL, Ng CH, Neo VSQ, Lim F, Foo FJ, Wong NW, Chong CS (2020) Comparison of colonic stents, stomas and resection for obstructive left colon cancer: a meta-analysis. Tech Coloproctol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-020-02296-5

Chin YH, Decruz GM, Ng CH, Tan HQM, Lim F, Foo FJ, Tai CH, Chong CS (2020) Colorectal resection via natural orifice specimen extraction versus conventional laparoscopic extraction: a meta-analysis with meta-regression. Tech Coloproctol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-020-02330-6

Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P (2013) The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DM, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ (1996) Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4

Nyaga VN, Arbyn M, Aerts M (2014) Metaprop: a Stata command to perform meta-analysis of binomial data. Arch Public Health 72(1):39. https://doi.org/10.1186/2049-3258-72-39

DerSimonian RLN (1986) Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 7(3):177–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2

Caulfield H, Hyman NH (2013) Anastomotic leak after low anterior resection: a spectrum of clinical entities. JAMA Surg 148(2):177–182. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurgery.2013.413

Cheng S, He B, Zeng X (2019) Prediction of anastomotic leakage after anterior rectal resection. Pak J Med Sci 35(3):830–835. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.35.3.252

Nishigori H, Ito M, Nishizawa Y, Nishizawa Y, Kobayashi A, Sugito M, Saito N (2014) Effectiveness of a transanal tube for the prevention of anastomotic leakage after rectal cancer surgery. World J Surg 38(7):1843–1851. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-013-2428-4

Cima RR, Bergquist JR, Hanson KT, Thiels CA, Habermann EB (2017) Outcomes are local: patient, disease, and procedure-specific risk factors for colorectal surgical site infections from a single institution. J Gastrointestinal Surg: Off J Soc Surg Alimentary Tract 21(7):1142–1152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-017-3430-1

Peng Xu, Lixiang Z, Linna T (2018) Analysis of related factors and etiology of surgical site infection in patients with colorectal tumors. Chinese J Nosocomial Infect 18:2803–2806

Smeenk RM, Plaisier PW, van der Hoeven JAB, Hesp WLEM (2012) Outcome of surgery for colovesical and colovaginal fistulas of diverticular origin in 40 patients. J Gastrointestinal Surg 16(8):1559–1565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-012-1919-1

Cong ZJ, Fu CG, Wang HT, Liu LJ, Zhang W, Wang H (2009) Influencing factors of symptomatic anastomotic leakage after anterior resection of the rectum for cancer. World J Surg 33(6):1292–1297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-009-0008-4

Chungang He, Qinyuan H, Lisheng C et al (2012) Analysis of risk factors for anastomotic leakage after rectal cancer anus preservation. Guangxi Med J 34(12):1692–1693

Fransgaard T, Thygesen LC, Gögenur I (2016) Increased 30-day mortality in patients with diabetes undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis 18(1):O22–O29. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.13158

Yingjiang Ye, Shan W, He Yu, Jiang Wu, Xiaodong Y, Youli W et al (2006) Analysis of influencing factors of complications related to infection at surgical site of colorectal cancer. Chinese J General Surg 21(2):122–124

Cologne KG, Skiada D, Beale E, Inaba K, Senagore AJ, Demetriades D (2014) Effects of diabetes mellitus in patients presenting with diverticulitis: clinical correlations and disease characteristics in more than 1000 patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 76(3):704–709. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000000128

García-Granero E, Navarro F, Cerdán Santacruz C, Frasson M, García-Granero A, Marinello F, Flor-Lorente B, Espí A (2017) Individual surgeon is an independent risk factor for leak after double-stapled colorectal anastomosis: an institutional analysis of 800 patients. Surgery (United States) 162(5):1006–1016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2017.05.023

Imai E, Ueda M, Kanao K, Kubota T, Hasegawa H, Omae K, Kitajima M (2008) Surgical site infection risk factors identified by multivariate analysis for patient undergoing laparoscopic, open colon, and gastric surgery. Am J Infect Control 36(10):727–731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2007.12.011

Jian L, Guiyang Z, Zhaozheng Z (2014) Analysis of risk factors for postoperative infection in patients with colorectal tumors. Chinese J Nosocomial Infect 3:693–694

Krarup PM, Nordholm-Carstensen A, Jorgensen LN, Harling H (2015) Association of comorbidity with anastomotic leak, 30-day mortality, and length of stay in elective surgery for colonic cancer: a nationwide cohort study. Dis Colon Rectum 58(7):668–676. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000000392

Zhang W, Lou Z, Liu Q, Meng R, Gong H, Hao L, Liu P, Sun G, Ma J, Zhang W (2017) Multicenter analysis of risk factors for anastomotic leakage after middle and low rectal cancer resection without diverting stoma: a retrospective study of 319 consecutive patients. Int J Colorectal Dis 32(10):1431–1437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-017-2875-8

Siyuan Li, Peng Z, Hongbo Li et al (2015) Analysis of risk factors for anastomotic leakage after colorectal cancer surgery. Adv Modern Chinese General Surg 2:163–164

Fengtao Q, Tao Z, Weizhen Y (2018) 2018 Analysis of risk factors and countermeasures for postoperative abdominal infection in patients with colorectal cancer[J]. Pract J Cancer 1:89–92

Chunhua X, Zhixing, (2015) Analysis of related factors of anastomotic leakage after radical resection of rectal cancer. China Med Guide 10:989–991

Vignali A, Fazio VW, Lavery IC, Milsom JW, Church JM, Hull TL, Strong SA, Oakley JR (1997) Factors associated with the occurrence of leaks in stapled rectal anastomoses: a review of 1,014 patients. J Am College Surg 185(2):105–113

Toyonaga T, Matsushima M, Sogawa N, Jiang SF, Matsumura N, Shimojima Y, Tanaka Y, Suzuki K, Masuda J, Tanaka M (2006) Postoperative urinary retention after surgery for benign anorectal disease: potential risk factors and strategy for prevention. Int J Colorectal Dis 21(7):676–682. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-005-0077-2

Toritani K, Watanabe J, Suwa Y, Suzuki S, Nakagawa K, Suwa H, Ishibe A, Ota M, Kunisaki C, Endo I (2019) The risk factors for urinary dysfunction after autonomic nerve-preserving rectal cancer surgery: a multicenter retrospective study at Yokohama Clinical Oncology Group (YCOG1307). Int J Colorectal Dis 34(10):1697–1703

Lu Shixu Qu, Jinmiao XY et al (2012) Analysis of pathogenic bacteria characteristics and related factors of surgical site infection after colorectal cancer surgery. Chinese J Nosocomial Infect 20:4507–4508

Defeng Y (2011) Analysis of the distribution and influencing factors of pathogenic bacteria in the surgical site of colorectal cancer. China Modern Doctor 19:147-148,154

Leyong Z (2016) The risk factors of incision infection in patients with colorectal cancer undergoing surgical treatment. Contemp Med Essays 08:2–4

Shenghong W, Luchuan C, Shengsheng Ye (2011) Analysis of risk factors and countermeasures for anastomotic leakage in 167 cases of total mesangectomy for rectal cancer. Fujian Medical Journal 6:32–33

Teoh CM, Gunasegaram T, Chan KY, Sukumar N, Sagap I (2005) Review of risk factors associated with the anastomosis leakage in anterior resection in Hospital Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. Med J Malaysia 60(3):275–280

Ke H, Xiangqian WY et al (2016) Analysis of risk factors of postoperative infection in patients with colorectal tumors. Chinese J Nosocomial Infect 4:865–866

Shirong C, Xueqing Y, Yang Z et al (2009) Analysis of risk factors for anastomotic leakage after double stapling for rectal cancer with anal preservation. Lingnan Modern Clin Sur 4:290–292

Haifeng G, Hengchun Z, Tieling Li (2014) Cause analysis and preventive measures of anastomotic leakage after TME for rectal cancer. J Mudanjiang Med College 4:62–64

News H (2019) Causes and prevention and control measures of surgical site infections after colorectal malignancies. J Clin Lab Med 3:114

Guangfa Z, Yingqiang S, Shanjing Mo (2004) Risk factors analysis and countermeasures for anastomotic leakage after total mesangectomy. Cancer 24(6):595–597

Shichao Y, Danhong X (2018) Multivariate regression analysis of factors related to anastomotic leakage after radical resection of colon cancer D3. China Modern Doctor 56(26):19-21,26

Shengjie W, Zhengjie H, Qi L (2019) Analysis of influencing factors of anastomotic leakage after laparoscopic radical resection of rectal cancer in the elderly. Electr J Comprehensive Cancer Treatment 5(3):44–48

Liwei W (2017) Analysis of risk factors for postoperative infection in patients with colorectal tumors. J Clin Med Lit 4(29):5595–5596

Jessen M, Nerstrom M, Wilbek TE, Roepstorff S, Rasmussen MS, Krarup PM (2016) Risk factors for clinical anastomotic leakage after right hemicolectomy. Int J Colorectal Dis 31(9):1619–1624

Soderback H, Gunnarsson U, Martling A, Hellman P, Sandblom G (2019) Incidence of wound dehiscence after colorectal cancer surgery: results from a national population-based register for colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis 34(10):1757–1762

Chang HR, Shih SC, Lin FM (2012) Impact of comorbidities on the outcomes of older patients receiving rectal cancer surgery. Int J Gerontol 6(4):285–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijge.2012.05.006

Rodriguez-Ramirez SE, Uribe A, Ruiz-Garcia EB, Labastida S, Luna-Perez P (2006) Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after preoperative chemoradiation therapy and low anterior resection with total mesorectal excision for locally advanced rectal cancer. Rev Investigacion Clin 58(3):204–210

Parthasarathy M, Greensmith M, Bowers D, Groot-Wassink T (2017) Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after colorectal resection: a retrospective analysis of 17 518 patients. Colorectal Dis 19(3):288–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.13476

Ramsey T, Giaccio SL, Navarro FA (2017) Postoperative complications of colectomy in diabetes patients. Austin J Surg 4(4): 1111. ISSN:2381–9030

Xin W, Jianping Z, Danhua Z, Weiwei S, Ming D (2014) Analysis of risk factors for anastomotic leakage after rectal cancer surgery (with a report of 506 cases). Chinese J Pract Surg 34(9):876–879

Mingxia L, Shiying Y, Ying H (2014) Analysis of the etiology and influencing factors of infection at the surgical site of colorectal cancer. Chinese Journal of Nosocomial Infection 24(9):2244–2246

Nakamura T, Mitomi H, Ihara A, Onozato W, Sato T, Ozawa H, Hatade K, Watanabe M (2008) Risk factors for wound infection after surgery for colorectal cancer. World J Surg 32(6):1138–1141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-008-9528-6

Gachabayov M, Senagore AJ, Abbas SK, Yelika SB, You K, Bergamaschi R (2018) Perioperative hyperglycemia: an unmet need within a surgical site infection bundle. Tech Coloproctol 22(3):201–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-018-1769-2

Uchino M, Ikeuchi H, Bando T, Chohno T, Sasaki H, Horio Y, Nakajima K, Takesue Y (2019) Efficacy of preoperative oral antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of surgical site infections in patients with crohn disease: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 269(3):420–426. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002567

Liu Y, Wan X, Wang G, Ren Y, Cheng Y, Zhao Y, Han G (2014) A scoring system to predict the risk of anastomotic leakage after anterior resection for rectal cancer. J Surg Oncol 109(2):122–125. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.23467

Jun Li, Shengchang J, Deliang Y, Meng J (2014) Analysis of risk factors for anastomotic leakage after primary resection of left colon cancer and acute intestinal obstruction. Chinese J Practical Diagnosis Therapy 28(7):687–688

Pasam RT, Esemuede IO, Lee-Kong SA, Kiran RP (2015) The minimally invasive approach is associated with reduced surgical site infections in obese patients undergoing proctectomy. Tech Coloproctol 19(12):733–743

Anand N, Chong CA, Chong RY, Nguyen GC (2010) Impact of diabetes on postoperative outcomes following colon cancer surgery. J Gen Intern Med 25(8):809–813. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1336-7

Stein KB, Snyder CF, Barone BB, Yeh HC, Peairs KS, Derr RL, Wolff AC, Brancati FL (2010) Colorectal cancer outcomes, recurrence, and complications in persons with and without diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Digest Dis Sci 55(7):1839–1851

Martin ET, Kaye KS, Knott C, Nguyen H, Santarossa M, Evans R, Bertran E, Jaber L (2016) Diabetes and risk of surgical site infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 37(1):88–99. https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2015.249

Koziel H, Koziel MJ (1995) Pulmonary complications of diabetes mellitus. Pneumonia Infect Dis Clin North Am 9(1):65–96

Rello J, Ollendorf DA, Oster G, Vera-Llonch M, Bellm L, Redman R, Kollef MH (2002) Epidemiology and outcomes of ventilator-associated pneumonia in a large US database. Chest 122(6):2115–2121. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.122.6.2115

Thomas CP, Ryan M, Chapman JD, Stason WB, Tompkins CP, Suaya JA, Polsky D, Mannino DM, Shepard DS (2012) Incidence and cost of pneumonia in medicare beneficiaries. Chest 142(4):973–981. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.11-1160

Lin TL, Chen GD, Chen YC, Huang CN, Ng SC (2012) Aging and recurrent urinary tract infections are associated with bladder dysfunction in type 2 diabetes. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 51(3):381–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjog.2012.07.011

Zmora O, Madbouly K, Tulchinsky H, Hussein A, Khaikin M (2010) Urinary bladder catheter drainage following pelvic surgery–is it necessary for that long? Dis Colon Rectum 53(3):321–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/DCR.06013e3181c7525c

Golbidi S, Laher I (2010) Bladder dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Front Pharmacol 1:136. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2010.00136

Bhatia NN, Bergman A (1984) Urodynamic predictability of voiding following incontinence surgery. Obstet Gynecol 63(1):85–91

Dawson T, Lawton V, Adams E, Richmond D (2007) Factors predictive of post-TVT voiding dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 18(11):1297–1302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-007-0324-x

Gupta S, Gambhir JK, Kalra O, Gautam A, Shukla K, Mehndiratta M, Agarwal S, Shukla R (2013) Association of biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress with the risk of chronic kidney disease in Type 2 diabetes mellitus in North Indian population. J Diabetes Complications 27(6):548–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2013.07.005

Schneider MP, Ott C, Schmidt S, Kistner I, Friedrich S, Schmieder RE (2013) Poor glycemic control is related to increased nitric oxide activity within the renal circulation of patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 36(12):4071–4075. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc13-0806

Jones CE, Graham LA, Morris MS, Richman JS, Hollis RH, Wahl TS, Copeland LA, Burns EA, Itani KMF, Hawn MT (2017) Association between preoperative hemoglobin A1c Levels, postoperative hyperglycemia, and readmissions following gastrointestinal surgery. JAMA Surg 152(11):1031–1038. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2017.2350

King JT Jr, Goulet JL, Perkal MF, Rosenthal RA (2011) Glycemic control and infections in patients with diabetes undergoing noncardiac surgery. Ann Surg 253(1):158–165. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f9bb3a

Krishnan B, Babu S, Walker J, Walker AB, Pappachan JM (2013) Gastrointestinal complications of diabetes mellitus. World J Diabetes 4(3):51–63. https://doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v4.i3.51

Ozdemir AT, Altinova S, Koyuncu H, Serefoglu EC, Cimen IH, Balbay DM (2014) The incidence of postoperative ileus in patients who underwent robotic assisted radical prostatectomy. Cent Eur J Urol 67(1):19–24. https://doi.org/10.5173/ceju.2014.01.art4

Lubawski J, Saclarides T (2008) Postoperative ileus: strategies for reduction. Ther Clin Risk Manag 4(5):913–917. https://doi.org/10.2147/tcrm.s2390

Bungard TJ, Kale-Pradhan PB (1999) Prokinetic agents for the treatment of postoperative ileus in adults: a review of the literature. Pharmacother J Human Pharmacol Drug Therapy 19(4):416–423. https://doi.org/10.1592/phco.19.6.416.31040

Luckey A, Livingston E, Taché Y (2003) Mechanisms and treatment of postoperative ileus. Arch Surg 138(2):206–214. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.138.2.206

Watt DG, McSorley ST, Horgan PG, McMillan DC (2015) Enhanced Recovery after surgery: which components, if any, impact on the systemic inflammatory response following colorectal surgery?: a systematic review. Medicine 94(36):e1286. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000001286

Hollenberg M, Mangano DT, Browner WS, London MJ, Tubau JF, Tateo IM, Leung JM, Krupski WC, Rapp JA, Hedgcock MW, Verrier ED, Merrick S, Meyer ML, Levenson L, Wong MG, Layug E, Li J, Franks ME, Wellington YC, Balasubramanian M, Cembrano E, Velasco W, Pineda N, Katiby SN, Miller T, von Ehrenburg W, O’Kelly BF, Szlachcic J, Knight AA, Fegert V, Goehner P, Harris DN, Siliciano D, Mark NH, Smith R, Helman J, Tice J, Fox C, Heithaus A, Showstack J, Nicoll DC, Heineken P, Massie B, Chatterjee K, Fairley HB, Way LW, Winkelstein W (1992) Predictors of postoperative myocardial ischemia in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. JAMA 268(2):205–209. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1992.03490020053030

Ali MJ, Davison P, Pickett W, Ali NS (2000) ACC/AHA guidelines as predictors of postoperative cardiac outcomes. Can J Anaesth 47(1):10–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03020725

Moghadamyeghaneh Z, Mills SD, Carmichael JC, Pigazzi A, Stamos MJ (2015) Risk factors of postoperative myocardial infarction after colorectal surgeries. Am Surg 81(4):358–364

Beattie WS, Badner NH, Choi P (2001) Epidural analgesia reduces postoperative myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis. Anesth Analg 93(4):853–858. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000539-200110000-00010

de Leon-Casasola OA, Lema MJ, Karabella D, Harrison P (1995) Postoperative myocardial ischemia: epidural versus intravenous patient-controlled analgesia: a pilot project. Regional Anesthesia: J Neural Blockade Obstetrics, Surg, Pain Control 20(2):105–112. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-00115550-199520020-00005

Kwon S, Thompson R, Dellinger P, Yanez D, Farrohki E, Flum D (2013) Importance of perioperative glycemic control in general surgery: a report from the surgical care and outcomes assessment program. Ann Surg 257(1):8–14. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31827b6bbc

van den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, Verwaest C, Bruyninckx F, Schetz M, Vlasselaers D, Ferdinande P, Lauwers P, Bouillon R (2001) Intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 345(19):1359–1367. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa011300

Koenig SM, Truwit JD (2006) Ventilator-associated pneumonia: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Clin Microbiol Rev 19(4):637–657. https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.00051-05

Mok HT, Ong ZH, Yaow CYL, Ng CH, Buan BJL, Wong NW, Chong CS (2020) Indocyanine green fluorescent imaging on anastomotic leakage in colectomies: a network meta-analysis and systematic review. Int J Colorectal Dis. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-020-03723-7

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by DJHT, HTM, CYLY and CHN. The first draft of the manuscript was written by all authors and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals by any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tan, D.J.H., Yaow, C.Y.L., Mok, H.T. et al. The influence of diabetes on postoperative complications following colorectal surgery. Tech Coloproctol 25, 267–278 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-020-02373-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-020-02373-9