Abstract

Background

The Japan Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guidelines for Antiemesis 2023 was extensively revised to reflect the latest advances in antineoplastic agents, antiemetics, and antineoplastic regimens. This update provides new evidence on the efficacy of antiemetic regimens.

Methods

Guided by the Minds Clinical Practice Guideline Development Manual of 2017, a rigorous approach was used to update the guidelines; a thorough literature search was conducted from January 1, 1990, to December 31, 2020.

Results

Comprehensive process resulted in the creation of 13 background questions (BQs), 12 clinical questions (CQs), and three future research questions (FQs). Moreover, the emetic risk classification was also updated.

Conclusions

The primary goal of the present guidelines is to provide comprehensive information and facilitate informed decision-making, regarding antiemetic therapy, for both patients and healthcare providers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Japan Society of Clinical Oncology Guidelines for Antiemetic Therapy was developed to appropriately evaluate and manage chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting and improve treatment efficacy, thereby improving patient quality of life (QOL) and, ultimately, patient prognosis. The initial Japan Society of Clinical Oncology (JSCO) Clinical Practice Guidelines for Antiemesis were published in 2010, with updates in 2015 (revised edition, version 2) and 2018 (revised edition, version 2.2) [1, 2]. Revisions were made in the third edition to reflect new evidence on antineoplastic agents, antiemetics, antineoplastic regimens. In addition, by appropriately assessing the balance between the benefits and harms of different antiemetic therapies based on the evidence, these guidelines aim to facilitate informed decision-making regarding antiemetic therapy for both patients and healthcare providers.

Methods

Guiding principles for the development

The antiemetic guideline update committee consisted of 23 working group members and 18 systematic review team members who are multidisciplinary healthcare professionals with expertise in antiemetic research (physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and epidemiologists), two patient advocates, and two secretaries.

In developing and revising these guidelines, the basic approach is to follow the 'Minds Clinical Practice Guideline Development Manual 2017’ [3]. Questions are developed based on the key clinical issues Table 1. Systematic reviews of each question are conducted, and recommendations are determined based on the obtained results [4]. The quality of evidence and definitions are presented in Table 2. The recommendations are generally presented based on a combination of the direction of the recommendation (two directions) and the strength of the recommendation (two levels), as listed in Table 3. The strengths of the recommendation, quality of evidence, and agreement rate were then concurrently stated. The consensus-building method involves web voting using the GRADE grid. Consensus is achieved when the concentration of votes for a specific statement pertaining to each item exceeds 80%, thereby influencing the determination of recommendations [5]. The working group members and patient advocates conducted the voting. If a consensus was not reached in the first round of voting, discussions were held, and a second round of voting was conducted. If consensus was not reached in the second round, the process and summary of the results were documented in the statement.

The classification and terminology of the questions in this guideline

The questions in this guideline comprise “background questions (BQ),” “clinical questions (CQ),” and “future research questions (FQ).” BQs represent fundamental knowledge that includes clinical characteristics, epidemiological features, and the overall flow of medical practice. The BQs encompass widely understood issues requiring documentation in the guidelines. CQs focus on the significant but less familiar issues based on the recent evidences wherein a systematic review has been performed, and evidence-based recommendations can be provided. FQs are unresolved issues wherein a systematic review could not be completed owing to insufficient evidence or other constraints, precluding the formulation of evidence-based recommendations.

Emetic risk classification of the antineoplastic agents

The classification of emetogenicity for antineoplastic agents is primarily based on the incidence of emesis occurring within 24 h following the administration of antineoplastic agents without prophylactic antiemetic administration. High emetic risk (> 90% patients experience acute emesis), moderate emetic risk (30 < –90% of patients experience acute emesis), low emetic risk (10–30% of patients experience acute emesis), and minimal emetic risk (< 10% of patients experience acute emesis) are determined through non-systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials, analysis of product labeling, the evaluation of emetic classification in other international guidelines, and informal consensus.

Literature search

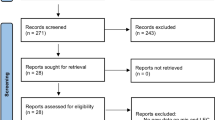

For this update, we conducted a literature search covering the period from January 1, 1990, to December 31, 2020, using PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Igaku Chuo Zasshi (ICHUSHI) databases. For questions related to nonpharmacological therapy and patient support, an additional search was conducted using CINAHL. The formula used to search the literature is published on the JSCO website [4].

The priority for literature adoption was as follows: (1) randomized controlled trials, (2) non-randomized comparative trials, (3) single-arm trials, (4) case–control studies, and (5) observational studies that allow the extraction of data for both the group receiving the antiemetic therapy under investigation and the group not receiving it. Case reports and case series studies of poor quality were excluded.

Conflicts of interest for the guideline

In accordance with the JSCO guidelines for the management of conflicts of interest (COIs), the members of the guideline update working group and those of the systematic review team submitted self-disclosures of financial COIs. The COI Committee reviewed these submissions and confirmed that none of the members had any significant financial COI (http://www.jsco-cpg.jp/).

If a voting member had a COI, such as being a lead author or a corresponding author of a paper related to the evidence that forms the basis of the recommendation, or if they had a financial COI with the company or companies involved in the manufacture or sale of the related drugs or medical devices beyond the criteria outlined in the Japan Medical Association’s “Guidance on Eligibility Criteria for Participation in Clinical Practice Guideline Development,” they abstained from voting.

Results

Emetic risk classification of antineoplastic agents

The emetic risks of intravenous and oral antineoplastic agents are shown in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. In addition, the emetogenic properties of certain combination chemotherapies are depicted.

Background questions and future research questions with statements

BQs and FQs are shown in Table 6.

Clinical questions and recommendations

CQ1: Is the addition or concurrent use of olanzapine recommended for the prevention of nausea and vomiting associated with highly emetogenic risk antineoplastic agents using a triplet antiemetic regimen (a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist + an NK1 receptor antagonist + dexamethasone)?

Recommendation: We recommend the addition or concurrent use of olanzapine to a triplet antiemetic regimen to prevent nausea and vomiting associated with antineoplastic agents with high emetogenic risk.

[Strength of recommendation: 1; Quality of evidence: B; Agreement rate: 95.7% (22/23)].

CQ2: Is it recommended to shorten the administration duration of dexamethasone to one day for the prevention of nausea and vomiting associated with highly emetogenic risk antineoplastic agents?

Recommendation: We suggest shortening the duration of dexamethasone administration to one day to prevent the nausea and vomiting associated with antineoplastic agents with a high emetogenic risk, especially in the case of AC regimens.

[Strength of recommendation: 2; Quality of evidence: B, Agreement rate: 95.5% (21/22)].

CQ3: Is the administration of an NK1 receptor antagonist recommended for the prevention of nausea and vomiting associated with moderately emetogenic risk antineoplastic agents?

Recommendation: We recommend the administration of NK1 receptor antagonists to prevent the nausea and vomiting associated with carboplatin regimens in moderate-emetogenic-risk antineoplastic agents.

[Strength of recommendation: 1; quality of evidence: A, Agreement rate: 100% (22/22)].

CQ4: Is the addition or concurrent use of olanzapine to the triplet antiemetic regimen (a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist + an NK1 receptor antagonist + dexamethasone) recommended for the prevention of nausea and vomiting associated with moderately emetogenic risk antineoplastic agents?

Recommendation: We suggest the addition or concurrent use of olanzapine to the triplet antiemetic regimen to prevent the nausea and vomiting associated with moderate-risk emetogenic antineoplastic agents.

[Strength of recommendation: 2; Quality of evidence: C, Agreement rate: 87.5% (21/24)].

CQ5: Is the addition or concurrent use of olanzapine to the doublet antiemetic regimen (a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist + dexamethasone) recommended for the prevention of nausea and vomiting associated with moderately emetogenic risk antineoplastic agents?

Recommendation: No consensus was reached.

[Strength of recommendation: not granted; quality of evidence: C, Agreement rate: N/A (Two votes were taken. No consensus was reached.)].

CQ6: Is it recommended to shorten the administration duration of dexamethasone to one day for the prevention of nausea and vomiting associated with moderate emetogenic risk antineoplastic agents?

Recommendation: We recommend shortening the duration of dexamethasone administration to one day to prevent the nausea and vomiting associated with moderate-risk emetogenic antineoplastic agents, especially when administering palonosetron as a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist.

[Strength of recommendation: 1; Quality of evidence: B, Agreement rate: 90.5% (19/21)].

CQ7: Is it recommended to omit the administration of an NK1 receptor antagonist for the prevention of nausea and vomiting in R ± CHOP regimens?

Recommendation: We suggest not to omit the administration of an NK1 receptor antagonist for the prevention of nausea and vomiting in R ± CHOP regimens.

[Strength of recommendation: 2; Quality of evidence: C; Agreement rate: 91.7% (22/24)].

CQ8: Is the administration of metoclopramide recommended for breakthrough nausea and vomiting?

Recommendation: We suggest the administration of metoclopramide for breakthrough nausea and vomiting.

[Strength of recommendation: 2; Quality of evidence: B, Agreement rate: 95.8% (23/24)].

CQ9: Is daily antiemetic therapy recommended for patients receiving daily intravenous administrations of cytotoxic antineoplastic agents?

Recommendation: We recommend the implementation of daily antiemetic therapy in patients receiving daily intravenous cytotoxic antineoplastic agents.

[Strength of recommendation: 1; Quality of evidence: D, Agreement rate: 95.8% (23/24)].

CQ10: Is the concurrent use of non-pharmacological therapy recommended for the prevention of nausea and vomiting?

Recommendation: We suggest not to perform non-pharmacological interventions for the management of nausea and vomiting.

[Strength of recommendation: 2; Quality of evidence: D, Agreement rate: 83.3% (20/24)].

CQ11: Is non-pharmacological therapy recommended for anticipatory nausea and vomiting?

Recommendation: We suggest not to perform non-pharmacological interventions for anticipatory nausea and vomiting.

[Strength of recommendation: 2; Quality of evidence: D, Agreement rate: 95.8% (23/24)].

CQ12: Is the use of patient-reported outcomes recommended for the assessment of nausea and vomiting?

Recommendation: We recommend using patient-reported outcomes to assess nausea and vomiting.

[Strength of recommendation: 1; quality of evidence: B, Agreement rate: 100% (22/22)].

Summary

Adult antiemetic dosing information is listed in Table 7, and the standard model for antiemetic treatment regimens is detailed in the four diagrams shown in Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of antiemetic treatments for intravenous antineoplastic agents. * Alternative dexamethasone dose. ** If first generation 5HT3RA is administered. *** Optional dose of dexamethasone. The diagrams show standard examples of antiemetic treatment regimens. Flexible modifications are necessary, depending on the specific condition of each patient. The recommended dose of dexamethasone has been specified for oral (intravenous) administration. Intravenous dexamethasone includes 3.3 mg/mL of dexamethasone out of a total of 4 mg/mL of dexamethasone sodium phosphate

Discussion

This manuscript presents an English summary of the Japan Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guidelines for Antiemesis 2023.

In the present guidelines, the emetic risk classification has been revised to incorporate new antineoplastic agents and chemotherapy regimens. Currently, classification is based on the emetic risk during the acute phase without antiemetic therapy. However, obtaining such data during clinical trials for the development of antineoplastic agents is challenging.

It is important to note that sacituzumab govitecan and trastuzumab deruxtecan are at the high end of the moderate category for emetogenicity, and with the accumulation of future clinical trial results on antiemetic therapy, there is a possibility that they may be considered as candidates for the application of triple combination therapy including NK1 receptor antagonists. Currently, these agents are classified as having moderate emetic risk due to insufficient evidence regarding their emetogenic potential. However, contingent on the results of future clinical trials, they may be reclassified into the high emetic risk category. Therefore, when using these agents, it is crucial to carefully monitor the patient's condition and flexibly adjust the antiemetic therapy as needed, such as considering the concomitant use of NK1 receptor antagonists. As new evidence on antiemetic therapy accumulates, the content of the guidelines will need to be updated accordingly. Readers are advised to stay informed about the latest findings regarding emetogenicity.

The emetogenic properties of certain combination chemotherapy are classified based on the incidence and severity of emesis observed with antiemetic therapy commonly used in clinical trials and in real-world clinical practice.

We had initially proposed 15 CQs for this update. However, because insufficient evidence prevented the completion of a systematic review for three of them, the three were categorized as FQs. Urgent attention is warranted for conducting clinical trials to address all three questions.

Prevention of nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing cancer chemotherapy is critical not only for treatment efficacy, but also for maintaining the overall quality of life. These guidelines are intended to promote and facilitate appropriate antiemetic therapy in clinical practice and serve as a supportive resource for clinicians and medical staff to make compassionate decisions tailored to individual patients undergoing cancer chemotherapy. By promoting the implementation of effective strategies, we hope to contribute to the overall success of cancer treatment and enhance the well-being of the patients undergoing this challenging therapeutic journey.

References

Takeuchi H, Saeki T, Aiba K et al (2016) Japanese Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical practice guidelines 2010 for antiemesis in oncology: Executive summary. Int J Clin Oncol 21(1):1–12

Aogi K, Takeuchi H, Saeki T et al (2021) Optimizing antiemetic treatment for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in Japan: Update summary of the 2015 Japan Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guidelines for Antiemesis. Int J Clin Oncol 26(1):1–17

Minds Clinical Practice Guideline Development Manual 2017. https://minds.jcqhc.or.jp/ (Japanese) [accessed April 1, 2024]

Japan Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical practice guidelines for antiemesis. http://www.jsco-cpg.jp/item/29/index.html (Japanese) [accessed April 1, 2024]

Jaeschke R, Guyatt GH, Dellinger P et al (2008) Use of GRADE grid to reach decisions on clinical practice guidelines when consensus is elusive. BMJ 337:744. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a744

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the members of the Systematic Review committee (Mr. Takeshi Aoyama, Ms. Chisato Ichikawa, Dr. Arisa Iba, Ms.Yoshiko Irie, Ms. China Ogura, Dr. Jun Kako, Dr. Rena Kaneko, Dr. Masamitsu Kobayashi, Dr. Tetsuo Saito, Dr. Kazuhisa Nakashima, Dr. Toshinobu Hayashi, Dr. Saki Harashima, Ms. Naomi Fujikawa, Dr. Yoshiharu Miyata, Mr. Michiyasu Murakami, Dr. Shun Yamamoto, Ms.Ayako Yokomizo and Dr. Saran Yoshida) for their valuable contributions to this work. We would like to express our gratitude to Ms. Natsuki Fukuda and Ms. Kyoko Hamada for their invaluable support as secretaries of the Working Group.

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Mr. Naohiko Yamaguchi and Ms. Yuko Mitsuoka for their invaluable assistance in conducting the systematic literature search for the purposes of this paper. Their assistance and dedication contributed significantly to the success of this study. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for the English language editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Eriko Satomi received honoraria from Shionogi & Co., Ltd. Masayuki Takeda received honoraria from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., AstraZeneca K.K., Novartis Pharma K.K., Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Bayer. Takako Eguchi Nakajima received research funding from KBBM, Inc. and Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Junichi Nishimura received honoraria from Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Narikazu Boku received honoraria from Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Bristol Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Eli Lilly Japan K.K. Koji Matsumoto received honoraria from MSD K.K., Kyowa Kirin Co., Ltd., and Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. as well as research funding from Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., MSD K.K., Gilead Sciences, Inc., and Eli Lilly Japan K.K. Nobuyuki Yamamoto received honoraria from MSD K.K., Accuray Japan K.K., AstraZeneca K.K., Abbvie Inc., Amgen Inc., Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Guardant Health Japan Corp., Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Chugai Foundation for Innovative Drug Discovery Science, Lao Tsumura Co., Ltd., Terumo Corporation, Eli Lilly Japan K.K., Nippon Kayaku Co., Ltd., Novartis AG, Pfizer Global Supply Japan Inc., Merck Biopharma Co., Ltd, Pfizer Global Supply Japan Inc., Merck Biopharma Co., Ltd., Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K., and USACO Corporation, as well as legal fees in case of iawsuit from Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Boehringer Ingelheim Japan, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Kyowa Kirin Co., Ltd., Nippon Kayaku Co., Ltd., Prime Research Institute for Medical RWD, Inc., AstraZeneca K.K., and A2 Healthcare Corporation. Kenjiro Aogi received honoraria from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Eisai Co., Ltd., AstraZeneca K.K., Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Novartis Pharma K.K., Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., Mochida Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Pfizer Japan Inc. and Eli Lilly Japan K.K., as well as research funding from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Eisai Co., Ltd. and Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Iihara, H., Abe, M., Wada, M. et al. 2023 Japan Society of clinical oncology clinical practice guidelines update for antiemesis. Int J Clin Oncol 29, 873–888 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-024-02535-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-024-02535-x