Abstract

Background

Despite the close link between cigarette smoking and the development of gastric cancer, little is known about the effects of cigarette smoking on surgical outcomes after gastric cancer surgery. The aim of this study was to investigate whether preoperative smoking status and the duration of smoking cessation were associated with short-term surgical consequences in gastric cancer surgery.

Methods

Among 1,489 consecutive patients, 1,335 patients who underwent curative radical gastrectomy at the Samsung Medical Center between January and December 2009 were included in the present study. The smoking status was determined using questionnaires before surgery. Smokers were divided into four groups according to the duration of smoking cessation preoperatively (<2, 2–4, 4–8, and >8 weeks). The primary endpoint was postoperative complications (wound, lung, leakage, and bleeding); secondary endpoints were 3-year recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS).

Results

Five hundred twenty-two patients (39.1 %) were smokers. Smokers had a significantly higher overall incidence of postoperative complications than nonsmokers (12.3 vs. 5.2 %, P < 0.001, respectively), especially in impaired wound healing, pulmonary problems, and leakage. Smokers also had more severe complications than nonsmokers. After adjusting for other risk factors, the odds ratio (95 % CI) for the development of postoperative complications in the subgroups who stopped smoking <2 weeks, 2–4, 4–8, and >8 weeks preoperatively were 3.35 (1.92–5.83), 0.99 (0.22–4.38), 2.18 (1.00–4.76), and 1.32 (0.70–2.48), respectively, compared with the nonsmokers. There were no significant differences in 3-year RFS (P = 0.884) and OS (P = 0.258) between smokers and nonsmokers.

Conclusions

Preoperative smoking cessation for at least 2 weeks will help to reduce the incidence of postoperative complications in gastric cancer surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the fourth most common cancer in the world, and has the second highest mortality of all cancers [1]. Although its incidence and mortality rate have been decreasing in recent decades, its incidence in Asia (such as in Korea, Japan, and China) is still high [2–4]. According to recent studies, smoking is the most important behavioral risk factor for the development of gastric cancer [5–7]. In this respect, high incidences of gastric cancer may be associated with the high smoking rates, especially in men, in these Eastern countries [8–10], although they are influenced by other environmental factors as well [3, 11]. Despite the many studies that have been performed on the close relationship between smoking and the development of gastric cancer, little is known about the specific anatomical features of gastric cancer when it develops in smoking patients, the complications which may arise, or the prognosis after gastric cancer surgery, which are associated with smoking history.

Smoking has been reported to be a risk factor for other cancers in addition to gastric cancer and as a major risk factor for postoperative complications [12–14]. Smoking is known to have an adverse effect on the pulmonary, circulatory, and immunologic systems, and on wound healing, and it has been reported that cessation of smoking before surgery helps improve postoperative results [15]. However, there have been few studies on the duration of smoking cessation required before surgery to effectively reduce postoperative complications. There has been almost no study on stomach cancer patient groups in particular. Due to the lack of clear information on this subject, surgeons and patients do not pay attention to the effects of smoking cessation before surgery. Many clinicians may not feel the need for smoking cessation before surgery, and some patients lack the motivation to stop smoking [16]. However, postoperative complications can be stressful to patients and surgeons and also life-threatening; they also lead to prolonged hospital stays, which impose an economic burden [17]. In the present study, we investigated the relationship between smoking history before surgery and postoperative complications as well as prognosis in gastric cancer patients in a single center.

Methods

Patients

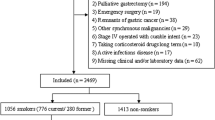

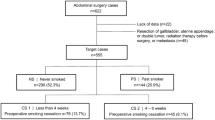

A total of 1,489 patients were diagnosed with primary gastric adenocarcinoma and underwent radical gastrectomy between January 2009 and December 2009 at the Samsung Medical Center. Prospectively collected data from medical records were reviewed and analyzed retrospectively. All of the patients were histologically confirmed as having gastric adenocarcinoma before surgery and radiologic examinations (e.g., computed tomography or positron emission tomography–computed tomography) were also performed to determine the stage of the disease. Out of 1,489 patients, 1,335 patients who underwent R0 resection with no evidence of distant metastasis were enrolled in the study while ensuring that no subject of the study had undergone preoperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy. The smoking history of each patient was first surveyed objectively by a questionnaire that was performed prior to surgery and collected in an interview conducted by medical personnel if the patient’s answers to the questionnaire were not available. Patients were divided into two groups, smokers and nonsmokers, depending on their answers. Smokers were defined as current or former smokers, and nonsmokers were considered to be those who had never smoked previously. In the smoker group, the duration of the smoke-free period before the surgery was recorded to elucidate whether there is a clinically useful duration of preoperative smoking cessation that reduces postoperative complications. Smokers were subdivided into four subgroups according to their smoking cessation period before the surgery (<2, 2 to <4, 4 to <8, and ≥8 weeks) because the interval from the diagnosis of gastric cancer to the surgery in our hospital was approximately 2–8 weeks (Fig. 1). After the diagnosis of gastric cancer, patients with a recent smoking cessation history (<8 weeks before the surgery) were those who had decided to stop smoking voluntarily or had followed the surgeon’s advice on smoking cessation at the outpatient visit. Patients in the ≥8 weeks subgroup, on the other hand, were those who had already stopped smoking several months to years ago for various reasons. Active and passive smoking were strictly prohibited for all patients during the hospital stay, and in this study there were no cases of resumption of smoking during the hospital stay.

Assessment of pre- and postoperative factors

Before surgery, clinical parameters were collected such as gender, age, body mass index (BMI), comorbidities [hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)], American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, and pulmonary function test (PFT).

Hospital stay, histopathologic results, and history of postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy were surveyed after the surgery.

Definitions of outcomes

Any postoperative complications were considered to have manifested themselves by 30 days after surgery, and the following four events were surveyed: surgical wound complications (surgical site infection and dehiscence, except for seroma), pulmonary complications (atelectasis or pneumonia), leakage (anastomotic or stump leakage), and bleeding (intra-abdominal or intra-luminal bleeding). During hospitalization and in the outpatient department, each complication was diagnosed by a clinician and through additional investigations (radiography, laboratory tests) based on the following criteria: (1) surgical site infections were defined as infections that occur at the surgical site within 30 days after operation, which were categorized into three types (superficial, deep, and organ-space) according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [18]; (2) pulmonary complications were confirmed by chest X-ray with clinical symptoms; (3) leakages were identified by radiologic findings such as computed tomography or a water-soluble contrast study in suspected patients; (4) serious bleeding was discovered by drainage with laboratory findings. The severity of complications was graded according to the Clavien–Dindo classification [19, 20].

The secondary endpoints relating to postoperative prognosis were overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS). OS was calculated as the interval from surgery to death (irrespective of cause), and losses to follow-up were censored. RFS was measured from the date of the surgery to the date of the first clinically detected recurrence.

Follow-up

All patients were followed up at the outpatient department 1 month after radical gastrectomy, and 3 and 6 months after surgery, and then every 6 months afterwards. History-taking, physical examinations, blood tests (e.g., complete blood count, liver function tests, and tumor markers), upper (lower) gastrointestinal tract endoscopy, and radiologic examinations (e.g., chest X-rays, computed tomography, or positron emission tomography–CT) were selectively conducted during the follow-up period. The median follow-up period was 39.0 months (range 0–46).

Statistical analysis

Data on clinicopathologic characteristics were gathered from the nonsmokers and smokers, and a comparative analysis between the two groups was performed using an independent samples t test for continuous variables and a chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. To assess postoperative complications, the odds ratios (OR) according to smoking cessation period before surgery were compared with the nonsmoker group as a reference group using logistic regression analysis. Multivariate analysis was adjusted for the significant confounders (sex, age, existence of comorbidity, ASA classification, and FEV1/FVC).

The Kaplan–Meier survival curve was used to analyze OS and RFS, and a comparison between groups was performed using the log-rank test. Analysis of the data was performed using SPSS software version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and the statistical significance was determined with a 5 % significance level.

Results

Clinicopathologic characteristics

A total of 1,335 patients were enrolled in this study, of whom 522 (39.1 %) patients were smokers and 813 (60.9 %) patients were nonsmokers. There were significant differences between the two groups in gender, comorbidity (COPD), ASA score, PFT, and hospital stay. In the smoker group, there were higher proportions of male patients (P < 0.001) and patients with COPD (P = 0.018). The average hospital stay of the nonsmoker group was shorter than that of the smoker group (9.3 ± 4.0 vs. 10.1 ± 6.3 days, P = 0.013, respectively) (Table 1).

In the histopathologic comparison, there was no significant difference in size, site, and stage of tumor between the two groups. In the smoker group, advanced gastric cancer and intestinal type (according to the Lauren classification) were more common than they were in the nonsmoker group (P = 0.006 and P < 0.001, respectively) (Table 2).

Postoperative complications

Postoperative complications occurred in 106 (7.9 %) patients out of a total of 1,335 patients; 42 cases (3.1 %) were in the nonsmoker group and 64 cases (4.8 %) were in the smoker group. Pulmonary complications occurred most frequently, in 61 patients (4.6 %), and wound complications, leakage, and bleeding followed in decreasing order of frequency. Among pulmonary complications, atelectasis was the most common, and pneumonia occurred in 15 patients (smokers: n = 9, nonsmokers: n = 6). Patients with wound complications were treated with antibiotics, repeated wound dressings, and debridement or re-suture in severe cases. Organ-space surgical site infection was observed in 7 patients (smokers: n = 5, nonsmokers: n = 2), and most of them were cured with percutaneous drainage and antibiotic therapy. Thirteen patients who had stump or anastomotic site leakage were resolved by conservative treatment, such as drainage or observation, but another two patients with leakage in the smoker group needed to undergo re-operation. There were five cases of re-operation due to postoperative intra-peritoneal bleeding, and the other three cases of bleeding were improved by endoscopic hemostasis or conservative management. Among all of the patients, only five had two complications, and one patient had three complications. When comparing the overall incidence of postoperative complications according to smoking history, the overall incidence rate was significantly higher in the smoker group than in the nonsmoker group (12.3 vs. 5.2 %, P < 0.001, respectively). When comparing the incidence rates of each complication type, the incidence rates of wound complication, pulmonary complication, and leakage were also higher in the smoker group. Moreover, the severity of complications was significantly different between the two groups, and the morbidity rate (≥ grade II) was significantly higher in the smoker group than in the nonsmoker group (7.9 vs. 2.6 %, P < 0.001, respectively) (Table 3).

Patients in the smoker group were subdivided into four subgroups according to the length of the smoking cessation period before surgery, and the incidences of postoperative complications were also evaluated for each group. The incidences of any complication among the smokers who stopped ≥8 weeks preoperatively, 4–8 weeks preoperatively, 2 to <4 weeks preoperatively, and <2 weeks preoperatively were 9.3, 12.2, 5.0, and 16.4 %, respectively (P < 0.001), and the incidence of postoperative complications was significantly higher, especially in the subgroup with <2 weeks of smoking cessation preoperatively. There were also significant differences in each complication type among the nonsmokers and the subgroups of smokers, except for bleeding. Additionally, upon comparing the severity of complications (≥ grade II), the <2 weeks subgroup had the highest morbidity rate (9.2 %) (Table 4). In the multivariate analysis, the ORs for the development of postoperative complications in the subgroup whose smoking cessation period was <2 weeks before the surgery was 3.35 (95 % CI 1.92–5.83) compared with the nonsmoker group, and the <2 weeks subgroup also had a significantly higher risk of each type of complication except for bleeding. The other subgroups, in which the smoking cessation period was longer than 2 weeks, showed no statistically significant differences in postoperative complication risk compared to the nonsmoker group (Table 5).

Three-year recurrence-free survival and overall survival

The median follow-up period was 39 months, and 49 patients died (3.7 %) during this period. Forty patients (3.0 %) died of gastric cancer recurrence and nine patients (0.7 %) died of postoperative acute myocardial infarction or other underlying diseases.

The 3-year RFS was 91.0 % in the nonsmoker group and 91.5 % in the smoker group (P = 0.884), and the 3-year OS of the nonsmoker group was 96.7 and that of the smoker group was 95.5 % (P = 0.285), which were not significantly different.

Discussion

There have been many studies that have suggested that smoking increases the incidence of postoperative complications, and that such complications could be reduced by smoking cessation prior to surgery. In fact, there has been a lack of research on the optimal period of smoking cessation required to reduce postoperative complications, and it is therefore difficult to recommend a clear-cut period of smoking cessation to patients. Some studies have found that 3–8 weeks of smoking cessation before surgery reduced postoperative complications [21–24], while other studies did not demonstrate this salutary effect with the shorter cessation time [25, 26].

In the present study of gastric cancer patients, postoperative complications such as wound complications, pulmonary complications, and leakage occurred more frequently in the smoker group than in the nonsmoker group, which might have influenced the prolonged hospital stay of the smoker group. Smokers also had a higher morbidity rate (≥grade II) than nonsmokers, especially those with <2 weeks of smoking cessation. Multivariate analysis according to the smoking cessation period before surgery showed that the occurrence of postoperative complications increased significantly in patients with <2 weeks of smoking cessation before surgery. It can thus be suggested that smoking cessation for more than 2 weeks before surgery helps reduce the occurrence of postoperative complications. This finding is very important for patients as well as surgeons in gastric cancer surgery, considering that we suggested the shortest period of smoking cessation before surgery of all recent results. Our results should aid actual clinical applications, because 2 weeks may be the minimum period needed to prepare for the operation, and this can provide patients with a strong motivation to stop smoking. For patients who have difficulty with smoking cessation, nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) in parallel with active counseling is thought to be helpful for achieving better results [27].

It is well known that postoperative complications are associated with both the acute toxic effects of recent smoking before surgery and the cumulative chronic toxic effects of long-term smoking [13, 15]. However, it is difficult to determine the precise smoking history of any smoker who is due to undergo surgery and to reverse its chronic effects. It appears that the acute toxic effects of smoking are important influences on postoperative complications according to our results, which indicate that patients with a brief smoking cessation history preoperatively (especially <2 weeks) have more complications. Tissue hypoxia caused by acute exposure to smoking is considered to be the most important cause of this link [28], and this explanation is supported indirectly by other studies in which supplying a high concentration of oxygen during and after surgery was found to reduce the incidence of wound complications [29, 30]. Smoking also decreases collagen synthesis and interferes with the intercellular transfer required for the synthesis of proper connective tissue, and as a result it adversely affects the wound healing process [31, 32]. In addition, both acute exposure to smoking and the accumulated chronic toxic effects of smoking may adversely affect pulmonary function, which could lead to postoperative respiratory failure or pneumonia [33].

Though the length of the period of smoking cessation that is required to reduce all these negatives before surgery is not known, it is thought that even a short period of smoking cessation before surgery can reduce the damage caused by acute exposure to smoking. There is also a report that nicotine and carbon monoxide in tobacco have relatively short half-lives, meaning that even a short period of smoking cessation over a few days is also beneficial [34, 35].

Turning our attention to prognosis in the present study, there was no significant difference in 3-year RFS and 3-year OS between the smoker group and the nonsmoker group. It is assumed that a patient’s prognosis is associated more with the stage of gastric cancer at the time of diagnosis, not with the history of smoking cessation. There is still little evidence of an association between lifestyle (e.g., alcohol and cigarette smoking) and prognosis of gastric cancer. While Smyth et al. [36] reported that smoking was associated with the survival of gastric cancer patients, a meta-analysis reported that drinking decreased survival but that there was no significant association with smoking [37]. Though our study has a relatively short follow-up period compared to other studies, the results are important given that most gastric cancer recurrences occur within 2 years [38, 39].

There are some limitations to the present study. First, assessing complications only by smoking cessation period before surgery without similarly assessing quantity of cigarettes smoked has the potential for bias. Although these data should be interpreted with caution considering that quantity of cigarettes smoked was ignored, it is suggested that all smokers benefit from smoking cessation for a period of 2 weeks or more before gastric cancer surgery, regardless of the quantity of cigarettes they smoke. Another limitation is that their smoking habits were only surveyed by questionnaires and interviews; there was no biological monitoring (e.g., expired carbon monoxide, nicotine metabolites), which is more objective. The reliance on questionnaires and interviews may have resulted in misclassification and miscalculation of the risk of complications in subgroup analysis. These limitations aside, our study does provide the first results from an investigation of the influence of length of smoking cessation period on the incidence of postoperative complications in a large number of patients who underwent curative radical gastrectomy, and the results have further significance in that the present study suggested that a shorter period of smoking cessation reduced the incidence of postoperative complications than found in other studies.

In conclusion, it is suggested that smoking cessation for a period of at least 2 weeks before gastric cancer surgery helps to reduce postoperative complications such as wound complications, pulmonary complications, and leakage. More studies should be conducted in the future on the duration and benefits of smoking cessation before surgery. It is recommended that all surgeons who perform gastric cancer surgery should actively encourage and help patients to stop smoking. This may also help to reduce the associated postoperative morbidity rate and length of hospital stay.

References

Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–917.

Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, Oh CM, Seo HG, Lee JS. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival and prevalence in 2010. Cancer Res Treat. 2013;45:1–14.

Shin A, Kim J, Park S. Gastric cancer epidemiology in Korea. J Gastric Cancer. 2011;11:135–40.

Bertuccio P, Chatenoud L, Levi F, Praud D, Ferlay J, Negri E, et al. Recent patterns in gastric cancer: a global overview. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:666–73.

Nishino Y, Inoue M, Tsuji I, Wakai K, Nagata C, Mizoue T, et al. Tobacco smoking and gastric cancer risk: an evaluation based on a systematic review of epidemiologic evidence among the Japanese population. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2006;36:800–7.

Ladeiras-Lopes R, Pereira AK, Nogueira A, Pinheiro-Torres T, Pinto I, Santos-Pereira R, et al. Smoking and gastric cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:689–701.

Koizumi Y, Tsubono Y, Nakaya N, Kuriyama S, Shibuya D, Matsuoka H, et al. Cigarette smoking and the risk of gastric cancer: a pooled analysis of two prospective studies in Japan. Int J Cancer. 2004;112:1049–55.

Ueshima H, Sekikawa A, Miura K, Turin TC, Takashima N, Kita Y, et al. Cardiovascular disease and risk factors in Asia: a selected review. Circulation. 2008;118:2702–9.

Ueshima H. Explanation for the Japanese paradox: prevention of increase in coronary heart disease and reduction in stroke. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2007;14:278–86.

Martiniuk AL, Lee CM, Lam TH, Huxley R, Suh I, Jamrozik K, et al. The fraction of ischaemic heart disease and stroke attributable to smoking in the WHO Western Pacific and South-East Asian regions. Tob Control. 2006;15:181–8.

Gonzalez CA, Lopez-Carrillo L. Helicobacter pylori, nutrition and smoking interactions: their impact in gastric carcinogenesis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:6–14.

Stein CJ, Colditz GA. Modifiable risk factors for cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:299–303.

Hawn MT, Houston TK, Campagna EJ, Graham LA, Singh J, Bishop M, et al. The attributable risk of smoking on surgical complications. Ann Surg. 2011;254:914–20.

Gajdos C, Hawn MT, Campagna EJ, Henderson WG, Singh JA, Houston T. Adverse effects of smoking on postoperative outcomes in cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:1430–8.

Khullar D, Maa J. The impact of smoking on surgical outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:418–26.

Owen D, Bicknell C, Hilton C, Lind J, Jalloh I, Owen M, et al. Preoperative smoking cessation: a questionnaire study. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61:2002–4.

Dimick JB, Chen SL, Taheri PA, Henderson WG, Khuri SF, Campbell DA Jr. Hospital costs associated with surgical complications: a report from the private-sector National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:531–7.

Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection. Am J Infect Control. 1999;27:97–132 (quiz 3–4; discussion 96).

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–13.

Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, et al. The Clavien–Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250:187–96.

Kuri M, Nakagawa M, Tanaka H, Hasuo S, Kishi Y. Determination of the duration of preoperative smoking cessation to improve wound healing after head and neck surgery. Anesthesiology. 2005;102:892–6.

Lindstrom D, Sadr Azodi O, Wladis A, Tonnesen H, Linder S, Nasell H, et al. Effects of a perioperative smoking cessation intervention on postoperative complications: a randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2008;248:739–45.

Sorensen LT. Wound healing and infection in surgery. The clinical impact of smoking and smoking cessation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Surg. 2012;147:373–83.

Møller AM, Villebro N, Pedersen T, Tønnesen H. Effect of preoperative smoking intervention on postoperative complications: a randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2002;359:114–7.

Sorensen LT, Jorgensen T. Short-term pre-operative smoking cessation intervention does not affect postoperative complications in colorectal surgery: a randomized clinical trial. Colorectal Dis. 2003;5:347–52.

Myers K, Hajek P, Hinds C, McRobbie H. Stopping smoking shortly before surgery and postoperative complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:983–9.

Mastracci TM, Carli F, Finley RJ, Muccio S, Warner DO. Effect of preoperative smoking cessation interventions on postoperative complications. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:1094–6.

Ninikoski J. Oxygen and wound healing. Clin Plast Surg. 1977;4:361–74.

Greif R, Akca O, Horn EP, Kurz A, Sessler DI. Supplemental perioperative oxygen to reduce the incidence of surgical-wound infection. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:161–7.

Belda FJ, Aguilera L, Garcia de la Asuncion J, Alberti J, Vicente R, Ferrandiz L, et al. Supplemental perioperative oxygen and the risk of surgical wound infection: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294:2035–42.

Jorgensen LN, Kallehave F, Christensen E, Siana JE, Gottrup F. Less collagen production in smokers. Surgery. 1998;123:450–5.

Wong LS, Martins-Green M. Firsthand cigarette smoke alters fibroblast migration and survival: implications for impaired healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2004;12:471–84.

Mattison S, Christensen M. The pathophysiology of emphysema: considerations for critical care nursing practice. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2006;22:329–37.

Pearce AC, Jones RM. Smoking and anesthesia: preoperative abstinence and perioperative morbidity. Anesthesiology. 1984;61:576–84.

Kambam JR, Chen LH, Hyman SA. Effect of short-term smoking halt on carboxyhemoglobin levels and P50 values. Anesth Analg. 1986;65:1186–8.

Smyth EC, Capanu M, Janjigian YY, Kelsen DK, Coit D, Strong VE, et al. Tobacco use is associated with increased recurrence and death from gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:2088–94.

Ferronha I, Bastos A, Lunet N. Prediagnosis lifestyle exposures and survival of patients with gastric cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2012;21:449–52.

Sakar B, Karagol H, Gumus M, Basaran M, Kaytan E, Argon A, et al. Timing of death from tumor recurrence after curative gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2004;27:205–9.

Choi JY, Ha TK, Kwon SJ. Clinicopathologic characteristics of gastric cancer patients according to the timing of the recurrence after curative surgery. J Gastric Cancer. 2011;11:46–54.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jung, K.H., Kim, S.M., Choi, M.G. et al. Preoperative smoking cessation can reduce postoperative complications in gastric cancer surgery. Gastric Cancer 18, 683–690 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-014-0415-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-014-0415-6