Abstract

Background

The strategy for treating extremely aged patients with gastric carcinoma is controversial. This study reviews the prognoses of patients aged 85 years and older who were diagnosed with gastric carcinoma.

Methods

One hundred seventeen patients aged 85 years and older were diagnosed as having gastric carcinoma after 1969 in our institution. After excluding those at stage IV, 36 cases underwent curative resection and 30 cases received best supportive care (BSC), which we reviewed retrospectively.

Results

Surgical methods included distal gastrectomy for 28 cases, total gastrectomy for five cases, and other procedures for three cases. Postoperatively, pneumonia developed in four cases, anastomotic leakage in two cases, and pancreatic fistula in one case. Two patients died of pneumonia within 1 month of surgery. Univariate analysis demonstrated that age, surgery, performance status, and sodium level were statistically significant prognostic factors. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that surgery was the only independent prognostic factor. When patients with a performance status of 4 were excluded, the clinical characteristics of the surgery group (n = 36) and BSC group (n = 20) were statistically identical, and the overall survival was significantly better in the surgery group (p = 0.0078).

Conclusions

Postoperative outcomes were relatively acceptable. Surgery may be feasible and beneficial even for extremely aged patients 85 years and older, except for those with a performance status of 4.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The average human life expectancy is increasing in Japan, and it already has one of the longest life expectancies in the world. As a result of this trend for longer lives, the proportion of elderly patients diagnosed with gastric carcinoma is also increasing.

Elderly people are sometimes divided up into the young old (65–74), the old old (75–84) and the oldest old (85+) [1]. In Japan, many of the oldest old persons are older than the average human life expectancy. Although gastric surgery for young old and old old patients has become more common, surgeons often hesitate to perform operations on the oldest old patients. As many of the oldest old patients have comorbidities, the risk of surgery is often high. In some cases, gastric carcinoma may not affect life expectancy because of the patient is already of an advanced age. Thus, the strategy for treating the oldest old patients with gastric carcinomas is controversial. In order to gain a picture of this strategy, we reviewed the prognoses of patients aged 85 years and older who were diagnosed with gastric carcinoma at our institute.

Patients and methods

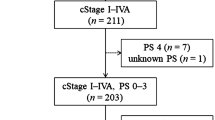

From 1969 to 2008, the number of patients diagnosed with gastric carcinoma by histopathological examination in our institution was 5,213. Among them, 117 patients (2.24%) were aged 85 years or older; 64 were female and 53 were male. Ninety patients were between 85 and 89 years old and 27 patients were between 90 and 97 years old. Twenty-three patients received endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), 36 patients received curative resection, 12 patients received noncurative resection or bypass surgery, 30 patients who were not at clinical stage IV according to the 14th edition of the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma (JCGC) [2] received best supportive care (BSC) without surgery, and 16 patients at stage IV or at an unknown stage received BSC without surgery. We reviewed the prognoses of 36 patients who underwent curative resection and 30 patients who were not at stage IV and received BSC without surgery. Curative resection means R0 in JCGC; in other words, neither a microscopic nor a macroscopic residual tumor is left.

Curative resection was performed on 21 females and 15 males. Surgical treatment included distal gastrectomy (DG) with D0 lymph node dissection for three patients, D1 for 19 patients, D2 for five patients, total gastrectomy (TG) with D1 for four patients, D2 for one patient, laparoscopy-assisted DG with D1 for one patient, proximal gastrectomy for one patient, partial gastrectomy for one patient, and pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) for one patient.

BSC without surgery was selected for 20 females and 10 males who were not at stage IV. The selection was made on the basis of comorbidities by physicians and/or surgeons in 11 cases, by the family in 11 cases, and by the patient in 8 cases.

The POSSUM scoring system [3] was used to assess perioperative surgical risks. Physiological POSSUM scores were calculated based on age, cardiac signs, chest radiograph, respiratory history, systolic blood pressure, pulse rate, Glasgow coma scale, hemoglobin, white cell count, plasma urea, plasma sodium, plasma potassium, and electrocardiogram. Each item was scored from 1 (normal) to 8 (abnormal). The maximum physiological score was 88 and the minimum was 12. High physiological scores mean a higher risk for surgery.

The log-rank test and Cox’s proportional hazards model were used to perform univariate and multivariate survival analyses. The values for data were expressed as medians and ranges. Mann–Whitney U and chi-square tests with and without Yates’ correction were used to compare differences between groups. Survivals were shown on Kaplan–Meier curves and compared by a log-rank test. A p value of <0.05 was defined as statistically significant, and all analyses were carried out using StatView (version 5.0 for Macintosh; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

In terms of postoperative complications, pneumonia was observed in three cases (three 85 year old males who underwent DG with D1, DG with D2, and TG with D1), other respiratory failure in one case (an 86 year old female who underwent TG with D1), anastomotic leakage in two cases (an 87 year old male who underwent DG with D2 and an 89 year old male who underwent TG with D1), and pancreatic fistula in one case (an 85 year old female who underwent PD). Two patients died from pneumonia on the 5th and 28th postoperative day, respectively (two 85 year old males who underwent DG with D1 and DG with D2). The median follow-up period for the 14 living patients was 40 months, and 22 patients (61%) died during follow-up. Causes of death included gastric carcinoma in four cases (18%), pneumonia in seven cases (32%), cardiac disease in one case (5%), other carcinomas in two cases, pulmonary embolism in one case, and the cause was unknown in seven cases.

The median follow-up period for the 7 living patients receiving BSC who were not at stage IV was 16 months, and 23 patients (77%) died during follow-up. The causes of death included gastric carcinoma in 12 cases (52%), pneumonia in three cases (13%), cardiac disease in four cases (17%), other carcinoma in one case, and the cause was unknown in three cases.

The results of univariate and multivariate analyses of the overall survival of patients with curative resection and BSC who were not at stage IV are shown in Table 1. Variables included sex, age, clinical or pathological stage according to JCGC, surgery, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status [4], and each item of the POSSUM physiological score. Univariate analyses revealed that age, surgery, performance status, and sodium were statistically significant prognostic factors. A multivariate analysis demonstrated that surgery was the only independent prognostic factor.

Performance status was a significant prognostic factor and surgeons and physicians intuitively judged operability based on performance status. In this oldest old series, no patients with a performance status of 4 received surgery. Excluding the nine BSC patients with a performance status of 4 and one BSC patient with an unknown performance status, the clinical characteristics of the OP group (n = 36) who received curative resection and the BSC group (n = 20) with performance statuses of 0–3 who were not at stage IV and did not undergo surgery were compared (Table 2). There were no significant differences for each item, including age, performance status and sodium levels. The overall survivals of the OP and BSC groups are shown on the Kaplan–Meier curves in Fig. 1. Three-year survival rates were 47.9 and 20.0%, and 5 year survival rates were 32.2 and 0%, respectively. There was a significant difference in survival rate between the two groups (p = 0.0078).

Discussion

The average human life span is increasing in Japan (it was 86.44 years old for females and 79.59 for males in 2009 [5]). The proportion of the population aged 85 years and older in Japan is as high as 2.9% [6]. Our institution is located in Kure, a suburb of Hiroshima, and it provides services to underpopulated islands. The proportion of the population aged 85 years and older in Kure City reached 4.3% in 2010 [7].

For gastric cancer stages IA–IIIC, the standard therapy is undoubtedly curative surgical resection, except in early cases, which may warrant endoscopic resection. However, the average life expectancy of the oldest old patients is rather short (i.e., 8.13 years for an 85 year old female and 6.09 years for a male of the same age), as reported in 2006 [8]. Considering this rather short life expectancy and the increased risk for surgery for the oldest old patients who present comorbidities, there has been controversy over whether surgical resection is the best way to care for these patients.

Findings indicated acceptable incidences of surgical complications for the oldest old patients. Especially in patients over 89 years old, no surgical complication was observed. This is due to the advanced perioperative management that occurs in fields such as anesthesiology, intensive care, surgical techniques and devices. Additionally, we have attempted to perform less invasive surgery. Dissection of the lymph node tended to be performed relatively infrequently in the current series. Katai et al. [9] reported that total gastrectomy and extended nodal dissection were both associated with high operation-related death rates in patients with preoperative morbidities. Indeed, the rate of surgical complications was higher in the TG cases in the current study.

Notably, 32% of the patients died of pneumonia following curative resection. The causes of death in Japan in 2002 were listed as follows: malignant neoplasm 20.2%, cardiac disease 18.7%, stroke 17.1%, and pneumonia 14.0% for individuals 85–89 years old; cardiac disease 19.7%, stroke 16.7%, pneumonia 16.5%, and malignant neoplasm 12.1% for individuals 90+ years old [10]. Patients were more likely to die of pneumonia than natural causes postoperatively. In the current series, two died within 1 month after surgery, and the remaining five cases died about 1 year more after the surgery. Pain, recumbency, decreased power of the respiratory muscles, and suppression of the cough reflux may lead to early death from pneumonia. Concerning the late phase, gastrectomy may trigger gastroesophageal reflux and thus cause pneumonia in the oldest old patients.

Generally, the most important factor affecting survival was the stage of gastric cancer. In the current study, however, univariate analyses revealed that the stage of cancer was not a statistically significant indicator of overall survival of the oldest old patients. Age, surgery, performance status, and sodium were significant factors. Physiological values, except sodium, were not significant indicators of survival. Based on a multivariate analysis, surgery was the only independent prognostic factor. The overall survival curve also indicated that surgery significantly improved the prognosis of the oldest old patients, except for those with a performance status of 4. This may mean that surgery should not be rejected straight away for patients of very advanced age. Performance status and general condition may weigh more in the indication for surgery.

As this was a one-institution, small-sized retrospective study, we could not draw any definitive conclusions. A multicenter, large-sized study is recommended for future investigations. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are preferable in order to establish a reliable conclusion, but it would be rather difficult to invite the oldest old patients to join RCT and assign them to surgery or BSC, because many of them decide on their treatment based on their principles or those of their families.

Dementia is an important problem for old patients, and it often worsens performance status. In the current series, 78% of the patients with a performance status of 4 exhibited disorientation and/or confusion due to dementia. When the subjects were limited to a performance status of 0–3 (n = 56), the number of patients with disorientation and/or confusion (Glasgow coma scale ≤14) was only five. Two of them selected BSC because their families rejected surgery, and the other three underwent surgery. In this institution, the surgeons did not reject surgery due to dementia in cases with a performance status of 0–3.

When reviewing the literature, we noted that some articles discussed the surgical outcomes for patients who were over 80 years old; however, few of these works discussed patients over 85 years old. Ishigami et al. [11] stated that survival in patients aged 85 years and older was not affected by surgical resection. However, Ishigami et al.’s work was completed over a decade ago, and perioperative management and the clinical features of patients over 85 have changed since then, making surgery more reliable.

More recent work has reported the feasibility of laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy (LAG) in older patients. Yamada et al. [12] revealed that LAG could be safely performed in patients who were older than 80 years with complication rates and operational outcomes that were similar to those seen for patients aged 70–79 years. We performed only one LAG in the current series. As the number of LAG cases increases dramatically with early gastric cancer treatment in Japan, we believe that LAG should be adopted for even the oldest old patients. This less invasive approach may result in a lower incidence of postoperative pneumonia.

In summary, we reviewed the prognoses of patients aged 85 years and older who were diagnosed with gastric carcinoma in our institution. Surgical resection may be feasible and beneficial even for such old patients if their performance status is as good as 0–3. As this was a one-institution, small-sized retrospective study, a multicenter, large-sized study is recommended for future investigations.

References

Crews DE, Zavotka S. Aging, disability, and frailty: implications for universal design. J Physiol Anthropol. 2006;25:113–8.

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma. 14th ed. Tokyo: Kanehara; 2010. p. 5–17 (in Japanese).

Copeland GP, Jones D, Walters M. POSSUM: a scoring system for surgical audit. Br J Surg. 1991;78:355–60.

Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, McFadden ET, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649–55.

Statistics and Information Department, Minister’s Secretariat, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japanese Government. Abridged life tables for Japan 2009. I. Life expectancies at specified ages. Tokyo: Statistics and Information Department, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; 2010. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-hw/lifetb09/1.html. Accessed 27 July 2010.

National Statistics Center. Population estimates by age (5-year group) and sex. Seifu tokeino sogo madoguchi. Tokyo: National Statistics Center; 2010. http://www.e-stat.go.jp/SG1/estat/List.do?lid=000001060069. Accessed 21 June 2010.

City of Kure. Population by age and sex. Kure: City of Kure; 2010. http://www.city.kure.lg.jp/~statics/people.html. Accessed 21 June 2010.

Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Statistical Bureau, Director-General for Policy Planning (Statistical Standards) and Statistical Research and Training Institute. Trends of average expectation of life by age. Tokyo: Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications; 2010. http://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/nenkan/backdata/1431-02.htm. Accessed 21 June 2010.

Katai H, Sasako M, Sano T, Fukagawa T. Gastric cancer surgery in the elderly without operative mortality. Surg Oncol. 2004;13:235–8.

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The cause of death by age. Annual health, labour and welfare report. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; 2004. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/wp/hakusyo/kousei/04/dl/0a.pdf. Accessed 21 June 2010.

Ishigami S, Natsugoe S, Hokita S, Iwashige H, Saihara T, Tokushige M, et al. Strategy of gastric cancer in patients 85 years old and older. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:2091–5.

Yamada H, Kojima K, Inokuchi M, Kawano T, Sugihara K. Laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy in patients older than 80. J Surg Res. 2010;161:259–63.

Acknowledgments

These authors are grateful for the prognostic investigations of Ms. Fumiko Matsufuru, Ms. Mika Ozaki, Ms. Keiko Kawamoto, Ms. Megumi Kubo and Ms. Miwako Fujikawa, the Health Information Managers in the Department of Medical Information at the National Hospital Organization Kure Medical Center/Chugoku Cancer Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Endo, S., Yoshikawa, Y., Hatanaka, N. et al. Treatment for gastric carcinoma in the oldest old patients. Gastric Cancer 14, 139–143 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-011-0022-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-011-0022-8