Abstract

Although several internal and external factors may influence environmental non-governmental organizations’ (ENGOs) action sets and networking behaviors, their values and priorities deserve special attention. Existing research highlights the importance of mobilizing resources and utilizing political opportunities in environmental advocacy; however, there is relative silence regarding the impact of how ENGOs cognitively position themselves in a contested field. Through a quantitative analysis of survey data from 117 local ENGOs in the Aegean Region of Turkey, we examine whether and how organizational identity, scope of environmental issues, and core environmental purpose (transactional or informational) as three cognitive filters play a role in shaping grassroots ENGO activities and relationships with diverse actors. A set of regression models indicates that claiming an activist identity, pursuing a higher number of environmental issues, and having a confrontational goal significantly influences local ENGOs’ strategic actions and the type and intensity of their external ties. These findings contribute to the discussions around resource mobilization theory and the political opportunity structure framework by highlighting the importance of intangible, less visible, ideological dimensions, and of cognitive framing in mobilizing for environmental causes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Environmental non-governmental organizations (ENGOs) are viewed to voice society’s environmental concerns, spread environmental awareness, and challenge harmful state and corporate policies (Betsill and Corell 2001; Murphy-Gregory 2018). They can influence policy outcomes by mobilizing public pressure (Shwom and Bruce 2018). However, most evidence for these impacts belongs to large ENGOs at national and international scales. Local ENGOs continue to struggle because of various problems, including a lack of budget, limited human resources, and a lack of meaningful participation and recognition (Bernauer and Betzold 2012; Berny and Rootes 2018).

Although existing research highlights the importance of mobilizing resources and utilizing political opportunities, it is limited in its impact on how local ENGOs cognitively position themselves while dealing with local environmental issues and how this positioning is manifested in strategic action choices and collaborations with diverse actors at the regional level (Schoon et al. 2017). By revisiting the assumptions of resource mobilization theory (RMT) and the political opportunity structure (POS) framework, and utilizing the concept of “cognitive filters” (Carmin and Balser 2002; Hamilton-Webb et al. 2019), this article aims to understand what types of actions and networking behaviors local ENGOs in a developing country engage in, and why. Cognitive filters are described as mental schemas that lead to specific meaning constructions and interpretations of what is essential, acceptable, and legitimate, and offer the foundation for particular organizational decisions (Carmin and Balser 2002). Accordingly, this study investigates the impact of three cognitive filters—organizational identity, issue scope, and organizational orientation—on ENGOs’ choices of strategic actions and ties with local authorities, the national government, private sector, and other environmental groups. While examining these effects, we also consider what roles other essential organizational attributes (e.g., formalization, age, size, financial and human resources, and location) might play. To this end, we collected survey data from 117 local grassroots ENGOs and tested six hypotheses using a set of regression analyses.

This study makes several significant contributions in multiple ways. Firstly, most research about institutionalized ENGOs is conducted in developed country circumstances (Hadden and Bush 2021) or on large institutionalized ENGOs as single case studies (Kadirbeyoğlu et al. 2017; Paker et al. 2013). This article focuses on the behaviors of a large number of grassroots environmental organizations in a developing country, Turkey, comparing them based on a set of attributes and behaviors. Second, most research on ENGOs takes samples either from the national (Berny and Rootes 2018) or international level (Bernauer and Betzold 2012; Betsill and Corell 2001), whereas this study analyzes environmental organizations at the regional level by unveiling their diverse actions and stakeholder relationships (Feliciano and Sobenes 2022; Schoon et al. 2017). Hence, this study constitutes one of the few examples in the literature that scrutinizes the impact of crucial organizational characteristics (organizational identity, issue scope, and organizational goals) on both advocacy tactics and relationships of ENGOs, based on how they cognitively locate themselves in the contested field of regional environmental problems.

This article first defines ENGOs and discusses the state of ENGOs in developing countries and in Turkey. Next, in the “Theoretical background” section, we lay out the cognitive framing (filters) perspective on the available ideas around resource mobilization and political opportunity structure frameworks. Subsequently, the study’s hypotheses and research methodology are presented. These are followed by the data analysis, results, and a discussion of these results.

Environmental non-governmental organizations

ENGOs remain a central topic in several fields, including politics, political ecology, sociology, economics, and organizational studies. Based on the classic conceptualization of social movement organizations by McCarthy and Zald (1977), an ENGO can be defined as a complex informal or formal organization that identifies preferences within the environmental movement and attempts to implement specific environmental goals. As ENGOs coordinate resources to make their opinions explicit, they are central to all efforts to address ecological challenges.

ENGOs are diverse, fluid, and complex. Their activities range from local to global (Saunders 2007). ENGOs may take the form of mass advocacy groups or formally institutionalized organizations. They may also use various strategies and tactics. These choices are not mutually exclusive, as ENGOs might choose various forms and tactics over time and place (Rootes 2003; Shwom and Bruce 2018). However, having diverse tactics and organizational choices does not mean that ENGOs use these equally. These choices follow their goals, identities, and resources (Dalton et al. 2003).

Environmental activism in developing countries

Globalization has significantly increased the environmental degradation in developing countries (Onwachukwu et al. 2021; Tran 2020). Due to deregulation and trade liberalization policies, brown industries have shifted their production to the Global South, in other words, to developing countries, where environmental rules are laxer and labor costs are cheaper. While foreign investments in extractive and brown sectors are mostly celebrated by the leaders of developing countries due to their contribution to the growth of these countries, they have deepened and widened both labor exploitation and environmental degradation in these countries and fueled a consumption-based economy in the Global North. This has led to environmental struggles based on global social justice demands and indigenous rights in the Global South. In Martinez-Alier’s terms, these movements in developing countries can be called “the environmentalism of the poor,” and they are divergent from “the environmentalism of the rich,” which are mostly widespread in the Global North and predominantly concerned with the protection of wildlife and biodiversity (Martinez-Alier 2002).

ENGOs in Turkey

Similarly, as a developing country from the Global South, Turkey’s economic history is replete with environmental conflicts (Adaman et al. 2017; İnal and Turhan 2019). They generally originate from the top-down implementation of policy decisions taken with the discourse of civilizing a “backward” population, socio-ecological injustices, and democracy deficits. Especially after the mid-1980s, with the effect of rising neoliberalism, the number of both local environmental resistance movements and environmental organizations in an institutionalized form rose. Bergama and Artvin-Cerattepe environmental movements are among the significant environmental struggles that started in these years (Gönenç, 2021; Özen and Doğu, 2020). After the Adalet ve Kalkinma Partisi (AKP) came to power in 2002, environmental justice movements have sped up and spread around the country rapidly as a response to destructive neoliberal policies to defend rural and urban life spaces. Examples include resistance movements against hydropower, mining, shipbreaking, wind turbines, geothermal and nuclear energy, and large construction projects such as the Istanbul Canal Project and the third airport in Istanbul.

In recent investigations, ENGOs have been increasingly perceived as critical mobilizing structures that enhance fundraising, staffing, political influence, outreach, and assembly to attain their objectives (RMT, Walker and Martin 2019). Another related reorientation in current research is the appreciation of ENGOs’ diverse connections, collaborations, and contestations, with several actors within a strategic action field (Fligstein and McAdam 2012), drawing attention to political opportunity structures (POS, Tarrow 2008). We briefly outline these two perspectives below. Second, we propose the cognitive filters framework as a strong conceptual tool and explain how it can enhance our understanding of local ENGOs’ strategic actions and relationships beyond what has been argued regarding RMT and POS.

Theoretical background

Resource mobilization theory (RMT)

Several theoretical perspectives have been adopted to support the growth and strengthening of social movements. Among these, RMT requires special attention. It places a social movement’s resources at the epicenter of the analysis. The more resources an organization has, the more active and effective it will be (McCarthy and Zald 1977; Walker and Martin 2019). The amount and type of resources influence the selection of strategic actions and the availability and choice of specific relationships (Carmin and Balser 2002). In addition, resources are not only material; experiences, values, philosophy, framing capacity, and human resources also increase the power of an organization to mobilize (Pacheco-Vega and Murdie 2020). RMT sees ENGOs as rational entities which expand their action portfolios as their resources grow. Researchers have generally investigated two topics within RMT: competition and coalition building among NGOs in a field. NGOs often compete for scarce resources. On the other hand, initiating contacts and developing alliances enable them to exchange human skills, materials, and other resources (Walker and Martin 2019).

According to the RMT, the more resources an organization possesses, the more impactful it becomes (McCarthy and Zald 1977). Capacity building is crucial for engaging in strategic activities including communication and networking, which in turn supports effective environmental governance (Carmin 2010). Local ENGOs rarely possess sufficient capacity and resources to influence national or international environmental policymaking. In general, international ENGOs have significantly higher incomes than their local counterparts do.

Political opportunity structure (POS)

According to the POS framework, the institutional context of an organization influences its behaviors, choices, and actions (Meyer and Staggenborg 1996). This framework focuses on how a movement’s emergence, configuration, and success depend on the broader political environment (Walker and Martin 2019). “Political opportunity” constitutes the extent to which social movements have access to elites and other essential actors, who are influential on decisions or decision-making processes (Tarrow 2008; van der Heijden 1997). Hence, POS encompasses the dimensions in the environment that shape expectations and, in turn, bring incentives to groups for collaborating (van der Heijden 1997; Carmin and Balser 2002).

It is essential to acknowledge that the external environment is composed of different segments, each with its attributes and influences on the focal organization. Moreover, each environmental segment is dynamic, undergoing constant cycles of disruption and reconstruction (Walker and Martin 2019). While external forces and institutions constrain ENGOs, ENGOs also influence, shift, and reconstruct these forces through collective action (Dellmuth and Bloodgood 2019). Thus, an ongoing interaction exists between ENGOs and the political, economic, and social environments in which they are located.

Cognitive filters framework

Although they provide useful lenses for analyzing ENGOs, both RMT and POS have considerable shortcomings. A significant claim in RMT is that structural factors and material resources should be appropriate for ENGOs to follow certain agendas, mostly ignoring how these resources interact with the core values and beliefs of the organizational members or how particular mindsets within ENGOs lead to diverse assessments of the available resources. Similarly, POS emphasizes relatively stable and strong conditions that are supposed to affect environmental groups in the same way. However, even in the same political and social context, ENGOs’ diverse values, priorities, and interpretations would make them behave differently.

However, the extent to which ENGOs effectively achieve their objectives remains controversial. Some scholars imply that certain combinations of strategic choices and political frameworks create diverse routes for ENGOs, and that their ability to improve environmental causes is determined by this complexity (Kadirbeyoğlu et al. 2017; Hess and Satcher 2019). In response to these shortcomings, a renewed perspective suggests that in addition to the available resources and external conditions, ENGOs make decisions based on their core values, assumptions, and goals (Zald 2000). The sense-making view asserts that organizations comprehend the socio-political and economic environments as well as possible types and uses of resources through different “cognitive filters”; the schemas that afford a particular, subjective opinion of situations (Weick 1995). These cognitive filters lead to specific meaning constructions and interpretations of what is essential, acceptable, and legitimate, which offers the foundation for particular decisions and actions (Carmin and Balser 2002). Cognitive frames (or filters) are “mental schemas that individuals impose on the information environment to give it meaning” (Walsh 1995, p. 281). They serve as interpretative lenses capable of directing the perceptions of managers and members of organizations in the environment in which they create perceptions and take action. Hence, such mental screens shape organizations’ understanding of what actions are acceptable and effective, and what opportunities and threats are available and critical in the environment. The cognitive filters concept also resonates with the general framing perspective proposed by Snow and Benford (1988). Framing constitutes identifying a problem and attributing specific sources to this problem (Benford and Snow 2000). The ideological positions and consequent attributions “inspire and legitimate the activities and campaigns of a social movement organization” (Benford and Snow 2000, p. 614).

Carmin and Balser (2002) provided an extensive discussion and analysis of the possible cognitive filters of environmental movement organizations. They identified four cognitive filters used by ENGOs in sensemaking: core values and beliefs, environmental philosophy, political ideology, and experience. According to Hamilton-Webb et al. (2019), such filters help ENGO members assess whether a particular environmental topic or situation is relevant and severe, informing them of different responses. In the form of discourses and narratives, these filters provide a shared understanding of environmental issues, which will affect the resulting policies, decisions, and behaviors (Ritter and Thaler 2022).

A more recent and comprehensive perspective on cognitive filters has been offered by Raffaelli et al. (2019), who emphasized cognitive frame flexibility and distinguished among three cognitive filters: organizational identity, field of reference (issue scope), and organizational orientation. These three filters guide organizational representatives in developing and maintaining a certain lens when evaluating strategy and action alternatives. In this study, we applied their conceptualization to understand how ENGOs make decisions about their action repertoires and partnerships.

Organizational identity filter

Identity building is an essential component of social movements and advocacy organizations. Their emergence and survival depend on a collective sense of purpose, member identification, and mutual recognition (Polletta and Jasper 2001). To be distinguished from other groups and recognized by distinctive qualities, a collective identity is defined. It unites individuals around shared concerns, gives them a sense of meaning, and makes them engage in specific collective actions (Saunders 2008). Based on the study by Raffaelli et al. (2019), there might be a tight or loose coupling between the organizational members’ conceptualization of “who we are” and the core activities of the organization, or “what we do.” Thus, the interpretive closeness or distance between the “collectively agreed upon a set of central, distinctive, and enduring characteristics” of an organization and the belief about what actions should be prioritized matters.

Field of reference filter

Organizational representatives’ cognitive frames are filtered by how they conceptualize the boundaries of their field of action. How they scan their field, particularly whether they apply a broad or narrow understanding of the map of possible issues to be considered, affects the organization’s positioning in this map and how they relate to other organizations in the same field (Gavetti and Levinthal 2000). Organizations that choose to associate themselves with a wider issue map may exploit larger opportunities and develop a more extensive set of activities, whereas those who locate themselves in a narrower landscape of issues may become limited in their actions (Raffaelli et al. 2019). The implications of the field of reference are noticeable when organizational representatives favor or adopt decisions that are consistent and aligned with the scope of the needs, concerns, and services prioritized (Porac and Thomas 1990).

Organizational orientation filter

Raffaelli et al. (2019) argued that an organization’s goals and capabilities can be developed in such a way that they are oriented towards either consistency or coexistence. Co-existence orientation (transformational goals) refers to an organizational cognitive frame that embraces an innovative, change-based agenda by recognizing and grasping a stance that contradicts the existing traditional institutional order (Smith and Tushman 2005). It permits organizations to explore new ways and make a difference beyond what is already available. In contrast, a consistency orientation (informational goals) privileges uniformity or similarity to existing norms, knowledge, and capabilities. It encourages organizations to take a position and act according to conventional wisdom and institutional arrangements.

Study hypotheses

By combining the arguments on the RMT, POS, and cognitive filter frameworks, we developed an integrated conceptual model. Figure 1 outlines how our theoretical discussion fits the available knowledge in environmental advocacy research and the specific predictions made in this study to advance this research. Specifically, using Raffaelli et al. (2019) conceptualization of three cognitive filters, we developed six hypotheses and explained how each filter affects the local ENGOs’ choice of strategic actions and ties in the Aegean Region. Below, we provide hypotheses to clarify each of these connections.

Organizational identity filter: activist identity

ENGOs may claim different collective identities. Different categorizations and typologies have captured this diversity of core beliefs and values in the literature (e.g., Diani and Donati 1999; Alcock 2008). Two major types of ENGOs can be distinguished: one aims to initiate change within established institutions, and the other assumes a more confrontational stance regarding these institutions and the actors within them (Alcock 2008). In collective activism, injustice frames, shared grievances, and legacy of resistance are incorporated into existing social identities (Gamson et al. 1982; Horowitz 2017). Confrontation with opponents’ claims support affirmation of activist identity and push the collective to protest and challenge (Einwohner 2002), coinciding with Bernstein and Olsen’s (2009) notion of “identity for critique” that involves confronting the values, categories, and practices of the dominant culture, as opposed to “identity for education,” which capitalizes on uncontroversial themes. Hence, activist identity can be described as a “system-challenger” with a frame of change rather than a volunteer identity showing a more “system-fitting” pattern with a frame of charity and cohesion (Zlobina et al. 2021).

A meaningful relationship also exists between an ENGO’s identity and its strategic actions (Dreiling and Wolf 2001; Diani 2007; Saunders 2008). ENGOs who accept the established political structure as given and seek integration into it are more likely to engage in activities such as convincing, lobbying, and raising awareness. By contrast, ENGOs with a stronger activist identity position challenge the government and other power holders and intervene in the ongoing structures of their environmental struggles (Zchout and Tal 2017).

Collectives who claim to be activists use boundaries to define themselves as challenger groups, determine their target for change, and differentiate themselves from other groups (Heaney and Rojas 2014). Activist identity motivates an organization to apply the injustice frames to their actions (Horowitz 2017) and stimulates political activity in the form of collective noninstitutionalized actions aimed at building new social structures (van Stekelenburg et al. 2016). However, it is uncertain whether these claims are strong enough to shape an ENGO’s action repertoire. On many occasions, action deliveries do not follow rhetorical efforts (Sillince and Brown 2009). Such a fit can be especially challenging for local grassroots ENGOs, who typically lack the necessary means to mobilize confrontational actions. Hence, it is essential to ask whether drawing on symbolic boundaries of activism lends itself more to unconventional activities (direct interference) expected from this identity position for local ENGOs. Accordingly, we propose the following hypotheses:

-

Hypothesis 1: Local ENGOs claiming an activist identity will engage in a higher level of strategic actions than those without an activist identity.

Various studies have focused on the existence, intensity, and types of relationships that ENGOs have with diverse actors (Dalton et al. 2003; Diani and Rambaldo 2007; Saunders 2007). The intensity of such linkages and partnerships might change considerably based on key ENGO characteristics, especially the core values of the organization (Saunders 2007; 2008). Unlike those with strong activist identity deployment, ENGOs with less emphasis on activism work to stimulate change within established government institutions rather than confronting these institutions. They engage in the politics of partnership rather than the politics of blame (Winston 2002; Richards and Heard 2005). Many ENGOs build partnerships with the private sector, also called green business alliances, to ensure access to several resources (Alcock 2008). Likewise, some ENGOs engage in initiatives to build capacity and provide services that are complementary to the state rather than advocacy. For instance, Gronow and Yla-Anttila (2019) show that Finnish ENGOs that expect support from and access to the state articulate less ambitious goals and actions; they recede strong views to secure funding and political access. ENGOs may also be eager to build ties with local authorities to promote local discretion on environmental issues and implement decentralization as a “legitimate” form of governing (Alcock 2008).

By contrast, ENGOs with an activist identity will be hesitant to develop close relationships with state authorities and the private sector. In their eyes, these actors typically bear the highest responsibility for the existing environmental damage and ecological destruction. To create change, they intend to confront these actors and maintain their autonomous status to minimize the risk of being controlled or constrained in their advocacy efforts (Zchout and Tal 2017). Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

-

Hypothesis 2a: Local ENGOs with an activist identity will build stronger ties with other ENGOs than those without an activist identity.

-

Hypothesis 2b: Local ENGOs with an activist identity have a lower probability of building ties to local administrations, the national government, and the private sector than those without an activist identity.

Field of reference filter: issue scope

Environmental organizations typically deal with a broad portfolio of environmental concerns, depending on the increasing number of ecological problems. However, they often need to choose and prioritize only a certain number of these issues (Richards and Heard 2005). How ENGOs select issues and the extent to which these environmental topics vary shape their advocacy strategies and action patterns (Diani and Pilati 2011; Kadirbeyoğlu et al. 2017). It has been suggested that the visibility and impact of NGOs improve when complex advocacy issues are dealt with through distinctive approaches (Richards and Heard 2005). A higher heterogeneity of issues necessitates taking bolder steps and performing more radical and aggressive actions than allocating resources to similar topics (Carmin and Balser 2002).

Likewise, diverse environmental issues bring different opportunities and threats to environmental organizations. To pursue these opportunities simultaneously, the focal ENGO must have a broader and more substantial impact. The higher the diversity of the issues at hand, the higher the level of confrontational actions that a local ENGO will use. By contrast, focusing on fewer issues or considerable overlap among the chosen ones will not require ENGOs to engage in high-intensity actions. They will confine themselves to more conventional and compromising actions (e.g., lobbying, public awareness, meetings with officials) rather than contentious ones (e.g., boycotting, suing, protesting). Thus, we propose that:

-

Hypothesis 3: Local ENGOs concerned with a larger issue scope will engage in a higher level of strategic actions than those with a narrower issue scope.

The scope of the issues that an ENGO works on will also influence its relations with other actors. Being concerned with multiple environmental topics concurrently requires more extensive mobilization, bringing several environmental groups together. Such coalitions would be more effective in developing the necessary expertise and creating a complementary impact when pursuing a larger issue agenda (Diani and Pilati 2011). Moreover, the burden of working on several subjects will decrease for each network member (Heaney and Rojas 2014). Being deprived of extensive financing, local ENGOs need such regional advocacy coalitions more than national, large-scale ones.

However, bringing state agencies and companies into these coalitions may not be preferable. While campaigning for multiple environmental issues, ENGOs must engage in several activities, and the number of potentially hostile encounters with state authorities and businesses is increasing (Richards and Heard 2005). Thus, a more profound commitment to multiple topics makes ENGOs hesitant or unable to build close relationships with them. Therefore:

-

Hypothesis 4a: Local ENGOs occupied with a larger issue scope will build stronger ties with other ENGOs than those occupied with a narrower issue scope.

-

Hypothesis 4b: Local ENGOs occupied with a larger issue scope have a higher probability of building ties to local administrations, the national government, and the private sector than those occupied with a narrower issue scope.

Organizational orientation filter: transformational vs. informational goal

Although all ENGOs share a common concern for the environment, their goals and strategic orientations may differ. Dreiling and Wolf (2001) suggested that the core environmental goal is an essential factor to consider when exploring ENGOs’ cognitive and interpretive processes. Some ENGOs might have more conflict-based strategies, aiming to challenge and transform existing relationships and models that damage the environment so that alternative structures can be created (Zchout and Tal 2017; Andrews and Edwards 2005). While ENGOs with a transformational goal are more likely to act aggressively using various methods to challenge the status quo, ENGOs that do not pursue a transformational goal but follow the objective of raising environmental awareness and spreading knowledge will adopt more conventional actions and avoid confrontation as much as possible. Hence, we suggest the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 5: Local ENGOs with a transformational goal will engage in a higher level of strategic actions than local ENGOs with an informational goal.

In line with the above arguments, ENGOs with a confrontational goal, with an orientation towards challenging existing political-economic structures and policies, would have a higher tendency to build strong environmental networks with other ENGOs (Dalton et al. 2003; Saunders 2007). It is likely that when a local ENGO’s primary motivation is systemic alteration, this type of coalition building will be necessary, as a single organization’s transformative capacity is limited. Meanwhile, ENGOs are more likely to oppose policymakers and industry representatives. In contrast, we might expect that an ENGO that prioritizes informational goals might have closer relationships with government and private sector actors, as the probability of hostile confrontations with these parties will be less likely. Hence, we propose the following hypotheses:

-

Hypothesis 6a: Local ENGOs with a transformational goal will build stronger ties with other ENGOs than will those with informational goals.

-

Hypothesis 6b: Local ENGOs with informational goals have a higher probability of building ties with local administrations, the national government, and the private sector than those with transformational goals.

Methodology

Research setting and sample

Tracing the geographical development of environmental movements is essential because such movements emerge from a locality’s specific economic and cultural conditions. We conducted a survey to test the research hypotheses. An online questionnaire was sent to all local grassroots ENGOs in the Aegean Region of Turkey, whose contact information was publicly available. The Aegean region, located in Western Turkey, constitutes a significant part of the country, where environmental problems and activism are predominant (see Fig. 2 for the map of the region). This is because, while the region is famous for its rich biodiversity, natural resources, and beautiful coastlines, various environmentally destructive projects (e.g., mines, hydroelectric and thermal power plants, and ports) are being initiated based on expected economic rents. The environmental struggle in the Akbelen forest against new lignite mining, the movement against the establishment of a cement factory in Bayır-Muğla, the struggle to clean up the nuclear wastes in Gaziemir-Izmir, the efforts to protect the olive tree fields in Urla-Çeşme against mining and energy projects, and the environmental movement against silver and gold mining on Kaz Mountain in Çanakkale are only a few of the newest ecological conflicts in the region. Among the 60 environmental conflict cases in Turkey, as profiled in the Environmental Justice Atlas (Temper et al. 2015), 19 are located in the Aegean Region as of 2022, the highest number ahead of the Marmara and Black Sea Regions. The region is relatively populated with more than 10 million residents and is a hub that connects agricultural, industrial, and tourism activities. According to DERBIS (2021), 25.1% of the associations that work on “environment, nature, and animal protection” exist in this region, indicating the significance of environmental concerns.

We collected data from several national and regional/local databases to compile an exhaustive list of all the ENGOs in the region. First, associations working on the environment in the Aegean Region were found in the Associations Information System (DERBIS) affiliated with the General Directorate of Civil Society Relations of the Ministry of Interior, which is the largest database containing non-governmental organizations operating in different fields in Turkey. Foundations working on the “environment,” “ecology,” and “water” were searched and found in the “Foundation Inquiry” section on the website of the General Directorate of Foundations. We then conducted additional scanning of social media accounts, reports, and articles to identify as many local ENGOs as possible. Based on a detailed investigation of the data collected, we excluded 65 ENGOs that were not directly involved in the environmental struggle or were not active. As a result, the final list comprised 285 ENGOs.

Data collection

To develop the questionnaire, we extensively reviewed empirical studies on social movements and environmental organizations. The draft survey form was shared with five environmental experts to ensure the clarity and appropriateness of the questions, and finalized according to the feedback received. We sent this revised online questionnaire to all the local ENGOs in the compiled list. On the introductory page of the survey and in the e-mail sent to the ENGOs, we asked that the questionnaire be filled out by the organization’s representative on behalf of the organization. After the first invitation, reminders were sent via e-mail and phone calls. The process was completed in four months, and responses from 131 ENGOs were received (46% response rate).

Regarding key respondent characteristics, 89% of the participating ENGOs were founded after the year 2000. Most of them are active in three coastal cities in the region: Izmir (45%), Muğla (35%), and Aydın (30%). Ecological life (58%), forest protection (51%), land pollution (51%), climate change (48%), protecting wildlife (44%), and air pollution (43%) are among the top issues they work on. Within the sample, the number of small environmental organizations with few financial resources and employees is high compared with the larger, more institutionalized, and professional ones. Most participating ENGOs lacked office space and sufficient technological infrastructure.

Measures

Dependent variables

Level of strategic actions

To identify ENGOs’ strategic actions, we first composed a list of nine unconventional actions by following examples in the literature (e.g., Dalton et al. 2003; Richards and Heard 2005; Zchout and Tal 2017) (Appendix 1). While conventional activities typically include consensus-oriented behaviors such as issuing press statements, organizing seminars and workshops, preparing leaflets and brochures, providing training, and meeting officials, strategic actions include direct interferences such as boycotts, protests, lawsuits, petitions, legal objections to environmental assessment reports, organizing campaigns, and making formal allegations. We asked the respondents to state the frequency with which their organization was involved in each of these strategic actions (5 = most of the time, 1 = never). A sum score ( a count variable) was calculated by adding up the items for which a respondent declared that their organization engages in this activity at least “sometimes.”

Strength of ties with other ENGOs

Following the relevant literature, we identified ties with other local and national ENGOs, local administrations, the national government, and the private sector as the most critical connections among all actors. Hence, we created specific questions to understand the depth of the relationship between the focal ENGO and each other. To measure the strength of their ties with other ENGOs, we asked the representatives to what extent their organizations collaboratively engages in certain activities (sharing knowledge and resources, introducing a bill, running media campaigns, and participating in protests) with other local and national environmental groups (Appendix 1). The four items were measured using a 5-point Likert scale (5 = most of the time, 1 = never). Cronbach’s alpha for the scale is 0.86.

Possible ties with other actors

To measure the probability of building ties with local administrations, the national government, and the private sector, we asked another set of questions specifically tailored to the nature of the relationship between ENGOs and cited actors (see Appendix 1). Each item set constitutes a range of possible relationships with the other actors. For each actor category, a merged binary measure was created and coded 1 if the ENGO was involved in at least one of the listed relationships with the actor. If they were not involved in any of the listed relationships, they were coded as 0.

Total tie strength

In addition to the above measures tailored for examining specific ties, we also checked focal ENGOs’ total tie strength. To do that, we asked the participants to state the intensity of contacts of their organization with eight different actors using a 5-point Likert scale (5 = very strong; 1 = very weak): local administration, national government, international institutions, other local and national ENGOs, other local and national NGOs, international ENGOs, private sector, and local community. We then built a mean value. Cronbach’s alpha value of the scale is 0.82.

Independent variables

Activist identity

Activism is a strong identity category for ENGOs, in which full membership provides clear signals to the relevant audience (e.g., individuals with a particular political ideology). This increases ENGO’s appeal to their eyes. Moreover, the claim (aspiration) of being an activist should be empirically separated from its manifestation. To assess ENGOs’ identity claims, we first composed a list of various self-descriptions. We asked participants whether they consider the organization a member of each category (e.g., activist, environmental protectionist, social service organization, aid agency) or not, as a binary measure (“yes,” “no”). If the representative regarded ENGO as an activist group, it was scored 1; otherwise, it was scored 0. We believe that this measurement has high construct validity, where the emphasis is on cognitive (ideological) position and aspiration rather than actual behaviors, which are often inaccurately mixed up and confounded in research.

Issue scope

We measured issue scope by calculating the total number of distinct topics that the responding ENGO deals with. To do that, we provided a list of 26 possible issues and asked the participant to state which ones their ENGO is most concerned with (“yes = 1,” “no = 0”). The list includes, but is not limited to, climate change, forests, air pollution, water pollution, wildlife, renewable energy, waste management, mining, and protecting agricultural lands. The issue scope was calculated by adding up each diverse issue that the ENGO works on. While a higher level indicates a larger scope, a lower level indicates a narrower scope. Out of all the possible issues, participants declared a minimum of one issue and a maximum of 23 issues, with an average of 7.97 issues. A list of all issues and their relative frequencies are given in Appendix 1.

Transformational vs. informational goals

Following Andrews and Edwards (2005), we divided the strategic goals of the ENGOs into two: confrontational (transformational) vs. non-confrontational (informational) goals and asked the participants whether each goal is a primary target for their ENGO or not in a binary format (“yes,” “no”). Having a transformational goal was measured by asking whether the ENGO seeks to fight against laws or practices that adversely affect the environment. Informational purpose was assessed by asking whether the ENGO pursues environmental monitoring, knowledge building, and reporting.

Control variables

We also included a set of critical organizational characteristics as control variables based on theoretical and empirical suggestions in the literature. The formalization level of ENGOs was measured based on whether they were structured in a legal form (e.g., association, foundation). A dummy variable that measured age: whether the organization was founded before or after 2010. The geographical scope was determined by asking whether the ENGO operates in a single local area or a broader range. We measured the amount of financial resources based on the availability of an annual budget of more than ten thousand Turkish Liras (TL). Finally, we controlled for whether the organization was founded in Izmir, the largest city in the region. Most of these controls will also enable us to keep the influence of tangible organizational resources constant and better indicate the direct impact of cognitive filters.

Assessment of common method bias

Common method bias poses a significant threat to research validity, which reflects artificially inflated relationships among variables resulting from the collection of all data using the same method (Baumgartner et al. 2021; Jordan and Troth 2020). Following Podsakoff et al. (2003), we addressed possible common method variance (CMV) effects via statistical controls and conducted two separate diagnostic analyses. First, the Harman’s single-factor test was conducted. The principal component analysis results showed that the total variance explained by a single factor alone was 25.36%, thus providing no indication of CMV. Second, we used marker variables following Lindell and Whitney’s (2001) suggestion. We selected two single items as marker variables, one related to the internal decision-making process of the ENGOs: “decisions can be changed based on member objections” (1 = never, 5 = always), and an external evaluation of societal impact: “social habits and lifestyles have an impact on the environment” (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The results indicated that including the marker variables led to only minimal changes in the correlation coefficients, and no difference was observed in the statistical significance of the relationships. These analyses, along with all descriptive and inferential statistics in the study, were performed using the SPSS 22 software.

Results

Descriptive statistics

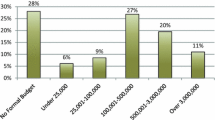

The means, standard deviations, and pairwise correlations between the variables included in this study are shown in Table 1. After removing observations with missing data, all analyses were conducted using a sample of 117 ENGOs. Among respondent organizations, 71% had a formal structure (e.g., association, foundation) instead of being organized as an informal group, initiative, platform, etc. Most were young, and 69% were founded after 2010. On average, their geographical scope is relatively narrow; 66% operate at the local level instead of the subregional or regional level. While 59% of ENGOs have an annual budget of more than ten thousand TL, only 46% have 50 or more members. These descriptive statistics imply the significant inadequacies of local ENGOs regarding capacity, resources, and experience.

The means, standard deviations, and pairwise correlations between the variables included in this study are shown in Table 1. After removing observations with missing data, all analyses were conducted using a sample of 117 ENGOs. Among respondent organizations, 71% had a formal structure (e.g., association, foundation) instead of being organized as an informal group, initiative, platform, etc. Most were young, and 69% were founded after 2010. On average, their geographical scope is relatively narrow; 66% operate at the local level instead of the subregional or regional level. While 59% of ENGOs have an annual budget of more than ten thousand TL, only 46% have 50 or more members. These descriptive statistics imply the significant inadequacies of local ENGOs regarding capacity, resources, and experience.

Table 1 also shows several significant correlations between the independent and dependent variables. As the study involves a set of non-continuous, discrete variables that imply monotonic relationships, correlations were calculated using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, ρ (rho). ENGOs with an activist identity are likely to engage in higher levels of strategic action (ρ = 0.186, p < 0.05) and build significantly fewer ties with the national government (ρ = − 0.294, p < 0.01) and the private sector (ρ = − 0.319, p < 0.01). Having a larger issue scope is positively associated with using a higher degree of strategic actions (ρ = 0.332, p < 0.01), building stronger ties with other ENGOs (ρ = 0.397, p < 0.01), and negatively associated with building ties with local administrations (ρ = − 0.292, p < 0.01) and the state (ρ = − 0.236, p < 0.05). Local ENGOs that pursue transformational goals correlate with taking direct strategic actions (ρ = 0.235, p < 0.01) and collaborating with other ENGOs (ρ = 0.391, p < 0.01). However, the same organizations are less likely to form relationships with local administrators (ρ = − 0.394, p < 0.01), government authorities (ρ = − 0.247, p < 0.05), and the private sector (ρ = − 0.360, p < 0.01). Following informational goals is negatively associated with building ties with other ENGOs (ρ = − 0.188, p < 0.05), whereas it is positively associated with having ties with the state (ρ = 0.247, p < 0.05) and with the private sector (ρ = 0.314, p < 0.01).

Meaningful correlations are also observable between the control variables and research model variables. While having a formal structure is negatively associated with collaborating with other ENGOs (ρ = − 0.194, p < 0.05), larger ENGOs (> 50 members) are more likely to build relationships with the private sector (ρ = 0.263, p < 0.01). ENGOs with a narrow geographical scope are more likely to pursue transformational goals (ρ = 0.253, p < 0.01), but are less likely to have informational goals (ρ = − 0.228, p < 0.01). The same ENGOs also have a lower probability of building connections with national government (ρ = − 0.310, p < 0.01) and the private sector (ρ = − 0.226, p < 0.05). A higher annual budget (> 10.000 tl) is significantly associated with following an informational goal (ρ = 0.237, p < 0.05) and having stronger ties with the private sector (ρ = 0.170, p < 0.05). Finally, while local ENGOs with formal structures and larger budgets are less likely to assume activism as their core identity (ρ = − 0.219; ρ = − 0.221, p < 0.05, respectively), younger ENGOs are more likely to assume activism (ρ = 0.185, p < 0.05).

Hypothesis testing

For the hypothesis testing, we performed different types of regression analyses. To test Hypotheses 1, 3, and 5, we developed a Poisson regression model (Table 2). Poisson regression is a generalized linear model (GLM) type of regression, which uses a log-transformed dependent variable. It is typically adopted when the rate (number of events) per subject should be predicted in a model (Agresti 2007). Because one of the dependent variables of the study, ENGOs’ level of strategic actions, represents a count variable (the total number of different activities), a Poisson regression model was implemented. Because the mean of the variable is higher than its variance, negative binomial regression was not preferred.

For the hypotheses developed to test the impact of predictor variables on the strength of ties with other ENGOs (Hypotheses 2a, 4a, and 6a), a multiple linear regression model was built (Table 3). The reason for this is that tie strength with other ENGOs was measured at an interval (scale) level (Keith 2014). In the model, a stepwise procedure was followed: While model 1 is composed of the control variables only, model 2, model 3, and model 4 present the impact and contribution of each predictor variable gradually.

Finally, logistic regression models were used to test Hypotheses 2b, 4b, and 6b (Table 4). The dependent variables in these hypotheses are measured at the nominal level, conveying information on whether something does or does not happen (Agresti 2007; Long 1997). Specifically, we seek to understand what predicts the probability of a local ENGO engaging in ties with local administrations, the national government, and the private sector. Accordingly, binary logistic regression is an appropriate choice (Long 1997).

Predicting the engagement in strategic actions (Poisson regression)

As Table 2 shows, there are statistically significant results for the model in which the degree of strategic actions by ENGO is the dependent variable. Having an activist identity is significantly related to engaging in strategic actions (Wald = 6.781, p < 0.01). The scope of environmental issues that constitute the ENGO agenda also predicts the probability of using higher degrees of strategic action (Wald = 23.826, p < 0.01). Thus, Hypotheses 1 and 3 were supported. Finally, the results in Table 2 show that when ENGOs have a transformative goal, they are more likely to engage in confrontational actions (Wald = 11.445, p < 0.01). This finding also supports Hypothesis 5.

It should also be noted that the model fit indices represented a good fit for the overall Poisson model. Table 2 reports the likelihood ratio chi-square of 96.02 with 10 degrees of freedom (df) and a significance level of p < 0.001. This p level indicates that the goodness-of-fit test can be taken seriously, and provides evidence that the model is fit.

Predicting the strength of ties with other ENGOs (multiple linear regression)

Table 3 presents the linear regression results for the strength of ties with other ENGOs as the dependent variable. Several meaningful effects were found in model 4 (complete models with all the predictors). First, Table 3 shows that, if the focal ENGO deals with a higher number of environmental issues, it builds stronger ties with other ENGOs (β = 0.316, p < 0.01). Hence, Hypothesis 4a is supported. Similarly, pursuing a transformative goal relates to a higher intensity of interactions with other ENGOs (β = 0.214, p < 0.05), whereas following an informational goal decreases this intensity (β = − 0.214, p < 0.05). Therefore, Hypothesis 6a was also supported. By contrast, having an activist identity did not predict the strength of ties with other ENGOs; thus, Hypothesis 2a was not supported.

Although it was not hypothesized in the study, we also examined whether the three cognitive filters also predict the overall strength of a local ENGO’s ties with any stakeholder. Among the three filter categories, only having an informative goal significantly increases the overall interaction level of ENGOs with diverse actors (β = 0.218, p < 0.05). Some of the control variables also predict overall tie strength; when the ENGO is young (β = − 191, p < 0.05), has a formal structure (β = − 0.218, p < 0.05), and a limited geographical scale (β = − 0.288, p < 0.01), the total interaction intensity decreases.

Predicting the relationships with other actors (binary logistic regression)

Table 4 summarizes the results for ENGO relationships with local administrations, the government, and the private sector using the binary logistic regression procedure. The tests of the model coefficients in the table represent a good fit for each model. The chi-square statistics are all significant at the level of p < 0.01. The log-likelihood and Nagelkerke R2 (as a pseudo-R2) values provide additional evidence that all three models are valuable. The test values of 0.252, 0.271, and 0.465 suggest that between 25.2 and 46.5% of the variability in the dependent variables is explained by the independent variables. The Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test is often considered the best indicator of the fit of logistic regression models. To provide evidence of a good fit, the null hypothesis should not be rejected. As this is the case for each of the three models, we have additional evidence for the reliability of our models.

The results show that although having an activist identity has no impact on the number of ties with local administration, it significantly decreases the odds of local ENGO building relationships with the national government (Wald = 5.607, p < 0.05) and private sector (Wald = 10.879, p < 0.01). Hence, Hypothesis 2b was partially supported. As for the second independent variable, we found that dealing with a larger number of environmental issues (issue scope) weakens the probability of local ENGOs developing connections with local authorities (Wald = 5.809, p < 0.05), whereas it does not predict the likelihood of having ties with the national government and the private sector. Therefore, Hypothesis 4b was not supported. The last independent variable of the study constituted local ENGOs with either a transformational or informational goal. The binary logistic regression results indicate that pursuing an informational goal significantly increases the probability of developing ties with government agencies (Wald = 4.467, p < 0.05) and the private sector (Wald = 3.670, p < 0.05); however, it has no impact on building connections with local authorities. In line with the study predictions, data show that having a transformational goal weakens the probability of local ENGOs developing networks with both local authorities (Wald = 5.393, p < 0.05) and the private sector (Wald = 6.806, p < 0.01) to a significant degree. However, no such impact was found in the ties with the national government. Consequently, Hypothesis 6b was only partially supported.

Discussion

Our findings show that even with other vital organizational characteristics and resources (e.g., size, age, formalization, location, budget) controlled and POS remaining constant, cognitive filters influence local ENGOs’ strategic actions considerably. The nature and type of interactions with diverse actors are also associated with ENGOs’ core identity, the scope of environmental issues, and the primary goal. Local ENGOs claiming an activist identity, working on a larger number of issues, and pursuing a transformational goal tend to undertake a higher degree of strategic action. They also develop stronger ties with other environmental groups, while their tendency to collaborate with local administrations, national government, and private sector actors is weaker.

Regarding our first filter, activist identity, we received support for Hypothesis 1, partial support for Hypothesis 2b, and no support for Hypothesis 2a. Data shows that local ENGOs claiming an activist identity engage in strategic actions more often than those without this claim. As anticipated, they also have a lower probability of building ties with national government and private sector. However, contrary to our initial expectations, they do not have weaker ties to local administrations or stronger ties to other ENGOs. For the former, activism-oriented ENGOs might not be evaluating possible partnerships with local administrators as a threat because of the high levels of social belonging and interpersonal ties. We speculate that the reason behind the latter finding could be the incongruence between local ENGOs’ core values, dissimilar environmental priorities, and diverging preferences for swift action (Bernstein and Olsen 2009; Dalton et al. 2003). To attain results, an activist identity should be translated into “embedded activism,” which includes a coordinated and collaborative approach between social movements (Schifeling and Soderstrom 2022; Schmitt et al. 2019). The results imply that there may be some obstacles in this translation process.

Concerning our second filter, issue scope, we found support for Hypotheses 3 and 4a but no support for Hypothesis 4b. This implies that local ENGOs focusing on a broader issue scope tend to participate in confrontational practices more frequently than those focused on narrower issues. Additionally, they tend to build stronger ties with other ENGOs than those focusing on a limited number of environmental issues. However, they do not exhibit a higher probability of networking with local administrations, the public sector, or the private sector. It can be suggested that while working on a wide range of issues promotes more interaction among ENGOs, it does not necessarily result in increased engagement with other actors, such as local governments, national governments, or the private sector. While dealing with many issues simultaneously may enhance the chances of alignment with other ENGOs, it might facilitate conflicts and tensions with the state and businesses (Asproudis and Weyman-Jones 2020) because of divergent interests (e.g., protection of the environment, economic growth, and profits).

About our last filter, transformational vs. informational goal, we found support for Hypothesis 5 and Hypothesis 6a, but only partial support for Hypothesis 6b. It was observed that local ENGOs with transformational goals tend to engage in strategic actions more frequently and build stronger ties with other ENGOs. As expected, local ENGOs with informational goals have a higher probability of building ties with the national government and private sector, whereas those with a transformational goal are less likely to form ties with local governments or the private sector. However, we did not find evidence suggesting that local ENGOs with a transformational goal have a lower probability of building ties with the state or that local ENGOs with informational goals are more likely to establish ties with local authorities. These results advocate the necessity of developing a more nuanced perspective on local ENGOs’ goals and portraying the complexity of their relationships with diverse stakeholders.

Theoretical and practical implications

While advancing the existing literature on environmental organizations, this article opens the way for future investigations into how cognitive filtering can stimulate particular forms of environmental action at the local level rooted in the community. First, our findings contribute to the two main premises in social movement theory, RMT, and POS, by highlighting the importance of intangible, less visible, ideological dimensions in mobilizing for environmental causes (Diani and Rambaldo 2007; Diani and Pilati 2011; Zchout and Tal 2017). The study supports earlier theorizations on how ENGOs behave differently depending on their ideological orientations, as these orientations lead to different interpretations of the external conditions, the significance of topics, and outside expectations (Zald 2000; Carmin and Balser 2002). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in which these influences were empirically tested using data from many local ENGOs. It is also among the few studies in which the impacts of an ENGO’s organizational identity, environmental issue scope, and core goals have been theoretically and empirically distinguished. The study results suggest that each of these factors has distinctive, independent effects on what tactics are employed and what types of relationships are preferred by a local ENGO.

Second, this study provides new insights into the nature of environmental efforts at the local level in developing countries. Although local grassroots movements are associated with particular forms of action and ties (Andrews and Edwards 2005; Saunders 2007), our findings reveal that they show important diversity in these domains. Ideological plurality produces different decisions and actions for local ENGOs. Specifically, if a local ENGO declares an activist identity, works on a more significant number of issues, and adopts transformative goals, it is more likely to implement direct visible actions. These ENGOs develop stronger relationships with other environmental groups, but weaker relationships with the state and private sectors. Thus, it can be concluded that specific ideological patterns pave the way for different ENGO choices to select actions and connections for environmental advocacy.

Third, although claiming an activist identity and dealing with a large range of environmental issues reduce collaboration probabilities with state agencies and market actors, no impact was found on possible networks with local governments. This implies that many local ENGOs share common concerns with local authorities about environmental challenges in their region and are willing to collaborate. Another interesting finding relates to how local ENGOs’ diverse environmental goals encourage or discourage relationships with particular external actors. Thus, our study puts a new light on the impact of ENGOs’ cognitive filters (e.g., Carmin and Balser 2002), framing and reframing (e.g., Benford and Snow 2000), and strategic discourses (e.g., Sillince and Brown 2009) on the treatment of different field actors.

Fourth, our knowledge of environmentalism in developing countries has been limited mainly to large, national, and professional ENGOs gathered via case-based analysis. Our findings from an extensive survey of local ENGOs in Turkey indicate how national/international ENGOs and local grassroots organizations may differ in several dimensions. Similarly, the literature’s environmental discourses and cognitive frames are typically presented as theoretical typologies or case-based qualitative analyses (Alcock 2008; Ritter and Thaler 2022). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first quantitative and comprehensive analysis of the adopted cognitive filters and their impact on ENGO outcomes.

Finally, our study provides practical implications for environmental activism. We find that cognitive filters influence local ENGOs’ strategic actions considerably and that ENGOs’ nature and type of interactions with diverse actors are associated with their core identity claim. Hence, while searching for other ENGOs to collaborate over a certain goal, local ENGOs need to recall that ENGOs with a transformational goal tend to engage in confrontational actions more.

Limitations and future research suggestions

Our study has some methodological and theoretical limitations. First, the research was conducted using quantitative data collected from environmental organizations via a cross-sectional survey based on self-reports. Although CMV is a possible limitation, several procedural remedies and two statistical post hoc tests indicated that it might not be a significant concern in this study. Nevertheless, future research should utilize longitudinal designs to detect suggested causal relationships without suffering from common method bias. Second, our assessments hold true for small local ENGOs in developing countries. Generalizations to other contexts, such as supranational ENGOs, should be performed with caution (Nasiritousi et al. 2016). Despite having an activist identity and pursuing confrontational goals in one country, supranational ENGOs may adopt different strategic actions in various countries.

Furthermore, examining the specific interaction effects between the studied variables and other organizational and contextual factors can provide a better understanding of how local ENGOs behave. More refined assessments of the relationship between organizational values, beliefs, collective action choices, and strategic ties could also be made by adopting in-depth qualitative methods, such as field observations, interviews, and survey design. While our study enhances the understanding of ENGO behaviors outside the typically developed country context, additional research is needed in which data from diverse national and regional contexts are compared in cross-country inquiries. Conducting comparative case analyses that investigate local struggles undertaken by ENGOs against environmental injustice and ecological collapse in different parts of the world could be particularly helpful.

We also recommend that researchers pay closer attention to how different identities, goals, and environmental issue priorities make ENGOs distinguish between alternative networks and possible collaboration partners in strategic action fields (Diani and Pilati 2011; Fligstein and McAdam 2012). New studies might clarify how ENGOs’ cognitive filters and frames of meaning favor particular relationships while disapproving others.

Conclusion

This study examined whether, and how, identity claims and other cognitive filters play a role in shaping local ENGO activities and relationships with diverse actors in developing countries. Through a quantitative analysis of 117 ENGOs in one of the largest regions of Turkey, the Aegean Region, we found support for our theoretical propositions. We found that while several internal and external factors influence ENGO processes and outcomes, activist identity, large issue scope, and transformational goals have a fundamental impact on the action choices and networking behaviors of ENGOs in developing country contexts. Our multiple regression results show that, even with other vital organizational characteristics and controlled resources, claiming an activist identity, pursuing various issues together, and having a confrontational goal influence local ENGOs’ strategic actions and the nature and type of interactions. As such, local ENGOs with an activist identity, working on diverse issues, and pursuing transformational goals tend to engage more in confrontational actions. They also develop stronger ties with other environmental groups, while their tendency to collaborate with local administrations, the national government, and private sector actors are weaker.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this research are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Adaman F, Akbulut B, Arsel M (2017) Neoliberal Turkey and its discontents: economic policy and the environment under Erdoğan. I. B. Tauris, London

Agresti A (2007) An introduction to categorical data analysis (2nd Ed). John Wiley & Sons

Alcock F (2008) Conflicts and coalitions within and across the ENGO community. Global Environ Polit 8:66–91. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep.2008.8.4.66

Andrews KT, Edwards B (2005) The organizational structure of local environmentalism. Mobil: Int J 10:213–234. https://doi.org/10.17813/maiq.10.2.028028u600744073

Asproudis E, Weyman-Jones T (2020) How the engos can fight the industrial/business lobby with their tools from their own field? Engos participation in emissions trading market. Sustainability 12:8553. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208553

Baumgartner H, Weijters B, Pieters R (2021) The biasing effect of common method variance: some clarifications. J Acad Mark Sci 49:221–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-020-00766-8

Benford RD, Snow DA (2000) Framing processes and social movements: an overview and assessment. Ann Rev Sociol 26:611–639. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.611

Bernauer T, Betzold C (2012) Civil society in environmental governance. J Environ Dev 21:62–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/1070496511435551

Bernstein M, Olsen KA (2009) Identity deployment and social change: understanding identity as a social movement and organizational strategy. Soc Compass 3:871–883. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9020.2009.00255.x

Berny C, Rootes C (2018) Environmental NGOs at crossroads? Environ Polit 27:947–972. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2018.1536293

Betsill MM, Corell E (2001) NGO influence in international environmental negotiations: a framework for analysis. Global Environ Polit 1:65–85. https://doi.org/10.1162/152638001317146372

Carmin J (2010) NGO capacity and environmental governance in Central and Eastern Europe. Acta Polit 45:183–202. https://doi.org/10.1057/ap.2009.21

Carmin J, Balser DB (2002) Selecting repertoires of action in environmental movement organizations. Organ Environ 15:365–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026602238167

Dalton RJ, Recchia S, Rohrschneider R (2003) The environmental movement and the modes of political action. Comp Pol Stud 36:743–771. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414003255108

Dellmuth LM, Bloodgood EA (2019) Advocacy group effects in global governance: populations, strategies, and political opportunity structure. Int Groups Advocacy 8:255–269. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41309-019-00068-7

DERBIS (2021) Turkish Republic Ministry of Interior, General Directorate of Civil Society Relations. https://www.siviltoplum.gov.tr/derneklerin-faaliyet-alanlarina-gore-dagilimi. Accessed 12 Aug 2021

Diani M, Rambaldo E (2007) Still the time of environmental movements? A local perspective. Environ Polit 16:765–784. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644010701634109

Diani M, Donati PR (1999) Organizational change in Western European environmental groups: a framework for analysis. Environ Polit 8:13–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644019908414436

Diani M, Pilati K (2011) Interests, identities, and relations: drawing boundaries in civic organizational fields. Mobil: Int Q 16:265–282. https://doi.org/10.17813/maiq.16.3.k301j7n67p472m17

Dreiling M, Wolf B (2001) Environmental movement organizations and political strategy: tactical conflicts over NAFTA. Organ Environ 14:34–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026601141002

Einwohner R (2002) Bringing the outsiders in: opponents’ claims and the construction of animal rights activists’ identity. Mobil: Int Q 7 253–268. https://doi.org/10.17813/maiq.7.3.x726315p10013277

Feliciano D, Sobenes A (2022) Stakeholders’ perceptions of factors influencing climate change risk in a Central America hotspot. Reg Environ Change 22:23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-022-01885-4

Fligstein N, McAdam D (2012) A theory of fields. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Gamson WA, Fireman B, Rytina S (1982) Encounters with unjust authority. Dorsey, Homewood

Gavetti G, Levinthal D (2000) Looking forward and looking backward: cognitive and experiential search. Adm Sci Q 45:113–137. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666981

Gönenç D (2021) Litigation as a strategy for environmental movements questioned: an examination of Bergama and Artvin-Cerattepe struggles. J Balkan near East Stud 24(2):303–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/19448953.2021.2006004

Gronow A, Yla-Anttila T (2019) Cooptation of ENGOs or treadmill of production? Advocacy coalitions and climate change policy in Finland. Policy Stud J 47:860–881. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12185

Hadden J, Bush SS (2021) What is different about the environment? Environmental INGOs in comparative perspective. Environ Polit 30:202–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2020.1799643

Hamilton-Webb A, Naylor R, Manning L, Conway J (2019) Living on the edge: using cognitive filters to appraise experience of environmental risk. J Risk Res 22:303–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2017.1378249

Heaney MT, Rojas F (2014) Hybrid activism: social movement mobilization in a multimovement environment. Am J Sociol 119:1047–1103. https://doi.org/10.1086/674897

Hess DJ, Satcher LA (2019) Conditions for successful environmental justice mobilizations: an analysis of 50 cases. Environ Pol 28:663–684. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2019.1565679

Horowitz J (2017) Who is this “we” you speak of? Grounding activist identity in social psychology. Socius 3:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023117717819

Inal O, Turhan E (2019) Transforming socio-natures in Turkey: landscapes, state and environmental movements. Routledge, London

Jordan PJ, Troth AC (2020) Common method bias in applied settings: the dilemma of researching in organizations. Aust J Manag 45:3–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0312896219871976

Kadirbeyoğlu Z, Adaman F, Özkaynak B, Paker H (2017) The effectiveness of environmental civil society organizations: an integrated analysis of organizational characteristics and contextual factors. Int J Volunt Nonprofit Organ 28:1717–1741. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-017-9848-y

Keith TZ (2014) Multiple regression and beyond: an introduction to multiple regression and structural equation modeling (2nd Ed). Routledge, New York

Lindell MK, Whitney DJ (2001) Accounting for common method variance in cross sectional research designs. J Appl Psychol 86:114–121. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.114

Long JS (1997) Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables. Sage

Martinez-Alier J (2002) The environmentalism of the poor: a study of ecological conflicts and valuation. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

McCarthy JD, Zald MN (1977) The resource mobilization and social movements: a partial theory. Am J Sociol 82:1212–1241. https://doi.org/10.1086/226464

Meyer DS, Staggenborg S (1996) Movements, countermovements, and the structure of political opportunity. Am J Sociol 101:1628–1660. https://doi.org/10.1086/230869

Murphy-Gregory H (2018) Governance via persuasion: environmental NGOs and the social license to operate. Environ Polit 27:320–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2017.1373429

Nasiritousi N, Hjerpe M, Linnér BO (2016) The roles of non-state actors in climate change governance: understanding agency through governance profiles. Int Environ Agreements 16:109–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-014-9243-8

Onwachukwu CI, Yan KI, Tu K (2021) The causal effect of trade liberalization on the environment. J Clean Prod 318:128615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128615

Özen H, Doğu B (2020) Mobilizing in a hybrid political system: the Artvin case in Turkey. Democratization 27(4):624–642. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2019.1711372

Pacheco-Vega R, Murdie A (2020) When do environmental NGOs work? A test of the conditional effectiveness of environmental advocacy. Environ Polit 30:180–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2020.1785261

Paker H, Adaman F, Kadirbeyoğlu Z, Özkaynak B (2013) Environmental organizations in Turkey: engaging the state and capital. Environ Polit 22:760–778. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2013.825138

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method biases in behavioural research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88:879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Polletta F, Jasper JM (2001) Collective identity and social movements. Ann Rev Sociol 27:283–305. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.283

Porac JF, Thomas H (1990) Taxonomic mental models in competitor definition. Acad Manag Rev 15(2):224–240. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1990.4308155

Raffaelli R, Glynn MA, Tushman M (2019) Frame flexibility: the role of cognitive and emotional framing in innovation adoption by incumbent firms. Strateg Manag J 40:1013–1039. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3011

Richards JP, Heard J (2005) European environmental NGOs: issues, resources, and strategies in marine campaigns. Environ Polit 14:23–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/0964401042000310169

Ritter E, Thaler GM (2022) Technical reform or radical justice? Environmental discourse in non-governmental organizations. Environ Plan E: Nat Space 6:2071–2095. https://doi.org/10.1177/25148486221119750

Rootes C (2003) The transformation of environmental activism: an introduction. In: Rootes C (ed) Environmental protest in Western Europe. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 1–19

Saunders C (2007) Using social network analysis to explore social movements: a relational approach. Soc Mov Stud 6:227–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742830701777769

Saunders C (2008) Double-edged swords? Collective identity and solidarity in the environment movement1. Br J Sociol 59:227–253. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2008.00191.x

Schifeling T, Soderstrom S (2022) Advancing reform: embedded activism to develop climate solutions. Acad Manag J 65:1775–1803. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2019.0769

Schmitt MT, Mackay CM, Droogendyk LM, Payne D (2019) What predicts environmental activism? The roles of identification with nature and politicized environmental identity. J Environ Psychol 61:20–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2018.11.003

Schoon M, York A, Sullivan A, Baggio J (2017) The emergence of an environmental governance network: the case of the Arizona borderlands. Reg Environ Change 17:677–689. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-016-1060-x

Shwom R, Bruce A (2018) U.S. non-governmental organizations’ cross-sectoral entrepreneurial strategies in energy efficiency. Reg Environ Change 18:1309–1321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-018-1278-x

Sillince JA, Brown AD (2009) Multiple organizational identities and legitimacy: the rhetoric of police websites. Hum Relat 62:1829–1856. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709336626

Smith WK, Tushman ML (2005) Managing strategic contradictions: a top management model for managing innovation streams. Organ Sci 16:522–536. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1050.0134

Snow DA, Benford RD (1988) Ideology, frame resonance, and participant mobilization. In: Klandermans B, Kriesi H, Tarrow S (eds) International Social Movement Research Vol. 1. Greenwich, CT: JAI, pp 197–218

Tarrow S (2008) States and opportunities: the political structuring of social movements. In: McAdam D, McCarthy JD, Zald MN (eds) Comparative perspectives on social movements: political opportunities, mobilizing structures, and cultural framings. Cambridge University Press, pp 41–61

Temper L, del Bene D, Martinez-Alier J (2015) Mapping the frontiers and front lines of global environmental justice: the EJAtlas. J Polit Ecol 22:255–278. https://doi.org/10.2458/v22i1.21108

Tran NV (2020) The environmental effects of trade openness in developing countries: conflict or cooperation? Environ Sci Pollut Res 27:19783–19797. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-08352-9

van der Heijden HA (1997) Political opportunity structure and the institutionalisation of the environmental movement. Environ Polit 6:25–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644019708414357