Abstract

The scale of climate migration across the Global South is expected to increase during this century. By 2050, millions of Africans are likely to consider, or be pushed into, migration because of climate hazards contributing to agricultural disruption, water and food scarcity, desertification, flooding, drought, coastal erosion, and heat waves. However, the migration-climate nexus is complex, as is the question of whether migration can be considered a climate change adaptation strategy across both the rural and urban space. Combining data from household surveys, key informant interviews, and secondary sources related to regional disaster, demographic, resource, and economic trends between 1990 and 2020 from north central and central dryland Namibia, we investigate (i) human migration flows and the influence of climate hazards on these flows and (ii) the benefits and dis-benefits of migration in supporting climate change adaptation, from the perspective of migrants (personal factors and intervening obstacles), areas of origin, and areas of destination. Our analysis suggests an increase in climate-related push factors that could be driving rural out-migration from the north central region to peri-urban settlements in the central region of the country. While push factors play a role in rural-urban migration, there are also several pull factors (many of which have been long-term drivers of urban migration) such as perceived higher wages, diversity of livelihoods, water, health and energy provisioning, remittances, better education opportunities, and the exchange of non-marketed products. Migration to peri-urban settlements can reduce some risks (e.g. loss of crops and income due to climate extremes) but amplify others (e.g. heat stress and insecure land tenure). Adaptation at both ends of the rural–urban continuum is supported by deeply embedded linkages in a model of circular rural–urban-rural migration and interdependencies. Results empirically inform current and future policy debates around climate mobilities in Namibia, with wider implications across Africa.

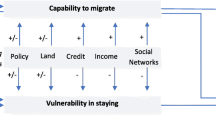

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Throughout human history, migration has been a commonly adopted strategy for managing risk, exploiting new resources, generating livelihoods and incomes, and for coping and surviving (Muñoz-Moreno and Crawford 2021). In the Anthropocene, environmental factors are increasingly recognised as contributing to human migration (Mastrorillo et al. 2016; Mueller et al. 2020). New terms, such as ‘environmental mobility’ or ‘environmental movements’, have been coined to describe these rising trends (Rigaud et al. 2018). Global forecasts suggest the likelihood of 150–200 million ‘environmental migrants’ by 2050 (Clement et al. 2021; Cundill et al. 2021). The scale of the issue is both vast and urgent and represents a clear human predicament and sustainability challenge, in what is progressively being framed as the ‘environmental migration-development nexus’ (Neumann and Hilderink 2015).

Clearly, environmental mobility is a complex multi-dimensional phenomenon, characterised by duration (e.g. seasonal, permanent, short-, medium-, or long-term), circumstance (e.g. progressive, sudden, proactive, or reactive), destination (e.g. internal or international), and choice (e.g. voluntary or forced) (Waldinger 2015; Rigaud et al. 2018; Clement et al. 2021). Migration is likewise a networked phenomenon, in which individuals, households, and groups are situated within ‘plural social networks’ that influence their ability to cope and adapt (Bilecen and Lubbers 2021). Set against this multi-dimensionality, there is a growing awareness that the environment interacts with non-environmental structural factors such as socio-economic, cultural, historical, political, and institutional conditions to influence migration decisions (Black et al. 2011; Hermans and McLeman 2021; Mastrorillo et al. 2016).

Climate change is increasingly viewed as the preeminent environmental driver of human movement, as the Clement et al. (2021) states: “Mobility is emerging as the human face of climate change” (Rigaud et al. 2018, pp. 1). Consequently, a subset of environmental mobility is progressively being framed through a climate change lens, frequently referred to as ‘climate-induced migration’ or simply ‘climate migration’, which principally encompasses “slow-onset impacts of climate change on livelihoods owing to shifts in water availability and crop productivity, or to factors such as sea level rise or storm surge” (Rigaud et al. 2018, pp. vii).

The climate migration narrative is not without criticism, however. It has been described as potentially misleading because of its frequently highly politicised usage, with the alternative term ‘climate mobilities’ put forward as better encapsulating the way people move as part of normal social life (Boas et al. 2019; Wiegel et al. 2019). Relatedly, climate change—rather than stimulating movement—may also cause people to be locked into a place (Call et al. 2017), giving rise to the much more understudied notion of climate immobility (Zickgraf 2019). Further, the strength of the evidence base for climate migration is often varied, due to, for instance, methodological differences between studies, the scale of studies, or a lack of suitable data (Delazeri et al. 2021).

Where climate is evidently a significant driver, other factors are often perceived by local people to be more proximal. For instance, in Ghana, Bangladesh, and India, few households identify environmental risks as the primary driver for past migration decisions. Instead, households perceive increased drought and insecurity to both reduce future migration intentions (Adger et al. 2021). This resonates with findings demonstrating that migrants frequently avoid or resist environmental explanations, favouring instead economic narratives of migration (Anderson and Silva 2020; Artur and Hilhorst 2012; Black et al. 2011; Hoffmann et al. 2019; McCubbin et al. 2015). In part, this may be indicative of the complex and context-specific nature of climate-related environmental change and human migration, which is reflective of not only the diversity and magnitude of climate drivers but also the characteristics and vulnerabilities of impacted populations (Delazeri et al. 2021; Falco et al. 2019). At the same time, climate change, via its interaction with structural factors, may directly and indirectly influence migration through multiple pathways (Cattaneo et al. 2019; Rigaud et al. 2018).

Whilst acknowledging these important complexities, undeniably, in a more climate-affected world, climate migration or mobilities, especially internal migration, is a growing phenomenon—particularly across the Global South (Clement et al. 2021). Across Africa, climate change projections suggest a greater frequency and intensity of natural hazards (Williams et al. 2019), increasing the risks of trade-offs across sectors and resources. Trade-offs particularly manifest through impacts on water availability and seasonal reliability—undermining key components of sustainable development (Mpandeli et al. 2018; Nhamo et al. 2018; Pardoe et al. 2018; Mabhaudhi et al. 2019). For example, changes in the intensity and frequency of extreme events (e.g. drought and floods)—due to changes in rainfall patterns—may reduce agricultural and pastoral productivity and raise food commodity prices (Marchiori et al. 2012; Morrissey 2013; Wiederkehr et al. 2018). Further, as highlighted in Kenya, climate change can enhance domestic livelihood vulnerabilities to exogenous drivers of change (e.g. oil price shocks) (Wakeford 2017). In sub-Saharan Africa, estimates suggest up to 86 million internal climate migrants by 2050 (Rigaud et al. 2018). Recent analyses in West Africa (Rigaud et al. 2021a) and Lake Victoria Basin countries (Rigaud et al. 2021b) suggest up to 32 million and 16.6–38.5 million internal climate migrants by 2050, respectively. Responding to the sheer scale of the challenge, the United Nations’ International Organization for Migration, in October 2021, launched a decadal institutional strategy on migration, environment, and climate change (IOM 2021).

Today, migration can be seen as a rational climate adaptation strategy (Rigaud et al. 2018; Thiede et al. 2016). Frequently, the decision to migrate as a form of adaptation is often from rural hinterlands, where there is high dependence on climate-sensitive livelihood activities, towards urban centres that can offer alternative means of making a living. In their analysis of 63 studies covering over 9700 rural households in dryland sub-Saharan Africa, Wiederkehr et al. (2018) found that 23% of households employed migration to boost household income, alongside alternative crop, livestock, soil, and water management.

The interactions between climate and the structural factors that create or entrench vulnerability are important in decisions to migrate and be seen as key ‘pull’ factors. For example, Hoffmann et al. (2019) explored the motivation of rural–urban migrants who moved from the Himalaya foothills of Uttarakhand to its capital city, Dehradun. Authors found that education, employment opportunities with the associated income, and facilities were major reasons for migration despite evidence of negative environmental change. These pull factors can be thought of as the benefits of migration, but there are many benefits associated with moving into the urban or peri-urban space that are often not fully considered.

Rising rural–urban migration contributes to unplanned urbanisation and the growth of peri-urban informal settlements. Here, people tend to engage in casual work, self-employment, petty trading, and small-scale informal enterprises, providing a reservoir of goods, services, and labour to the wider city, contributing to a dynamic informal economy (UN-Habitat 2016). Frequently, in these spaces, new migrants and lower-income groups may be pushed to the margins of urban development and, due to the lack of basic infrastructure and often poorly constructed and fragile housing, are not prepared for the increased frequency of climate-related hazards, particularly floods, storm events, or heat waves (Satterthwaite et al. 2020). They may also face many other challenges such as a lack of basic services like water and sanitation creating greater health risks (Niva et al. 2019). Vinke et al. (2020) point out that the adaptive benefits and dis-benefits of migration are highly community specific and contingent, as migration is frequently not an anticipatory process, nor is it a first-choice option in cases where migration involves an entire household, and indeed it may lead to increased deprivation and vulnerability. Here, we define dis-benefits as the negative consequences of human-resource interactions or loss from climate migration that can be managed and mitigated at varying scales and levels (Dennis et al. 2020; Mycoo et al. 2022; Lázár et al. 2020; Rendon et al. 2019; United Nations 2021).

However, peri-urban areas are dynamic and form a functional space connecting the urban to the rural (via housing, infrastructure, health, education), people and landscapes via flows of goods and services, financial investments, and culture and family (Hutchings et al. 2022; UN Habitat 2016). Cities drive change in rural areas via increasing demand for rural food production (Suckall et al. 2015), off-farm employment opportunities, and the emergence of new markets (FAO 2020), whilst urban-based households depend on rural exchanges to maintain diversified livelihoods. Reciprocal movements back and forth, between rural and peri-urban areas, are tied to strong familial and social networks and the development of multi-local livelihoods, which can be seen as an adaptive strategy in both rural and urban contexts (Djurfeldt 2015; Dodman et al. 2017).

Often only particular members of the family may migrate (e.g. men, youth) which maintains the linkages between those migrating and those staying behind. This is the notion of the so-called stretched family (Porter et al. 2018). Gender, due to its dynamic nature, shapes key vulnerabilities that influence climate migration, particularly through the structuring and stratification of roles in the household and labour markets (Macgregor 2010; Lama et al. 2021). In many cases, this can further enhance pre-existing gender inequalities; in other cases, this can elevate women’s positions and bargaining capacities (Rao et al. 2019). Recent research has also suggested that temporary migration between rural and urban areas may be a more effective adaptation strategy than permanent migration for climate-vulnerable households and communities (Mueller et al. 2020). This strong, reciprocal connection between the rural and the urban could help overcome some of the dis-benefits of migration and strengthen the benefits. Hence, migration as adaptation is highly nuanced and context-specific and a mix of benefits and dis-benefits that are traded-off (Vinke et al. 2020).

Although there is a small but growing body of research concerning environment and climate migration in sub-Saharan Africa, for example, in Burkina Faso (Henry et al. 2004; Nébié and West 2019), Ethiopia (Gray and Mueller 2012; Morrissey 2013; Hermans-Neumann et al. 2017; Groth et al. 2021), Ghana (Adger et al. 2021), Malawi (Lewin et al. 2012; Suckall et al. 2015), Mali (Grace et al. 2018), Mozambique (Anderson and Silva 2020), Niger (Afifi 2011), Nigeria (Dillon et al. 2011), South Africa (Mastrorillo et al. 2016), Tanzania (Hirvonen 2016), Senegal (Hummel 2016), Uganda (Call and Gray 2020), and Zambia (Nawrotzki and DeWaard 2018), there is no overall coherence to this developing corpus of work which limits our understanding of how individuals utilise migration as an potential adaptive strategy. A lack of evidence on the feedback channels by which climate affects migration patterns acts as a further impediment to our understanding (Mueller et al. 2020). Meanwhile, most of the research funding and local implementation in the sub-Saharan African region related to climate resilience focuses on ‘rural’ (e.g. agrarian) themes; even though climate also concerns urban areas and the connections between the rural and urban (Satterthwaite et al. 2020). Understanding the benefits and dis-benefits of migration as a climate adaptation strategy for individuals and their families living across rural and peri-urban areas is crucial for improved monitoring and prediction of internal patterns of migration, for identifying the consequences of such mobility for the communities of origin (rural areas) and communities of destination (peri-urban areas), for managing issues associated with the movement of people and resource flows, and for developing policies and strategies to build resilience to climate change (Borderon et al. 2018). This necessitates understanding not only local, but regional and national trends.

Motivated by these knowledge gaps, we explore the benefits and dis-benefits of rural-peri-urban climate migration and the ensuing rural-peri-urban linkages in Namibia since independence. Peri-urban areas have grown rapidly, concomitant with the general increase in urbanisation since independence, with fewer affordable houses and land supply not meeting demand (Weber and Mendelsohn 2017). Our purpose is to use climate as a lens through which to view reciprocal rural-peri-urban migration, which then lays the ground for a conversation with, for example, traditional structural drivers of mobility, such as economic motivators. In this way, we do not fall into the trap of focusing purely on the climate dimension as a separate issue to the detriment of socio-economic and political factors that may be more front and centre in decision-making around whether to migrate or not. We address the need to understand drivers (push and pull), patterns, and outcomes of migration, particularly for vulnerable communities, along the rural-peri-urban continuum. To this end, our research questions are as follows: (1) what are the patterns of climate change and internal regional migration flows? and (2) using Everett Lee’s influential migration model (Lee 1966), which assesses migration from the perspective of migrants (personal factors and intervening obstacles), areas of origin, and areas of destination, what are the benefits and dis-benefits of climate migration as an adaptive strategy?

Materials and methods

Study country and sites

Namibia was considered an excellent choice to study internal migration related to climate change in Southern Africa for three main reasons. First, the country is characterised by high internal migration rates, land regularisation, and demographic transition—as is the case in many African countries. From the late 1970s, several laws were repealed, instantiated by the South African apartheid administration, constraining the movement of people based on ethnicity (Pickard-Cambridge 1988). Since the 1930s, populations were regulated and much of the land of Northern regions reserved for commercial farming. The 20-year period following independence in 1990 saw the country shift from a primarily rural to urban population (from 44.8 to 55.2%) and move towards a younger society (37% ≤ 15 years, 5% ≥ 65 years, 21.8 years median age) with a lower-than-average level of fertility (3.6 children/woman compared to the sub-Saharan African average of 5) (Pendleton et al. 2014; Demographic Dividend Study Report 2018). Second, as the most arid country in Southern Africa, the connections between water, energy, and food sectors and climate are strong, particularly in terms of spatial interdependencies as well as physical and socio-economic exposure (Republic of Namibia 2002). For example, climate change impacts are manifesting through decreases in water availability, increases in energy prices, limited pasture availability, and rising vector- and water-borne diseases such as malaria, dengue, and cholera (Conway et al. 2015). Multiple droughts have occurred since 2014, with recurrent intermittent wildfires (Kapuka and Hlásny 2020). Climate change is adversely impacting subsistence and commercial agriculture crop and livestock production, which are key sectors for labour income (Humavindu and Stage 2013). Sudden onset flooding events from erratic seasonal rain is high in the northcentral regions of Oshikoto, Omusati, Ohangwena, and Oshana. Future projections of rainfall changes (~ 10–20%) across Angola and Zambia by 2050 suggest reductions of 20–30% in runoff and drainage of perennial rivers in northern Namibia. Meanwhile, central regions will likely experience increased heat stress (World Bank 2021a, b). Third, while Namibia has developed a modern economy with a 30-year average GNI growth rate of 3.75% (Online Resource 1 Fig. S1 and S2), it continues to suffer from persistent macroeconomic imbalances coupled with long-standing issues of inequality. The Gini coefficient in 2015 was 59.1%, making it the second most unequal country worldwide (World Bank 2021a, b). Many communal areas still feel multiple levels of neglect from public service delivery and lack of land rights, undermining communal land managers’ self-sufficiency (Mbidzo et al. 2021).

Namibia has a varied biocultural and geological diversity and climate. With an area of 824,292 km2 and a population of only 2.49 million, Namibia is the second most sparsely populated country in the world (2.5 people/km2) (NSA 2011). Topographically, Namibia has a low-lying Atlantic coastal region, whilst the elevation increases inland. Climatologically, the country is hot and dry with uneven rainfall, experiencing average annual coastal temperatures of 16–22 °C in the north central and eastern areas, with interior climes exhibiting hotter and colder extremes. Rainfall varies considerably north to south, averaging 25 mm year−1 in the south to 600 mm year−1 in the northeast. The principal land types are savannah (64%), dry woodlands and forests (20%), and desert (16%) which crosscut and interconnect to create four biomes: Succulent Karoo, Namib Desert, tree and shrub savannah, and Nama Karoo (Kapuka and Hlásny 2020). We studied the most populous regions (Fig. 1) which also have high climate risk, namely, Khomas in central Namibia and Omusati, Oshikoto, Oshana, and Ohangwena in northcentral Namibia (formerly Owamboland). While these areas represent only 10% of the country’s land surface area, they are home to about half of the population (Angula and Kaundjua 2016).

Study area. Green circles represent the households surveyed. The light brown-shaded regions represent the regions studied using secondary data. The six towns where household surveys or key informant interviews were conducted were Windhoek, Gobabis, Oshakati, Otjiwarongo, Tsumeb, and Ongwediva. In Windhoek we studied constituencies of Tobias Haunyeko, Moses Garoëb, and Samora Machel

Data collection

To combine fine resolution data in rural and peri-urban areas and account for spatial–temporal variability, we applied an interdisciplinary mixed-method approach. We combined key informant interviews and household surveys with longitudinal trend analysis of disasters, resource consumption and production in the water, energy, and food sectors using secondary data.

Household surveys

Following Hummel (2016), we administered 330 household surveys in nine informal settlement destinations in Windhoek, in settlements of Orkuryangava Kilimanjaro (n = 25), Orkuryangava Okahandja Park No. 3 (n = 25), Havana Kabila (n = 25), Havana Cuba (n = 25), Okuryagava Ombili Hakahana Namibia Nalitongwe (n = 25), Okuryangava Ombili Hakahana Eehambo Danehale (n = 26), Okuryangava Ombili Ondidototela (n = 49), Okuryangava Ombili Jonas Haiduwa and Haidure (n = 51), and Okuryangava Ombili Epandulo (n = 7). We selected settlements using the following criteria: (a) high population growth, (b) local expertise indicated that the sites were broadly representative of the area, and (c) we had permission to work in the sites. Within those settlement areas that met our criteria, households were randomly sampled. The sample represented a 57:43 female/male ratio. Respondents ranged in age from 19 to 75 years, averaging 41.3 ± 0.61 years, and represented 27 ethnic groups, predominantly Omuwambo (68.8%), Kavango (13.6%), and Herero (3.6%). We collected the data between 2018 and 2020 in the dry and wet season. We asked participants when they moved to their current residence and where they moved from and to articulate what their motivations, aspirations, and obligations to migrate were in relation to both their community of origin and destination (Porst and Sakdapolrak 2020). Household surveys were designed and captured using QualtricsXM online survey software and were administered in situ using a Samsung Galaxy tablet A7. Following the completion of each respondent survey, data was uploaded onto the secure online survey platform. After completion of the full household survey, survey data was processed and then analysed using Excel Office 365.

Key informant interviews

We conducted informal semi-structured interviews with 125 key informants across six towns (Fig. 1). Towns in the geographic regions of interest were chosen based on the following criteria: (a) they were the origin of the largest proportion of migrants according to our household survey; (b) they have been historically more exposed to extreme climate-related hazards than other settlements; and (c) they are distributed across a rainfall gradient (wetter to drier). On pragmatic grounds, participants were recruited using snowball sampling and included local authority divisions (n = 17) (e.g. human settlements, disaster risk reduction, urban and transport planning, city CEO, mayor), national government (n = 6) (e.g. Namibian Statistics Agency, Ministry of Environment and Tourism), non-governmental and community-based organisations (n = 21) (e.g. Namibian Housing Action Group, Desert Research Foundation, Namibian Chamber of Environment), private companies (n = 17) (e.g. town planners, architectural firms, consultants), community leaders and residents (n = 41) (e.g. Shack Dwellers Federation leaders), researchers (n = 10) (e.g. University of Namibian, Namibian University of Science and Technology), elected councillors and politicians (n = 8), and multilateral organisations and donors (n = 5) (e.g. UNDP, FAO, GIZ, British High Commission). Interview topics covered migration flows; how adaptation is supported or hindered by migration; non-climatic drivers of migration; resource flow connections between markets, settlements, and production sites; and interlinkages in marketed and non-marketed commodities. Following Gemenne and Blocher (2017), anonymised interview transcripts were deductively coded using NVivo (12.0). Key themes corresponded to patterns of migration flows, direct and indirect climatic and non-climate drivers, and rural–urban linkages and the benefits and dis-benefits of migration for migrants themselves, communities of origin, and destination. We acknowledge that our sampling is small compared to the overall population’s size and there is potential for bias; however, efforts were made to reach across scales of administration and government, as well as public, private, and civil society sectors, and thus connect with a diversity of actors and stakeholders operating in this space.

Secondary data sources

Following Call and Gray (2020), we analysed secondary data, as summarised in Table 1. We chose 10-year intervals to compute change over time between 1990 and 2019 for quantitative trend analysis. Due to the spatial and temporal resolution of secondary data types and availability, our focus centred on describing and identifying patterns and associations rather than developing causal links to populate models of migration. Where possible, we performed trend analysis, compared means including post hoc multiple comparison tests, and generated graphical outputs of associations. One-way ANOVAs compared mean variances, while Tukey’s HSD tests examined multiple comparisons. IBM SPSS (v. 27) was used to perform statistical analyses. Sankey diagrams were generated in Excel (Office 365) using the Power-User package. Maps were generated in ArcGIS Pro. Namibian dollar (NAD) values were converted to USD because this is an international currency widely used (1USD = 14.37NAD).

Results

Recent changes in climate-related hazards in north central and central Namibia

Since independence, Namibia has experienced 26 large-scale events spanning 13 floods, eight droughts, and five parasitic, water-related epidemics (Fig. 2). Comparatively more flooding occurred in the north, while droughts dominated in the central and southern regions. Coupled to the geographical heterogeneity of these extreme events is a regional bias in their frequency, with climate-related disasters being higher in the north compared to central and southern regions. Major events occurred in 2000–2002 which affected eight regions, with the impacts during 2010–2011, 2013–2015 and 2019 being especially notable (Fig. 3). The intensity and frequency of these hazards had significant impacts on livelihoods of tens of thousands of people, degrading social networks, disrupting community institutions, and exacerbating land use change.

Sankey diagram showing the connections between geographical regions and climate-related disaster occurrences during 1990–2019. Percentages on connectors relate to the frequency of specific disaster types. Thickness of connectors directly relates to the magnitude of the disaster frequency (North Central, Oshana, Ohangwena, Omusati, Oshikoto; Northeast, Okavango, Caprivi, Zambezi; Northwest, Kuene; Upper Central, Otjozondjupa; Central, Erongo, Khomas, Omaheke; South Central, Hardap; South, Karas)

In north central Namibia, seasonal flooding is connected to the Cuvelai Basin hydrological regime, where water accumulated in the Angolan Highlands moves downstream to the floodplains and interconnected shallow water courses (oshanas). These annual floods (efundja) are important for restoring grazing capacity, fish stocks, and ensuring water reserves for the dry months. In recent years, however, flooding frequency and intensity has increased considerably—affecting up to 70,000 people on an annual basis. Fourteen floods have taken place since 2000 with heavy and erratic rainfall—impacting 1,101,952 people. Significantly, respondents indicated that this flooding frequency and intensity is a driver of their mobility.

Since the 1930s, droughts have impacted large portions of the country, with the 1970–1971 droughts declared the most devastating pre-independence. More recently, the 2015–2016 drought period was especially brutal, affecting 580,000 people with an estimated 80,000–500,000 livestock deaths (Kapuka and Hlásny 2020). In the past, pastoral transhumance practices allowed for the temporary evacuation of drought-stricken range in favour of reserve grazing elsewhere. Such temporary evacuation was facilitated by state-owned areas for emergency grazing. However, with increased commercialisation and land privatisation, this system no longer operates. Instead, only commercial farmers that can rent grazing land retain this practice and procure supplementary feed for livestock.

Communal areas of permanent and semi-permanent cropland are mostly found in the north central region, making people living here particularly vulnerable to climate change (Online Resource 2 Fig. S3-6). Overlaying crop production with years of significant droughts clearly shows associated reductions in cereal harvests across all regions. A 30-year analysis of the Vegetative Health Index indicates that years of major climate-related hazards are associated with the highest vegetation stress (< 35%), while spatial analysis of the Agricultural Stress Index indicates growing drought affecting most severely grassland and cropland areas of the north central regions. We also found, in the north central regions, that the source of household income comes predominantly from subsistence activities.

Patterns of internal regional migration flows

Net regional migration flows (Fig. 4), reproduced from the 2011 census, reveal significant southerly migration from the north central region, mostly from Omusati and Ohangwena, to the central Khomas region, where the capital Windhoek is located. Here, in-migration levels are approximately 75.2%, with Erongo also exhibiting high in-migration (68.6%), while lower levels of migration occur in Karas (15%) and Otjozondjupa (12.9%). Significantly, Khomas and Erongo had more than 40% of their population born elsewhere. Conversely, out-migration ≤ 21.1% occurred in eight of the 13 regions, with the highest levels in Ohangwena (21.1%) and Omusati (17.6%). Although rural to peri-urban flows predominate, reciprocal peri-urban to rural migration patterns are also observed. Illustrating this latter point, one household respondent from Havana, Windhoek, described: “I am just here to sleep, go to work and accumulate money and go back home when I’m old” (R.K., 14/01/2019).

Flow maps indicate net regional flows of migrants between north central and central regions, using data from the 2011 census data. Maps are reproduced with kind permission from Population Census Atlas 2011 (NSA 2013a, b). Blue indicates in-migration, while green represents out-migration. Bar charts compare place of birth to usual residence. Positive values demonstrate net in-migration into regions, whereas negative values represent net out-migration. The figure shows in north central Omusati, people generally in-migrate from Ohangwena and Oshana, while most people out-migrate to Khomas. Ohangwena has more in-migrating from Khomas, as well as Oshana, Oshikoto, and Omusati, while many simultaneously out-migrate to Khomas. In Oshana, most people in-migrate from Ohangwena and Omusati and out-migrate to Khomas and Erongo. In Oshikoto, most people in-migrate from Ohangwena and Oshana and out-migrate to Khomas, followed by Erongo. Importantly, there is also a degree of reciprocal out-migration from Khomas to Erongo, Otjozondjupa, and Oshana. Own calculation from NSA Migration Report (2015), based on 2011 census data

Insights from key informants and the household survey suggested that people’s movement across the landscape is often a staged process, moving from smaller to larger urban areas and then back again. Further, young people (15–24 years old) were also more likely to migrate than older people—as explained by a researcher: “Service delivery is slow, and the youngsters become frustrated. Young people who are unemployed come to look for work or come to study and for more places of recreation. They accumulate and then go back when they are old” (W.S., 10/01/2018). In peri-urban centres, 26.1% of young migrants choose to migrate to gain independence from landlords (n = 86), and another 11.5% migrated to gain independence from extended family members or escape overcrowded living conditions (n = 38). Although more research is needed, many respondents during the household survey stated that men were more likely to migrate than women, due to traditionally higher decision-making power, access to resources, and fewer caring commitments.

One outcome of these inter-regional migration flows is a contribution to changing population demographics. Between 1991 and 2019, rural populations declined from 72.3 to 48.9%, contrasting with urban populations that almost doubled from 27.7 to 51.0%. During the same period, the rural population annual growth rate decreased from 3 to − 0.1%/a, while urban population annual growth rates remained relatively constant from 4.3 to 3.9%. The highest urban annual growth rates were in Oshakati (6.9%), Outapi (5.4%), and Windhoek (4.2%) (Online Resource 3 Fig. S7 and Table S1). While population growth size itself is not indicative of migration, it does infer the overall trend of a shift from a rural to an urban society, and that growth is occurring not only in the central but also north central and north-western centres.

Data from our household survey revealed two interesting points. First, only 26.7% (n = 89) of respondents specified that they came from locations outside Windhoek, while the majority (73.3%) stated they came from other informal settlement locations within the city. This gives a sense of the transience of people’s dwelling places and movements within the peri-urban landscape. This data also suggests that people are beginning to identify these settlements as home—as one respondent remarked: “Some people all they know is the city, this is their only home” (G. D., 10/01/2019). Most (76.9%, n = 256) household respondents living in Windhoek’s peri-urban settlements had been there for 10 years or less, while 22.2% (n = 74) had lived there for more than 10 years, with the average being 8.2 ± 0.3 years. Second, of the 26.7% of those who did identify origin locations outside of Windhoek, our data corresponds with the national data, with more migrants originating from the northern region. Fifty eight of the 89 respondents said they had moved from the northern Omusati, Oshana (Oshakati), and Kavango regions—especially Rundu and other urbanised centres north of Etosha National Park—10 had come from the eastern region of Omaheke from places such as Gobabis and Tlhabanelo, while 7 came from places in the west, namely, Walvis Bay and Swakopmund. Towards southern Namibia, four of the migrants arrived from Rehoboth in Hardap and Keetmanshoop in Karas. In the central region, 10 came from Otjiwarongo and Grootfontein in Otjozondjupa.

Benefits and dis-benefits of climate migration as a climate adaptation strategy

In this section, we draw on data from all our primary sources (household survey and key informant interviews) and national statistics.

From the perspective of the migrant

Vibrant urban centres with generally higher entrepreneurial-based comparative advantages and earning power are attractors for migrants. Such migrants seek to diversify away from a dependence on agricultural production, increase their household incomes, and elevate their socio-economic status. Wages and salaries, indicative of formal sector employment, as a percentage of household income vary significantly across regions (df = 5, F = 139.538, P = 7.84 × 10−20), ranging from 13 to 77% (Online Resource 4 Fig. S8). Tukey’s HSD test revealed that the contribution of wages and salaries to households in the central Khomas and Otjozondjupa regions is significantly higher compared to all north central regions (< 0.001), while in the northern regions, we observed significant differences between Oshana, Ohangwena, and Omusati (< 0.001), Ohangwena and Oshikoto (< 0.001), and Omusati and Oshikoto (0.003).

The pull factors of wages and business in urban areas in central regions, combined with the impacts of climate change drivers on pastoral and agricultural activities in the north central regions, were explained by a town planner: “When livestock dies from drought it means wealth goes down the drain. Horticulture cannot be continued. There is a snowball impact on the poverty cycle. If this happens in the rural areas people can’t do anything and come to Windhoek to find a job. It’s a harsh reality” (R.S., 10/01/2018). A Shack Dwellers Federation representative of the settlement of Freedom Square went on to describe: “In the past, the Herero pastoralists thought the urban centre was a nuisance. But climate change changed their outlook. When they were hard hit from drought, their herd was reduced from a few hundred to a few which were no longer commercially viable. So, they came to Gobabis to sell their cattle on auction and buy emergency feed, water, or accumulate financial reserves” (M.S., 23/01/2020).

Despite the lure of formal sector salaries and wages, almost a quarter (23.6%, n = 87) of household survey respondents derived their income from working in the informal economy (e.g. small business traders, construction, security guards, domestic workers, taxi drivers). Nonetheless, labour force surveys do not adequately capture the informal economy, and so it is likely that nationally derived figures underestimate the income earning opportunities in peri-urban and urban areas. A sizeable percentage (37%, n = 121) of respondents were also unemployed, indicating that the promise of new income opportunities is not always realised. Additionally, income benefits are not equally realised across genders; in the case of women migrants, their earning potential is less than that of men (USD 144.12 ± 11 vs. USD 195.71 ± 15.05 per month).

In the face of growing water insecurity, climate migration releases the burden of time spent collecting water and the need to walk further for wells and boreholes during droughts. Differential access between regions is shown in Online Resource 5 Fig. S9, where between 2001 and 2011, ≥ 50% households in the central region had access to safe water in the form of treated piped water inside their dwellings. However, in the north central region, most areas did not, except for the Oshana region. Another benefit for migrants is the water supply in the central region that is more secure than in the north central region. Khomas and Otjozondjupa regions are supplied with water from a three-dam system. Omatako, Swakoppoort, and Von Bach dams, supplemented by water from Kombat and Berg Aukas Mines, boreholes, and a reclamation plant, whereas the north central region is supplied by the Calueque dam and the Olushandja dam (Online Resource 5 Fig. S10).

Climate migration to urban centres is considered to allow better access to education and healthcare. Whilst perceptions of better education services are high, we found migrants in peri-urban areas who remain poorly educated: 12.4% (n = 41) of the sample had no access to schooling, while 31.5% (n = 105) had only primary level education. From a healthcare perspective, our analysis of the 2016 intercensal demographic report showed that 33% of households in Namibia are < 1 km to the nearest hospital or clinic and 32% between 2 and 5 km. Urban households travel shorter distances to get to hospitals; 48% are within 1 km compared to 15% for rural households. Deprivations in rural areas, such as poverty, malnutrition, unsafe sanitation and hygiene, and limited access to health facilities, are amplified by climate hazard impacts such as flood-related breakdown of infrastructure and post-disaster waterborne diseases outbreaks like cholera, hepatitis E, polio, and meningococcal disease. However, only 1.5% (n = 5) of household respondents had flushing toilet facilities inside or close to their homes, and due to dependence on shallow pit latrines, water-related and vector-borne diseases in peri-urban settlements are common. Moreover, as a group of residents noted: “A lot of people use valley for the toilet because the public toilets been broken for so many years. When it rains, in the lower areas the water is contaminated, and after it rains, the riverbed smells”. Despite this, 60% (n = 200) of respondents in the household survey regarded Windhoek’s treatment and sewerage systems as well functioning.

Conversations with various key informants suggested that migration offers the possibility of better access to affordable energy and that in urban centres, access to electricity supports adaptation directly through mechanised cooling or indirectly through allowing people longer days to be educated and earn income. Our analysis of the 1991, 2001, and 2011 Namibia Population and Housing Census supports this, in that there is still a reliance on charcoal and wood in the north central regions, compared to electricity in the central regions (Online Resource 6 Figure S11). Nevertheless, we found that in peri-urban settlements, 97.9% (n = 326) of household survey respondents did not have formal access to electricity, acknowledging that there may be regular illegal tapping of energy supplies. One plausible explanation for this is that most residents living in makeshift housing constructed without planning or building codes are explicitly denied the ability to upgrade or invest in housing due to a lack of tenure; 98.5% (n = 328) of household respondents had illegally settled on the land.

From the perspective of the communities of origin

Analysis of the national remittance statistics showed an exponential increase in received remittances at the national scale in the last three decades, and this decadal increase was highly significant (df = 2, F = 37.961, P = 1.4270 × 10−8) (Fig. 5). It is likely that these sources of income help communities of origin to buttress livelihood losses, stabilise income, and fund basic living needs such as food, education, consumer goods, and home improvements. When comparing cash remittances as a source of household income, the Oshana region had the highest level of remittances, and Otjozondjupa had the lowest, but this difference across regions not significant (df = 5, F = 1.178, P = 0.343), and ranged between 1.9 and 16.9% of household income between 2001 and 2018.

National remittance data. Yearly value of personal remittances paid and received (orange and blue lines), at the national scale, between 1990 and 2019. Personally received remittances increased substantially from USD 13.56 ± 1.84 million (SD) in 1990–1999, to USD 19.13 ± 20.46 million in 2000–2009, to USD 63.90 ± 13.39 million in 2010–2019. Paid remittances also increased from USD 14.81 ± 5.61 million in 1990–1999, to USD 22.01 ± 18.93 million in 2000–2009, to USD 80.87 ± 27.34 million in 2010–2019. The main graph also depicts the annual fluctuation in the value of remittances received compared to the previous year (grey bars) during the same period. The smaller inset graph displays the summative decadal value of remittances received

In addition to cash remittances, climate migration facilitates the exchange of non-marketed products from urban to rural communities and vice versa. Respondents described that in response to climate shocks, urban relatives send construction materials, clothes, or medicine to rural areas. This suggests that migration serves as a meaningful developmental opportunity for the community of origin when links are maintained. Indeed, communities may also retain strong cultural connections to their community of origin, as an NGO representative explained: “The Aawambo people residing in Windhoek, always say we are from the north. So, there is always that link, we don’t permanently move. We come back when we are retired or when we are about to finish our contract on Earth. People feel comfortable there, it is our land, and the soil is fertile” (R.K., 06/02/2020).

Nonetheless, there are negative consequences of climate migration for communities of origin. Communities of origin often experience a shortage of labour or skills due to high out-migration, resulting in a human capital deficit. At the same time, climate migration can have gendered impacts too. Key informant respondents indicated that the out-migration of men can cause a redistribution of household labour and increase demands on women in the short term, who engage not only on on-farm labour but often set up community development initiatives such as early childhood development centres.

From the perspective of the communities of destination

Rural resource flows increase urban climate resilience and reduce vulnerabilities, especially in relation to urban food security. Key informant interviews revealed that those residing in peri-urban settlements clearly regard their rural communities and households as important sources of food security, which is a primary benefit of strong social familial ties. Northern regions of Namibia supply peri-urban residents with products such as cereals (e.g. pearl millet (mahangu)), cassava, meat, poultry, dairy products, tubers, and other food supplies that do not need to be refrigerated. At the same time, food and non-food products from rural areas can be sold in urban markets, products such as medicinal plants (e.g. devil’s thorn, buffalo thorn), livestock, veld products, forest products (fuelwood), artisanal crafts (e.g. makalani nuts), as well as tree seeds (e.g. marula, wild date, mulberry, baobab, camelthorn, sweet thorn, moringa). The financial benefits derived from these products can be particularly welcome sources of income during inflationary periods, which often coincide with drought periods, because rural populations typically sell commodities at lower prices than imported alternatives. Beyond commodities, migrants offer human capital for instance in the form of skills, knowledge, and experience to help drive community development and labour and expertise to develop infrastructure.

On the other hand, climate migration—whilst benefiting an individual or household—can contribute to unplanned urban growth, proving a challenge to the community of destination. As a representative of the municipality described: “It’s illegal to put up the shacks. Some people are doing it during the weekend while the municipal officers are not working. So, when you wake up in the Monday, he [the informal settlement dweller] is already sleeping and cooking nice food (R.K., 09/02/2020)”. This can lead to conflict, competition, and tension in peri-urban settlements. Land settlement also puts pressure on municipal budgets, as the same senior official went on to explain: “If people settle on the land, the more the informal settlements grow, bringing more cost and burden for the city council. We don’t generate any tax from the informal settlements, so if they are to expand, the more the challenge (R.K., 09/02/2020)”. Conflicts between newcomers and established residents can arise related to land delimitation, employment, infrastructure, or overcrowding. For example, as a female councillor noted, “People who came illegally cleared the land and vandalised the toilets (S.H., 31/12/2018)”. A female leader of Okahandja Park in Windhoek went on to explain: “Changes happen when the informal settlement gets more crammed or more than one family lives on the same piece of land. Sometimes the municipality puts up numbers when the people erect an additional house which shouldn’t be designated as such. The municipality rarely calls meetings with the people who have cleared the land. In response, we have set up a women council to work with other leaders to keep the peace and order in the community, reduce domestic violence, and support police to fight against crime” (S.S., 04/01/2019)”.

Discussion

Growing climate hazards, changing livelihoods and climate migration

Overall, our findings reveal a growth in climate-related disasters (especially droughts and floods), which are more frequent in northern regions of Namibia. This pattern mirrors our broader analysis of climate-related disasters across sub-Saharan Africa (Online Resource 7 Fig. S12 to S14). This growth in hazards is in line with continental-wide modelled predictions (WMO 2020) and the expected future trajectories of temperature and rainfall patterns across Southern Africa (Trisos et al. 2022). Further analysis (World Bank 2021a, b) predicts growing irregular and intense seasonal rainfall and temperatures across Namibia, suggesting that more extreme periods of drought and flooding will be the dominant reality shaping Namibia’s future. The increased frequency of disasters has concomitant impacts on livelihoods—corroborated by previous studies (e.g. Amadhila et al. 2013; Anthonj et al. 2015; Heita 2018; Shikangalah 2020; Kapuka and Hlásny 2020). Meanwhile, global earth observation data of vegetation cover indicates the growing influence of drought, which negatively impacts agricultural productivity and pastoral livelihoods (FAO 2020). At the same time, migration flows are predominantly southerly towards the central regions of Khomas and Erongo, while most of the north central regions are seeing a net outflow of migrants. Considering the benefits and dis-benefits of climate migration, we suggest that exposure to climate-related hazards in the rural northern central regions contributes to enhancing out-migration, with more intense and extreme flooding and drought showing the strongest impacts.

Rural migration to peri-urban settlements

Aligning with other studies (Mastrorillo et al. 2016; Mueller et al. 2020), we found evidence that climate change is increasingly transforming pastoral and agricultural communities, with people mobilising towards urban centres and in particular peri-urban settlements. The benefits they seek for moving would, under normal circumstances, motivate rural–urban migration or act as pull factors. Yet, the vagaries of the climate and the impacts on livelihood sustainability in Namibia’s rural areas have increased the number of people moving or considering moving. Perhaps unsurprisingly, migrants suggest that migration to peri-urban destinations is driven by structural factors such as the perceived prospect of elevated socio-economic opportunities. This reinforces the significance of interactions between climate and non-environmental factors, as push and pull drivers, and lends further support to the environmental migration-development nexus paradigm (Neumann and Hilderink 2015). Birkmann et al. (2022) clearly indicates that climate hazards are driving rural income diversification, which is mainly supported through migration, urban wages, and remittances (Birkmann et al. 2022). This corresponds to findings revealed in the NHIES report (NSA 2016a, b, 2017) that shows that in urban centres, 72% of the households’ main source of income are wages and salaries compared to only 31.8% in rural areas. This further resonates with Mendelsohn et al. (2006) who suggest an apparent transition away from agricultural and livestock-based livelihoods in rural Namibia.

In peri-urban environments, migrants frequently work in the informal economy due to structural constraints such as labour market barriers, requirements to have a formalised address to access to social welfare, or a lack of official permission to live in the city (Dodman et al. 2017). However, livelihood strategies of migrants are not necessarily mutually exclusive, as many population groups’ livelihoods comprise a mix of complementary activities, such as petty trading, artisanal work, and the receipt of goods for sale or household consumption from rural family members (Wiederkehr et al. 2018). Therefore, a more diversified livelihood portfolio in general is conducive to a higher climate adaptation capacity due to the spreading of risk (e.g. Heita 2018). Migration also enhances adaptation through the creation of social networks amongst migrants and between communities, by facilitating the exchange of non-marketed products (Frayne 2007) as well as the transfer of resources, knowledge, technology, and capacities to help communities deal with environmental changes (Gemenne and Blocher 2017). Moreover, migrants also exchange food commodities with rural origins (Crush and Caesar 2018).

Importantly, the impacts that climate change has differs amongst migrant groups. People that seem to be most affected are those living in communal areas of (semi)permanent cropland, school children, or pastoralists lacking income to supplement fodder supplies during floods or droughts. Higher vulnerability to climate variability and change makes these groups more likely to use migration as an adaptation strategy. Climate change may act as a push factor whilst also reinforcing structural pull factors to impel economic transitions amongst the poorest, hastening shifts between agricultural labour and wages to other forms of labour (Birkmann et al. 2022). However, the youth and those with capital may be more likely to move, while women with more caring responsibilities and less negotiation power in some traditional areas may be less inclined to migrate. Previous studies in Zambia (Nawrotzki and DeWaard 2018; Mastrorillo et al. 2016) describe a similar phenomenon of trapped populations, where deep and persistent poverty results in negative feedback in the further erosion of already fragile economic livelihoods under climate change. Weinreb et al. (2020) in a study of 41 sub-Saharan African countries also describe how young adults were more likely to out-migrate from rural areas than children or the elderly—who are the most vulnerable that cannot afford migration as an adaptation strategy.

Connectivity across the rural–urban continuum supports adaptation

Baffoe et al. (2021) state: “while significantly influencing the creation of wealth, welfare, and employment, urban–rural linkages are also critical for improving regional governance and the competitiveness of related sectors and regions” (pp. 1342). We find that migration as an adaptation strategy is supported by deeply embedded linkages between rural and peri-urban areas. In a model of circular migration, rural–urban-rural, the rural and the urban are interdependent aspects of the same phenomenon (Steinbrink and Niedenführ 2020). This represents a form of trans-local optimisation, where climate migration between places provides for the most favourable outcome. In the future, these linkages will likely become more important, given growing urban unemployment and entry barriers to the formal economy (Frayne 2007; Mueller et al. 2020; Steinbrink and Niedenführ 2020) and increasingly felt impacts of climate change (Rigaud et al. 2018; Clement et al. 2021). Even when people living in urban centres are nominally poorer (e.g. less income), they may live more affluent lives (i.e. food supplies, reserves) compared to living in the north central region because of those dynamic social linkages that increase adaptivity (Tvedten 2008).

The downsides of climate migration as an adaptation strategy

Nevertheless, climate migration as an adaptive strategy also has dis-benefits. For migrants, peri-urban areas can be locations of heightened climate risks with concomitant health impacts (Borg et al. 2021), in which one configuration of risks in rural areas (e.g. heat stress) is merely replaced with another (e.g. flash flooding). Meanwhile, many migrants are inhibited in their ability to invest in land which complicates access to infrastructure and services (Dodman et al. 2017; Satterthwaite et al. 2020). For communities of origin, migration may amplify rural women’s vulnerability due to reduced labour power, as shown by Djoudi and Brockhaus (2011) in their work in Northern Mali and Lama et al. (2021). For the communities of destination, conditions in peri-urban informal settlements can become overburdened and infrastructure overstretched—impacting access to water, sanitation, health (Niva et al. 2019), and educational resources (Frayne 2004), while limiting livelihood opportunities to primarily trade (Mwilima 2006). This can lead to conflict, as shown by Oels (2011), who found that migrants are often used as scapegoats for other structural issues, reinforcing common misconceptions.

A limited picture but opening a conversation to extend current work

The extent to which we can fully untangle the interdependencies between climate and non-climate factors across the rural–urban continuum from this study is necessarily limited. First, secondary data are inherently limited by availability, accessibility, resolution, and comprehensiveness. Second, household survey data considered only peri-urban households. Third, migrants’ perceptions of environmental change do not always match observed changes in environmental parameters such as rainfall patterns as shown in Burkina Faso (de Longueville et al. 2020). Meanwhile, sometimes migrants inaccurately represent or are unaware of the impact of migration on their community of origin and tend to idealise the community of origin as the ‘rural homestead’ (Gemenne and Blocher 2017).

Nevertheless, there are several avenues that could be pursued to deepen and extend the present work. First, building on existing research examining the networked structure of migration (Bilecen and Lubbers 2021) that utilises social network analysis and cultural sociology, future empirical work could trace individuals throughout their climate migration journey, exploring the characteristics of places and what traps or immobilises populations, and how climate anomalies experienced at the destination influence migrant labour demand. Second, drawing on the work of authors such as Naudé and Bezuidenhout (2014), Couharde and Generoso (2015), and Crush and Caesar (2018), future research could focus on the interrelationships between climate migration, macroeconomic factors, and climate hazards and the role of remittances in supporting resilience. Third, mirroring research by Rigaud et al. (2021a, b) in West Africa and the Lake Victoria Basin, future work could extend the present household surveys and key informant interviews to other informal settlements and policy actors to explore strategic policy and planning development responses.

Conclusion

In this paper, we explored the growing phenomenon of rural-peri-urban climate migration and the evolving rural-peri-urban connections in post-independent Namibia. We document the possible benefits and dis-benefits of climate adaptation within the wider economic, socio-demographic, and geographic context. We adopted a regional perspective, focusing on north central and central regions of the country, and examined this issue using Lee’s (1966) three-part approach to migration, covering the migration continuum from origin, destination, and migrants’ perspectives, using primary and secondary data.

To return to the beginning, the issue of climate migration is not something that can be ignored, it is not only a fact but a lived reality for many millions of people, a true grand challenge. How we come together to make decisions, across all levels of policy and governance, will be critical in determining the impacts of climate change on migrant households and those left behind across the rural-peri-urban continuum. Lack of action, or indeed inappropriate action, will reduce the capacity to support climate-resilient investments to improve lives and livelihoods. As Clement et al. (2021) argue: “The trajectory of internal climate migration in the next half-century depends on our collective action on climate and development in the next few years. The window to avert the conditions that lead to distress-driven internal climate migration is shrinking rapidly” (pp. xix). Overall, climate migration as an adaptation strategy is increasingly central to sustainability agendas in developing countries (e.g. 2030 Agendas, Paris Agreement, Sendai Framework, New Urban Agenda) (Rigaud et al. 2018; Clement et al. 2021). The need for adaptation planning to better acknowledge climate migration and the embedded rural-peri-urban linkages that support livelihoods and to mitigate such risks is ever more urgent, as Rigaud et al. (2018) clearly state: “Many urban and peri-urban areas will need to prepare for an influx of people, including through improved housing and transportation infrastructure, social services, and employment opportunities. Policymakers can prepare by ensuring flexible social protection services and including migrants in planning and decision-making. If well managed, ‘in-migration’ can create positive momentum, including in urban areas which can benefit from agglomeration and economies of scale” (pp. xxii). Ultimately, successful climate migration—where benefits outweigh dis-benefits—will be based on the flows of goods and services through the rural-peri-urban–rural social network. Such networks will be central to enhancing resilience to both acute and chronic climate challenges that will be experienced across sub-Saharan Africa throughout the twenty-first century.

References

Adger WN, Safra de Campos R, ArdeyCodjoe SN, Siddiqui T, Hazra S et al (2021) Perceived environmental risks and insecurity reduce future migration intentions in hazardous migration source areas. One Earth 4(1):146–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2020.12.009

Afifi T (2011) Economic or environmental migration? The push factors in Niger. Int Migr 49:e95–e124. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2010.00644.x

Amadhila E, Shaamhula L, Van Rooy G, Siyambango N (2013) Disaster risk reduction in the Omusati and Oshana regions of Namibia. Jàmbá: J Disaster Risk Stud 5(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.4102/jamba.v5i1.65

Anderson KJ, Silva JA (2020) Weather-related influences on rural-to-urban migration: a spectrum of attribution in Beira. Mozambique Global Environ Change 65:102193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102193

Angula MN, Kaundjua MB (2016) The changing climate and human vulnerability in north central Namibia. Jàmbá: J Disaster Risk Stud 8(2). https://doi.org/10.4102/jamba.v8i2.200

Anthonj C, Nkongolo OT, Schmitz P, Hango JN, Kistemann T (2015) The impact of flooding on people living with HIV: a case study from the Ohangwena Region. Namibia Glob Health Action 8(1):26441. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v8.26441

Artur L, Hilhorst D (2012) Everyday realities of climate change adaptation in Mozambique. Global Environ Change 22(2):529–536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.11.013

Baffoe G, Zhou X, Moinuddin M, Somanje AN, Kuriyama A et al (2021) Urban–rural linkages: effective solutions for achieving sustainable development in Ghana from an SDG interlinkage perspective. Sustain Sci 16:1341–1362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-021-00929-8

Bilecen B, Lubbers MJ (2021) The networked character of migration and transnationalism. Glob Netw (oxf) 21:837–852. https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12317

Birkmann J, Liwenga E, Pandey R, Boyd E, Djalante R et al. (2022) Poverty, livelihoods and sustainable development. In: climate change 2022: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of working group II to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. In Pörtner H-O, Roberts DC, Tignor M, Poloczanska ES, Mintenbeck K, Alegría A, Craig M, Langsdorf S, Löschke S, Möller V, Okem A, Rama B. (Eds), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp 1171–1274. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844.010

Black R, Adger WN, Arnell NW, Dercon S, Geddes A et al (2011) The effect of environmental change on human migration. Global Environ Change 21:S3–S11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.10.001

Boas I, Farbotko C, Adams H, Sterly H, Bush S et al (2019) Climate migration myths. Nature. Clim Change 9(12):901–903. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-019-0640-4

Borderon M, Sakdapolrak P, Muttarak R, Kebede E, Pagogna R et al. (2018) A systematic review of empirical evidence on migration influenced by environmental change in Africa. IIASA Working Paper. Laxenburg, Austria: WP-18–003

Borg FH, Andersen JG, Karekezi C, Yonga G, Furu P et al (2021) Climate change and health in urban informal settlements in low- and middle-income countries – a scoping review of health impacts and adaptation strategies. Glob Health Action 14(1):1908064. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2021.1908064

Buchhorn M, Smets B, Bertels L, De Roo B, Lesiv, M, Tsendbazar N-E, Herold M, Fritz S (2020) Copernicus global land service: Land cover 100m: collection 3: epoch 2019: Globe available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/global/products/lc. Accessed 15 Nov 2020

Call M, Gray C (2020) Climate anomalies, land degradation, and rural out-migration in Uganda. Popul Environ 41:507–528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-020-00349-3

Central Bureau of Statistic (2004) Report on the annual agricultural surveys 1996-2003. Central Bureau of Statistics National PlanningCommission. Accessed 2 November 2022 from https://cms.my.na/assets/documents/Report_on_the_Annual_Agricultural_Surveys_1996_-_2003.pdf

Call MA, Gray C, Yunus M, Emch M (2017) Disruption, not displacement: environmental variability and temporary migration in Bangladesh. Global Environ Change 46:157–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.08.008

Cattaneo C, Beine M, Fröhlich C, Kniveton D, Martinez-Zarzoso I et al (2019) Human migration in the era of climate change. Rev Environ Econ Policy 13(2):1–19. https://doi.org/10.1093/reep/rez008

Clement V, Rigaud KK, de Sherbinin A, Jones B, Adamo S Schewe J, Sadiq N, Shabahat E (2021) Groundswell report. World bank, Washington, DC. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/3624

Conway D, van Garderen EA, Deryng D, Dorling S, Krueger T et al (2015) Climate and southern Africa’s water–energy–food nexus. Nat Clim Change 5:837–846. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2735

Couharde C, Davis J, Generoso R (2011) Do remittances reduce vulnerability to climate variability in West African Countries? Evidence from panel vector autoregression. Discussion paper 2. UNCTAD Special Unit for Commodities working paper series on commodities and development. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/suc-miscDP02_en.pdf. Accessed 1 Nov 2022

Couharde C, Generoso R (2015) The ambiguous role of remittances in West African countries facing climate variability. Environ Dev Econ 20(4):493–515. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X14000497

Crush JS, Caesar MS (2018) Food remittances and food security: a review. J Migr Dev 7(2):180–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/21632324.2017.1410977

Cundill GG, Singh C, Adger WN, Safra de Campos R, Vincent K et al (2021) Toward a climate mobilities research agenda: intersectionality, immobility, and policy responses. Glob Environ Change 69:102315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102315

de Longueville F, Ozer P, Gemenne F, Henry S, Mertz O, et al. (2020) Comparing climate change perceptions and meteorological data in rural West Africa to improve the understanding of household decisions to migrate. Clim Change 160:123–141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-020-02704-7

Delazeri LMM, Da Cunha DA, Rosa Oliveira LR (2021) Climate change and rural–urban migration in the Brazilian Northeast region. GeoJournal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-020-10349-3

Demographic Dividend Study Report (2018) Towards maximising the demographic dividend in Namibia pp. 1–96 from. https://namibia.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/Namibia_Demographic_Dividend_Study_Report_2018.pdf. Accessed 18 June 2021

Dennis M, Beesley L, Hardman M, James P (2020) Ecosystem (dis)benefits arising from formal and informal land-use in Manchester (UK); a case study of urban soil characteristics associated with local green space management. Agronomy 10:552

Dillon A, Mueller V, Salau S (2011) Migratory responses to agricultural risk in northern Nigeria. Am J Agric Econ 93:1048–1061. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aar033

Djoudi H, Brockhaus M (2011) Is adaptation to climate change gender neutral? Lessons from communities dependent on livestock and forests in northern Mali. Int for Rev 13(2):123–135. https://doi.org/10.1505/146554811797406606

Djurfeldt AA (2015) Urbanization and linkages to smallholder farming in sub-Saharan Africa: implications for food security. Glob Food Secur 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2014.08.002

Dodman D, Leck H, Rusca M, Colenbrander S (2017) African urbanisation and urbanism: implications for risk accumulation and reduction. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 26:7–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.06.029

EM-DAT (2020) EM-DAT | The international disasters database. Emdat.be. from. https://www.emdat.be/. Accessed 25 May 2021

Falco C, Galeotti M, Olper A (2019) Climate change and migration: is agriculture the main channel? Global Environ. Change 59:1–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.101995

FAO (2020) Global Information and Early Warning System 2017 Country Brief Namibia. Food and Agricultural Organisation, Rome

Frayne B (2004) Migration and urban survival strategies in Windhoek. Namibia Geoforum 35(489):505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2004.01.003

Frayne B (2007) Migration and the changing social economy of Windhoek, Namibia. Dev South Afr 24:91–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/03768350601165918

Gemenne F, Blocher J (2017) How can migration serve adaptation to climate change? Challenges to fleshing out a policy ideal. Geogr J 183(4):336–347. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12205

Grace K, Hertrich D, Singare D, Husak G (2018) Examining rural Sahelian out-migration in the context of climate change: an analysis of the linkages between rainfall and out-migration in two Malian villages from 1981–2009. World Dev 109:187–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.04.009

Gray C, Mueller V (2012) Drought and population mobility in rural Ethiopia. World Dev 40:124–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.05.023

Groth J, Hermans K, Wiederkehr C et al (2021) Investigating environment-related migration processes in Ethiopia – a participatory Bayesian network. Ecosyst People 17(1):128–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/26395916.2021.1895888

Heita J (2018) Assessing the evidence: migration, environment and climate change in Namibia. International Organization for Migration (IOM), Geneva, Switzerland

Henry S, Schoumaker B, Beauchemin C (2004) The impact of rainfall on the first out-migration: a multi-level event-history analysis in Burkina Faso. Popul Environ 25:423–460. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:POEN.0000036928.17696.e8

Hermans K, McLeman R (2021) Climate change, drought, land degradation and migration: exploring the linkages. Curr Opin in Environ Sustain 50:235–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2021.04.013

Hermans-Neumann K, Priess J, Herold M (2017) Human migration, climate variability, and land degradation: hotspots of socio-ecological pressure in Ethiopia. Reg Environ Change 17:1479–1492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-017-1108-6

Hirvonen K (2016) Temperature changes, household consumption, and internal migration: evidence from Tanzania. Am J Agric Econ 98(4):1230–1249. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aaw042

Hoffmann EM, Konerding V, Nautiyal S, Buerkert A (2019) Is the push-pull paradigm useful to explain rural-urban migration? A case study in Uttarakhand, India. Plos ONE 14(4):e0214511. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214511

Humavindu MN, Stage J (2013) Key sectors of the Namibian economy. J Econ Struct 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-2409-2-1

Hummel D (2016) Climate change, land degradation and migration in Mali and Senegal–some policy implications. J Migr Dev 5:211–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/21632324.2015.1022972

Hutchings P, Willcock S, Lynch K, Bundhoo D, Brewer T et al (2022) Understanding rural-urban transitions in the Global South through peri-urban turbulence. Nat Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-022-00920-w

International Organization for Migration (IOM) (2016) Migration in Namibia 2015: a country profile. IOM. Geneva, Switzerland

IOM (2020) Continental strategy for Africa 2020–2024. IOM. Geneva, Switzerland

IOM (2021) Institutional strategy on migration, environment and climate change 2021–2030 for a comprehensive, evidence and rights-based approach to migration in the context of environmental degradation, climate change and disasters, for the benefit of migrants and societies. International Organisation for Migration, Geneva, Switzerland

Kapuka A, Hlásny T (2020) Social vulnerability to natural hazards in Namibia: a district-based analysis. Sustainability 12:4910

Lama P, Hamza M, Wester M (2021) Gendered dimensions of migration in relation to climate change. Clim Dev 13(4):326–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2020.1772708

Lázár AN, Nicholls RJ, Hall JW, Barbour EJ, Haque A (2020) Contrasting development trajectories for coastal Bangladesh to the end of century. Reg Environ Change 20:93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-020-01681-y

Lee E (1966) A theory of migration. Duke University Press. Demography 3(1):47–57. https://doi.org/10.2307/2060063

Lewin P, Fisher M, Weber B (2012) Do rainfall conditions push or pull rural migrations? Evidence from Malawi. Agric Econ 43:191–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0862.2011.00576.x

Mabhaudhi T, Nhamo L, Mpandeli S, Nhemachena C, Senzanje A et al (2019) The water–energy–food nexus as a tool to transform rural livelihoods and well-being in Southern Africa. Int J Environ Res 16(6):2970. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16162970

MacGregor M (2010) ‘Gender and climate change’: from impacts to discourses. J Indian Ocean Reg 6(2):223–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/19480881.2010.536669

Marchiori L, Maystadt JF, Schumacher I (2012) The impact of weather anomalies on migration in sub-Saharan Africa. J Environ Econ Manage 63(3):355–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2012.02.001

Mastrorillo M, Licker B, Bohra-Mishra P, Fagiolo G, Estes L et al (2016) The influence of climate variability on internal migration flows in South Africa. Global Environ Change 39:155–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.04.014

Mbidzo M, Newing H, Thorn JPR,Can (2021) Nationally prescribed institutional arrangements enable community based conservation? An analysis of conservancies and community forests in the Zambezi Region of Namibia. Sustainability 13:10663. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910663

McCubbin S, Smit B, Pearce T (2015) Where does climate fit? Vulnerability to climate change in the context of multiple stressors in Funafuti. Tuvalu Global Environ Change 30:43–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.10.007

Mendelsohn J, el Obeid S, de Klerk N, Vigne P (2006) Farming systems in Namibia. Raison. Windhoek, Namibia. Available online:http://the-eis.com/elibrary/sites/default/files/downloads/literature/Farming%20systems%20in%20Namibia%20Part%201.pdf. Accessed 1 Nov 2022

Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Forestry (2018) 2016 Agricultural Statistics Bulletin. Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Forestry, Namibia

Morrissey JW (2013) Understanding the relationship between environmental change and migration: the development of an effects framework based on the case of northern Ethiopia. Glob Environ Change 23(6):1501–1510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.07.021

Mpandeli S, Naidoo D, Mabhaudhi T, Nhemachena C, Nhamo L et al (2018) Climate change adaptation through the water-energy-food nexus in Southern Africa. Int J Environ Res 15(10):2306. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15102306

Mueller V, Sheriff G, Dou X, Gray C (2020) Temporary migration and climate variation in eastern Africa. World Dev 126:104704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104704

Muñoz-Moreno M de L, Crawford MH (Eds.) (2021) Human migration: Biocultural perspectives. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press Inc. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190945961.001.0001

Mwilima N (2006) Informal trade in Namibia: opportunities for trade union intervention. Labour Resource and Research Institute. Available online: https://streetnet.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/namibiareport.pdf. Accessed 1 Nov 2022

Mycoo M, Wairiu M, Campbell D, Duvat V, Golbuu Y et al. (2022) Small islands. In: climate change 2022: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of working group II to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. In Pörtner H-O, Roberts DC, Tignor M, Poloczanska ES, Mintenbeck K, Alegría A, Craig M, Langsdorf S, Löschke S, Möller V, Okem A, Rama B. (Eds), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp 2043–2121. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844.017

Namibian Statistical Agency (2017) Namibia inter-censal demographic survey 2016 report. Namibian statistical agency, Windoek, Namibia

NamPower (2020) Nampower annual report 2020. NamPower: Windhoek, Namibia. Available online https://www.nampower.com.na/public/docs/annualreports/NamPower%20Annual%20Report%202020.pdf. Accessed 14 Nov 2022

NASA STRM (2015) Shuttle radar topographical mission available online: https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/. Accessed Nov 2020

Naudé WA, Bezuidenhout H (2014) Migrant remittances provide resilience against disasters in Africa. Atl Econ J 42:79–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-014-9403-9

Nawrotzki R, DeWaard J (2018) Putting trapped populations into place: climate change and inter-district migration flows in Zambia. Reg Environ Change 18(2):533–546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-017-1224-3

Nébié E, West C (2019) Migration and land-use and land-cover change in Burkina Faso: a comparative case study. J Political Ecol 26(1). https://doi.org/10.2458/v26i1.23070

Neumann K, Hilderink H (2015) Opportunities and challenges for investigating the environment-migration nexus. Hum Ecol 43:309–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-015-9733-5

Neumann K, Sietz D, Hilderink H, Janssen P, Kok M, van Dijk H (2015) Environmental drivers of human migration in drylands–A spatial picture. Appl Geogr 56:116–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2014.11.021

Nhamo L, Ndlela B, Nhemachena C, Mabhaudhi T, Mpandeli S et al (2018) The water-energy-food nexus: climate risks and opportunities in Southern Africa. Water (switzerland) 10(5):567. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10050567