Abstract

In northeast Brazil, fight-against-drought and cope-with-drought have been identified as two different drought policy paradigms. This article aims to examine the persistence, coexistence, intertwining, and evolution of these drought policy paradigms by studying how they inform national policy responses in human-water systems. The questions guiding our research are what do the paradigms of fight-against-drought and cope-with-drought consist of and how did the competing paradigms develop over time? To address these, the research draws on a systematic analysis of policy documents, multiannual strategic plans from 2000 to 2020 (the most recently published), and interviews with key informants. This study found the paradigms evolved with the persistence of the fight-against-drought paradigm with incremental changes of the cope-with-drought. The coexistence of paradigms started in 2004 and was in 2016 that the persistence, coexistence and intertwining of both were established. We use two theories, Hall’s (1993) policy and Lindblom’s (1959, 1979) incrementalism for analyzing the influences drought policy paradigms in human-water systems. This study provides new insights to understand the role of ideas in policy processes empirically showing how drought policy paradigms gradually evolve influencing policy responses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Drought itself is not a climate disaster, it is a normal part of climate. Whether it becomes a disaster depends on its impact on local people and the environment, and their level of resilience. Drought impacts are different from other natural hazards such as floods, tropical storms, and earthquakes; their impacts are nonstructural and spread over large geographical areas and temporal scales (Wilhite et al. 2014). The drivers of drought are diverse; drought can be triggered by altered weather patterns, reduced soil moisture, climate change, excess water demand, or multiple drivers combined (Mishra and Singh 2010). Often, policymakers and other decision makers treat this complex phenomenon as a rare and random event, responding to drought events in different ways.

Anthropogenic effects on the environment play an important role in changing drought patterns due to land use, deforestation, and overexploitation of water resources triggered by diverse water uses, such as domestic, irrigation, industrial, agricultural, and power generation (Kreibich et al. 2016; van Loon et al. 2016). For instance, a study by Araújo et al. (2004) claimed that a scenario with investment in cash crop production and tourism would lead to water scarcity. Against this background, government investments were in this direction, and nowadays, it leads to overuse of water and conflicts over water distribution (Studart et al. 2021).

In Brazil, droughts affect in particular, but not exclusively, the semiarid northeast region, with major socio-economic and environmental impacts. Governmental regional development strategies were predominantly welfare policies and hydraulic investments based largely on augmenting the water supply to deal with drought impacts; this strategy is referred to as the fight-against-drought paradigm. After more than a hundred years of fighting strategies (~ 1880–1980), a new paradigm emerged, known as the cope-with-drought paradigm, defined as a livelihood that respects local knowledge and culture, using technologies and production strategies appropriate to the environmental and climatic context attempting to use its potential in a sustainable way to reduce socio-ecological vulnerabilities to drought (Silva 2007).

Research about drought impacts in northeast Brazil in different fields uses the term policy paradigms (da Silva 2003; Machado and Rovere 2017) without using the policy lens and the scope of the research field that studies the role of ideas in policy processes, known as ideational field. Some scholars argue that paradigms have changed (Campos 2014; Pérez-Marin et al. 2017; Nogueira 2017), without clearly indicating the nature of change (Hall 1993). To add knowledge to the ideational field, this research empirically show how drought policy paradigms gradually evolve, coexist, persist, and become intertwined influencing policy responses. The research questions guiding our study are a step forward in this direction: what do the paradigms of fight-against-drought and cope-with-drought consist of, and how did the competing paradigms develop over time?

Background: regional development in northeast Brazil

In northeast Brazil, records about devastating drought episodes originate from Jesuit missionaries; the first recorded narrative, by a Jesuit priest Fernão Cardim, dates back to 1583 (Campos 2015). The 1877–1879 drought period resulted in a widespread famine that forced three million people to migrate and killed an estimated 500,000 people in Ceará State, representing roughly half the state’s population (Smith 1879). This period is known as the great drought, after which the first policy responses to drought impacts were discussed and implemented.

The emperor nominated a committee of engineers to provide solutions to the drought problem. The recommendations were to build railroads so the population could access the coast and to construct water storage systems for supply and irrigation. The first major work undertaken by the Imperial Government was the construction of the Cedro Dam in Ceará, which started in 1884 and was finished in 1906, under a republican government. The Cedro dam is a milestone that represents the beginning of the planning and implementation of açudes (Portuguese for dams) in Brazil. Other government responses included post-disaster emergency actions with food distribution in the most vulnerable areas, creation of state-financed work for drought victims (e.g., dam construction, irrigation, and land preparation), and access to financial credit (Magalhães 1993).

In the early twentieth century, the hydraulic solution began to take shape as a permanent public policy strategy, guiding the prevailing thinking in the public sphere for nearly 60 years (Campos 2014). The idea that the drought problem in the northeast would be solved by increasing water supply was reinforced by the hydraulic mission approach ongoing worldwide since the nineteenth century, defined as “the strong belief that every drop of water flowing into the ocean is a waste and that the state should develop hydraulic infrastructure to capture as much water as possible for human use” (Wester 2008, p. 10). In addition to infrastructure, the period was marked by the creation of hydrocracies to meet the challenges of flood protection, hydropower production, and large-scale public irrigation (Molle et al. 2009).

Brazil followed this lead; other responses included the creation of drought bureaucracies. The Inspectorate of Works Against Droughts (IOCS in Portuguese) was the first public institution established to develop and implement solutions to drought problems. In 1909, the name changed to Federal Inspectorate for Works Against Drought (IFOCS), which in 1945 became National Department for Works Against Drought (DNOCS). The names of these institutions indicate how drought impacts could be addressed: works emphasizes that the problems could be addressed with engineering solutions, and against droughts treats the natural phenomenon as a problem that could be solved rather than managed (Mattos 2017).

Another response was the establishment of the Working Group for Northeast Development, whose objective was to identify the causes of northeastern underdevelopment when compared with the other Brazilian regions and to investigate possible solutions for this problem. In 1959, as an outcome of the working group discussions, the Northeast Development Agency (SUDENE) was established to support autonomy in the northeast, and the state started to develop more planned actions specifically for that region (Bursztyn 1984).

However, other actions besides dam construction are mentioned as hydrological solutions to fight drought; the second phase of investments focused on irrigation in the semiarid region (Livingstone and Assunção 1989). From 1960, economic incentives to increase the exportation of irrigated fruit strengthened irrigation practices (da Silva 2003). In the 1970s, government policies began to emphasize the implementation of centers for agricultural and livestock modernization and to invest in irrigated perimeters. These were areas delimited by the state to implement public irrigated agriculture projects with, in general, significant agricultural potential, characterized by fertile soils, presence of water, favorable climate, and an abundant labor force (Pontes et al. 2013).

The 1980s marked the emergence of another discourse: the cope-with-drought paradigm. The new approach brought alternatives based on sustainable development to the Brazilian semiarid. A number of events and practices are considered to have contributed to the logic of living with the semiaridFootnote 1: the National Conference of the Bishops of Brazil, the work of Brazilian Agricultural Research Company (Embrapa), the Alternative Technology Project Network, and the rural union movements’ efforts (Pereira 2016). These initiatives have in common the development and diffusion of alternative projects and technologies for living with drought, such as the construction of cisterns, small dams, wells, small irrigation systems, community posts, flour houses, community gardens, seed banks, small animal husbandry (goats, bees, fish, chickens, and ducks), and incentivizing agroecology.

One milestone was a document released by Embrapa and Brazilian Technical Assistance and Rural Extension Company (Embrater) in 1982, entitled Human Coexistence with Drought, suggesting the implementation of farming systems to ensure human coexistence with drought (Embrapa 1982). The idea was to implement farming systems that would allow coexistence with drought as an alternative to the emergency measures usually adopted.

Another milestone for the cope-with-drought paradigm occurred during the 1999 United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (COP3) held in Recife, northeastern Brazil. The Semiarid Articulation (ASA), a group of 50 NGOs, was responsible for the creation and development of the Cisterns Program, which is the iconic public policy that made the discussions around coexistence with the semi-arid central. On this event, they released the Declaration of the Semiarid, claiming that coexistence with the conditions in the Brazilian semiarid and, in particular, with droughts, was possible (da Silva 2003). At COP3, a window of opportunity opened and the group managed to get an audience with the Environment Minister, José Sarney Filho, to discuss a policy called One Million Cisterns, which was introduced on the policy agenda marginally, first as an experimental project in the Ministry of Environment (Costa et al. 2013).

Over time, this policy underwent several incremental changes. In 2003, the main achievement was the guarantee of a specific budget for the construction of cisterns in the General Budget of the Union that became a key component of Brazil’s Zero Hunger (Fome Zero) strategy (Costa et al. 2013). In 2013, Law No. 12.873/2013 was sanctioned, instituting the National Program to Promote Rainwater Harvesting and Other Social Technologies for Access to Water – Cisterns Program, to promote access to water for human and animal consumption and food production (Brasil 2013). In 2017, the program won second place as one of the world’s best policies in the International Policy for the Future Award 2017 of the German organization World Future Council in partnership with the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (Future Policy 2017).

Theoretical framework

Policy paradigms

For more than two decades, Hall’s (1993) policy paradigms concept has motivated fruitful debates and research and has contributed to the consolidation of what has come to be known as the ideational approach in political science. A growing number of studies have attempted to understand the influence of ideas in the policymaking process (Menahem 1998; Orenstein 2013; Hirvilammi and Helne 2014; Daigneault 2014a; Vij et al. 2018; Meckling and Allan 2020).

Hall offers a conceptualization of policy paradigms as an interpretative framework defined as “a framework of ideas and standards that specifies not only the goals of policy and the kind of instruments that can be used to attain them but also the very nature of the problems they are meant to be addressing” (Hall 1993, p. 279). Paradigms are comprised of ideas, but not every idea is considered a paradigm (Baumgartner 2014). Generally, policy paradigms include the basic ideas shared within a policy community (Daigneault 2014b), where the policy outcomes in a given policy domain will usually be consistent with prevailing ideas that are already politically feasible, practical, and desirable (Skogstad and Schmidt 2011).

Some theories seek to explain how ideas influence policy formulation and change. In the coalition advocacy framework (Jenkins-Smith and Sabatier 1994), an advocacy coalition is held together by its members’ shared beliefs about a policy issue (Cairney and Weible 2017). According to Surel (1998), Hall’s paradigms concept and the belief system proposed by Paul Sabatier are based on the same observation: abstract concepts define the scope of policy possibilities in a given societal context. The multiple-streams theory, built on Cohen et al.’s (1972) garbage can model, considers policy streams as relatively independent of political and problems streams, because alternative solutions and ideas available to address problems take longer to develop and, furthermore, existing ideas to address other objectives are used to address a newly raised issue (Cairney 2020).

Policy paradigms diverge scientifically about the possibilities of coexistence. Hall (1993) assumes one single, coherent policy paradigm that dominates a policy area, whereas others suggest the presence of several competing paradigms (Jenkins-Smith and Sabatier 1994; Skogstad and Schmidt 2011).

Hall’s (1993) perspective is influential in policy dynamics and related fields, having been supported and extended by a substantial body of research. However, it has also been criticized on a variety of grounds: the constraints (1) on rigorously examining ideas as they are vague or abstract, one can argue that the study object is not well defined (Berman 2013); (2) on defining causal mechanisms or relational statements (Berman 2001); (3) on a clear analytic distinction between a policy paradigm and existing policies (Daigneault 2014b).

On the third point, Daigneault (2014b) suggests separating paradigms and policies when studying the role of ideas in policymaking. He argues that scholars should devote attention to the ideas shared by policymakers and to the policies later adopted. We thus applied his four-dimensional framework (outlined below) to our data in order to assess the prevalence of cope-with-drought and fight-against-drought paradigms over time, from 2000 to the present.

-

(1)

Values, assumptions, and principles about the nature of reality, social justice, and the appropriate role of the state

-

(2)

Comprehension of the problem that requires public intervention

-

(3)

Ideas about which policy ends and objectives should be pursued

-

(4)

Ideas about appropriate policy “means” to achieve those ends (i.e., implementation principles, types of instruments, and settings)

Incrementalism

Lindblom (1959) proposes the incremental model, which involves a “policy of small steps” without drastic changes, defined as “continually building out from the current situations, step by step and by small degrees” (Lindblom 1959). In his view, when managers are dealing with complex problems, they abandon rationality and use the successive limited comparisons method, also called the branch model, broadly known as the incremental model. Lindblom argues that this model describes the real world of policy analysis better than the rational comprehensiveness model, which requires a complete and intangible understanding of the exact consequences of every choice.

The successive limited comparison method acknowledges that decision makers cannot ignore the values and interests involved in policy decisions. Every decision has underlying effects on other decisions (Lindblom 1959, 1979). One decision leads to another, which depends on a past or competing decision, which in turn influences future decisions. This complex relationship — in addition to the impossibility of knowing all alternatives given that all consequences cannot be anticipated — time limitations, and political environment pressures lead the administrator to choose within a process of successive approximations toward the desired objective. These choices are embedded in a framework where the variables are not always understood or controlled, and also influenced by other decision makers’ value judgments.

Drivers, modes, and types of policy change

In Hall’s (1993) seminal work on policy paradigms, he is interested in explaining the factors that must be present to promote a paradigm shift as much as those that must be present to induce stability. His research focuses on the ideas and paradigms that explain this change, focusing on understanding the nature of policy change. He concludes that policy change is constrained because ideas that support established ideas remain extremely relevant; however, in the presence of paradigmatic shifts, policies can be transformed, creating a new equilibrium and a profound rupture with the past.

Three orders of paradigm change explain the nature of policy change. The first two orders suggest an evolutionary development within a paradigm. First-order change includes changes in policy instruments, like routine adjustments to existing policies, and second-order change includes the replacement of one policy instrument with another, whereas third-order change is revolutionary, shifts the goals themselves, as one paradigm is replaced by another (Hall 1993).

Research methodology

Study design and data collection

This paper adopts an interpretative approach and employs a case study method to answer the research question. The research draws on a systematic analysis of policy documents, multiannual strategic plans, and interviews with key informants.

Multiannual plans (Plano Plurianual: PPA, in Portuguese) are the main instrument for medium-term governmental planning with principles defined in the federal constitution. The executive must submit for legislative approval a PPA establishing the guidelines, objectives, and goals of the federal public administration for capital expenses for 4 years. PPAs contain a presidential message explaining the overall strategies and priorities for the period; a list of programs, each one aiming to achieve a specific goal; and policy actions describing the main deliverables to society.

One advantage of using the PPAs as a data source is that it brings together the set of public policies from the most varied sectors with the possibility of promoting integration among them. The PPAs have national objectives that influence all regions and states; it is a means of identifying problems of social demand, of public choice, and of prioritizing public goods. However, one limitation of this data source is that it includes only federal plans and not state-level plans. We made this decision because most infrastructure investments and nationwide programs are financed from federal resources.

Another advantage is associated with their recurring nature, because, legally, the instrument has to be issued every 4 years. We choose to work with PPAs starting from 2000 to 2003 because the first PPAs were quite generic with declarations of intent and broad projects. From this period onwards, there was a change in the relationship between plan and budget with mid-term-based planning to guide allocative decisions. A limitation of our focus on PPAs is that we did not take into consideration other documents from specific ministries (e.g., former Ministry of National Integration) that might include other actions related to both paradigms, but we took this decision to maintain methodological consistency in the document comparisons over time.

We also conducted interviews to add robustness to the findings from the document analysis. The interviews were conducted online between July and November 2020 with four civil servants who have worked in the government dealing with the management of drought impacts and one with an academic expert on northeast Brazil development. One civil servant was a former Minister of National Integration, the second was a former agrarian development secretary of Ceará state, and the third was a state advisor of the technical assistance and rural extension company of Ceará with more than 20 years of experience in other positions related to drought management in the state. Finally, the other civil servant has played many roles at different governance levels of drought management, for instance, internationally representing Brazil in Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change to include the perspective of semiarid regions, nationally as a special advisor for Northeastern affairs, state-level as secretary of planning in Ceará. The academic expert has more than 30 years of research in the Brazilian semiarid region with an innovative thesis at the time about the practices of clientelism and paternalism in the semiarid region with a research trajectory focusing on the area of sustainable development and public policies in the semi-arid region.

Data analysis

Data analysis was carried out in five stages. First, we used an abductive reasoning approach to analyze 4697 pages of PPAs from 2000 to 2020, the most recently published one. Abductive reasoning, introduced by Peirce (1955), refers to a type of inference distinguished from induction and deduction, focused on finding explanations for observed facts. We used the existing understanding of the concepts of fight-against-drought and cope-with-drought as a starting point. According to the literature, the fight-against-drought paradigm is based on the rationale that hydraulic solutions like reservoirs, wells, water supply systems, dams, and irrigation projects can prevent water shortage (da Silva 2003; Machado and Rovere 2017). The cope-with-drought paradigm is characterized mainly by the expansion of small reservoirs to harvest rainwater, accompanied by training on water resources management and climate-smart agriculture (Lipper et al. 2014; Machado and Rovere 2017). From this deductive starting point, we investigated inductively what these paradigms consist of, by studying their dimensions according to public policy theory about policy paradigms. This allowed us to further analyze the persistence, coexistence, intertwining, and evolution of those drought policy paradigms on the basis of the policy responses documented in the PPAs. This again increased our understanding of the nature of both paradigms.

Later, using a abductive process, we examine how the data support existing theories or hypotheses and how the data may call for modifications in existing understanding (Kennedy 2018). In our research, this line of reasoning was used to understand how data from PPAs explained the persistence, coexistence, intertwining, and evolution of those drought policy paradigms and their influence on policy responses in human-water systems. It increased our understanding of the definitions of both paradigms.

Second, ATLAS.ti 9.0 software was used to organize and code the policy documents. Third, we coded the data to identify programs, policy actions, and pieces of text to learn more about the paradigms and their evolvement. During this stage, we determined whether they related to fighting against, or cope-with-drought. Our final definition of each paradigm is presented in Table 1 of the “Results” section.

The final coding was as follows: policy program name, multiannual plan period, cope, fight, neither — the action was coded as neither when the information was not related to either of the paradigms or there was insufficient information to determine a category, and both — to actions that could be interpreted as both paradigms.

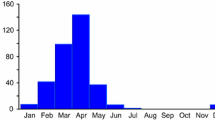

Fifth, to identify the persistence of each paradigm over time and to support our discussion about incremental changes and add a quantitative assessment, we counted the number of actions in each policy program related to the paradigms. We considered that each policy-program action related to a paradigm is evidence of the presence of actions related to that paradigm, revealing the persistence of each paradigm over time. For clarification, in the 2008–2011 period, the Water Infrastructure program had 182 policy actions, in which five were coded as a cope paradigm, 170 as a fight paradigm, 5 as neither, and 2 as both. In the 2012–2015 period, a similar type of program, Water Resources, had 112 policy actions, in which seven were coded as a cope paradigm, 43 as a fight paradigm, 36 as neither, and 27 as both. In Table 2, we present the policy programs in which we coded policy actions to develop Fig. 1.

In parallel with the document analysis, the interview-data analysis included the transcription of recorded interviews. After, we uploaded them to ATLAS.ti 9.0 to conduct the analysis also based on the ideas of both paradigms and their relation to the information presented in the PPAs.

Results

The results are presented in two sections. The first section answers the first part of our research question: what do the paradigms of fight-against-drought and cope-with-drought consist of, and the second section responds to the other part: and how did the competing paradigms develop over time?

Dimensions of drought paradigms in Brazil

This section describes the fight-against-drought and cope-with-drought dimensions. The paradigm dimensions are derived from Daigneault (2014b) as per Table 1. The policy paradigms are often criticized for being in the domain of ideas. With this table, we aim to provide a substantial definition of the paradigms discussed throughout the paper and approximate these concepts to the theory proposed by Hall (1993) and refined by Daigneault (2014b).

We define the fight-against-drought paradigm as the idea of nature domination, whereby conquering the environment with reservoirs could cease drought impacts. In this category, we classified programs and actions that prioritize the construction of açudes and hydraulic infrastructure (water basin transfers and channels) that transfers water from regions of greater availability to regions of scarcity. Other actions include relief measures such as cash transfers for municipalities under a state of emergency and water distribution by water trucks.

We define the cope-with-drought paradigm as a proactive attitude toward nature, seeking to adapt to the environmental and climatic context. In this category, we classified programs and actions that prioritize infrastructure that promotes the construction of small-dimension reservoirs, at the level of small farmers’ properties or, at most, dimensioned for common use by small groups of farmers or communities. Other actions include incentives to use climate-adapted seeds, agroecology, and the promotion of agricultural extension agents.

Interviewees had complementary views when asked about the changes in policy responses to drought over time. One participant mentioned that drought was seen as an inevitability, as a social problem, to which the main response was to help people who were hungry. There was also an idea of combat, fighting against nature with the idea of dominating nature, responses to which were based on hydraulic solutions to solve the water scarcity problem. Another view mentioned was that drought was seen as a problem of poverty, and later, the sustainable development idea emerged on the drought agenda. One interviewee commented that “we shall not fight with drought, let's understand that it exists and we will make a deal with drought and coexist with it”.

Competing paradigms in the multiannual plans

Here, we present a qualitative and quantitative assessment about how the paradigms have changed over time and how they have gradually become intertwined based on the programs and actions in the PPAs and supported by the interviews. In the period 2000–2003, fight-against-drought was dominant. All programs and their actions were related with this paradigm, except for the Waters of Brazil, which had an action for water desalinization in communities, which we consider to be a coping initiative as incentives to small-dimension water infrastructure for diffuse communities.

In 2004–2007, the fight-against-drought paradigm was still dominant, even though the expression, living with the semiarid, was introduced for the first time in an official government document. The drought in the northeast was highlighted as a problem in the presidential message. The plan was to tackle the problem with three major actions: (1) construct water infrastructure to supply cities and rural communities with water for humans and animals; (2) promote irrigation projects; and (3) coexist with the arid climate, i.e., train farmworkers in water harvesting practices on their properties to ensure drinking water and crop cultivation for human and animal consumption. The first evidence of coexistence occurs here with the program Integrated and Sustainable Development of the Semiarid; Conviver was a major policy named after the cope-with-drought paradigm but most of whose policy actions related to the fight-against-drought paradigm, for example implementation of water infrastructure works.

In 2008–2011, fight-against-drought was still dominant. Increased water supply would enable an equitable distribution of water, especially in the most critical regions like the northeast. The SFBIP was considered an outstanding project in this regard. The presidential message says, “[The SFBIP] will allow the perennialization of several natural and artificial water channels to supply the northeastern population”.

Three programs exclusively devoted to expanding infrastructure and water supply — Agriculture Development, Proágua Infrastructure, and Watershed Integration — were seen as a means toward regional development. Interestingly, for the first time, policy actions were associated with both paradigms, which we consider one evidence of intertwining. For example, human resource training for water infrastructure projects in the Water Resource program, we consider part of both paradigms as an action aiming to build awareness about the sustainable use of water resources for water infrastructure that was already in place.

In 2012–2015, fight-against-drought was still dominant. The presidential message acknowledged the uneven temporal and territorial distribution of water resources: “The North Region has 8% of the population, and accounts for 70% of the country's surface freshwater availability, whereas the other 30% has to meet 92% of the population”. To address this concern, two solutions related to the fight-against-drought paradigm were proposed: investments in water infrastructure projects to regulate flows, storing water from the rainy season to the dry season; water transfer from regions of greater availability to regions of scarcity. The construction of dams, channels, and adductor systems was expected to supply some municipalities. The SFBIP was again acknowledged because of its magnitude and scope. The coexistence is maintained with cope-with-drought paradigm emerging for the first time in a program typically related to the fight-against-drought paradigm, a program aiming to promote irrigated agriculture.

From 2016 to 2019, the fight-against-drought paradigm was dominant, but the cope-with-drought paradigm is gaining strength within various programs, many of which are typically oriented toward infrastructure construction. From this PPA onwards, the intertwining and coexistence become more visible. For instance, the program, Strengthening and Dynamizing Family Agriculture, had seven policy actions related to the cope-with-drought paradigm, to name a few: articulation for the development of solutions for the monitoring of family farming enterprises through technologies that use satellite images and agricultural-meteorological models, implementation of agro-meteorological models calibrated for northeastern Brazil to assess crop failure risks in semiarid municipalities, implementation of 90,000 social technologies of access to water for production, construction of boardwalk cisterns in the semiarid region, implementation of 98,000 technologies/systems of access to water for production.

While the cope-with-drought paradigm was gaining more strength, the impacts of the last greatest drought (2012–2018) were mentioned, “an intense water crisis has created a drought situation in specific regions of the country, leading to pressure on energy and food prices.” To respond to these events, the government invested in macroeconomic policies, infrastructure programs such as the Acceleration of Growth program, logistics, a housing program, tax breaks, and cheap credit to the private sector. Also, fiscal policy absorbed some of the energy-cost increase and financed specific actions to combat the effects of drought on the population directly affected.

In 2020–2023, both paradigms are equally dominant. The fight-against-drought paradigm is linked to the economics section. The water resource program will expand water supply in quantity and quality. Also included are an effective management of water resources and more construction of water infrastructures. The cope-with-drought paradigm is related to the food security program linked to the social section. This program aims to expand supply of, and access to, water and adequate and healthy food for socially vulnerable people, strengthening the SISAN.

On Table 2, we present some examples of actions present in the PPA’s and that have been coded, looking at actions means understanding what the main deliverables to society are. Our intention is not to offer an exhaustive list but to show the types of actions are included in the government programs.

Our quantitative assessment is used to identify the persistence of each paradigm over time. The Sankey diagram presents the extent of policy-action categories in the six PPAs and the incremental changes that occurred over 20 years (Fig. 1). It is accompanied by a cross-tabulation listing the categories, the number of occurrences, and the six multi-year plan periods (Table 3). It is composed of six main streams representing the total number of actions in each period and four streams representing the number of actions, varying in thickness according to the number of policy actions, and the categories to which these actions were coded.

Other evidence that supports the reasoning for understanding the persistence of each paradigm is the investments made in each program. The amount of moneyFootnote 2 invested in each program is also described in the PPAs. Investments in programs related to the fight-against-drought paradigm are higher in all years. For example, in the period 2008–2011, the Conviver program received $12,954,941.76, whereas the Water Infrastructure program received $576,081,890.80. Comparison shows that investments in water infrastructure were 40 times greater than investments in cope-with-drought.

Discussion

Building on two drought policy paradigms, fight-against-drought and cope-with-drought, we used policy paradigm and incrementalism theories to understand what drought paradigms consisted of and how they developed over time influencing the human-water systems at the local level.

The debates and definitions around the paradigms are extensive in the Portuguese language, for instance, in special issues in Brazilian Journals (Rozendo and Diniz 2020; Drummond and Bursztyn 2016). Some articles are published in English (Campos 2015; Pérez-Marin et al. 2017; Machado and Rovere 2017; Lindoso et al. 2018) and discuss the paradigms and their relation to the northeast development. Our intention was not to exhaust the possibilities of definitions but to provide an understanding of the paradigms by connecting them with the four dimensions of the policy paradigm lens.

This study has identified what the paradigms consisted of using the four policy paradigm dimensions. The fight-against-drought is delivered to society as actions prioritizing the construction of açudes and hydraulic infrastructure (water basin transfers and channels) that transfer water from regions of greater availability to regions of scarcity. Other actions include relief measures such as cash transfers for municipalities under a state of emergency and water distribution by water trucks. Yet, the cope-with-drought paradigm entails actions that prioritize infrastructure that promotes the construction of small-dimension reservoirs, at the level of small farmers’ properties or, at most, dimensioned for common use by small groups of farmers or communities. Other actions include incentives to use climate-adapted seeds, agroecology, and the promotion of agricultural extension agents.

Our results show the most common shared idea within the policy community was the fight-against-drought paradigm. The persistence of fight-against-drought is justified by programs exclusively dedicated to sustaining investments in water infrastructures in all years. The term “living with an arid climate” was explicitly mentioned in the 2004–2007 PPA as an attempt to include cope-with-drought in the plans; it emerged as an idea but was overshadowed by the fight-against-drought. It can thus be suggested that the government acknowledges both paradigms but the investments are mainly focused on the paradigm already in place.

We understand intertwining as the moments when the two paradigms become mutually involved and connected, for instance, programs and actions with initiatives encompassing both perspectives from 2008 onwards. This increase in cope-with-drought can be interpreted as incremental changes of one paradigm over the established one. One example is actions related to increasing the management investments in water infrastructure. This finding is consistent with the discussion about adaptation to drought impacts on two distinct measures: large reservoirs (hard path) and governance (soft path) (Medeiros and Sivapalan 2020).

The most interesting finding was that the food security component was responsible for strengthening the persistence of the cope-with-drought paradigm. Increasing water access was an important component of food security becoming part of the Hunger Zero Program, implemented in Brazil during Luiz Inácio’s administration in 2003. The coexistence of both paradigms can be seen in the role of the cisterns in strengthening the cope-with-drought paradigm mainly from 2012 onwards. These rain harvest reservoirs created new forms of access to water in rural areas of the semiarid region (Arsky 2020). It was mentioned by one interviewee that the cisterns are relevant for scattered populations as they reduce their vulnerability in remote areas where it is not possible to deliver piped water.

Studies show that a variety of policies have increased smallholder farmers’ resilience to external shocks in northeast Brazil. Cisterns optimize food production, management of common-pool resources, strengthen the social organization, provide access to public programs (Pérez-Marin et al. 2017), and promote farmers’ adaptive capacity through social learning (Cavalcante et al. 2020). Others are Program for the Promotion of Rural Productive Activities (Fomento, in Portuguese) (Mesquita et al. 2020) and Food Acquisition Program (PAA) (Mesquita & Milhorance 2019). The role of other policies to strengthen the cope-with-drought paradigm, such as the National Program to Strengthen Family Agriculture (PRONAF), a credit program that offers loans at a subsidized interest rate to family farmers, and Bolsa Família, a conditional cash transfer program, was mentioned by one interviewee. Next to national policies also state-level policies are relevant, such as Prorural, Pernambuco More Productive, and Productive Bahia a Pro-Semiarid which are discussed by Milhorance et al. (2020). Our study provides insights based on national policies, providing a first step to better understanding the implications of policy formulation and implementation at the local level. The discussion about state-level policies is beyond the scope of our study. The inclusion of these cope-with-drought policies would improve the model of typical dynamic patterns of smallholder development proposed by Sietz et al. (2006) in the late 1990s–early 2000s in the region.

The results for the period 2016–2019 clearly show the persistence, coexistence, and intertwining of the two paradigms; this is observed in the Sankey diagram. Interestingly, this PPA was published during an ongoing multi-year drought (2012–2018), which is considered the worst in recent decades (Dantas et al. 2020) and has proved devastating for some agricultural, livestock, and industrial producers (Gutiérrez et al. 2014). On this document, the government acknowledges the drought as a major driver of negative economic impacts. The incremental growths of the cope-with paradigm were sustained during this period, as the previous investments made in large infrastructure, especially between the 1990s and the early 2000s that were perceived as a definitive and effective response to drought impacts were proved as insufficient on this multi-year drought.

The lower number of actions in 2020–2023 is related to the administration of Jair Bolsonaro, which has been dismantling many policies in Brazil and the public administration structure. For this PPA specifically, the administration removed the submission of PPA-related investments in the current plan, and in addition to that, a constitutional amendment proposal was submitted to the congress in November 2019 that envisioned the elimination of the multiannual plans as an instrument for planning (Couto and Cardoso Junior 2020). The policy dismantling is occurring in many areas, including environmental, education, and family farming policies (Sabourin et al. 2020).

The evolution of paradigms is characterized, at most, as second order change based on Hall (1993), with some policy instruments replacing with another, not a paradigm shift as many authors argue (da Silva 2003; Campos 2015; Pérez-Marin et al. 2017; Machado and Rovere 2017). A second-order change suggests an evolutionary development within a paradigm; this is evident in this case, where we can see a process of gradual change between the paradigms with incremental changes strengthening the cope-with-drought paradigm. This paradigm was timidly emerging in official policy documents from 2004, but it was only between 2016 and 2019 that this paradigm gained more relevance, indicating the coexistence and persistence of both. A gradual change of paradigms was also found in a study of climate policy paradigms in Bangladesh (Vij et al. 2018).

It is more difficult for a paradigm shift to happen when the paradigm has been institutionalized and is managed by a solid policy network (Menahem 1998), which is the Brazilian case. Fight-against-drought was for a long time the dominant idea on dealing with drought impacts in Brazil. The first reservoirs were introduced under the Imperial Government, continued over time, and were strengthened by the hydraulic mission (Molle et al. 2009). In other words, an established paradigm like the fight-against-drought paradigm takes time to change.

Coleman et al. (1996) found that fundamental change comes slowly, preserves political stability, comes through the proper functioning of established institutions, and has low citizen involvement. The latter, in our research, is different: civil society involvement pushed the cope-with-drought paradigm onto the political agenda (Costa et al. 2013; Pereira 2016). Prior studies have noted the importance of the emergence of the cope-with-drought paradigm as a bottom-up governance strategy led by civil society (Machado and Rovere 2017), which influenced political debate through civil society and academic forums such as the Drought Forum (1989–1996) (Sieber and Gomes 2020) and the COP3 (da Silva 2003).

Conclusion

In this article, we examined the persistence, coexistence, intertwining, and evolution of drought policy paradigms and their influence on policy responses in human-water systems, guided by the following research questions: what do the paradigms of fight-against-drought and cope-with-drought consist of, and how did the competing paradigms develop over time?

In this article, we use two theories, Hall’s (1993) policy paradigms refined by Daigneault (2014b) and Lindblom’s (1959, 1979) incrementalism, to explain what these two paradigms consist of, and how they developed over time. This study found the paradigms evolved with the persistence of the fight-against-drought paradigm with incremental changes of the cope-with-drought. The first evidence of coexistence occurs 2004 when the cope-with-drought paradigm was introduced for the first time in an official government but never had a policy program fully dedicated to its strengths. The coexistence and intertwining persisted over time but was in 2016 that the persistence, coexistence, and intertwining of both were established. We attributed to the cisterns program the persistence of the cope-with-drought paradigm over time because water access was an important component of food security.

The dominance of fight-against-paradigm overtime is expected because it was institutionalized and managed by a solid policy network. The change of paradigms is characterized as second order change based on Hall (1993), with some policy instruments replaced with another, in this study translated as the increasing number of actions strengthening the cope-with-drought paradigm.

The analytical framework proposed in this study is grounded in a combined conceptual perspective linking policy paradigms with incrementalism. It offers a comprehensive combination of theories for analyzing the influences of existing paradigms in policy responses.

Notes

Alternative synonyms are used for the cope-with-drought idea: living with drought, human coexistence with drought, coexistence with the semiarid, and living with the semiarid.

Values are in American dollars, exchange rate: RS1.00 to $5.24 (May 28, 2021) does not take inflation into account.

References

Araújo JC, Döll P, Güntner A, Krol M, Abreu C et al (2004) Water scarcity under scenarios for global climate change and regional development in semiarid northeastern Brazil. Water Int 29:209–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060408691770

Arsky IDC (2020) Os efeitos do Programa Cisternas no acesso à água no semiárido. Desenvolv Meio Ambiente 55. https://doi.org/10.5380/dma.v55i0.73378

Baumgartner FR (2014) Ideas, paradigms and confusions. J Eur Publ Policy 21:475–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2013.876180

Berman S (2001) Ideas, norms, and culture in political analysis. Comparative Politics 33:231. https://doi.org/10.2307/422380

Berman S (2013) Ideational Theorizing in the Social Sciences since “policy paradigms, social learning, and the state”: ideational theorizing in political science. Governance 26:217–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12008

Brasil (2013) LEI No 12.873 - Programa Nacional de Apoio à Captação de Água de Chuva e Outras Tecnologias Sociais de Acesso à Água - Programa Cisternas

Bursztyn M (1984) O poder dos donos - Planejamento e Clientelismo no Nordeste. Vozes, Petrópolis

Cairney P (2020) Ideas and multiple streams analysis. Understanding Public Policy - Theories and Issues, 2nd edn. Red Globe Press University of Stirling, UK, pp 299–309

Cairney P, Weible CM (2017) The new policy sciences: combining the cognitive science of choice, multiple theories of context, and basic and applied analysis. Policy Sci 50:619–627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-017-9304-2

Campos JNB (2015) Paradigms and public policies on drought in northeast Brazil: a historical perspective. Environ Manage 55:1052–1063. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-015-0444-x

Campos JNB (2014) Secas e políticas públicas no semiárido: ideias, pensadores e períodos. Estud Av 28:65–88. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-40142014000300005

Cavalcante L, Mesquita PS, Rodrigues-Filho S (2020) 2nd water cisterns: social technologies promoting adaptive capacity to Brazilian family farmers. Desenvolv Meio Ambiente 55. https://doi.org/10.5380/dma.v55i0.73389

Cohen MD, March JG, Olsen JP (1972) A garbage can model of organizational choice. Adm Sci Q 17:1. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392088

Coleman WD, Skogstad GD, Atkinson MM (1996) Paradigm shifts and policy networks: cumulative change in agriculture. J Pub Pol 16:273–301. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X00007777

Costa A, Dias R (2013) Estado e sociedade civil na implantação de políticas de cisternas. In: Costa A (ed) Tecnologia Social e Políticas Públicas, São Paulo, Instituto Pólis; Brasília, Fundação Banco do Brasil, pp 33–63

Couto LF, Cardoso Junior JC (2020) A função dos planos plurianuais no direcionamento dos orçamentos anuais: avaliação da trajetória dos PPAs no cumprimento da sua missão constitucional e o lugar do PPA 2020–2023. Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada 66

da Silva RMA (2003) Entre dois paradigmas: combate à seca e convivência com o semi-árido. Sociedade e estado 18:361–385

Daigneault P-M (2014a) Three paradigms of social assistance. SAGE Open 4:215824401455902. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014559020

Daigneault P-M (2014b) Reassessing the concept of policy paradigm: aligning ontology and methodology in policy studies. J Eur Publ Policy 21:453–469. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2013.834071

Dantas JC, da Silva RM, Santos CAG (2020) Drought impacts, social organization, and public policies in northeastern Brazil: a case study of the upper Paraíba River basin. Environ Monit Assess 192:317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-020-8219-0

Drummond JA, Bursztyn M (Eds) (2016) Do combate à seca à convivência com o semiárido. Novos caminhos à procura da sustentabilidade [Edição Especial]. Sustentabilidade em Debate. Brasília, DF.

Embrapa E (1982) Semi-árido brasileiro: convivência do homem com a seca. Implantação de sistemas de exploração de propriedades agrícolas: uma proposta de ação. Brasília - DF

Future Policy (2017) Brazil’s Cisterns Programme. In: futurepolicy.org. https://www.futurepolicy.org/healthy-ecosystems/biodiversity-and-soil/brazil-cisterns-programme/. Accessed 12 May 2021

Gutiérrez APA, Engle NL, De Nys E, Molejón C, Martins ES (2014) Drought preparedness in Brazil. Weather and Climate Extremes 3:95–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wace.2013.12.001

Hall PA (1993) Policy paradigms, social learning, and the state: the case of economic policymaking in Britain. Comp Polit 25:275. https://doi.org/10.2307/422246

Hirvilammi T, Helne T (2014) Changing paradigms: a sketch for sustainable wellbeing and ecosocial policy. Sustainability 6:2160–2175. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6042160

Jenkins-Smith HC, Sabatier PA (1994) Evaluating the advocacy coalition framework. J Pub Pol 14:175–203. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X00007431

Kennedy B (2018) Deduction, induction, and abduction. In: Flick U (ed) The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection, SAGE Reference, Los Angeles, pp 49–64

Kreibich H, Krueger T, Van Loon A, Mejia A, Liu J et al (2016) Scientific debate of Panta Rhei research – how to advance our knowledge of changes in hydrology and society? Hydrol Sci J 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/02626667.2016.1209929

Lindblom CE (1959) The science of “muddling through.” Public Adm Rev 19:79–88. https://doi.org/10.2307/973677

Lindblom CE (1979) Still muddling, not yet through. Public Adm Rev 39:517–526. https://doi.org/10.2307/976178

Lindoso D, Eiró F, Bursztyn M, Rodrigues-Filho S, Nasuti S (2018) Harvesting water for living with drought: insights from the brazilian human coexistence with semi-aridity approach towards achieving the sustainable development goals. Sustainability 10:622. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030622

Lipper L, Thornton P, Campbell BM, Baedeker T, Braimoh A et al (2014) Climate-smart agriculture for food security. Nature Clim Change 4:1068–1072. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2437

Livingstone I, Assunção M (1989) Government policies towards drought and development in the Brazilian Sertao. Dev Chang 20:461–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.1989.tb00355.x

Machado L, Rovere E (2017) The traditional technological approach and social technologies in the Brazilian semiarid region. Sustainability 10:25. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010025

Magalhães, A (1993) Drought and Policy Responses in the Brazilian Northeast. In: Wilhite D (ed) Drought Assessment, Management, and Planning: Theory and Case Studies. Natural Resource Management and Policy, vol 2. Springer, Boston, pp 181–198

Mattos LC (2017) Um tempo entre secas: Superação de calamidades sociais provocadas pela seca através das ações em defesa da convivência com o semiárido. PhD Thesis, Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro

Meckling J, Allan BB (2020) The evolution of ideas in global climate policy. Nat Clim Chang 10:434–438. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0739-7

Medeiros P, Sivapalan M (2020) From hard-path to soft-path solutions: slow–fast dynamics of human adaptation to droughts in a water scarce environment. Hydrol Sci J 65:1803–1814. https://doi.org/10.1080/02626667.2020.1770258

Menahem G (1998) Policy paradigms, policy networks and water policy in Israel. J Pub Pol 18:283–310. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X98000142

Mesquita P, Folhes RT, Cavalcante L, Rodrigues LVN, Santos BA et al (2020) Impacts of the Fomento Program on Family Farmers in the Brazilian Semi-Arid and its relevance to climate change: a case study in the region of Sub medio São Francisco. SustDeb 11:211–225. https://doi.org/10.18472/SustDeb.v11n1.2020.30505

Mesquita P, Milhorance C (2019) Facing food security and climate change adaptation in semi-arid regions: lessons from the Brazilian Food Acquisition Program. SustDeb 10:30–42. https://doi.org/10.18472/SustDeb.v10n1.2019.23309

Milhorance C, Sabourinb E, Le Coq J-F, Mendes P (2020) Unpacking the policy mix of adaptation to climate change in Brazil’s semiarid region: enabling instruments and coordination mechanisms. Climate Policy 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2020.1753640

Mishra AK, Singh VP (2010) A review of drought concepts. J Hydrol 391:202–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2010.07.012

Molle F, Mollinga PP, Wester P (2009) Hydraulic bureaucracies and the hydraulic mission: flows of water, flows of power. Water Alternatives 2:328–349

Nogueira D (2017) Segurança hídrica, adaptação e gênero. SustDeb 8:22–36. https://doi.org/10.18472/SustDeb.v8n3.2017.26544

Orenstein MA (2013) Pension privatization: evolution of a paradigm: pension privatization: evolution of a paradigm. Governance 26:259–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12024

Peirce C (1955) Abduction and induction. Philosophical Writings of Peirce. Dover Publications Inc, New York, pp 150–156

Pereira, MC (2016) Água e convivência com o semiárido: múltiplas águas, distribuições e realidades. Dissertation, Fundação Getúlio Vargas, São Paulo

Pérez-Marin AM, Rogé P, Altieri MA, Forero LFU, Silveira S et al (2017) Agroecological and social transformations for coexistence with semi-aridity in Brazil. Sustainability 9:990. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9060990

Pontes AGV, Gadelha D, Freitas BMC, Rigotto RM, Ferreira MJ (2013) Os perímetros irrigados como estratégia geopolítica para o desenvolvimento do semiárido e suas implicações à saúde, ao trabalho e ao ambiente. Ciênc saúde coletiva 18:3213–3222. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232013001100012

Rozendo C, Diniz PCO (2020) Sociedade e ambiente no Semiárido: controvérsias e abordagens. Desenvolvimento e Meio Ambiente 55. https://doi.org/10.5380/dma.v55i0

Sabourin E, Craviotti C, Milhorance C (2020) The dismantling of family farming policies in Brazil and Argentina. irpp 2:45–67. https://doi.org/10.4000/irpp.799

Sieber SS, Gomes RA (2020) Do enfrentamento à convivência: o Fórum Seca como movimento político. Desenvolv Meio Ambiente 55. https://doi.org/10.5380/dma.v55i0.73864

Sietz D, Untied B, Walkenhorst O, Ludeke MKB, Mertins G et al (2006) Smallholder agriculture in Northeast Brazil: assessing heterogeneous human-environmental dynamics. Reg Environ Change 6:132–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-005-0010-9

Silva RMA (2007) Entre o Combate à Seca e a Convivência com o Semi-Árido: políticas públicas e transição paradigmática. Revista Econômica Do Nordeste 38:466–485

Skogstad G, Schmidt V (2011) Introduction: policy paradigms, transnationalism, and domestic politics. In: Skogstad (ed) Policy paradigms, transnationalism, and domestic politics. University of Toronto Press, Toronto, pp 3–35

Smith H (1879) Brazil, the amazons and the coast. Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York

Studart TM de C, Campos JNB, Souza Filho FA de, Pinheiro MIT, Barros LS (2021) Turbulent waters in Northeast Brazil: A typology of water governance-related conflicts. Environ Sci Policy 126:99–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.09.014

Surel Y (1998) Idées, intérêts, institutions dans l’analyse des politiques publiques. Pouvoirs 87:161–178

Van Loon AF, Stahl K, Di Baldassarre G, Clark J, Rangecroft S et al (2016) Drought in a human-modified world: reframing drought definitions, understanding, and analysis approaches. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 20:3631–3650. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-20-3631-2016

Vij S, Biesbroek R, Groot A, Termeer K (2018) Changing climate policy paradigms in Bangladesh and Nepal. Environ Sci Policy 81:77–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.12.010

Wester P (2008) Shedding the waters: institutional change and water control in the Lerma-Chapala basin. Wageningen University & Research, Mexico

Wilhite DA, Sivakumar MVK, Pulwarty R (2014) Managing drought risk in a changing climate: the role of national drought policy. Weather and Climate Extremes 3:4–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wace.2014.01.002

Acknowledgements

This work forms part of the project: “3DDD: Diagnosing drought for dealing with drought in 3D”, funded by the Dutch Research Council (NWO) under grant W07.30318.016.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Diana Sietz

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cavalcante, L., Dewulf, A. & van Oel, P. Fighting against, and coping with, drought in Brazil: two policy paradigms intertwined. Reg Environ Change 22, 111 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-022-01966-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-022-01966-4