Abstract

Promoting and increasing the uptake of sustainable agricultural practices poses a major challenge for European agricultural policy. The scientific evidence for potentially relevant and environmentally beneficial practices, however, is scattered among numerous sources. This article examines the state of knowledge regarding agri-environmental practices and their impact on various domains of the environment (climate change, soil, water and biodiversity). The selection was restricted to practices applicable to German farmers. Ninety-eight literature reviews and meta-analyses assessing the environmental impacts of agri-environmental practices in the German context were found in a systematic review of the academic literature from 2011 onwards. A total of 144 agricultural management practices were identified that contribute toward achieving certain environmental objectives. The practices were clustered in eight categories: (1) Fertilizer strategies, (2) Cultivation, (3) Planting: vegetation, landscape elements & other, (4) Grazing strategies, (5) Feeding strategies, (6) Stable management, (7) Other, (8) Combined practices & bundles. The findings of this study suggest that some general patterns can be observed regarding the environmental benefits of different practices. While it is possible to derive recommendations for specific practices in terms of individual environmental objectives, their relevance is likely to be context-dependent. Moreover, this study reveals that bundles of practices can have positive synergistic impacts on the environment. Notably, only few reviews and meta-analyses considered the implementation and opportunity costs of environmentally beneficial practices. Agri-environmental policies need to consider the broad range of practices that have been shown to impact the environment positively, including their costs, and provide context-specific incentives for farmers to adopt them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Promoting and increasing the uptake of sustainable agri-environmental practicesFootnote 1 is an urgent challenge for European agricultural policy. Since the turn of the millennium, the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) of the European Union has striven not only to support agricultural production but also to incorporate nature and environmental protection by setting up multiannual incentive schemes designed to increase the adoption of agri-environmental practices. These agri-environmental measures compensate farmers for voluntary environmental commitments (Lefebvre et al. 2020). In addition to being incorporated within the CAP, numerous agri-environmental practices are also included in other guidelines, strategies, directives and regulations (e.g. EU Eco-Regulation, Germany’s National Sustainable Development Strategy, Ackerbaustrategie 2021). However, the current agri-environmental policies and practices being pursued are not sufficient for protecting the environment; agriculture is still a major cause for the Earth system exceeding planetary boundaries and is the main driver of environmental degradation in Europe (Campbell et al. 2017; Pe’er et al. 2020). In Germany, for example about 7.5% of annual greenhouse gas emissions are attributable to agriculture. Furthermore, agricultural intensification has led to a widespread decline in arthropod biomass and the abundance and number of species as well as to the degradation of soils and the pollution of water bodies (Dörschner and Musshoff, 2015; Seibold et al. 2019; Visconti et al. 2018). This trend is unlikely to change in the near future, as the CAP is currently failing to achieve its environmental objectives (Pe’er et al. 2019). There are various reasons for the inadequacy of agri-environmental practices in Germany when it comes to protecting the environment. One is that CAP practices aimed at German farmers are based on regionally adapted catalogues which farmers feel are not flexible enough in terms of local conditions; indeed, they are sometimes even perceived as being incompatible with good professional practice (Wittstock et al. 2022). Moreover, most CAP measures are “action-based” payments, meaning that farmers receive a uniform payment for adopting a specific agri-environmental practice, rather than result-based schemes, meaning that the effects of measures are not monitored (Bartkowski et al. 2021).

The relationship between agricultural production and the environment is complex and multi-facetted. Fundamentally, agricultural production depends on a well-functioning environment, and yet farmers are currently contributing to the degradation of ecosystems (Seppelt et al. 2020). For instance, agricultural emissions of greenhouse gases contribute substantially to global warming (Clark et al. 2020; Wójcik-Gront, 2020), which in turn increases the magnitude, frequency and duration of extreme weather events such as droughts (Hari et al. 2020; Samaniego et al. 2018) and (flash) floods (Fowler et al. 2021). Both droughts and floods affect farmers negatively by causing losses of yield (Borrelli et al. 2020; Webber et al. 2020). The interests of both farmers and the public have synergistic effects when it comes to providing public goods such as climate and environmental protection. However, additional incentives are needed to encourage farmers to adopt more agri-environmental measures (Schumacher, 2019).

In promoting the adoption of sustainable agri-environmental practices, an important task for agricultural policy in Germany and beyond is to understand which practices farmers can adopt in order to improve the environmental quality of agroecosystems effectively. Currently, agri-environmental policy is often a result of political compromises rather than evidence-based investigations (Brown et al. 2021; Pe’er et al. 2017). Identifying sustainable agricultural practices involves considering numerous social, ecological and environmental criteria, and there is currently a lack of knowledge regarding the overall impacts of specific practices. Moreover, the evidence pointing to environmentally beneficial practices is scattered among numerous sources, with no systematic overview available to date. While the project Conservation Evidence summarizes the effects of conservation actions on biodiversity in a variety of domains (gardening, forestry, etc.) (Conservation Evidence—Site, 2020), it does not address agri-environmental measures and it does not consider the domains of water, soil and climate change in addition to biodiversity. The present article offers a review to fill this research gap by identifying sustainable agri-environmental practices investigated in the academic literature and by analyzing their effects in relation to four major environmental domains (water quality, soil health, biodiversity and climate change) (Campbell et al. 2017; German et al. 2017). These domains were chosen for two reasons: (1) the influence of agricultural production on them is especially prominent, and (2) they encompass the most important aspects of environmental sustainability.

Wherever the relevant information is available, the review contrasts the impacts of the practices with information about their economic costs (including opportunity costs). By evaluating each practice, the present study synthesizes the state of knowledge about agri-environmental practices and their impacts on the environment. It additionally explores the synergies and trade-offs of different practices in terms of a set of sustainability indicators (Cord et al. 2017). This may assist policy makers in making better informed decisions regarding which particular practices should be supported.

Methodology

Review method

In this “review of reviews”, only meta-analyses and literature reviews were considered given the vast number of individual and often very context-specific studies linking agri-environmental practices to selected sustainability indicators. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) protocol was adapted to the particularities of this study (Moher et al. 2009).

The literature search was restricted to meta-analyses and reviews published in the last 10 years (since 2011) as well as to publications written in English or German. The review focuses on agri-environmental practices relevant to German farmers, including studies from other countries with comparable natural and structural conditions (Europe, USA, Canada, New Zealand and Australia) that covered management practices applicable to German agriculture. Accordingly, practices relevant to olive cultivation in Spain were excluded, while practices targeting wheat cultivation in the USA were included. Global studies were included if they reported results relevant to German agriculture that were structured according to country, continent or climate region. The four-level search string (Table 1) was applied to the databases Scopus and Web of Science. The term “animal welfare” was excluded on the basis of previous experience with similar search exercises, in order to ensure that only practices relevant to climate change, biodiversity, soil and water would appear.

The search strings were applied to the two databases in March 2020 and yielded 975 results (supplementary material 5: PRISMA flow diagram). Correction for duplicates reduced the number of publications to 710. Of these 710 publications, 401 were excluded when a screening of their titles and abstracts revealed that the study context was (i) not relevant to German agriculture or (ii) related to activities after harvest (i.e. food/feed storage, transport or processing), (iii) did not focus on agricultural production, sustainable agriculture or at least one of the four environmental domains of the study, or (iv) did not include any agri-environmental practices.

The remaining 309 publications were subjected to full-text analysis. The following information was extracted: the agri-environmental practices and the environmental domains dealt with in the study (i.e. biodiversity, climate change, water and/or soil), the specific area of focus (e.g. insects, carbon dioxide emissions) if applicable, the type of farming to which the practice relates (e.g. livestock, arable farming) as well as other characteristics of the publication, including the metadata (i.e. author, author institution, country, year, title, journal, citation, DOI) and method (e.g. meta-analysis, literature review). A full list of extracted categories can be found in the supplementary material (supplementary material 3: Publication information and exclusion criteria).

Another 211 publications were excluded during the full-text analysis since they either failed to meet the criteria defined above or an additional set of inclusion criteria that could only be determined by reading the texts in full. Specifically, only studies investigating an agri-environmental practice that met the following inclusion criteria were considered relevant: (1) farmers can potentially implement the practices (i.e. the agent of change is the farmer); (2) the practice and its implementation are characterized in detail; and (3) the aim of the practice is to improve environmental conditions. The final database includes 98 academic publications (see supplementary material 7: Meta-analyses and reviews).

Analysis of practices

In order to categorize all the agri-environmental practices identified, eight categories were developed inductively during the review process: (1) Fertilizer strategies, (2) Cultivation, (3) Planting: vegetation, landscape elements & other, (4) Grazing strategies, (5) Feeding strategies, (6) Stable management, (7) Other, (8) Combined practices & bundles.

The category “Fertilizer strategies” includes practices regarding the timing, manner, type as well as tools of fertilization. “Cultivation” includes practices that are applied directly to arable land such as choice of crop type, irrigation, use of pesticides or herbicides, and tillage excluding fertilizer practices. “Planting: vegetation, landscape elements & other” includes practices that refer to different plantings such as trees, hedges, buffers or flowers as well as practices that include plantings such as silvopasture or agri-silviculture. Practices included in the category “Grazing strategies” refer to different grazing patterns, types or timing of grazing. “Feeding strategies” include practices relating to livestock feed such as the use of dietary additives, bacteria or forage plants. The practices included in the category “Stable management” refer to wind speed, air scrubbers and the floor management of a stable. Practices included in the category “Other” include those that did not fit into any of the other categories. Examples include denitrification barriers, crop livestock integration or (woodchip) bioreactors (i.e. trenches in the subsurface filled with carbon sources (here: woodchips) through which water flows before leaving the drain to enter a surface water body). The category “Combined practices & bundles” includes practices comprising at least two agri-environmental practices, for example implementing no-tillage and cover crops (i.e. crops that are grown to protect soil health rather than to be harvested) at the same time.

Moreover, the effect of each practice on the four major environmental domains climate change, soil, water and biodiversity was analyzed in terms of environmental indicators used in the studies reviewed (e.g. CO2 emissions for “climate change” or soil porosity for “soil”). An economic dimension was included if the relevant indicators were present (e.g. cash crop yield). Sixteen distinct indicators were found for “climate change”, 63 for “soil”, 39 for “water”, two for “biodiversity” and 12 for the “economic dimension” (supplementary material 2: Definitions of environmental indicators; Table 2). Since information on the economic impacts of the practices was relatively scarce, tables including the economic dimension are only included in the supplementary material (supplementary material 4: Agri-environmental practices impact tables) Tables 3 and 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9.

The impacts of the environmental and economic indicators were summarized as follows: if at least two-thirds of the indicators for a given domain have a given direction of impact (positive/neutral/negative effect), the overall impact is interpreted accordingly. If at least 90% of the indicators within an environmental domain are fully (90% or more) positive/negative and the practice was investigated in at least two publications, the effect is interpreted as being consistently positive/consistently negative and colour-coded accordingly. If the indicators are divided equally into positive and negative indicators, they are interpreted as unclear; the same goes for impacts that include negative, neutral and positive indicator directions if none of them has a share of more than two-thirds. In other combinations (e.g. 50% positive and 50% neutral), the inferior effect is assumed to be “representative” (here: neutral). The impacts of the indicators are based on their consistency across publications. Due to the diversity of measures and units used within and across indicators, the study cannot make any assumptions or statements about the magnitude of the effects synthesized in it. Further details about the indicators and their impacts can be found in the supplementary material (supplementary material 1: Agri-environmental practices and their impact on environmental domains).

Results

Descriptive statistics

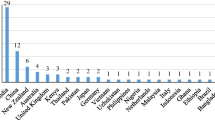

Among the 98 publications included in this review, a modest temporal trend is discernible: the number of publications increases slightly from 2014 onwards (Fig. 1). This might be explained by changes in the standards for literature reviews and meta-analyses over the years, as older reviews often lack a specific methodology and are generally less thorough (Snyder, 2019) and therefore did not meet the criteria for inclusion in this study. Another explanation for the trend could be the general rise in the number of publications over the years.

A total of 327 investigations (here: impact of a practice on an environmental indicators) of 144 distinct agri-environmental practices were identified. The most commonly investigated practices were those in the “Cultivation” category (108 times = 33.0%) and included primarily tillage practices and cover crops. Practices in the category “Fertilizer strategies” were investigated 88 times (26.9%) and practices in the category “Planting: vegetation, landscape elements & other” 64 times (19.6%). Less frequently investigated were practices in the categories “Grazing strategies” (5.2%), “Combined practices & bundles” (4.9%), “Other” (4.0%), “Stable management” (3.4%) and “Feeding strategies” (3.1%).

Table 2 presents the numbers of publications, environmental indicators and practices included within each category. It also shows how many practices were investigated with respect to each environmental domain, the number of environmental indicators per domain and the number of publications addressing each domain. The category “Planting: vegetation, landscape elements & other”, for example consists of 26 agri-environmental practices and includes 48 environmental indicators. Thirty-one publications investigated practices in this category. Also, eight publications analyzed eight environmental indicators for 14 “Planting” practices with respect to the environmental domain “climate change”. The number of distinct publications included in a category does not necessarily match the number of practices, since many publications investigated more than one practice in more than one category. The table in the supplementary material 6 highlights research gaps for each environmental domain and category. With regard to “Fertilizer strategies”, data for “biodiversity” are only available for 19 out of 42 practices, whereas “climate change” is quite well covered (36 out of 42). With regard to “Cultivation” practices, data are generally distributed evenly among the environmental domains. There is low coverage of “water” and “climate change” for the “Planting” category. Supplementary material 6 additionally shows a clear lack of research on the impacts of “Combined practices” on “climate change”. The effect of “Grazing strategies” on “climate change” and “soil” is not covered at all. The effects on “biodiversity” are not well researched and it has the lowest coverage in relation to “Fertilizer strategies”, “Cultivation” (together with “climate change”), “Stable management” and “Feeding strategies” (together with “soil” and “water”) and “Other”. Research investigating impacts on “biodiversity” concentrate on “Planting” and “Grazing strategies”, even though other practices in other categories may strongly affect “biodiversity”. However, not all practices can be investigated in relation to all four environmental domains, as some practices are too specific.

Synthesis of environmental impacts by practice category

The tables in this section present practices included in the eight distinct categories and their impact on the four environmental domains. The categories are arranged according to three broad topics: arable land (“Fertiilzer strategies”, “Cultivation” and “Planting: vegetation, landscape elements & other”), grassland (“Grazing strategies”) and livestock (“Feeding strategies” and “Stable management”). The categories “Other” as well as “Combined practices & bundles” are presented further below.

Fertilizer strategies

Table 2 shows 42 practices included in the category “Fertilizer strategies” and their impact on each environmental domain. Nineteen practices were analyzed with respect to each of the four environmental domains, two practices with respect to three, one with respect to two and twenty with respect to just one.

Many practices in this category have positive impacts on all four environmental domains. In particular, “water” and “soil” have a high relative share of positive effects. However, in relation to several practices, there is a lack of data for some environmental domains. This is especially the case for “biodiversity” (data for only 19 practices), but also applies to “water” and “soil” (23 and 26 practices with data respectively).

Practices with a consistently positive environmental impact and good availability of data are controlled-release fertilizer (i.e. a granulated fertilizer that releases nutrients gradually into the soil), fertilizer with urease inhibitors and deep placement of fertilizer. Amendments (e.g. applying organic amendments or pyrise/zeolite) and practices addressing the storage of manure (e.g. manure covers) have continuously positive effects on environmental domains. Conversely, the application of ammonium bicarbonate has been found to have negative impacts on all four environmental domains. The impacts of urea on the four environmental domains appear to be unclear; using non-urea-based fertilizer or fertilizer with urease inhibitors has a positive impact on the four environmental domains considered. However, the impact of using urea ammonium nitrate or polymer-coated urea is neutral. The apparent positive effects of avoiding urea are interesting, because although the latest fertilizer ordinance in Germany (2017) allows the application of urea fertilizers if a urease inhibitor has been added, urease can also be used without urease inhibitors if it is incorporated immediately (i.e. not later than four hours after application).

While adjusting the fertilizer input to crop needs has a positive impact, changing the fertilizer rate and timing (e.g. delaying fertilizer application) has mixed effects on the environmental domains.

Cultivation

Table 3 presents 29 practices included in the category “Cultivation” and their impact on each environmental domain. Eight practices were analyzed with respect to each of the four environmental domains, three practices with respect to three, five with respect to two and thirteen with respect to only one.

The practices included in this category have positive effects on the environmental domains “climate change”, “soil”, “water” and consistently positive effects on “biodiversity”. There is no practice in this category that has solely negative effects on the four environmental domains considered, and only two practices have any negative effects at all (crop rotation/climate and intercropping with undersown cover/soil). For several practices, however, there is a lack of data on environmental impacts on some of the domains, especially “biodiversity” (no data for 15 out of 29 practices), “climate change” (15) and “water” (14).

Interestingly, precision agriculture is analyzed by only one publication, despite the fact that it is an increasingly popular topic in policy and practice and is assumed to have numerous benefits for the environment and farmers alike due to the targeted use of inputs (Finger et al. 2019).

Using organic or natural inputs has been found to have only beneficial effects on the environmental domains (i.e. using additional organic matter and either no herbicides or pesticides or only natural ones).

Varying crops has contradictory results: intercropping (i.e. growing two or more crops simultaneously on the same land), crop establishment (transplanting rather than sowing whenever possible and choosing an adequate date and mode of sowing and transplanting, e.g. sowing depth, inter-row distance, accurate steering) and crop diversification (i.e. growing more than one crop on a given site) have positive effects on the environmental domains. However, the impacts of crop rotation (i.e. growing a series of different crops on the same site in different growing seasons) on the four environmental domains considered are rather unclear; indeed, for “climate change”, the impact is negative.

Controlled traffic farming (i.e. reducing soil compaction caused by agricultural machinery) is one aspect of no-tillage and reduced tillage practices, and has only positive effects on the environmental domains. Tillage practices per se, however, have several unclear effects on the environment.

Cover crops have mostly positive effects on the four environmental domains considered, yet the impact on “climate change” is unclear. This may be due to the many types of cover crops and other influencing domains such as soil type, climatic region or the cash crop (for more specific interconnections, see supplementary material 1: Agri-environmental practices and their impact on environmental domains).

Irrigation stands out because it is found to be consistently positive for all four environmental domains. This is due to the baselines of the reviews and meta-analyses (here, for example drip irrigated systems vs. sprinkler systems, localized irrigation—e.g. sub-irrigation—vs. standard irrigation, improved irrigation and technology vs. standard irrigation). Thus, practicing irrigation in general might not be beneficial for the four environmental domains considered, but if a farmer already uses irrigation practices, then specific variants of these practices may serve to mitigate the negative effects. Further details about the baselines of each practice can be found in the supplementary material (supplementary material 1: Agri-environmental practices and their impact on environmental domains).

Planting: vegetation, landscape elements & other

Table 4 presents 26 practices included in the category “Planting: vegetation, landscape elements & other” and their impact on each of the four environmental domains considered here. Four practices within the category were analyzed with respect to each environmental domain, eight practices with respect to three, eleven with respect to two and four with respect to only one. Regarding this category, the environmental domain “water” has the largest data deficit (15 of 26 practices without data), but also “climate change” data are missing for around half the practices in this category (12 of 26).

Overall, the practices within this category have predominantly positive effects, with only few ambiguous and negative effects on the environmental domains considered. Particularly, the impacts on “water”, “soil” and biodiversity” are consistently positive. Practices with data availability for each domain and positive environmental impact are other plantings (here: wide-space belts and gully wall plantings, for example), grassed waterways, terraces, contour farming, filter strips and/or riparian buffers and strips as well as borders of non-crop vegetation around agricultural land. The least promising practices are short-rotation woody cropping (i.e. woody tree species with extremely high rates of growth) in silvicultural systems and skylark plots (i.e. small undrilled patches within cereal fields) although there is too little literature available to make any general assumptions.

Practices that include flowers or hedgerows have been found to have only positive impacts on the environmental domains, while the results of practices including trees are more ambiguous. Growing crops and trees on the same piece of land (i.e. agri-silvicultural systems), integrating trees, forage and grazing (i.e. silvopasture) as well as planting trees and shrubs on field margins have positive effects on the environmental domains of “soil”, “water” and “biodiversity” but mixed effects on “climate change”. The reason for mixed effects on climate change can be found in the baseline used for the analysis and other domains (e.g. time elapsed since the practice was implemented, region). Details for each domain can be found in the supplementary material (supplementary material 1: Agri-environmental practices and their impact on environmental domains).

Grazing strategies

Table 5 presents seven practices included in the category “Grazing stategies” and their impact on each environmental domain. No practice was analyzed with respect to all four environmental domains, three practices were analyzed with respect to three, one with respect to two and three with respect to only one domain. Interestingly, no publication investigated the impact of grazing strategies on “climate change”. In some instances, there is also a lack of data for other environmental domains.

Grazing strategies have a consistently positive effect on “biodiversity”, while their effects on “soil” and “water” are ambiguous.

Continuous moderate grazing has the most reliable positive environmental impact. The other practices are either less promising or else there is only limited data available for different environmental domains. In particular, livestock grazing has rather disadvantageous effects on the environmental domains.

The practice of livestock grazing in general seems to have negative impacts on the four environmental domains considered. This applies to grazing in salt marshes, croplands and wetlands. Moreover, grazing seems to have negative impacts if the baseline is “ungrazed areas” or “no grazing”. However, if a farmer already practices grazing, introducing grazing strategies seems to reduce the negative impacts to some extent and is therefore preferable to not using grazing strategies.

Feeding strategies

Table 6 presents six practices included in the category “Feeding strategies” and their impact on each environmental domain. Five practices within the category were analyzed with respect to each of the four environmental domains and one practice with respect to only one. Data are readily available for this category; there is a lack of data only regarding the cultivation of more nutritious forage plants.

Overall, the practices within this category have positive effects on the four environmental domains. For the domains “soil”, “water” and “biodiversity”, the overall effect of the practices is consistently positive. The practice of introducing dietary additives has unclear impacts on “climate change” as measured by the environmental indicators. This might result from the large number of dietary additives and livestock combinations (Lewis et al. 2015). Using dietary acidifier, dietary bacteria and yucca extract or reducing the crude protein content all have rather beneficial impacts on all four environmental domains.

Stable management

Table 7 presents eleven practices included in the category “Stable management” and their impact on each environmental domain. Five practices within the category were analyzed with respect to each of the four environmental domains and six practices with respect to only one. No data exist for “soil”, “water” and “biodiversity”.

Overall, the practices within this category have positive effects on the environmental domains while the environmental indicators were found to be in synergy with each other. However, only three publications were included in the category, which again makes it difficult to provide general statements about the effects of “Stable management” on the four environmental domains considered.

Interestingly, reducing ventilation rates inside the barn has positive effects on “climate change”, whereas changing the wind speed inside the barn has no significant effect on “climate change”. This could be due to the fact that air velocities are highly variable inside barns (Sanchis et al. 2019).

Other

Table 8 presents ten practices included in the category “Other” and their impact on each of the four environmental domains. Practices within this category did not fit into any of the other categories and come from various thematic areas. Three practices were analyzed with respect to each of the four environmental domains, one practice with respect to three, two with respect to two and four with respect to only one. There is a lack of data particularly for “biodiversity”. For most practices in this category, the environmental effects were found to be positive.

Practices that have positive effects on all the environmental domains are crop livestock integration and denitrification barriers. This is in line with the previous findings, where we saw that a similar trend can be observed for the integration of crops and trees (agri-silvicultural systems) and the integration of trees/forage and grazing (silvopasture).

Just as the practice of livestock grazing seems to have negative impacts on the environment, the practice of promoting livestock (i.e. beef production) also seems to have negative impacts on the environmental indicators. However, if a farmer already practices cattle farming, then introducing different agri-environmental practices may impact the environment positively (Pogue et al. 2018). Other practices within the category (e.g. vermicomposting, a process by which various species of worms are used to convert organic material into vermicompost, or establishing and maintaining wetlands) are also advantageous for the environment. However, data are lacking for several domains.

Combined practices & bundles

Table 9 presents twelve practices included in the category “Combined practices & bundles” and their impact on each environmental domain. Within this category, no practice was analyzed with respect to each of the four environmental domains, three practices were analyzed with respect to three, one with respect to two and nine with respect to only one. Data are lacking in particular for the environmental domains of “climate change” and “biodiversity”.

This category is rather interesting, since practices that are adopted in bundles may have other impacts on the environment than each of them when adopted alone. The bundles “conservation agriculture” and “organic agriculture” were included only if the publication specifically stated which practices were tested and included within the study (supplementary material 1: Agri-environmental practices and their impact on environmental domains).

Adoption of one practice often triggers complementary adoption of other practices (e.g. a switch to no-till usually requires application of herbicides). As single practices, introducing cover crops was found to have neutral effects on “climate change”, positive effects on “soil” and “water” and consistently positive effects on “biodiversity” (see Table 33 above). Using no-tillage appears to have positive effects on “climate change”, unclear effects on “soil” and “water” and positive effects on “biodiversity” (Table 33). This review revealed that combining cover crops and no-tillage improves the environmental performance of the latter especially.

Almost every practice within this category has positive effects on the four environmental domains considered, with the sole exception of fallow with no-tillage and dead mulches, which has been found to have non-significant effects on “biodiversity”. This arguably indicates that bundles may compensate each other’s shortcomings. Especially the domains “water” and “soil” have been found to benefit from the practices within this category.

Discussion

This study synthesized the empirical results regarding the effects of 144 agri-environmental practices on four environmental domains—biodiversity, water quality, soil health and climate change—using 132 environmental indicators. Some practices were prevalent (e.g. cover crops or tillage practices) and others were unexpectedly underrepresented (e.g. precision agriculture). The latter does not imply that empirical studies investigating the effects of precision agriculture on the environment do not exist (e.g. Jensen et al. 2012) but rather that there are very few literature reviews or meta-analysis of the topic.

Summary of findings

In all the categories of agricultural practices, the effects of the practices were consistent across each of the four environmental domains considered, and few trade-offs are apparent. However, some practices are clearly beneficial for one environmental domain and problematic for another: the environmental domain of “climate”, for example was found to occur most often in trade-offs. A trade-off occurs if a practice has unclear, negative or consistently negative effects on one environmental domain and positive effects on others.

Looking at practices applied on arable land, modes of fertilizer application are particularly important in terms of environmental impacts. Similarly, amendments and practices addressing the storage of manure (with clear links to livestock production) have consistently positive effects on environmental impact areas. Practices using organic and natural inputs have been found to be beneficial for the four environmental domains considered. Adaptation of these practices applied on arable land can therefore be seen as an opportunity for sustainable agriculture in Germany. The overall picture is more unclear in the context of grasslands (i.e. “Grazing strategies”), as compared to arable land. In particular, the effects of relevant practices on “soil” and “water” are unclear and little data is available for “climate change”.

This review revealed that in many cases (e.g. irrigation, field margin plants such as trees and shrubs) there is an important difference between the implementation and the design of a practice. This means that the way a practice is implemented depends largely on the baseline, that is on the (environmental) conditions in which the practice is applied. If, however, a practice is already being applied, there are several possible modes of implementation that can compensate for any negative impacts. The following example illustrates this. Generally, livestock grazing has negative impacts on the four environmental domains considered. However, if a farmer already practices grazing, introducing specific grazing strategies can at least partly offset the negative impacts. This demonstrates the importance of explicitly considering the baseline used to evaluate the environmental impacts of agricultural practices. However, other domains such as animal welfare should also be included in the decision-making process. Importantly, these insights should be considered in a context-specific way to inform farm management and agri-environmental policy. The analysis of practice bundles, which are even more context-sensitive than individual practices, shows that a combination of practices can sometimes offset the negative impacts of individual practices. Practice bundles are a promising approach; however, more research is needed, especially regarding the domain of climate change.

Limitations

The findings of this study are subject to certain limitations. First, the impacts of practices on environmental domains were summarized qualitatively, based on the number and direction of the environmental indicators across studies, without considering issues of comparability between indicators or, more significantly, the magnitude of the effects. Summarizing the effects in such a qualitative way may result in counting the same environmental indicator twice if it appears in different studies for the same practice. For transparency on this point, all the indicators that form the basis of the summary impacts can be viewed in the supplementary material (supplementary material 1: Agri-environmental practices and their impact on environmental domains). Second, the methodologies of the studies reviewed here were not evaluated in detail, so that the quality of the studies included is likely to vary. The minimum standard requirement used here was to include only those publications with a semi-systematic method. Future research could investigate the magnitude of the effects of those practices identified as beneficial in this study. Third, the approach used in this review of reviews required several subjective judgements, particularly when it came to defining categories of practices and deciding on the environmental domains to be included. This was necessary to increase the interpretability of the results, but it necessarily involves ambiguities. To minimize any potential bias, we provide more detailed accompanying information wherever possible (including the supplementary material).

Policy implications and further research

This review has uncovered substantial knowledge gaps (supplementary material 6: Descriptive statistics of for categories of practices). For instance, no syntheses are available on the climate effects of grazing or combined practices. In the category “Planting: vegetation, landscape elements & other”, “climate change” data are lacking for around half the practices. This is interesting, as the positive relationship between landscape elements, vegetation and climate resilience is firmly embedded in the CAP’s support for ecological focus areas (European Comission 2017). Similarly, the scarcity of data for the impacts of fertilizer strategies on “water” is highly policy-relevant, because several CAP cross-compliance measures refer to the impacts of fertilization on water quality (e.g. good agricultural and environmental conditions) (European Comission 2020). While research may exist on these questions, there is a need to synthesize the relevant findings in order to provide a sound basis for policy making. At least equally important is the fact that only very few publications integrated the economic dimension into the analysis. Yet consideration of not only the environmental benefits of practices but also their associated (opportunity) costs and, ultimately, their economic feasibility is crucial to developing robust agri-environmental policy. Further research should examine the costs of agricultural practices, since knowledge of opportunity costs is essential to selecting suitable agri-environmental management practices.

The suitability and environmental impacts of agri-environmental practices are highly context dependent; many different farming contexts exist even in Germany alone (Seufert and Ramankutty, 2017). In a meta-analysis of environmental domains driving the effectiveness of agri-environmental pollinator practices, Scheper et al. (2013) found that the impact of practices on the environment varies with the landscape context in which they are applied. Similarly, Graham et al. (2018) and Jian et al. (2020), both of which were included in this review, emphasize that the impact of practices varies with the context in which they are applied, i.e. how, when and where they are adopted (e.g. which hedgerow is beneficial for which insect, or which cover crop is advantageous for the environment may depend on the cash crop that follows, soil type or on the climatic region). The publications which included the impact of practices in different contexts relevant to German farmers can be viewed in the supplementary material (supplementary material 1: Agri-environmental practices and their impact on environmental domains); these impacts can be very heterogeneous and may differ from the synthesized effects of all contexts shown in the present study. This has important implications for policy, as one-size-fits-all approaches are not the best choice; policies should rather be flexible, scalable and adaptable to local conditions. Thus, knowledge of local situations is crucial, and approaches such as result-based schemes (i.e. offering the farmer a payment conditional on achieving a quantifiable environmental objective while leaving the choice of action to achieve the objective up to the farmer) should be given preference over the more widespread action-based schemes (i.e. offering the farmer a uniform payment for adopting specific agri-environmental practices) (Bartkowski et al. 2021). This view is supported by Schlaich et al. (2015) as well as Walker et al. (2018), who find that if agri-environmental practices are geographically and ecologically targeted, agri-environmental practices deliver expected environmental outcomes.

Based on the results of this review, the application of individual practices relevant to German farmers (e.g. planting strips and borders of non-crop vegetation around farmland) can be recommended and may serve as a basis for policy interventions with clear environmental objectives. However, as the impact of various practices on the environment depends crucially on the context of application, most emphasis should be placed on practices that have been found to be consistently positive across several environmental domains. This study reveals that bundles of practices relevant to German farmers have consistently positive impacts on the four environmental domains considered, since the adoption of a practice often implies the adoption of other, complementary practices. These results support the approach of providing incentives for more holistic changes in agricultural management, shifting the focus from applying agricultural practices in a “pick-and-mix” manner to considering the farming system in question as a whole (cf. Leventon et al. 2019). However, further research needs to address the direct comparison between bundles and single practices, as the bundles considered in this review consist of coherent practices (i.e. the way different practices complement one another was considered in their selection as a bundle). Furthermore, more research is needed into how policy design and different governance approaches can facilitate the context-specific adoption and implementation of sustainable practices.

Rockström et al. (2017) describe the vision of a paradigm shift in agriculture that would transform it from its current role as a major contributor to global environmental change to that of being a key driver of the global transition to a sustainable world. Agri-environmental practices are a key component of this transition. In their analysis of the importance of agricultural production in efforts to curtail anthropogenic climate change, Lynch et al. (2021) emphasize that climate change mitigation in agriculture is a very broad topic that needs to consider many factors, including economic feasibility.

To conclude, this review examines a wide range of agri-environmental practices as well as practice bundles incorporated into eight distinct categories (i.e. “Fertilizer strategies”, “Cultivation”, “Planting: vegetation, landscape elements & other”, “Grazing strategies”, “Feeding strategies”, “Stable management”, “Other” and “Combined practices and bundles”) and their impacts on key environmental domains. It thus provides a degree of orientation as to which practices can be used in a transition toward more sustainable agriculture in Germany. In addition, the present review contributes toward research on anthropogenic climate change by not only investigating the feasibility of agri-environmental practices to mitigate climate change but also illustrating the synergies and trade-offs with other environmental domains.

Supplementary information.

Notes

The term “agri-environmental practices” is used in this paper to describe agricultural practices with a high impact on the environment (i.e. the focus of the review); these should not be confused with “agri-environmental measures” (e.g. agri-environment and climate measures, i.e. payment schemes within the EU CAP).

References

Abalos D, Jeffery S, Drury CF, Wagner-Riddle C (2016) Improving fertilizer management in the U.S. and Canada for N2O mitigation: understanding potential positive and negative side-effects on corn yields. Agr Ecosyst Environ 221:214–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2016.01.044

Aguilera E, Lassaletta L, Gattinger A, Gimeno BS (2013) Managing soil carbon for climate change mitigation and adaptation in Mediterranean cropping systems: a meta-analysis. Agr Ecosyst Environ 168:25–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2013.02.003

Aronsson H, Hansen EM, Thomsen IK, Liu J, Øgaard AF et al (2016) The ability of cover crops to reduce nitrogen and phosphorus losses from arable land in southern Scandinavia and Finland. J Soil Water Conserv 71(1):41–55. https://doi.org/10.2489/jswc.71.1.41

Bai Z, Caspari T, Gonzalez MR, Batjes NH, Mäder P et al (2018) Effects of agricultural management practices on soil quality: a review of long-term experiments for Europe and China. Agr Ecosyst Environ 265:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2018.05.028

Barral MP, Rey Benayas JM, Meli P, Maceira NO (2015) Quantifying the impacts of ecological restoration on biodiversity and ecosystem services in agroecosystems: a global meta-analysis. Agr Ecosyst Environ 202:223–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2015.01.009

Barthod J, Rumpel C, Dignac MF (2018) Composting with additives to improve organic amendments. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 38(2). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-018-0491-9

Bartkowski B, Droste N, Ließ M, Sidemo-Holm W, Weller U et al (2021) Payments by modelled results: a novel design for agri-environmental schemes. Land Use Policy 102(105230). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105230

Basche AD, DeLonge MS (2019) Comparing infiltration rates in soils managed with conventional and alternative farming methods: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 14(9):1–22. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215702

Bednarek A, Szklarek S, Zalewski M (2014) Nitrogen pollution removal from areas of intensive farming-comparison of various denitrification biotechnologies. Ecohydrol Hydrobiol 14(2):132–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecohyd.2014.01.005

Beillouin D, Ben-Ari T, Makowski D (2019) Evidence map of crop diversification strategies at the global scale. Environ Res Lett 14. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab4449

Bell LW, Moore AD, Kirkegaard JA (2014) Evolution in crop-livestock integration systems that improve farm productivity and environmental performance in Australia. Eur J Agron 57:10–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2013.04.007

Bentrup G, Hopwood J, Adamson NL, Vaughan M (2019) Temperate agroforestry systems and insect pollinators: A review. Forests 10(11):14–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10110981

Borchard N, Schirrmann M, Cayuela ML, Kammann C, Wrage-Mönnig N et al (2019) Biochar, soil and land-use interactions that reduce nitrate leaching and N2O emissions: a meta-analysis. Sci Total Environ 651:2354–2364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.10.060

Borrelli P, Robinson DA, Panagos P, Lugato E, Yang JE et al (2020) Land use and climate change impacts on global soil erosion by water (2015–2070). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117(36):21994–22001. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2001403117

Bowles TM, Jackson LE, Loeher M, Cavagnaro TR (2017) Ecological intensification and arbuscular mycorrhizas: a meta-analysis of tillage and cover crop effects. J Appl Ecol 54(6):1785–1793. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12815

BMEL (2021) Ackerbaustrategie 2035 - Perspektiven für einen produktiven und vielfältigen Pflanzenbau. https://www.bmel.de/DE/themen/landwirtschaft/pflanzenbau/ackerbau/ackerbaustrategie.html. Accessed 06.02.22

Brown C, Kovács E, Herzon I, Villamayor-Tomas S, Albizua A et al (2021) Simplistic understandings of farmer motivations could undermine the environmental potential of the common agricultural policy. Land Use Policy 101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105136

Campbell BM, Beare DJ, Bennett EM, Hall-Spencer JM, Ingram JSI et al (2017) Agriculture production as a major driver of the earth system exceeding planetary boundaries. Ecol Soc 22(4):8. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09595-220408

Christen B, Dalgaard T (2013) Buffers for biomass production in temperate European agriculture: a review and synthesis on function, ecosystem services and implementation. Biomass Bioenerg 55:53–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2012.09.053

Christianson L, Knoot T, Larsen D, Tyndall J, Helmers M (2014) Adoption potential of nitrate mitigation practices: an ecosystem services approach. Int J Agric Sustain 12(4):407–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2013.835604

Clark MA, Domingo NGG, Colgan K, Thakrar SK, Tilman D et al (2020) Global food system emissions could preclude achieving the 1.5° and 2°C climate change targets. Science 370(6517):705–708. https://doi.org/10.5880/pik.2019.001

European Comission (2017) Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the implementation of the ecological focus area obligation under the green direct payment scheme. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52017DC0152. Accessed 05 June 2020

European Comission (2020) Safe water - the common agricultural policy helps to protect the essential role that water plays for food, farming, and the environment. https://ec.europa.eu/info/food-farming-fisheries/sustainability/environmental-sustainability/natural-resources/water_en#capactions. Accessed 10 Nov 2020

Cooper J, Baranski M, Stewart G, Nobel-de Lange M, Bàrberi P et al (2016) Shallow non-inversion tillage in organic farming maintains crop yields and increases soil C stocks: a meta-analysis. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 36(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-016-0354-1

Cord AF, Bartkowski B, Beckmann M, Dittrich A, Hermans-Neumann K, Kaim A, Lienhoop N, Locher-Krause K, Priess J, Schröter-Schlaack C, Schwarz N, Seppelt R, Strauch M, Václavík T, Volk M (2017) Towards systematic analyses of ecosystem service trade-offs and synergies: main concepts, methods and the road ahead. Ecosyst Serv 28:264–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.07.012

Cumplido-Marin L, Graves AR, Burgess PJ, Morhart C, Paris P et al (2020) Two novel energy crops: Sida hermaphrodita (L.) rusby and silphium perfoliatum l.-state of knowledge. Agronomy 10(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10070928

Daryanto S, Wang L, Jacinthe PA (2017) Meta-analysis of phosphorus loss from no-till soils. J Environ Qual 46(5):1028–1037. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2017.03.0121

Davidson KE, Fowler MS, Skov MW, Doerr SH, Beaumont N et al (2017) Livestock grazing alters multiple ecosystem properties and services in salt marshes: a meta-analysis. J Appl Ecol 54:1395–1405. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12892

Delonge M, Basche A (2018) Managing grazing lands to improve soils and promote climate change adaptation and mitigation: a global synthesis. Renewable Agric Food Syst 33(3):267–278. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742170517000588

Doody DG, Bailey JS, Watson CJ (2013) Evaluating the evidence-base for the Nitrate Directive regulations controlling the storage of manure in field heaps. Environ Sci Policy 29:137–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2013.01.009

Dörschner T, Musshoff O (2015) How do incentive-based environmental policies affect environment protection initiatives of farmers? An experimental economic analysis using the example of species richness. Ecol Econ 114:90–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.03.013

Elias D, Wang L, Jacinthe PA (2018) A meta-analysis of pesticide loss in runoff under conventional tillage and no-till management. Environ Monit Assess 190(2). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-017-6441-1

England J, R O’Grady AP, Fleming A, Marais Z, Mendham D (2020) Trees on farms to support natural capital: an evidence-based review for grazed dairy systems. Science of the Total Environment 704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135345

Espeland EK, Kettenring KM (2018) Strategic plant choices can alleviate climate change impacts: a review. J Environ Manage 222:316–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.05.042

Conservation Evidence - Site. (2020). https://www.conservationevidence.com/

Fan Y, Wang C, Nan Z (2018) Determining water use efficiency of wheat and cotton: a meta-regression analysis. Agric Water Manag 199:48–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2017.12.006

Feliciano D, Ledo A, Hillier J, Nayak DR (2018) Which agroforestry options give the greatest soil and above ground carbon benefits in different world regions? Agr Ecosyst Environ 254:117–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2017.11.032

Ferrarini A, Serra P, Almagro M, Trevisan M, Amaducci S (2017) Multiple ecosystem services provision and biomass logistics management in bioenergy buffers: a state-of-the-art review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 73:277–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.01.052

Finger R, Swinton SM, Benni NE, Achim W (2019) Precision farming at the nexus of agricultural production and the environment. Annual Review of Resource Economics 11:313–335. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-resource-100518-093929

Fowler HJ, Ali H, Allan RP, Ban N, Barbero R et al (2021) UK climate projections: convection-permitting model projections: Science report. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 379(2195). https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2019.0542

Garbach K, Milder JC, DeClerck FAJ, Montenegro de Wit M, Driscoll L, Gemmill-Herren B (2017) Examining multi-functionality for crop yield and ecosystem services in five systems of agroecological intensification. Int J Agric Sustain 15(1):11–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2016.1174810

Garratt MPD, Wright DJ, Leather SR (2011) The effects of farming system and fertilisers on pests and natural enemies: a synthesis of current research. Agr Ecosyst Environ 141(3–4):261–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2011.03.014

German RN, Thompson CE, Benton TG (2017) Relationships among multiple aspects of agriculture’s environmental impact and productivity: a meta-analysis to guide sustainable agriculture. Biol Rev 92(2):716–738. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12251

González-Sánchez EJ, Ordóñez-Fernández R, Carbonell-Bojollo R, Veroz-González O, Gil-Ribes JA (2012) Meta-analysis on atmospheric carbon capture in Spain through the use of conservation agriculture. Soil and Tillage Research 122:52–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2012.03.001

Graham L, Gaulton R, Gerard F, Staley JT (2018) The influence of hedgerow structural condition on wildlife habitat provision in farmed landscapes. Biol Cons 220:122–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2018.02.017

Grosse M, Heß J (2018) Sommerzwischenfrüchte für verbessertes Stickstoff- und Beikrautmanagement in ökologischen Anbausystemen mit reduzierter Bodenbearbeitung in den gemäßigten Breiten. J Kult 70(6):173–183

Haddaway NR, Hedlund K, Jackson LE, Kätterer T, Lugato E et al (2017). How does tillage intensity affect soil organic carbon? A systematic review. Environmental Evidence 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13750-017-0108-9

Han Z, Walter MT, Drinkwater LE (2017) N2O emissions from grain cropping systems: a meta-analysis of the impacts of fertilizer-based and ecologically-based nutrient management strategies. Nutr Cycl Agroecosyst 107(3):335–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10705-017-9836-z

Hansen S, Frøseth RB, Stenberg M, Stalenga J, Olesen JE et al (2019) Reviews and syntheses: review of causes and sources of N2O emissions and NO3 leaching from organic arable crop rotations. Biogeosciences 16(14):2795–2819. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-16-2795-2019

Hari V, Rakovec O, Markonis Y, Hanel M, Kumar R (2020) Increased future occurrences of the exceptional 2018–2019 Central European drought under global warming. Scientific Reports 10(12207). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-68872-9

Howell HJ, Mothes CC, Clements SL, Catania SV, Rothermel BB, Searcy CA (2019) Amphibian responses to livestock use of wetlands: new empirical data and a global review. Ecol Appl 29(8):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.1976

Jensen HG, Jacobsen LB, Pedersen SM, Tavella E (2012) Socioeconomic impact of widespread adoption of precision farming and controlled traffic systems in Denmark. Precision Agric 13(6):661–677. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-012-9276-3

Jian J, Lester BJ, Du X, Reiter MS, Stewart RD (2020) A calculator to quantify cover crop effects on soil health and productivity. Soil and Tillage Research 199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2020.104575

Jokubauskaite I, Karčauskienė D, Slepetiene A, Repsiene R, Amaleviciute K (2016) Effect of different fertilization modes on soil organic carbon sequestration in acid soils. Acta Agric Scand Sect B Soil Plant Sci 66(8):647–652. https://doi.org/10.1080/09064710.2016.1181200

Kallenbach C, Grandy AS (2011) Controls over soil microbial biomass responses to carbon amendments in agricultural systems: a meta-analysis. Agr Ecosyst Environ 144(1):241–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2011.08.020

Kämpf I, Hölzel N, Störrle M, Broll G, Kiehl K (2016) Potential of temperate agricultural soils for carbon sequestration: a meta-analysis of land-use effects. Sci Total Environ 566–567:428–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.05.067

Kroll SA, Oakland HC (2019) A review of studies documenting the effects of agricultural best management practices on physiochemical and biological measures of stream ecosystem integrity. Nat Areas J 39(1):78–89. https://doi.org/10.3375/043.039.0105

Lee MA, Davis AP, Chagunda MGG, Manning P (2017) Forage quality declines with rising temperatures, with implications for livestock production and methane emissions. Biogeosciences 14(6):1403–1417. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-14-1403-2017

Lee H, Lautenbach S, Nieto APG, Bondeau A, Cramer W, Geijzendorffer IR (2019) The impact of conservation farming practices on Mediterranean agro-ecosystem services provisioning—a meta-analysis. Reg Environ Change 19(8):2187–2202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-018-1447-y

Lefebvre M, Midler E, Bontems P (2020) Adoption of environment-friendly agricultural practices with background risk: experimental evidence. Environ Resource Econ 76(2–3):405–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-020-00431-2

Leventon J, Schaal T, Velten S, Loos J, Fischer J, Newig J (2019) Landscape-scale biodiversity governance: scenarios for reshaping spaces of governance. Environ Policy Gov 29(3):170–184. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1845

Lewis KA, Tzilivakis J, Green A, Warner DJ (2015) Potential of feed additives to improve the environmental impact of European livestock farming: a multi-issue analysis. Int J Agric Sustain 13(1):55–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2014.936189

Li J, Luo J, Shi Y, Houlbrooke D, Wang L et al (2015) Nitrogen gaseous emissions from farm effluent application to pastures and mitigation measures to reduce the emissions: a review. N Z J Agric Res 58(3):339–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/00288233.2015.1028651

Li Y, Chang SX, Tian L, Zhang Q (2018) Conservation agriculture practices increase soil microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen in agricultural soils: a global meta-analysis. Soil Biol Biochem 121:50–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.02.024

Lichtenberg EM, Kennedy CM, Kremen C, Batáry P, Berendse F et al (2017) A global synthesis of the effects of diversified farming systems on arthropod diversity within fields and across agricultural landscapes. Glob Change Biol 23(11):4946–4957. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13714

Lovarelli D, Bacenetti J, Guarino M (2020) A review on dairy cattle farming: Is precision livestock farming the compromise for an environmental, economic and social sustainable production? Journal of Cleaner Production 262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121409

Lynch J, Cain M, Frame D, Pierrehumbert R (2021) Agriculture’s contribution to climate change and role in mitigation is distinct from predominantly fossil CO2-emitting sectors. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 4:1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2020.518039

Martin-Guay MO, Paquette A, Dupras J, Rivest D (2018) The new green revolution: sustainable intensification of agriculture by intercropping. Sci Total Environ 615:767–772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.10.024

McDonald SE, Lawrence R, Kendall L, Rader R (2019) Ecological, biophysical and production effects of incorporating rest into grazing regimes: a global meta-analysis. J Appl Ecol 56(12):2723–2731. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13496

Mkenda PA, Ndakidemi PA, Mbega E, Stevenson PC, Arnold SEJ et al (2019) Multiple ecosystem services from field margin vegetation for ecological sustainability in agriculture: Scientific evidence and knowledge gaps. PeerJ 2019(11):1–33. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.8091

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine 6(7). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Moos JH, Schrader S, Paulsen HM (2017) Reduced tillage enhances earthworm abundance and biomass in organic farming: a meta-analysis. Landbauforschung 67(3–4):123–128. https://doi.org/10.3220/LBF1512114926000

Mouazen AM, Palmqvist M (2015) Development of a framework for the evaluation of the environmental benefits of controlled traffic farming. Sustainability (switzerland) 7(7):8684–8708. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7078684

Mphande W, Kettlewell PS, Grove IG, Farrell AD (2020) The potential of antitranspirants in drought management of arable crops: a review. Agricultural Water Management 236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2020.106143

Muirhead RW (2019) The effectiveness of streambank fencing to improve microbial water quality: a review. Agricultural Water Management 223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2019.105684

Nicholls CI, Altieri MA (2013) Plant biodiversity enhances bees and other insect pollinators in agroecosystems. A Review Agronomy for Sustainable Development 33(2):257–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-012-0092-y

Nistor E, Dobrei AG, Dobrei A, Camen D, Sala F et al (2018). N2O, CO2, Production, and C Sequestration in Vineyards: a Review. Water, Air, and Soil Pollution 229(9). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-018-3942-7

Nummer SA, Qian SS, Harmel RD (2018) A meta-analysis on the effect of agricultural conservation practices on nutrient loss. J Environ Qual 47(5):1172–1178. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2018.01.0036

Öllerer K, Varga A, Kirby K, Demeter L, Biró M et al (2019) Beyond the obvious impact of domestic livestock grazing on temperate forest vegetation – a global review. Biol Cons 237:209–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.07.007

Palomo-Campesino S, González JA, García-Llorente M (2018) Exploring the connections between agroecological practices and ecosystem services: a systematic literature review. Sustainability (Switzerland) 10(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124339

Pamminger T, Becker R, Himmelreich S, Schneider CW, Bergtold M (2019) The nectar report: quantitative review of nectar sugar concentrations offered by bee visited flowers in agricultural and non-agricultural landscapes. Peer J (2). https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.6329

Pan B, Lam SK, Mosier A, Luo Y, Chen D (2016) Ammonia volatilization from synthetic fertilizers and its mitigation strategies: a global synthesis. Agr Ecosyst Environ 232:283–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2016.08.019

Pannacci E, Lattanzi B, Tei F (2017) Non-chemical weed management strategies in minor crops: a review. Crop Prot 96:44–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2017.01.012

Pe’er G, Bonn A, Bruelheide H, Dieker P, Eisenhauer N et al (2020) Action needed for the EU Common Agricultural Policy to address sustainability challenges. People and Nature 2(2):305–316. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10080

Pe’er G, Lakner S, Müller R, Passoni G, Bontzorlos V et al (2017) Is the CAP Fit for purpose? An evidence-based fitness-check assessment.

Pe’er G, Zinngrebe Y, Moreira F, Sirami C, Schindler S et al (2019). A greener path for the EU Common Agricultural Policy. Science 365(6452):449–451. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax3146

Pecio A, Jarosz Z (2016) Long-term effects of soil management practices on selected indicators of chemical soil quality. Acta Agrobotanica 69(2):1–18. https://doi.org/10.5586/aa.1662

Petit S, Cordeau S, Chauvel B, Bohan D, Guillemin JP et al (2018) Biodiversity-based options for arable weed management. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 38(5). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-018-0525-3

Pogue SJ, Kröbel R, Janzen HH, Beauchemin KA, Legesse G et al (2018) Beef production and ecosystem services in Canada’s prairie provinces: a review. Agric Syst 166:152–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2018.06.011

Preissel S, Reckling M, Schläfke N, Zander P (2015) Magnitude and farm-economic value of grain legume pre-crop benefits in Europe: a review. Field Crop Res 175:64–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2015.01.012

Prevedello JA, Almeida-Gomes M, Lindenmayer DB (2017) The importance of scattered trees for biodiversity conservation: a global meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Ecology 55:205–214

Qiao C, Liu L, Hu S, Compton JE, Greaver TL, Li Q (2015) How inhibiting nitrification affects nitrogen cycle and reduces environmental impacts of anthropogenic nitrogen input. Glob Change Biol 21(3):1249–1257. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12802

Quemada M, Baranski M, Nobel-de Lange MNJ, Vallejo A, Cooper JM (2013) Meta-analysis of strategies to control nitrate leaching in irrigated agricultural systems and their effects on crop yield. Agr Ecosyst Environ 174:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2013.04.018

Ren F,, Sun N, Xu M, Zhang X, Wu L et al (2019) Changes in soil microbial biomass with manure application in cropping systems: a meta-analysis. Soil and Tillage Research 194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2019.06.008

Riffell S, Verschuyl J, Miller D, Wigley TB (2011) A meta-analysis of bird and mammal response to short-rotation woody crops. GCB Bioenergy 3(4):313–321. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1757-1707.2010.01089.x

Rockström J, Williams J, Daily G, Noble A, Matthews N et al (2017) Sustainable intensification of agriculture for human prosperity and global sustainability. Ambio 46(1):4–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0793-6

Rosa-Schleich J, Loos J, Mußhoff O, Tscharntke T (2019) Ecological-economic trade-offs of diversified farming systems – a review. Ecol Econ 160:251–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.03.002

Rowen EK, Regan KH, Barbercheck ME, Tooker JF (2020) Is tillage beneficial or detrimental for insect and slug management? A meta-analysis. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2020.106849

Sainju UM (2016) A global meta-analysis on the impact of management practices on net global warming potential and greenhouse gas intensity from cropland soils. PLoS ONE 11(2):1–26. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0148527

Sajeev EP, Winiwarter W, Amon B (2018) Greenhouse gas and ammonia emissions from different stages of liquid manure management chains: abatement options and emission interactions. J Environ Qual 47(1):30–41. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2017.05.0199

Samaniego L, Thober S, Kumar R, Wanders N, Rakovec O et al (2018) Anthropogenic warming exacerbates European soil moisture droughts. Nat Clim Chang 8(5):421–426. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0138-5

Sánchez B, Álvaro-Fuentes J, Cunningham R, Iglesias A (2016) Towards mitigation of greenhouse gases by small changes in farming practices: understanding local barriers in Spain. Mitig Adapt Strat Glob Change 21(7):995–1028. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-014-9562-7

Sanchis E, Calvet S, Prado A, Estellés F (2019) A meta-analysis of environmental factor effects on ammonia emissions from dairy cattle houses. Biosys Eng 178:176–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2018.11.017

Sanz-cobena A, Lassaletta L, Aguilera E, Prado A, Garniere J, Billen G (2016) Agriculture, ecosystems and environment strategies for greenhouse gas emissions mitigation in Mediterranean agriculture : a review. Agr Ecosyst Environ 238:5–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2016.09.038

Scheper J, Holzschuh A, Kuussaari M, Potts SG, Rundlöf M, Smith HG, Kleijn D (2013) Environmental factors driving the effectiveness of European agri-environmental measures in mitigating pollinator loss - a meta-analysis. Ecol Lett 16(7):912–920. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12128

Schlaich AE, Klaassen RHG, Bouten W, Both C, Koks BJ (2015) Testing a novel agri-environment scheme based on the ecology of the target species. Montagu’s Harrier Circus Pygargus Ibis 157(4):713–721. https://doi.org/10.1111/ibi.12299

Schumacher I (2019) Climate policy must favour mitigation over adaptation. Environ Resource Econ 74(4):1519–1531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-019-00377-0

Scohier A, Dumont B (2012) How do sheep affect plant communities and arthropod populations in temperate grasslands? Animal 6(7):1129–1138. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1751731111002618

Seibold S, Gossner MM, Simons NK, Blüthgen N, Müller J et al (2019) Arthropod decline in grasslands and forests is associated with landscape-level drivers. Nature 574(7780):671–674. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1684-3

Seppelt R, Arndt C, Beckmann M, Martin EA, Hertel TW (2020) Deciphering the biodiversity–production mutualism in the global food security debate. Ecol Evol 35(11):1011–1020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2020.06.012

Seufert V, Ramankutty N (2017) Many shades of gray—the context-dependent performance of organic agriculture. Science Advances 3(3). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1602638

Shackelford G, Steward PR, Benton TG, Kunin WE et al (2013) Comparison of pollinators and natural enemies: a meta-analysis of landscape and local effects on abundance and richness in crops. Biol Rev 88(4):1002–1021. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12040

Shackelford G. E. Kelsey R. & Dicks L. V. (2019). Effects of cover crops on multiple ecosystem services: ten meta-analyses of data from arable farmland in California and the Mediterranean. Land Use Policy, 88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104204

Shrestha BM, Chang SX, Bork EW, Carlyle CN (2018) Enrichment planting and soil amendments enhance carbon sequestration and reduce greenhouse gas emissions in agroforestry systems: a review. Forests 9(6):1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9060369

Skaalsveen K, Ingram J, Clarke LE (2019) The effect of no-till farming on the soil functions of water purification and retention in north-western Europe: a literature review. Soil and Tillage Research 189(January):98–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2019.01.004

Snyder H (2019) Literature review as a research methodology: an overview and guidelines. J Bus Res 104:333–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039

Stahlheber KA, D’Antonio CM (2013) Using livestock to manage plant composition: a meta-analysis of grazing in California Mediterranean grasslands. Biol Cons 157:300–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2012.09.008

Staton T, Walters RJ, Smith J, Girling RD (2019) Evaluating the effects of integrating trees into temperate arable systems on pest control and pollination. Agricultural Systems 176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2019.102676

Sun W, Canadell JG, Yu L, Yu L, Zhang W et al (2020) Climate drives global soil carbon sequestration and crop yield changes under conservation agriculture. Glob Change Biol 26(6):3325–3335. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15001

Tanveer M, Anjum SA, Hussain S, Cerdà A, Ashraf U (2017) Relay cropping as a sustainable approach: problems and opportunities for sustainable crop production. Environ Sci Pollut Res 24(8):6973–6988. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-017-8371-4

Ti C, Xia L, Chang SX, Yan X (2019) Potential for mitigating global agricultural ammonia emission: a meta-analysis. Environ Pollut 245:141–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2018.10.124

Tsonkova P, Böhm C, Quinkenstein A, Freese D (2012) Ecological benefits provided by alley cropping systems for production of woody biomass in the temperate region: a review. Agrofor Syst 85(1):133–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-012-9494-8

Tully K, Ryals R (2017) Nutrient cycling in agroecosystems: balancing food and environmental objectives. Agroecol Sustain Food Syst 41(7):761–798. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2017.1336149

van Eeden LM, Crowther MS, Dickman CR, Macdonald DW, Ripple WJ, Ritchie EG, Newsome TM (2018) Managing conflict between large carnivores and livestock. Conserv Biol 32(1):26–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12959

Van Leeuwen C, Pieri P, Gowdy M, Ollat N, Roby JP (2019) Reduced density is an environmental friendly and cost effective solution to increase resilience to drought in vineyards in a context of climate change. Oeno One 53(2):129–146

Verret V, Gardarin A, Pelzer E, Médiène S, Makowski D, Valantin-Morison M (2017) Can legume companion plants control weeds without decreasing crop yield? A meta-analysis. Field Crop Res 204:158–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2017.01.010

Visconti P, Elias V, Sousa Pinto I, Fischer M, Ali-Zade V et al (2018) Chapter 3: status, trends and future dynamics of biodiversity and ecosystems underpinning nature’s contributions to people. In M. Rounsevell, M. Fischer, A. Torre-Marin Rando, & A. Mader (Eds) The IPBES regional assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services for Europe and Central Asia (pp 187–382). Secretariat of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.32374288

Walker LK, Morris AJ, Cristinacce A, Dadam D, Grice PV, Peach WJ (2018) Effects of higher-tier agri-environment scheme on the abundance of priority farmland birds. Anim Conserv 21(3):183–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/acv.12386

Wang Y, Dong H, Zhu Z, Gerber PJ, Xin H et al (2017) Mitigating greenhouse gas and ammonia emissions from swine manure management: a system analysis. Environ Sci Technol 51(8):4503–4511. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b06430

Warner D, Tzilivakis J, Green A, Lewis K (2017) Prioritising agri-environment options for greenhouse gas mitigation. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management 9(1):104–122. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCCSM-04-2015-0048

Webber H, Lischeid G, Sommer M, Finger R, Nendel C et al (2020) No perfect storm for crop yield failure in Germany. Environmental Research Letters 15(104012). https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aba2a4

Wittstock F, Paulus A, Beckmann M, Hagemann N, Baaken M (2022) Understanding farmers’ adoption of agri-environmental schemes: a case study from Saxony. Manuscript submitted for publication, Germany

Wójcik-Gront E (2020) Analysis of sources and trends in agricultural GHG emissions from annex I countries. Atmosphere 11(4):392. https://doi.org/10.3390/ATMOS11040392

Wortman SE (2016) Weedy fallow as an alternative strategy for reducing nitrogen loss from annual cropping systems. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 36(4). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-016-0397-3

Xu S, Jagadamma S, Rowntree J (2018) Response of grazing land soil health to management strategies: a summary review. Sustainability (switzerland) 10(12):1–26. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124769

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Luis Lassaletta.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions