Abstract

Coffee cultivation in Central America provides goods and services at local, national, and international levels. Climate change is likely to affect the magnitude and continuity of these benefits by reducing the land suitability for coffee cultivation. To quantify the impacts of climate change on land suitability, we use the Bayesian network model Agroecological Land Evaluation for Coffea arabica L. (ALECA) and estimate the land suitability for coffee production in 2000, 2050, and 2080 under three climate change scenarios based on relative concentration pathways (RCPs) 2.6, 4.5, and 8.5. Results indicate that even under the less severe climate scenarios, over half of the current coffee area in Central America will experience a decline in its land suitability for coffee production, from excellent or good to moderate and marginal, and that the change will not happen in the more distant future of 2080, but by 2050. Under RCP 8.5, most coffee areas become of marginal and moderate suitability. The findings show that the continuity of coffee cultivation in a large portion of coffee areas in Central America is under threat and that farmers and policy-makers should develop adaptation portfolios for their farms and regions in a timely manner.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the last two decades, the coffee sector in Central America has experienced low prices and outbreaks of coffee rust, crises that have threatened the sustainability of coffee production (Avelino et al. 2015; CEPAL 2002; PROMECAFE 2018). Climate models project drier and warmer climate conditions in the Northern, and wetter conditions in the Southern, areas of Central America (Hidalgo et al. 2017), which will affect the climate suitability for coffee (Coffea arabica L.). The continued change in climate is likely to exacerbate existing problems in the coffee sector and create new ones, making it more difficult to sustain its production (Eakin et al. 2005; Frank et al. 2011; Reyer et al. 2017).

One option to explore the impacts of climate change on coffee yields and production across coffee regions would be to use sophisticated scientific tools such as crop models (Van Noordwijk and Lusiana 1998; van Oijen et al. 2010a). These models can provide a detailed assessment of the threat; however, coffee crop models are still limited in their ability to simulate coffee production beyond the plot scale, and many high-resolution data would be necessary as inputs, which are not readily available (van Oijen et al. 2010b). Thus, it is currently not possible to represent the existing complexity and variety of coffee systems with crop models at the spatial level required (Jose et al. 2004; Rao et al. 1997; Roupsard et al. 2009). Land evaluation is an alternative approach for assessing spatially explicit changes in coffee production suitability due to changes in climatic, soil, and topography-related factors (Brown et al. 2011; Lara-Estrada et al. 2017; Manandhar et al. 2014; Mighty 2015). Early warnings on expected changes in land suitability for coffee will enable farmers and agronomists to improve adaptation decisions and the planning of longer-term investments.

Other previous studies have employed species distribution models to address the effect of climate change on climate suitability for coffee cultivation, using only climate data and the location of coffee areas (Chemura et al. 2015; Ovalle-Rivera et al. 2015; Schroth et al. 2014). These types of models were developed to study the dispersion patterns of wild species in nature using presence-absence data (Convertino et al. 2014; Guillera-Arroita et al. 2014; Phillips et al. 2006; Yackulic et al. 2013). Global studies indicate that in about half of the current coffee area, the climate will become less suitable for cultivation in the future (Bunn et al. 2014; Ovalle-Rivera et al. 2015). As a solution, these authors propose to shift the current coffee areas to higher altitudes to overcome climate change alteration. However, if other agroecological factors like soils, landforms, or land use are not considered, moving coffee areas to climatically more suitable areas may either not be possible due to land-use conflicts or not advisable due to unsuitable soil or landform conditions. Considering all relevant factors is necessary for actual agricultural planning (FAO 1976; McRae et al. 1981; Mighty 2015; Nzeyimana et al. 2014).

To address this gap, we used the Bayesian network model Agroecological Land Evaluation for Coffea arabica L. (ALECA) to evaluate the suitability of a given piece of land for coffee cultivation based on climate, soil, and landform information (Lara-Estrada et al. 2017). The model was specifically developed based on parameters reported in the coffee literature and empirical data and has been used to evaluate the current conditions for coffee production in Central America. In this paper, we assess the impact of climate change on land suitability for coffee cultivation in Central America with consideration of soil and landform factors. Furthermore, we briefly discuss the land evaluation approach in agricultural planning and propose adaptation strategies for those regions where a considerable loss of land suitability for coffee cultivation is expected in the future.

Methods

Study area

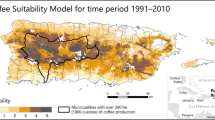

Our study covers the coffee areas in all coffee-producing countries of Central America. Guatemala has the largest coffee area, followed by Honduras, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Costa Rica, and Panama (Fig. 1) (PROMECAFE 2018). While the region contributes only about 10% to worldwide coffee production, the quality of the coffee is well appreciated in the coffee business (ICO 2015; McCook 2017). Both coffee production quantity and quality determine farmers’ income in the market (Adams and Roldan 1980; Bolwig and You 2007).

The region has tropical and subtropical conditions and wet (rainy) and dry seasons with some variations in duration and intensity depending on the location resulting from the oceanic influence and topography. Precipitation is the climatic variable with the highest variability, temperature variations for a given location are small during the year. The higher temperature changes are observed across altitudes (Imbach et al. 2017; Taylor and Alfaro 2005). Farmers cultivate coffee in the region under diverse agroecological conditions and production systems such as organic/conventional, low/high intensification, and full-sun monocrop/agroforestry (Blanco and Aguilar 2015; Haggar et al. 2011; Infante-Amate and Picado 2018; Meylan et al. 2013; Muschler 2001; Somarriba et al. 2004). Regarding the aptitude of the region for coffee cultivation, land suitability evaluations indicate that about 59% of the region’s coffee areas can be considered moderately to very good for coffee cultivation, and 14% as optimal (excellent); Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Honduras have the highest regional shares of optimal areas (Lara-Estrada et al. 2017).

The model ALECA

Land evaluation systems in agriculture rate the biophysical qualities of the land for crop production, and because of their simplicity and explicit nature serve as tools for planning and management at local and national levels (Brown et al. 2011; Manandhar et al. 2014; McRae et al. 1981). ALECA is a Bayesian network (BN) model composed of two parts, (1) a graphical structure that consists of a set of agroecological variables linked by arcs, where the links define the conditional dependencies between variables; and 2) conditional probability tables that quantify the dependency between variables (Fig. 2). In BNs, the graphical structure and conditional probability tables can be determined by implementing machine learning algorithms from data, using literature, expert elicitations, or a combination (Aguilera et al. 2011; Marcot 2012; Rodorff et al. 2018). Literature and machine learning were used for ALECA (Lara-Estrada et al. 2017).

The graphical structure of the Bayesian network model ALECA (Lara-Estrada et al. 2017). The model infers the suitability at three levels: single variable suitability, component suitability (climate, landform, and soil), and overall land suitability for coffee. See Lara-Estrada et al. (2017) for the suitability functions for soil and landform variables

ALECA evaluates land suitability based on the agroecological variables mean annual temperature [°C], annual precipitation [mm], dry season length [months], slope [%], aspect [cardinal direction], pH in H20, cation exchange capacity [Meq 100 g−1], and soil texture [categorical]. The variables were selected based on the results reported in the literature, correlations between variables, and data availability (Lara-Estrada et al. 2017). In ALECA, the suitability evaluation is inferred at three levels: variable, component, and land (Fig. 2). The variables are grouped into the components climate, soil, and landform. On Level 1, after entering the biophysical value of a given variable, a suitability function (S variables) assigns an individual suitability score to that value, ranging from 0 to 100%. Then, the suitability scores of each variable propagate to the corresponding component (Level 2), where an average component score is calculated. Finally, a weighted average is computed to estimate the overall land suitability (Level 3) from the suitability scores of the components climate (weight = 49%), soil (36%), and landform (15%) (Lara-Estrada et al. 2017).

Data

For current conditions (2000), the WorldClim dataset was used to obtain values for the climate variables (Chemura et al. 2015; Hijmans et al. 2005). Using the elevation data included in WorldClim, a spatial analysis was implemented to calculate the landform variables (ESRI 2012a, 2012b). The soil variables were obtained from the SoilGrids datasetFootnote 1 for 0–30 cm depth (Hengl et al. 2014). The individual datasets were merged into a single dataset at a 1 km × 1 km resolution.

To depict future climate conditions in 2050 and 2080, we used data from the model MPI-ESM-LR (ECHAM5) of the Max Planck Institute driven by the relative concentration pathway (RCP) scenarios 2.6, 4.5, and 8.5 (Jungclaus et al. 2006; Ramírez and Jarvis 2008). The data were downloaded at 30 s resolution (~1 km) (Ramirez-Villegas and Jarvis 2010) from the CCAFS GCM data portalFootnote 2. The MPI-ESM-LR was chosen because its performance in the study region was better than the average performance of 20 other climate models (Conde 2011; Fuentes-Franco et al. 2015; Maloney et al. 2013; Schaller et al. 2011). All modeling and data only cover the coffee areas in the study region.

Assumptions

We assumed that soil and landform variables would remain constant over time. Even though ALECA as a BN model can deal with data uncertainty (Aguilera et al. 2011; Lara-Estrada et al. 2018, 2017), we assumed no uncertainty in the input data to simplify the analysis. Coffee areas correspond to country coffee maps from the period 2010–2013 (Fig. 1) and are taken to portray the area for the year 2000 in the modeling. Because most of the coffee areas in the region are planted with Arabica varieties, and we were not able to extract non-Arabica areas, we assumed all coffee areas were planted with Arabica varieties. We assume that all Arabica varieties have the same suitability response to the agroecological variables. Even though the ALECA model does not consider interactions between agroecological variables and therefore cannot account for potential complementary or compensatory effects, the model performed very well in evaluating the current land suitability for coffee cultivation in the study region (Lara-Estrada et al. 2017).

Estimating land suitability

We inferred the land suitability (LS) for coffee cultivation for coffee areas under current and future climate conditions. Possible values for LS range from 0 to 100%, with 100% denoting the highest suitable value. In addition, a categorical land suitability scale was used to put the values into perspective: ≤60% = unsuitable, > 60% = marginal, > 75% = moderate, > 85% = good, >90% = excellent.

We also estimated the rate of change of LS under current and future climate conditions for the coffee areas. For this, we used the rate of change used by the FAO to depict changes in the forest coverage between periods (Puyravaud 2003; Velázquez et al. 2002). In this study, the equation depicts the rate of change (Rc) of coffee areas with a given land suitability between the years 2000, 2050, and 2080.

where A2 and A1 are the percent of areas with a given LS-score value at different years, and n is the number of years between the two years under comparison.

Results

In our simulations, the land suitability for coffee cultivation decreased under all climate change scenarios in Central America. About half of the areas currently classified as excellent or good were downgraded to moderate or marginal under the less severe scenarios RCP 2.6 and 4.5, and they almost disappeared under the most severe scenario, RCP 8.5.

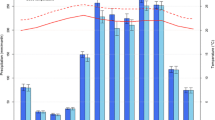

RCPs 2.6 and 4.5 show a similar trend in land suitability changes over time, but losses in land suitability scores are a little higher in RCP 4.5 (Fig. 3). In both scenarios, most changes occurred between 2000 and 2050, with only minor changes between 2050 and 2080. For RCP 8.5, the suitability losses were much higher (Fig. 3A) and more constant over time (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, the cumulative LS distribution functions reveal non-linear impacts of climate change across land qualities. The observed variations in the LS changes between periods are mainly caused by temperature and precipitation changes depicted in the CMIP5 data. For surface temperature, there is an overall rise close to the middle of the century in all RCPs, followed by an abated warming in RCP 2.6, a slightly abated warming in RCP 4.5, and a marked continuation of warming in RCP 8.5 until 2080 (Knutti & Sedláček, 2012). See Online Resource 1 for additional results on regional LS.

Current and future land suitability of coffee areas (Coffea arabica L.) under three scenarios of climate change in Central America. The data shown in panels A and B are the same; in A, the differences between climate change scenarios is highlighted; in B, the differences between the different time periods. Most changes occur between 2000 and 2050 for RCPs 2.6 and 4.5; for RCP 8.5, suitability losses are higher and more constant over time. Land suitability classes: ≤60% = unsuitable, >60% = marginal, >75% = moderate, >85% = good, >90% = excellent

The unequal impacts of climate change on land suitability in the different periods are also shown in Table 1. The average annual rates of change (Rc) in LS scores are generally higher between 2000 and 2050 than between 2050 and 2080. In addition, the Rc shows a particular pattern of changes across different land qualities. Areas with 70% ≤ LS > 90% have the highest rates under all the RCPs and periods. Negative changes occur in areas with LS > 80% and positives in areas with LS scoring between 60 and 80%. Areas with LS scores below 60% display positive or negative changes depending on RCP and period. The Rc can help identify which LS coffee areas will be more affected and where actions need to be focused on coping with the adverse effects.

In 2000, 145,639 ha of coffee areas in Central America were scored excellent, 235,415 ha good, 547,897 ha moderate, 130,793 ha marginal, and 18 ha unsuitable (Fig. 4, first map). The absolute LS losses of most coffee areas remain below 15% under RCPs 2.6 and 4.5 but reach 37% under RCP 8.5 (Fig. 4, other maps). Most coffee areas follow the general trend of increasing losses of land suitability from RCP 2.6 to 8.5 and 2000 to 2080, but there are exceptions in each country. Some coffee areas in Western Honduras, e.g., show higher losses under RCP 2.6 than under RCP 4.5 in 2050, some areas in Costa Rica experience an LS-score loss in 2050 but improve by 2080, and a fraction of coffee areas will experience positive changes under all RCPs and periods (green areas in Fig. 4). This is particularly promising for some areas in Guatemala, Honduras, and Costa Rica. See Online Resources 1 for regional maps on LS changes.

Table 2 provides a comprehensive overview of all estimated LS changes. Coffee areas classified as excellent in the year 2000 shrink by 56%, 63%, and 93% under the three different RCP scenarios, respectively. Most of these areas downgrade to the moderate or marginal categories. At the other end of the suitability scale, the picture is different: between 89 and 94% of currently rated marginal areas remain marginal under the three RCPs. Some upgrades were observed from marginal or moderate to excellent or good but remained below 5%. In all periods for RCP 2.6 and 4.5, 71% of areas currently rated unsuitable for coffee production experience an upgrade to marginal, and for RCP 8.5 to moderate, but since the actual unsuitable area is only 18 ha, the change is irrelevant to the whole picture. These improvements are observed in areas where the current low suitability is caused by colder conditions, shorter dry seasons, higher annual precipitation values, or a combination of all. Changes in climate to warmer and drier conditions improve the climate suitability for coffee in these areas. Areas that remain marginal or unsuitable are already warm and dry, so climate change does not improve the conditions for coffee production (Hidalgo et al. 2017).

We can thus observe changes in both directions on the suitability scale, but changes are negative for a much larger area, with a decrease in highly suitable areas and an increase in moderately and marginally suitable areas. Therefore, the quantity and quality of the regional coffee production are under threat.

A closer look at the changes in suitability for each variable in the climate component reveals that mean temperature suitability for coffee cultivation experienced the highest losses, from 10.24% under RCP 2.6 in 2050 to 47.27% in RCP 8.5 in 2080 (Table 3). The average precipitation suitability variability is much lower, with losses from 0.36 to 6.17% and lowest in dry season length suitability, ranging from 0.55 to − 1.17%. However, even if the mean changes in precipitation and dry season length are small compared to temperature, the standard deviation, minimum, and maximum of the three distributions are very similar. This suggests that in some areas, the positive or negative changes in precipitation and dry season length will be much larger than the average, confirming our previous finding that some areas will experience land suitability changes in opposition to the regional average (cf. Fig. 4).

We looked at six representative coffee zones in Central America (described in detail in Lara-Estrada et al. 2017) to have a clearer insight into the dynamics of LS changes at the local level. Currently, the coffee area Tarrazú is considered excellent, Jinotega and Márcala as good, and El Paraíso, Masatepe, and Turrialba as moderate (Bertrand et al. 2006; Haggar et al. 2011; Lara-Estrada et al. 2017; Teuber 2009). Figure 5 shows that most zones experience a downgrade in LS from 2000 to 2050 and 2080, but the magnitude differs between selected zones. Tarrazú, Jinotega, and Márcala downgrade the least with less than 4.5% on average. Tarrazú and Márcala may even experience some upgrades in LS under the less severe scenarios of RCP 2.6 and 4.5. Turrialba and Masatepe incur the highest losses in LS under the three RCPs, by 6–12% on average. Under RCP 8.5, all locations except Tarrazú experience considerable LS reductions, and some zones become marginal by 2080. These insights may enable local farmers, stakeholders, and institutions involved in coffee production to develop adaptation plans customized for every region.

The zones El Paraiso and Turrialba show high internal variability in LS scores, whereas others like Tarrazú or Masatepe have more homogenous profiles. Looking at the two representative zones in Nicaragua, Masatepe (461 m.a.s.l.) and Jinotega (1091 m.a.s.l.), one can also observe how the LS profiles, composed of soil, landform, and climate components, influence the future dynamic of LS-score changes. The landform and soil conditions are better suited for coffee cultivation in Masatepe than in Jinotega because the region has flatter slopes and better physical and chemical soil properties (e.g., slope 2.17 ± 1.6% in Masatepe vs. 6.77 ± 4.06% in Jinotega; CEC 27.11 ± 1.72 vs. 16.50 ± 1.90 Meq 100 g−1). However, climatic conditions in Masatepe are less suitable for coffee because temperatures are higher and the dry season more prolonged (mean temperature 24.26 ± 0.35 in Masatepe vs. 19.85 ± 0.96 °C in Jinotega; dry season length 5 ± 0 vs. 3.03 ± 0.2 months) (Haggar et al. 2011; Hengl et al. 2014; Hijmans et al. 2005). Coffee plantations in Masatepe thus experience temperature and water stress during the year and particularly in the dry season, which can lead to abortion or abnormalities in the flowering and fruiting stages, which impacts productivity and coffee quality. In the long term, these climatic stresses lead to a reduced life expectancy of coffee plants (DaMatta and Ramalho 2006; Melke and Fetene 2014); and therefore, coffee plantations may have to be replanted more frequently. This explains why climate change, even in the more benign RCP scenarios, leads to a rapid loss of land suitability scores in zones like Masatepe.

Discussion

Given the magnitude of expected LS losses even until 2050, effective and timely adaptations are needed to sustain coffee production in Central America. Some authors suggest moving the coffee areas to higher altitudes or other areas that will become suitable in the future (Läderach et al. 2010; Zullo et al. 2011). However, considering the financial state of the farmers and the coffee sector as a whole after the series of crises in the last years and decades, the existing land-rights issues, and national land-use regulations, this suggestion may not be easily realized (Boucher et al. 2005; Broegaard 2010; Charlip 1999; Zeledon and Kelly 2009). A more feasible solution for small- and medium-scale farmers in the region is to increase current coffee areas’ resilience. Haggar and Schepp (2012), for example, mention a series of adaptation strategies that include technical (e.g., agroforestry and income diversification), financial (climate insurance), and organizational aspects (joint efforts and planning) that coffee farmers and farmers’ organizations can consider and implement to improve their level of resilience to climate change.

The effects of climate change can also be alleviated by a change in farming practices, such as adjusting the shade of trees in the coffee plantations to improve the microclimate and soil conditions, irrigation, fertilization, soil conservation practices, or better-adapted coffee varieties (Meylan et al. 2017; de Souza et al. 2012; Vaast et al. 2016). Agroforestry is already used in the coffee areas in the region as a strategy to improve microclimatic and soil conditions under suboptimal conditions (areas at low altitudes) (Harvey et al. 2017), which explains the presence of a considerable proportion of the current coffee area under marginal LS conditions. Conservation practices of soil and water could be adopted to improve other biophysical conditions (Blanco and Aguilar 2015; Harvey et al. 2014), and the planting of coffee varieties better adapted to shade, drought, and warming conditions may improve the resilience of coffee farms under marginal and moderate LS conditions (Bertrand et al. 2011; Montagnon et al. 2012).

The selection of farming adaptation practices and final strategies at the farm level should be tailored to the region and reflect the severity of the expected changes (Vermeulen et al. 2013). Coffee farmers in areas where only a slight decrease in land suitability is expected, like Tarrazú, Jinotega, and Marcala, may only need to adjust at a varietal, or shading, or intensification level. Farmers in coffee areas with medium LS losses may need to make further adjustments like introducing shade trees of higher economic value (producing timber and fruits), adding market value to the coffee (certification, postharvest processing), and improving the efficiency of farming practices. In the areas with the highest LS losses, where climate will become unsuitable for Coffea arabica L. cultivation, changing to other crops like Coffea canephora (robusta coffee) or cocoa is an option that may allow the farmers to continue cultivating without changing their whole operations.

Climate change is expected to progressively increase the occurrence and severity of the most important pests and diseases like the coffee berry borer (Hypothenemus hampei) and the coffee rust (Hemileia vastatrix) over time (Jaramillo et al. 2011, 2009; Merle et al. 2020; Ward et al. 2017). Some even consider the past outbreak of coffee rust in Central America as an early warning of what may become more recurrent in the future (Avelino et al. 2015). On the other hand, the occurrence of diseases favored by cold conditions like leaf spot (Mycena citricolor) will probably decrease (Avelino et al. 2007). Adaptation strategies and practices need to be incorporated into farm planning, not only against latent threats like pests and diseases, but also for expected changes in biophysical conditions, price crises, local land-use changes, market or financial opportunities, and farmers’ socioeconomic conditions and preferences (Vega and Somarriba 2005; Waldick et al. 2017).

Land evaluations like the one we presented here can support the planning and decision-making processes at the farm, local, national, and regional levels (Bizikova et al. 2015). Stakeholders can use these results or even the model ALECA itself to explore how changes in the soil, landform, and climate variables affect the aptitude of their land for coffee cultivation instead of relying on general tendencies (Brown et al. 2011). At the governmental level, based on the rates of change, spatial distribution, and severity of the LS changes to be expected in the coffee areas in the Central America region, policies, and programs oriented to support the coffee farmers should include technical and financial tools as well as a legal framework for planning and implementing region-specific adaptation strategies. Finally, because of the magnitude of the changes in the land suitability across the coffee areas in the region, it is possible that even if all possible adaptation actions are implemented and coffee production continues in the region, the quantity and quality of the coffee will change.

Conclusions

The suitability of current coffee areas in Central America to produce coffee will decrease at an alarming rate under climate change. Highly suitable areas will decrease in size, while the size of only marginally suitable areas will increase. Under the most severe climate change scenario (RCP 8.5), most of the current coffee areas will become marginal or unsuitable for Coffea arabica L. cultivation. Given the expected speed of land suitability downgrades in the period 2000–2050 and the perennial nature of the coffee plant, adaptation actions need to be implemented urgently. They should be customized to the specific coffee areas and the expected changes there. High-resolution land evaluations like this one may support stakeholders in this endeavor by giving an estimation of not only the expected change in overall suitability for coffee cultivation but also of the single component changes that showcase what factors adaptation measures need to target to be most effective.

Change history

18 September 2021

Springer Nature’s version of this paper was updated to reflect the missing supplementary material.

References

Adams FG, Roldan RA (1980) An econometric approach to measuring the impact of primary commodity price fluctuations on economic development: coffee and Brazil, in: Commodity markets and Latin American development: a modeling approach. UMI 59–183. http://www.nber.org/chapters/c1753

Aguilera PA, Fernández A, Fernández R, Rumí R, Salmerón A (2011) Bayesian networks in environmental modelling. Environ Model Softw 26:1376–1388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2011.06.004

ANAM (2012) Áreas de café. Autoridad Nacional del Ambiente, Panama

Avelino J, Cabut S, Barboza B, Barquero M, Alfaro R et al (2007) Topography and crop management are key factors for the development of American leaf spot epidemics on coffee in Costa Rica. Phytopathology 97:1532–1542. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-97-12-1532

Avelino J, Cristancho M, Georgiou S, Imbach P, Aguilar L et al (2015) The coffee rust crises in Colombia and Central America (2008–2013): impacts, plausible causes and proposed solutions. Food Security 7:303–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-015-0446-9

Bertrand B, Vaast P, Alpizar E, Etienne H, Davrieux F et al (2006) Comparison of bean biochemical composition and beverage quality of Arabica hybrids involving Sudanese-Ethiopian origins with traditional varieties at various elevations in Central America. Tree Physiol 26:1239–1248. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/26.9.1239

Bertrand B, Alpizar E, Lara L, SantaCreo R, Hidalgo M et al (2011) Performance of Coffea arabica F1 hybrids in agroforestry and full-sun cropping systems in comparison with American pure line cultivars. Euphytica 181:147–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10681-011-0372-7

Bizikova L, Pintér L, Tubiello N (2015) Normative scenario approach: a vehicle to connect adaptation planning and development needs in developing countries. Reg Environ Chang 15:1433–1446. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-014-0705-x

Blanco R, Aguilar A (2015) Soil erosion and erosion thresholds in an agroforestry system of coffee (Coffea arabica) and mixed shade trees (Inga spp and Musa spp) in Northern Nicaragua. Agric Ecosyst Environ 210:25–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2015.04.032

Bolwig S, You L (2007) Quality or volume? An economic evaluation of coffee development strategies for Uganda. Dev Pract 17:433–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520701337285

Boucher SR, Barham BL, Carter MR (2005) The impact of “market-friendly” reforms on credit and land markets in Honduras and Nicaragua. World Dev 33:107–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.09.004

Broegaard RB (2010) Land access and titling in Nicaragua, in: Reader, T.S., Lundessor, C. (Eds.), The politics of possession. Wiley-Blackwell 142-161. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444322903.ch7.

Brown I, Poggio L, Gimona A, Castellazzi M (2011) Climate change, drought risk and land capability for agriculture: implications for land use in Scotland. Reg Environ Chang 11:503–518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-010-0163-z

Bunn C, Läderach P, Rivera OO, Kirschke D (2014) A bitter cup: climate change profile of global production of Arabica and Robusta coffee. Clim Chang 129:89–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-014-1306-x

CATIE, MAGFOR (2012) Elaboraciòn del mapa de cobertura cultivo de cafe de Nicaragua 2012 con base en imágenes de satelite landsat (Final Report). CATIE - MAGFOR, Managua, Nicaragua

CEPAL (2002) Centroamérica: el impacto de la caída de los precios del café, Serie estudios y perspectivas. CEPAL, México, DF. https://www.cepal.org/sites/default/files/publication/files/5016/S024278_es.pdf

Charlip JA (1999) “So that land takes on value”: coffee and land in Carazo, Nicaragua. Lat Am Perspect 26:92–105 (https://www.jstor.org/stable/2634039?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents)

Chemura A, Kutywayo D, Chidoko P, Mahoya C (2015) Bioclimatic modelling of current and projected climatic suitability of coffee (Coffea arabica) production in Zimbabwe. Reg Environ Chang 16:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-015-0762-9

Conde C (2011) Coping with climate change impacts on coffee and maize for peasants in Mexico, in: Brauch, H.G., Oswald Spring, Ú., Mesjasz, C., Grin, J., Kameri-Mbote, P., Chourou, B., Dunay, P., Birkmann, J. (Eds.), Coping with global environmental change, disasters and security, hexagon series on human and environmental security and peace. Springer Berlin Heidelberg 1067-1080. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-17776-7_65

Convertino M, Muñoz-Carpena R, Chu-Agor ML, Kiker GA, Linkov I (2014) Untangling drivers of species distributions: global sensitivity and uncertainty analyses of MaxEnt. Environ Model Softw 51:296–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2013.10.001

DaMatta FM, Ramalho JDC (2006) Impacts of drought and temperature stress on coffee physiology and production: a review. Braz J Plant Physiol 18:55–81. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1677-04202006000100006

de Souza HN, de Goede RGM, Brussaard L, Cardoso IM, Duarte EMG et al (2012) Protective shade, tree diversity and soil properties in coffee agroforestry systems in the Atlantic Rainforest biome. Agric Ecosyst Environ 146:179–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2011.11.007

Eakin H, Tucker CM, Castellanos E (2005) Market shocks and climate variability: the coffee crisis in Mexico, Guatemala, and Honduras. Mt Res Dev 25:304–309. https://doi.org/10.1659/0276-4741(2005)025[0304:MSACVT]2.0.CO;2

ESRI (2012a) Determining aspect [WWW Document]. ArcGIS Desktop Help 9.3. URL http://webhelp.esri.com/arcgisdesktop/9.3/index.cfm?TopicName=Determining_aspect (accessed 4.26.21)

ESRI (2012b) Calculating slope [WWW Document]. ArcGIS Desktop Help 9.3. URL http://webhelp.esri.com/arcgisdesktop/9.3/index.cfm?TopicName=Calculating_slope (accessed 4.26.21)

FAO (1976) A framework for land evaluation, Soils bulletin. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy

Frank E, Eakin H, López-Carr D (2011) Social identity, perception and motivation in adaptation to climate risk in the coffee sector of Chiapas, Mexico. Glob Environ Chang 21:66–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.11.001

Fuentes-Franco R, Coppola E, Giorgi F, Pavia EG, Diro GT et al (2015) Inter-annual variability of precipitation over Southern Mexico and Central America and its relationship to sea surface temperature from a set of future projections from CMIP5 GCMs and RegCM4 CORDEX simulations. Clim Dyn 45:425–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-014-2258-6

Guillera-Arroita G, Lahoz-Monfort JJ, Elith J (2014) Maxent is not a presence–absence method: a comment on Thibaud et al. Methods Ecol Evol 5, 1192–1197. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12252

Haggar J, Schepp K (2012) Coffee and climate change: impacts and options for adaption in Brazil, Guatemala, Tanzania and Vietnam (No. 4), NRI Working Paper Series: NRI, University of Greenwich, UK

Haggar J, Barrios M, Bolaños M, Merlo M, Moraga P et al (2011) Coffee agroecosystem performance under full sun, shade, conventional and organic management regimes in Central America. Agrofor Syst 82:285–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-011-9392-5

Harvey CA, Chacón M, Donatti CI, Garen E, Hannah L et al (2014) Climate-smart landscapes: opportunities and challenges for integrating adaptation and mitigation in tropical agriculture. Conserv Lett 7:77–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12066

Harvey CA, Martínez-Rodríguez MR, Cárdenas JM, Avelino J, Rapidel B et al (2017) The use of Ecosystem-based Adaptation practices by smallholder farmers in Central America. Agric Ecosyst Environ 246:279–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2017.04.018

Hengl T, de Jesus JM, MacMillan RA, Batjes NH, Heuvelink GBM et al (2014) SoilGrids1km — global soil information based on automated mapping. PLoS One 9:e105992. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0105992

Hidalgo HG, Alfaro EJ, Quesada-Montano B (2017) Observed (1970–1999) climate variability in Central America using a high-resolution meteorological dataset with implication to climate change studies. Clim Chang 141:13–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-016-1786-y

Hijmans RJ, Cameron SE, Parra JL, Jones PG, Jarvis A (2005) Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int J Climatol 25:1965–1978. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.1276

IAIP (2013) Mapa de áreas de café de Honduras. Instituto Nacional de Conservación y Desarrollo Forestal, Honduras.

ICAFE (2013) Áreas de café. Instituto del Café de Costa Rica, Costa Rica

ICO (2015) Historical data on the global coffee trade [WWW Document]. URL http://www.ico.org/new_historical.asp?section=Statistics (accessed 9.11.15)

Imbach P, Beardsley M, Bouroncle C, Medellin C, Läderach P et al (2017) Climate change, ecosystems and smallholder agriculture in Central America: an introduction to the special issue. Clim Chang 141:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-017-1920-5

Infante-Amate J, Picado W (2018) Energy flows in the coffee plantations of Costa Rica: from traditional to modern systems (1935–2010). Reg Environ Chang 18:1059–1071. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-017-1263-9

Jaramillo J, Chabi-Olaye A, Kamonjo C, Jaramillo A, Vega FE et al (2009) Thermal tolerance of the coffee berry borer Hypothenemus hampei: predictions of climate change impact on a tropical insect pest. PLoS One 4:e6487. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0006487

Jaramillo J, Muchugu E, Vega FE, Davis A, Borgemeister C et al (2011) Some like it hot: the influence and implications of climate change on coffee berry borer (Hypothenemus hampei) and coffee production in East Africa. PLoS One 6:e24528. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0024528

Jose S, Gillespie AR, Pallardy SG (2004) Interspecific interactions in temperate agroforestry. Agrofor Syst 61:237–255. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:AGFO.0000029002.85273.9b

Jungclaus JH, Keenlyside N, Botzet M, Haak H, Luo J-J et al (2006) Ocean circulation and tropical variability in the coupled model ECHAM5/MPI-OM. J Clim 19:3952–3972. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI3827.1

Läderach P, Lundy M, Jarvis A, Ramirez J, Portilla EP et al (2010) Predicted impact of climate change on coffee supply chains, in: Leal Filho, W. (Ed.), The economic, social and political elements of climate change, Climate Change Management. Springer Berlin Heidelberg 703-723. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-14776-0_42

Lara-Estrada L, Rasche L, Schneider UA (2017) Modeling land suitability for Coffea arabica L. in Central America. Environ Model Softw 95:196–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2017.06.028

Lara-Estrada L, Rasche L, Sucar LE, Schneider UA (2018) Inferring missing climate data for agricultural planning using Bayesian networks. Land 7:4. https://doi.org/10.3390/land7010004

MAG (2010) Áreas de café. Ministerio de Agricultura y Ganadería, El Salvador

MAGA (2010) Áreas de café. Ministerio de Agricultura y Ganadería, Guatemala

Maloney ED, Camargo SJ, Chang E, Colle B, Fu R et al (2013) North American climate in CMIP5 experiments: Part III: assessment of twenty-first-century projections. J Clim 27:2230–2270. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-13-00273.1

Manandhar S, Pandey VP, Kazama F (2014) Assessing suitability of apple cultivation under climate change in mountainous regions of western Nepal. Reg Environ Chang 14:743–756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-013-0531-6

Marcot BG (2012) Metrics for evaluating performance and uncertainty of Bayesian network models. Ecol Model 230:50–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2012.01.013

McCook S (2017) Environmental history of coffee in Latin America. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.013.440

McRae SG, Stuart G, Burnham CP. Christopher P (1981) Land evaluation, monographs on soil survey. Clarendon Press ; Oxford University Press, Oxford : New York

Melke A, Fetene M (2014) Eco-physiological basis of drought stress in coffee (Coffea arabica, L.) in Ethiopia. Theor Exp Plant Physiol 26:225–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40626-014-0022-2

Merle I, Tixier P, Filho V, E de M, Cilas C, Avelino J (2020) Forecast models of coffee leaf rust symptoms and signs based on identified microclimatic combinations in coffee-based agroforestry systems in Costa Rica. Crop Prot 130:105046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2019.105046

Meylan L, Merot A, Gary C, Rapidel B (2013) Combining a typology and a conceptual model of cropping system to explore the diversity of relationships between ecosystem services: the case of erosion control in coffee-based agroforestry systems in Costa Rica. Agric Syst 118:52–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2013.02.002

Meylan L, Gary C, Allinne C, Ortiz J, Jackson L et al (2017) Evaluating the effect of shade trees on provision of ecosystem services in intensively managed coffee plantations. Agric Ecosyst Environ 245:32–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2017.05.005

Mighty MA (2015) Site suitability and the analytic hierarchy process: how GIS analysis can improve the competitive advantage of the Jamaican coffee industry. Appl Geogr 58:84–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2015.01.010

Montagnon C, Marraccini P, Bertrand B (2012) Breeding for coffee quality, In: Oberthür T, Läderach P, Cock JH (eds) Specialty coffee: managing quality. IPNI, Penang, Malaysia 89–117

Muschler RG (2001) Shade improves coffee quality in a sub-optimal coffee-zone of Costa Rica. Agrofor Syst:131–139. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010603320653

Nzeyimana I, Hartemink AE, Geissen V (2014) GIS-based multi-criteria analysis for Arabica coffee expansion in Rwanda. PLoS One 9:e107449. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0107449

Ovalle-Rivera O, Läderach P, Bunn C, Obersteiner M, Schroth G (2015) Projected shifts in Coffea arabica suitability among major global producing regions due to climate change. PLoS One 10:e0124155. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0124155

Phillips SJ, Anderson RP, Schapire RE (2006) Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol Model 190:231–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2005.03.026

PROMECAFE (2018) El estado actual de la Rentabilidad del café en Centroamérica. CABI, Guatemala

Puyravaud J-P (2003) Standardizing the calculation of the annual rate of deforestation. For Ecol Manag 177:593–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1127(02)00335-3

Ramírez J, Jarvis A (2008) High resolution statistically downscaled future climate surfaces. International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT); CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), Cali, Colombia

Ramirez-Villegas J, Jarvis A (2010) Downscaling global circulation model outputs: the delta method decision and policy analysis (Working Paper No. 1). CIAT, Cali, Colombia

Rao MR, Nair PKR, Ong CK (1997) Biophysical interactions in tropical agroforestry systems. Agrofor Syst 38:3–50. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005971525590

Reyer CPO, Adams S, Albrecht T, Baarsch F, Boit A et al (2017) Climate change impacts in Latin America and the Caribbean and their implications for development. Reg Environ Chang 17:1601–1621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-015-0854-6

Rodorff V, Steinmetz L, Mertens J, Siegmund-Schultze M, Köppel J (2018) Applying Bayesian networks to evaluate small-scale farmers’ perceptions of native reforestation practices in Brazil’s Caatinga biome. Reg Environ Chang 18:1983–1997. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-018-1370-2

Roupsard O, Gomez-Delgado F, Rapidel B, Le Maire G (2009) Why is agroforestry so challenging for modellers? How to conciliate complexity, interctions, accuracy and upscaling. A proposed strategy for agroforestry modelling., in: Rapidel, B., Roupsard, O., Navarro, M. (Eds.), Workshop Proceedings (25–29 February 2008), Technical Meetings No. 14. Presented at the Modelling Agroforestry Systems, CATIE, Costa Rica 69–80. https://agritrop.cirad.fr/553033/

Schaller N, Mahlstein I, Cermak J, Knutti R (2011) Analyzing precipitation projections: a comparison of different approaches to climate model evaluation. J Geophys Res 116. https://doi.org/10.1029/2010JD014963

Schroth G, Läderach P, Cuero DSB, Neilson J, Bunn C (2014) Winner or loser of climate change? A modeling study of current and future climatic suitability of Arabica coffee in Indonesia. Reg Environ Chang 15:1473–1482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-014-0713-x

Somarriba E, Harvey CA, Samper M, Anthony F, González J et al (2004) Biodiversity conservation in neotropical coffee (Coffea arabica L.) plantations, in: Schroth, G., da Fonseca, G., Harvey, C., Gascon, C., Vasconcelos, H., Izac, A. (Eds.), Agroforestry and biodiversity conservation in tropical landscapes. Island Press, Washington, DC, USA 198–226. https://islandpress.org/books/agroforestry-and-biodiversity-conservation-tropical-landscapes

Taylor MA, Alfaro EJ (2005) Central America and the Caribbean, Climate of, in: Oliver, J. (Ed.), Encyclopedia of World Climatology, Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series. Springer, Dordrecht, Netherlands 183–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-3266-8_37

Teuber R (2009) Café de Marcala - Honduras’ GI approach to achieving reputation in the coffee market. Estey Centre J Int Law Trade Policy 10:131–148. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.48798

Vaast P, Harmand JM, Rapidel B, Jagoret P, Deheuvels O (2016) Coffee and cocoa production in Agroforestry—a climate-smart agriculture model, in: Climate change and agriculture worldwide. Springer, Dordrecht, Netherlands. 16 209–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-7462-8_16

van Noordwijk M, Lusiana B (1998) WaNuLCAS, a model of water, nutrient and light capture in agroforestry systems. Agrofor Syst 43:217–242. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026417120254

van Oijen M, Dauzat J, Harmand J-M, Lawson G, Vaast P (2010a) Coffee agroforestry systems in Central America: II. Development of a simple process-based model and preliminary results. Agrofor Syst 80:361–378. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-010-9291-1

van Oijen M, Dauzat J, Harmand J-M, Lawson G, Vaast P (2010b) Coffee agroforestry systems in Central America: I. A review of quantitative information on physiological and ecological processes. Agrofor Syst 80:341–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-010-9294-y

Vega M, Somarriba E (2005) Planificación agroforestal de fincas cacaoteras orgánicas del Alto Beni, Bolivia. Agroforestería en las Américas 43–44:20–26 http://repositorio.bibliotecaorton.catie.ac.cr/handle/11554/7614

Velázquez A, Mas JF, Gallegos JRD, Saucedo RM, Alcántara PC et al (2002) Patrones y tasas de cambio de uso del suelo en México. Gaceta Ecológica 62:21–37 http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=53906202

Vermeulen SJ, Challinor AJ, Thornton PK, Campbell BM, Eriyagama N et al (2013) Addressing uncertainty in adaptation planning for agriculture. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110:8357–8362. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1219441110

Waldick R, Bizikova L, White D, Lindsay K (2017) An integrated decision-support process for adaptation planning: climate change as impetus for scenario planning in an agricultural region of Canada. Reg Environ Chang 17:187–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-016-0992-5

Ward R, Gonthier D, Nicholls C (2017) Ecological resilience to coffee rust: varietal adaptations of coffee farmers in Copán, Honduras. Agroecol Sustain Food Syst 41:1081–1098. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2017.1345033

Yackulic CB, Chandler R, Zipkin EF, Royle JA, Nichols JD et al (2013) Presence-only modelling using MAXENT: when can we trust the inferences? Methods Ecol Evol 4:236–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210x.12004

Zeledon EB, Kelly NM (2009) Understanding large-scale deforestation in southern Jinotega, Nicaragua from 1978 to 1999 through the examination of changes in land use and land cover. J Environ Manage Environ Landscape Change: Addressing an interdisciplinary agenda 90:2866–2872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.03.016

Zullo J, Pinto HS, Assad ED, de Ávila AMH (2011) Potential for growing Arabica coffee in the extreme south of Brazil in a warmer world. Clim Chang 109:535–548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-011-0058-0

Acknowledgements

This work was part of the doctoral research of LLE at the School of Integrated Climate System Sciences, University of Hamburg. It contributes to the Cluster of Excellence ‘CLICCS - Climate, Climatic Change, and Society’ and the Center for Earth System Research and Sustainability (CEN) of Universität Hamburg. We would further like to thank Dr. Jeremy Haggar and Dr. Christophe Montagnon for their comments on the early versions of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was primarily funded by the Cluster of Excellence Integrated Climate System Analysis and Prediction [Grant DFG-EXC177], Germany. Additional funding was received from the project CLICCS [ExNet-0025-Phae2-3] funded by the Initiative and Networking Fund of the Helmholtz Association.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Communicated by Jasper van Vliet

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(PDF 13.9 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lara-Estrada, L., Rasche, L. & Schneider, U.A. Land in Central America will become less suitable for coffee cultivation under climate change. Reg Environ Change 21, 88 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-021-01803-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-021-01803-0