Abstract

Increasing pressure on shared water resources has often been a driver for the development and utilisation of water resource models (WRMs) to inform planning and management decisions. With an increasing emphasis on regional decision-making among competing actors as opposed to top-down and authoritative directives, the need for integrated knowledge and water diplomacy efforts across federal and international rivers provides a test bed for the ability of WRMs to operate within complex historical, social, environmental, institutional and political contexts. This paper draws on theories of sustainability science to examine the role of WRMs to inform transboundary water resource governance in large river basins. We survey designers and users of WRMs in the Colorado River Basin in North America and the Murray-Darling Basin in southeastern Australia. Water governance in such federal rivers challenges inter-governmental and multi-level coordination and we explore these dynamics through the application of WRMs. The development pathways of WRMs are found to influence their uptake and acceptance as decision support tools. Furthermore, we find evidence that WRMs are used as boundary objects and perform the functions of ‘boundary work’ between scientists, decision-makers and stakeholders in the midst of regional environmental changes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Water resource models (WRMs) are frequently used to aid decision-making by capturing, communicating and translating knowledge of complex hydrologic and social systems. Abstract representations of these systems are created using equations and assumptions, along with spatially and temporally simplified data. WRMs are often used in contested situations with multiple interests where the saliency of policy insight they provide must be balanced with scientific credibility and perceived legitimacy of the knowledge they are built upon (Cash et al. 2003).

Management of shared water resources across multiple jurisdictions such as federal river basins is particularly complex (Garrick et al. 2014) and challenges are exacerbated in drought-prone regions or fully allocated rivers. Water governance paradigms such as integrated water resource management (IWRM) (GWP 2000) and water diplomacy (Islam and Susskind 2012) seek to improve dialogue and coordination among multiple scales of government, water users and scientific knowledge through information exchanges across disciplinary, organisational and knowledge boundaries (Jacobs et al. 2016). These frameworks rely on scientifically credible and socially robust knowledge-action systems to exchange information and guide interactions among participants (Robinson et al. 2011).

WRMs have been a core part of regional water resource decision-making and management for many decades (Brown et al. 2015; Jacobs et al. 2016) but developers of WRMs and users of the knowledge they provide have struggled to articulate their value within wider socio-political contexts. Growing pressures on water availability, combined with shifting governance and management, has resulted in a need to re-engage with design and application of WRM (van Asselt and Rotmans 2002) to incorporate diverse contributions from multiple stakeholders, communities and interest groups (Kroon et al. 2009). Knowledge gaps across large basins are common and pose challenges to perform system-wide analyses, communicate findings and justify regional responses to phenomena such as droughts and climate change.

The growing need for resource managers to learn, experiment and adapt to complex threats and opportunities that are inherent in water decision-making has attracted the attention of a growing field of sustainability science (Clark and Dickson 2003). This field of research draws on the notion of boundary work (Gieryn 1983) that describes efforts of two-way, iterative communication between actors across the science/decision-making boundary to translate and mediate knowledge into policy decisions. For boundary work to be useful and usable, it needs to not only be scientifically credible but also salient for real-world applications and reflect legitimate information-gathering processes that consider a range of values, interest and concerns (Cash et al. 2003; Clark et al. 2016; Jacobs et al. 2016). In this article, our focus is on how federal governance structures utilise WRMs as ‘boundary objects’ to enable the sharing of knowledge across multiple state and national governments, stakeholder interests and disciplinary perspectives to support river basin planning.

This paper draws on responses from WRM designers and users in two fully allocated, drought-prone and contested transboundary river basins: the Colorado River Basin (CRB) in North America and the Murray-Darling Basin (MDB) in southeastern Australia. Both basins are characterized by federal water governance structures and WRMs were recently developed or enhanced in both basins amidst significant water planning and management reforms in response to severe droughts. The article begins by reviewing IWRM as it relates to the development and application of WRMs to enable water managers to link knowledge with actions required to address complex water resource management issues, then draws on the sustainability science literature to describe the key perspectives and attributes of boundary work. Regional water resource planning contexts within the basins are then reviewed and the survey responses analysed.

Theoretical framework

Much has been written on water governance and the concept of IWRM, including what should be integrated to achieve an inclusive yet practical management framework (Biswas 2004; Gourbesville 2008; GWP 2000). The co-evolution of water institutions—the rules, norms, values and shared knowledge of practitioners—alongside development of governmental authorities and the power instilled in them, creates challenges that can make water decision-making regimes resistant to change (Pahl-Wostl 2009). One challenge includes the integration of basin-scale technological approaches with increasing contributions from diverse knowledge sources and interests (Raymond et al. 2010). How such knowledge can be incorporated into reductionist, yet often relied upon, decision-making frameworks is not a trivial task. This requires balancing the rationale and urgency of the decisions to be made with the availability of useful information to inform these decisions.

The term ‘boundary work’ has been coined to describe and analyse the continuous transfer and integration of knowledge across functional and organisational boundaries and different knowledge domains (Jasanoff 2004; Lemos and Morehouse 2005). Models can serve as key boundary objects to translate complex scientific knowledge into decision-making provided these models are supported by appropriate institutional rules and practices (cf. Rayner et al. 2005; White et al. 2010). ‘Boundary organisations’—such as government and non-government water management organisations—also perform boundary work by acting as knowledge sharing and translation intermediaries between different stakeholders (Buizer et al. 2016; Clark et al. 2016), which become particularly relevant when knowledge and power imbalances exist (Zeitoun and Warner 2006).

In the context of this paper, a key role for boundary organisations is to build and apply WRMs that are trusted by stakeholders and to ensure that interests and individuals are respected, valued and engaged in a legitimate process (Lemos and Morehouse 2005). However, the process by which trust in WRMs is gained among competing actors is poorly understood beyond notions of stakeholder participation (Olsson and Andersson 2007; Van den Belt 2004). This is particularly relevant in federal river systems that are bound by a common overarching government, but ownership and management of water is maintained at subnational levels. As a result, local and state governments must find ways to co-manage the shared resource. In doing so, WRMs become important ‘boundary objects’ for organisations to develop and communicate collective knowledge through assimilation of information across multiple sources, time scales, spatial domains and jurisdictions (Liu et al. 2008).

Multi-level and polycentric governance structures (Ostrom 2010) have been shown to increase resilience to environmental shocks and system-wide changes through adaptation (Pahl-Wostl 2009); however, coordination among multiple governance institutions is important to avoid fragmented decentralization (Pahl-Wostl et al. 2012). The collective use of WRMs provides a tangible form of coordination across multiple state actors or between states and an overarching federal or basin-wide government. The application of WRMs for dispute resolution in a multi-jurisdictional river basins is well established (Dinar et al. 2007), and many river basins rely on them for effective management among competing interests. How WRMs are developed, managed, shared and applied to build consensus among competing actors has received limited attention and provides a point of departure for this research.

Research context and methods

Water resource model contexts

Colorado River Basin

The CRB drains portions of seven states before flowing across the international border of Mexico and into the Gulf of California. The river is managed and operated through a complex assemblage of regulations, which are collectively referred to as the Law of the River (MacDonnell et al. 1995) that establishes the rules for sharing between states and nations. Within the USA, the Bureau of Reclamation (USBR) is the primary authority charged with the operation of the dams and reservoirs and the management of water deliveries. Water-sharing arrangements between the USA and Mexico are defined in the 1944 Treaty and administered by the joint International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC).

In 2000, the USBR completed an environmental impact statement (EIS) to develop guidelines for the allocation of surplus water among the lower basin states (USBR 2000) and, in doing so, ushered in a new era of collaborative WRM use in the basin. Responding to a rapid decline in reservoir storage, growing demands and climate change risks, a Shortage Criteria EIS (USBR 2007) was produced soon thereafter to explore potential definitions and responses to shortage conditions among the lower basin states and provide recommendations to improve coordination of reservoirs. These studies led to the official Records of Decision (ROD) signed by both the USBR and the Secretary of the Interior (DOI 2001; DOI 2007), which became part of the Law of the River.

Central to each of these efforts was a WRM known as the Colorado River Simulation System (CRSS) (Garrick et al. 2008; Jerla et al. 2011). Originally designed by the USBR as a FORTRAN model (Cowan et al. 1981), the CRSS model was transferred to the RiverWare platform in 1990s with an objective of making the model more adaptable to changing policies and accessible to a wider audience of stakeholders (Zagona et al. 2001). With this development, expertise in the CRSS model began to extend beyond the USBR. New users included state governments, municipalities and water authorities (USBR 2012). Understanding the role of the CRSS in the policy formulation process, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and certain Native American tribes, who hold substantial interests or water rights in the basin, also sought to build their own expertise through collaboration with universities and externally hired consultants (Westfall and Bliesner 2006; Wheeler et al. 2007).

The USBR made the CRSS model freely available to a Stakeholder Modelling Workgroup comprised of technical representatives from the different organisations and held regular meetings with interested technical and non-technical parties. This allowed the USBR to share outputs from the model and receive well-informed suggestions for improvements. These efforts were not only to promote understanding of the scenarios developed, but also to encourage stakeholders to evaluate and propose management alternatives that could meet their own objectives. As more stakeholders became familiar with the model, the tool evolved into a platform for exploring, sharing and testing alternative ideas for river management. Technical experts could evaluate proposals presented at a formal policy level and also communicate and scrutinize ideas informally across networks of modellers.

On an international level, the Mexican government recognised the increasing need to engage over future river management decisions and held a RiverWare training session in April 2008 to increase their modelling capacity. Formal bilateral negotiations began in 2011 that used the CRSS as the central analytical platform and included participation of federal and state governments, municipalities, NGOs and agricultural districts. Minute 319 to the 1944 Treaty was signed in November 2012 that demonstrated a new level of multi-level coordination (Buono and Eckstein 2014).

Murray-Darling Basin

The National Water Initiative is the blueprint for Australian water policy and planning reform and its policy prescriptions and objectives are widely accepted as salient and appropriate for Australia (COAG 2004). Local, state and basin water planning institutions have agreed on a set of key elements within their water planning frameworks such as stakeholder engagement and applying a risk-based approach to water resource management. Its implementation is the responsibility of state jurisdictions or regional multi-state partnerships such as those within the MDB.

WRMs such as IQQM (Simons et al. 1996), REALM (Perera et al. 2005) and MSM-BIGMOD (Close et al. 2004) have been used as decision support tools to understand, plan and manage MDB water resources over the past four decades, but principally developed at the individual sub-basin level and managed by state agencies. Disparate characteristics, such as temporal resolutions and alternative depictions of water rights systems, exist between the various sub-basin models (MDBA 2012). In the throes of an exceptional decade-long drought, the Australian government passed the 2007 Water Act, which directed the formation of the Murray-Darling Basin Authority (MDBA) and its mandate to strategically plan and manage the basin as a whole. From this greater centralized management paradigm, the need to standardize and merge the existing modelling frameworks emerged. There were significant challenges to link the individual historical models within an integrated river system modelling framework (MDBA 2012). With funding from the federal government, the new Source modelling platform was developed by eWater Cooperative Research Centre (CRC) partners that included the national science organisation CSIRO. Source is now managed by eWater LLC, with a goal to eventually replicate and replace the individual sub-basin models and to provide a common analytical framework (Dutta et al. 2013; Welsh et al. 2013). While the existing models continued to be used during this period of critical drought, the new platform was designed with the intention that multiple state agencies would adopt it for their future planning purposes. The process of adoption of this common platform continues today.

The models strive to simulate the management of water across four states according to parliamentary agreements. Under these regulations, the downstream state of South Australia receives a minimum annual entitlement flow and the balance is shared according to requirements for salinity mitigation, flood storage and environmental flows as well as water user entitlements (Connell and Grafton 2011; MacDonald and Young 2001; Walker et al. 2003).

The 2007 Water Act recognised the risk of environmental degradation resulting from low flows caused by over-abstraction coupled with the persistent drought. An ambitious agenda of water policy reform is set to establish sustainable diversion limits (SDL), resulting in more than 20% of previous extracted water use recovered for the basin’s freshwater and estuarine ecosystems (Bark et al. 2014). This has required the application of integrated water governance frameworks that can be used to negotiate various uses to sustain multiple values and encourage local community input and review of management objectives and priorities (Robinson et al. 2015). A challenge implicit in the resulting Basin Plan 2012 is establishing an approach that provides credible water resource-sharing decisions between all water users, including the environment, managing the basin as a single system while being responsive to local values and priorities. In this research, we contend that the process of model development, adaptation and application to meet these multiple needs constitutes an example of boundary work.

Methods

Information was collected through multiple routes including reviews of government-produced reports and academic literature and from a semi-structured survey. A stratified sample selection was followed augmented with snowballing. In the period January 2016 through February 2017, invitations were sent to the national- and state-level WRM developers and users, as well as individuals representing stakeholder interest groups. The responses collectively represent a variety of backgrounds, interests and perspectives from both sides of the science-policy interface and multiple institutional positions in each the basin. Many perspectives were sought; however, inevitably, many could not be reached through this research. Only those who know of models or their usage could be queried, so this inevitably excludes many parties affected by their outcomes. The semi-structured survey asked respondents about their perspectives of WRM design and application. Questions explored the use of models (science information) in decision-making. Survey data was then analysed using the Cash et al. (2003) framework that focuses on how to create and use knowledge systems for sustainable development. In this context, the focus was on the need for WRM information to be credible (scientific adequacy), legitimate (its development is respectful of divergent stakeholder beliefs and values, fair and unbiased) and salient (information is available and relevant for decision-making).

In total, 44 invitations were sent and 17 returned for a 39% response rate. Ten completed questionnaires were returned from the CRB including four from federal level governments in the USA (USBR and IBWC-USA), two from federal-level governments in Mexico (CONAGUA and IBWC-Mexico), two from NGOs and two from state-level water authorities. In the MDB, we received seven completed questionnaires including three from federal level researchers (CSIRO), two from the basin authority (MDBA), one from a state government (South Australia) and one from a state-level irrigation district.

We coded the questionnaire responses for themes (Bernard and Ryan 2010) using a constructivist grounded theory approach that allowed strong themes to emerge (Glaser and Strauss 1967). These responses were then triangulated with the narratives provided in reports and other available literature, noting the authors’ role and nature of their perspectives. As survey responses indicated that WRMs were acting as boundary objects, we explored if and how respondents discussed the primary functions of boundary organisations—convening, translation, collaboration and mediation (Cash et al. 2006). Throughout the results and subsequent discussion, we provide respondent-approved quotes to illustrate key findings.

Results

Survey results are organised by credibility, legitimacy and saliency attributes of effective evidence-based decision-making (Cash et al. 2003) with attention to both the physical ‘hardware’ (WRM infrastructure and resource commitments) and the institutional ‘software’ (governmental roles and shared knowledge capacities within each basin) that acted to enable or prevent the effective use of WRMs to guide water resource management decisions.

Credibility

The CRSS was widely considered scientifically credible by all respondents across the CRB, but not without critiques. Survey respondents noted the modelling software platform, hydrologic data and methods used to evaluate uncertainty are well supported by peer-reviewed literature, and equations simulating water management are structured as hierarchical rules that can be readily mapped onto the Law of the River. Throughout the basin, water demands were provided by the individual states based on population projections. However, assumptions of exaggerated future demands from the upper basin states to safeguard future allocations challenged the credibility of WRM projections. To manage this critique, the USBR documented model assumptions thoroughly during the production of each EIS so that decisions could be accountable to the collaborative decision-making process. Maintaining a cooperative working environment with the upper basin states required accepting these aspirational demands.

In the MDB, the tools used to prepare the Basin Plan 2012 can be distinguished from the subsequent platform and model developments. The historical sub-basin models—IQQM, REALM and MSM-BIGMOD—were generally perceived to be scientifically credible due to the regard held for the model developers and the established institutional usage of these models. The scientific credibility of the new Source software and the models actively being developed in this framework was supported by detailed documentation describing guidelines for model development (Black et al. 2014), quality control measures and procedures (MDBA 2012) and the scrutiny during the development of its internal algorithms (Welsh and Black 2010). The development of new models using this platform has however attracted some criticism among various non-federal stakeholders. One respondent stated they ‘have often been frustrated by the lack of evidence to support the modelling of the Murray-Darling Basin Authority’. Perceptions of credibility were influenced by limited access to the models, which are generally owned by individual states, but the credibility of the scientific methods themselves were not directly questioned by respondents.

Legitimacy

According to respondents, the legitimacy of the CRSS was largely attributed to the direct access to the model given to stakeholders and the transparency that the platform provides. The USBR-developed model is freely available to participants through the Stakeholder Modelling Workgroup; however, users must purchase a RiverWare software licence to be able to modify the model or hire external consultants to do so. Survey respondents commented that the ability for stakeholders to analyse, operate, challenge and modify the CRSS helped them gain a sense of ownership during the interstate negotiations that resulted in the EISs and allowed them to formulate new alternatives to be considered. Perceptions of model legitimacy among various non-modelling stakeholders such as some Native American tribes were not included in this assessment. These groups often rely on the USBR to interpret the information that the CRSS produces.

Within the MDB, the legitimacy of historical WRMs was initially established through their relative simplicity at the time of initial development, followed by the continuous use and enhancement across state offices. As new models were developed using the Source platform, expert input and algorithms from the legacy models have been incorporated; thus, the developers are hopeful their legitimacy would transfer as well. While this is logical from an engineering perspective, cautions to conform to a basin-wide norm could be seen. State governments are generally responsible for developing their own local Source models while managing and stakeholder engagement with respect to WRMs and their outputs. Although the move to the new platform was generally seen as positive, some state’s constituents expressed hesitations. One respondent noted that their opportunity to provide feedback was limited to the results of the models and not the models themselves. Another respondent questioned the accessibility of the model when claiming the ‘custom approach, along with limited documentation, makes use of the models other than (by) the MDBA very difficult’. The prolonged adoption of the platform and implementation of new models reflects a degree of caution among the states or the constituents they represent. Problems of institutional fragmentation and historical model developments have challenged coordination and boundary work efforts between government and civil society, among state governments and between states and the MDBA.

The perception of legitimacy of the WRMs in both basins is presumably affected by the degree of inclusion in the modelling process. Sufficient knowledge of WRMs, the removal of barriers which inhibit their usage, and a willingness to share and learn from them are prerequisites to fully realize and leverage their potential value.

Saliency

In order to fulfil their respective mandates to manage water resources sustainably into the future, the USBR and MDBA are the primary drivers of new model development. One challenge facing both basins was the evolution of water management concerns that required the function and scope of their WRMs to expand. In the case of the CRB, the saliency of the CRSS model remained strong among federal and state governments; however, NGOs found the narrowness of the design to be a significant limitation when modelling environmental objectives. As one respondent noted, ‘The fact that environmental flows are not assessed likely makes it easier for water managers to make decisions, as you are less likely to be concerned if you aren’t getting information that says you should be concerned’. This can raise significant information equity issues. As one respondent observed, ‘Stakeholders could be disadvantaged because the model is not geared/suited towards their needs’. This suggests the need for active management to avoid the inadequacy of models inadvertently or intentionally foreclosing affected interests.

While inclusion or exclusion of particular aspects in a WRM is subject to debate, respondents agreed that complex management decisions are difficult if not impossible to make without a basin-wide model. Concurrently, many respondents recognised that models are generally not able to provide single best solutions to resolve water management conflicts. This ‘necessary but insufficient’ role of WRMs was exemplified during the negotiations to develop the EISs when solutions proposed by one state or coalition would undergo a technical review by other parties using the CRSS. These reviews would occur alongside evaluations from legal and strategic policy-oriented perspectives before acceptance or counterproposals could be offered. This process would iterate until mutually agreeable outcomes could be reached. Throughout the development of Minute 319, similar iterations of proposed solutions followed by legal, political and technical analyses occurred between the two nations.

As the experience of WRM development and application in the MDB highlights, issues such as severe drought can put enormous pressure on models to deliver immediate results to support the development of new water management guidelines. WRMs developed using historical conditions must be adapted to reflect unforeseen extremes resulting from non-stationarity (Milly et al. 2008). The need for integrated models to provide highly relevant decision support for basin-wide policies became increasingly clear. While many respondents highlighted that model saliency became a focus in terms of their capabilities, strengths and limitations, another respondent astutely noted that ‘A lot of energy can be expended in arguing about the model rather than what its saying’.

The responses also provided evidence that the WRMs were performing the functions of boundary management: convening, translation, collaboration and mediation (Cash et al. 2006) and therefore we organise other key insights by these functions.

Convening

An important initial function of boundary work is convening affected parties, but this task can face numerous logistical challenges such as the availability of sufficient funding to enable stakeholder input, or context-specific challenges such as the selection of participants (Glicken 2000). This latter is delicate as excluding certain participants can delegitimize any boundary work before it begins, while including too many voices can render a discussion ineffective. Convening stakeholders in a federal context poses unique challenges of representation. The degree to which interests are adequately represented by subnational governments depends on the democratic nature and political focus of the government. As an example, non-economic interests may not be on the agenda of governments in certain regions, and the inclusion of NGOs may be necessary to voice these concerns. Establishing clear objectives at the outset can assist with deciding the composition of a group (Liu et al. 2008), but can also prematurely influence the outcome through inclusion or exclusion of interrelated topics. This comparative analysis highlights that the capacity of water management institutions to work with WRMs and for stakeholders to engage in WRM information is key to the function of convening.

Development of the CRSS for managing the CRB began in 1970s by the USBR and from 1973 to 1978, it was ‘given serious scrutiny and many changes were made to solve some of the problems and strengthen some of areas of weakness that had been detected’ (Cowan et al. 1981: p. 11). Participation from the states likely began then, but one respondent to our questionnaire surmised that the ‘entities least satisfied [today] with Colorado River Management were not at the table: tribes, conservation organizations, Mexico’. While the lack of inclusion of these stakeholders certainly simplified its initial development, agreements over future shared management would eventually require integration of these affected parties into the modelling process.

During the interstate negotiations leading to the development of recent guidelines and agreements, the states increased their in-house modelling capacity and began to operate the CRSS independently of the USBR. Shortly thereafter, NGOs also invested in their own modelling expertise, which allowed greater access to, and understanding of, the alternatives under consideration. Within the USA, the USBR facilitates a Stakeholder Modelling Workgroup that includes any stakeholder that ‘actively runs the model or uses its results’, which continues to be a key forum to share model assumptions, structure and outputs. Through this technical working group, relationships that were developed throughout the negotiations are maintained and continue to be a cornerstone of the acceptance of the CRSS. Upon commencement of the binational negotiations that resulted in Minute 319, the USBR also allowed the Mexican government to access the CRSS. This allowed Mexico to ask informed questions regarding how the USA administered their treaty allocation and better understand management process of the Colorado River. Throughout the binational negotiations, interstate and international committees of technical stakeholder representatives convened regularly to explore mechanisms of cooperation.

In the MDB, the need to meet the obligations under the Water Act 2007 and to determine the SDLs became a major impetus to develop a nationally consistent approach to modelling for water management and planning. Significant efforts were made to engage and inform stakeholders throughout the development of the Basin Plan (MDBA 2009). State water agencies provided the models used to develop the integrated modelling framework and offered comments throughout the process, but convening of technical individuals across the states during the integrated WRM development and application was less apparent than in the CRB (MDBA 2010a; MDBA 2010b; MDBA 2012). Since the development of the new Source modelling platform began, significant efforts have been made to convene stakeholders. Early workshops were held across the basin to elicit user requirements from eWater CRC partners. A team of senior project staff travelled across Australia to hold meetings with key management organisations in all states and territories with the aim of gaining their engagement (Welsh and Black 2010). In addition, a technical user group (TUG) was convened that included individuals from the eWater CRC partner organisations that were actively involved in software development.

Translation

The translation of information and knowledge across language or cultural differences is a primary function of boundary organisations and can manifest with effective boundary objects developed or applied by those institutions. This can be either through translators, a common spoken language, or in the case of certain endeavours, the nature of the boundary work itself (Robinson et al. 2014). Models can be the medium for effective communication, even when language or other cultural differences exist, but can also present a barrier to some stakeholder’s understanding given uncertainty inherent in such decision support tools (Weichselgartner and Kasperson 2010).

The benefits of developing strategies to facilitate structured knowledge translation between multiple actors and water governance organisations were highlighted as key ingredients to the effective use of WRMs. In the case of the CRB, one respondent noted the importance of WRMs to not be a ‘black box’ and many emphasised the advantages of its transparent structure. The USBR believed that ‘transparency facilitated stakeholders being on relatively equal ground, rather than [certain parties] having an advantage’ and one non-governmental stakeholder recognised that a model could create ‘a common language’ to enable participants from different levels of decision-making to engage in the complex task of policy development. The IBWC emphasised the translational function of the model by stating, ‘with the aid of the modelling information, the stakeholders were able to visualize the effects of drought and expected water allocations to users in both countries’.

Translation across disciplines is an inherent challenge when using expert systems like WRMs. Experience from both basins demonstrate that participants must have sufficient technical expertise to engage in a model-based dialogue. This often requires substantial investments in time and resources for capacity building, resulting in a ‘limited community of skilled modellers’ according to one respondent. Stakeholders unable to build or hire needed capacity can be quickly disadvantaged due to a lack of understanding of the logic and limitations of models, the rationale behind the assumptions imbedded within them and the value they provide to the decision-making process. The inability to communicate these aspects can cause a general scepticism of models, exacerbated in the midst of a critical situation such as a severe drought. Those with the required capacity perceived limitations when ‘Resources were required to explain modelling results to decision makers (and also explain what models could and couldn’t do)’, particularly when complex results are presented with jargon and statistics that users of the information cannot relate to. Communicating hydrologic uncertainty, particularly in face of unprecedented conditions, was a critical factor in the MDB.

Collaboration

The process of building consensus towards a particular objective inherently requires collaboration (Margerum and Robinson 2015).The development of a shared fact basis and the co-production of knowledge to underpin water models (Jasanoff 2004) or the process of overcoming adversity (Susskind and Cruikshank 1987) are examples of powerful forces that can bond parties together as boundary-spanning exercise. Such actions require time and effort to achieve success and can be difficult in water management contexts where there are multiple decision-makers, users and values to consider (Islam and Susskind 2012; Linnerooth-Bayer et al. 2001; Robinson et al. 2014). The benefits of collaborative model development for facilitating a broader understanding of trade-offs among stakeholders has been emphasised (van de Belt 2004); however, such collaboration can be hindered by time pressure for an outcome, the specialization of knowledge required, or fear of political debates subverting the process or results (Gilfedder et al. 2016).

Collaborative decision-making within a federal river context is the main justification for the formation of a river management organisation or interstate compacts. A common WRM platform for analysis provides a medium for this collaboration. Agreements reached among individual states are expected be accepted by the federal government, thus minimizing federal interference or regulations being imposed. The ability to reach such a consensus is facilitated by parties having equal access to the analytical tools and decision-making process and presumably some capacity to influence them. An iterative exchange of possible solutions during negotiations is accelerated considerably if each party has trust in a common tool to develop and analyse new ideas, thus avoiding the risk of multiple models providing conflicting results.

In the case of the CRB, ‘official’ modelling is conducted by the USBR, with regular input and review from the states and other stakeholders in the Stakeholder Modelling Workgroup. When the CRSS was transferred to the RiverWare software platform, the goal was largely to encourage more collaborative participation; however, most respondents indicated that it still requires a high level of expertise to understand, operate and modify. Many emphasised the need for a significant amount of time to understand and become comfortable with the model. One respondent stated, ‘Building trust in the model, model framework and assumptions, takes much longer than the actual time to run the model and produce the results’. Given Mexico’s initial inexperience with the CRSS during Minute 319 negotiations, one Mexican modeller identified a challenge as the ‘Lack of available resources for problem solving [and] model building and operation apart from model developer [sic]’. This was reinforced by responses from the USA acknowledging, ‘The U.S. agencies had greater knowledge than their Mexican counterparts in terms of experience’, yet ‘The U.S. worked with Mexico to insure adequate training and knowledge transfer’. While respondents from both sides of border expressed they ‘worked as a team’ with ‘subgroups of modellers and decision makers [that] we always worked together’, others believed that Mexico was reluctant to ‘buy into CRSS analysis’.

The success of collaboration is not necessarily measured by the outcome, but by the process itself. The development of the surplus guidelines helped build interstate cooperation and model acceptance that was leveraged for the subsequent and more contentions shortage EIS. Similarly, the modelling work during Minute 319 was perceived to form a basis for future collaboration between the USA and Mexico. Process benefits were also realized by the NGO’s ability demonstrate a relatively minor impact on other basin users of water dedicated to environmental objectives (Wheeler et al. 2007).

In the MDB, states contributed their individual sub-basin models to form the integrated river system modelling framework used to develop the Basin Plan 2012 (MDBA 2012). The modelling itself was conducted by the MDBA and CSIRO, and comments were provided by the states. Our survey replies and media reports (Kotsios 2017) indicated that various stakeholders continue to hold a deep frustration over a lack of access to the models. Whether development and application of the MDB WRMs for the Basin Plan could have been more transparent or inclusive is still a subject of debate and speculation.

The technical challenges faced in assembling the disparate models for development the Basin Plan have both demonstrated the need for a unified platform and encouraged members of the eWater CRC to work cooperatively to produce the new analytical tools. The new development of the Source modelling platform benefits from modern approaches to facilitate understanding and cooperation such as object-oriented programming, graphical user interfaces, databases and internet communication. Welsh and Black (2010) describe extensive efforts to involve stakeholders during development including solicitation of user requirements, incorporating feedback, holding monthly project update meetings and conducting regular planning meetings. To satisfy the needs of all eWater CRC partners, frequent debates occurred on the appropriate modelling approaches to incorporate. Managing equity in stakeholder influence was often necessary, and when conflicts could not be resolved, multiple methods were incorporated into the software, often prolonging its development.

Mediation

In the original framing of the concept of boundary work, the function of mediation describes the process of reaching consensus across multiple and often competing interests. In the context of a transboundary river, we consider mediation between upstream and downstream jurisdictions, between national and subnational governments, and between governments and a potential plethora of water users. With a sound design to incorporate and adapt to different types of knowledge, interests and geographical domains, WRMs can facilitate this effort as long as parties establish what knowledge the tool can and cannot support or provide.

With the broad understanding that conflicts over water resources are likely to intensify in both basins, increasing stakeholder engagement in WRM design and application will be useful for mediating those conflicts. One respondent in the CRB noted WRMs provide value to negotiations by stating ‘Without models, there would be more speculation about future conditions, and likely more conflict as modelling has helped form the foundations of many important water management decisions’. An NGO stakeholder believed models add value because ‘decisions are complex and intertwined even at small scales and are difficult to evaluate in any other way at large scales’. This statement supports a USBR belief that, by including various stakeholders in the modelling process, it would ‘improve capacity so as to improve understanding regarding negotiations’. The process by which a model becomes a trusted mediation tool relies on its acceptance by conflicting parties. When describing lessons learned in the negotiations, one respondent in the CRB stated “Agreeing to use a particular model in a negotiation setting requires parties’ ‘buy-in’ of the model”. and ‘Model competition and too many models impedes investment in any one’. Even more fundamental was the belief that ‘sound technical data is the foundation of effective/informed negotiation and decision making’ and a key component is to ‘remove … obstacles by sharing data and working off the same dataset’. This aligns with the notion that acceptance of a models requires the ability to explore and challenge them (Olsson and Andersson 2007).

In the MDB, this process continues, but even so, most respondents recognised that model outputs are very influential and heavily relied on to reach agreements. With respect to their role as a mediation tool between states during the development of the Basin Plan, one respondent stated that advantages were held by ‘Upstream states … because they own and develop models of the tributaries’ which they only share with the MDBA not the other states. Issues regarding model ownership were also problematic between the states and the MDBA since the MBDA was only allowed to use the state models under restrictive licences. The assemblage of models were linked together to form an integrated assessment tool that was sufficient to develop the Basin Plan in response to the immediate need; however, it was not distributed among stakeholders and thus limited its ability to serve the function of a common mediation tool. However, after initial proposals, states provided comments and a number of model developments occurred to help refine the SDLs (MDBA 2012).

Discussion

Managers of rivers that flow across federal or international borders are often required to reach agreements on how water is allocated, invoking knowledge-action systems that also cross political—as well as conceptual—boundaries to seek consensus among stakeholders. WRMs are dynamic tools that are used as platforms for making or justifying such decisions, with vastly different institutional approaches and process designs within a multi-actor environment. Although establishing credibility, saliency and legitimacy may not be an explicit objective during initial development, demonstrating these characteristics becomes critical to explain and justify the influence they may have. Achieving and maintained these qualities over time has led to their evolution. The application of WRMs within the context of federal or international rivers demonstrates a complex form of boundary work, often requiring capacity building and iterative development to reach agreements on the potential solutions they suggest (Sarkki et al. 2015).

The CRSS model in the CRB has evolved over five decades as the principal basin-wide planning tool and is generally considered the most salient model to simulate the complex reservoir management decisions that take place at that scale. Since the modernization of the CRSS into the RiverWare modelling platform in 1993, the capability of the software, the general acceptance of the knowledge incorporated into the model and the number of trained model users around the basin have greatly expanded. This has had a profound effect on the credibility and legitimacy of the model among participating stakeholders. The future saliency of CRSS is being tested as environmental flows are becoming increasingly a focus of concern, yet the WRM is ostensibly a reservoir operations and management model. Whether the CRSS model can be adapted to adequately address concerns that require analyses at finer spatial and temporal scales is an issue that the USBR must continuously consider for the this WRM to maintain its legitimacy with regard to these growing concerns.

In contrast, the basin-wide modelling platform in the MDB is earlier in its evolution and has adopted an arguably more challenging task. Although various WRMs have been used across the MDB for over four decades, the Water Act of 2007 and the subsequent CSIRO Sustainable Yields Project (CSIRO 2008) provided the impetus to link the 24 local sub-basin models into an integrated river system modelling framework (MDBA 2012). The advanced state of these sub-basin models and the need to maintain their functionality when replicating them in the newly developed Source software has presented a formidable challenge. The need to include aspects such as various forms of rainfall-runoff modelling to consider climate effects, the multiple accounting procedures used in different states to simulate water trading and recently established environmental criteria aims to establish the saliency of the basin-wide model early in its development. The complexity of this scope has challenged the model development process, yet the MDBA seeks to broaden its user acceptance thus enhancing its future legitimacy.

When analysing the development and application of WRMs within complex river basins with respect to boundary work, it becomes clear that the classical definition of boundary work on the science-policy interface must be expanded to be applicable. Clark et al. (2016) provides a useful generalized framework that classifies a matrix of one to many sources of knowledge mapped onto the various uses of enlightenment, decision-making and negotiation. Within this framework, both the CRB and MDB are examples of political bargaining due to the incorporation of knowledge from multiple experts and the negotiation among multiple users of knowledge. For a tool such as a model to be useful, it must not only be trusted by the scientists that contribute data and design the algorithms, but also by the policymakers that may use its outputs and ultimately the stakeholders that must adhere to the decisions they make from it. Stakeholders can help formulate the model assumptions, but there must be a fundamental match between model functionality and what the users can expect. Both case studies described this critical point of managing expectations and this constitutes a significant component of boundary work.

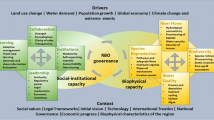

In the case of a complex system such as a transboundary river basin, the various sources of scientific knowledge and decision-makers that require this knowledge are distributed across political and social boundaries. As a result, boundaries exist between the various sources of science, the governance structures involved and the stakeholders affected. Figure 1 presents a conceptual model of these three broad categories of actors, across multiple political boundaries (states) within a federal state, and WRM types. The role of boundary work between each interface is shown with each group’s emphasis of legitimacy, credibility and saliency (Cash et al. 2003). Within this space, we can identify types of models used and their particular emphases. For example, purely scientific fact-finding models may focus on being a credible beacon of truth, yet at the expense of transparency to stakeholders or utility to policymakers. A decision support system may be constructed to be policy-relevant, but lack scientific rigor or limit stakeholder access and understanding. A model focused on stakeholder learning might generate broad understanding of the issues, but lack scientific rigor or the flexibility needed to simulate complex laws, treaties or policies.

The evolution of WRMs emerged as a key theme in this research and is depicted in Fig. 1. Models were initially developed in both basins, as well as many others in the world, as largely scientific endeavours that sought to be useful decision-making tools (1, 2), but largely inaccessible by others who may wish to challenge their assumptions. As the value of stakeholder participation and decentralized governance emerged, the need for greater access to these influential tools grew (3). The migration of the CRSS into the RiverWare software starting in 1993 and the development of the Source in 2007 were both substantial efforts to increase stakeholder participation and hence find the right balance between legitimacy, credibility and saliency (towards 4). In the context of river basin management, this has been termed a hydro-policy model (Wheeler et al. 2016).

For a model to serve as an effective boundary object between multiple stakeholders, policymakers and scientific sources, the issue of access emerged as critical factor. Limitations to model access can be a result of many reasons that include, but are not limited to, proper training and understanding, financial resources to invest in the knowledge required to participate, institutional barriers such as intellectual property rights, or concerns regarding the of loss of local control over resources. On one hand, a lack of willingness or ability on the part of stakeholders to engage with a WRM can limit their influence in a negotiation hence leading to inequitable outcomes, while on the other hand, a process that excludes willing and able participants delegitimizes a collective modelling effort. Furthermore, the use of competing or inaccessible models can devolve a difference in perspective to a battle of experts, which misses the opportunity to find collective solutions. Each of these barriers have been, and must be, addressed by developers, managers and users of WRMs if they are to serve as effective boundary objects. In the MDB, one respondent claimed, ‘The models are very complicated and require an intimate knowledge of the model and the system to be able to run and modify the model’. In the CRB, NGOs hired external consultants to support their needs but explained, ‘There’s usually more useful modelling that could be done than we can afford’. In both basins, there is reluctance by the developers to share models widely outside of technical groups ‘either for security reasons or fear that others will not have the relevant skills to run the model appropriately’. Expanding research to include communities and landowners affected by the outcomes of models but lack access to them for various reasons is an important direction for future work. Although clearly not the arbitrators of truth, WRMs have a significant influence over discourse of water management and the misuse of models can complicate negotiations or compromise their function as effective tools for mediation. Developing effective protocols for access and peer review can help to resolve these challenging issues.

Conclusions

Water resource models (WRMs) of federal and international rivers have emerged as potent examples of boundary objects serving the functions of boundary work to handle the complexities of allocating natural resources in regions experiencing environmental changes. This becomes increasingly critical, as the potential for future conflict exists at multiple levels and between multiple users and uses. Both case studies illustrate how drought and future drought risk initiated, and has sustained, significant advancements of WRMs to manage boundary work. WRMs are influential tools for supporting the decision-making process and can provide insight into system-wide dynamics; however, they are simplifications of reality, imperfect by nature, and by understanding this, consideration of other sources of knowledge is concurrently needed.

WRMs have evolved through the years to become more scientifically accurate and accessible to a wider audience through improved user interfaces; however, they are still largely tools that require a significant amount of technical expertise to wield. As with any influential tool—physical, legal, etc.—inequities in power can emerge between parties with differing institutional capacity or knowledge to use them properly. If WRMs are to be used in a negotiation context, recognising and managing this inequity through measures such as capacity building and adequate representation is critical to achieve an equitable outcome.

While a process or tool developed in one river basin may not be directly applicable to another basin without a thorough understanding of similarities and differences among them, many lessons drawn from this research are potentially transferable to other contested federal or transboundary contexts in which WRMs are implemented such as the Nile River, the Mekong River and the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. Similar to other knowledge information systems seeking to provide viable and sustainable solutions, the challenges for WRMs often lies in the tensions between saliency, credibility and legitimacy. Therefore, we provide three key recommendations:

-

1.

A well-structured modelling process should identify and rationalize what aspects are included and excluded in the framework, resulting in explicit knowledge gaps that stakeholders could help to fill.

-

2.

Stakeholder groups can potentially benefit significantly from investing in their own technical capacity to understand, review and use models collaboratively or independent of the model developers.

-

3.

Model developers must allow WRMs to be available for scrutiny by knowledgeable stakeholders to enhance model acceptance and relevance and to potentially provide training opportunities that builds stakeholder capacity and increases model credibility through active participation.

References

Bark R, Kirby M, Connor JD, Crossman ND (2014) Water allocation reform to meet environmental uses while sustaining irrigation: a case study of the Murray–Darling Basin, Australia. Water Policy 16:739–754. https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2014.128

Bernard HR, Ryan GW (2010) Analyzing qualitative data: systematic approaches. SAGE, London

Biswas AK (2004) Integrated water resources management: a reassessment. Water Int 29:248–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060408691775

Black DC, Wallbrink PJ, Jordan PW (2014) Towards best practice implementation and application of models for analysis of water resources management scenarios. Environ Model Softw 52:136–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2013.10.023

Brown CM, Lund JR, Cai X, Reed PM, Zagona EA, Ostfeld A, Hall J, Characklis GW, Yu W, Brekke L (2015) The future of water resources systems analysis: toward a scientific framework for sustainable water management. Water Resour Res 51:6110–6124. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015WR017114

Buizer J, Jacobs K, Cash D (2016) Making short-term climate forecasts useful: linking science and action. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113:4597–4602. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0900518107

Buono RM, Eckstein G (2014) Minute 319: a cooperative approach to Mexico–US hydro-relations on the Colorado River. Water Int 39:263–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2014.906879

Cash DW, Borck JC, Patt AG (2006) Countering the loading-dock approach to linking science and decision making: comparative analysis of EI Nino/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) forecasting systems science. Technology & Human Values 31:465–494. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243906287547

Cash DW, Clark WC, Alcock F, Dickson NM, Eckley N, Guston DH, Jäger J, Mitchell RB (2003) Knowledge systems for sustainable development. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100:8086–8091. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1231332100

Clark WC, Dickson NM (2003) Sustainability science: the emerging research program. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100:8059–8061. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1231333100

Clark WC, Tomich TP, van Noordwijk M, Guston D, Catacutan D, Dickson NM, McNie E (2016) Boundary work for sustainable development: natural resource management at the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113:4615–4622 doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0900231108

Close AF, Mamalai O, Sharma P The River Murray flow and salinity models: MSM-BIGMOD. In: Dogramaci S, Waterhouse A (eds) Engineering Salinity Solutions: 1st National Salinity Engineering Conference 2004, Barton, A.C.T, 2004. Engineers Australia, pp 337–342

COAG (2004) Intergovernmental agreement on a national water initiative between the commonwealth of Australia and the governments of New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia, the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory. Council of Australian Governments, Canberra, p 39

Connell D, Grafton RQ (2011) Water reform in the Murray-Darling Basin. Water Resour Res 47:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1029/2010WR009820

Cowan MS, Cheney RW, Addiego JC (1981) Colorado River simulation system: an executive summary. United States Department of the Interior, Denver, p 12

CSIRO (2008) Water availability in the Murray-Darling Basin. A report from CSIRO to the Australian Government from the CSIRO Murray-Darling Basin sustainable yields project, CSIRO, Australia, p 67

Dinar A, Dinar S, McCaffrey S, McKinney D (2007) Bridges over water: understanding transboundary water conflict, negotiation and cooperation vol 3. World Scientific Publishing Co Inc, Singapore

DOI (2001) Record of decision—Colorado River interim surplus guidelines final environmental impact statement. U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington DC, p 29

DOI (2007) Record of decision—Colorado River interim guidelines for lower basin shortages and the coordinated operations for Lake Powell and Lake Mead. U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington DC, p 59

Dutta D, Wilson K, Welsh WD, Nicholls D, Kim S, Cetin L (2013) A new river system modelling tool for sustainable operational management of water resources. J Environ Manag 121:13–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.02.028

Garrick D, Jacobs K, Garfin G (2008) Models, assumptions, and stakeholders: planning for water supply variability in the Colorado River Basin 1. JAWRA J Am Water Resour Assoc 44:381–398. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-1688.2007.00154.x

Garrick DE, Anderson GR, Connell D, Pittock J (eds) (2014) Federal rivers: managing water in multi-layered political systems. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham

Gieryn TF (1983) Boundary-work and the demarcation of science from non-science: strains and interests in professional ideologies of scientists. Am Sociol Rev 48:781–795. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095325

Gilfedder M, Robinson CJ, Grundy M (2016) Where has all the salinity gone? The challenges of using science to inform local collaborative efforts to respond to large-scale environmental change. In: Margerum RD, Robinson CJ (eds) The challenges of collaboration in environmental governance. Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc., Cheltenham, UK, pp 131–151. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781785360411.00015

Glaser BG, Strauss AL (1967) The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Pub, Chicago

Glicken J (2000) Getting stakeholder participation ‘right’: a discussion of participatory processes and possible pitfalls. Environ Sci Pol 3:305–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1462-9011(00)00105-2

Gourbesville P (2008) Integrated river basin management, ICT and DSS: challenges and needs. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C 33:312–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pce.2008.02.007

GWP (2000) Integrated water resources management—TAC background paper no. 4. Global Water Partnership, Stockholm, p 67

Islam S, Susskind L (2012) Water diplomacy: a negotiated approach to managing complex water networks. Routledge, New York

Jacobs K, Lebel L, Buizer J, Addams L, Matson P, McCullough E, Garden P, Saliba G, Finan T (2016) Linking knowledge with action in the pursuit of sustainable water-resources management. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113:4591–4596. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0813125107

Jasanoff S (2004) States of knowledge: the co-production of science and social order. International library of sociology, Routledge, London New York

Jerla C, Morino K, Bark R, Fulp T (2011) The role of research and development in drought adaptation on the Colorado River Basin. In: Grafton RQ, Hussey K (eds) Water resources planning and management. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 423–438

Kotsios N (2017) Murray Darling Basin plan: John Howard’s vision still controversial. The Weekly Times

Kroon FJ, Robinson CJ, Dale AP (2009) Integrating knowledge to inform water quality planning in the Tully–Murray basin, Australia. Mar Freshw Res 60:1183–1188. https://doi.org/10.1071/MF08349

Lemos MC, Morehouse BJ (2005) The co-production of science and policy in integrated climate assessments. Glob Environ Chang 15:57–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2004.09.004

Linnerooth-Bayer J, Löfstedt R, Sjöstedt G (eds) (2001) Transboundary risk management. Risk, society, and policy series. Earthscan Publications Ltd., London

Liu Y, Gupta H, Springer E, Wagener T (2008) Linking science with environmental decision making: experiences from an integrated modeling approach to supporting sustainable water resources management. Environ Model Softw 23:846–858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2007.10.007

MacDonald DH, Young M (2001) A case-study of the Murray-Darling Basin. Policy and Economic Research Unit, CSIRO Land and Water, Adelaide, p 89

MacDonnell LJ, Getches DH, Hugenberg WC (1995) The law of the Colorado River: coping with severe and sustained drought. JAWRA J Am Water Resour Assoc 31:825–836. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-1688.1995.tb03404.x

Margerum RD, Robinson CJ (2015) Collaborative partnerships and the challenges for sustainable water management. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 12:53–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2014.09.003

MDBA (2009) Stakeholder engagement strategy: involving Australia in development of the Murray–Darling Basin plan. Murray-Darling Basin Authority, Canberra, p 9

MDBA (2010a) Guide to the proposed basin plan: an overview. Murray-Darling Basin Authority, Canberra, p 223

MDBA (2010b) Guide to the proposed basin plan: technical background. Murray-Darling Basin Authority, Canberra, p 453

MDBA (2012) Hydrologic modelling to inform the proposed basin plan: methods and results. Murray-Darling Basin Authority, Canberra, p 325

Milly PCD, Betancourt J, Falkenmark M, Hirsch RM, Kundzewicz ZW, Lettenmaier DP, Stouffer RJ (2008) Stationarity is dead: whither water management? Science 319:573–574. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1151915

Olsson JA, Andersson L (2007) Possibilities and problems with the use of models as a communication tool in water resource management. Water Resour Manag 21:97–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-006-9043-1

Ostrom E (2010) Beyond markets and states: polycentric governance of complex economic systems. Transl Corp Rev 2:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/19186444.2010.11658229

Pahl-Wostl C (2009) A conceptual framework for analysing adaptive capacity and multi-level learning processes in resource governance regimes. Glob Environ Chang 19:354–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.06.001

Pahl-Wostl C, Lebel L, Knieper C, Nikitina E (2012) From applying panaceas to mastering complexity: toward adaptive water governance in river basins. Environ Sci Pol 23:24–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.07.014

Perera BJC, James B, Kularathna MDU (2005) Computer software tool REALM for sustainable water allocation and management. J Environ Manag 77:291–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2005.06.014

Raymond CM, Fazey I, Reed MS, Stringer LC, Robinson GM, Evely AC (2010) Integrating local and scientific knowledge for environmental management. J Environ Manag 91:1766–1777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.03.023

Rayner S, Lach D, Ingram H (2005) Weather forecasts are for wimps: why water resource managers do not use climate forecasts. Clim Chang 69:197–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-005-3148-z

Robinson CJ, Bark RH, Garrick D, Pollino CA (2015) Sustaining local values through river basin governance: community-based initiatives in Australia’s Murray–darling basin. J Environ Plan Manag 58:2212–2227. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2014.976699

Robinson CJ, Margerum RD, Koontz TM, Moseley C, Lurie S (2011) Policy-level collaboratives for environmental management at the regional scale: lessons and challenges from Australia and the United States. Soc Nat Resour 24:849–859. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2010.487848

Robinson CJ, Taylor B, Vella K, Wallington T (2014) Working knowledge for collaborative water planning in Australia’s wet tropics region. Int J Water Gov 2:43–60. https://doi.org/10.7564/13-IJWG4

Sarkki S, Tinch R, Niemelä J, Heink U, Waylen K, Timaeus J, Young J, Watt A, Neßhöver C, van den Hove S (2015) Adding ‘iterativity’ to the credibility, relevance, legitimacy: a novel scheme to highlight dynamic aspects of science–policy interfaces. Environ Sci Pol 54:505–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.02.016

Simons M, Podger G, Cooke R (1996) IQQM—a hydrologic modelling tool for water resource and salinity management. Environ Softw 11:185–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0266-9838(96)00019-6

Susskind L, Cruikshank JL (1987) Breaking the impasse: consensual approaches to resolving public disputes. Basic Books, New York

USBR (2000) Colorado River interim surplus criteria final environmental impact statement. U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington DC

USBR (2007) Colorado River interim guidelines for lower basin shortages and the coordinated operations for Lake Powell and Lake Mead final environmental impact statement. U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington DC

USBR (2012) Colorado River basin water supply and demand study. U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington DC

van Asselt MBA, Rotmans J (2002) Uncertainty in integrated assessment modelling. Clim Chang 54:75–105. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1015783803445

Van den Belt M (2004) Mediated modeling: a system dynamics approach to environmental consensus building. Island press, Washington DC

Walker G, Gilfedder M, Evans W, Dyson P, Stauffacher M (2003) Groundwater flow systems framework: essential tools for planning salinity management vol MDBC Publication 14/03, Canberra,

Weichselgartner J, Kasperson R (2010) Barriers in the science-policy-practice interface: toward a knowledge-action-system in global environmental change research. Glob Environ Chang 20:266–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.11.006

Welsh WD, Black D (2010) Engaging stakeholders for a software development project: river manager model. In: Modelling for Environment’s sake: proceedings of the 5th Biennial Conference of the International Environmental Modelling and Software Society, iEMSs 2010, 2010. pp 539–546

Welsh WD, Vaze J, Dutta D, Rassam D, Rahman JM, Jolly ID, Wallbrink P, Podger GM, Bethune M, Hardy MJ, Teng J, Lerat J (2013) An integrated modelling framework for regulated river systems. Environ Model Softw 39:81–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2012.02.022

Westfall B, Bliesner R (2006) Memorandum: model runs with new operating rules that focus on maximizing high flow days. Keller-Bliesner Engineering, Logan UT, p 4

Wheeler KG, Basheer M, Mekonnen ZT, Eltoum SO, Mersha A, Abdo GM, Zagona EA, Hall JW, Dadson SJ (2016) Cooperative filling approaches for the grand Ethiopian renaissance dam. Water Int 41:611–634. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2016.1177698

Wheeler KG, Pitt J, Magee TM, Luecke DF (2007) Alternatives for restoring the Colorado river delta. Nat Resour J 47:917. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24889540

White DD, Wutich A, Larson KL, Gober P, Lant T, Senneville C (2010) Credibility, salience, and legitimacy of boundary objects: water managers’ assessment of a simulation model in an immersive decision theater. Sci Public Policy 37:219–232. https://doi.org/10.3152/030234210X497726

Zagona EA, Fulp TJ, Shane R, Magee T, Goranflo HM (2001) RiverWare: a generalized tool for complex reservoir systems modeling. J Am Water Resour Assoc 37:913–929. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-1688.2001.tb05522.x

Zeitoun M, Warner J (2006) Hydro-hegemony-a framework for analysis of trans-boundary water conflicts. Water Policy 8:435–460. https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2006.054

Acknowledgements

We thank the Distinguished Visiting Scientist program of CSIRO, CSIRO Land and Water, and the Sustainability Science Program of the Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government in the Harvard Kennedy School of Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval by the University of Oxford (SOGE 15 1A 16) and CSIRO (111/13) was obtained for this research.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PDF 729 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wheeler, K.G., Robinson, C.J. & Bark, R.H. Modelling to bridge many boundaries: the Colorado and Murray-Darling River basins. Reg Environ Change 18, 1607–1619 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-018-1304-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-018-1304-z