Abstract

Adaptation to a changing climate is unavoidable. Mainstreaming climate adaptation objectives into existing policies, as opposed to developing dedicated adaptation policy, is widely advocated for public action. However, knowledge on what makes mainstreaming effective is scarce and fragmented. Against this background, this paper takes stock of peer-reviewed empirical analyses of climate adaptation mainstreaming, in order to assess current achievements and identify the critical factors that render mainstreaming effective. The results show that although in most cases adaptation policy outputs are identified, only in a minority of cases this translates into policy outcomes. This “implementation gap” is most strongly seen in developing countries. However, when it comes to the effectiveness of outcomes, we found no difference across countries. We conclude that more explicit definitions and unified frameworks for adaptation mainstreaming research are required to allow for future research syntheses and well-informed policy recommendations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

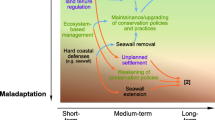

Despite agreements made in December 2015 during the COP21 in Paris to reduce CO2 emissions, intensified adaptation efforts are needed to deal with the impacts of a changing climate. As a consequence, adaptation to climate change is considered necessary by many policy-makers and scholars, particularly in policy sectors such as critical infrastructure, agriculture, public health and urban planning (Wamsler 2014; Albers et al. 2015; Wamsler and Pauleit 2016). In order to do so, policy-makers and planners basically have two options, which are mutually supportive: mainstreaming (integrating) climate change adaptation objectives into existing sectoral policies and practices, or the “dedicated approach”: developing stand-alone adaptation policies and programmes (Wamsler 2014; Uittenbroek 2014; Dewulf et al. 2015).

Literature suggests that mainstreaming climate adaptation objectives into existing policies and practices has several advantages for achieving sustainable change. First, mainstreaming can create synergy effects; for instance, greening urban spaces not only reduces the risk of pluvial flooding (which is expected to intensify as a consequence of climate change) but also contributes to spatial quality, biodiversity and climate change mitigation (Runhaar et al. 2012). Second, mainstreaming adaptation objectives in sectoral plans and policies may be more resource-efficient from an administrative and budgetary point of view (Kok and De Coninck 2007). For instance, “windows of opportunity” can be used for adaptation mainstreaming, such as the construction of new roads or the restructuring of city centres. Third, mainstreaming climate adaptation in existing policies or organisational structures may result in more effective adaptation measures, e.g. if climate risks are included in urban (re)design (Wamsler 2014). Finally, such mainstreaming may promote innovation in sectoral policies and plans (Adelle and Russel 2013). However, mainstreaming as a policy strategy has also been critiqued, particularly because of the risks of diminishing issue visibility and attention (Persson et al. 2016) and policy “dilution” (Liberatore 1997), when compared with a dedicated approach that relies on highly specialised institutional responsibilities, dedicated funds and a clear legal framework.

Climate adaptation mainstreaming requires targeted strategies and action, beyond mere aspirations, to be effective and to overcome potential barriers (e.g. Uittenbroek 2016). While a recent review of the National Communications submitted under the UNFCCC reported a higher number of adaptation initiatives and mainstreaming in almost all policy sectors in 2014 compared with 2010 (Lesnikowski et al. 2016), there are considerable differences in progress across countries, sectors and policy levels (cf. Reckien et al. 2014; Dewulf et al. 2015; Wamsler 2015). Meta-analyses that have systematically assessed mainstreaming achievements, drivers, barriers and associated theory development are largely lacking (Jordan and Lenschow 2008; Runhaar et al. 2014).

Against this background, this paper takes stock of peer-reviewed empirical analyses of climate adaptation mainstreaming in order to (a) identify what mainstreaming practices have so far achieved and through what strategies; (b) identify what differences can be discerned between policy sectors and countries; and (c) identify the critical factors that render mainstreaming effective. A systematic literature review of existing empirical studies is carried out to assess the growing literature on adaptation mainstreaming.

Analytical framework

In this section, we define key concepts and present the approach taken for our systematic literature review. The framework is based on literature on climate adaptation mainstreaming and environmental policy integration (EPI; see e.g. Lafferty and Hovden 2003; Jordan and Lenschow 2008; Persson et al. 2016), since mainstreaming can be seen as a specific manifestation of the EPI (Adelle and Russel 2013; Massey and Huitema 2013; Runhaar et al. 2014).

Climate adaptation mainstreaming has no agreed-upon definition (Brouwer et al. 2013). In the literature as well as in policy practice, different meanings, assumptions and objectives are associated with climate adaptation mainstreaming (Adelle and Russel 2013). The IPCC AR5 WGII report uses the term adaptation mainstreaming for denoting increasing adaptation planning and implementation within government, regardless of whether through a sectoral integration approach or a dedicated approach (IPCC 2014, pp. 871–888). Massey and Huitema (2013) consider mainstreaming “(…) a mode or a means of implementing adaptation policies and activities” (ibid, p. 345). In other words, climate adaptation policy forms a new policy field, and mainstreaming is considered a means to implement that new policy at different levels and in different sectors. Authors such as Uittenbroek et al. (2014) and Dewulf et al. (2015), however, explicitly distinguish mainstreaming from dedicated adaptation policy, while Wamsler and Pauleit (2016) see dedicated adaptation policies as an integral element of adaptation mainstreaming. Different authors thus mean different things with mainstreaming.

Rather than limiting ourselves to a particular definition or perspective, in our review, we explicitly examine how in the literature mainstreaming is defined (and distinguished from a dedicated approach) and thus “measured”. In this way, we aim to contribute to more transparency about the concept and facilitating consistency of its use. Accordingly, we analyse differences in the pursued mainstreaming strategies by linking them to the mainstreaming strategies identified by Wamsler and Pauleit (2016):

-

Programmatic mainstreaming: the modification of the implementing body’s sector work by integrating aspects related to adaptation into on-the-ground operations, projects or programmes;

-

Managerial mainstreaming: the modification of managerial and working structures, including internal formal and informal norms and job descriptions, the configuration of sections or departments, as well as personnel and financial assets, to better address and institutionalise aspects related to adaptation;

-

Intra- and inter-organisational mainstreaming: the promotion of collaboration and networking with other departments, individual sections or stakeholders (i.e. other governmental and non-governmental organisations, educational and research bodies and the general public) to generate shared understandings and knowledge, develop competence and steer collective issues of adaptation;

-

Regulatory mainstreaming: the modification of formal and informal planning procedures, including planning strategies and frameworks, regulations, policies and legislation, and related instruments that lead to the integration of adaptation;

-

Directed mainstreaming: higher level support to redirect the focus to aspects related to mainstreaming adaptation by e.g. providing topic-specific funding, promoting new projects, supporting staff education or directing responsibilities.

The authors mention a sixth strategy that refers to the dedicated approach to climate adaptation (labelled by them as “add-on mainstreaming”) and that is thus excluded from our framework.

There is no widely accepted agreement about what mainstreaming is to achieve, i.e. when it is effective, and how this could be measured, either (cf. Brouwer et al. 2013). This includes questions about the relative weight and priority adaptation objectives are given in comparison to sectoral objectives (Adelle and Russel 2013; see also Lafferty and Hovden 2003). Stated differently: to what extent should climate risk be reduced, i.e. what are acceptable risk levels? (Runhaar et al. 2016). These are problematic questions because they cannot be answered objectively. In this paper we define effectiveness of adaptation mainstreaming (i.e. the dependent variable) in terms of policy outputs as well as policy outcomes (cf. Persson 2007; Jordan and Lenschow 2008). Policy outputs here include the adoption of formal adaptation goals in sectoral policies (e.g. the goal to anticipate and reduce risk of intensified heat stress in spatial plans), procedural instruments (e.g. formal reporting requirements, cooperation), and changes in institutional structures (e.g. creation of new inter-sectoral working groups). Policy outcomes are a step further and refer to development and implementation of concrete local and national adaptation measures (including heatwave plans, early warning systems, continuity plans, embankments and other physical measures), as a response to policy outputs. Evaluating these outputs and outcomes is challenging (see e.g. Dupuis and Biesbroek 2013) although nominal measures can be used as a proxy (cf. Lesnikowski et al. 2016). In addition, our analytical framework takes a step further, including the assessment of the effectiveness of policy outputs, based on how they were described and interpreted by the authors of the articles we have reviewed (see Annex 2).

Explaining the extent to which climate adaptation mainstreaming is successful in terms of producing outputs and outcomes that can be considered as effective requires insight into mainstreaming drivers and barriers. Previous studies have identified these factors from various perspectives. The following categories are typically identified:

-

Political factors: interests that align or conflict with adaptation goals, level of political commitment to adaptation, level of public awareness of or support for adaptation, policy (in)consistency across policy levels, flexibility of legislative and policy context, and level of political stability (e.g. Stead and Meijers 2009; Runhaar et al. 2012; Dupon and Oberthür 2012; Uittenbroek et al. 2014; Wamsler and Pauleit 2016);

-

Organisational factors: factors within particular organisations as well as inter-organisational factors. Examples include formal requirements or incentives to develop sectoral adaptation plans, presence or absence of a supportive regulative framework (i.e. supportive legislation, regulation), (expanded) mandates and statutes, (a lack of) coordination and cooperation between government departments (within or across policy sectors), coordination among policy levels, cooperation with private actors, clarity about responsibilities for adaptation (problem ownership), level of institutional fragmentation, organisational structures, routines and practices, and administrative leadership (e.g. Persson 2007; Stead and Meijers 2009; IPCC 2014; Wamsler 2014; Uittenbroek 2016);

-

Cognitive factors: level of awareness, level of uncertainty, sense of urgency, and degree of social learning (Persson 2007; Runhaar et al. 2012; Biesbroek et al. 2013; Wamsler and Pauleit 2016);

-

Resources: available staff, financial resources, subsidies from higher levels of government, information and guidance, and availability of and access to knowledge and expertise (e.g. Stead and Meijers 2009; Runhaar et al. 2012; Ekstrom and Moser 2014; Uittenbroek et al. 2014; Wamsler and Pauleit 2016);

-

Characteristics of the adaptation problem at issue: the way in which the adaptation objective is framed and linked to sectoral objectives, level of detail in which adaptation objectives are defined and compatibility of time scales (Persson 2007; Runhaar et al. 2012; Biesbroek et al. 2013; Ekstrom and Moser 2014);

-

Timing: waiting and sustaining momentum for climate adaptation, focussing events, and windows of opportunity such as urban renewal (e.g. Runhaar et al. 2012; Wamsler 2015; Uittenbroek 2016).

Methods

Methods used for applying our analytical framework are described in detail in Annexes 1 and 2. In brief, a systematic, in-depth literature review was conducted of peer-reviewed papers (n = 87) that reported on empirical analysis of climate adaptation mainstreaming practices. Figure 1 visualises the stepwise approach taken for the selection of papers. The papers, selected from the Scopus database (end 2016), reported on 140 cases of mainstreaming practices. A “case” represents here a mainstreaming practice in a single country (at national, regional or local level; no cases referred to mainstreaming in a transboundary or supranational context). In various papers that reported on international comparisons of mainstreaming practices or multiple cases, it was not possible to differentiate distinctive mainstreaming practices in terms of our analytical framework to a specific country because the evidence was presented at a too abstract level. Therefore, not all 140 cases are included in all analyses. The majority of cases are European (n = 71, as opposed to 51 cases in non-European developing countries and 18 in non-European developed countries). Europe is thus over-represented in adaptation mainstreaming research. For the analyses we used qualitative coding and descriptive statistics. Annex 2 describes in detail how we have operationalised our analytical framework through a coding scheme.

Reviewing the evidence: what works?

Our results reveal that there has been a rapidly growing interest in studying adaptation mainstreaming over the past decade (see Annex 3), which also might indicate an increase in actual cases of mainstreaming practices.

Mainstreaming definitions and interpretations

Regarding the different definitions and interpretations of mainstreaming used, we find that 70% of the reviewed papers provide an explicit definition of adaptation mainstreaming (see Annex 4 for an overview of definitions). However, in only 40% of the papers an explicit framework for analysing or operationalising mainstreaming is applied. Some papers have adopted the use of key criteria for integrated policies proposed by Mickwitz et al. (2009). In other papers, mainstreaming is analysed in terms of different mainstreaming strategies similar to those proposed by Wamsler and Pauleit (2016). The fact that 60% of the papers did not employ an explicit framework for analysing or operationalising mainstreaming suggests that there is ample scope for more specific definitions and explicit operationalisations as well as more unified operationalisation in order to facilitate comparative analysis, policy recommendations and learning.

In just more than half of the papers, mainstreaming is explicitly distinguished from a dedicated adaptation approach. Twelve papers that made such explicit distinction (14% of all papers) report on experiences with both approaches to climate adaptation. For instance, Stiller and Meijerink (2016) and Wamsler (2015) describe the employment of climate adaptation officers via climate-related funding (dedicated approach) to facilitate the integration of climate adaptation as a central theme in sector development planning and work streams of sub-regional, local administrations (mainstreaming) in Germany. Another example of such a mixed, or nested, approach are national or municipal adaptation plans (representing a dedicated approach) that include provisions to mainstream climate adaptation objectives into sectoral policies and plans, as outlined by Biesbroek et al. (2010), Saito (2013) and Wamsler (2015). Again, these results show the importance of more precise and consistent terminology to facilitate comparative analysis, policy recommendations and learning.

What is mainstreamed into what?

Looking at the policy level of mainstreaming practices studied, our results show that adaptation mainstreaming has mainly taken place at national government level (39%) and local government level (35%). The national level thus gets the most attention, despite the fact that municipalities or cities are increasingly seen as the key stakeholders in adaptation planning (Bulkeley and Betsill 2013). In terms of substantive focus, in the reviewed cases the climate risks in focus are flooding, changing temperatures, and extreme heat and cold. However, there is quite an even spread among these three and other categories (e.g. extreme weather events in general, drought and water scarcity, sea level rise and erosion), meaning that there is no clear pattern. Finally, in terms of policy sectors in which adaptation objectives are mainstreamed, the most dominant ones are environmental and natural resources management (including agriculture, coastal zone management, environmental management, nature and biodiversity conservation and green infrastructure), followed by urban/regional (land use) planning, water/flood risk management, and crisis management and risk reduction planning (Fig. 2). In contrast, there are fewer reports of climate adaptation mainstreaming in critical infrastructures such as water supply and sanitation, housing, transportation and telecommunications, despite their widely-recognised importance (Runhaar et al. 2016; IPCC 2014). Surprisingly, housing, transport and telecommunications are relatively less subject to mainstreaming than other policy sectors. Yet, with their typically long planning and investment horizons (meaning that climate proofing is particularly critical), housing, transport and telecommunications are sectors that merit more attention for adaptation mainstreaming.

Mainstreaming strategies

During the coding of the papers it appeared that the strategy of “programmatic mainstreaming” posed problems because it was difficult to distinguish this strategy from its achievements in terms of policy outputs and outcomes. Therefore it was ignored in the analysis. Considering the remaining strategies, our results show that regulatory mainstreaming (which ranges from including climate adaptation as an objective in sectoral policy documents to changes in strategic planning and legislative tools), is the most frequently reported strategy (86% of cases). The relatively lower frequency of managerial (73%) and intra- and inter-organisational (54%) mainstreaming suggests that more practical approaches are still lacking, i.e. how to achieve a stated policy aspiration or requirement in practice. In addition, directed mainstreaming (that is, higher level support to redirect the focus to aspects related to mainstreaming adaptation by e.g., providing topic-specific funding, promoting new projects, supporting staff education, or directing responsibilities) is least reported (37%). This suggests that mainstreaming is often a rather informal activity that is pushed by local needs and bottom-up processes rather than pushed by higher level authorities (cf. Wamsler 2015). Looking at the adoption of mainstreaming strategies over time, they follow a similar curve (peaking in 2010, but likely due to the time period selected for inclusion of papers) which suggests that relative preferences have not changed over time.

Mainstreaming effectiveness—outputs and outcomes

In most of the cases (98%), it was reported that mainstreaming had led to policy outputs, whereas policy outcomes were reported in only half of the cases (51%). Scoring the outputs and outcomes in terms of whether they were seen by the authors to represent effective, partly effective or ineffective mainstreaming, the results clearly show that mainstreaming has been more successful in producing effective policy outputs than effective outcomes (Fig. 3). This means that the literature finds adaptation mainstreaming more effectively addressed in sector policy documents and plans, than in concrete projects and activities. In other words, there seems to be an implementation gap in translating mainstreamed sectoral policies into concrete adaptation on the ground.

Further, qualitative assessment of the identified outputs and outcomes suggests that effective outputs were mainly reported when several mainstreaming strategies were employed simultaneously and when higher-level changes were operationalised at local level, for instance, into the set-up of functional, supportive municipal structures, enshrining climate adaptation in local programming, enhanced coordination and collaboration of stakeholders, or the renegotiation of responsibilities (Stiller and Meijerink 2016). Unfortunately, the number of papers in which single strategies were reported was too small for an analysis of relative effectiveness of mainstreaming strategies.

Zooming in on the most prominent policy sectors (n > 20) we found that not only the number of strategies employed but also their composition are decisive factors for effective mainstreaming (measured in terms of policy outputs), irrespective of the sector (see Annex 5). The majority of success cases across all four sectors exhibits a combination of managerial, intra- and inter-organisational, and regulatory mainstreaming (90% in environmental and natural resources management, 82% in crisis management, 74% in urban planning, and 65% in water and flood risk management). Directed mainstreaming would seem a powerful strategy to promote climate adaptation mainstreaming, but is less prevalent in cases with effective policy outputs, which can be explained by our finding that it is the least observed strategy. Possibly absence of directed mainstreaming can be compensated by employing multiple other strategies.

A comparison of whether mainstreaming has been effective or partly effective at the policy output level across our three country groupings shows that Europe has the largest share in effective outputs (70%, compared with 52% of all outputs observations) (Fig. 3). Developing countries show the largest share of partly effective mainstreaming outputs, which suggests that robust mainstreaming strategies are yet to mature and that developing countries have comparatively greater difficulties to sustain adaptation practices.

The situation is quite different, and the picture more unified, when we compare policy outcomes across country groups. In fact, effective outcomes are low in numbers across all country groups. The relatively high frequency of partly effective outcomes across all country groups (developed or developing) suggests that crossing the threshold between pilot projects and institutionalisation of practices is difficult, no matter what region or context.

Mainstreaming drivers and barriers

What explains these mainstreaming achievements and ‘what works’? Our literature review looked at drivers and barriers mentioned in the analysed cases that report on both outputs and outcomes, in a similar way as Biesbroek et al. (2013) did for adaptation in general. Our analytical framework (see “Analytical framework” section) includes 32 factors that can promote or inhibit mainstreaming, grouped in six categories (see “Analytical framework” section).

Our results show that the most often mentioned drivers are, in order: political commitment; cooperation with private actors; the presence of policy entrepreneurs; focusing events; and lastly subsidies from higher levels of government which is on par with framing and linking to sectoral objectives (see Table 1). While the importance of political commitment and external cooperation is thus recognised, it is not reflected in practice (with directed and inter-organisational mainstreaming being the least reported strategies). While the mentioned drivers are also found in much literature on general EPI, the role of (a) cooperation with private actors and (b) focusing events appears to be more crucial in this specific context of climate adaptation mainstreaming. The importance of the latter stems from the perceived urgency and enhanced public and stakeholder support for adaptation action after climate events (“focusing event”), although we expect this so-called window of opportunity to be generally very short-lived.

The most frequently reported barriers are lack of: financial resources, information, guidance, coordination and cooperation between departments, staff resources and access to adaptation knowledge and expertise as well as conflicting interests. Note that some factors (e.g. coordination/cooperation between government departments, and information and guidance) are almost as often reported to be drivers as barriers, which suggests they are particularly important to get right. The importance of good coordination and cooperation between government departments contrasts with the identified mainstreaming strategies, in that intra-organisational mainstreaming was not reported as a common strategy while forming an integrative part of success cases (see above). Also for the cases scored as yielding effective policy outputs (n = 50) a pattern emerges, which is similar to this picture. In sum, while the identified drivers and barriers match the key attributes of the different mainstreaming strategies (see “Analytical framework” section), and in turn support the identified importance of employing multiple strategies for effective outputs (see above), current practice is lagging behind.

Learning from mainstreaming failure

An analysis of “what works” is incomplete without learning from the cases where mainstreaming has failed. Therefore, we take a closer look at prominent barriers reported in those cases where outputs did not translate into implementation of adaptation measures. These may provide explanations why ensuring outcomes from mainstreaming strategies are experienced as a challenge, which applies across all country groups. We decided against further comparing these cases with the ones that reported on ineffective outcomes, since the sample was too small to be conclusive.

As could be expected from their relative importance in the successful cases, the most frequently mentioned barriers for cases where outputs did not translate into implementation are: a lack of coordination and cooperation between departments within and across policy domains, closely followed by a lack of financial resources (see Annex 6). These further support above-mentioned explanations for directed and inter-organisational mainstreaming being the least reported strategies and underline their importance for both outputs and outcomes. Additional factors scoring high as barriers are: the absence of clear mandates, conflicting political interests, and organisational structures, routines, and practices. Overall, most of the dominant barriers to implementation are found in organisational factors (linked to managerial and inter-organisational mainstreaming) and, to a lesser extent, in the resources and cognitive categories. In contrast, factors that we classified within the timing and political categories (except for conflicting interests) seem to play a subordinate role as these were least often mentioned. Furthermore, access to expertise and information and guidance are not among the prominent barriers. This suggests that the implementation gap is not primarily an issue of lack of knowledge or financial resources, but first of all needs to be addressed by reviewing inner-organisational structures, practices and ways of collaboration both internally and externally. In other words, practitioners do seem to have the knowledge about potential adaptation measures but are experiencing trouble putting them into practice within existing structures.

Discussion and conclusions: advancing adaptation mainstreaming

Because progress in climate adaptation is commonly considered to be slow, past research has strongly focused on identifying adaptation barriers. However, this “barrier-focused” type of research has been increasingly criticised since it oversimplifies adaptation planning and decision-making processes (Biesbroek et al. 2015). In view of the need for “opening up the black box of adaptation decision-making” (Biesbroek et al. 2015), our meta-analysis offers a more nuanced study by analysing mainstreaming as a specific approach to adaptation planning, including distinctive strategies as well as achievements in terms of policy outputs and outcomes.

Our results show, first, that the analysis and operationalisation of mainstreaming is diverse, often limited and inconsistent. This limits learning from others and with that, effective mainstreaming. Hence, we call for more explicit and systematic conceptualisation of adaptation mainstreaming in practice and research. We suggest to measure climate mainstreaming in terms of policy outputs and outcomes, in other words, the extent of “climate proofing” of a policy sector, because this is ultimately the aim. The often-employed definition (or better: description) of mainstreaming in terms of the incorporation of climate adaptation objectives into sectoral policies is too vague and does not make clear what the focus is: on the process of mainstreaming or on its results. In order to learn from mainstreaming practices it is important to identify strategies that have been employed as well as barriers and enablers. For that purpose our study offers a replicable framework for systematically assessing and supporting future progress in adaptation mainstreaming.

Second, our results show that the identified implementation gap of adaptation mainstreaming relates mainly to a lack of a sustained political commitment for adaptation mainstreaming from higher levels, and the lack of effective cooperation and coordination between key stakeholders. A focusing event may temporarily increase momentum, but it fails to secure institutionalised routines and practices for mainstreaming. We found that so-called directed mainstreaming, that is higher-level support for mainstreaming and/or higher-level mainstreaming requirements, are among the least reported strategies for promoting mainstreaming, rendering mainstreaming a rather voluntary activity that is faced with numerous implementation barriers. Based on our findings we expect that more strict requirements for mainstreaming, set at the national or international level, will provide an important impetus for policy-makers and planners in non-climate policy sectors and at lower tiers of government to climate proof the sectors they bear responsibility for. These requirements should be combined with the provision of sufficient resources in order to overcome implementation barriers. A more active involvement of civil society and private sector could help maintain climate adaptation on the policy agenda and increase political stakes.

References

Adelle C, Russel D (2013) Climate policy integration: a case of déjà vu? Environ Policy Gov 23(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1601

Albers RAW, Bosch PR, Blocken B, van den Dobbelsteen AAJF, van Hove LWA, Spit TJM, van de Ven F, van Hooff T, Rovers V (2015) Overview of challenges and achievements in the climate adaptation of cities and in the climate proof cities program (Editorial). Build Environ 83:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2014.09.006

Biesbroek GR, Klostermann JEM, Termeer CJAM, Kabat P (2013) On the nature of barriers to climate change adaptation. Reg Environ Chang 13(5):1119–1129. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-013-0421-y

Biesbroek R, Dupuis J, Jordan A, Wellstead A, Howlett M, Cairney P, Rayner J, Davidson D (2015) Opening up the black box of adaptation decision-making. Nat Clim Chang 5(6):493–494. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2615

Brouwer S, Rayner T, Huitema D (2013) Mainstreaming climate policy: the case of climate adaptation and the implementation of EU water policy. Environ Plan C: Gov Policy 31(1):134–153. https://doi.org/10.1068/c11134

Bulkeley H, Betsill MM (2013) Revisiting the urban politics of climate change. Environ Polit 22(1):136–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2013.755797

Dewulf A, Meijerink S, Runhaar H (2015) Editorial for the special issue on the governance of adaptation to climate change as a multi-level, multi-sector and multi-actor challenge: a European comparative perspective. J Water Clim Chang 6(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.2166/wcc.2014.000

Dupon C, Oberthür S (2012) Insufficient climate policy integration in EU energy policy: the importance of the long-term perspective. J Contemp Eur Res 8:228–247

Dupuis J, Biesbroek R (2013) Comparing apples and oranges: the dependent variable problem in comparing and evaluating climate change adaptation policies. Glob Environ Chang 23(6):1476–1487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.07.022

Ekstrom JA, Moser SC (2014) Identifying and overcoming barriers in urban climate adaptation: case study findings from the San Francisco Bay Area, California, USA. Urban Clim 9:54–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2014.06.002

IPCC (2014) Climate Change 2014: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part A: global and sectoral aspects. Contribution of working group II to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Jordan A, Lenschow A (2008) Integrating the environment for sustainable development: an introduction. In: Jordan AJ, Lenschow A (eds) Innovation in environmental policy? Edward Elgar, Integrating the environment for sustainable development. Cheltenham, pp 3–23. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781848445062.00012

Kok MTJ, de Coninck HC (2007) Widening the scope of policies to address climate change: directions for mainstreaming. Environ Sci Policy 10(7-8):587–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2007.07.003

Lafferty WM, Hovden E (2003) Environmental policy integration: towards an analytical framework. Environ Polit 12(3):1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644010412331308254

Lesnikowski A, Ford J, Biesbroek R, Berrang-Ford L, Heymann SJ (2016) National-level progress on adaptation. Nat Clim Chang 6(3):261–264. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2863

Liberatore A (1997) The integration of sustainable development objectives into EU policy-making: barriers and prospects. In: Baker S, Kousis M, Richardson D, Young S (eds) The politics of sustainable development: theory, policy and practice within the European Union. Routledge, London/New York, pp 107–126

Massey E, Huitema D (2013) The emergence of climate change adaptation as a policy field: the case of England. Reg Environ Chang 13(2):341–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-012-0341-2

Mickwitz P, Aix F, Beck S, Carss D, Ferrand N, Görg C, Jensen A, Kivimaa P, Kuhlicke C, Kuindersma W, Máñez M, Melanen M, Monni S, Branth Pedersen A, Reinert H, van Bommel S (2009) Climate policy integration, coherence and governance. Helsinki, Partnership for European Environmental Research https://bio-city-leipzig.inqbus.de/news-de/1m235-peer-report2.pdf

Persson Å (2007) Different perspectives on EPI. In: Nilsson M, Eckerberg K (eds) Environmental policy integration in practice: shaping institutions for learning. Earthscan, London, pp 25–48

Persson Å, Eckerberg K, Nilsson M (2016) Institutionalization or wither away? 25 years of environmental policy integration under shifting governance models in Sweden. Environ Plan C 34(3):478–495. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X15614726

Reckien D, Flacke J, Dawson RJ, Heidrich O, Olazabal M, Foley A, Hamann JJ-P, Orru H, Salvia M, de Gregorio Hurtado S, Geneletti D (2014) Climate change response in Europe: what’s the reality? Analysis of adaptation and mitigation plans from 200 urban areas in 11 countries. Clim Chang 122(1-2):331–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-013-0989-8

Runhaar H, Mees H, Wardekker A, van der Sluijs J, Driessen P (2012) Adaptation to climate change related risks in Dutch urban areas: stimuli and barriers. Reg Environ Chang 12(4):777–790. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-012-0292-7

Runhaar H, Driessen P, Uittenbroek C (2014) Towards a systematic framework for the analysis of environmental policy integration. Environ Policy Gov 24(4):233–246. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1647

Runhaar H, Uittenbroek C, van Rijswick M, Mees H, Driessen P, Gilissen HK (2016) Prepared for climate change? A method for the ex-ante assessment of formal responsibilities for climate adaptation in specific sectors. Reg Environ Chang 16(5):1389–1400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-015-0866-2

Saito N (2013) Mainstreaming climate change adaptation in least developed countries in South and Southeast Asia. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Chang 18(6):825–849. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-012-9392-4

Stead D, Meijers E (2009) Spatial planning and policy integration: concepts, facilitators and inhibitors. Plan Theory Pract 10(3):317–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649350903229752

Stiller S, Meijerink S (2016) Leadership within regional climate change adaptation networks: the case of climate adaptation officers in Northern Hesse, Germany. Reg Environ Chang 16(6):1543–1555. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-015-0886-y

Uittenbroek CJ (2014) How mainstream is mainstreaming? The integration of climate adaptation in urban policy, PhD thesis, Utrecht, Utrecht University

Uittenbroek CJ, Janssen-Jansen LB, Spit TJ, Runhaar HAC (2014) Organizational values and the implications for mainstreaming climate adaptation in Dutch municipalities: using Q methodology. J Water Clim Chang 5(3):443–456. https://doi.org/10.2166/wcc.2014.048

Uittenbroek CJ (2016) From policy document to implementation: organizational routines as possible barriers to mainstreaming climate adaptation. J Environ Policy Plan 18(2):161–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2015.1065717

Wamsler C (2014) Cities, disaster risk, and adaptation. Routledge, London

Wamsler C (2015) Mainstreaming ecosystem-based adaptation: transformation toward sustainability in urban governance and planning. Ecol Soc 20(2):30. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-07489-200230

Wamsler C, Pauleit S (2016) Making headway in climate policy mainstreaming and ecosystem-based adaptation: two pioneering countries, different pathways, one goal. Clim Chang 137(1-2):71–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-016-1660-y

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Editor: Robbert Biesbroek.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 242 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Runhaar, H., Wilk, B., Persson, Å. et al. Mainstreaming climate adaptation: taking stock about “what works” from empirical research worldwide. Reg Environ Change 18, 1201–1210 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-017-1259-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-017-1259-5