Abstract

Potential trade-offs between providing sufficient food for a growing human population in the future and sustaining ecosystems and their services are driven by various biophysical and socio-economic parameters at different scales. In this study, we investigate these trade-offs by using a three-step interdisciplinary approach. We examine (1) how the expected global cropland expansion might affect food security in terms of agricultural production and prices, (2) where natural conditions are suitable for cropland expansion under changing climate conditions, and (3) whether this potential conversion to cropland would affect areas of high biodiversity value or conservation importance. Our results show that on the one hand, allowing the expansion of cropland generally results in an improved food security not only in regions where crop production rises, but also in net importing countries such as India and China. On the other hand, the estimated cropland expansion could take place in many highly biodiverse regions, pointing out the need for spatially detailed and context-specific assessments to understand the possible outcomes of different food security strategies. Our multidisciplinary approach is relevant with respect to the Sustainable Development Goals for implementing and enforcing sustainable pathways for increasing agricultural production, and ensuring food security while conserving biodiversity and ecosystem services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Halving the proportion of undernourished people in the developing countries by 2015 was one of the objectives of the United Nation’s Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). The prevalence of undernourishment was reduced between the periods 1990–1992 and 2012–2014 from 18.7 to 11.3 % globally and from 23.4 to 13.5 % in developing countries in the same period of time (FAO et al. 2014). However, the 2014 MDG report argues that while this target has been met on a global scale, South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa are lacking behind (United Nations 2014). Therefore, the challenge of meeting food security goals is likely to persist in the future.

With a world population that is expected to grow from currently about 6.9–9.2 billion by 2050, as well as changing lifestyles and consumption patterns towards more protein-containing diets, global demand for food is projected to increase by 70–110 % by 2050 (Bruinsma 2011; Kastner et al. 2012; Tilman et al. 2011). In order to ensure sufficient food supply in the coming decades, several solutions are suggested. Besides reducing food waste and harvest losses, improving food distribution and access, and shifting diets towards consumption of fewer meat and dairy products, studies conclude that also the increase in global agricultural production is crucially important to meet the increasing demand (Garnett et al. 2013; Godfray et al. 2010; Gregory and George 2011; Gustavsson et al. 2011; Ray and Foley 2013; Mauser et al. 2015). At the same time, agricultural yields as well as production stability are affected by climate change, albeit study results vary between different approaches and assumptions (IIASA and FAO 2012; Rosenzweig et al. 2013; van Ittersum et al. 2013).

The possibilities to increase agricultural production consist of intensification of existing croplands and of their expansion into uncultivated areas, but both options are associated with environmental externalities, including the pollution of surface and groundwater by agrochemicals, unsustainable water withdrawals, and the loss of biodiversity (Foley et al. 2011). Biodiversity loss due to agricultural activities is particularly worrisome because it has consequences for ecosystem functioning, provisioning of ecosystem services, resilience of social–ecological systems, and ultimately the welfare of human societies (Corvalan et al. 2005). These potential trade-offs are clearly reflected in the recently published Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). They highlight the topic of food security and sustainable agriculture (UN 2012), but compared to the MDGs which were restricted to socio-economic goals, they stress the need to ensure the protection, regeneration and resilience of global and regional ecosystems (ibid §4).

Land-use intensification has been variously shown to negatively impact local biodiversity in many regions of the world (Flynn et al. 2009; Newbold et al. 2015). However, land-use expansion with its associated loss and fragmentation of natural habitats is the globally more dominant driver of biodiversity loss, particularly in highly biodiverse tropical and subtropical regions (Foley et al. 2005; Hosonuma et al. 2012; Pereira et al. 2012). Despite the negative externalities of cropland expansion and continuing calls for sustainable intensification (Garnett et al. 2013; Tilman 1999; West et al. 2014), the future expansion of agricultural land is still considered to be a likely scenario (see, e.g., the OECD/FAO Agricultural Outlook). Land productivity considerably increased over the last decades (FAOSTAT 2015). However, when neglecting future changes in cropping patterns and management, current yield trends of the most important staple crops are not sufficient to double global food production by 2050 (Ray et al. 2013). According to FAO, cropland is expected to globally expand by 7 % until 2030 (Alexandratos and Bruinsma 2012). Consequently, it is crucially important to examine (1) how the expected global cropland expansion might affect food security in terms of agricultural production and prices, (2) where natural conditions are suitable for cropland expansion under changing climate conditions, and (3) whether this potential conversion to cropland would affect areas of high biodiversity value or conservation importance. Answering these questions requires a scientific analysis of the trade-offs between achieving food security via cropland expansion on the one hand and conserving biodiversity on the other.

In this study, we investigate the trade-offs between providing sufficient food in the future and sustaining biodiversity by using a three-step interdisciplinary approach. First, we examine the impact of cropland expansion on food security in terms of agricultural production quantity and prices. In the following step, we identify areas that are biophysically most suitable for the potential expansion of cropland under specific climate scenario conditions. Finally, we use information on global patterns of endemism richness, in order to identify hot spots where biodiversity could be most affected by potential cropland expansion.

Methods and data

We use three different approaches to analyse trade-offs between food security and biodiversity since they are driven by various interdependent socio-economic and biophysical parameters that operate at different spatial scales. First, to address the impact of cropland expansion on global and regional agricultural markets we apply the computable general equilibrium model DART-BIO. The model accounts for socio-economic developments such as population growth and changes in consumption patterns, while it considers repercussions between different production sectors and regions, simulating the development of food quantity and prices as important indicators for food security. Second, since this approach does not allow for localizing cropland expansion, we use biophysical drivers at the local scale such as climate, soil quality, and topography to determine where an expansion of cropland potentially would be possible under the given natural conditions. Third, we use data on endemism richness, a biodiversity metric that represents the importance of an area for conservation, to statistically examine the spatial concordance between patterns of global biodiversity and potential cropland expansion.

The DART-BIO model

The Dynamic Applied Regional Trade (DART) model is a multi-sectoral, multi-regional recursive dynamic computable general equilibrium (CGE) model of the world economy. The DART model has been applied to analyse international climate policies (e.g. Springer 1998; Klepper and Peterson 2006a), environmental policies (e.g. Weitzel et al. 2012), energy policies (e.g. Klepper and Peterson 2006b), and agricultural and biofuel policies (e.g. Kretschmer et al. 2009) among others.

The DART model is based on data from the Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP) covering multiple sectors and regions. The economy in each region is modelled as a competitive economy with flexible prices and market-clearing conditions. The dynamic framework is recursively dynamic, meaning that the evolution of the economies over time is described by a sequence of single-period static equilibria connected through capital accumulation and changes in labour supply. The economic structure of DART is fully specified for each region and covers production, investment, and final consumption by consumers and the government.

DART is calibrated to the GTAP8 database (Narayanan et al. 2012) that represents production and trade data for 2007 with input–output tables for the world economy. The particular version used here (DART-BIO) contains 45 sectors and has detailed features concerning the agricultural sectors. Thirty-one activities in agriculture (thereof ten crop sectors) are explicitly modelled which represent a realistic picture of the complex value chains in agriculture. Several sectors that are only available on an aggregated level in the GTAP database are therefore split. The regional aggregation of 23 regions is chosen to include countries where main land use changes either due to biofuels production or because major changes in population, income, and consumption patterns are expected to emerge (e.g. Brazil, Malaysia, China). A detailed model description of the database and data processing can be found in Calzadilla et al. (2014).

In the DART-BIO model, we use different land types according to agro-ecological zones (AEZs), based on the GTAP database. AEZs represent 18 types of land, in each region with different crop suitability, productivity potential, and environmental impact. Each of the 18 AEZs is characterized by its particular climate, soil moisture/precipitation, and landform conditions which are basic for the supply of water, energy, nutrients, and physical support to plants. The newest version is available in the GTAP8 database by Baldos and Hertel (2012).

The mobility of land from one land-use type to another is commonly restricted by a nested constant elasticity of transformation (CET) function (see, e.g., Laborde and Valin 2012; Hertel et al. 2010). We choose a three-level nesting, in which land is first allocated between land for agriculture and managed forest. Then, agricultural land is allocated between pasture and crops. In the next level, cropland is allocated between rice, palm, sugar cane/beet and annual crops (wheat, maize, rapeseed, soybeans, other grains, other oilseeds, and other crops). At each level, the elasticity of transformation increases, reflecting that land is more mobile between crops than between forestry and agriculture (see Appendix Table 2). An important difference compared with other approaches (e.g. Laborde and Valin 2012; Bouët et al. 2010) is that we do not differentiate between land prices for growing annual crops. Since farmers can decide year by year which crop to plant, these crops can be easily substituted depending mainly on crop prices. Thus, different annual crops (e.g. wheat and maize) face only one land price entering into their costs. However, paddy rice and perennial crops such as palm fruit and sugar cane are less mobile and therefore face different land prices. Elasticities of transformation between the land uses are the main drivers of land allocation; however, they are very poorly studied in the literature. We currently use numbers from OECD’s PEM model (Abler 2000; Salhofer 2000) which only covers developed countries plus Mexico, Turkey, and South Korea. Therefore, we had to choose values based on certain similarities for several countries (see Appendix Table 2). The effect of differences in land-use modelling is discussed in Calzadilla et al. (forthcoming).

Productivity in the agricultural sector is determined by changes in labour force, the rate of labour productivity growth, and the change in human capital accumulation, as well as the choice of the model structure (e.g. CET nesting) and parameter settings (e.g. elasticity of substitution). Hence, future yield growth is driven by changes in the total productivity factor. A more detailed description of production functions and dynamics is available in Calzadilla et al. (2014).

To simulate the effect of cropland expansion on food security, we set up two scenarios. The baseline scenario represents a continuation of the business as usual economic growth, population growth, and national policies as observed in the DART-BIO 2007 database. In this reference scenario, no expansion of cropland into non-managed land types is assumed.

The assumptions underlying the land expansion (LE) scenario are based on the FAO long-term baseline outlook ‘World agriculture: towards 2030/2050’—The 2012 Revision (Alexandratos and Bruinsma 2012). These reports are the most authoritative sources for forecasts on crop production available. The forecasts are based on annual growth rate projections until 2030/2050 for crop production for selected important food crops.

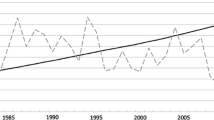

From the information provided in the FAO forecast, we calculate annual growth rates for a linear increase in harvested area from the 2005/2007 base years, as provided by the FAO to 2030 (assumptions on growth rates include the most important crops cultivated on cropland). They enter the DART-BIO model as exogenous parameters. Globally, harvested area is expected to increase by about 7 %, while the regional distribution of land expansion or contraction varies between contraction of cropland (e.g. −11 % in Japan) and expansion of up to 28 % in Paraguay/Argentina/Uruguay/Chile (PAC) (Fig. 1 and Appendix Fig. 5). Accordingly, the land endowment for agricultural production in the DART-BIO model is set to consider these differences. While in northern and middle Europe, China, and India the harvested area shows no significant changes over time, the harvested area in Japan and Russia is reduced. The FAO data (Alexandratos and Bruinsma 2012) show that largest land expansions occur in Latin America (BRA, PAC, LAM) and Rest of Former Soviet Union and Europe (FSU).

Percentage change in global crop production under the land expansion scenario and harvested area in 2030 compared with 2007. Source simulation of production with DART-BIO; harvested area based on Alexandratos and Bruinsma (2012)

Natural potentials for future cropland expansion

The potential for the expansion of cropland is restricted by the availability of land resources and given local natural conditions. Consequently, area that is highly suitable for agriculture according to the prevailing local ecological conditions (climate, soil, terrain) but is not under cultivation today has a high natural potential for being agriculturally used. Policy regulations or socio-economic conditions can further restrict the availability of land for expansion, e.g., by designating protected areas, although they may be suitable for agriculture. Conversely, by applying, e.g., irrigation practices, land can be brought under cultivation, although it may naturally not be suitable. Here, we investigate the potentials for agricultural expansion for near future climate scenario conditions to identify the suitability of non-cropland areas for expansion.

We determine the available energy, water, and nutrient supply for agricultural suitability from climate, soil, and topography data, by applying the global dataset of crop suitability from a fuzzy logic approach by Zabel et al. (2014). It considers 16 economically important staple and energy crops at a spatial resolution of 30 arc seconds. These are barley, cassava, groundnut, maize, millet, oil palm, potato, rapeseed, rice, rye, sorghum, soy, sugarcane, sunflower, summer wheat, and winter wheat. The parameterization of the membership functions that describe each of the crops’ specific natural requirements is taken from Sys et al. (1993). The considered natural conditions are: climate (temperature, precipitation, solar radiation), soil properties (texture, proportion of coarse fragments and gypsum, base saturation, pH content, organic carbon content, salinity, sodicity), and terrain (elevation, slope). The requirements for temperature and precipitation are defined over the growing period. For this case, we calculate the optimal start of the growing period, considering the temporal course of temperature and precipitation and thus the course of dry and rainy seasons.

As a result of the fuzzy logic approach, values in a range between 0 and 1 describe the suitability of a crop for each of the prevailing natural conditions at a certain location. The smallest suitability value over all parameters finally determines the suitability of a crop. The daily climate data (mean daily temperature and precipitation sum) are provided by simulation results from the global climate model ECHAM5 (Jungclaus et al. 2006) for near future (2011–2040) SRES A1B climate scenario conditions. Soil data are taken from the Harmonized World Soil Database (HWSD) (FAO et al. 2012), and topography data are applied from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) (Farr et al. 2007). In order to gather a general crop suitability, which does not refer to one specific crop, the most suitable crop with the highest suitability value is chosen at each pixel. Thus, we create a potential land use for each pixel, based on the most suitable crops. This land use does not refer to actual land use and the actual allocation of crops but is used for the further calculation of natural expansion potential.

In addition to the natural biophysical conditions, we consider today’s irrigated areas based on Siebert et al. (2013). We assume that irrigated areas globally remain constant until 2040, since adequate spatial data on possible future extend of irrigated areas do not exist, although it is likely that freshwater availability for irrigation could be limited in some regions, while in other regions surplus water supply could be used to expand irrigation practices (Elliott et al. 2014). However, it is difficult to project where irrigation practices will evolve, since it is also driven by economic considerations, such as the amount of investment costs that are required to establish irrigation infrastructure.

In principle, all agriculturally suitable land that is not used as cropland today has the natural potential to be converted into cropland. We assume that only urban and built-up areas are not available for conversion, although more than 80 % of global urban areas are agriculturally suitable (Avellan et al. 2012). However, it seems unlikely that urban areas will be cleared at the large scale due to high investment costs, growing cities, and growing demand for settlements. Concepts of urban and vertical farming usually are discussed under the aspects of cultivating fresh vegetables and salads for urban population. They are not designed to extensively grow staple crops such as wheat or maize for feeding the world in the near future. Urban farming would require one-third of the total global urban area to meet only the global vegetable consumption of urban dwellers (Martellozzo et al. 2015). Thus, urban agriculture cannot substantially contribute to global agricultural production of staple crops and consequently is not considered in this study.

Protected areas or dense forested areas are not excluded from the calculation, in order not to lose any information in the further combination with the biodiversity patterns (see chapter 2.3). We use data on current cropland distribution by Ramankutty et al. (2008) and urban and built-up area according to the ESA-CCI land-use/land-cover dataset (ESA 2014). From these data, we calculate the ‘natural expansion potential index’ (I exp) that describes the natural potential for an area to be converted into cropland as follows:

The index is determined by the quality of crop suitability (S) (values between 0 and 1) multiplied with the amount of available area (A av) for conversion (in percentage of pixel area). The available area includes all suitable area that is not cultivated today and not classified as urban or artificial area. The index ranges between 0 and 100 and indicates where the conditions for cropland expansion are more or less favourable, when taking only natural conditions into account, disregarding socio-economic factors, policies, and regulations that drive or inhibit cropland expansion.

Since it is unknown which crop might be used for expansion, the index uses the most suitable crop at each pixel (as given by the general crop suitability) for determining the natural potential for expansion. Consequently, not all crops might be suitable for expansion where I exp is greater than zero. The index is a helpful indicator for identifying areas where natural conditions potentially allow for expansion of cropland in the near future from a biophysical point of view. The index does not allow for determining the likelihood of cropland expansion, since it ignores socio-economic factors and policy regulations because we do not aim to understand the factors that may affect cropland expansion. Rather, our goal is to localize potential conflicting areas.

Trade-offs between biodiversity and potential cropland expansion

As indicators of biodiversity, we use global endemism richness for birds, mammals, and amphibians created from expert-based range maps obtained from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN 2012) and Birdlife databases (BirdLife 2012). Habitat changes due to cropland expansion are the principal driver of extinction risk in these animal groups (Pereira et al. 2012). We choose endemism richness over other biodiversity indicators because it combines species richness with a measure of endemism (i.e. the range sizes of species within an assemblage) and thus indicates the relative importance of a site for global conservation (Kier et al. 2009). We calculate endemism richness as the sum of the inverse global range sizes of all species present in a grid cell. The data are scaled to an equal area grid of 110 × 110 km at the equator (1 arc degree) because at finer spatial resolutions, the underlying species range maps exhibit excessively high false-presence rates, overestimating the area of occupancy of individual species (Hurlbert and Jetz 2007).

Following similar methods as in Kehoe et al. (2015), we overlay endemism richness indicators with the natural expansion potential index to examine the spatial concordance between patterns of global biodiversity and suitability for cropland expansion. First, we statistically quantify the spatially explicit association between endemism richness and cropland expansion potentials using the bivariate version of the local indicator of spatial association (LISA) (Anselin 1995). LISA represents a local version of the correlation coefficient and shows how the nature and strength of the association between two variables vary across a study area. The method allows for the decomposition of global indicators, such as Moran’s I, into the contribution of each individual observation (e.g. a grid cell), while giving an indication of the extent of significant spatial clustering of similar values around that observation. Using OpenGeoDa version 1.2.0 (Anselin et al. 2006), we calculate the local Moran’s I statistic of spatial association for each 110-km grid cell as:

where x i and y j are standardized values of variable x (e.g. cropland expansion potentials) and variable y (e.g. endemism richness) for grid cells i and j, respectively, \(\bar{x}\) and \(\bar{y}\) are the means of the variables, w ij is the spatial weight between cell i and j inversely proportional to Euclidean distance between the two cells, and s 2 is the variance. Based on the values of local Moran’s I, we identify and map spatial associations of (1) high–high values, that is spatial hot spots in which locations with high values of cropland expansion potentials are surrounded by high values of endemism richness, (2) low–low values, that is spatial cold spots in which locations with low values of cropland expansion potentials are surrounded by low values of endemism richness, and (3) high–low and low–high values, where the spatial association between the variables is negative (inverse). The strength of the relationship is measured at the 0.05 level of statistical significance calculated by a Monte Carlo randomization procedure based on 499 permutations (Anselin et al. 2006). We use the resulting areas of high–high values to generate a summary map of high-pressure regions for all three taxonomic groups (birds, mammals, and amphibians). As a second analysis, we delineate the ‘hottest’ hot spots of high cropland expansion potentials and endemism richness by extracting the top 5 and 10 % of the data distribution (Ceballos and Ehrlich 2006). Intersecting these top values of both variables, we create maps of the top pressure regions, where high biodiversity is most threatened by potential cropland expansion.

Results and discussion

The impact of cropland expansion on food security

Food supply and accessibility depend not only on the ability to produce a sufficient quantity and quality of food, but also on the food price level and incomes relative to these prices. We apply the CGE Model DART-BIO in order to compare agricultural production and prices on global and regional scale under two scenarios. The land expansion (LE) scenario (cp. “The DART-BIO model”) is run and compared to results from a baseline scenario without cropland expansion to quantify the price and production changes. To illustrate the effect of expanding cropland on food security, first the changes in global and regional production quantities and trade flows are displayed. Second, changes in price on global and regional scale under the LE scenario are discussed.

Food production and trade flows

Under the LE scenario, global production of primary agricultural goods increases by 3–9 %, while processed food production rises by 3 % compared with the baseline scenario in 2030. A detailed table with price and quantity changes for all crops and processed food sectors is available in Appendix Table 3.

Regionally, the cropland expansion has different impacts on food production. Driven by the amount in cropland expansion/reduction of the scenario, crop production in European countries except Benelux as well as in Russia, Japan, and India is reduced in 2030 compared with 2007 (see Fig. 1). Largest increases in crop production are simulated for Paraguay, Argentina, Uruguay, Chile (PAC) (+34 %), and other regions that face problems in improving food security (Brazil +16 %, LAM +13 %, AFR +11 %, SEA +14 %). Comparing production in 2030 under the LE scenario to the baseline scenario, production of maize, soy beans, and wheat shows largest increase in Latin America. South-East Asia (SEA) and Malaysia/Indonesia (MAI) increase paddy rice production by 11–13 %, while also ‘Rest of Agriculture’ (AGR) rises considerably. Production of, e.g., wheat and AGR in India drops, since expansion potentials are very limited. These results indicate that while food production rises on global average, not all regions produce more under the LE scenario. Thus, their ability to produce a sufficient quality of food is not improved when expanding cropland as under the LE scenario.

Countries are connected via bilateral trade. Different values for cropland expansions result in changing comparative advantages of different regions, which affects trade flows. In 2030, regions in Asia are net importers of most agricultural goods in the baseline scenario. South-East Asia (SEA) reduces its net imports of processed food by more than half under the LE scenario compared with the baseline. At the same time, SEA exports more AGR (+63 %). These exports mainly target India and China, who also increase imports from other regions. Indian’s net imports of crops strongly increase such that private consumption of food in India rises. Regions in Latin America are net exporters of crops and net importers of processed food under the baseline scenario in 2030. Under the LE scenario, net exports of crops increase compared with the baseline, while less processed food is imported. This indicates that cropland expansion, though distributed differently in different regions, provides more food to consumers in all regions compared with the baseline run.

Food prices

Agricultural prices are also important for food security, particularly for net importing countries, and people who do not produce food themselves. Comparing results of the LE scenario with the baseline, global average prices of crops fall by 6–20 % (see Table 3 in Appendix). The highest price decreases are simulated for soy beans, since they are produced in regions with the highest cropland expansions. In addition, by 2030 the demand for soy beans is larger compared with, e.g., paddy rice as soy beans are used as feedstuff to satisfy rising meat consumption over time, and biofuel quotas. As a result, soybean areas expand by 13 % compared with the baseline run. The area expansion for paddy rice amounts to 5 %, which results in a global average price decrease of 6 %.

Driven by the scenario assumptions, regional production costs, and trade flows, regional price changes vary considerably. Taking wheat as an example, strongest price decreases are simulated for Brazil and PAC, where most of the cropland expansion takes place (see Table 1). But also regions in which cropland does not expand or only to a limited degree profit from decreasing crop prices. While, e.g., wheat production in India decreases under the LE scenario compared with the baseline in 2030, wheat prices drop by 5 % since India benefits from low wheat prices on the world market (−11 %) (see Table 1).

In summary, our results indicate that cropland expansion improves food security, particularly in those regions that currently face problems in providing sufficient and affordable quantities of food to people. However, data from FAO used in the LE scenario provide no spatial information on the locations within the regions where expansion takes place. Accordingly, no statement on substituted land cover and possible loss of biodiversity is possible. Therefore, in the following section, potential areas for cropland expansion are identified.

Identification of natural potentials for cropland expansion

Assuming that cropland expansion is potentially possible where the quality of land is suitable for the cultivation of crops and area is still available for the conversion of land into cropland, Fig. 2 shows the calculated index of the natural expansion potential. The greater the agricultural suitability and the larger the available area for expansion, the greater the value of the index. Red coloured areas in Fig. 2 indicate high natural potential for cropland expansion.

Index of natural potentials for the expansion of cropland. The index is calculated as the result of agricultural suitability under SRES A1B climate scenario conditions for 2011–2040 and the availability of suitable land for expansion. The index ranges from 1 (low potential for expansion, green) to 100 (high potential for expansion, red). Values with 0 (no potential for expansion) are masked out. Map in Eckert IV projection, 30-arc-second spatial resolution

We identify high natural expansion potentials in African countries (e.g. Cameroon, Chad, Gabon, Sudan, western parts of Ethiopia, and Tanzania), Central and South America (Mexico, Nicaragua, Uruguay, and parts of Argentina), fragmented parts of Asia (north-eastern part of China, northern parts of Australia and Papua New Guinea) and small parts of Russia. These areas are characterized by fertile soils and adequate climate conditions for at least one of the investigated crops, while at the same time these areas are not under cultivation today according to the applied data. The high expansion potential in parts of tropical countries, such as Cameroon, Gabon, Nicaragua, Indonesia, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, and the Philippines, is mainly caused by the high crop suitability of oil palm in these regions, while other crops are not suitable here (Zabel et al. 2014). Regions with high natural expansion potential in the Sahel Zone mainly owe their high values to the good suitability of sorghum.

Certainly, many of the named regions with high natural potential for expansion are in the focus of cropland expansion and land grabbing already today. While the inner tropical basins of Brazil and the Congo show large areas for possible expansion, the value for the expansion potential index is relatively low here, since the agricultural suitability is inhibited due to marginal soil quality conditions. On the other hand, the potential for expansion is relatively low in North America and Europe, where most of the suitable areas are already under cultivation today. Therefore, the potential for further expansion is relatively low. Topography also affects agricultural suitability, and thus, the natural potential for expansion depends also on the extent of suitable valleys within mountainous areas.

Increasing mean temperatures due to climate change until 2040 are considered in the calculation of natural expansion potentials. Climate change, e.g., affects the northern hemisphere, where the climatic frontier for cultivation shifts northwards with time such that additional land potentially becomes suitable and thus is available for expansion. On the other hand, suitability decreases for most of the 16 investigated crops due to climate change, especially for cereals in the tropics and the Mediterranean.

Spatial patterns of potential cropland expansion and biodiversity

The LISA analyses reveal regionally variable spatial concordance between patterns of cropland expansion potentials and global biodiversity (Fig. 3). Regions with low potential of cropland expansion and low biodiversity (i.e. spatial cold spots) are similar across all three taxonomic groups, covering mostly non-arable, desert, or ice-covered land (39 % of terrestrial ecosystems; Fig. 3a–c). The hot spots, i.e. regions where high biodiversity is potentially threatened by cropland expansion, vary more substantially among the considered vertebrate groups but all are focused primarily in the tropics, covering 18 % of the terrestrial land surface. While the hot spot patterns for birds and mammals show high spatial congruence (67 % overlap), the areas of high expansion potentials associated with high endemism richness are relatively smaller for amphibians (41 % overlap with the other taxa) due to the generally smaller ranges of amphibian species concentrated in specific geographical areas. However, the summary of statistically significant hot spots for all three taxonomic groups shows a spatially consistent pattern of high-pressure regions (Fig. 3d), covering Central and South America, Central Africa and Madagascar, Eastern Australia, and large portions of Southeast Asia. Other regions with higher suitability for cropland expansion either are not significantly associated with endemism richness or occur in areas with relatively low levels of endemism richness (11 % of the terrestrial land surface), e.g. the Midwest of North America, Eastern Europe, or parts of sub-Saharan Africa.

Local indicator of spatial association (LISA) between cropland expansion potentials and endemism richness for birds (a), mammals (b), and amphibians (c). The pattern shows how the nature and strength of the association between two variables vary across the globe. High–high clusters show hot spot locations, in which high cropland expansion potentials are associated with high values of endemism richness. Low–low clusters show cold spot locations, in which low cropland expansion potentials are associated with low values of endemism richness. High–low and low–high clusters show inverse spatial association. The map in (d) summarizes all high–high associations to show high-pressure regions for one, two, or all three taxonomic groups. Maps in Eckert IV projection, 1-arc-degree spatial resolution

The spatial intersect of the top 5 and 10 % of data on cropland expansion and biodiversity (Fig. 4) further pinpoints the top pressure regions, where high levels of endemism richness for all considered taxa may be most threatened by potential cropland expansion (3 % overlap for top 5 % data and 13 % overlap for top 10 % data). These ‘hottest’ hot spots of potential future conflict between biodiversity and agriculture are found in Central America and the Caribbean, in the tropical Andes and south-western Brazil, in West and East Africa, including Madagascar, and in several parts of tropical Asia, in particular the Indochina region, the Indonesian islands, and Papua New Guinea.

Overlay of top 5 % (a) and top 10 % (b) of natural cropland expansion potentials and global endemism richness for three vertebrate taxa (birds, mammals, and amphibians). The intersect of both datasets (in red) highlights the top pressure regions, where high biodiversity (i.e. high numbers of range size equivalents) may be particularly threatened by potential cropland expansion. Maps in Eckert IV projection, 1-arc-degree spatial resolution

Although our results highlight relatively large areas of potential future pressure on biodiversity, it does not mean that all types of habitats in each 110-km grid cell would be equally affected if cropland expansion occurred. When using endemism richness as an indicator of biodiversity, our concern is not the area of habitat but the number of range equivalents, i.e. fractions of species global ranges that are contained within a grid (Kier et al. 2009). For example, many mountainous regions in the tropics identified as high-pressure regions have high endemism richness due to many different species inhabiting zones along topographical and climate gradients. Presumably, the habitats in higher elevations are less likely to be affected than habitats located in lower regions because of differences in soil characteristics, slope steepness, accessibility, and other fine-scale factors restricting agricultural suitability and thus natural expansion potential in mountainous areas.

On the other hand, we also identify areas where high suitability for additional expansion of food production may pose lower threats to conservation of biodiversity. These regions, such as Eastern Europe, sub-Saharan Africa, or Northeast China, coincide with the ‘extensive cropping land system’ (Václavík et al. 2013) that represents relatively easily achievable opportunity for an expansion or intensification of agricultural production, especially for wheat, maize, or rice. Here, large production gains could be achieved if yields were increased to only 50 % of attainable yields (Mueller et al. 2012). However, even areas with relatively low endemism richness may still harbour valuable species or include cultural heritage that cropland expansion may threaten. Our analysis identifies where the high- and low-pressure regions are located but does not explain how the various aspects of biodiversity would be threatened by future land-use changes. Therefore, we caution that more detailed and context-specific assessments are needed to understand the possible outcomes of different expansion strategies. In addition to biodiversity and economic indicators, these assessments should consider other (non-provisioning) ecosystem services, resilience of land-use systems, and cultural and societal outcomes of increasing food production (Kehoe et al. 2015).

Summary and conclusions

Trade-offs between food security and biodiversity are driven by various interdependent socio-economic and biophysical parameters that operate at both global and local scales. In this study, we account for these parameters by combining three methodological approaches to analyse the effects of expanding agricultural production: (1) we run an economic scenario analysis with a computable general equilibrium model to examine the effect of an exogenous cropland land expansion on changes in crop production and prices, (2) we determine where an expansion of cropland would be possible under the given natural conditions, and (3) we statistically analyse where the natural potential for cropland expansion may threaten biodiversity.

We show that there are potential trade-offs between increased food production and protection of biodiversity. On the one hand, allowing the expansion of cropland generally results in improved food security in terms of decreased food prices and increased quantity, not only in those regions where crop production rises, but also in net importing countries such as India and China. On the other hand, the results show that estimated cropland expansion could take place in many regions that are valuable for biodiversity conservation. From an economic point of view, the highest expected expansion of cropland according to FAO takes place in South America, particularly in Argentina, Bolivia, and Uruguay. Considering that these countries also have a high biophysical potential for cropland expansion as well as relatively high endemism richness, they represent valuable regions from the conservation point of view but with the highest pressure for land clearing. Similar conclusions can be made for regions in Australia, Brazil, and Africa. Our analyses highlight such regions that deserve further attention and more detailed and context-specific assessments to understand the possible outcomes of different food security strategies, while at the same time establishing mechanisms to efficiently protect habitats with high biodiversity.

Our results are relevant with respect to the SDGs for implementing and enforcing sustainable pathways for increasing agricultural production, ensuring food security while conserving biodiversity and ecosystem services. A report by the International Council for Science (ICSU) and the International Social Science Council (ISSC) states that some goals may conflict. The presented approach contributes to identifying the key trade-offs and complementarities among goals and targets, as required in SDGs. In addition, our study contributes to the land sharing versus sparing debate that generated a controversial discussion on the pressing problems of feeding a growing human population and conserving biodiversity (Fischer et al. 2008; Godfray 2011; Phalan et al. 2011; von Wehrden et al. 2014). Our approach represents one of the first examples of moving forward from the bipolar framework (Fischer et al. 2014). We advance the framework by (1) accounting for economic parameters, thus focusing on food security rather than mere production, (2) treating agricultural landscapes as complex social–ecological systems, (3) accounting for biophysical and socio-economic factors that operate at different spatial scales, and (4) defining biodiversity with a metric that combines species richness with conservation value of the area.

References

Abler DG (2000) Elasticities of substitution and factor supply in Canadian, Mexican and US agriculture. Report to the Policy Evaluation Matrix (PEM) Project Group, OECD, Paris

Alexandratos N, Bruinsma J (2012) World agriculture towards 2030/2050: the 2012 revision. ESA Working paper No. 12-03. FAO, Rome

Anselin L (1995) Local Indicators of Spatial Association—Lisa. Geogr Anal 27:93–115. doi:10.1111/j.1538-4632.1995.tb00338.x

Anselin L, Syabri I, Kho Y (2006) GeoDa: an introduction to spatial data analysis. Geogr Anal 38:5–22. doi:10.1111/j.0016-7363.2005.00671.x

Avellan T, Meier J, Mauser W (2012) Are urban areas endangering the availability of rainfed crop suitable land? Remote Sens Lett 3:631–638. doi:10.1080/01431161.2012.659353

Baldos ULC, Hertel TW (2012) Development of a GTAP 8 land use and land cover data base for years 2004 and 2007. GTAP Research Memorandum No. 23, September 2012. https://www.gtap.agecon.purdue.edu/resources/res_display.asp?RecordID=3967. Accessed 15 Sept 2015

BirdLife (2012) BirdLife data zone. http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/home. Accessed 6 Feb 2014

Bouët A, Dimaranan BV, Valin H (2010) Modeling the global trade and environmental impacts of biofuel policies. IFPRI Discussion Paper (01018), International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington

Bruinsma J (2011) The resources outlook: By how much do land, water and crop yields need to increase by 2050?. FAO, Rome

Calzadilla A, Delzeit R, Klepper G (2014) DART-BIO: Modelling the interplay of food, feed and fuels in a global CGE model. Kiel Working Paper No. 1896. Kiel Institute for the World Economy, Kiel, Germany. https://www.ifw-members.ifw-kiel.de/publications/dart-bio-modelling-the-interplay-of-food-feed-and-fuels-in-a-global-cge-model/KWP1896.pdf. Accessed 16 Sept 2015

Calzadilla A, Delzeit R, Klepper G (forthcoming) Analysing the effect of the recent EU-biofuels proposal on global agricultural markets. In: Bryant T (ed) The WSPC reference set on natural resources and environmental policy in the era of global change

Ceballos G, Ehrlich PR (2006) Global mammal distributions, biodiversity hotspots, and conservation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:19374–19379. doi:10.1073/pnas.0609334103

Corvalan C, Hales S, McMichael AJ (2005) Ecosystems and human well-being: health synthesis: a report of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. WHO, Geneva

Elliott J, Deryng D, Müller C, Frieler K, Konzmann M, Gerten D, Glotter M, Flörke M, Wada Y, Best N (2014) Constraints and potentials of future irrigation water availability on agricultural production under climate change. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:3239–3244. doi:10.1073/pnas.1222474110

ESA (2014) Land Cover CCI, Product User Guide, Version 2

FAO, IIASA, ISRIC, ISSCAS, JRC (2012) Harmonized world soil database (version 1.2). FAO and IIASA, Rome and Laxenburg

FAO, Ifad, WFP (2014) The state of food insecurity in the world 2014. strengthening the enabling environment for food security and nutrition. FAO, Rome

FAOSTAT (2015) FAOSTAT land USE module. Retrieved 22 Mai 2015. http://faostat.fao.org/site/377/DesktopDefault.aspx?PageID=377#ancor. Accessed 31 May 2015

Farr TG, Rosen PA, Caro E, Crippen R, Duren R, Hensley S, Kobrick M, Paller M, Rodriguez E, Roth L (2007) The shuttle radar topography mission. Rev Geophys. doi:10.1029/2005RG000183

Fischer J, Brosi B, Daily GC, Ehrlich PR, Goldman R, Goldstein J, Lindenmayer DB, Manning AD, Mooney HA, Pejchar L (2008) Should agricultural policies encourage land sparing or wildlife-friendly farming? Front Ecol Environ 6:382–387. doi:10.1890/070019

Fischer J, Abson DJ, Butsic V, Chappell MJ, Ekroos J, Hanspach J, Kuemmerle T, Smith HG, Wehrden H (2014) Land sparing versus land sharing: moving forward. Conserv Lett 7:149–157. doi:10.1111/conl.12084

Flynn DF, Gogol-Prokurat M, Nogeire T, Molinari N, Richers BT, Lin BB, Simpson N, Mayfield MM, DeClerck F (2009) Loss of functional diversity under land use intensification across multiple taxa. Ecol Lett 12:22–33. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01255.x

Foley JA, DeFries R, Asner GP, Barford C, Bonan G, Carpenter SR, Chapin FS, Coe MT, Daily GC, Gibbs HK, Helkowski JH, Holloway T, Howard EA, Kucharik CJ, Monfreda C, Patz JA, Prentice IC, Ramankutty N, Snyder PK (2005) Global consequences of land use. Science 309:570–574. doi:10.1126/science.1111772

Foley JA, Ramankutty N, Brauman KA, Cassidy ES, Gerber JS, Johnston M, Mueller ND, O’Connell C, Ray DK, West PC, Balzer C, Bennett EM, Carpenter SR, Hill J, Monfreda C, Polasky S, Rockstrom J, Sheehan J, Siebert S, Tilman D, Zaks DPM (2011) Solutions for a cultivated planet. Nature 478:337–342. doi:10.1038/nature10452

Garnett T, Appleby M, Balmford A, Bateman I, Benton T, Bloomer P, Burlingame B, Dawkins M, Dolan L, Fraser D (2013) Sustainable intensification in agriculture: premises and policies. Science 341:33–34. doi:10.1126/science.1234485

Godfray HCJ (2011) Food and Biodivers. Science 333:1231–1232. doi:10.1126/science.1211815

Godfray HCJ, Beddington JR, Crute IR, Haddad L, Lawrence D, Muir JF, Pretty J, Robinson S, Thomas SM, Toulmin C (2010) Food security: the challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science 327:812–818. doi:10.1126/science.1185383

Gregory PJ, George TS (2011) Feeding nine billion: the challenge to sustainable crop production. J Exp Bot. doi:10.1093/jxb/err232

Gustavsson J, Cederberg C, Sonesson U, van Otterdijk R, Meybeck A (2011) Global food losses and food waste. FAO, Rome

Hertel T, Golub A, Jones A, OHare M, Plevin R, Kammen D (2010) Effects of US maize ethanol on global land use and greenhouse gas emissions: estimating market-mediated responses. Bioscience 60:223–231. doi:10.1525/bio.2010.60.3.8

Hosonuma N, Herold M, De Sy V, DeFries RS, Brockhaus M, Verchot L, Angelsen A, Romijn E (2012) An assessment of deforestation and forest degradation drivers in developing countries. Environ Res Lett 7:044009. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/7/4/044009

Hurlbert AH, Jetz W (2007) Species richness, hotspots, and the scale dependence of range maps in ecology and conservation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:13384–13389. doi:10.1073/pnas.0704469104

IIASA, FAO (2012) Global agro-ecological Zones (GAEZ v3.0)—model documentation. IIASA, FAO, IIASA, Laxenburg, Austria and FAO, Rome, Italy

IUCN (2012) The IUCN red list of threatened species. http://www.iucnredlist.org/technical-documents/spatial-data. Accessed 6 Feb 2014

Jungclaus J, Keenlyside N, Botzet M, Haak H, Luo J-J, Latif M, Marotzke J, Mikolajewicz U, Roeckner E (2006) Ocean circulation and tropical variability in the coupled model ECHAM5/MPI-OM. J Clim 19:3952–3972. doi:10.1175/JCLI3827.1

Kastner T, Rivas MJI, Koch W, Nonhebel S (2012) Global changes in diets and the consequences for land requirements for food. P Natl Acad Sci USA 109:6868–6872. doi:10.1073/pnas.1117054109

Kehoe L, Kuemmerle T, Meyer C, Levers C, Václavík T, Kreft H (2015) Global patterns of agricultural land-use intensity and biodiversity. Divers Distrib 21:1308–1318. doi:10.1111/ddi.12359

Kier G, Kreft H, Lee TM, Jetz W, Ibisch PL, Nowicki C, Mutke J, Barthlott W (2009) A global assessment of endemism and species richness across island and mainland regions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:9322–9327. doi:10.1073/pnas.0810306106

Klepper G, Peterson S (2006a) Emissions trading, CDM, JI and more—the climate strategy of the EU. Energy J 27:1–26. doi:10.2139/ssrn.703881

Klepper G, Peterson S (2006b) Marginal abatement cost curves in general equilibrium: the influence of world energy prices. Resour Energy Econ 28:1–23. doi:10.2139/ssrn.615665

Kretschmer B, Narita D, Peterson S (2009) The economic effects of the EU biofuel target. Energy Econ 31:285–294. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2009.07.008

Laborde D, Valin H (2012) Modelling land use changes in a global CGE: assessing the EU biofuel mandates with the MIRAGE-BioF model. Clim Change Econ 3:1250017. doi:10.1142/S2010007812500170

Martellozzo F, Landry J-S, Plouffe D, Seufert V, Rowhani P, Ramankutty N (2015) Urban agriculture and food security: a critique based on an assessment of urban land constraints. Glob Food Secur 4:8. doi:10.1016/j.gfs.2014.10.003

Mauser W, Klepper G, Zabel F, Delzeit R, Hank T, Putzenlechner B, Calzadilla A (2015) Global biomass production potentials exceed expected future demand without the need for cropland expansion. Nat Commun. doi:10.1038/ncomms9946

Mueller ND, Gerber JS, Johnston M, Ray DK, Ramankutty N, Foley JA (2012) Closing yield gaps through nutrient and water management. Nature 490:254–257. doi:10.1038/nature11420

Narayanan G, Badri AA, McDougall R (eds) (2012) Global Trade, Assistance, and Production: The GTAP 8 Data Base, Center for Global Trade Analysis. Purdue University, West Lafayette

Newbold T, Hudson LN, Hill SL, Contu S, Lysenko I, Senior RA, Börger L, Bennett DJ, Choimes A, Collen B (2015) Global effects of land use on local terrestrial biodiversity. Nature 520:45–50. doi:10.1038/nature14324

Pereira HM, Navarro LM, Martins IS (2012) Global biodiversity change: the bad, the good, and the unknown. Annu Rev Environ Resour 37:25–50. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-042911-093511

Phalan B, Onial M, Balmford A, Green RE (2011) Reconciling food production and biodiversity conservation: land sharing and land sparing compared. Science 333:1289–1291. doi:10.1126/science.1208742

Ramankutty N, Evan AT, Monfreda C, Foley JA (2008) Farming the planet: 1. Geographic distribution of global agricultural lands in the year 2000. Glob Biogeochem Cycles 22:GB1003. doi:10.1029/2007GB002952

Ray DK, Foley JA (2013) Increasing global crop harvest frequency: recent trends and future directions. Environ Res Lett 8:044041. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/8/4/044041

Ray DK, Mueller ND, West PC, Foley JA (2013) Yield trends are insufficient to double global crop production by 2050. PLoS ONE 8:e66428. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0066428

Rosenzweig C, Elliott J, Deryng D, Ruane AC, Müller C, Arneth A, Boote KJ, Folberth C, Glotter M, Khabarov N (2013) Assessing agricultural risks of climate change in the 21st century in a global gridded crop model intercomparison. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:3268–3273. doi:10.1073/pnas.1222463110

Salhofer K (2000) Elasticities of substitution and factor supply elasticities in european agriculture: a review of past studies. Diskussionspapier Nr. 83-W-2000. Institut für Wirtschaft, Politik und Recht, Universität für Bodenkultur, Wien

Siebert S, Henrich V, Frenken K, Burke J (2013) Global map of irrigation areas version 5. Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-University, Bonn, Germany/Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy

Springer K (1998): The DART general equilibrium model: a technical description. Kiel Working Paper No. 883. Kiel Institute for the World Economy, Kiel, Germany. https://www.ifw-kiel.de/forschung/Daten/dart/kap883.pdf. Accessed 16 Sept 2015

Sys CO, van Ranst E, Debaveye J, Beernaert F (1993) Land evaluation: part III crop requirements, vol 1–3. G.A.D.C., Brussels

Tilman D (1999) Global environmental impacts of agricultural expansion: the need for sustainable and efficient practices. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:5995–6000. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.11.5995

Tilman D, Balzer C, Hill J, Befort BL (2011) Global food demand and the sustainable intensification of agriculture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:20260–20264. doi:10.1073/pnas.1116437108

United Nations (2014) The Millenium Development Goals Report 2014. United Nations, New York

Václavík T, Lautenbach S, Kuemmerle T, Seppelt R (2013) Mapping global land system archetypes. Global Environ Chang 23:1637–1647. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.09.004

van Ittersum MK, Cassman KG, Grassini P, Wolf J, Tittonell P, Hochman Z (2013) Yield gap analysis with local to global relevance—a review. Field Crops Res 143:4–17. doi:10.1016/j.fcr.2012.09.009

von Wehrden H, Abson DJ, Beckmann M, Cord AF, Klotz S, Seppelt R (2014) Realigning the land-sharing/land-sparing debate to match conservation needs: considering diversity scales and land-use history. Landsc Ecol 29:941–948. doi:10.1007/s10980-014-0038-7

Weitzel M, Hübler M, Peterson S (2012) Fair, optimal or detrimental? Environmental vs. strategic use of carbon-based border measures. Energy Econ 34:198–207. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2012.08.023

West PC, Gerber JS, Engstrom PM, Mueller ND, Brauman KA, Carlson KM, Cassidy ES, Johnston M, MacDonald GK, Ray DK, Siebert S (2014) Leverage points for improving global food security and the environment. Science 345:325–328. doi:10.1126/science.1246067

Zabel F, Putzenlechner B, Mauser W (2014) Global agricultural land resources—a high resolution suitability evaluation and its perspectives until 2100 under climate change conditions. PLoS ONE 9:e107522. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0107522

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Holger Kreft for assistance with biodiversity datasets. This project was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Grant 01LL0901A: Global Assessment of Land Use Dynamics, Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Ecosystem Services—GLUES). CM acknowledges support by sDiv, the Synthesis Centre of the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) Halle-Jena-Leipzig (DFG FZT 118).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10113-016-0944-0.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Delzeit, R., Zabel, F., Meyer, C. et al. Addressing future trade-offs between biodiversity and cropland expansion to improve food security. Reg Environ Change 17, 1429–1441 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-016-0927-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-016-0927-1