Abstract

Previous research has shown that the production of Arabica coffee (Coffea arabica), the main source of high-quality coffee, will be severely affected by climate change. Since large numbers of smallholder farmers in tropical mountain regions depend on this crop as their main source of income, the repercussions on farmer livelihoods could be substantial. Past studies of the issue have largely focused on Latin America, while the vulnerability of Southeast Asian coffee farmers to climate change has received very little attention. We present results of a modeling study of climate change impacts on Arabica coffee in Indonesia, one of the world’s largest coffee producers. Focusing on the country’s main Arabica production zones in Sumatra, Sulawesi, Flores, Bali and Java, we show that there are currently extensive areas with a suitable climate for Arabica coffee production outside the present production zones. Temperature increases are likely to combine with decreasing rainfall on some islands and increasing rainfall on others. These changes are projected to drastically reduce the total area of climatically suitable coffee-producing land across Indonesia by 2050. However, even then there will remain more land area with a suitable climate and topography for coffee cultivation outside protected areas available than is being used for coffee production now, although much of this area will not be in the same locations. This suggests that local production decline could at least partly be compensated by expansion into other areas. This may allow the country to maintain current production levels while those of other major producer countries decline. However, this forced adaptation process could become a major driver of deforestation in the highlands. We highlight the need for public and private policies to encourage the expansion of coffee farms into areas that will remain suitable over the medium term, that are not under legal protection, and that are already deforested so that coffee farming could make a positive contribution to landscape restoration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It has been well documented that agricultural production globally will be greatly affected by climate change (Brown and Funk 2008; Lobell et al. 2008; Vermeulen et al. 2012). This is especially the case where climates become drier and less predictable, extreme weather events more frequent and intense, and where temperatures exceed the optimum for crop growth and development (Hannah et al. 2013). Where crops are negatively affected, farmers may have to change management practices and varieties, diversify into alternative crops or livestock (Thornton et al. 2009; Schroth and Ruf 2014), or leave agriculture altogether. Countries may become less food secure and lose income from the export of agricultural commodities. On the other hand, countries may at least temporarily benefit from climate change if they are located in cold climates due to latitude or altitude, or are located in an area of increasing rainfall. Especially in large countries that harbor a range of climatic conditions, positive and negative effects on crops may also to some extent balance each other out at a national level.

In addition to direct climate effects on agricultural production, indirect effects may occur as climate change differentially affects countries that compete with each other in global commodity markets. For example, a negative effect of climate change on cocoa production in West Africa (Läderach et al. 2013) might create new market opportunities for cocoa producers in Brazil, and a decline of quality coffee production in Mesoamerica (Schroth et al. 2009; Baca et al. 2014; Rahn et al. 2014) might widen the market niche for coffee producers in East Africa or parts of Asia that are less severely hit by climate change.

Here, we look at the case of Arabica coffee production in Indonesia, one of the world’s largest coffee producers with annual production averaging 534,000 t between 2005 and 2012 (ICO 2014) of which an estimated 93,000 t is Arabica coffee (http://gain.fas.usda.gov/). In Latin America, some traditional coffee-producing countries may see the quantity and quality of their coffee output drastically decrease during the coming decades because of higher temperatures, lower and less regular rainfall, increased risks of extreme weather events (Schroth et al. 2009; Tucker et al. 2010), and altered pest and disease pressures (Jaramillo et al. 2009). Indonesia, on the other hand, has several major coffee-growing regions spread over a number of its larger and smaller islands and, therefore, offers a wider range of climatic conditions. Moreover, due to its size and mountainous landscape, it boasts significant areas at altitudes above 1,000 or 1,200 m that could be suitable for Arabica coffee production provided that soil and topographic conditions are acceptable (Specialty Coffee Association of Indonesia, http://www.sca-indo.org/). Could Indonesia thus emerge as an important producer in the global Arabica coffee market by taking advantage of its vast mountain landscapes to maintain or even increase production as climate change progressively forces other countries out of the market?

We combine a climate model calibrated on the conditions of Indonesia’s major Arabica coffee production zones with climate change projections from Global Circulation Models to predict changes in climatic suitability in current coffee production zones as well as areas not currently used for coffee. We identify areas that will remain or become suitable for Arabica coffee production as the climatic suitability of current production zones declines. We also show where areas of current and future climatic suitability for coffee expansion overlap with legally protected areas that may come under increasing pressure from coffee farmers, including farmers who may be displaced by climate change from their current coffee farms.

Materials and methods

Prediction of current climatic suitability for coffee

In the mountain environments where Arabica coffee is mostly grown, climatic conditions can vary over relatively small distances. Therefore, climate change can lead to significant local variations in relative climatic suitability (Schroth et al. 2009). We used maximum entropy (Maxent), a general-purpose model for making predictions or inferences from incomplete information (Phillips et al. 2006), to estimate the spatial distribution of climatic conditions that are suitable for growing Arabica coffee throughout the Indonesian islands. The specific climatic conditions found within current Indonesian coffee production zones were used for model calibration. A similar approach has previously been used for modeling the impacts of climate change on Arabica coffee in the highlands of Mexico (Schroth et al. 2009), Central America (Rahn et al. 2014) and East Africa (Läderach and van Asten 2012). With some modifications, it has also been used for predicting the impacts of climate change on other tree crops (Läderach et al. 2013).

The locations of major current Arabica coffee production zones in Indonesia (Aceh, North Sumatra, Sulawesi, Flores, Bali and East Java) were obtained from a recent development project (Amarta) in cooperation with the Specialty Coffee Association of Indonesia that attempted to map the major coffee origins in the country using farmer interviews and ground verification. The maps were not sufficiently detailed to exclude locally unsuitable areas for coffee such as deep valleys and high mountain peaks. Thus, these polygons were further narrowed by restricting them to the altitudinal belt of main coffee production in each production zone. This altitudinal belt, assumed to represent the typical climates for coffee production, was identified for each of the six zones based on observations made by one of the contributing authors over 15 years of field research in Indonesia (Table S1).

For calibrating the climate model, 5,600 points were generated systematically covering the six coffee production polygons with a 0.5 arcmin grid. In addition, a random background sample at a 5:1 ratio of background to calibration points was drawn from outside the coffee production zones to characterize the general environment. Background sampling at this ratio is within the range supported by the literature (Lobo and Tognelli 2011; Barbet-Massin et al. 2012) and resulted in the most accurate predicted distributions. The climatic conditions at the calibration points of known occurrence and random pseudo-absence of Arabica coffee were used to train the Maxent algorithm. The derived models were applied to climate surfaces to estimate the relative climatic suitability for Arabica coffee. Spatial climate data were obtained from the WorldClim database (Hijmans et al. 2005, www.worldclim.org). WorldClim data have been generated at a 30 arc-s spatial resolution (1 km) through an interpolation algorithm using long-term average monthly climate data from weather stations. Hijmans et al. (2005) used data from stations for which there were long-standing records, calculating means of the 1960–1990 period and including only weather stations with more than 10 years of data. The data on which WorldClim is based in Indonesia come from 729 stations with precipitation data (of which 49 are at 1,000 m altitude or higher), 108 stations with mean temperature data (9 at 1,000 m or higher) and 144 stations with minimum and maximum temperatures (6 at 1,000 m or higher). The maximum altitude for all variables is 3,023 m. Our model used the 19 bioclimatic variables (Table S2) provided by WorldClim that are derived from these monthly temperature and rainfall values. These variables are often used in ecological niche modeling. They represent annual trends (such as mean annual temperature and annual precipitation), seasonality (such as annual range in temperature and precipitation), and extreme or limiting environmental factors (such as temperature of the coldest and warmest months, and precipitation of the wettest and driest quarters).

From the spatial distribution of the 19 bioclimatic variables, Maxent generates a map of probabilities whether the climate at a location is similar to present locations. In this case, it presents the climates where Arabica coffee is currently grown in Indonesia. An area was considered suitable for growing Arabica coffee if the suitability calculated by Maxent was >35 % and unsuitable if it was less. This threshold was determined by the maximum sum of sensitivity and specificity criterion as suggested by Liu et al. (2013). According to visual inspection, the limits of the thus determined suitable areas showed good coincidence with the limits of the coffee production zones on the Amarta coffee maps (Fig. S1).

From the areas identified as climatically suitable for coffee farming, all land with over 25° slope was excluded as being too steep, which corresponds to the limit of cultivable land according to Sheng (1989). This value is conservative since tree crops can be (and often are) grown on steeper slopes if soil conservation measures are applied (Sheng 1989) but takes into account that soils on steeper slopes may be too shallow for coffee. Legally protected areas (existing or proposed) according to the World Database on Protected Areas (UNEP-WCMC 2012) were also excluded from the suitable area. Furthermore, we excluded protection forests (hutan lindung) and other national protection categories, for which recent spatial information was provided by the Indonesian Ministry of Forestry. While it is acknowledged that coffee is sometimes cultivated within protection forests across Indonesia (Arifin et al. 2008), as a general rule, protection forests have been designated as a cultivation-free forest area for maintaining watershed integrity.

Projection of future climatic suitability

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fourth Assessment Report in 2007 is based on the results of 21 global climate models (GCMs; www.ipcc-data.org.ch). The spatial resolution of the GCM results is, however, very coarse. Therefore, we used statistically downscaled data derived from 19 GCMs (Table S3) to produce 1 km resolution surfaces of the mean monthly maximum and minimum temperatures and monthly precipitation. In all cases, we used the IPCC scenario SRES-A2a (“business as usual”).

For the downscaling, the centroid of each GCM grid cell was calculated and the anomaly in climate was assigned to that point. The statistical downscaling was then applied by interpolating between the points to the desired resolution using the same spline interpolation method used to produce the WorldClim dataset for current climates (Ramirez-Villegas and Jarvis 2010). The anomaly for the higher resolution was then added to the current distribution of climate (derived from WorldClim) to produce a surface of future climate. This method assumes that the current meso-distribution of climate characteristics will remain the same, but that regionally there will be a change in the baseline (Hijmans et al. 2005).

Validation and uncertainty of the model

Using the evidence points, five Maxent training cycles were performed, each time using a different set of 80 % of the points for model training and the remaining 20 % for model testing. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) was used as a measure of model skill (Peterson et al. 2008). Performance of the Maxent model was generally high, with AUC values above 0.999 on the test data. Remaining uncertainties are mostly caused by model parameters (that is, a slightly different Maxent regression model is generally obtained for each of the replicates) and by the locations of input evidence data (Fig. S2). Using the five model runs, baseline and future distributions were projected onto the 30 arc-s grids of WorldClim and the 19 downscaled GCMs, respectively. For each time step, the model average was calculated. For future conditions, the coefficient of variation across GCM outputs was calculated to illustrate the model uncertainty for suitable areas.

Results

Present climatic suitability for Arabica coffee

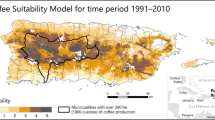

Our model estimated that the total climatically and topographically suitable area for Arabica coffee production within the current production zones of Aceh, North Sumatra, Sulawesi, Flores, Bali and East Java is about 360,000 ha (Table 1). By far, the largest suitable area, with over 210,000 ha, was in the current coffee production zone of North Sumatra (Fig. 1). This was followed by Aceh and Sulawesi (Fig. 1), with smaller areas in Flores, Bali and finally East Java (Fig. 2; Table 1).

Outside the current coffee production zones, the model identified a further 324,000 ha as climatically and topographically suitable for coffee production, but not currently being used as such (Table 1). Much of this area was located in North Sumatra and Aceh, followed in importance by Sulawesi (Fig. 1), Flores and then Bali and East Java (Fig. 2). The total suitable area for Arabica coffee farming according to the model was thus about 684,000 ha.

Future climatic suitability for Arabica coffee

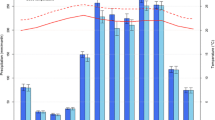

The climate of the Indonesian islands, and with it the size and location of areas with a suitable climate for Arabica coffee production, is projected to change significantly over the next few decades. Table 2 shows mean annual rainfall and temperature and their respective ranges within the current Arabica coffee production zones, as well as their projected changes by 2050. While average temperatures are projected to increase by about 1.7 °C in all current production areas, the projected changes in rainfall differ between the larger islands further to the north (Sumatra and Sulawesi), which will become wetter by 5–14 %, and the smaller islands further to the south (Java, Bali, Flores), which will become slightly drier. Therefore, overall climatic differences among the country’s coffee production zones are projected to become more pronounced.

The Maxent model, therefore, projected a strong decline of coffee suitability within the current growing areas by 2050 due mostly to temperature increases that would cause an upward movement of the climatically suitable belt. As a consequence, the climatically suitable area within the current growing zones would decrease dramatically from about 360,000 ha currently to a little over 57,000 ha in 2050 (Table 1). North Sumatra and Aceh would lose about 90 % of the suitable area in the current production zones; Sulawesi and Bali would be almost as significantly affected; and Flores would become effectively unsuitable for growing coffee (Figs. 1, 2). Only in Java, where the current coffee production zone is much smaller than the climatically suitable area, would the suitable area remain about the same.

The decreasing climatic suitability of current coffee production zones was also evident in the shift from higher suitability (green) to lower suitability (yellow) that is especially visible for Sumatra and Flores (Figs. 1, 2). While this is also true for the current coffee-producing areas of Sulawesi, some highland areas further to the north that were not classified as suitable under current conditions appeared as suitable in the warmer future climate, leading to an overall increase of the suitable area on that island (Fig. 1).

According to the model, the climatically suitable area outside the current coffee-growing zones would decrease from currently 324,000 to 183,000 ha by 2050. In combination with projections within the current coffee-growing areas, this would result in a total suitable area of 240,000 ha, one-third less than the currently suitable area within the coffee production zones (360,000 ha; Table 1).

Discussion

Impact on current Arabica coffee production zones

Most current Arabica coffee producers across the Indonesian islands will be severely affected by climate change, especially in North Sumatra, Aceh and Flores, but also in Sulawesi and Bali. Flores may actually cease to grow Arabica coffee within the coming decades. Through increasing temperatures, the climatically suitable zones for cultivating Arabica coffee will shift upward, and large areas that are currently under coffee will acquire climates that are not currently used for quality coffee production. This is projected to affect 84 % of the current coffee production zones. This does not mean that coffee could not be grown anymore in the areas classified as unsuitable, but that the climate would be sufficiently different from climates currently used for growing Arabica coffee in the country to expect significant impacts on productivity and quality (Table 2). Since coffee quality is sensitive to temperature, the general temperature increase could mean a decrease in quality, while the decrease in rainfall on the southern islands could also result in reduced yields. In very rainy parts of the northern islands, on the other hand, a further increase in rainfall might also negatively affect yields. For example, very low yields of <150 kg ha−1 have been recorded in Sulawesi (Marsh and Neilson 2007; Neilson et al. 2013). These appear to be at least partly due to the absence of a dry period sufficient to trigger abundant flowering and excessive rainfall resulting in poor fruit set. Higher temperatures and rainfall may compel farmers to switch from Arabica to other crops. These may include Robusta coffee (Coffea canephora), a related species better adapted to lowland conditions which is already grown in association with Arabica in some parts of Indonesia, but is considered a bulk product that commands a lower price on international markets. Pest and disease pressures may also change in a warmer and wetter climate (Garrett et al. 2011), notably through an upward expansion of the coffee berry borer (Hypothenemus hampei) (Jaramillo et al. 2009). This suggests that the next generation of existing coffee farmers, at least those not willing to migrate, may gradually have to modify livelihood strategies away from the cultivation of Arabica coffee.

Possible expansion of Arabica coffee production zones

While many current Arabica coffee farmers may have to change crops over coming decades, other farmers may migrate to higher altitudes and establish new coffee farms and potentially new settlements. By 2050, after climate change has taken its toll, the total area with climatically and topographically suitable conditions for growing Arabica coffee (240,000 ha) will be about one-third smaller than the suitable area in the current production zones (360,000 ha; Table 1). However, not all of that currently suitable area is actually used for growing coffee. Based on typical Indonesian yield levels of little over 0.5 t per ha (International Coffee Organization, http://www.ico.org/countries/indonesia.pdf), only approximately 186,000 ha are needed for producing Indonesia’s annual output of 93,000 t of Arabica coffee (average of the last 4 years, http://gain.fas.usda.gov/; see also Table S1). This reflects the fact that in Indonesia, Arabica coffee is mostly grown in small plots within a mosaic of other crops and land uses. Therefore, the estimated area suitable for Arabica coffee in 2050 (240,000 ha) would still be about 30 % larger than the area currently used for growing this crop. This does not include the large suitable areas within protected areas and protection forests, for example, in Aceh (Fig. 1). This suggests that production losses owing to climate change in current production zones could potentially be compensated by new coffee planting in areas that remain or become climatically suitable outside the current production zones. This compensation would especially be possible if the new plantings were managed more intensively than some of the old plantings that may go out of production.

The largest climatically suitable areas for such expansion (or relocation) of coffee farming by 2050 would be in Sulawesi, whose high mountain areas would become more climatically suitable for agriculture through rising temperatures (Fig. 1). Here, about 95,000 ha were classified as climatically suitable in 2050, over twice the suitable area in the current coffee production zone (Table 1). Although much of this area is now relatively inaccessible, it may become increasingly attractive for prospective coffee farmers over the coming decades as long as the predicted increases in rainfall don’t negatively affect yield potentials for these areas. Similar potential of coffee production to shift to areas outside the current production zone was also evident in Aceh (Table 1). In Indonesian Papua, where small amounts of Arabica coffee are currently grown at altitudes between 1,400 and 2,000 m, a substantial expansion potential may also exist based on physical suitability alone. This area was not included in our study, in part because social and political constraints are currently restricting coffee production there.

Winner or loser of climate change?

Our model only identified potentially suitable areas based on climate and topography. Some of these areas at higher altitudes may not be appropriate because of their remoteness, because they have poor soil or are under other land uses, or perhaps because they will be included in future protected areas. Social and economic constraints are also paramount, as coffee farming in Indonesia is highly labor intensive and ultimately depends on a population willing to work in the farms. Therefore, our results should not be seen as a prognosis of future developments in the Indonesian Arabica coffee sector, but rather as an indication of a potential that may or may not be realized, and an input into corresponding discussions and planning processes in the public and private sectors.

Whether coffee production ultimately expands into new climatically suitable areas will depend upon various factors that are almost impossible to predict at this stage, as it is likely that other agricultural commodities, such as vegetable and fruit crops, will face similar supply constraints and may be competing for access to the same land. The ability of lead firms in different commodity-dependent industries to effectively coordinate their supply chains to encourage and maintain production is likely to be a key factor affecting production choices at the farm level. Government decisions regarding support programs will also be influential. Ultimately, crop and livelihood choices will be strongly shaped by prevailing prices and market demand. These depend in part on the fate of other Arabica coffee origins in a changing climate. A number of studies have shown that the climatic suitability of major Arabica coffee origins in Latin America will strongly decline over the next decades (Eakin et al. 2006; Schroth et al. 2009; Rahn et al. 2014). The prospects of African Arabica coffee producer countries under climate change have not been studied to the same extent (Läderach and van Asten 2012), although available information suggests that impacts may be less severe than in Latin America. However, the probable reduction of production volumes and/or quality in Latin America may open a significant niche for other coffee producers such as Indonesia whose physical geography, according to our analysis, would allow current production levels to be maintained and perhaps even increased.

This relatively positive scenario, however, would require significant shifts among coffee production regions within the country. While Aceh may struggle to maintain its current level of production through a local shift in coffee areas, Arabica coffee output from North Sumatra is likely to decrease. Sulawesi, on the other hand, could potentially become a “relative climate change winner” despite the severe effects that climate change will have on current coffee-producing regions. Coffee production practices in Sulawesi are currently notably extensive and characterized by low per-hectare yields (Marsh and Neilson 2007). One can only speculate whether an increase in demand for its coffee as the output from other production regions within and outside Indonesia decreases might trigger intensification and expansion of current farms, and/or attract a wave of migrants, including perhaps climate-displaced coffee farmers from other parts of the country.

Environmental and policy implications

Coffee farming in Indonesia has a history of driving deforestation through forest frontier dynamics, often in combination with migration of farmers (Arifin et al. 2008; Neilson 2008; Gaveau et al. 2009b; Schroth et al. 2011). Sulawesi has emerged as a global hub of production for another tree crop, cocoa (Theobroma cacao), only in the last 30 years on the back of migrant farmers moving into previously underdeveloped lands from more densely populated areas of the country (Ruf et al. 1996). Therefore, an increase in demand for Indonesia’s coffee through production (and quality) decline elsewhere would almost certainly increase pressure on ecologically important mountain ecosystems (Wiramanayake et al. 2002) where many of Indonesia’s protected areas are located (Gaveau et al. 2009a). It is important, then, that the expansion of coffee land be encouraged into areas that will maintain their climatic suitability for coffee farming into the next decades, and that are not currently within protected areas and protection forests. Ideally, new coffee plantings should be encouraged into previously cleared areas where they can contribute positively to landscape restoration, especially if intercropped shaded practices are used as is common in many parts of Indonesia. Incentive models for stabilizing forest frontiers in coffee areas in Indonesia have been piloted (Schroth et al. 2011) and need wider application. This is an important task to be pursued jointly by government and the private sector (Arifin et al. 2008; Neilson 2008).

In consideration of the potential ecological effects of expanding high altitude coffee cultivation in Indonesia, it may be desirable to promote more intensive management practices in Indonesian coffee production (where yields are currently very low by global standards) as a means to limit the area needed for new planting as old coffee areas are becoming climatically unsuitable. Further, we suggest the need to carefully plan infrastructure development and to create new protected areas in those mountain regions that provide multiple ecosystem services, including biodiversity habitat and water provision (Wiramanayake et al. 2002). A changing climate is likely to place unprecedented demands on these ecosystems both to be agriculturally productive and to provision critical environmental services, and the potential for coffee to be cultivated within this contested landscape remains uncertain. Notwithstanding these caveats, this analysis has identified the climatic and topographic potential for the expansion of Arabica coffee within some islands of Indonesia, while other islands may face a medium-term decline of their Arabica coffee industry.

References

Arifin B, Geddes R, Ismono H, Neilson J, Pritchard B (2008) Farming at Indonesia’s forest frontier: understanding incentives for smallholders. Australian National University, Canberra

Baca M, Läderach P, Haggar JP, Schroth G, Ovalle O (2014) An integrated framework for assessing vulnerability to climate change and developing adaptation strategies for coffee growing families in Mesoamerica. PLoS One 9(2):e88463. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088463

Barbet-Massin M, Jiguet F, Albert CH, Thuiller W (2012) Selecting pseudo-absences for species distribution models: how, where and how many? Methods Ecol Evol 3:327–338. doi:10.1111/j.2041-210X.2011.00172.x

Brown ME, Funk CC (2008) Food security under climate change. Science 319:580–581. doi:10.1126/science.1154102

Eakin H, Tucker C, Castellanos E (2006) Responding to the coffee crisis: a pilot study of farmers’ adaptations in Mexico, Guatemala and Honduras. Geogr J 172:156–171. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4959.2006.00195.x

Garrett KA, Forbes GA, Savary S, Skelsey P, Sparks AH, Valdivia C, van Bruggen AHC, Willocquet L, Djurle A, Duveiller E, Eckersten H, Pande S, Vera Cruz C, Yuen J (2011) Complexity in climate-change impacts: an analytical framework for effects mediated by plant disease. Plant Pathol 50:15–30. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3059.2010.02409.x

Gaveau DLA, Epting J, Lyne O, Linkie M, Kumara I, Kanninen M, Leader-Williams N (2009a) Evaluating whether protected areas reduce tropical deforestation in Sumatra. J Biogeogr 36:2165–2175. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2009.02147.x

Gaveau DLA, Linkie M, Suyadi, Levang P, Leader-Williams N (2009b) Three decades of deforestation in southwest Sumatra: effects of coffee prices, law enforcement and rural poverty. Biol Conserv 142:597–605. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2008.11.024

Hannah L, Roehrdanz PR, Ikegami M, Shepard AV, Shaw MR, Tabor G, Zhi L, Marquet PA, Hijmans RJ (2013) Climate change, wine, and conservation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. doi:10.1073/pnas.1210127110

Hijmans RJ, Cameron SE, Parra JL, Jones PG, Jarvis A (2005) Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int J Climatol 25:1965–1978. doi:10.1002/joc.1276

ICO (2014) Trade Statistics, International Coffee Organization (ICO), London. http://www.ico.org. Accessed 11 Nov 2013

Jaramillo J, Chabi-Olaye A, Kamonjo C, Jaramillo A, Vega FE, Poehling HM, Borgemeister C (2009) Thermal tolerance of the coffee berry borer Hypothenemus hampei: predictions of climate change impact on a tropical insect pest. PLoS One 4:e6487. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006487

Läderach P, van Asten P (2012) Coffee and climate change. Coffee suitability in East Africa. In: 9th African fine coffee conference and exhibition, Addis Ababa

Läderach P, Martinez A, Schroth G, Castro N (2013) Predicting the future climatic suitability for cocoa farming of the world’s leading producer countries, Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire. Clim Chang 119:841–854. doi:10.1007/s10584-013-0774-8

Liu C, White M, Newell G (2013) Selecting thresholds for the prediction of species occurrence with presence-only data. J Biogeogr 40:778–789. doi:10.1111/jbi.12058

Lobell DB, Burke MB, Tebaldi C, Mastrandrea MD, Falcon WP, Naylor RL (2008) Prioritizing climate change adaptation needs for food security in 2030. Science 319:607–610. doi:10.1126/science.1152339

Lobo JM, Tognelli MF (2011) Exploring the effects of quantity and location of pseudo-absences and sampling biases on the performance of distribution models with limited point occurrence data. J Nat Conserv 19:1–7. doi:10.1016/j.jnc.2010.03.002

Marsh T, Neilson J (2007) Securing the profitability of the Toraja coffee industry. ACIAR, Canberra

Neilson J (2008) Global private regulation and value-chain restructuring in Indonesian smallholder coffee systems. World Dev 36:1607–1622. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.09.005

Neilson J, Hartari DSF, Lagerqvist YF (2013) Coffee-based livelihoods in South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Appendix 8 to the final report for ACIAR Project SMAR/2007/063. Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research, Canberra

Peterson AT, Papes M, Soberón J (2008) Rethinking receiver operating characteristic analysis applications in ecological niche modeling. Ecol Model 213:63–72. doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2007.11.008

Phillips SJ, Anderson RP, Schapire RE (2006) Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol Model 190:231–259. doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2005.03.026

Rahn E, Läderach P, Baca M, Cressy C, Schroth G, Malin D, van Rikxoort H, Shriver J (2014) Climate change adaptation and mitigation in coffee production: where are the synergies? Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Chang. doi:10.1007/s11027-013-9467-x

Ramirez-Villegas J, Jarvis A (2010) Downscaling global circulation model outputs: the delta method. Decision and policy analysis working paper no. 1. CIAT, Cali

Ruf F, Ehrut P, Yoddang (1996) Smallholder cocoa in Indonesia: why a boom in Sulawesi? In: Clarence-Smith WG (ed) Cocoa pioneer fronts since 1800: the role of smallholders. Planters and Merchants, Macmillan, pp 212–231

Schroth G, Ruf F (2014) Farmer strategies for tree crop diversification in the humid tropics. Rev Agron Sustain Dev 34:139–154. doi:10.1007/s13593-013-0175-4

Schroth G, Läderach P, Dempewolf J, Philpott SM, Haggar JP, Eakin H, Castillejos T, Garcia-Moreno J, Soto-Pinto L, Hernandez R, Eitzinger A, Ramirez-Villegas J (2009) Towards a climate change adaptation strategy for coffee communities and ecosystems in the Sierra Madre de Chiapas, Mexico. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Chang 14:605–625. doi:10.1007/s11027-009-9186-5

Schroth G, da Mota MSS, Hills T, Soto-Pinto L, Wijayanto I, Arief CW, Zepeda Y (2011) Linking carbon, biodiversity and livelihoods near forest margins: the role of agroforestry. In: Kumar BM, Nair PKR (eds) Carbon sequestration in agroforestry: processes, policy, and prospects. Springer, Berlin, pp 179–200. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-1630-8_10

Sheng TC (1989) Soil conservation for small farmers in the humid tropics. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome

Thornton PK, van de Steeg J, Notenbaert A, Herrero M (2009) The impacts of climate change on livestock and livestock systems in developing countries: a review of what we know and what we need to know. Agric Syst 101:113–127. doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2009.05.002

Tucker CM, Eakin H, Castellanos EJ (2010) Perceptions of risk and adaptation: coffee producers, market shocks, and extreme weather in Central America and Mexico. Glob Environ Chang 20:23–32. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.07.006

UNEP-WCMC (2012) Data standards for the world database on protected areas. United Nations Environment Programme—World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge

Vermeulen S, Aggarwal PK, Ainslie A, Angelone C, Campbell BM, Challinor AJ, Hansen JW, Ingram JSI, Jarvis A, Kristjanson P, Lau C, Nelson GC, Thornton PK, Wollenberg E (2012) Options for support to agriculture and food security under climate change. Environ Sci Policy 15:136–144. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2011.09.003

Wiramanayake E, Dinerstein E, Loucks CJ, Olson DM, Morrison J, Lamoreux J, McKnight M, Hedao P (2002) Terrestrial ecoregions of the Indo-Pacific—a conservation assessment. Island Press, Washington, DC

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted under the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). We would like to thank Ina Murwani and the Specialty Coffee Association of Indonesia for permission to use the coffee maps of Indonesia that were produced as part of the USAID funded Amarta project, as well as DAI for facilitating access to the maps. Dwi Nurcahyadi from the Department of Geography of the University of Indonesia kindly shared spatial information on protection forests and other national protection categories. Tony Marsh provided critical input during key stages of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Editor: Christopher Reyer.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Schroth, G., Läderach, P., Blackburn Cuero, D.S. et al. Winner or loser of climate change? A modeling study of current and future climatic suitability of Arabica coffee in Indonesia. Reg Environ Change 15, 1473–1482 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-014-0713-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-014-0713-x