Abstract

Patients with diabetes mellitus have an increased risk of developing tuberculosis. Although the underlying mechanism is unclear, evidence suggests a role for chronic hyperglycaemia. We examined the influence of hyperglycaemia on Mycobacterium tuberculosis-induced cytokine responses in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1D). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from 24 male T1D patients with sub-optimal glucose control [HbA1c > 7.0% (53 mmol/L)] and from 24 age-matched male healthy controls were stimulated with M. tuberculosis lysate. Cytokine analysis, assessment of aerobic glycolysis, receptor recognition and serum cross-over experiments were performed to explore the mechanistic differences. PBMCs from T1D patients produced less bioactive interleukin (IL)-1β in response to M. tuberculosis. IL-6 and interferon (IFN)-γ production trended towards a decrease, whilst other cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-17 and IL-1Ra were normal. The decrease in cytokine production was not correlated to HbA1c or plasma glucose levels. Cross-over serum experiments did not alter the cytokine profile of T1D or control patients, arguing for an intrinsic cellular defect. Cellular metabolism and the expression of M. tuberculosis-related pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) such as TLR2, TLR4 and NOD2 did not differ between T1D patients and healthy controls. Compared to matched controls, T1D patients have a reduced capacity to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines in response to M. tuberculosis. The impaired IL-1β production in T1D patients may contribute to the increased susceptibility to tuberculosis. This effect appears not to be related to prevailing glucose levels but to an intrinsic cellular deficit.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Diabetes increases the risk of developing active tuberculosis (TB) and is associated with worsened outcomes during TB treatment. It has been estimated that 15% of TB cases globally can be attributed to diabetes [1]. Patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D) may have an even higher risk of developing TB compared to those with type 2 diabetes (T2D) [2,3,4]. Additionally, poor glucose control escalates the risk of TB [5, 6]. The epidemiological evidence for the relation between diabetes and TB is strong, but the molecular and immunological basis for the susceptibility to TB remains largely unclear.

Recent evidence that points towards a disturbed innate and adaptive immune response to TB is mainly derived from studies in T2D patients [7]. However, T2D is a multi-factorial disease involving age, obesity, sedentary lifestyle and genetics. It is characterised by hyperglycaemia, insulin resistance, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and oxidative stress. All these factors, including the use of anti-diabetic drugs with potential immune-modulating capacities (i.e. metformin), make it difficult to specifically examine the role of hyperglycaemia in the increased susceptibility to TB.

Therefore, we sought to study the response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis in T1D patients with chronic hyperglycaemia. We excluded individuals using drugs other than insulin replacement therapy and also those with serious diabetic complications. We examined whether T1D is associated with altered production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor TNF, interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-6 from monocytes and interferon (IFN)-γ from CD4+ lymphocytes, all of which are pivotal for effective host defences against TB [8]. Finally, we examined whether external factors in serum (i.e. hyperglycaemia) or intrinsic factors (i.e. cellular metabolism and expression of pattern recognition receptors, PRRs) were responsible for differences in cytokine responses between healthy controls and T1D patients.

Materials and methods

Recruitment and characterisation of study subjects

We enrolled 24 male T1D patients with an HbA1c > 7.0% (53 mmol/L) and 24 age-matched male healthy controls. Participants were all between 20 and 70 years old. For T1D patients, the minimal duration of diabetes was 1 year. Patients using medication other than insulin were excluded. HbA1c was measured by standard laboratory methods. Plasma insulin was measured by radioimmunoassay [9]. Plasma cholesterol, triglyceride (TG), glucose (Liquicolor; Human GmbH, Wiesbaden, Germany) and free fatty acids (NEFA C; WAKO Chemicals, GmbH, Neuss, Germany) were measured enzymatically following the manufacturers’ protocols. Blood was drawn from a cubital vein and collected into sterile EDTA tubes for isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or from serum tubes (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The study was approved by the institutional review board and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Using similar criteria, an additional six T1D and six controls were recruited for a follow-up experiment.

PBMC isolation and stimulation

PBMC isolation was performed by dilution of blood in pyrogen-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and differential density centrifugation over Ficoll-Paque (GE Healthcare, Zeist, The Netherlands). Cells were washed twice in PBS and re-suspended in RPMI culture medium (Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium; MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA) supplemented with 5 mM glucose, 10 μg/mL gentamicin, 10 mM L-glutamine and 10 mM pyruvate. PBMCs were counted with a Coulter counter (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA) and adjusted to 5 × 106 cells/mL. A 100-μL volume was added to round-bottom 96-well plates (Corning, New York, USA) for PBMC stimulation experiments. Excess unstimulated PBMCs were lysed in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Breda, The Netherlands) and stored at − 80 °C until RNA isolation was performed.

Cells were stimulated with RPMI, 1 μg/mL M. tuberculosis (H37Rv) lysate for 24 h or 7 days (in the presence of 10% human pool serum for lymphocyte-derived cytokines). For serum cross-over experiments, cells were incubated with 25% serum for 24 h or 7 days. In a follow-up experiment, we collected six additional male T1D patients with an HbA1c > 7.0% and six age-matched male healthy controls. PBMCs were isolated and stimulated with Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (from E. coli serotype 055:B5; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA; 1 ng/mL or 10 ng/ml). Supernatants were collected and stored at − 20 °C until cytokine/lactate measurements were performed.

Cytokine measurements

Cytokine measurements from cell culture supernatants were performed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA); namely, IL-1β, IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra), TNF-α (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and IL-6 (Sanquin, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) were measured in the 24-h PBMC stimulation experiments. Supernatants of the 7-day stimulations were used to measure IL-22, IL-17 (R&D Systems) or IFN-γ (Sanquin).

Bioactive IL-1 assay

Active IL-1 was measured indirectly using the mouse thymoma EL4-NOB1 (NOB1) cell line. NOB1 cells were cultured in RPMI culture medium supplemented with 1 mM pyruvate, 1 mM GlutaMAX, 1 mM penicillin/streptomycin and 10% foetal bovine serum (Gibco, Burlington, Ontario, Canada) until confluence was reached. NOB1 cells (105 cells/well) were plated in a flat-bottom 96-well plate (Corning). 70 μL (2× dilution) of supernatant from PBMCs of T1D or healthy controls that were stimulated with M. tuberculosis were added to each well. Cytokine measurement for murine IL-2 was performed by ELISA (R&D Systems).

Lactate measurements

Lactate was measured from cell culture supernatants using a coupled enzymatic assay in which lactate was oxidised and the resulting H2O2 was coupled to the conversion of Amplex® Red reagent to fluorescent resorufin by horseradish peroxidase (HRP). 30 μL of lactate standard or 200-fold diluted sample was added to a black 96-well flat-bottom plate, followed by 30 μL of reaction mix, which consisted of 0.6 μL of 10 U/mL HRP (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.6 μL of 100 U/mL lactate oxidase (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.3 μL of 10 mM Amplex® Red reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 28.5 μL PBS. The assay was incubated for 20 min at room temperature (RT) and the fluorescence of resorufin (excitation/emission maxima = 570/585 nm) was measured on a 96-well plate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA).

Transcriptional analysis of isolated PBMCs

RNA was isolated from unstimulated PBMCs using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA was transcribed into complementary DNA by reverse-transcription using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was performed using different primer sets (Biolegio, Malden, The Netherlands); primer sequences for hexokinase (HK) 2, HK3, 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3), pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (PDK4), malate dehydrogenase (MDH) 1, MDH2, toll-like receptor (TLR) 2, TLR4, nucleotide-binding oligomerisation domain containing 2 (NOD2), caspase recruitment domain family member 9 (CARD9), receptor interacting serine/threonine kinase 2 (RIPK2), mitogen-activated protein kinase 9 (MAPK9), TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) and caspase 1 (CASP-1) are given in Supplementary Table 1. Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used for qPCR in a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). qPCR data were normalised to the housekeeping gene human β2M.

Statistics

Data are shown as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Differences in cytokine secretion were calculated using the Mann–Whitney test for two independent samples. Correlation analysis between glucose metabolites and cytokine secretion was performed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient and the 95% confidence interval was calculated accordingly. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Generation of graphs and statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5.

Results

The participant’s characteristics are shown in Table 1. Age, plasma TG and free fatty acid (FFA) levels were not different between T1D patients and the 24 control subjects (Table 1). As per definition, HbA1c and plasma glucose levels were significantly increased in T1D patients compared to healthy controls. Plasma insulin levels were also higher, whilst plasma cholesterol levels were lower in T1D patients.

PBMCs of T1D patients show reduced pro-inflammatory IL-1β cytokine secretion in response to M. tuberculosis

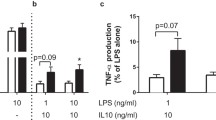

No spontaneous cytokine production was detected in unstimulated TID patients or control cells (RPMI; Fig. 1). In contrast, robust induction of cytokine production was observed in response to M. tuberculosis in both groups. The production of IL-1β was significantly lower in T1D patients as compared to healthy controls (p < 0.01; Fig. 1). IL-6 and IFN-γ followed a similar trend, albeit at borderline significance (p = 0.06). TNF-α, IL-1Ra, IL-17 and IL-22 levels were not different between T1D patients and controls (Fig. 1). The decrease in IL-1β production was not specific to M. tuberculosis stimulation. Six additionally recruited T1D patients also produced lower levels of IL-1β in response to high-dose LPS stimulation (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1D) subjects secrete less interleukin (IL)-1β upon stimulation with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PBMCs (5 × 105/well) from T1D patients and healthy control subjects were stimulated with 1 μg/mL M. tuberculosis lysate. Secretion of: a IL-1β, b IL-6, c IL-1Ra and d tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α were measured in supernatants by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) after 24 h of stimulation. e Interferon (IFN)-γ, f IL-17 and g IL-22 were measured after 7 days of stimulation. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) from n = 24 individuals per group. **p < 0.01 compared with matched healthy controls

Correlation of IL-1β cytokine secretion with glycaemia

To determine whether the lower cytokine production in PBMCs from T1D patients in response to M. tuberculosis stimulation was related to glucose control, cytokine production was correlated with HbA1c and glucose. However, there were no correlations between M. tuberculosis-induced IL-1β, IL-6 or IFN-γ secretion from PBMCs and HbA1c or plasma glucose levels of T1D patients (Fig. 2). Also, no correlations were found between cytokine secretion and duration of diabetes (Supplementary Fig. 2). IL-1β secretion strongly correlated with IL-6 secretion in response to M. tuberculosis, but there were no other correlations between cytokine responses.

Correlation of cytokine secretion with glycaemia. Associations for T1D patients between glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c%), plasma glucose levels and secretion of IL-1β, IL-6 and IFN-γ from PBMCs after stimulation with 1 μg/mL M. tuberculosis lysate. a Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients for all associations. b Correlations are shown by linear fitted curves and 95% confidence intervals for T1D subjects (n = 24)

Influence of serum and cellular metabolism on cytokine production

The cross-over of autologous serum from control to T1D and vice versa did not influence cytokine production of either subject group (Fig. 3). This suggests that the reduced IL-1β secretion is not directly related to plasma glucose concentration or other serum factors; instead, it is likely to be an intrinsic defect within the immune cells of T1D patients.

Influence of T1D serum on cytokine production in response to M. tuberculosis. PBMCs (5 × 105 cells/well) of healthy control (CON) subjects were incubated in either 25% of autologous serum or 25% of serum from an age-matched type 1 diabetes (T1D) subject and vice versa for PBMCs from T1D subjects. Secretion of: a IL-1β, b IL-6 and c TNF-α were measured in the supernatants using ELISA after 24 h of exposure to M. tuberculosis. d INF-γ, e IL-22 and f IL-17 were determined after 7 days. Data are mean ± SEM from n = 24 individuals per group. *p < 0.05 compared with healthy controls

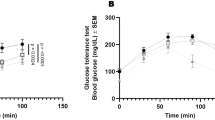

Activation of aerobic glycolysis is important for cytokine production in response to M. tuberculosis [10]. However, lactate production, a marker of glycolysis, was not decreased in T1D patients. In fact, M. tuberculosis stimulation increased lactate production in T1D patients compared to matched healthy controls (Fig. 4a). Glucose consumption (Fig. 4b) and the expression levels of glycolysis genes HK2, HK3 and PFKFB3 in PBMCs was similar between T1D patients and healthy controls (Fig. 4e–g). Finally, no difference in the expression of the TCA cycle genes PDK4, MDH1 and MDH2 (Fig. 4h–j) was observed.

Cellular metabolism in PBMCs from T1D subjects and controls. a Lactate secretion and c glucose consumption were measured in the supernatant of unstimulated (RPMI) PBMCs of type 1 diabetes (T1D) and healthy control (CON) subjects as well as b, d after 24 h of stimulation with M. tuberculosis lysate. Relative mRNA expression values of e HK2, f HK3, g PFKFB3, h PDK4, i MDH1 and j MDH2 in unstimulated PBMCs from T1D and CON subjects. Data are mean ± SEM from n = 24 individuals per group

Mycobacterium tuberculosis recognition and downstream signalling

To determine whether changes in receptors involved in M. tuberculosis recognition could explain the impaired cytokine response of PBMCs from T1D patients, we investigated the gene expression levels of well-known M. tuberculosis PRRs in PBMCs of both groups. Levels of TLR2, TLR4 and NOD2 were unchanged (Fig. 5a–c). In addition, no differences were found in the expression of genes involved in the intracellular signalling response to M. tuberculosis, including CARD9, RIPK2, MAPK9, TRAF6 and CASP1 (Fig. 5d–h).

Mycobacterium tuberculosis recognition and downstream signalling. Relative basal mRNA expression values of PBMCs from type 1 diabetes (T1D) patients are shown when compared to matched healthy controls (CON) for a TLR2, b TLR4, c NOD2, d CARD9, e RIPK2, f MAPK9, g TRAF6 and h CASP1. Data are mean ± SEM from n = 24 individuals per group

Bioactive IL-1 secretion from PBMCs of T1D patients

To determine whether differences in cellular processing affected the secretion of IL-1β, we determined the amount of bioactive IL-1 in the supernatants of PBMCs stimulated with M. tuberculosis from Fig. 1 (Fig. 6). We found that PBMCs of T1D patients released significantly lower levels of bioactive IL-1 in response to M. tuberculosis .

Bioactive IL-1 secretion from PBMCs of T1D patients. PBMCs (5 × 105/well) from type 1 diabetes patients (T1D) and healthy control subjects (CON) were stimulated with 1 μg/mL M. tuberculosis lysate for 24 h and supernatants were subsequently incubated with the murine thymoma EL4-NOB1 cell line (105 cells/well). Mouse IL-2 cytokine secretion in response to present bioactive IL-1 in the supernatant of the PBMCs was measured using ELISA. Data are mean ± SEM from n = 24 individuals per group. *p < 0.05 compared with the matched healthy controls

Discussion

The primary finding of this study is that PBMCs from patients with T1D have a reduced ability to produce IL-1β, IL-6 and IFN-γ in response to M. tuberculosis stimulation, while TNF, IL-17 and IL-1Ra production is normal. These changes may be partly responsible for the well-known susceptibility of patients with diabetes for TB. The current data suggest that the decreased cytokine production after stimulation with M. tuberculosis is an intrinsic cellular deficit in PBMCs from T1D patients, since differences in cytokine secretion were not due to external factors in serum or related to glucose regulation.

Epidemiological studies that investigated the relation between hyperglycaemia and the risk for TB have been contradicting. Both a positive effect [5, 6] and no effect [11,12,13] of hyperglycaemia on the risk for TB have been described. These studies vary greatly in size, geography and definition of controlled versus uncontrolled glycaemia. To our knowledge, this is the first study specifically examining the cytokine production capacity of T1D patients to M. tuberculosis. At the same time, studies on the cytokine response to other pathogenic stimuli such as LPS strongly support our findings. Ex vivo stimulation experiments performed in both T1D [14,15,16] and T2D [17, 18] patients describe a similar decrease of IL-1β and IL-6 but not TNF-α, IL-1Ra and IFN-γ production, respectively. As shown in the stimulation experiments with LPS, this decrease in cytokine signalling is not specific for M. tuberculosis, thus supporting the notion that an intrinsic defect in cytokine production rather than an M. tuberculosis-specific signalling defect is the mechanism underlying the decrease in cytokine production. This may also explain why T1D patients are also susceptible to other (common) infections, such as lower respiratory tract infection, urinary tract infection, and skin and mucous membrane infection [19, 20].

Interestingly, patients with both TB and diabetes produce more cytokines compared to patients with only TB [21, 22]. Together, these findings suggest an initial sub-optimal response to infection which promotes bacterial growth and subsequent pathology. This hypothesis of a delayed immune response is supported by a mouse model of concomitant TB and diabetes disease [23].

The exact type of intracellular defects remains to be elucidated. No change in aerobic glycolysis was observed nor altered expression of relevant PRRs. It is possible that a certain level of accelerated immunosenescence occurs in T1D. This process, described for aging, is characterised by impaired cellular immune function (leading to increased death due to infectious diseases), simultaneously with increased chronic inflammatory activity (leading to increased incidence of cardiovascular disease) [24]. The observations that T1D patients show enhanced low-grade chronic inflammation and cardiovascular diseases [25] and, at the same time, an impaired immune response to pathogens as observed in the current study support this hypothesis. The decrease in IL-6 may be a secondary effect as IL-1β induces IL-6 production in a paracrine signalling loop. Similarly, IL-18, another product of caspase-1 activity, is important for IFN-γ production. This could explain why the decrease in these cytokines is more subtle as compared to IL-1β. This avenue will form a cornerstone for further research.

The implications of a decrease in IL-1β production for susceptibility to TB are significant. In a murine model of TB, IL-1α/β double knockout mice [26] or mice deficient in IL-1R1 [27] display increased susceptibility to M. tuberculosis infection. Although the spectra of human and mouse TB do not completely overlap, there are firm established points of convergence [28]. Therefore, these mouse studies suggest that IL-1 has an important role in the generation of an adequate host defence against TB. In humans, a positive association between IL-1β levels and resistance to TB was inferred from human IL1B gene polymorphisms [29]. Moreover, patients with gain-of-function mutations in the inflammasome component NLRP3 have an increased capacity to kill M. tuberculosis [30]. Mechanistically, a recent study elucidated that IL-1β promoted bacterial containment through the induction of specific eicosanoids that limited excessive type 1 IFN-γ production [31]. The current study was performed in T1D patients, with chronic hyperglycaemia as a key characteristic. The observed impaired cellular cytokine response could be similar for T2D patients. However, T2D is a much more heterogeneous disease characterised by multiple metabolic disturbances (i.e. hyperglycaemia, insulin resistance, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and oxidative stress), which may further contribute to the increased susceptibility to TB and which needs further investigation.

As a limitation of this study, we did not investigate other host defence mechanisms such as phagocytosis, reactive oxygen species (ROS) or nitric oxide (NO) production from monocytes or macrophages, since it is unlikely that reduced IL-1β is the sole factor in susceptibility to TB. A confounding factor in the current study could be the significantly higher levels of insulin in blood of T1D patients, as insulin can affect cytokine production; however, we did not find any correlation between insulin and cytokine production in T1D patients (Supplementary Fig. 3). Lastly, another limitation of this study is the relatively small size of our cohort, as a result of which subtle associations such as those between glucose control and cytokine responses may not be detectable. We chose to study only male patients and healthy controls in order to reduce variability in the cytokine response as much as possible, hence enabling the generation of robust results with 24 individuals per group. Indeed, for example, oral contraceptive usage in women has been shown to significantly impact on cytokine secretion from PBMCs [32]. Although we cannot completely exclude differences of cytokine production between male and female diabetes patients, no differences have been observed previously between healthy men and women regarding the IL-1β response to M. tuberculosis [32], suggesting that our results derived from male participants are most likely relevant for both men and women.

In conclusion, this study specifically identifies a decrease in bioactive IL-1β to possibly be, due to a deficit in intracellular processing rather than chronic hyperglycaemia, a strong candidate in the susceptibility of T1D patients to TB.

References

Riza AL, Pearson F, Ugarte-Gil C, Alisjahbana B, van de Vijver S, Panduru NM, Hill PC, Ruslami R, Moore D, Aarnoutse R, Critchley JA, van Crevel R (2014) Clinical management of concurrent diabetes and tuberculosis and the implications for patient services. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2(9):740–753. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70110-X

Swai AB, McLarty DG, Mugusi F (1990) Tuberculosis in diabetic patients in Tanzania. Trop Doct 20(4):147–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/004947559002000402

Dobler CC, Flack JR, Marks GB (2012) Risk of tuberculosis among people with diabetes mellitus: an Australian nationwide cohort study. BMJ Open 2(1):e000666. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000666

Shen TC, Lin CL, Wei CC, Liao WC, Chen WC, Chen CH, Tu CY, Hsia TC, Shih CM, Hsu WH, Li CH, Sung FC (2014) Increased risk of tuberculosis in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus: results from a population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Medicine (Baltimore) 93(16):e96. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000000096

Lee PH, Fu H, Lai TC, Chiang CY, Chan CC, Lin HH (2016) Glycemic control and the risk of tuberculosis: a cohort study. PLoS Med 13(8):e1002072. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002072

Leung CC, Lam TH, Chan WM, Yew WW, Ho KS, Leung GM, Law WS, Tam CM, Chan CK, Chang KC (2008) Diabetic control and risk of tuberculosis: a cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 167(12):1486–1494. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwn075

Ronacher K, Joosten SA, van Crevel R, Dockrell HM, Walzl G, Ottenhoff TH (2015) Acquired immunodeficiencies and tuberculosis: focus on HIV/AIDS and diabetes mellitus. Immunol Rev 264(1):121–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/imr.12257

van Crevel R, Ottenhoff TH, van der Meer JW (2002) Innate immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 15(2):294–309

Abbink EJ, Walker AJ, van der Sluijs HA, Tack CJ, Smits P (2002) No role of calcium- and ATP-dependent potassium channels in insulin-induced vasodilation in humans in vivo. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 18(2):143–148. https://doi.org/10.1002/dmrr.269

Lachmandas E, Beigier-Bompadre M, Cheng SC, Kumar V, van Laarhoven A, Wang X, Ammerdorffer A, Boutens L, de Jong D, Kanneganti TD, Gresnigt MS, Ottenhoff TH, Joosten LA, Stienstra R, Wijmenga C, Kaufmann SH, van Crevel R, Netea MG (2016) Rewiring cellular metabolism via the AKT/mTOR pathway contributes to host defence against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in human and murine cells. Eur J Immunol 46(11):2574–2586. https://doi.org/10.1002/eji.201546259

Pealing L, Wing K, Mathur R, Prieto-Merino D, Smeeth L, Moore DA (2015) Risk of tuberculosis in patients with diabetes: population based cohort study using the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink. BMC Med 13:135. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0381-9

Chiang CY, Bai KJ, Lin HH, Chien ST, Lee JJ, Enarson DA, Lee TI, Yu MC (2015) The influence of diabetes, glycemic control, and diabetes-related comorbidities on pulmonary tuberculosis. PLoS One 10(3):e0121698. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0121698

Leegaard A, Riis A, Kornum JB, Prahl JB, Thomsen VØ, Sørensen HT, Horsburgh CR, Thomsen RW (2011) Diabetes, glycemic control, and risk of tuberculosis: a population-based case–control study. Diabetes Care 34(12):2530–2535. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc11-0902

Ohno Y, Aoki N, Nishimura A (1993) In vitro production of interleukin-1, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 77(4):1072–1077. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.77.4.8408455

Foss-Freitas MC, Foss NT, Rassi DM, Donadi EA, Foss MC (2008) Evaluation of cytokine production from peripheral blood mononuclear cells of type 1 diabetic patients. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1150:290–296. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1447.053

Mooradian AD, Reed RL, Meredith KE, Scuderi P (1991) Serum levels of tumor necrosis factor and IL-1alpha and IL-1beta in diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 14(1):63–65

Stalenhoef JE, Alisjahbana B, Nelwan EJ, van der Ven-Jongekrijg J, Ottenhoff TH, van der Meer JW, Nelwan RH, Netea MG, van Crevel R (2008) The role of interferon-gamma in the increased tuberculosis risk in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 27(2):97–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-007-0395-0

Kumar NP, Banurekha VV, Nair D, Sridhar R, Kornfeld H, Nutman TB, Babu S (2014) Coincident pre-diabetes is associated with dysregulated cytokine responses in pulmonary tuberculosis. PLoS One 9(11):e112108. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0112108

Muller LM, Gorter KJ, Hak E, Goudzwaard WL, Schellevis FG, Hoepelman AI, Rutten GE (2005) Increased risk of common infections in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Infect Dis 41(3):281–288. https://doi.org/10.1086/431587

Geerlings SE, Hoepelman AI (1999) Immune dysfunction in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM). FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 26(3-4):259–265

Kumar NP, Sridhar R, Banurekha VV, Jawahar MS, Nutman TB, Babu S (2013) Expansion of pathogen-specific T-helper 1 and T-helper 17 cells in pulmonary tuberculosis with coincident type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Infect Dis 208(5):739–748. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jit241

Kumar NP, Sridhar R, Banurekha VV, Jawahar MS, Fay MP, Nutman TB, Babu S (2013) Type 2 diabetes mellitus coincident with pulmonary tuberculosis is associated with heightened systemic type 1, type 17, and other proinflammatory cytokines. Ann Am Thorac Soc 10(5):441–449. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201305-112OC

Martens GW, Arikan MC, Lee J, Ren F, Greiner D, Kornfeld H (2007) Tuberculosis susceptibility of diabetic mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 37(5):518–524. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2006-0478OC

Shaw AC, Goldstein DR, Montgomery RR (2013) Age-dependent dysregulation of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 13(12):875–887. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri3547

Astrup AS, Tarnow L, Pietraszek L, Schalkwijk CG, Stehouwer CD, Parving HH, Rossing P (2008) Markers of endothelial dysfunction and inflammation in type 1 diabetic patients with or without diabetic nephropathy followed for 10 years: association with mortality and decline of glomerular filtration rate. Diabetes Care 31(6):1170–1176. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc07-1960

Yamada H, Mizumo S, Horai R, Iwakura Y, Sugawara I (2000) Protective role of interleukin-1 in mycobacterial infection in IL-1 alpha/beta double-knockout mice. Lab Investig 80(5):759–767

Juffermans NP, Florquin S, Camoglio L, Verbon A, Kolk AH, Speelman P, van Deventer SJ, van Der Poll T (2000) Interleukin-1 signaling is essential for host defense during murine pulmonary tuberculosis. J Infect Dis 182(3):902–908. https://doi.org/10.1086/315771

Kramnik I, Beamer G (2016) Mouse models of human TB pathology: roles in the analysis of necrosis and the development of host-directed therapies. Semin Immunopathol 38(2):221–237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00281-015-0538-9

Wilkinson RJ, Patel P, Llewelyn M, Hirsch CS, Pasvol G, Snounou G, Davidson RN, Toossi Z (1999) Influence of polymorphism in the genes for the interleukin (IL)-1 receptor antagonist and IL-1beta on tuberculosis. J Exp Med 189(12):1863–1874

Eklund D, Welin A, Andersson H, Verma D, Söderkvist P, Stendahl O, Särndahl E, Lerm M (2014) Human gene variants linked to enhanced NLRP3 activity limit intramacrophage growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Infect Dis 209(5):749–753. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jit572

Mayer-Barber KD, Andrade BB, Oland SD, Amaral EP, Barber DL, Gonzales J, Derrick SC, Shi R, Kumar NP, Wei W, Yuan X, Zhang G, Cai Y, Babu S, Catalfamo M, Salazar AM, Via LE, Barry CE 3rd, Sher A (2014) Host-directed therapy of tuberculosis based on interleukin-1 and type I interferon crosstalk. Nature 511(7507):99–103. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13489

ter Horst R, Jaeger M, Smeekens SP, Oosting M, Swertz MA, Li Y, Kumar V, Diavatopoulos DA, Jansen AF, Lemmers H, Toenhake-Dijkstra H, van Herwaarden AE, Janssen M, van der Molen RG, Joosten I, Sweep FC, Smit JW, Netea-Maier RT, Koenders MM, Xavier RJ, van der Meer JW, Dinarello CA, Pavelka N, Wijmenga C, Notebaart RA, Joosten LA, Netea MG (2016) Host and environmental factors influencing individual human cytokine responses. Cell 167(4):1111–1124.e13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.018

Funding

E.L. and R.v.C. were supported by the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (EU FP7) project TANDEM (HEALTH-F3-2012-305,279). K.T. and J.A.v.D. were supported by the Dutch Diabetes Research Foundation (#2013.81.1674). M.G.N. was supported by an ERC Consolidator Grant (#310372) and a Spinoza grant of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research. J.A.v.D. was supported by a Veni Grant of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (#91616083).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Additionally, this study was approved by the institutional review board. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOC 1314 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lachmandas, E., Thiem, K., van den Heuvel, C. et al. Patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus have impaired IL-1β production in response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis . Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 37, 371–380 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-017-3145-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-017-3145-y