Abstract

The treatment of choice of H. pylori infections is a 7-day triple-therapy with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) plus amoxicillin and either clarithromycin or metronidazole, depending on local antibiotic resistance rates. The data on efficacy of eradication therapy in a group of rheumatology patients on long-term NSAID therapy are reported here. This study was part of a nationwide, multicenter RCT that took place in 2000–2002 in the Netherlands. Patients who tested positive for H. pylori IgG antibodies were included and randomly assigned to either eradication PPI-triple therapy or placebo. After completion, follow-up at 3 months was done by endoscopy and biopsies were sent for culture and histology. In the eradication group 13% (20/152, 95% CI 9–20%) and in the placebo group 79% (123/155, 95% CI 72–85%) of the patients were H. pylori positive by histology or culture. H. pylori was successfully eradicated in 91% of the patients who were fully compliant to therapy, compared to 50% of those who were not (difference of 41%; 95% CI 18–63%). Resistance percentages found in isolates of the placebo group were: 4% to clarithromycin, 19% to metronidazole, 1% to amoxicillin and 2% to tetracycline.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

H. pylori eradication is strongly recommended in all patients with atrophic gastritis and peptic ulcer disease, but may also benefit subgroups of patients with dyspepsia, and patients who start with NSAID therapy [1–6]. H. pylori eradication therapy is an important component of guidelines concerning these patients [7, 8].

Currently, non-invasive management strategies and the widespread shortage in endoscopic capacity insure that many patients with H. pylori are managed without upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. The American College of Gastroenterology recommends that when an endoscopy is not performed, a serological test, which is the least expensive means of evaluating for evidence of H. pylori infection, should be done [9]. When endoscopy is indicated, biopsy specimens can be taken for microscopic demonstration of the organism, culture, histology or urease testing. Nowadays, in the Netherlands, biopsies are not routinely sent for culture and susceptibility testing of the infecting strain because of the high costs.

Apart from patient compliance, resistance of Helicobacter pylori to antibiotics can decrease the success of H. pylori eradication therapy. Regimens of choice for eradication of H. pylori should be guided by local antibiotic resistance rates. In the Netherlands, the overall prevalence of resistance to clarithromycin and metronidazol was lower than in some surrounding countries possibly due to restrictive use of antimicrobials [10–12]. The advised treatment in the Netherlands consists of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI)-triple therapy for 7 days without prior susceptibility testing. An increase of resistance rates to antimicrobial agents is however expected because increasing number of patients treated and increasing consumption of antibiotics, in particular macrolides, was observed in recent years [13].

The aim of the present study was firstly, to determine the efficacy of 7-day PPI-triple therapy for H. pylori in a well-defined group of patients with a rheumatic disease and serologic evidence of H. pylori infection who were on long-term NSAID therapy and secondly, to get insight in the prevalence of antibiotic resistance of H. pylori in the studied population.

Methods

This study was part of a placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial of which the clinical results have been described elsewhere [14], wherein we described that H. pylori eradication has no beneficial effect on the incidence of gastroduodenal ulcers or occurrence of dyspepsia in patients on long-term NSAID treatment. Between May 2000 and June 2002, patients were recruited from eight rheumatology outpatient departments in six cities in the Netherlands. Patients with a rheumatic disease were eligible for inclusion if they were between 40 and 80 years of age, were positive for H. pylori on serological testing and were on long-term NSAID treatment. Forty-eight percent used a gastroprotective drug (7% H2 receptor antagonists [H2RA], 37% proton pump inhibitors [PPI], 7% misoprostol, 3% used a combination of these). Exclusion criteria were previous eradication therapy for H. pylori, known allergy for the study medication or presence of severe concomitant disease.

Serologic testing for H. pylori IgG-antibodies was performed with a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Pyloriset® new EIA-G, Orion Diagnostica, Espoo, Finland) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A serum sample was considered positive for IgG antibodies to H. pylori if the test result was ≥250 International Units (IU). This assay has been assessed, in a population similar to the population in the presented trial, and has proven a sensitivity and specificity in the Netherlands of 98–100% and 79–85%, even in patients on acid suppressive therapy [15–17]. The study protocol was approved by research and medical ethics committees of all participating centers and all patients gave written informed consent.

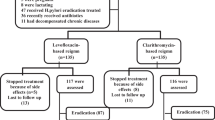

After stratification by concurrent use of gastroprotective agents (proton pump inhibitors, H2 receptor antagonists or misoprostol, but not prokinetics, or antacids), patients were randomly assigned to receive either H. pylori eradication therapy with omeprazole 20 mg, amoxicillin 1000 mg, and clarithromycin 500 mg (OAC) twice daily for 7 days or placebo. Patients with an allergy for amoxicillin were treated with omeprazole 20 mg, metronidazole 500 mg and clarithromycin 250 mg (OMC) or placebo therapy twice daily for one week in a distinct stratum. All study personnel and participants were blinded to treatment assignment for the duration of the study. The study protocol was approved by research and medical ethics committees of all participating centres and all patients gave written informed consent.

At the 2-week follow-up visit, unused study medication was returned and remaining tablets were counted in order to check compliance. Patients were considered to be noncompliant if ≤6 days (85%) of study medication were used. Three months after baseline, and additionally if clinically indicated, patients underwent endoscopy of the upper gastrointestinal tract. A total of eight biopsies were taken during each endoscopy. Four samples, two from the antrum and two from the corpus were used for histology. All biopsies were stained with haematoxylin-eosin. The slides were scored independently by an experienced gastrointestinal pathologist and the investigator (HdL), blinded to treatment assignment and clinical data, according to the updated Sydney classification [18]. In case of discrepant results, the specimen was discussed until agreement was reached. The remaining four biopsies were sent to a microbiological laboratory for culture and storage at –70°C. A patient was considered H. pylori-negative when histology as well as culture was negative. All isolated strains were assessed for susceptibility to clarithromycin, metronidazole, tetracycline and amoxicillin at the central laboratory.

Both biopsy specimens of corpus and antrum were streaked on Columbia agar (CA) (Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, MD, USA) with 10% lysed horse blood (Bio Trading, Mijdrecht, the Netherlands), referred to as Columbia agar plates, and on CA with H. pylori selective supplement (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK). Plates were incubated for 72 h at 37°C in a micro-aerophilic atmosphere (5% O2, 10% CO2, 85% N2). Identification was carried out by Gram’s stain morphology, catalase, oxidase, and urea hydrolysis measurements.

Inocula were prepared from an H. pylori culture grown on CA plates. MICs of metronidazole, clarithromycin, tetracycline and amoxicillin were determined by E-test (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) on CA plates essentially as described by Glupczynski et al. [19]. CA plates were inoculated with a bacterial suspension with a turbidity of a 3 McFarland standard (2 × 108 CFU/mL ). CLSI (tentative) breakpoints 2009 for susceptibility (S) and resistance (R) were applied (metronidazole MIC ≤ 8 mg/l (S) and ≥16 mg/l (R), amoxicillin MIC ≤ 0.5 mg/l (S) and ≥ 2 mg/l (R); tetracycline MIC ≤ 2 mg/l (S) and ≥ 8 mg/l (R), and clarithromycin MIC ≤ 0.25 mg/l (S) and ≥ 1 mg/l (R)) [20].

Measurements with a Gaussian distribution were expressed at baseline as mean and SD, and measures with a non-Gaussian distribution were expressed as the median and interquartile range (IQR; expressed as the net result of 75th percentile–25th percentile). An additional analysis compared outcomes (presence of H. pylori after H. pylori eradication therapy or placebo) between stratum (patients on gastroprotective drugs (n = 165) and not on gastroprotective drugs (n = 182) by computing the homogeneity of the common odds ratio. SPSS software (version 17.0.0) was used to perform these analyses. Differences in the proportions of patients with susceptible and resistant H. pylori strains and for compliant and non-compliant patients were analyzed with 95% confidence interval using the Confidence Interval Analysis (CIA) software for Windows (version 2.2.0). The level of significance was set at p < 0.05, two sided.

Results

A total of 347 patients consented to be randomly assigned to eradication therapy (172 patients) or placebo (175 patients). Anti-H. pylori IgG antibodies were present in all patients (median titre 1689 [IQR 700-3732]). The treatment groups were similar in terms of demographic, rheumatic disease, NSAID and other drug use. Our eligibility criteria resulted in a study group with mainly inflammatory rheumatic diseases (rheumatoid arthritis 61%, spondylarthropathy 8%, psoriatic arthritis 7%, osteoarthritis 9%, other 15%). The most commonly used NSAIDs were diclofenac (29%), naproxen (18%), and ibuprofen (13%), most at full therapeutic doses (median relative daily dose 1 [IQR 0.5–1]). The mean age was 60 years (SD 10), 61% was female. Twenty-two patients had a known allergy for amoxicillin and received metronidazole instead (10 patients) or placebo (12 patients).

Of these 347 patients, data on culture and histology of 304 patients were available (Table 1). In two cases only culture data were available and in one case only histology result was available; all three cases met the criteria for H. pylori-positivity and were found in the placebo group, but for clarity purposes were left out of Table 1. A total of 32 patients (with no significant differences between eradication and placebo groups) refused the 3-month endoscopy, withdrew informed consent, or could not undergo endoscopy because of adverse events. Seven patients used anticoagulant therapy ruling out biopsy sampling according the protocol, and in one patient no biopsy specimens could be obtained because of discomfort requiring early completion of the procedure.

At follow-up after 3 months, 79% (120 /152; 95% CI 72–85%) of the patients in the placebo group were H. pylori-positive by histology or culture of biopsy specimen. In the eradication group, this number was 13% (20/152; 95% CI 9–20%) (Table 1).

Patients in the placebo group who were H. pylori negative at 3 months as assessed by culture and histology had significantly lower titers of H. pylori anti IgG antibodies at baseline than those who were H. pylori culture- and or histology-positive (mean difference −1582, 95% CI −2637 to −527, p = 0.004). There were no differences between strata according to the use of gastroprotective drugs for the presence of H. pylori by culture and or histology (p = 0.454).

Compliance was 89% in patients in the eradication group and 98% in the placebo group with the assigned regimen (p < 0.001). In the eradication group, H. pylori could not be demonstrated in 91% of patients with full compliance (n = 136). In patients who did not take all 7 days of eradication therapy (n = 16), H. pylori was found in 50% (difference of 41%; 95% CI 18–63%). No differences were found in the placebo group.

Antibiotic resistance rates

A total of 105 clinical isolates of H. pylori were available for susceptibility testing (one isolate per patient; 95 isolates from the placebo group, ten from the eradication group) from the six participating laboratories in the Netherlands. The rates of resistance are summarized in Table 2.

In the placebo group (n = 95), resistance was found in 4% (4/95) to clarithromycin (MIC ≥1 mg/l), in 1% (1/95) and 2% (2/95) intermediate susceptibility to amoxicillin (MIC 1 mg/l) and tetracycline (MIC 4 mg/l), respectively, and in 19% (18/95) resistance to metronidazole.

Amongst these 95 isolates two were resistant to metronidazole in combination with intermediate susceptible to tetracycline, and one strain was resistant to metronidazole and clarithromycin. The placebo group had an MIC90 for clarithromycin of 0.085 mg/l, for metronidazole >256 mg/l, for tetracycline 0.341 mg/l and for amoxicillin 0.16 mg/l. One H. pylori strain was resistant to clarithromycin and metronidazole, and intermediate susceptible to tetracycline and amoxicillin. No difference was found in H. pylori resistance rates between men and women (P = 0.217) or between patients who used gastroprotective agents and who those did not (p = 0.25). In the eradication group, two strains were resistant to clarithromycin and three to metronidazole. No strains were resistant to tetracycline or amoxicillin.

Conclusion and discussion

We report the results of a study on the efficacy of a test and treat strategy for H. pylori in rheumatology patients of the Netherlands who were positive for anti-H. pylori IgG-antibodies. The main findings in the studied patient population were: (1) a 7-day PPI-triple eradication therapy either with clarithromycin or metronidazole was efficacious with eradication rates of 87% (95% CI 80–91%) without prior testing for susceptibility of the infecting strain; (2) in 21% of the patients in the placebo group, the positive H. pylori serology test could not be confirmed by positive culture or histology; (3) compliance was an important factor for successful eradication of H. pylori; and (4) prevalence of antibiotic resistance in H. pylori was low.

The main reason for not performing endoscopy at baseline was that this was not feasible in everyday rheumatology practice; therefore, serology was done to test for H. pylori. The reliability of serological kits for H. pylori infection has been widely confirmed [21], contributing to the reputation of serology as a simple, minimally invasive and inexpensive diagnostic and screening test. The best available serology test at the time of the study was the Pyloriset® an EIA-G from Orion Diagnostica, Espoo, Finland, with a specificity of 79–91% as assessed in previous studies in the Netherlands, including patients on acid suppressive therapy [22–24]. This specificity correlates well with our finding that in the placebo group, H. pylori could not be confirmed by culture or histology in 21% of the IgG positive patients. PPI usage (in this study 37% of the population) can result in false negative invasive and non-invasive diagnostic tests, such as culture, histology and 13-C urea breath, and should be stopped two weeks before testing [25]. This does not apply for serology. 13-C urea breath tests have better accuracy (>90%), but the serology test used in this study was less expensive and in all study centres easily available [26]. On the other hand, we must not overlook that conditions during transport of biopsies are critical for successful isolation of H. pylori. Possibly, the antibacterial effect of NSAIDs, as has been suggested in in vitro studies, might also partly explain a false positive rate of serology of 21% [27–29]. However, in a randomized clinical trial of 122 patients, aspirin in combination with a standard 7-day course OAC eradication was not significantly different compared to the standard therapy [29]. Based on culture and histology findings we conclude that one fifth of our patients were treated superfluously, with possible risk of side-effects of the eradication medication. Fortunately, both regimens were generally well tolerated [14].

Resistance to antibiotics in H. pylori is of particular concern because it is one of the major determinants in the failure of eradication regimens. Resistance rates for metronidazole and clarithromycin found in this study were similar as previously observed in other studies in the Netherlands in the years 1997–98 [10] and 1997–2002 [11, 12, 30, 31]. To our knowledge, there are no recent data available on H. pylori antibiotic primary resistance rates in the Netherlands [32]. In addition, in this study, compliance played a crucial role in success of eradication of H. pylori, i.e., treatment failure was as high as 50% in the non compliant group of patients. Possibly, the high number of tablets that has to be consumed during H. pylori eradication therapy is a contributing factor for non-compliance in this group of elderly patients who were also on other medications.

In conclusion, serology driven test and treat strategy eradication of H. pylori with a 7-day PPI-triple therapy is successful in the majority of patients. Success of eradication is, also in this group of rheumatology patients, to a great extent determined by compliance.

References

Kuipers EJ (1997) Helicobacter pylori and the risk and management of associated diseases: gastritis, ulcer disease, atrophic gastritis and gastric cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 11(Suppl 1):71–88

Chan FK, Sung JJ, Chung SC, To KF, Yung MY, Leung VK, Lee YT, Chan CS, Li EK, Woo J (1997) Randomised trial of eradication of Helicobacter pylori before non- steroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy to prevent peptic ulcers. Lancet 350:975–979

Chan FK, To KF, Wu JC, Yung MY, Leung WK, Kwok T, Hui Y, Chan HL, Chan CS, Hui E, Woo J, Sung JJ (2002) Eradication of Helicobacter pylori and risk of peptic ulcers in patients starting long-term treatment with non-steroidal anti- inflammatory drugs: a randomised trial. Lancet 359:9–13

Labenz J, Blum AL, Bolten WW, Dragosics B, Rosch W, Stolte M, Koelz HR (2002) Primary prevention of diclofenac associated ulcers and dyspepsia by omeprazole or triple therapy in Helicobacter pylori positive patients: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled, clinical trial. Gut 51:329–335

Moayyedi P, Soo S, Deeks J, Delaney B, Harris A, Innes M, Oakes R, Wilson S, Roalfe A, Bennett C, Forman D (2005) Eradication of Helicobacter pylori for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD002096

Kiltz U, Zochling J, Schmidt WE, Braun J (2008) Use of NSAIDs and infection with Helicobacter pylori—what does the rheumatologist need to know? Rheumatology (Oxford) 47:1342–1347

Kwaliteitsinstituut voor de Gezondheidszorg CBO (2003) Richtlijn NSAID-gebruik en preventie van maagschade. http://www.cbo.nl. Accessed 24 January 2011

Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain C, Bazzoli F, El-Omar E, Graham D, Hunt R, Rokkas T, Vakil N, Kuipers EJ (2007) Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht III Consensus Report. Gut 56:772–781

Chey WD, Wong BC (2007) American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol 102:1808–1825

Debets-Ossenkopp YJ, Herscheid AJ, Pot RG, Kuipers EJ, Kusters JG, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM (1999) Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori resistance to metronidazole, clarithromycin, amoxycillin, tetracycline and trovafloxacin in the Netherlands. J Antimicrob Chemother 43:511–515

van der Wouden EJ, van Zwet AA, Vosmaer GD, Oom JA, Jong de A, Kleibeuker JH (1997) Rapid increase in the prevalence of metronidazole-resistant Helicobacter pylori in the Netherlands. Emerg Infect Dis 3:385–389

Janssen MJ, Hendrikse L, de Boer SY, Bosboom R, de Boer WA, Laheij RJ, Jansen JB (2006) Helicobacter pylori antibiotic resistance in a Dutch region: trends over time. Neth J Med 64:191–195

SWAB (2006) NethMap 2005—Consumption of antimicrobial agents and antimicrobial resistance among medically important bacteria in the Netherlands. www.swab.nl. Accessed 24 January 2011

de LeesT HT, Steen KS, Lems WF, Bijlsma JW, van de Laar MA, Huisman AM, Vonkeman HE, Houben HH, Kadir SW, Kostense PJ, van Tulder MW, Kuipers EJ, Boers M, Dijkmans BA (2007) Eradication of Helicobacter pylori does not reduce the incidence of gastroduodenal ulcers in patients on long-term NSAID treatment: double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Helicobacter 12:477–485

Lerang F, Moum B, Mowinckel P, Haug JB, Ragnhildstveit E, Berge T, Bjorneklett A (1998) Accuracy of seven different tests for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection and the impact of H2-receptor antagonists on test results. Scand J Gastroenterol 33:364–369

Meijer BC, Thijs JC, Kleibeuker JH, van Zwet AA, Berrelkamp RJ (1997) Evaluation of eight enzyme immunoassays for detection of immunoglobulin G against Helicobacter pylori. J Clin Microbiol 35:292–294

van de Wouw BA, de Boer WA, Jansz AR, Roymans RT, Staals AP (1996) Comparison of three commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays and biopsy-dependent diagnosis for detecting Helicobacter pylori infection. J Clin Microbiol 34:94–97

Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P (1996) Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol 20:1161–1181

Glupczynski Y, Labbe M, Hansen W, Crokaert F, Yourassowsky E (1991) Evaluation of the E test for quantitative antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Helicobacter pylori. J Clin Microbiol 29:2072–2075

National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (2009) Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 19th informational supplement. CLSI 29:M100–S19

Monteiro L, Oleastro M, Lehours P, Megraud F (2009) Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter 14(Suppl 1):8–14

Lerang F, Moum B, Mowinckel P, Haug JB, Ragnhildstveit E, Berge T, Bjorneklett A (1998) Accuracy of seven different tests for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection and the impact of H2-receptor antagonists on test results. Scand J Gastroenterol 33:364–369

Meijer BC, Thijs JC, Kleibeuker JH, van Zwet AA, Berrelkamp RJ (1997) Evaluation of eight enzyme immunoassays for detection of immunoglobulin G against Helicobacter pylori. J Clin Microbiol 35:292–294

van de Wouw BA, de Boer WA, Jansz AR, Roymans RT, Staals AP (1996) Comparison of three commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays and biopsy-dependent diagnosis for detecting Helicobacter pylori infection. J Clin Microbiol 34:94–97

Kokkola A, Rautelin H, Puolakkainen P, Sipponen P, Farkkila M, Haapiainen R, Kosunen TU (2000) Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with atrophic gastritis: comparison of histology, 13 C-urea breath test, and serology. Scand J Gastroenterol 35:138–141

Lindsetmo RO, Johnsen R, Eide TJ, Gutteberg T, Husum HH, Revhaug A (2008) Accuracy of Helicobacter pylori serology in two peptic ulcer populations and in healthy controls. World J Gastroenterol 14:5039–5045

Gu Q, Xia HH, Wang WH, Wang JD, Wong WM, Chan AO, Yuen MF, Lam SK, Cheung HK, Liu XG, Wong BC (2004) Effect of cyclo-oxygenase inhibitors on Helicobacter pylori susceptibility to metronidazole and clarithromycin. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 20:675–681

Wang WH, Wong WM, Dailidiene D, Berg DE, Gu Q, Lai KC, Lam SK, Wong BC (2003) Aspirin inhibits the growth of Helicobacter pylori and enhances its susceptibility to antimicrobial agents. Gut 52:490–495

Park SH, Park DI, Kim SH, Kim HJ, Cho YK, Sung IK, Sohn CI, Jeon WK, Kim BI, Keum DK (2005) Effect of high-dose aspirin on Helicobacter pylori eradications. Dig Dis Sci 50:626–629

de Boer WA (1997) Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Review of diagnostic techniques and recommendations for their use in different clinical settings. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl 223:35–42

Thijs JC, van Zwet AA, Thijs WJ, Oey HB, Karrenbeld A, Stellaard F, Luijt DS, Meyer BC, Kleibeuker JH (1996) Diagnostic tests for Helicobacter pylori: a prospective evaluation of their accuracy, without selecting a single test as the gold standard. Am J Gastroenterol 91:2125–2129

Megraud F (2004) H. pylori antibiotic resistance: prevalence, importance, and advances in testing. Gut 53:1374–1384

Acknowledgements

We thank the nursing staff members, the medical staff members, and all other personnel who cooperated in this study of all contributing centres for their generous support and invaluable contribution. We would like to thank all laboratory assistants and other members of staff of the medical microbiology laboratories for collecting the strains and especially the VU University Medical Center Amsterdam lab for performing the E-tests.

Conflict of interest statement

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

de Leest, H.T.J.I., Steen, K.S.S., Lems, W.F. et al. Efficacy of serology driven “test and treat strategy” for eradication of H. pylori in patients with rheumatic disease in the Netherlands. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 30, 903–908 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-011-1174-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-011-1174-5