Abstract

Introduction

A recent interesting field of application of telemedicine/e-health involved smartphone apps. Although research on mHealth began in 2014, there are still few studies using these technologies in healthy elderly and in neurodegenerative disorders. Thus, the aim of the present review was to summarize current evidence on the usability and effectiveness of the use of mHealth in older adults and patients with neurodegenerative disorders.

Methods

This review was conducted by searching for recent peer-reviewed articles published between June 1, 2010 and March 2023 using the following databases: Pubmed, Embase, Cochrane Database, and Web of Science. After duplicate removal, abstract and title screening, 25 articles were included in the full-text assessment.

Results

Ten articles assessed the acceptance and usability, and 15 articles evaluated the efficacy of e-health in both older individuals and patients with neurodegenerative disorders. The majority of studies reported that mHealth training was well accepted by the users, and was able to stimulate cognitive abilities, such as processing speed, prospective and episodic memory, and executive functioning, making smartphones and tablets valuable tools to enhance cognitive performances. However, the studies are mainly case series, case–control, and in general small-scale studies and often without follow-up, and only a few RCTs have been published to date.

Conclusions

Despite the great attention paid to mHealth in recent years, the evidence in the literature on their effectiveness is scarce and not comparable. Longitudinal RCTs are needed to evaluate the efficacy of mHealth cognitive rehabilitation in the elderly and in patients with neurodegenerative disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 2021, in Europe, the prevalence of people aged more than 65 years was around 20.8% [1], and the percentage is expected to increase reaching 28.1% by 2050 [2]. The constant aging of the population is determining an increasing incidence of age-related neurodegenerative disorders, characterized by a cognitive decline (i.e., Parkinson’s disease—PD and Alzheimer’s disease—AD). Thus, the need to adapt the healthcare system to the multiple emerging needs, to improve assistance and guarantee the continuity of care is evident [3].

Moreover, during the SARS-COV-2 pandemic, the possibility of using innovative technologies to provide healthcare services at home has been emphasized [4,5,6]. In particular, telemedicine allowed the continuity of care and territorial assistance, without the physical presence of the therapist/clinician and the overload of hospitalized healthcare facilities, also favoring the reduction of the costs of the National Health Service [7, 8]. A recent interesting field of application of telemedicine/e-health involved smartphone apps. Hence, recent evidence has highlighted that mHealth through smartphones and tablets can be a useful tool for implementing effective and economical healthcare interventions, especially in the field of telecognitive rehabilitation. In fact, the devices have multiple functionalities, such as sensors, internet access, geolocation data, notifications, and clinical apps [9]. Furthermore, smartphones/tablets can provide support comparable to dedicated medical devices, without the burden and embarrassment of assistive devices [10]. However, despite the high diffusion of these technologies, their use in clinical practice is still poor [11]. Although research on mHealth began in 2014, there are still few studies using these technologies in healthy elderly and in neurological populations [12,13,14].

Indeed, it has been shown that the use of some smartphone apps may improve patient’s health, due to the use of gamification, colorful esthetics, point systems, social competitions (e.g., leaderboard), avatars, game rewards, story missions, which involve the user and improve physical activity [15, 16].

Considering that the interest in using the app in cognitive assessment and rehabilitation is growing [17,18,19,20], the aim of the present review was to summarize current evidence on the usability and effectiveness of the use of mHealth in older adults and in patients with neurodegenerative disorders.

Search strategy

This review was conducted by searching for recent peer-reviewed articles published between June 1, 2010 and March 2023 using the following databases: Pubmed, Embase, Cochrane Database, and Web of Science. The goal of the research strategy was to track progress in using mHealth for cognitive domains in older adults with and without neurodegenerative disease. To this end, the comprehensive search was conducted using the following terms: “Cognitive Rehabilitation” AND “Smartphone” OR “Mobile App”; AND/OR “older adults” and “neurodegenerative disease.”

Inclusion criteria were (i) study participants aged older than 60, (ii) mHealth approach applied to cognitive rehabilitation, (iii) English language, and (v) published in a peer-reviewed journal. We excluded articles describing theoretical models, methodological approaches, algorithms, basic technical descriptions, and validation of experimental devices that do not provide a clear translation into clinical practice. In addition, we excluded (i) animal studies, (ii) studies focusing only on other innovative approaches (such as exergaming, or serious games without smartphones or tablets), or (iii) on assessment or monitoring.

Titles and abstracts were screened independently. Relevant articles were then fully assessed. Disagreements over the article selection have been solved by discussion and with the supervision of a senior researcher.

The list of articles was then refined for relevance, revised, and summarized, with the key themes identified from the summary based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria. The following information was considered: authors, year and type of publication (e.g., clinical trials, pilot study), characteristics of the participants involved in the study, and purpose of the study.

Results

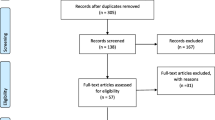

The database search produced a total of 400 titles. After duplicate removal and abstract and title screening, 25 articles were included in the full-text assessment. A flowchart of study selection is presented in Fig. 1. The main findings of the selected articles are reported in Table 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new synthematic reviews which included searches of databases and registers only. From: Page MJ, Mckenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffman TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021; 372:n71 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Acceptance and usability

Ten articles were included: 8 articles enrolling healthy elderly [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31] and 2 articles enrolling patients with neurodegenerative disorders (1 article assessing elderly with cognitive impairment [32], and 1 article assessing patients with Parkinson’s disease-PD [14]). Out of these, only the study performed b Vaportzis et al. [21], enrolling 43 seniors and reporting a good acceptance and usefulness of tablet training was an RCT. However, data on “familiarity” with smartphones and tablets remains controversial [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. Heins et al. carried out a study on 30 elderly patients, reporting that the use of technology was “viewed positively” since it helped maintain independence and quality of life [22]. Moreover, older individuals without cognitive decline showed interest in using their smartphones/tablets as a cognitive aid (e.g., reminders, alarm clocks, calendars). In addition, patients with cognitive impairment were found to have adequate acceptance and usability of devices to facilitate cognitive functioning [14, 31]. On the contrary, other studies have pointed out that younger patients had better outcomes through the use of mHealth devices than older ones [25, 26], probably due to a lack of confidence in electronic devices. The characteristics of some devices, such as internet signal problems and poorly understood interface, can create difficulties of use in the elderly, especially with cognitive deterioration. Indeed, in studies performing a training section before proposing the use of devices for cognitive support-rehabilitation, a good acceptance and usability of smartphones, and even more tablets, were reported [24, 27,28,29,30,31]. Bier et al. found that subjects with and without cognitive impairment had generalized the skills learned during training interventions to other smartphone and tablet functions, using other apps in daily life [31]. Confirming this data, Imbeault et al. reported that cognitively impaired subjects, in addition to the cognitive stimulation app, installed other apps such as diaries, or recipe apps to improve self-esteem [25]. Furthermore, we previously reported good feasibility and usability of a 6-week cognitive rehabilitation protocol based on the non-immersive virtual reality telecognitive app in non-demented PD patients [14].

Effectiveness of telerehabilitation via mHealth in the elderly

Eight articles were included, of which 2 RCT studies: Vaportzis et al. [21] reported that table training improved processing speed; Jang et al. enrolled 389 non-demented elderly volunteers and reported that home cognitive training via smartphone improved cognitive performances in terms of global cognitive functioning, language, and memory [33]. In a study enrolling 30 elderly individuals, Heintz et al. reported that participation in engaging activities characterized by new learning promoted the improvement of various cognitive skills, such as memory and executive functioning [22]. Xavier et al. in a longitudinal study enrolling more than 6400 elderly individuals demonstrated that increased Internet/email use was associated with significant improvement in memory performances [34]. Other studies have shown that mHealth enables improvements in executive functioning, such as processing speed and mental flexibility, in individuals with and without dementia. In particular, Chan et al. [27] conducted a study on 18 elderly individuals with no computer knowledge, reporting that, after training on tablet use, an improvement in episodic memory and processing speed was observed. Confirming these data, Yuan et al. noted that older adults without cognitive impairment through smartphone use showed more significant improvements in all cognitive domains, especially executive functions, than non-smartphone users [35]. Moreover, Tun and Lachman in a study of 2671 adults demonstrated that computer use can stimulate executive functions, especially the ability to switch attention and alternate attention [36]. Similarly, Kesse-Guyot et al. in a longitudinal cohort study found that older people using mHealth devices showed increases in episodic memory and executive function [37]. Furthermore, it has been observed that the knowledge acquired through mHealth training can be maintained for a long time, both in subjects with and without cognitive impairment [38,39,40,41,42]. Interestingly, the Intelligent Systems for Assessing Aging Change study on longitudinal aging has shown that the reduced use of technologies (PCs, tablets, smartphones) was associated with a smaller hippocampal volume and worse performance on memory and functioning executive in older adults with cognitive impairment [38].

Effectiveness of telerehabilitation via mHealth in patients with neurodegenerative disorders

Seven articles [43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50], including 2 RCT studies [43, 44], were included. Scullin et al. sin a study on 52 elderly people with mild dementia reported that smartphone training could stimulate memory, especially prospective memory, by learning new strategies [43]. Kraepelien et al. enrolled 77 PD patients and pointed out that smartphone training was helpful as an adjunct to standard medical treatment to improve cognitive functioning [44]. Indeed, it has been shown that mHealth training could have better cognitive outcomes from using smartphones and tablets [43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50]. Wu et al. in a study of elderly people with MCI observed that the control group, who had not used technologies, presented a reduction of global cognitive functioning, processing speed, short-term memory, and executive function [45]. Indeed, Aghanavesi et al. in a study on PD patients demonstrated that through the use of smartphones, it was possible to effectively intervene in cognitive skills [46]. These findings were also supported by Nicosia et al. [47]. The authors conducted a study on 268 cognitively normal seniors (aged 65–97 years) and 22 individuals with mild dementia showing that smartphones have the potential to intervene in the first phases of AD improving short-term memory, processing speed, and working memory [47]. These results were confirmed by El Haj et al. who highlighted the positive effect of using smartphone-based calendars on prospective memory in AD [49]. Similar findings were reported by Pang and Kim, performing a study on smartphone-based calendar training and walking exercise regimen in 42 postmenopausal women with subjective cognitive decline [50].

Discussion

Several studies supported the feasibility and efficacy of mHealth in both older individuals [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31, 33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42] and patients with neurodegenerative disorders [32, 43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. Moreover, studies reported that the use of mHealth training was able to stimulate cognitive abilities, such as processing speed, prospective and episodic memory, and executive functioning [21, 43,44,45,46,47,48,49] making smartphones and tablets valuable tools to enhance cognitive performances.

Some authors have shown that the use of mHealth could improve cognitive abilities and allow the generalization of outcomes in daily life, even in the presence of neurodegenerative disorders [19, 20, 31].

Unfortunately, it should be noted that, although the growing interest in this topic, literature data on the use of mHealth in older adults with or without neurodegenerative disorders is still scarce. It should be noted that the majority of selected studies were case–control carried out on small sample and that methodological differences such as the study population (healthy elderly versus cognitively impaired), and type of apps do not allow the comparison across the studies. Furthermore, few RCTs have been performed—in fact, to the best of our knowledge, only 2 RCTs on the effectiveness of smartphone training on older adults, and 2 RCTs related to the efficacy of smartphone tools in neurodegenerative disorders are available [28, 43,44,45]. However, literature data suggest that it would be useful to carry out specific training to increase the use of technologies, favor the effects of cognitive rehabilitation in older individuals with and without cognitive decline [28, 43,44,45], improve “familiarity” with technological tools [48], reducing anxiety about technology or technophobia [25].

In conclusion, the present review underlines that despite the great attention paid to mHealth in recent years, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic. Longitudinal RCTs are needed to evaluate the efficacy of mHealth cognitive rehabilitation in healthy elderly and in patients with neurodegenerative disorders.

Data availability

Data will be available on request to the corresponding author.

References

De Luca R, Torrisi M, Bramanti A, Maggio MG, Anchesi S, Andaloro A, Caliri S, De Cola MC, Calabrò RS (2021) A multidisciplinary Telehealth approach for community-dwelling older adults. Geriatr Nurs 42(3):635–642

Eurostat (2022) Population structure and aging. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Population_structure_and_agein. Accessed Feb 2023

Panaszek B, Machaj Z, Bogacka E, Lindner K (2009) Chronic disease in the older people: a vital rationale for the revival of internal medicine. Pol Arch Med Wewn 119(4):248–254

Zhou X, Snoswell CL, Harding LE, Bambling M, Edirippulige S, Bai X, Smith AC (2020) The role of telehealth in reducing the mental health burden from COVID-19. Telemed J E Health 26(4):377–379

Maggio MG, De Luca R, Manuli A, Calabrò RS (2020) The five ‘W’ of cognitive telerehabilitation in the Covid-19 era. Expert Rev Med Devices 17(6):473–475

Calabrò RS, Maggio MG (2020) Telepsychology: a new way to deal with relational problems associated with the COVID-19 epidemic. Acta Biomed 91(4):e2020140

Weinstein RS, Lopez AM, Joseph BA et al (2014) Telemedicine, telehealth, and mobile health applications that work: opportunities and barriers. Am J Med 127:183–187

Bramanti A, Calabrò RS (2018) Telemedicine in neurology: where are we going? Eur J Neurol 25:e6

Putzer GJ, Park Y (2012) Are physicians likely to adopt emerging mobile technologies? Attitudes and innovation factors affecting smartphone use in the Southeastern United States. Persp Health Inf Manag 9:1b

Shinohara K, Wobbrock JO (2011) In the shadow of misperception: assistive technology use and social interactions. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems, pp 705–714

De Joode E, van Heugten C, Verhey F, van Boxtel M (2010) Efficacy and usability of assistive technology for patients with cognitive deficits: a systematic review. Clinical Rehab 24(8):701–714

Kim BY, Lee J (2017) Smart devices for older adults managing chronic disease: a scoping review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 5(5):e69

Klimova (2017) Mobile phones and/or smartphones and their use in the management of dementia–findings from the research studies. In: Digital nations–smart cities, innovation, and sustainability: 16th IFIP WG 6.11 conference on e-business, e services, and e-society, I3E 2017, Proceeding 16. Springer International Publishing, Delhi, India, pp 33–37

Maggio MG, Luca A, D’Agate C, Italia M, Calabrò RS, Nicoletti A (2022) Feasibility and usability of a non-immersive virtual reality tele-cognitive app in cognitive rehabilitation of patients affected by Parkinson’s disease. Psychogeriatrics 22(6):775–779

Kirk MA, Amiri M, Pirbaglou M, Ritvo P (2019) Wearable technology and physical activity behavior change in adults with chronic cardiometabolic disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Health Promot 33(5):778–791

Edwards EA, Lumsden J, Rivas C, Steed L, Edwards LA, Thiyagarajan A et al (2016) Gamification for health promotion: a systematic review of behavior change techniques in smartphone apps. BMJ Open 6(10):e012447

Ellis TD, Earhart GM (2021) Digital therapeutics in Parkinson’s disease: practical applications and future potential. J Parkinsons Dis 11(s1):S95–S101

Landers MR, Ellis TD (2020) A mobile app specifically designed to facilitate exercise in Parkinson’s disease: single-cohort pilot study on feasibility, safety, and signal of efficacy. JMIR mHealth Uhealth 8:e18985

Gustavsson M, Ytterberg C, Nabsen Marwaa M, Tham K, Guidetti S (2018) Experiences of using information and communication technology within the first year after stroke - a grounded theory study. Disabil Rehabil 40(5):561–568

Kwan RYC, Cheung DSK, Kor PP (2020) The use of smartphones for wayfinding by people with mild dementia. Dementia 19(3):721–735

Vaportzis E, Martin M, Gow AJ (2017) A tablet for healthy aging: the effect of a tablet computer training intervention on cognitive abilities in older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 25(8):841–851

Heinz M, Martin P, Margrett JA, Yearns M, Franke W, Yang HI, Wong J, Chang CK (2013) Perceptions of technology among older adults. J Gerontol Nurs 39(1):42–51

Wong D, Wang QJ, Stolwyk R, Ponsford J (2017) Do smartphones have the potential to support cognition and independence following stroke? Brain Imp 18(3):310–320

Nguyen T, Irizarry C, Garrett R, Downing A (2015) Access to mobile communications by older people. Aust J Ageing 34(2):E7–E12

Petrovčič A, Peek S, Dolničar V (2019) Predictors of seniors’ interest in assistive applications on smartphones: evidence from a population-based survey in Slovenia. Int J Env Res Public Health 16:1623

Imbeault H, Langlois F, Bocti C, Gagnon L, Bier N (2018) Can people with Alzheimer’s disease improve their day-today functioning with a tablet computer? Neurops Rehab 28(5):779–796

Chan MY, Haber S, Drew LM, Park DC (2016) Training older adults to use tablet computers: does it enhance cognitive function? Gerontologist 56(3):475–484

Vaportzis E, Clausen MG, Gow AJ (2017) Older adults perceptions of technology and barriers to interacting with tablet computers: a focus group study. Front Psychol 8:1687

Vaportzis E, Giatsi Clausen M, Gow AJ (2018) Older adults experience learning to use tablet computers: a mixed methods study. Front Psychol 9:1631

Álvarez-Dardet SM, Lara BL, Pérez-Padilla J (2020) Older adults and ICT adoption: analysis of the use and attitudes toward computers in elderly Spanish people. Comp Hum Beh 110:106377

Bier N, Paquette G, Macoir J (2018) Smartphone for smart living: using new technologies to cope with everyday limitations in semantic dementia. Neuropsych Rehab 28(5):734–754

Benge JF, Dinh KL, Logue E, Phenis R, Dasse MN, Scullin MK (2020) The smartphone in the memory clinic: a study of patient and care partner’s utilization habits. Neuropsych Rehab 30(1):101–115

Jang H, Yeo M, Cho J, Kim S, Chin J, Kim HJ, Seo SW, Na DL (2021) Effects of smartphone application-based cognitive training at home on cognition in community-dwelling non-demented elderly individuals: a randomized controlled trial. Alzh Dem 7(1):e12209

Xavier AJ, d’Orsi E, de Oliveira CM, Orrell M, Demakakos P, Biddulph JP, Marmot MG (2014) English longitudinal study of aging: can Internet/E-mail use reduce cognitive decline? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 69(9):1117–1121

Yuan M, Chen J, Zhou Z, Yin J, Wu J, Luo M, Wang L, Fang Y (2019) Joint associations of smartphone use and gender on multidimensional cognitive health among community-dwelling older adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr 19(1):140

Tun PA, Lachman ME (2010) The association between computer use and cognition across adulthood: use it so you won’t lose it? Psychol Aging 25(3):560–568

Kesse-Guyot E, Charreire H, Andreeva VA, Touvier M, Hercberg S, Galan P, Oppert JM (2012) Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations of different sedentary behaviors with cognitive performance in older adults. PLoS ONE 7(10):e47831

Silbert LC, Dodge HH, Lahna D, Promjunyakul NO, Austin D, Mattek N, Erten-Lyons D, Kaye JA (2016) Less daily computer use is related to smaller hippocampal volumes in cognitively intact elderly. J Alzheimers Dis 52(2):713–717

Rivest J, Svoboda E, McCarthy J, Moscovitch M (2018) A case study of topographical disorientation: behavioural intervention for achieving independent navigation. Neuropsychol Rehabil 28(5):797–817

Routhier S, Macoir J, Imbeault H et al (2011) From smartphone to external semantic memory device: the use of new technologies to compensate for semantic deficits. Non-pharm Therapies Dem 2(2):81

Bier N, Brambati S, Macoir J, Paquette G, Schmitz X, Belleville S, Faucher C, Joubert S (2015) Relying on procedural memory to enhance independence in daily living activities: smartphone use in a case of semantic dementia. Neuropsychol Rehabil 25(6):913–935

Zilberman M, Benham S, Kramer P (2016) Tablet technology and occupational performance for older adults: a pilot study. Gerontechn 15(2):109–115

Scullin MK, Jones WE, Phenis R, Beevers S, Rosen S, Dinh K, Kiselica A, Keefe FJ, Benge JF (2022) Using smartphone technology to improve prospective memory functioning: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 70(2):459–469

Kraepelien M, Schibbye R, Månsson K, Sundström C, Riggare S, Andersson G, Lindefors N, Svenningsson P, Kaldo V (2020) Individually tailored internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for daily functioning in patients with Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. J Parkinsons Dis 10:653–664

Wu YH, Lewis M, Rigaud AS (2019) Cognitive function and digital device use in older adults attending a memory clinic. Ger Geriatric Med 5:2333721419844886

Aghanavesi S, Nyholm D, Senek M, Bergquist F, Memedi M (2017) A smartphone-based system to quantify dexterity in Parkinson’s disease patients. Inform Med Unlocked 9:11–17

Nicosia J, Aschenbrenner AJ, Balota DA, Sliwinski MJ, Tahan M, Adams S, Stout SS, Wilks H, Gordon BA, Benzinger TLS, Fagan AM, Xiong C, Bateman RJ, Morris JC, Hassenstab J (2022) Unsupervised high-frequency smartphone-based cognitive assessments are reliable, valid, and feasible in older adults at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 29(5):459–471

El Haj M, Moustafa AA, Gallouj K, Allain P (2021) Cuing prospective memory with smartphone-based calendars in Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 36(3):316–321

Pang Y, Kim O (2021) Effects of smartphone-based compensatory cognitive training and physical activity on cognition, depression, and self-esteem in women with subjective cognitive decline. Brain Sci 11(8):1029

Tuteja D, Arun Kumar N, Pai DS, Kunal K (2020) Effect of mobile phone usage on cognitive functions, sleep pattern, visuospatial ability in Parkinsons patients; a possible correlation with onset of clinical symptoms. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol 32(2):33–37

Acknowledgements

Dr. Maggio performed this study during her Ph.D. in Neuroscience at the University of Catania.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Catania within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Human and animal rights

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent for publication

This manuscript has been approved for publication by all authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maggio, M.G., Luca, A., Calabrò, R.S. et al. Can mobile health apps with smartphones and tablets be the new frontier of cognitive rehabilitation in older individuals? A narrative review of a growing field. Neurol Sci 45, 37–45 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-023-07045-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-023-07045-8