Abstract

Objectives

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a rare and fatal neurodegenerative disease that can overlap with pregnancy, but little is known about its clinical characteristics, course, and outcomes in this context. This systematic review aimed to synthesize the current evidence on ALS overlapping with pregnancy.

Methods

We comprehensively searched four databases on February 2, 2023, to identify case studies reporting cases of ALS overlapping with pregnancy. Joanna Brigs Institute tool was followed to assess the quality of the included studies.

Results

Twenty-six articles reporting 38 cases were identified and included in our study. Out of the 38 cases, 18 were aged < 30 years. The onset of ALS was before pregnancy in 18 cases, during pregnancy in 16 cases, and directly after pregnancy in 4 cases. ALS progression course was rapid or severe in 55% of the cases during pregnancy, and this percentage reached 61% in cases with an onset of ALS before pregnancy. While ALS progression course after pregnancy was rapid or severe in 63% and stable in 37% of the cases. Most cases (95%) were able to complete the pregnancy and gave live birth. However, preterm delivery was common. For neonates, 86% were healthy without any complications.

Conclusion

While pregnancy with ALS is likely to survive and result in giving birth to healthy infants, it could be associated with rapid or severe progression of ALS and result in a worse prognosis, highlighting the importance of close monitoring and counselling for patients and healthcare providers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a neurodegenerative disease that is rare, progressive, and ultimately fatal. It affects both the upper and lower motor neurons, leading to muscle weakness, atrophy, and paralysis over time [1]. Typically, ALS is diagnosed in middle age, with an average onset between 51 and 66 years, and is more prevalent in men than women [2]. Although ALS is uncommon in younger individuals, there have been isolated cases of ALS occurring during pregnancy [3, 4]. This overlap between ALS and pregnancy poses unique challenges, as the symptoms of ALS may worsen during pregnancy and complicate disease management. Additionally, the impact of ALS on the health of the developing fetus and pregnancy outcomes is not well understood.

The management of ALS involves a multidisciplinary approach that aims to manage symptoms, address complications, and provide supportive care to improve the quality of life of the patient [5]. This may involve a combination of medication, physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, and respiratory therapy [6]. Managing ALS during pregnancy can be particularly challenging, as pregnant women with ALS may experience worsening of symptoms or complications associated with the disease. For example, respiratory function may be compromised due to the increased metabolic demands of pregnancy, and the use of certain medications may be contraindicated during pregnancy [7]. Therefore, close monitoring and coordinated care between the patient’s healthcare providers are essential to manage the disease effectively during pregnancy and ensure the best possible outcomes for both the mother and the baby.

Due to the rarity and complexity of ALS during pregnancy, there is a need to enhance our understanding of the disease and its management in this context. This article aimed to investigate the relationship between ALS and pregnancy, the course of ALS during pregnancy, and the potential impact of ALS on pregnancy outcomes.

Methods

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) guidelines were followed during presenting this review [8].

Search strategy and inclusion criteria

On February 2, 2023, a comprehensive search was conducted on PubMed, EBSCO, Scopus, and Web of Science using the following search terms: (“Motor Neuron Disease” OR “Motor System Disease” OR “Gehrig Disease” OR “Charcot Disease” OR “Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis” OR “Guam Disease” OR “ALS”) AND (“pregnant” OR “pregnancy”). No search restrictions or filters were applied. Studies had to meet the following criteria to be included in our review: (a) be case reports or case series describing cases of ALS overlapping with pregnancy; (b) be published after 1980 to avoid outdated cases; and (c) be reported in English.

Outcomes of interest

The primary outcomes of interest in this review included the course of ALS during and after pregnancy, as well as the pregnancy and neonatal outcomes of women with ALS. The progression of ALS was assessed based on the rate of disease progression during pregnancy and after delivery, as reported in the included studies. The course of the disease was determined based on the reported changes in the patient’s functional status, clinical features, and survival during and after pregnancy. The progression of ALS was classified as stable if there was no significant change in these measures or as rapid or severe progression if there was a significant decline, while the pregnancy and neonatal outcomes of interest included gestational age at delivery, mode of delivery, neonatal birth weight and health status, and the incidence of neonatal morbidity.

Screening and data extraction

Without removing duplicates from the identified records [9], titles and abstracts were independently screened against the inclusion criteria by two authors. Then, the full texts of articles identified from that stage were retrieved and screened by a third author to make the final decision. After identifying the included articles, two authors extracted the data independently with the help of an online data form. The extracted data included: (a) study year and country; (b) age and gestational history; (c) onset of ALS; (d) course of ALS during and after pregnancy; (e) pregnancy and neonatal outcomes; and (f) quality assessment domains. Any discrepancies in screening or data extraction were resolved through discussion with a third author.

Quality assessment

The quality assessment of the included studies was performed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) tool for case reports [10]. Two authors independently assessed the quality of each study, and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a third author. The JBI tool includes specific criteria for evaluating the methodological quality of case reports and case series [10].

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

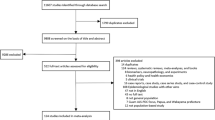

Following the search strategy, we identified 3841 articles. After applying our inclusion criteria, we identified 26 articles reporting 38 cases of ALS overlapping with pregnancy, with 18 cases occurring in women under 30 years of age [3, 4, 7, 11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. Figure 1 summarizes the selection process of the included studies. The onset of ALS was before pregnancy in 18 cases, during pregnancy in 16 cases, and directly after pregnancy in 4 cases. Out of 21 cases with reported obstetric history, 7 cases were primigravida. Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics, clinical course, and outcomes of the included studies. The quality assessment of the included studies is summarized in Table 2.

ALS course

The progression of ALS was rapid or severe in the majority of cases during pregnancy, with 17 out of 31 cases (55%) experiencing rapid or severe progression and 45% experiencing stable progression. Among cases with an onset of ALS before pregnancy, 11 out of 18 cases (61%) showed rapid or severe progression during pregnancy, while among cases with an onset of ALS during pregnancy, 6 out of 13 cases (46%) showed rapid or severe progression during pregnancy. After pregnancy, 20 out of 32 cases (63%) showed rapid or severe progression, and 37% showed stable progression of ALS. The clinical course of ALS for each case is summarized in Table 1.

Pregnancy and neonatal outcomes

Out of 37 cases, 35 (95%) were able to complete their pregnancies and give live birth, while the remaining two cases resulted in stillbirths [23, 24]. However, only 33% (8 out of 24) of these completed pregnancies reached 38 weeks. The delivery method was cesarean in 10 cases, vaginal in 9 cases, and not reported in the other cases (Table 1). For neonatal outcomes, most cases (25 out of 29) resulted in normal healthy infants without complications. In the other four cases, three infants showed transient complications after delivery [4, 20, 29], while one infant had small atrial communication and a small patent ductus arteriosus [31].

Discussion

Main findings

The aim of this systematic review was to investigate the impact of pregnancy on the progression of ALS and to examine neonatal and pregnancy outcomes in affected patients. Our results support the hypothesis that pregnancy increases the potential for severe and rapid ALS progression, regardless of the timing of ALS onset in relation to pregnancy. Also, the majority of cases reviewed demonstrated that ALS had no negative impact on neonatal or pregnancy outcomes.

Interpretations

ALS is a neurodegenerative disorder which affects the motor ganglia of both upper and lower motor neurons [1]. It is more common in men, and its incidence is increased after the fifth decade [2, 34]. Therefore, it rarely affects women in their child bearing periods. This can explain why ALS overlapping with pregnancy is very rare. To date, the exact etiology of ALS progression is still unknown; however, sex-related factors, such as hormones, may play a role in its progression. Previous animal studies showed that both estrogen and progesterone are protective against ALS progression in mice models [35]. The abrupt decrease in the levels of these hormones after delivery may explain the rapid or severe progression of ALS after pregnancy. However, this theory cannot explain the rapid progression of ALS during pregnancy when these hormones are normally elevated. In addition, a recent case control study showed that the odds of ALS were decreased in women receiving estrogen-progesterone hormone replacement therapy in the Netherlands; however, this protective effect was not observed in women in both Italy and Ireland [36]. Similarly, this protective effect could not be observed in earlier studies which enrolled postmenopausal women receiving estrogen replacement therapy [37, 38]. The conflicting results of these studies suggest that hormonal changes are not the only factor which contributes to ALS pathogenesis and progression. Genetic factors, such as mutations in vascular endothelial growth factor premotor and superoxide dismutase genes, may also contribute to the pathogenesis of ALS [25, 39]. Moreover, the inflammatory changes during pregnancy increase the oxidative stress, which further induces these genetic mutations increasing ALS susceptibility [30].

ALS primarily affects the voluntary muscles causing their progressive atrophy; however, it may affect the respiratory system which is mainly involuntary [32]. This can be attributed to the voluntary component of the diaphragm and costal muscles which can further be affected by ALS. In pregnant women, the enlarging uterus leads to upward elevation of the diaphragm and increases the risk of diaphragmatic fatigue [40]. Moreover, pregnancy, delivery, and the immediate postpartum period require an increase in respiratory work, which is normally achieved through diaphragmatic breathing [30]. Hence, respiratory muscle affection is the main concern in ALS overlapping with pregnancy [30]. The rapid deterioration of ALS progression after delivery, regardless of its onset in relation to pregnancy, may be attributed to the failure to meet the increased demand of respiratory work required during pregnancy, delivery, and the postpartum period [14]. Therefore, vaginal delivery, which requires more respiratory effort than cesarean section, is preferred only when the patients’ respiratory condition is stable. Otherwise, cesarean section is considered a safer option [14].

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first systematic review to gather the evidence from all published case studies regarding ALS overlapping with pregnancy. All included reports were peer-reviewed case studies. In addition, we excluded studies published before 1980 to avoid outdated cases. Finally, we did not only explore the impact of pregnancy on ALS progression but also explored pregnancy and neonatal outcomes in ALS with pregnancy. Nevertheless, our study is not free of limitations. Firstly, the course of ALS was primarily determined based on clinical and functional characteristics reported in the cases, rather than on objective or quantitative measures such as the Revised Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale, which were rarely reported. Secondly, the lack of genetic information in our analysis may have limited our ability to explain the progressive course of ALS, as genetic mutations may explain the ALS progressive course especially in young age [41, 42]. We also observed heterogeneity among the included studies in terms of ALS onset in relation to pregnancy and phenotypic characterization of the patients. This may have also limited the generalizability and validity of the findings. Lastly, we excluded non-English studies, which may potentially reduce the comprehensiveness of our systematic review. Together, all these limitations restrict the generalizability of our findings.

Clinical implications and recommendations

Our results suggest that respiratory support is essential to meet the increased demands during pregnancy, delivery, and even the postpartum period in ALS-affected women. This may reduce the potential risk for respiratory failure and slow ALS progression after delivery. Moreover, monitoring of respiratory functions in pregnant females with ALS is crucial, particularly during the third trimester to determine the best option for delivery. One included study reported the use of riluzole during pregnancy, which was associated with neonatal cardiac malformations [31]; however, another study showed that riluzole did not cause any maternal or fetal side effects [19]. Further studies are required to truly explore the impact of maternal use of riluzole during pregnancy on both maternal and neonatal outcomes.

Conclusion

While pregnancy with ALS is likely to survive and result in giving birth to healthy infants, it could be associated with rapid or severe progression of ALS and result in a worse prognosis, highlighting the importance of close monitoring and counselling for patients and healthcare providers. Further research is necessary to gain a better understanding of the pathophysiology and optimal management of ALS in pregnancy. Future studies should consider including genetic assessments and ALS functional scores to enhance our understanding of ALS in this context. Overall, a better understanding of ALS in pregnancy can help guide clinical decision-making and improve outcomes for both the mother and infant.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

References

Hardiman O, Al-Chalabi A, Chio A et al (2017) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Prim 3:17071. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2017.71

Longinetti E, Fang F (2019) Epidemiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: an update of recent literature. Curr Opin Neurol 32:771–776. https://doi.org/10.1097/WCO.0000000000000730

Porto LB, Berndl AML (2019) Pregnancy 5 years after onset of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis symptoms: a case report and review of the literature. J Obstet Gynaecol Canada 41:974–980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2018.09.015

Sarafov S, Doitchinova M, Karagiozova Z et al (2009) Two consecutive pregnancies in early and late stage of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 10:483–486. https://doi.org/10.3109/17482960802578365

Simmons Z (2005) Management strategies for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis from diagnosis through death. Neurologist 11:257–270. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nrl.0000178758.30374.34

Miller RG, Jackson CE, Kasarskis EJ et al (2009) Practice parameter update: the care of the patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: drug, nutritional, and respiratory therapies (an evidence-based review): report of the quality standards subcommittee of the american academy of neurology. Neurology 73:1218–1226. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bc0141

Bazán-Rodríguez L, Ruíz-Avalos JA, Bernal-López O et al (2022) FUS as a cause of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a case report in a pregnant patient. Neurocase 28:323–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/13554794.2022.2100265

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339:b2535–b2535. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535

Hamad AA (2023) Reconsidering the need for de-duplication prior to screening in systematic reviews. AlQ J Med Appl Sci 6:367–368. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8126972

Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, et al (2020) Chapter 7: systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z (Eds). JBI manual for evidence synthesis. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES20-08. Accessed 20 Jun 2023

Vincent O, Rodriguez-Ithurralde D (1995) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and pregnancy. J Neurol Sci 129:42–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-510X(95)00059-B

Wang Y, Zhang Y, Li S et al (2021) Transversus abdominis plane block provides effective and safe anesthesia in the cesarean section for an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis parturient. Medicine (Baltimore) 100:e27621. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000027621

Weiss MD, Ravits JM, Schuman N, Carter GT (2006) A4V superoxide dismutase mutation in apparently sporadic ALS resembling neuralgic amyotrophy. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 7:61–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660820500467009

Xiao W, Zhao L, Wang F et al (2017) Total intravenous anesthesia without muscle relaxant in a parturient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis undergoing cesarean section: a case report. J Clin Anesth 36:107–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinane.2016.10.009

Ali A, Mowat A, Jones N, Mustfa N (2022) A case of successful pregnancy managed in a patient living with motor neurone disease for more than 3 years. BMJ Case Rep 15:e248872. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2022-248872

Tyagi A, Sweeney BJ, Connolly S (2001) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis associated with pregnancy. Neurol India 49:413–414

Hilton DA, McLean B (2002) December 2001: rapidly progressive motor weakness, starting in pregnancy. Brain Pathol 12(267–8):269. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-3639.2002.tb01094.x

Jacka MJ, Sanderson F (1998) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis presenting during pregnancy. Anesth Analg 86:542–543. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000539-199803000-00018

Kawamichi Y, Makino Y, Matsuda Y et al (2010) Riluzole use during pregnancy in a patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a case report. J Int Med Res 38:720–726. https://doi.org/10.1177/147323001003800237

Kock-Cordeiro DBM, Brusse E, van den Biggelaar RJM et al (2018) Combined spinal-epidural anesthesia with non-invasive ventilation during cesarean delivery of a woman with a recent diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Int J Obstet Anesth 36:108–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijoa.2018.06.001

Leveck DE, Davies GA (2005) Rapid progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis presenting during pregnancy: a case report. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 27:360–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30463-7

Marsli S, Mouni F, Araqi A et al (2020) Can pregnancy decompensate an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)? Case report and review of literature. Rev Neurol (Paris) 176:216–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurol.2019.07.021

Chiò A, Calvo A, Di Vito N et al (2003) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis associated with pregnancy: report of four new cases and review of the literature. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Mot Neuron Disord 4:45–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660820310006724

Hancevic M, Bilic H, Sitas B et al (2019) Attenuation of ALS progression during pregnancy—lessons to be learned or just a coincidence? Neurol Sci 40:1275–1278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-019-03748-z

Lunetta C, Sansone VA, Penco S et al (2014) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in pregnancy is associated with a vascular endothelial growth factor promoter genotype. Eur J Neurol 21:594–598. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.12345

Lupo VR, Rusterholz JH, Reichert JA, Hanson AS (1993) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 82:682–685

Martínez HR, Marioni SS, Escamilla Ocañas CE et al (2014) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in pregnancy: clinical outcome during the post-partum period after stem cell transplantation into the frontal motor cortex. Cytotherapy 16:402–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcyt.2013.11.002

Masrori P, Ospitalieri S, Forsberg K et al (2022) Respiratory onset of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in a pregnant woman with a novel SOD1 mutation. Eur J Neurol 29:1279–1283. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.15224

Miranda J, Palacio B, Rojas-Suarez JA, Bourjeily G (2014) Long-term mechanical ventilation in a pregnant woman with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a successful outcome. Case Reports Perinat Med 3:31–34. https://doi.org/10.1515/crpm-2013-0019

Pathiraja PDM, Ranaraja SK (2020) A successful pregnancy with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2020:1–3. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/1247178

Scalco RS, Vieira MC, da Cunha Filho EV et al (2012) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and riluzole use during pregnancy: a case report. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 13:471–472. https://doi.org/10.3109/17482968.2012.673171

Sobrino-Bonilla Y (2004) Caring for a laboring women with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. MCN, Am J Matern Nurs 29(243):247. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005721-200407000-00009

Solodovnikova Y, Kobryn A, Ivaniuk A, Son A (2021) Fulminant amyotrophic lateral sclerosis manifesting in a young woman during pregnancy. Neurol Sci 42:3019–3021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-021-05175-5

Traynor BJ, Codd MB, Corr B et al (1999) Incidence and prevalence of ALS in Ireland, 1995–1997: a population-based study. Neurology 52:504–504. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.52.3.504

Trojsi F, D’Alvano G, Bonavita S, Tedeschi G (2020) Genetics and sex in the pathogenesis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS): is there a link? Int J Mol Sci 21:3647. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21103647

Rooney JPK, Visser AE, D’Ovidio F et al (2017) A case-control study of hormonal exposures as etiologic factors for ALS in women. Neurology 89:1283–1290. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000004390

Rudnicki SA (1999) Estrogen replacement therapy in women with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 169:126–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-510X(99)00234-8

Popat RA, Van Den Eeden SK, Tanner CM et al (2006) Effect of reproductive factors and postmenopausal hormone use on the risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuroepidemiology 27:117–121. https://doi.org/10.1159/000095550

Andersen PM (2000) Genetic factors in the early diagnosis of ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Mot Neuron Disord 1:S31–S42. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660820052415899

Papavramidis TS, Kotidis E, Ioannidis K et al (2011) Diaphragmatic adaptation following intra-abdominal weight charging. Obes Surg 21:1612–1616. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-010-0334-5

Picher-Martel V, Brunet F, Dupré N, Chrestian N (2020) The occurrence of FUS mutations in pediatric amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a case report and review of the literature. J Child Neurol 35:556–562. https://doi.org/10.1177/0883073820915099

Zou Z-Y, Che C-H, Feng S-Y et al (2021) Novel FUS mutation Y526F causing rapidly progressive familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Front Degener 22:73–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/21678421.2020.1797815

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hamad, A.A., Amer, B.E., AL Mawla, A.M. et al. Clinical characteristics, course, and outcomes of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis overlapping with pregnancy: a systematic review of 38 published cases. Neurol Sci 44, 4219–4231 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-023-06994-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-023-06994-4