Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to evaluate the experience with telemedicine in patients with cognitive impairments and their caregivers.

Methods

We conducted a survey-based study of patients who completed neurological consultation via video link between January and April 2022.

Results

A total of 62 eligible neurological video consultations were conducted for the following categories of patients: Alzheimer’s disease (33.87%), amnesic mild cognitive impairment (24.19%), frontotemporal dementia (17.74%), Lewy body dementia (4.84%), mixed dementia (3.23%), subjective memory disorders (12.90%), non-amnesic mild cognitive impairment (1.61%), and multiple system atrophy (1.61%).

The survey was successfully completed by 87.10% of the caregivers and directly by the patients in 12.90% of cases. Our data showed positive feedback regarding the telemedicine experience; both caregivers and patients reported that they found neurological video consultation useful (caregivers: 87.04%, ‘very useful’; patients: 87.50%, ‘very useful’) and were satisfied overall (caregivers: 90.74%, ‘very satisfied’; patients: 100%, ‘very satisfied’). Finally, all caregivers (100%) agreed that neurological video consultation was a useful tool to reduce their burden (Visual Analogue Scale mean ± SD: 8.56 ± 0.69).

Conclusions

Telemedicine is well received by patients and their caregivers. However, successful delivery incorporates support from staff and care partners to navigate technologies. The exclusion of older adults with cognitive impairment in developing telemedicine systems may further exacerbate access to care in this population. Adapting technologies to the needs of patients and their caregivers is critical for the advancement of accessible dementia care through telemedicine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has rendered older adults more vulnerable to not receiving the healthcare needed. Furthermore, it has placed those living with dementia at an even increased risk of developing other mental health symptoms due to social isolation and loneliness [1]. Indeed, as the virus spreads, it has become necessary to introduce social distancing measures, such as quarantine within urban areas, prohibition of travel to and from certain countries, and suspension of a large range of clinical activities. Elective face-to-face consultations had to be rescheduled, and the need for health care during the pandemic required telehealth solutions. National initiatives have been launched to review and update previous restrictions on telehealth practices and to expand their use as a solution for improving the care provided in the national state-funded health system [2].

Older adults were considered to be the most vulnerable portion of the population at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. This situation has raised concerns regarding the management and care of people with cognitive impairment and their caregivers. Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia can be triggered or exacerbated by several risk factors, such as social isolation, pharmacology adherence disruption, caregiver load, reduction of non-pharmacologic techniques, absence of medical assessment, and changes in home routine [2].

Telehealth has proven to be a viable alternative for providing individuals with appropriate services and care, as well as for mitigating the effects of social isolation, particularly in older patients with cognitive impairment and dementia [3, 4]. Through video consultation systems, telemedicine allows healthcare professionals to manage patients remotely and conduct follow-up and monitoring visits, enabling patients to receive continuous care support [5].

With the growing population of older adults with dementia, it is imperative to improve telemedicine systems to adapt them to their needs. To the best of our knowledge, few studies have assessed the critical issues of using neurological video consultation to deliver care to patients with cognitive impairment or dementia in the Italian public health system.

This study aimed to evaluate the experience of telemedicine in patients with cognitive deficits and their caregivers to outline new socio-health models to meet the care needs of fragile patients, as in the case of neurodegenerative diseases.

Methods

Recruitment

We conducted an institutional review board-approved survey-based study of patients who completed routine neurological consultation via video link between January 2022 and April 2022 at the Alzheimer’s Unit of the IRCCS Ca’ Granda Foundation Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico in Milan, Italy. The patients were being treated for amnesic and non-amnesic mild cognitive impairment (MCI), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Lewy body dementia (LBD), frontotemporal dementia (FTD), mixed dementia, multiple system atrophy (MSA), and subjective memory disorders. The survey was administered to the caregivers of all patients diagnosed with cognitive impairment, whereas the survey was proposed directly to those patients diagnosed with subjective memory disorders who attended video consultation without the support of a caregiver.

The extent to which the caregivers’ experienced a reduction in burden after the neurological video consultation was assessed using a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) with items rated from 0 (not at all) to 10 (complete reduction in burden).

The participants were contacted by telephone using their preferred contact phone number provided in the electronic medical record, by two psychologists within 1 week of their neurological video consultation. The interviewers were responsible for conducting the pilot test calls, making final phone calls, and recording data for analysis. The database containing the total sample was organised alphabetically according to diagnosis and divided into halves, each of which was distributed to the interviewers for the telephone survey.

The appropriate Ethics Committee reviewed and approved the distribution of the survey for this study following local legal standards and authorised the disclosure (Protocol no. 184_2021bis). Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, consent for the processing of personal data was obtained from the participants over the phone before the survey.

Survey development and structure

We created a survey based on the recommendations proposed by Langbecker et al. [6], who investigated the most common surveys and tools in remote medical research.

The survey consisted of two sections, as described in our previous study [7]. The first section was used to collect clinical and demographic data. The second section evaluated participants’ viewpoint to video consultation (defined as ‘telemedicine’) through the following constructs: ‘satisfaction’, ‘experience’, ‘technical quality’, ‘effectiveness’, ‘usefulness/perceived usefulness’, and ‘effect on interaction’ [6] (Table 1). Participants were asked to rate their agreement with multiple statements on a VAS ranging from 0 (‘strongly disagree’) to 4 (‘strongly agree’).

Statistical analysis

Responses were recorded using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the Policlinico Hospital which was also used for data entry, editing, and sorting. For all continuous variables, the mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated, and categorical data were represented as frequencies and percentages. Statistical analysis of the data was performed using TIBCO Statistica ™ software (version 13.5). Wilcoxon Rank Sum test and Chi-Square test were applied to compare, respectively, continuous and categorical variables between groups. To evaluate the correlation between the construct scores of the survey, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (r) was calculated between each construct and all others. In this study, we considered both positive and negative correlations with significance ranging from r = 0.5 to r = 0.7. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

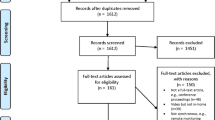

During the study period, 83 patients underwent video neurological consultations. Among them, 21 (25.30%) were excluded from the survey-based study: 19 (22.89%) chose not to participate, and 2 (2.41%) were unreachable by phone.

We collected data from 62 respondents (74.70%): 54 (65.10%) were caregivers and 8 (9.64%) were patients. No significant differences we found between the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients of caregivers and patients who responded independently to the survey with those of the excluded patients (Table 2).

To better understand the answers provided by the caregivers of patients with cognitive impairment compared to those of patients with subjective memory disorders, we separately analysed the data of the two groups.

Caregivers

A total of 54 caregivers (42 women; mean ± SD, age: 56.69 ± 13.98 years; education: 13.91 ± 4.14 years) who were present during the telemedicine session answered the telephone survey. Overall, 26 caregivers (48.15%) belonged to the same generation as the patients or were partners (46.30%) or siblings (1.85%), whereas 28 (51.85%) were part of the younger generation: sons (44.44%), nephews (3.70%), or in-home nurses (3.70%). Twenty-nine caregivers (53.70%) were employed, 21 (38.89%) were retired, and 4 (7.41%) were unemployed.

Most caregivers (87.04%) reported that they did not need technical assistance for setting up the neurological video consultation with our outpatient services, whereas 12.96% of them requested assistance. All caregivers who required technical assistance for telemedicine belonged to the same generation as the patients. Only one participant reported having conducted a neurological video consultation before the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 3).

The group of patients (27 women; mean ± SD, age: 73.19 ± 9.2 years; education: 10.80 ± 4.54 years; disease duration: 5.28 ± 2.12 years; Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score: 17.39 ± 8.19) for whom the caregivers provided survey responses had a diagnosis of AD (38.89%), amnesic MCI (27.78%), FTD (20.37%), LBD (5.56%), mixed dementia (3.70%), non-amnesic MCI (1.85%), and MSA (1.85%).

In 42.59% of the cases, caregivers reported that the patients did not have behavioural disorders, 25.93% showed slight disturbances, 25.93% showed moderate disturbances, and 5.56% had severe behavioural disorders (Table 3).

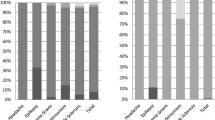

According to the responses collected on the ‘usefulness/perceived usefulness’ construct investigated by the telephone survey, caregivers reported that telemedicine was useful (87.04%, ‘very useful’; 9.26%, ‘quite useful’; and 3.70%, ‘neither useful nor useless’). All caregivers reported positive feedback regarding ‘technical quality’ (88.89%, ‘very good’ and 11.11%, ‘quite good’). Regarding ‘effectiveness’, most caregivers found telemedicine ‘very effective’ (68.52%), 11.11% found it ‘quite effective’, whereas 16.67% did not express a preference and 3.70% found it ‘very ineffective’. Most caregivers also perceived the ‘effect on interaction’ with neurologists as ‘excellent’ (88.89%) or of good quality (9.26%), whereas only one reported an interaction of poor quality (1.85%). Most caregivers ranked the ‘experience’ positively (79.63%, ‘very good’; 14.81%, ‘quite good’; and 5.56%, did not express a preference). Regarding ‘satisfaction’, caregivers were satisfied using telemedicine (90.74%, ‘very satisfied’; 7.41%, ‘quite satisfied’; and 1.85%, ‘neither satisfied nor unsatisfied’) (Table 4).

Spearman’s correlation highlighted that ‘usefulness/perceived usefulness’ was moderately correlated with ‘satisfaction’ (r = 0.635, p < 0.001). Moderate correlations were found between ‘effectiveness’ and ‘experience’ (r = 0.584, p < 0.001), and between the ‘effect on interaction’ and ‘satisfaction’ constructs (r = 0.514, p < 0.001) (Table 5).

Finally, all 54 caregivers (100%) agreed that neurological video consultation was a useful tool to reduce their burden (VAS mean ± SD: 8.56 ± 0.69).

Patients

Only eight patients diagnosed with subjective memory disorders responded independently to the survey (4 women; mean ± SD, age: 73.00 ± 8.52 years; education: 14.25 ± 2.31 years; disease duration: 3.86 ± 0.9 years; MMSE score: 28.88 ± 0.83). Five patients (62.50%) did not report perceiving behavioural disorders; instead, three patients reported the presence of slight-to-moderate behavioural disorders (slight degree in two patients (25.00%) and moderate degree in one patient (12.50%)).

None of these patients reported having used telemedicine before the COVID-19 pandemic to avail neurological consultations, and all were able to conduct the telemedicine follow-up visit without requiring technical assistance, even in instances in which another person was present during the remote consultation (37.50%). Seven patients (87.50%) lived in Northern Italy, whereas only one patient lived in Central-Southern Italy. All patients received healthcare in Northern Italy. Seven patients (87.50%) reported being retired, whereas one patient (12.50%) was employed (Table 6).

According to the responses collected on the ‘usefulness/perceived usefulness’ construct investigated by the telephone survey, this sample of patients reported that the neurological telemedicine consultation was overall useful (87.50%, ‘strongly useful’ and 12.50%, ‘quite useful’). Regarding ‘technical quality’, 87.50% reported excellent technical quality during telemedicine visits and 12.50% reported good technical quality. With regard to the ‘effectiveness’, telemedicine consultations were mostly perceived as effective by patients (87.50%, ‘very effective’ and 12.50%, ‘quite effective’). When evaluating the ‘effect on interaction’, all patients found the interaction with the neurologist to be excellent. Moreover, on the ‘experience’ construct, patients reported that overall they had a positive experience (87.50%, ‘very good experience’ and 12.50%, ‘good experience’). Finally, regarding ‘satisfaction’, all patients reported being completely satisfied of telemedicine consultation. The responses of patients did not differ statistically from those of caregivers (Table 4). No significant correlations were found between constructs examined.

Discussion

This study evaluated the experience of telemedicine in patients with cognitive deficits and their caregivers. Although there was substantial heterogeneity in the participants’ characteristics, our results demonstrated that telemedicine for routine care was effective.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, public health measures taken to contain the spread of the virus created an urgent need to integrate virtual care into the existing healthcare infrastructure. In addition, the discontinuation of face-to-face activities, including rehabilitation sessions, medical appointments, and programmes, has had a detrimental effect on cognition and exacerbated stereotypic behaviours (e.g., strict adherence to routine) in this vulnerable population and increased the pressure on caregivers [2].

Our data showed that patients and caregivers were highly satisfied with the neurological video consultation, with an overall satisfaction rate of approximately 98.15% for caregivers and 100% for patients. This supports previous findings that telemedicine is a useful tool in dementia healthcare for supporting caregivers and reducing their burden [8]. According to Europe’s Alzheimer’s Society, telemedicine has also helped patients build a good support network, kept patients well informed, ensured that medical supplies were adequate, and enabled patients to remain physically and mentally active and stay socially connected [9]. In this context, a reduction in social contact and access to health services has encouraged the use of telemedicine to reduce the risk of developing negative mental health outcomes, improve dementia symptom management, mainly AD, and provide mental health care. Moreover, it can help caregivers by providing useful guidance on non-pharmacological measures to control symptoms affected by the new confinement measures. As the disease progresses, patients become more dependent on their caregivers and experience a loss of autonomy in their activities of daily life. The relatives of patients with chronic neurological conditions are assumed to be the primary caregivers in non-medical settings. Moreover, caregivers provide physical and emotional support to patients and play key roles in their decision-making processes [10]. In the management of chronic diseases, the well-being of caregivers is crucial, as a high level of burden on them may lead to a breakdown in care. Therefore, patients and caregivers must be educated on the management of cognitive impairment [11]. Additionally, telemedicine allows health support in real-time, even from a distance, making adequate medication adjustments possible when necessary without exposing patients and caregivers to the risk of COVID-19 infection.

The responses also highlighted that caregivers found video consultation ‘very useful’ in 87.04% of cases, while they found it ‘very effective’ in only 68.52% of cases. In agreement with the guidelines of Langbecker et al. [6], in our survey, for the construct ‘usefulness/perceived usefulness’, we evaluated how an interaction by telemedicine can produce benefits; for example, perceived convenience, time and cost saving, or the effect on the continuity of care. In contrast, for the construct ‘effectiveness’ we focused on assessing whether a video consultation interaction helped improve the health status of a patient; for example, patient well-being, change in health status, quality of life, or patient empowerment (see Table 1). Therefore, this difference can be explained by the different items measured for the two constructs. However, comparison studies evaluating face-to-face visits and video consultations are needed to understand whether the lowest score to the ‘effectiveness’ construct is due to the modality in which the medical visit was delivered, or by the progressive and irreversible nature of the dementia disease. Previous studies have demonstrated that telemedicine can be more clinically effective than usual methods of care [12]; however, the available evidence is discipline-specific, which highlights the need for more studies on the clinical effectiveness of video consultation across a wider spectrum of clinical health services. These findings support the view that in the right context, telemedicine will not compromise the effectiveness of clinical care compared to conventional forms of health service delivery [12].

Overall, the data suggest that the video consultation was very useful for the participants because it reduced the burden of transportation and trips outside the home for persons with dementia and their caregivers. This is consistent with previous studies conducted in urban and rural contexts [13, 14]. We found that video consultations were beneficial in terms of financial and travel time burdens, although our sample mainly comprised people living in a metropolitan area. Another reason for the lower total travel time expenses in our sample was that almost all caregivers were family members, who were either employed or who took time off work to take their relatives to medical appointments. Previous studies [15, 16] have shown that telemedicine consultations for monitoring chronic conditions are a convenient approach because patients can avoid travelling to medical facilities for routine follow-up appointments. They are more convenient and safer for patients, and less burdensome for caregivers. The convenience of telemedicine may help mitigate these immediate difficulties and diminish care-partner stress, in part, by reducing barriers to seeking care and eliminating travel to medical appointments and other in-person therapies. In addition, the benefits of telemedicine have been reported in dementia subtypes, including frontotemporal dementia, where telemedicine has demonstrated validity as a triage tool for increasing practice outreach and efficiency [12].

Finally, although technological barriers, including lack of equipment and the inability of older adults to independently manipulate technologies, could have hindered the use of telemedicine, our results showed that most participants, including older respondents, were able to access the platform. This proves that the pandemic has accelerated the digitisation process of care. Care partners can play a key role in optimising the home environment for telemedicine by minimising clutter and background noise, and simplifying tasks for patients with cognitive impairment. Orientation and training prior to an encounter can help set clear expectations for the care partner and reduce the severity of the situation for the person with cognitive impairment.

Despite telemedicine has demonstrated many benefits during the current crisis [7] owing to the pandemic, long-term considerations to address barriers to telemedicine care deserve equal attention because of its potential to improve the accessibility of care for patients with dementia and their caregivers.

Limitations

The purpose of our study was to describe the experience of video consultations for patients with cognitive deficits and caregiver. However, the small sample size and the absence of a control group attending face-to-face consultations limited the generalisability of our data. A large multicentre study is required to further examine the application and effectiveness of this type of intervention.

Our sample population mainly inhabited urban areas; however, underserved populations (e.g. those from rural areas) may benefit more from this intervention.

Future research should aim to assess the feasibility of telemedicine for patients living in both remote and rural areas to address this limitation of the current study.

Conclusions

Our results provide baseline information for designing improved telemedicine services that can open paths to achieving the goal of a user-friendly and satisfactory experience of virtual care delivery for patients with cognitive impairment and their caregivers. Telemedicine is well received by patients and care partners, but successful delivery requires support staff and care partners to navigate technologies. The benefits of telemedicine are several and promising, and it has several possible applications in the management of frail patients. We believe that the application of technology in medicine is useful for patients, healthcare providers, and institutions, allowing easy access to medical services, avoiding stressful travel, and reducing healthcare costs and waiting lists. Future studies should address this landscape to improve the quality of service, discover the best method of use, and expand its use among frail patients.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Manca R, De Marco M, Venneri A (2020) The impact of COVID-19 infection and enforced prolonged social isolation on neuropsychiatric symptoms in older adults with and without dementia: a review. Front Psychiatry 11:585540. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.585540

Lima DP, Queiroz IB, Carneiro AHS, Pereira DAA, Castro CS, Viana-Junior AB et al (2022) Feasibility indicators of telemedicine for patients with dementia in a public hospital in Northeast Brazil during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One 17(5):e0268647. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0268647

Elbaz S, Cinalioglu K, Sekhon K, Gruber J, Rigas C, Bodenstein K et al (2021) A Systematic review of telemedicine for older adults with dementia during COVID-19: an alternative to in-person health services? Front Neurol 12:761965. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.761965

Arighi A, Fumagalli GG, Carandini T, Pietroboni AM, De Riz MA, Galimberti D et al (2021) Facing the digital divide into a dementia clinic during COVID-19 pandemic: caregiver age matters. Neurol Sci 42(4):1247–1251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-020-05009-w

Haleem A, Javaid M, Singh RP, Suman R (2021) Telemedicine for healthcare: Capabilities, features, barriers, and applications. Sens Int 2:100117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sintl.2021.100117

Langbecker D, Caffery LJ, Gillespie N, Smith AC (2017) Using survey methods in telehealth research: A practical guide. J Telemed Telecare 23(9):770–779. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X17721814

Ruggiero F, Lombi L, Molisso MT, Fiore G, Zirone E, Ferrucci R et al (2022) The impact of telemedicine on parkinson’s care during the COVID-19 pandemic: an italian online survey. Healthcare (Basel) 10(6):1065. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10061065

Daley S, Farina N, Hughes L, Armsby E, Akarsu N, Pooley J et al (2022) Covid-19 and the quality of life of people with dementia and their carers-The TFD-C19 study. PLoS One 17(1):e0262475. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0262475

Alzheimer Europe (2021) COVID-19 resources. Luxembourg. https://www.alzheimer-europe.org/Living-with-dementia/COVID-19. Accessed 19 March 2022

D’Alvano G, Buonanno D, Passaniti C, De Stefano M, Lavorgna L, Tedeschi G et al (2021) Support needs and interventions for family caregivers of patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): a narrative review with report of telemedicine experiences at the time of COVID-19 pandemic. Brain Sci 12(1):49. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12010049

Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Ward K, Beeber A, Reed D, Lathren C et al (2018) Helping dementia caregivers manage medical problems: benefits of an educational resource. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 33(3):176–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317517749466

Yi JS, Pittman CA, Price CL, Nieman CL, Oh ES (2021) Telemedicine and dementia care: a systematic review of barriers and facilitators. J Am Med Dir Assoc 22(7):1396-1402.e18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2021.03.015

Le S, Aggarwal A (2021) The application of telehealth to remote and rural Australians with chronic neurological conditions. Intern Med 51(7):1043–1048. https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.14841

Schneider RB, Biglan KM (2017) The promise of telemedicine for chronic neurological disorders: the example of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol 16(7):541–551. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30167-9

Imlach F, McKinlay E, Middleton L, Kennedy J, Pledger M, Russell L et al (2020) Telehealth consultations in general practice during a pandemic lockdown: survey and interviews on patient experiences and preferences. BMC Fam Pract 21(1):269. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-020-01336-1

Ma Y, Zhao C, Zhao Y, Lu J, Jiang H, Cao Y et al (2022) Telemedicine application in patients with chronic disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 22(1):105. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-022-01845-2

Funding

This work was supported by Ricerca Corrente’ (IRCCS RC-2023 Grant no. 01) grant from the Italian Ministry of Health. The funder had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of the data, in the writing of the report or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FR and FM developed the study design. FR, TC, GF, AP, AA and FM contributed to participant recruitment. FR and FM conducted the study and data collection. MTM conducted data analysis. FR, EZ, MTM and FM wrote the first draft of the manuscript. FR, EZ, AA, RF, ENA, BP and FM revised and edited the manuscript. VS, GC, ES and SB supervised the drafting of the manuscript and acquired the funds. All authors have read, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Foundation IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico (Protocol no. 184_2021bis).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

V. S. received compensation for consulting services and/or speaking activities from AveXis, Cytokinetics, Italfarmaco, Liquidweb S.r.l., Novartis Pharma AG and Zambon, receives or has received research supports from the Italian Ministry of Health, AriSLA, and E-Rare Joint Transnational Call. He is in the Editorial Board of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Degeneration, European Neurology, American Journal of Neurodegenerative Diseases, Frontiers in Neurology and Exploration of Neuroprotective Therapy. B. P. received compensation for consulting services and/or speaking activities from Liquidweb S.r.l B. P. is Associated Editor for Frontiers in Neuroscience. N. T. received compensation for consulting services from Amylyx Pharmaceuticals and Zambon Biotech SA. He is Associate Editor for Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience.

Informed consent

all study participants provided informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ruggiero, F., Zirone, E., Molisso, M.T. et al. Telemedicine for cognitive impairment: a telephone survey of patients’ experiences with neurological video consultation. Neurol Sci 44, 3885–3894 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-023-06903-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-023-06903-9