Abstract

Introduction

Neurological deterioration, soon after anti-copper treatment initiation, is problematic in the management of Wilson’s disease (WD) and yet reports in the literature are limited. The aim of our study was to systematically assess the data according to early neurological deteriorations in WD, its outcome and risk factors.

Methods

Using PRISMA guidelines, a systematic review of available data on early neurological deteriorations was performed by searching the PubMed database and reference lists. Random effects meta-analytic models summarized cases of neurological deterioration by disease phenotype.

Results

Across the 32 included articles, 217 cases of early neurological deterioration occurred in 1512 WD patients (frequency 14.3%), most commonly in patients with neurological WD (21.8%; 167/763), rarely in hepatic disease (1.3%; 5/377), and with no cases among asymptomatic individuals. Most neurological deterioration occurred in patients treated with d-penicillamine (70.5%; 153/217), trientine (14.2%; 31/217) or zinc salts (6.9%; 15/217); the data did not allow to determine if that reflects how often treatments were chosen as first line therapy or if the risk of deterioration differed with therapy. Symptoms completely resolved in 24.2% of patients (31/128), resolved partially in 27.3% (35/128), did not improve in 39.8% (51/128), with 11 patients lost to follow-up.

Conclusions

Given its occurrence in up to 21.8% of patients with neurological WD in this meta-analysis of small studies, there is a need for further investigations to distinguish the natural time course of WD from treatment-related early deterioration and to develop a standard definition for treatment-induced effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Wilson’s disease (WD) is an inherited disorder of copper metabolism with pathological copper accumulation, which can result in clinical symptoms in affected organs, particularly hepatic and/or neuropsychiatric manifestations [1,2,3,4]. As the disease is caused by copper overload, WD treatment is based on drugs promoting negative copper balance including (1) copper chelators (d-penicillamine [DPA], trientine [TN] or dimercaptopropane sulfonic acid [DMPS] used in China) which mainly increase urinary copper excretion; (2) drugs which inhibit copper absorption from the digestive tract (zinc salts [ZS]); or (3) drugs complexing copper into insoluble complexes, leading to increase biliary copper excretion, as well as decrease copper absorption (e.g. molybdenum salts in clinical trials) [5].

WD can be successfully treated with pharmacological agents if diagnosis is established early and anti-copper treatment is correctly introduced and monitored [5,6,7,8]. Based on international WD registries, a satisfactory outcome is reached in almost 85% of WD patients [9, 10]. Improvement of hepatic symptoms as well as liver function tests usually occurs within the first 2–6 months of anti-copper treatment initiation [1]. Improvement of neurological symptoms may take longer and in some cases, can be observed up to 3 years after treatment initiation [1]. However, since DPA was introduced in 1956, the devastating phenomenon of early (so-called ‘paradoxical’) neurological deterioration after treatment initiation has been described in some patients [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26].

Two types of clinical neurological deterioration during treatment can be distinguished: (1) early worsening that usually occurs up to 6 months of treatment initiation and is mostly connected with anti-copper therapy as a trigger and (2) late worsening, observed after 6 months of treatment introduction, which mainly results from non-compliance with anti-copper treatment and other factors [4, 5]. The majority of published cases of early neurological deterioration occurred in patients with the neurological phenotype and sometimes followed a dramatic course, for example, introduction of a full dose of DPA that led to the patient worsening to a bedridden state, which was frequently irreversible [15,16,17, 19, 24]. Over time, an association was made between introduction of the full dose of DPA and neurological deterioration [15,16,17, 19, 24] and a slow DPA titration scheme was introduced, which decreased the number of cases of early neurological deterioration [1, 5, 10]. However, the problem of early neurological deterioration has been reported after the introduction of all available anti-copper medications (DPA, TN, ZS, molybdenum salts) with different results [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44], suggesting that alternative explanations for this phenomenon need to be taken into account [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45].

Despite acknowledgement of the severe and even life-threatening consequences of early neurological deterioration, which is also a problem in the development of new WD treatments, there remains a lack of comprehensive studies on frequency and predictors. Numerous retrospective analyses of large national WD cohorts have assessed the frequency of neurological deterioration as part of secondary analyses; however, most did not use objective neurological scales [6,7,8]. Only a small number of studies and case reports have specifically analysed the phenomenon and investigated predictors [27, 28, 35, 43].

The aim of our study was to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies on early neurological deterioration, as well as discuss its definition and summarize risk factors.

Methods

This systematic review was performed in concordance with internationally accepted criteria of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement [46].

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

We searched the PubMed database (up to 15 September 2022) for original studies (prospective and retrospective), as well as case and series reports analyzing early neurological deterioration, its frequency, risk factors and outcomes in patients with WD. Search terms included: (“Wilson’s disease”/ “Wilson disease” and “early neurological worsening”), (“Wilson disease”/ “Wilson disease” and “early neurological deterioration”), (“Wilson’s disease”/ “Wilson disease” and “neurological deterioration”) and (“Wilson’s disease”/ “Wilson disease” and “neurological worsening”). Studies eligible for further analysis were (1) human studies; (2) original studies (prospective or retrospective); (3) case and series reports of pregnant WD patients; and (4) those published in English. The reference lists of extracted publications were also searched. For the purpose of this study, we defined neurological deterioration as worsening in the 6-month period after treatment introduction.

Initially, the titles and abstracts of papers retrieved by the search terms were screened independently by all authors and duplicate records were removed. Reviews, editorial, commentaries, as well as overlapped studies were excluded after assessment and revisions. Then the full text of initially eligible articles was screened. Again, incomplete reports, reviews, editorials, commentaries, conference proceedings, discussions and overlapped studies were excluded. Finally, all identified studies were analyzed and verified independently by all authors to confirm the inclusion criteria and were grouped as (1) prospective studies that aimed to analyze early neurological deterioration; (2) retrospective studies mostly presenting data from country WD registries with additional analyses of early neurological deterioration; (3) retrospective analyses focused on the early neurological deterioration phenomenon; 4) series reports and (5) case reports describing patients who deteriorated shortly after decoppering treatment initiation; and 6) diagnosis of early neurological deterioration established based on objective neurological examination (preferably using neurological scales). Only WD drug naive patients were analyzed, also the analysis according to WD phenotypic presentation if available was summarized separately. For each publication, the number of patients involved, the definition of early neurological deterioration used (if any), the phenotype of WD, the risk factors of deterioration, the treatment type and the outcome were recorded, where available.

Meta-analysis methodology

A random effects meta-analysis was used to estimate the risk of an early neurological deterioration among patients with the neurological form at diagnosis because deteriorations after treatment initiation almost never occur in other patients with WD. Heterogeneity was assessed with I2 and the chi-squared test for the Cochrane’s Q statistic. The Baujat plot was used to find studies with the greatest contribution to heterogeneity; a sensitivity analysis was carried out after the exclusion of these studies.

The study protocol was registered and received INPALSY registration number: INPALSY202290111 (https://doi.org/10.37766/inpalsy2022.9.0111).

Results

The publications search and selection process is presented in Fig. 1.

The initial PubMed search retrieved 320 records. During the search of extracted lists of references, we found an additional 5 papers [15, 25, 47,48,49]. After removal of duplicate articles, 231 publications remained. Titles, abstracts and full texts were then screened for relevance. Finally, 32 articles were included in the analysis. There were 7 prospective [32, 34, 39,40,41, 43, 44] and 9 retrospective studies [27, 28, 30, 33, 35,36,37,38, 42] presenting the early neurological deteriorations in WD patients (Table 1). There were also 16 case reports and case series presenting detailed descriptions of WD patients who had early neurological deterioration [12, 13, 15,16,17,18,19,20, 22,23,24,25,26, 47,48,49] (Table 2).

The 32 publications included 1512 WD patients in whom 217 cases of early neurological deterioration were described, indicating a frequency of 14.3%. In available analysis (excluding the papers without detailed phenotypic presentation) [42], the early neurological deterioration occurred mostly in patients with the neurological phenotype (21.8% [167/763]; see Fig. 2A shows studies in WD patients with neurological symptoms; Fig. 2B shows studies after the exclusion of studies with the greatest contribution to heterogeneity [28, 36, 44] see Supplementary Fig. 1). Deteriorations occurred very rarely in hepatic cases (1.3% [5/377]) and never in 87 asymptomatic individuals. Most deteriorations were described in patients treated with DPA: 70.5% (153/217). Less frequently, early neurological deterioration occurred in patients receiving TN (14.2% [31/217]), ZS (6.9% [15/217]), DMPS and zinc (5.0% [11/217]); molybdate (1.4% [3/217]) and 1.8% (4/217) on combined therapy with ZS and chelators.

(A) Meta-analysis available studies (apart from case reports) showing frequency of early neurological deterioration in WD patients with neurological symptoms; (B) meta-analysis of available studies showing the frequency of early neurological deterioration in WD patients with neurological symptoms after removing the studies with the greatest contribution to heterogeneity

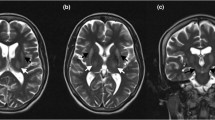

The main risk factor for neurological deterioration in WD patients was neurological phenotype (21.8% risk vs 1.3% risk in hepatic WD phenotype). Other risk factor was the initial high dose treatment with high DPA (7/16 (43.7%) reported in case reports [12, 15,16,17, 19, 24, 26]. Other well-documented risk factors of early neurological deterioration were (1) initial severity of neurological disease WD scored in clinical scales, in brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) semiquantitative scale (or lesions in pons), as initial serum concentration of neurofilaments (sNfL) [27]; (2) severity of liver disease [45] or (3) concomitant drugs blocking dopaminergic neurotransmission [35].

Data regarding patients’ recovery was provided for 128 WD patients; 24.2% (31/128) completely recovered, 27.3% (35/128) recovered partially, 39.8% (51/128) did not improve and 11 patients were lost to follow-up.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review of the literature focused on early neurological deterioration in WD patients. Based on our previous papers [27, 35], we defined early neurological deterioration as worsening up to 6 months of anti-copper treatment initiation to verify the available results and present more homogenous data. We documented that early neurological deterioration in WD occurred in about 14% of all WD patients and 21.8% of patients with neurological symptom. These data show that this phenomenon may currently occur less frequently than reported previously, particularly in some older review studies, which cited frequency up to 50% [15,16,17,18, 24]. A potential reason for this difference is that DPA was the first drug introduced as a WD treatment and initial reports of early neurological deterioration were mostly describing DPA-treated patients. The longest experience with WD treatment as well as adverse drug reactions relates to DPA and next to chelators (mostly used to treat symptomatic WD patients), which affected the assessment of the frequency of neurological deterioration. Since the link between early neurological deterioration and full-dose DPA was made, clinicians have adopted a “start low and go slow” approach to dosing, which has contributed to decreased frequency. Moreover, current WD treatment recommendations emphasize the DPA dose titration during treatment initiation [1]. However, retrospective studies and national registries still included older cases in analysis [4,5,6,7,8], which could have affected our results. But due to mostly summarized results of these studies, the separate analysis of such cases (apart from case reports [12, 15,16,17, 19, 24, 26] were not available.

It is noteworthy that the most often cited article reporting the high frequency of neurological deterioration after DPA was published in 1987 [15] and was based on a questionnaire filled in by patients or their families. Out of 54 patients, 28 completed the questionnaire and 3 patients did not have neurological presentation, so only 25 patients were analyzed (45% of initial group), of which neurological worsening occurred in 13 (52%) patients. However, in 3 cases, worsening occurred between 6 and 12 months after DPA introduction and after re-analyzing their results, they calculated a frequency of 18.5% for neurological deteriorations (10/54), not using objective neurological scales.

Our study additionally verified the irreversibility of early neurological deteriorations. Based on our systematic review, we found complete or partial recovery in around half of the patients, which is higher than previously reported [35], but the lack of improvement in other patients highlights the severe nature of the phenomenon. Indeed, these neurological complications have contributed to the search for new anti-copper drugs, such as TN or molybdate salts.

Additionally, we found that most early neurological deteriorations occurred in WD patients initially diagnosed with the neurological phenotype of the disease. Ziemssen et al. [27] found that early neurological deterioration was related to sNfL levels (as a marker of severity of neuroaxonal injury), the severity of neurological disease scored on the Unified Wilson Disease Rating Scale (UWDRS) and the chronic damage score subscale in brain semiquantitative MRI scale [27]. The semiquantitative brain MRI scale in WD consists of an acute damage score (which reflects oedema, demyelination — potentially acute — “fresh” reversible changes) and a chronic damage score (which reflects necrosis, brain atrophy as well as iron accumulation secondary to neuronal necrosis — the irreversible changes) [27]. The finding that only the chronic damage score predicts neurological worsening may suggest that in some patients who neurologically deteriorate, there are irreversible advanced neurodegenerative processes that cannot be stopped by drugs — they present with natural progression and not early neurological deterioration.

Other, proposed in the available literature, risk factors for early neurological worsening include the use of concomitant drugs blocking dopaminergic neurotransmission, lesions located in the pons and thalamus, which again indicate advanced neurological disease [35], and advanced liver disease (e.g.. evidence of chronic liver disease, splenomegaly, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia and drooling) [43].

Taken together, these observations indicate a need to distinguish the natural course of the disease from treatment-related early neurological deteriorations and additionally lead to discussions about how to establish the diagnosis and a definition of early neurological deterioration in neurologically symptomatic patients, which are currently lacking. As part of these studies, the so-called “therapeutic lag” effect [50] could be investigated, which is seen in other neurological disorders, like multiple sclerosis. After the introduction of anti-copper drugs in WD, the expected time to effects on liver function tests and liver symptoms is 4–6 months, but data on neurological symptoms are more limited and they may take longer to improve [1]. It would be interesting to conduct studies in WD to establish the expected time course of neurological symptoms regression, including initial brain MRI changes as well as biomarkers of nervous system injury [4, 27, 45].

Study limitations

Our study has some limitations. Studies were heterogenous, particularly regarding the treatment. In line with current recommendations [1] most of the symptomatic WD patients were treated with chelators (mostly DPA). Therefore, we were not able to conduct a meta-analyses comparing deterioration risk between different treatments regarding the type of anti-copper treatment and neurological deterioration. Some of the studies included only [28, 44] neurological or mostly hepatological WD patients [36]. The meta-analysis was limited by substantial heterogeneity, but the estimate was stable after excluding the studies with the greatest contribution to heterogeneity [28,36.44] (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Fig. 2B). Further, some studies included patients switched from other anti-copper drugs and/or receiving combination treatments. We tried to control for this with our inclusion criteria. Additionally, the definition of neurological worsening differed, although we tried to standardize this to a degree with our inclusion of cases within the first 6 months of treatment. Details were missing for some cases of neurological worsening in retrospective WD long-term follow-up studies and these were not included [6,7,8, 29, 51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65].

Conclusions

The early neurological deteriorations in WD occur less frequently than previously reported; however, it is still present in around 14% of WD patients and almost one quarter of patients with initial neurological phenotype of WD. Further studies are required to distinguish the natural progression of the disease from an early neurological deterioration, including considerations of “therapeutic lag” [47] as well as brain MRI studies [66], and biomarkers of central nervous system involvement [66]. Results of such studies may help develop an evidence-based definition for an early neurological deterioration.

References

European Association for the Study of the Liver (2012) EASL clinical practice guidelines: Wilson’s disease. J Hepatol 5:671–685

Ferenci P, Caca K, Loudianos G, Mieli-Vergani G, Tanner S, Sternlieb I, Schilsky ML, Cox D, Berr F (2003) Diagnosis and phenotypic classification of Wilson disease. Liver Int 23:139–142

Czlonkowska A, Litwin T, Dziezyc K, Karlinski M, Bring J, Bjartmar C (2018) Characteristic of newly diagnosed Polish cohort of patients with neurological manifestations of Wilson disease evaluated with the Unified Wilson’s Disease Rating Scale. BMC Neurol 18:34

Czlonkowska A, Litwin T, Dusek P, Ferenci P, Lutsenko S, Medici V, Rybakowski JK, Weiss KH, Schilsky ML (2018) Wilson disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers 4:21

Czlonkowska A, Litwin T (2017) Wilson disease – currently used anticopper therapy. Handb Clin Neurol 142:181–191

Bruha R, Marecek Z, Pospisilova L, Nevsimalova S, Vitek L, Martasek P, Nevoral J, Petrtyl J, Urbanek P, Jiraskova A, Ferenci P (2011) Long-term follow-up of Wilson disease: natural history, treatment, mutations analysis and phenotypic correlation. Liver Int 31:83–91

Czlonkowska A, Tarnacka B, Litwin T, Gajda J, Rodo M (2005) Wilson’s disease – cause of mortality in 164 patients during 1992–2003 observation period. J Neurol 252:698–703

Beinhardt S, Leiss W, Stattermayer AF, Graziadei I, Zoller H, Stauber R, Maieron A, Datz C, Steindl-Munda P, Hofer H, Vogel W (2014) Trauner, M.; Ferenci, P. Long-term outcomes of patients with Wilson disease in a large Austrian cohort. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 12:683–689

Schilsky ML (2014) Long-term outcome for Wilson disease: 85% good. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 12:690–691

Weiss KH, Stremmel W (2014) Clinical considerations for an effective medical therapy in Wilson’s disease. Ann N Y Sci 1315:81–85

Walshe JM, Yealland M (1993) Chelation treatment of neurological Wilson’s disease. Q J Med 86:197–204

Kleinig TJ, Harley H, Thompson PD (2008) Neurological deterioration during treatment in Wilson’s disease: question. J Clin Neurosci 15:575

Kim B, Chung SJ, Shin HW (2013) Trientine-induced neurological deterioration in a patient with Wilson’s disease. J Clin Neurosci 20:606–608

Mishra D, Kalra V, Seth R (2008) Failure of prophylactic zinc in Wilson disease. Indian Pediatr 45:151–153

Brewer GJ, Terry CA, Aisen AM, Hill GM (1987) Worsening of neurologic syndrome in patients with Wilson’s disease with initial penicillamine therapy. Arch Neurol 44:490–493

Hilz MJ, Druschky KF, Bauer J, Neundorfer B, Schuierer G (1990) Wilson’s disease – critical deterioration under high-dose parenteral penicillamine therapy. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 115:93–97

Glass JD, Reich SG, DeLong M (1990) Wilson’s disease. Development of neurological disease after beginning penicillamine therapy. Arch Neurol 47:595–596

Brewer GJ, Turkay A, Yuzbasiyan-Gurkan V (1994) Development of neurologic symptoms in a patient with asymptomatic Wilson’s disease treated with penicillamine. Arch Neurol 51:304–305

Porzio S, Iorio R, Vajro P, Pensati P, Vegnente A (1997) Penicillamine-related neurologic syndrome in a child affected by Wilson disease with hepatic presentation. Arch Neurol 54:1166–1168

Paul AC, Varkki S, Yohannan NB, Eapen CE, Chandy G, Raghupathy P (2003) Neurologic deterioration in a child with Wilson’s disease on penicillamine therapy. Indian J Gastroenterol 22:104–105

Pall HS, Williams AC, Blake DR (1989) Deterioration of Wilson’s disease following the start of penicillamine therapy. Arch Neurol 46:359–361

Veen C, Van den Hamer CJA, de Leeuw PW (1991) Zinc sulphate therapy for Wilson’s disease after acute deterioration during treatment with low-dose D-penicillamine. J Intern Med 229:549–552

Walshe JM, Munro NAR (1995) Zinc-induced deterioration in Wilson’s disease aborted by treatment with penicillamine, dimercaprol, and a novel zero copper diet. Arch Neurol 52:10–11

Brewer GJ (1999) Penicillamine should not be used as initial therapy in Wilson’s disease. Mov Disord 14:551–554

Dziezyc K, Litwin T, Czlonkowska A (2016) Neurological deterioration or symptom progression in Wilson’s disease after starting zinc sulphate treatment – a case report. Glob Drugs Therapy. https://doi.org/10.15761/GDT.1000110

Czlonkowska A, Dziezyc-Jaworska K, Klysz B, Redzia-Ogrodnik B, Litwin T (2019) Difficulties in diagnosis and treatment of Wilson disease -a series of five patients. Ann Transl Med 7(Suppl 2):S73

Ziemssen T, Smolinski L, Czlonkowska A, Akgun K, Antos A, Bembenek J, Kurkowska-Jastrzebska I, Przybyłkowski A, Skowrońska M, Rędzia-Ogrodnik B (2023) Serum neurofilament light chain and initial severity of neurological disease predict the early neuroloigcal deterioration in Wilson’s disease. Acta Neurol Belg 123:917–925

Hou H, Chen D, Liu J, Feng L, Zhang J, Liang X, Xu Y, Li X (2022) Clinical and genetic analysis in neurological Wilson’s disease patients with neurological worsening following chelator therapy. Front Genet 13:875694

Weiss KH, Askari FK, Czlonkowska A, Ferenci P, Bronstein JM, Bega D, Ala A, Nicholl D, Flint S, Olsson L, Plitz T, Bjartmar C, Schilsky ML (2017) Bis-choline tetrathiomolybdate in patients with Wilson’s disease: an open-label, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2:869–876

Zhang J, Xiao L, Yang W (2020) Combined sodium Dimercaptopropanesulfonate and zinc versus D-penicillamine as first-line therapy for neurological Wilson’s disease. BMC Neurol 20:255

Kalita J, Kumar V, Misra UK, Parashar V, Ranjan A (2020) Adjunctive antioxidant therapy in neurologic Wilson’s disease improves the outcomes. J Mol Neurosci 70:378–385

Ranjan A, Kalita J, Kumar S, Bhoi SK, Misra UK (2015) A study of MRI changes in Wilson disease and its correlation with clinical features and outcome. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 138:31–36

Samanci B, Sahin E, Bilgic B, Tufekcioglu Z, Gurvit H, Emre M, Demir K, Hanagasi HA (2021) Neurological features and outcomes of Wilson’s disease: a single-center experience. Neurol Sci 42:3829–33834

De Fabregues O, Vinas J, Palasi A, Quintana M, Cardona I, Auger C, Vargas V (2020) Ammonium tetrathiomolybdate in the decoppering phase treatment of Wilson’s disease with neurological symptoms: a case series. Brain Behav 10:e01596

Litwin T, Dzieżyc K, Karliński M, Chabik G, Czepiel W, Czlonkowska A (2015) Early neurological worsening in patients with Wilson’s disease. J Neurol Sci 355:162–167

Weiss KH, Thurik F, Gotthardt DN, Schafer M, Teufel U, Wiegand F, Merle U, Ferenci-Foerster D, Maieron A, Stauber R, Zoller H, Schmidt HH, Reuner U, Hefter H, Trocello JM, Houwen RHJ, Ferenci P, Stremmel, (2013) W. Efficacy and safety of oral chelators in tertament of patients with Wilson disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 11:1028–1035

Chang H, Xu A, Chen Z, Zhang Y, Tian F, Li T (2013) Long-term effects of a combination of D-penicillamine and zinc salts in the treatment of Wilson’s disease in children. Exp Ther Med 5:1129–1132

Linn FHH, Houwen RHJ, van Hattum J, van der Kleij S, van Erpecum KJ (2009) Long-term exclusive zinc monotherapy in symptomatic Wilson disease: experience in 17 patients. Hepatology 50:1442–1452

Marcellini M, Di Commo V, Callea F, Devito R, Comparcola D, Sartorelli MR, Carelli G, Nobili V (2005) Treatment of Wilson’s disease with zinc from the time of diagnosis in pediatric patients: a single-hospital 10-year follow-up study. J Lab Clin Med 145:139–143

Medici V, Trevisan CP, D’Inca P, Barollo M, Zancan L, Fagiuoli S, Martines D, Irato P, Sturniolo GC (2006) Diagnosis and management of Wilson’s disease: results of a single center experience. J Clin Gastroenetrol 40:936–941

Brewer GJ, Askari F, Lorincz MT, Carlson M, Schilsky M, Kluin KJ, Hedera P, Moretti P, Fink JK, Tankanow R, Dick RB, Sitterly J (2006) Treatment of Wilson disease with ammonium tetrathiomolybdate IV. Comparison of tetrathiomolybdate and trientine in a double-blind study of treatment of the neurologic presentation of Wilson disease. Arch Neurol 63:521–527

Weiss KH, Gothardt DN, Klemm D, Merle U, Ferenci-Foerster D, Schaefer M, Ferenci P, Stremmel W (2011) Zinc monotherapy is not effective as chelating agents in treatment of Wilson’s disease. Gastroenterology 140:1189–1198

Kalita J, Kumar V, Chandra S, Kumar B, Misra UK (2014) Worsening of Wilson disease following penicillamine therapy. Eur Neurol 71:126–131

Brewer GJ, Hedera P, Kluin KJ, Carlson M, Askari F, Dick RB, Sitterly J, Fink JK (2003) Treatment of Wilson disease with ammonium tetrathiomolybdate: III. Initial therapy in a total of 55 neurologically affected patients and follow-up with zinc therapy. Arch Neurol 60:379–385

Litwin T, Dzieżyc K, Czlonkowska A (2019) Wilson disease – treatment perspectives. Ann Transl Med 7:S68

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions. Explanation Elaboration Ann Intern Med 151:W65–W94

Sohtaoglu M, Ergin H, Ozekmekci S, Sonsuz A, Arici C (2007) Patient with late-onset Wilson’s disease: deterioration with penicillamine. Mov Disord 22(2):290

Berger B, Mader I, Damjanovic K, Niesen WD, Stich O (2014) Epileptic status immediately after initiation of d-penicillamine therapy in a patient with Wilson’s disease. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 127:122–124

Dusek P, Skoloudik D, Maskova J, Huelnhagen T, Bruha R, Zahorakova D, Niendorf T, Ruzicka E, Schneider SA, Wuerfel J (2018) Brain iron accumulation in Wilson’s disease: a longitudinal imaging case study during anticopper treatment using 7.0T MRI and transcranial sonography. J Magn Reason Imaging 47:282–285

Roos I, Leray E, Frascoli F, Casey R, Brown JWL, Horakova D, Havrdova EK, Trojano M, Patti F, Izquierdo G, Eichau S (2020) Delay from treatment start to full effect of immunotherapies for multiple sclerosis. Brain 143:2742–2756

Oder W, Grimm G, Kolleger H, Ferenci P, Schneider B, Deecke L (1991) Neurological and neuropsychiatric spectrum of Wilson’s disease: a prospective study of 45 cases. J Neurol 238:281–287

Chen D, Zhou X, Hou H, Feng L, Liu JX, Liang Y, Lin X, Zhang J, Wu C, Liang X, Pei Z, Li Z (2016) Clinical efficacy of combined sodium dimercaptopropanesulfonate and zinc treatment in neurological Wilson’s disease with D-penicillamine treatment failure. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 9:310–316

Zhou XX, Pu XY, Xiao X, Chen DB, Wu C, Li XH, Liang XL (2020) Observation on the changes of clinical symptoms, blood and brain copper deposition in Wilson disease patients treated with dimercaptosuccinic acid for 2 years. J Clin Neurosci 81:448–454

Couchonnal E, Lion-Francois L, Guiilaud O, Habes D, Debray D, Lamireau T, Broue P, Fabre A, Vanlemmens C, Sobesky R, Gottrand F, Bridoux-Henno L, Dumortier J, Belmath A, Poujois A, Jacquemin E, Brunet AS, Bost M, Lachaux A (2021) Pediatric Wilson’s disease: phenotypic, genetic characterization and outcome of 182 children in France. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 73:e80–e86

Li YL, Zhu XQ, Tao WW, Yang WM, Chen HZ, Wang Y (2019) Acute onset neurogical symptoms in Wilson disease after traumatic, surgical or emotional events a cross-sectional study. Medicine 98:e15917

Kumar S, Patra BR, Irtaza M, Rao PK, Giri S, Darak H, Gopan A, Kale A, Shukla A (2022) Adverse events with d-penicillamine therapy in hepatic Wilson’s disease: a single-center retrospective audit. Clinical Drug Investig 42:177–184

Tang S, Bai L, Hu Z, Chen X, Zhao J, Liang C, Zhang W, Duan Z, Zheng S (2022) Comparison of the effectiveness and safety of d-penicillamine and zinc salt treatment for symptomatic Wilson disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pharmmacol 13:847436

Brewer GJ, Dick RD, Johnson VD, Brunberg JA, Kluin KJ, Fink JF (1998) Treatment of Wilson’s disease with zinc: XV long term follow-up studies. J Lab Clin Med 132:264–278

Brewer GJ, Askari F, Dick RB, Sitterly J, Fink JK, Carlson M, Kluin KJ, Lorincz MT (2009) Treatment of Wilson’s disease with tetrathiomolybdate V. Control of free copper by tetrathiomolybdate and a comparison with trientine. Transl Res 154:70–77

Shimizu N, Fujiwara J, Ohnishi S, Sato M, Kodama H, Kohsaka T, Inui A, Fujisawa T, Tamai H, Ida S, Itoh S, Ito M, Horiike N, Harada M, Yoshino M, Aoki T (2010) Effects of long-term zinc treatment in Japanese patients with Wilson disease: efficacy, stability, and copper metabolism. Transl Res 156:350–357

Zhou X, Li XH, Huang HW, Liu B, Liang YY, Zhu RL (2011) Improved Young Scale—a scale for the neurological symptoms of Wilson disease. Chin J Nervous Ment Dis 37:171–175

Prashanth LK, Taly AB, Sinha S, Ravishankar S, Arunodaya GR, Vasudev MK, Swamy HK (2005) Prognostic factors in patients presenting with severe neurological forms of Wilson’s disease. QJM 98:557–563

Wiggelinkhuizen M, Tilanus MEC, Bollen CW, Houwen RHJ (2009) Systematic review: clinical efficacy of chelator agents and zinc in the initial treatment of Wilson disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 29:947–958

Appenzeller-Herzog C, Mathes T, Heeres MLS, Weiss KH, Houwen RHJ, Ewald H (2019) Comparative effectiveness of common therapies for Wilson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled studies. Liver Int 39:2136–2152

Dusek P, Smolinski L, Redzia-Ogrodnik B, Golebiowski M, Skowronska M, Poujois A, Laurencin C, Jastrzebska-Kurkowska I, Litwin T, Członkowska A (2020) Semiquantitative scale for assessing brain MRI abnormalities in Wilson disease: a validation study. Mov Disord 35:994–1001

Antos A, Członkowska A, Bembenek J, Skowrońska M, Kurkowska-Jastrzębska I, Litwin T (2023) Blood based biomarkers of central nervous system invovlement in Wilson’s disease. Diagnostics 13:1554

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

This manuscript has been approved for publication by all authors.

Human and animal rights

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Antos, A., Członkowska, A., Smolinski, L. et al. Early neurological deterioration in Wilson’s disease: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Neurol Sci 44, 3443–3455 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-023-06895-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-023-06895-6