Abstract

Background

This study aimed at providing diagnostic properties and normative cut-offs for the Italian ECAS Carer Interview (ECAS-CI).

Materials

N = 292 non-demented ALS patients and N = 107 healthy controls (HCs) underwent the ECAS-CI and the Frontal Behavioural Inventory (FBI). Two ECAS-CI measures were addressed: (1) the number of symptoms (NoS; range = 0–13) and (2) that of individual symptom clusters (SC; range = 0–6). Diagnostics were explored against an FBI score ≥ than the 95th percentile of the patients’ distribution.

Results

Both the NoS and SC discriminated patient from HCs. High accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity were detected for both the NoS and SC; however, at variance with SC, the NoS showed better post-test features and did not overestimate the occurrence of behavioural changes. The ECAS-CI converged with the FBI and diverged from the cognitive section of the ECAS.

Discussion

The ECAS-CI is a suitable screener for behavioural changes in ALS patients, with the NoS being its best outcome measure (cut-off: ≥ 3).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

The Edinburgh Cognitive and Behavioural ALS Screen (ECAS) [1] is the current gold-standard option to screen for cognitive and behavioural changes in ALS patients [2,3,4]. Although its cognitive section has been thoroughly explored as to its psychometrics, diagnostics and feasibility [3, 4], its behavioural one, i.e. the ECAS Carer Interview (ECAS-CI), has been to day neglected. The ECAS-CI is a short-lived, 13-item, caregiver-report questionnaire covering the major frontotemporal-spectrum behavioural features typical of ALS patients, i.e. disinhibited traits, apathetic features, reduced sympathy/empathy, obsessive–compulsive-spectrum symptoms and alterations in eating behaviour [1].

Given the prognostic relevance of behavioural changes in ALS, also with respect to caregivers’ burden [5], the availability of diagnostically sound, disease-specific behavioural instruments is clinically pivotal [3, 4]. Although a number of ALS-specific, behavioural instruments are currently available in Italy [6], a short-lived scale such as the ECAS-CI has not been addressed to this day within this Country. In addition, the ECAS-CI has never undergone a formal standardization within the international literature [3, 4].

Give the above premises, this study aimed at delivering diagnostic properties and normative cut-offs for the Italian ECAS-CI in ALS patients.

Methods

Participants

N = 292 consecutive, clinically diagnosed ALS patients [7] referred to IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano, Milano, Italy, were recruited. Patients were non-demented, as not meeting either Rascovsky et al.’s [8] or Gorno-Tempini et al.’s [9] criteria for behavioural variant-frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) and progressive non-fluent aphasia/semantic dementia, respectively. In addition, N = 107 healthy controls (HCs) were recruited via authors’ personal acquaintances. Exclusion criteria, applying to both patients and HCs, were (1) (ALS-unrelated) neurological/psychiatric diagnoses; (2) general-medical conditions possibly entailing encephalopathic features (i.e. system/organ failures or severe, uncompensated metabolic/internal diseases); and (3) uncorrected hearing/vision deficits.

Materials

Participants underwent the Italian versions of the ECAS-CI [10] and Frontal Behavioural Inventory (FBI) [11]. Both the ECAS-CI and the FBI were administered in-person to patients’ caregivers or HCs’ family members. Additionally, patients also underwent the cognitive section of the Italian ECAS [10].

Two ECAS-CI measures were addressed: (1) the number of symptoms (NoS; range = 0–13, including also those 3 assessing psychotic features) and (2) that of individual symptom clusters (SC), i.e. disinhibition, apathy, loss of sympathy/empathy, perseveration, altered eating habits and psychosis (range = 0–6). The NoS measure is scored based on the total number of specific behavioural symptoms present (out of 13), whereas the SC one based on the presence of at least one behavioural feature within each of the 6 domains addressed by the ECAS-CI.

Statistics

Diagnostics were explored via ROC analyses against an FBI score ≥ than the 95th percentile of the patients’ distribution. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values and likelihood ratios were computed at the optimal cut-off identified via Youden’s index. The minimum sample size was estimated, by means of easyROC (http://www.biosoft.hacettepe.edu.tr/easyROC/) [12], at N = 82 by addressing an allocation ratio of 1, AUC = 0.7, α = 0.05 and 1-β = 0.95. Cohen’s k was subsequently adopted to test the agreement rate between the classifications yielded by the two ECAS-CI measures.

ECAS-CI measures did not distribute normally (i.e. skewness ≥|1 and kurtosis ≥|3|) [13]; hence, construct validity against the FBI and the total score on the ECAS cognitive section was tested via Bonferroni-corrected Spearman’s correlations.

The effect of confounders (i.e. age, education, sex, C9orf72 mutation, disease duration and bulbar, respiratory, upper- and lower-limb ALSFRS-R subscores) on ECAS-CI measures was tested via negative binomial regressions, which allow to model right-skewed and overdispersed count data [14] and have been previously proved effective in analysing quantitative, behavioural outcomes of ALS patients [15]. Within such models, the threshold for significance testing was derived via Bonferroni’s correction as follows: αadjusted = 0.05/k, with k being the total number of independent variables entered into the models themselves.

The same statistical approach was employed in order to determine whether ECAS-CI measures were able to discriminate patients from HCs; within such a model, age, education and sex were covaried since the two groups were not matched for such demographics.

Analyses were run with jamovi 2.3 (https://www.jamovi.org/); the significance level (α = 0.05).

Results

Table 1 reports patients’ background and clinical features. 5.8% of patients had an FBI score ≥ than the 95th percentile of the sample (i.e. ≥ 11).

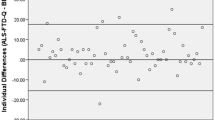

The two ECAS-CI measures showed optimal and comparable accuracy, sensitivity and specificity; however, post-test diagnostics were better for the NoS than SC (Table 2). Based on cut-offs herewith derived, 6.8% of patients presented with behavioural changes according to NoS (≥ 3), whereas 16.8% according to SC (≥ 2). A 90% agreement between the two ECAS-CI measures was found (Cohen’s k = 0.53; z = 10.3; p < 0.001), with disagreements being accounted for by 29 patients classified as presenting with behavioural changes by the NoS but not by SC.

With regard to construct validity analyses, at αadjusted = 0.025, both the NoS and SC correlated with the FBI (rs(292) ≥ 0.67; p < 0.001), whilst not with the total score on the ECAS cognitive section (p ≥ 0.215).

Negative binomial regressions for testing the effect of confounders revealed that, at αadjusted = 0.006, no demographic or clinical feature were predictive of either the NoS (p ≥ 0.02) or SC (p ≥ 0.03) within the patient cohort.

As to case–control discrimination analyses, net of age, education and sex, HCs scored lower than patients on both the NoS and SCs (Table 1).

Discussion

The present study provides, for the first time, diagnostic information and normative cut-offs for the ECAS-CI in ALS patients—delivering such information for Italian practitioners and clinical researchers.

Overall, both ECAS-CI measures herewith addressed, namely, the NoS and SC, showed adequate psychometric and diagnostic properties.

Nevertheless, albeit both the NoS and SC substantially agreed in classifying patients and showed similar accuracy and intrinsic diagnostics, the NoS yielded better post-test features and, at variance with SC, did not overestimate the occurrence of behavioural changes, being also more consistent with the prevalence yielded by the gold-standard herewith addressed (i.e. the FBI). Hence, the NoS, and not SC, should be adopted as the outcome measure of the ECAS-CI in both clinical practice and research.

Moreover, the ECAS-CI showed both convergent and divergent validity, discriminated patients from HCs and was independent of demographic and clinical confounders—this last feature supporting its adoption regardless of patients’ clinical presentation.

The ECAS-CI adds up and complements the currently available range of disease-specific/-nonspecific, behavioural tools that have been standardized in Italy within the ALS population, namely, the Emotional Lability Questionnaire (ELQ) [16], the Dimensional Apathy Scale [17], the State- and Trait-Anxiety Inventory-Form Y (STAI-Y) [18], the ALS Depression Inventory-12 (ADI-12) [19] and the Beaumont Behavioural Inventory (BBI) [15]. However, at variance with them, the ECAS-CI is less time-consuming, as well as embedded within a full, ALS-specific cognitive and behavioural screener, whose section that assesses cognition has been extensively examined for its clinimetrics and feasibility in Italy, i.e. the ECAS [10, 20, 21]. Therefore, the ECAS-CI appears to be suitable for providing, within time-restricted settings, preliminary information on patients’ behavioural status, which could be later assessed more in-depth, if useful, with the abovementioned, more specific/extensive scales [6]. After all, the ECAS-CI covers the key behavioural features of bvFTD listed within Rascovsky et al.’s [8] criteria, on which Strong et al.’s [2] classification system in turn relies for the diagnoses of ALS with behavioural impairment (ALSbi) and ALS with bvFTD. Nevertheless, it has to be borne in mind that an above-cut-off ECAS-CI alone (i.e. NoS ≥ 3) does not necessarily imply a diagnosis of ALSbi pursuant to Strong et al.’s [2] criteria, being rather an index of FTD-like behavioural changes in general: by contrast, such a nosographic categorization is up to the examiner and has to be based on which behavioural symptom(s), among those listed within the ECAS-CI; the examinee is positive to. For instance, according to Strong et al.’s [2] criteria, the detection of apathetic features alone would be sufficient for classify a patients as ALSbi.

The main limitations of this work lie in (1) the adoption of an ALS-nonspecific gold-standard (i.e. the FBI); (2) the low prevalence of FBI-detected behavioural changes, with this last aspect having possibly biased prevalence-based diagnostics (i.e. PPV and NPV); and (3) the lack of assessment of test–retest and inter-rater reliability for the ECAS-CI, which are both psychometric properties highly relevant to clinical practice and research. Additionally, two further critical elements then need to be addressed: (1) HC inclusion was herewith solely based on medical history, without specific psychometric assessment of cognition or psychopathology and (2) patients were not stratified according to Strong et al.’s [2] criteria, as this last element being beyond the scope of the present investigation. However, the agreement rate between nosographic systems [2] and the ECAS-CI, at least with regard to those diagnoses involving behavioural changes, should be addressed within future investigations.

In conclusion, the ECAS-CI is a suitable screener for behavioural changes in ALS patients, which can be informative towards the need for administering more specific/extensive, behavioural/psychological scales currently available in Italy [6]. Data herewith presented will also allow clinicians and researchers exploiting the ECAS beyond its cognitive section [10, 20,21,22], considering the crucial entailments of behavioural changes towards patients’ prognosis, clinical management and family caregiving [23].

Data availability

Datasets associated with the present study are accessible at the following link (upon request to the Corresponding Author): https://zenodo.org/record/7347119#.Y3zRDXbMJPZ.

References

Abrahams S, Newton J, Niven E, Foley J, Bak TH (2014) Screening for cognition and behaviour changes in ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 15:9–14

Strong MJ, Abrahams S, Goldstein LH, Woolley S, Mclaughlin P, Snowden J, … Turner MR (2017) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-frontotemporal spectrum disorder (ALS-FTSD): revised diagnostic criteria.Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 18:153–174

Simon N, Goldstein LH (2019) Screening for cognitive and behavioral change in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neuron disease: a systematic review of validated screening methods. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 20:1–11

Gosselt IK, Nijboer TC, Van Es MA (2020) An overview of screening instruments for cognition and behavior in patients with ALS: selecting the appropriate tool for clinical practice. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 21:324–336

Huynh W, Ahmed R, Mahoney CJ, Nguyen C, Tu S, Caga J, ... Kiernan MC (2020) The impact of cognitive and behavioral impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.Expert Rev Neurother 20:281–293

Aiello EN, D’Iorio A, Montemurro S, Maggi G, Giacobbe C, Bari V, ... Santangelo G (2022) Psychometrics, diagnostics and usability of Italian tools assessing behavioural and functional outcomes in neurological, geriatric and psychiatric disorders: a systematic review. Neurol Sci 43: 6189–6214

Brooks BR, Miller RG, Swash M, Munsat TL (2000) El Escorial revisited: revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord 1:293–299

Rascovsky K, Hodges JR, Knopman D, Mendez MF, Kramer JH, Neuhaus J, ... Miller BL (2011) Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain 134:2456–2477

Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, Kertesz A, Mendez M, Cappa SF, ... Grossman M (2011) Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants.Neurology 76:1006–1014

Poletti B, Solca F, Carelli L, Madotto F, Lafronza A, Faini A, … Silani V (2016) The validation of the Italian Edinburgh Cognitive and Behavioural ALS Screen (ECAS).Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 17:489–498

Alberici A, Geroldi C, Cotelli M, Adorni A, Calabria M, Rossi G, … Kertesz, A (2007) The Frontal Behavioural Inventory (Italian version) differentiates frontotemporal lobar degeneration variants from Alzheimer’s disease.Neurol Sci 28:80–86

Goksuluk D, Korkmaz S, Zararsiz G, Karaagaoglu AE (2016) easyROC: an interactive web-tool for ROC curve analysis using R language environment. R J 8:213

Kim HY (2013) Statistical notes for clinical researchers: assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor Dent Endod 38:52–54

Aiello EN, Depaoli EG, Gallucci M (2020) Usability of the negative binomial model for analyzing ceiling and highly-inter-individually-variable cognitive data. Neurol Sci 41:S273–S274

Iazzolino B, Pain D, Laura P, Aiello EN, Gallucci M, Radici A, … Chiò A (2022) Italian adaptation of the Beaumont behavioral inventory (BBI): psychometric properties and clinical usability. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 23:81–86

Palmieri A, Abrahams S, Sorarù G, Mattiuzzi L, D’Ascenzo C, Pegoraro E, Angelini C (2009) Emotional lability in MND: relationship to cognition and psychopathology and impact on caregivers. J Neurol Sci 278:16–20

Santangelo G, Siciliano M, Trojano L, Femiano C, Monsurrò MR, Tedeschi G, Trojsi F (2017) Apathy in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: insights from dimensional apathy scale. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 18:434–442

Siciliano M, Trojano L, Trojsi F, Monsurrò MR, Tedeschi G, Santangelo G (2019) Assessing anxiety and its correlates in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: the state-trait anxiety inventory. Muscle Nerve 60:47–55

Pain D, Aiello EN, Gallucci M, Miglioretti M, Mora G (2021) The Italian version of the ALS Depression Inventory-12. Front Neurol 12:723776

Poletti B, Solca F, Carelli L, Faini A, Madotto F, Lafronza A, ... Silani V (2018) Cognitive-behavioral longitudinal assessment in ALS: the Italian Edinburgh Cognitive and Behavioral ALS screen (ECAS).Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 19:387–395

Aiello EN, Iazzolino B, Pain D, Peotta L, Palumbo F, Radici A, … Chiò A (2022) The diagnostic value of the Italian version of the Edinburgh Cognitive and Behavioral ALS screen (ECAS). Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 23:527–531

Aiello EN, Solca F, Torre S, Carelli L, Monti A, Ferrucci R, … Poletti B (2022) Reliable change indices for the Italian Edinburgh Cognitive and Behavioural ALS Screen (ECAS). Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/21678421.2022.2134801

Lillo P, Mioshi E, Hodges JR (2012) Caregiver burden in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is more dependent on patients’ behavioral changes than physical disability: a comparative study. BMC Neurol 12:1–6

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to patients and their caregivers.

Funding

This research was funded by the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Corrente to IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano, project 23C302). Publication fees have been covered by IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Participants provided informed consent. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano (I.D.: 2013_06_25).

Conflict of interest

V.S. received compensation for consulting services and/or speaking activities from AveXis, Cytokinetics, Italfarmaco, Liquidweb S.r.l., and Novartis Pharma AG, receives or has received research supports from the Italian Ministry of Health, AriSLA and E-Rare Joint Transnational Call. He is in the Editorial Board of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Degeneration, European Neurology, American Journal of Neurodegenerative Diseases, Frontiers in Neurology. B.P. and L.C. received compensation for consulting services and/or speaking activities from Liquidweb S.r.l. N.T. received compensation for consulting services from Amylyx Pharmaceuticals and Zambon Biotech SA. He is Associate Editor for Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Poletti, B., Aiello, E.N., Solca, F. et al. Diagnostic properties of the Italian ECAS Carer Interview (ECAS-CI). Neurol Sci 44, 941–946 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-022-06505-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-022-06505-x