Abstract

Background and objective

An acute exacerbation of myasthenia gravis (MG) can lead to the life-threatening myasthenia crisis which can increase the in-hospital mortality. This study aimed to clarify the correlative factor of the severity and activity of MG and the predictors of its exacerbation.

Methods

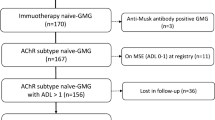

A prospective study was conducted to compare the clinical characteristics of acetylcholine receptor antibody (AChR-Ab)-positive generalized MG during acute exacerbation (AE) and in a stable state (SS). Logistic regression was used to determine risk factors, and a nomogram was developed.

Results

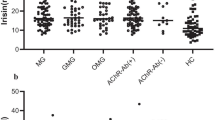

A total of 97 AChR-Ab MG patients were enrolled, of whom 44 had AE and 53 were in SS. The concentrations of AChR-Ab were 35.24 (23.26, 42.52) nmol/L and 19.51 (8.30, 36.93) nmol/L in the AE and SS groups (P = 0.005), respectively. The receiver operating characteristic curve showed that a single AChR-Ab predicted severity and acute exacerbation, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.679. Logistic regression analysis showed that, in addition to AChR-Ab (P = 0.018), bulbar symptoms (P = 0.001), interleukin (IL)-6 (P = 0.025), CD4+/CD8+ T cell ratio (P = 0.031), and CD19+ B cell proportion (P = 0.019) were independent risk factors for acute exacerbation of MG. The developed nomogram had an AUC of 0.878. The Hosmer and Lemeshow chi-square test was 4.37 (P = 0.929).

Conclusion

AChR-Ab concentration was positively correlated with the severity and activity of MG. AChR-Ab concentration, alongside bulbar symptoms, IL-6 concentration, CD4+/CD8+ T cell ratio, and CD19+ B cell proportion can predict the acute exacerbation of MG.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wendell LC, Levine JM (2011) Myasthenic crisis. Neurohospitalist 1(1):16–22

Alshekhlee A, Miles JD, Katirji B, Preston DC, Kaminski HJ (2009) Incidence and mortality rates of myasthenia gravis and myasthenic crisis in US hospitals. Neurology 72(18):1548–1554

Liu F, Wang Q, Chen X (2019) Myasthenic crisis treated in a Chinese neurological intensive care unit: clinical features, mortality, outcomes, and predictors of survival. BMC Neurol 19(1):172

Lv Z, Zhong H, Huan X, Song J, Yan C, Zhou L et al (2019) Predictive score for in-hospital mortality of myasthenic crisis: a retrospective Chinese cohort Study. Europ Neurol 81(5–6):287–293

Hsu CW, Chen NC, Huang WC, Lin HC, Tsai WC, Huang CC et al (2021) Hemogram parameters can predict in-hospital mortality of patients with Myasthenic crisis. BMC Neurol 21(1):388

Sharma S, Lal V, Prabhakar S, Agarwal R (2013) Clinical profile and outcome of myasthenic crisis in a tertiary care hospital: a prospective study. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 16(2):203–207

Sanders DB, Wolfe GI, Benatar M, Evoli A, Gilhus NE, Illa I et al (2016) International consensus guidance for management of myasthenia gravis: executive summary. Neurology 87(4):419–425

Narayanaswami P, Sanders DB, Wolfe G, Benatar M, Cea G, Evoli A et al (2021) International Consensus Guidance for Management of Myasthenia Gravis: 2020 Update. Neurology 96(3):114–122

Gilhus NE, Tzartos S, Evoli A, Palace J, Burns TM, Verschuuren J (2019) Myasthenia gravis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 5(1):30

Chen JX, Huang X, Feng HY (2021) Application of acetylcholine receptor antibody concentration in the assessment of myasthenia gravis. Chin J Nerv Ment Dis 47(5):306–310

Sanders DB, Burns TM, Cutter GR, Massey JM, Juel VC, Hobson-Webb L et al (2014) Does change in acetylcholine receptor antibody level correlate with clinical change in myasthenia gravis? Muscle Nerve 49(4):483–486

Lee I, Sanders DB (2021) Rethinking the utility of acetylcholine receptor antibody titer as a pharmacodynamic biomarker for myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve 64(4):385–387

Wang L, Wang S, Yang H, Han J, Zhao X, Han S et al (2021) No correlation between acetylcholine receptor antibody concentration and individual clinical symptoms of myasthenia gravis: a systematic retrospective study involving 67 patients. Brain Behav 11(7):e02203

Lindstrom JM, Seybold ME, Lennon VA, Whittingham S, Duane DD (1976) Antibody to acetylcholine receptor in myasthenia gravis. Prevalence, clinical correlates, and diagnostic value. Neurology 26(11):1054–9

Thanvi BR, Lo TC (2004) Update on myasthenia gravis. Postgrad Med J 80(950):690–700

Xu XH, Zhu LP, Wu JY, Zhang SZ, Yang GZ, Ba T et al (1985) Myathenia gravis: The severity of myasthenia gravis is closely related to the relative titer of AChR-Ab. Chin J Immunol 1(6):22–25

Heldal AT, Eide GE, Romi F, Owe JF, Gilhus NE (2014) Repeated acetylcholine receptor antibody-concentrations and association to clinical myasthenia gravis development. PLoS One 9(12):e114060

Ullah U, Iftikhar S, Javed MA (2021) Relationship between low and high anti-acetylcholine receptor antibody titers and clinical severity in myasthenia gravis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 31(8):965–968

Maurer M, Bougoin S, Feferman T, Frenkian M, Bismuth J, Mouly V et al (2015) IL-6 and Akt are involved in muscular pathogenesis in myasthenia gravis. Acta Neuropathol Commun 3:1

Uzawa A, Akamine H, Kojima Y, Ozawa Y, Yasuda M, Onishi Y et al (2021) High levels of serum interleukin-6 are associated with disease activity in myasthenia gravis. J Neuroimmunol 358:577634

Aricha R, Mizrachi K, Fuchs S, Souroujon MC (2011) Blocking of IL-6 suppresses experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis. J Autoimmun 36(2):135–141

Ashida S, Ochi H, Hamatani M, Fujii C, Kimura K, Okada Y et al (2021) Immune skew of circulating follicular helper T cells associates with myasthenia gravis severity. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 8(2):e945

Villegas JA, Van Wassenhove J, Le Panse R, Berrih-Aknin S, Dragin N (2018) An imbalance between regulatory T cells and T helper 17 cells in acetylcholine receptor-positive myasthenia gravis patients. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1413(1):154–162

Nizri E, Irony-Tur-Sinai M, Lory O, Orr-Urtreger A, Lavi E, Brenner T (2019) Activation of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory system by nicotine attenuates neuroinflammation via suppression of Th1 and Th17 responses. J Immunol 183(10):6681–6688

Zhang GX, Xiao BG, Bakhiet M, van der Meide P, Wigzell H, Link H et al (1996) Both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are essential to induce experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis. J Exp Med 184(2):349–356

Zhang GX, Ma CG, Xiao BG, Bakhiet M, Link H, Olsson T (1995) Depletion of CD8+ T cells suppresses the development of experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis in Lewis rats. Europ J Immuno 25(5):1191–1198

Ragheb S, Bealmear B, Lisak R (1999) Cell-surface expression of lymphocyte activation markers in myasthenia gravis. Autoimmunity 31(1):55–66

Yi JS, Guptill JT, Stathopoulos P, Nowak RJ, O’Connor KC (2018) B cells in the pathophysiology of myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve 57(2):172–184

Tandan R, Hehir MK 2nd, Waheed W, Howard DB (2017) Rituximab treatment of myasthenia gravis: A systematic review. Muscle Nerve 56(2):185–196

Jonsson DI, Pirskane R, Piehl F (2017) Beneficial effect of tocilizumab in myasthenia gravis refractory to rituximab. Neuromuscul Disord 27(6):565–568

Umay EK, Karaahmet F, Gurcay E, Balli F, Ozturk E, Karaahmet O et al (2018) Dysphagia in myasthenia gravis: the tip of the Iceberg. Acta Neurol Belg 118(2):259–266

Huang MH, King KL, Chien KY (1988) Esophageal manometric studies in patients with myasthenia gravis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 95(2):281–285

Moons KG, Altman DG, Reitsma JB, Ioannidis JP, Macaskill P, Steyerberg EW et al (2015) Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 162(1):W1-73

Funding

This work was supported by the Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Diagnosis and Treatment of Major Neurological Diseases (2020B1212060017), Guangdong Provincial Clinical Research Center for Neurological Diseases (2020B1111170002), Southern China International Joint Research Center for Early Intervention and Functional Rehabilitation of Neurological Diseases (2015B050501003 and 2020A0505020004), Guangdong Provincial Engineering Center for Major Neurological Disease Treatment, Guangdong Provincial Translational Medicine Innovation Platform for Diagnosis and Treatment of Major Neurological Disease, Guangzhou Clinical Research and Translational Center for Major Neurological Diseases (201604020010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the local ethics committee.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from patients or their family members including the consent of publication.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, J., Li, S., Feng, L. et al. Nomogram for the acute exacerbation of acetylcholine receptor antibody-positive generalized myasthenia gravis. Neurol Sci 44, 1049–1057 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-022-06493-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-022-06493-y