Abstract

Background

Among clinicians and researchers, it is common knowledge that, in ALS, cognitive and behavioral involvement within the spectrum of frontotemporal degenerations (FTDs) begun to be regarded as a fact in the late 1990s of the twentieth century. By contrast, a considerable body of evidence on cognitive/behavioral changes in ALS can be traced in the literature dating from the late nineteenth century.

Methods

Worldwide reports on cognitive/behavioral involvement in ALS dating from 1886 to 1981 were retrieved thanks to Biblioteca di Area Medica “Adolfo Ferrate,” Sistema Bibliotecario di Ateneo, University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy and qualitatively synthetized.

Results

One-hundred and seventy-four cases of ALS with co-occurring FTD-like cognitive/behavioral changes, described in Europe, America, and Asia, were detected. Neuropsychological phenotypes were consistent with the revised Strong et al.’s consensus criteria. Clinical observations were not infrequently supported by histopathological, post-mortem verifications of extra-motor, cortical/sub-cortical alterations, as well as by in vivo instrumental exams—i.e., assessments of brain morphology/physiology and psychometric testing. In this regard, as earlier as 1907, the notion of motor and cognitive/behavioral features in ALS yielding from the same underlying pathology was acknowledged. Hereditary occurrences of ALS with cognitive/behavioral dysfunctions were reported, as well as familial associations with ALS-unrelated brain disorders. Neuropsychological symptoms often occurred before motor ones. Bulbar involvement was at times acknowledged as a risk factor for cognitive/behavioral changes in ALS.

Discussion

Historical observations herewith delivered can be regarded as the antecedents of current knowledge on cognitive/behavioral impairment in the ALS-FTD spectrum.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In spite of the seminal description of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) delivered in 1869 by Jean-Martin Charcot and Alix Joffroy, who introduced the notion of “the mind [being] unaffected in ALS” [119], it took no longer than 23 years for Pierre Marie, one of the most distinguished protégés of Charcot himself, to firmly reply “yes” to his own question whether “mental functions are altered over the course of [ALS]” (p. 470) [65].

It is thereupon surprising that, among clinicians and researchers, the pathophysiological, genetic, and phenotypic link between frontotemporal degeneration (FTD) and ALS (i.e., the ALS-FTD spectrum) [18, 124] begun to be regarded as a fact only between the late 1990s and early 2000s of the twenty-first century.

Indeed, the scientific and clinical community has been provided with a nosographic system for FTD-spectrum disorders in these patients not earlier than 2009 [99, 100]. El Escorial diagnostic criteria, in fact, still under-addressed cognitive and behavioral features in ALS [16].

By contrast, within the present historical review, it is demonstrated that the recognition of extra-motor, FTD-spectrum disorders in ALS dates back at least 130 years. Herewith, European, American, and Asian reports starting from 1882 and suggestive of cognitive/behavioral changes in 174 ALS patients are presented. Such records were retrieved thanks to Biblioteca di Area Medica “Adolfo Ferrate,” Sistema Bibliotecario di Ateneo, University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy, and qualitatively synthetized. Records herewith described have been searched for up to 1981, as this being the date of publication of the first, pioneering review by Hudson [54] that actually acknowledged the association between ALS and cognitive/behavioral changes. However, Hudson’s [54] review was not exhaustive of all the records preceding 1981—which are, indeed, by far less known by the modern scientific community, and were thus intended to be brought to the light within this work.

Early clinical observations

Within the 10 years following the 1892 acknowledgment by Marie of “[mental] disturbances [being] not only highly frequent in [ALS] but also typical [of it]” (p. 470) [65], several authors worldwide begun reporting emotional lability, gelastic/dacrystic episodes, anosognosia as well as disinhibited and psychotic traits in ALS patients [80, 95, 115]. Notably, Marie [65] himself had already listed such alterations among the most characteristic features of their neuropsychological profile—in striking overlap with the current knowledge on dysexecutive behavioral phenotypes within the ALS-FTD spectrum [83].

As to cognition, early semeiotic reports described, besides a non-specific decrease in global efficiency [80, 39, 49, 95], memory deficits [105], as well as oral and written language disturbances [115, 56]—which are cognitive features currently acknowledged as typical of the ALS-FTD spectrum [83].

A turning point for the full recognition of neuropsychological involvement in ALS occurred after 1905, with Cullerre, in 1906, being the first to explicitly address it by entitling his report “Trouble mentales dans le sclerose laterale amyotrophique”—i.e., “Mental disturbances in [ALS]” [29]. Notably, the modern parallel of such a title dates back not earlier than 2003, with Lomen-Hoerth et al. [63] posing the question “Are amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients cognitively normal?.” One year after Cullerre’s [29] report, Fragnito [37] forwarded the pioneeristic notion of motor and cognitive/behavioral features in ALS not being unrelated, but rather yielding from the same underlying pathology spreading to extra-motor, frontotemporal cortices. Notably, such a hypothesis subsequently gained greater support over the second-to-sixth decades of the twentieth century: for instance, Bartoloni and D’Angelo [9] delivered, exactly 40 years after Fragnito [37], strikingly clear post-mortem evidence of frontotemporal cortex involvement in ALS (Fig. 1).

Post-mortem evidence of neuropathology within the frontotemporal cortex in a case series of ALS patients described by Bartoloni and D’Angelo [9]. Notes. ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

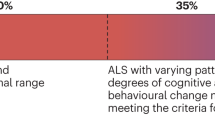

As to ante litteram stances, Fragnito [37] and Gentile [42] also noticed that neuropsychological disorders in ALS are heterogeneous in severity, somehow anticipating the current notion of a continuum of these features, ranging from sub-clinical/mild deficits (i.e., the current nosological entities of ALS-cognitive/-behavioral/-cognitive and behavioral impairment, ALSci/bi/cbi) [99] to a full-blown dementing state.

Interestingly, Cullerre [29] further described sitophobia (i.e., aversive behaviors towards food) and anosognosia in ALS patients—both features being consistent with the current knowledge of FTD-spectrum dysfunction in ALS [83].

In respect to illness awareness, it is of note that several authors reported mild-to-absent [91], moderate [92], or severe [39] loss of insight into either motor disabilities or neuropsychological changes—this being consistent with the now recognized continuum of severity of anosognosic features in ALS [83]. Relevantly, Resegotti [92] also underlined the detrimental impact of anosognosic features on adherence to and compliance with treatments—which is a renowned issue in the clinical management of ALS patients [55].

Twentieth-century clinical reports

Possibly due to the progressive acknowledgment of the aforementioned notions, starting from 1907, worldwide reports of neuropsychological impairment in ALS patients both increased in frequency and improved as to semeiotic accuracy (Table 1).

Cognitive phenotyping

As to cognition, long-term memory deficits allegedly involving episodic, prospective, or autobiographical dimensions happened to be the most frequently reported (Table 1), this somehow anticipating the recently recognized notion of primary, medial-temporal amnesic features possibly characterizing ALS patients’ cognitive profile [83]. Moreover, as to medial-temporal lobe-rooted functions, a number of twentieth-century reports also described topographical disorientation both within and outside of dementing states (Table 1).

Among instrumental domains, deficits in calculation [12, 34], praxis [21, 73], and visuo-spatial skills [31, 73] were not infrequently reported over the twentieth century. In this respect, it is notable that such domains are currently regarded as either “ALS-nonspecific” or uncommonly occurring in ALS patients [26].

Deficits of non-instrumental functions, i.e., attention and executive functioning, also started to be more precisely reported (Table 1)—this being in agreement with the notion of frontal networks subserving such processes being altered in ALS [26].

Language phenotyping

In respect to language, a number of contributions reported the occurrence of aphasic symptoms/syndromes both before and after the onset of ALS (Table 1). At times, language semiology in ALS patients was reported with a relatively high degree of details—e.g., predominant lexical-semantic deficits [116], or aphasic syndromes mostly affecting written language [40, 94].

Notably, Michaux et al. [73] described two ALS patients whose features were likely to meet current diagnostic criteria for semantic dementia (SD) [46], whereas Poppe and Tennstedt [87], within a series of patients with Pick’s disease co-occurring to either ALS or motor neuron signs, four patients presenting with either predominant lexical-semantic or morpho-syntactic involvement—i.e., resembling SD and progressive non-fluent aphasia (PNFA), respectively [46]. Both reports somehow anticipated not only the current notion of “PPA-ALS” (i.e., PPA patients with motor neuron dysfunctions) [102], but also that of both SD and PNFA possibly being co-morbid to ALS [99].

Furthermore, a number of the aforementioned reports not only described dysgraphic features [40,73, 87], which have been nowadays acknowledged as typical of ALS patients’ language profile [1], but also reading deficits—which have been thus far, by contrast, under-recognized. Taken together, such findings are strikingly consistent with the current knowledge on PPA-like language dysfunctions in ALS [85, 1, 96]—which, surprisingly, have been fully recognized as sufficient for a diagnosis of ALSci only in 2017 [99], with the first nosographic system rather focusing on dysexecutive features [100].

Behavioral phenotyping

With respect to behavioral phenotyping, obsessive–compulsive spectrum symptoms (e.g., exaggerated hoarding) and disinhibited traits (e.g., personality changes and disrupts of social conduct) started to be increasingly reported (Table 1)—these nowadays representing recognized features of ALSbi/cbi and ALS-FTD, resembling those of bvFTD [90]. Moreover, the occurrence of psychotic features of a paranoid nature happened to be more frequently reported, both before [104] and after the onset of motor symptoms [38, 118]. It is noteworthy that the association between schizophrenia spectrum disorders and ALS/FTD is nowadays acknowledged, also on a genetic basis [126].

Furthermore, semeiotic description of dementing states co-morbid to ALS begun to be finer-grained when compared, for instance, to previous reports of “euphoric dementia” [37, 65]. A number of authors indeed started hinting at either a frontal-type [125] or a progressive aphasic dementia [116, 61, 73], in a way preceding the notion of bvFTD and PPA being the dementing phenotype co-occurring to ALS [99].

Moreover, different phenotypes of behavioral, dysexecutive-like features are distinguishable in certain twentieth-century reports, describing either manic-like, disinhibited [61] vs. predominant apathetic profiles [106], as well as the co-existence of both behavioral alterations [14]. The notion of different behavioral phenotypes within the ALS-FTD spectrum is indeed nowadays recognized [83].

Late-/early-onset, seemingly reactive depression, in the context of both spared and impaired neuropsychological functioning, were also described in a number of early-twentieth-century reports [39, 91, 35]. Interestingly, depressive symptoms of mixed psychogenic and organic etiology are now estimated as moderately-to-highly prevalent in ALS [53].

The spectrum “read backwards”

Several contributions reported depressive symptoms, psychotic features, FTD-like behavioral changes as well as cognitive deficits/dementia preceding the onset of ALS (Table 1)—also by a timespan of years [109, 81, 6, 51]. Notably, such observations are consistent with the currently recognized possibility of neuropsychological symptoms appearing before motor signs in ALS-FTD spectrum disorders [75], as well as of motor neuron signs being likely to occur over the course of FTD (FTD-MND) [23]. In respect to the latter stance, the detection of pyramidal signs that however did not lead the authors to formulate a diagnosis of full-blown ALS within patients presumably presenting with FTD was not infrequently described [76, 112], this anticipating the abovementioned notion of the ALS-FTD spectrum possibly being “read backwards.” Indeed, nowadays, it is commonly recognized that patients diagnosed with bvFTD and PPA may show motor neuron signs [23].

Bulbar signs as a risk factor

Twentieth-century authors also increasingly acknowledged that cognitive/behavioral disorders happen to be more prevalent when bulbar involvement occurs [12, 109, 125]—a relatively widespread notion nowadays [120]. Notably, reports of the association between bulbar-predominant ALS and FTD-spectrum disorders are also retrievable within the late nineteenth century [115].

Histopathological records

Oppenheim and Siemerling [80] for the first time reported, in 1886, 5 patients with dementia and predominant-bulbar motor neuron signs whose autopsy revealed frontal and temporal atrophy. After a few years, also Sarbó [95] and Haenel [49] described relatively widespread, extra-motor cortical abnormalities in ALS patients showing dysexecutive, behavioral features.

However, neuropathological examinations of clinically diagnosed ALS patients showing cognitive/behavioral changes started to be more frequently reported and described with a higher degree of detail starting from the second decade of the twentieth century (Table 1). Such findings appear to be of even greater interest as often including, besides evidence on extra-motor involvement, histopathological verification of pyramidal system alterations (i.e., motor cortex and corticospinal tract) [72, 116, 61].

Pre-/orbital-/medial-frontal and temporal cortex involvement, at both macroscopic (atrophy) (Table 1) and microscopic levels (glial proliferation, astrocytosis, morphological neuronal alterations, and neuronal loss) [72, 116, 107, 110], were noted in a number of patients that nowadays would be likely to be classified as ALSci/bi/cbi, ALS-FTD, or FTD-MND, as well as fall under the relative spectrum of TDP-43 proteinopathies [18].

Moreover, sub-cortical white matter and diencephalic involvement (basal ganglia, thalamus, subthalamic nuclei) happened to be also reported (Table 1), consistently with the current notion of such structures possibly being affected by the spreading of both ALS and FTD pathology [18, 117]. Notably, Teichmann [103] and Kurachi et al. [59] also reported both macroscopic/microscopic cerebellar alterations within the post-mortem examination of ALS patients with neuropsychological involvement, this also being in line with the nowadays acknowledged possibility of the cerebellum being involved within the ALS-FTD spectrum [58].

Of interest, a number of reports allegedly succeeded in identifying the histological signature of Pick’s disease (Table 1), by also disentangling it from both Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [72, 94] pathology and senile-related physiological alterations or cerebrovascular lesions [31, 51]. By contrast, also the co-existence of Alzheimer’s and Pick’s disease pathology [87], as well as that of AD alone [125], happened to be reported—this being in line with the current knowledge of AD-like burden possibly being found at post-mortem examination of ALS cases presenting with neuropsychological changes [50].

Notes on lateralization and relative selectivity of damages can also be detected in a number of the aforementioned reports. For instance, Miskolczy and Csermely [76] envisaged a relevant anatomo-clinical correlation when describing an alleged FTD-MND patient with prominent language impairment whose post-mortem examination was suggestive of a left-greater-than-right frontotemporal cortex atrophy. Similarly, Kurachi et al. [59] described an ALS patient with prominent long-term memory impairment whose autopsy revealed a selective right-greater-than-left temporal pole atrophy—this possibly being the first description of ALS associated with the nowadays so-called right temporal variant FTD (rtvFTD) [27].

Overall, it is striking that, already in the first four decades of the twentieth century, the notion of a progressively spreading pathology beyond the motor cortex had been acknowledged as being the biological basis of neuropsychological changes in ALS [9, 48]—somehow anticipating current theories of sequential, corticofugal stages underlying both motor and cognitive/behavioral involvement within the ALS-FTD spectrum [93].

In vivo cerebral evidence

Starting from the fourth decade of the twentieth century, several authors also reported in vivo evidence of neuroanatomofunctional changes in ALS patients showing neuropsychological impairments, albeit rarely and limitedly to a restricted range of instrumental examinations (Table 1)—i.e., pneumoencephalography, EEG, CSF analysis, and, starting from 1969, CT scans [30, 34].

In this respect, the report by Miskolczy and Csermely [76] is of great relevance, as being the first to concurrently described consistent in vivo and post-mortem findings in a probable PPA case who later developed motor neuron signs—i.e., a neuropathologically confirmed Pick’s disease patient whose EEG had showed alterations within the frontal and temporal lobes.

Neuropsychological studies

As to the contribution of neuropsychology to the acknowledgment of the link between ALS and FTDs, the report by Lechélle et al. [61], Michaux et al. [73], Campanella and Bigi [21], and Boudouresques et al. [14] are of particular interest, as being the first to deliver psychometric evidence of cognitive dysfunctions—along with post-mortem and, at times, in vivo, neuroanatomofunctional correlations (Table 1).

Lechélle et al. [61] and Michaux et al. [73] described a series of ALS patient seemingly presenting with SD. A comprehensive battery of language tests indeed revealed a severe, progressive, and amodal impairment of the lexical-semantic component (with word frequency effects being also described), along with dyslexic (single-letter recognition deficits and predominantly phonological paralexias) and dysgraphic features (morpho-syntactic and phonological paragraphias). Notably, Michaux et al. [73] also described a preservation of object vs. action semantics—this possibly representing the first report of noun–verb dissociation within the ALS-FTD spectrum, a neurolinguistic phenomenon systematically documented within the last 30 years [85].

By contrast, Campanella and Bigi [21] and Boudouresques et al. [14] reported fine-grained semeiotic and psychometric descriptions of cognition and behavior in ALS patients with probable bvFTD—describing verbal inertia, apathy, anosodiaphoria, hypomanic features, and, at testing, predominant executive-attentive deficits, accompanied by possibly secondary dysfunctions of instrumental domains such as memory, praxis (including closing-in phenomena), visuo-spatial skills, and calculation.

Along with other reports alluding to psychometric testing in ALS patients [30], the abovementioned ones express an ante litteram need to objectively assess the cognitive/behavioral status of these patients. Notably, several ALS-specific psychometric screeners have been developed within the last decade, in order to provide cognitive/behavioral measures free from disease-related confounders (e.g., upper limb impairment during paper-and-pencil tasks or dysarthria within tasks requiring timed, verbal responses) [47].

Familial incidence

Starting from the nineteenth century and more frequently in the twentieth century, a number of cases have been reported of familial and possibly genetic ALS patients presenting with cognitive/behavioral dysfunctions (Table 1), both across [123, 30] and within generations [21, 36].

A number of these reports specifically suggested an autosomal dominant transmission/a high genetic penetrance [30]. Relevantly, cognitive/behavioral phenotypes were often reported as similar within such familial/genetic cases—e.g., familial cases of progressive bulbar palsy with aphasic dementia [94], slowly progressing ALS with or without dementia [21], early-onset psychosis with dementia developing within the fifth/sixth age decades [123], or slowly progressive, juvenile-onset ALS with psychosis [77].

Of note, the report by [30], who described a series of familial, probable ALS-FTD patients within an Italian kindred was revisited and extended by Giannoccaro et al. [45], who followed a number of individuals belonging to the same family and performed genetic analyses in four of them, detecting mutations consistent with the current neurogenetics of ALS-FTD spectrum disorders, among which the C9orf72 expansion. Giannoccaro et al. [45] concluded that the family described by [30] carried the C9orf72 expansion.

Finally, it is noteworthy that, within twentieth-century case series of ALS with FTD-like involvement, a familiarity with other neuropsychiatric disorders (e.g., psychosis, mood disorders, and epilepsy) was noted (Table 1) this possibly representing an ante litteram recognition of the genetic association between the ALS-FTD spectrum and unrelated brain disorders, which is nowadays believed to be underpinned by the phenotypic heterogeneity yielded from C9orf72 mutations [25]. Such evidence appear to be even more consistent when referring to psychotic disorders (Table 1), as well as in line with the current knowledge on schizophrenia spectrum disorders frequently occurring within the genealogical tree of ALS and FTD patients, possible due to C9orf72-related genotypes [70].

Extra-pyramidal involvement

As early as 1963 [4], also the nowadays certified occurrence of extra-pyramidal systems possibly being involved in ALS with FTD-spectrum disorders [88] had been reported in Europe. It is of note that such cases were addressed as resembling the ALS-parkinsonism-dementia complex (ALS-PDC), identified as endemic in Guam and in the Kii peninsula starting from the 1950s (Supplementary Material 1).

For instance, Boudouresques et al. [14], who reported a French ALS patients with co-morbid frontal-like dementia who also showed parkinsonisms within the early stages of the disease. Similarly, La Maida et al. [60] described a patient whose onset symptoms included both pyramidal and extra-pyramidal involvement, as well as depressive and apathetic features.

Conclusions

Within this historical review, strong evidence for the acknowledgment of extra-motor, frontotemporal-like cognitive/behavioral alterations in ALS dating back over 130 years ago is provided. Despite being flawed by the inherent lack of scientific progress nowadays achieved, these early reports outstandingly align with the current notion of ALS and FTDs being linked, not only at a phenotypic level but also from anatomofunctional, histopathological, and genetic points of view. It is indeed not incautious to state that several landmarks on the link between ALS and FTD had been reached way before the late 1990s of the twentieth century (Fig. 2). It has then to be noted that, between 1981 and the early 2000s, a number of reports can be traced that somehow paved the path to the full acknowledgment of the ALS-FTD spectrum occurred with the first, dedicated nosographic system by Strong et al. [100]—as indexed by a number reviews that elegantly summarized evidence at that time available, among the most remarkable being those by Strong et al. [101] and Neary et al. [79], with some other, relevant reports between 1981 and the early 2000s being also more recently brought to the light by Alberti et al. [2]. The present work also follows up to and completes the previous one by Bak and Hodges [7], who pioneeristically addressed certain of the historical records herewith described, and is complemented by an extremely recent, historical work by Carlos and Josephs [22] who focused on the centenary journey leading to the acknowledgment of the neuropathological basis of FTD-spectrum disorders.

Timeline of historical milestones for the recognition of the association between ALS and FTD. Notes. ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; FTD, frontotemporal degeneration; NPs, neuropsychological; ALS-PDC, ALS-parkinsonism-dementia-complex; MND, motor neuron disease; FTSD, frontotemporal spectrum disorders; PPA, primary progressive aphasia

Nineteenth- and twentieth-century authors also appear to urge modern neuroscientists to exert caution in addressing neurodegenerative conditions as discrete nosological entities, as well as to pay greater attention to semiology, since neuropsychology—a predominantly clinical discipline—should arguable be credited the most for sparking the fire that led to recognize that “the mind is affected in ALS.”

Abbreviations

- ALS:

-

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- ALSbi:

-

ALS with behavioral impairment

- ALSci:

-

ALS with cognitive impairment

- ALScbi:

-

ALS with cognitive and behavioral impairment

- ALS-PDC:

-

ALS-parkinsonism-dementia complex

- ALS-FTD:

-

ALS with frontotemporal dementia

- FTD:

-

Frontotemporal degeneration

- bvFTD:

-

Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia

- PNFA:

-

Progressive non-fluent aphasia

- PPA:

-

Primary progressive aphasia

- SD:

-

Semantic dementia

References

Aiello EN, Feroldi S, Preti AN, Zago S, Appollonio IM (2021) Dysgraphic features in motor neuron disease: a review. Aphasiology 1–26

Alberti P, Fermi S, Tremolizzo L, Riva MA, Ferrarese C, Appollonio I (2010) Demenza e sclerosi laterale amiotrofica: da associazione insolita a continuum. Psicogeriatria 1:24–32

Allen IV, Dermott E, Connolly JH, Hurwitz LJ (1971) A study of a patient with the amyotrophic form of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Brain 94:715–724

Alliez J, Roger J (1963) Sclérose latérale amyotrophique avec démence et syndrome parkinsonien. Ann Med Psychol 1:489

Androp S (1940) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with psychosis. Psychiatric Q 14:818–825

Astwazaturow A (1911) Ein Fall von post-traumatischer spinaler Amyotrophien nebst eine Bemerkungen ùber sogen. Poliomyelitis Anterior Chronic Dtsch Z Nervenheilkd 42:353–360

Bak TH, Hodges JR (2001) Motor neurone disease, dementia and aphasia: coincidence, co-occurrence or continuum? J Neurol 248:260–270

Barrett AM (1913) A case of Alzheimer’s disease with unusual neurological disturbances. J Nerv Ment Dis 40:361–374

Bartoloni M, D’Angelo C (1947) Reperti istopatologici nella sclerosi laterale amiotrofica al di fuori della via piramidale. Il Lavoro Neuropsichiatrico 2:193–220

Bartoloni M (1950) Malattia di Pick e sclerosi laterale amiotrofica. Il Lavoro Neuropsichiatrico 7:64–80

Beau JMP (1964) Troubles mentaux et Sclérose Laterale Amyotrophique. Thèse de Médecine, Paris

Bonaretti T (1959) Su due casi di sclerosi laterale amiotrofica ad inizio pseudobulbare preceduta da decadimento psichico. Giornale di Psichiatria e Neuropatologia 87:705–723

Bonduelle M (1975) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. In Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW (eds. Vinken PJ and Bruyn GW) Handbook of clinical neurology, System disorders and atrophies, part 2. Oxford 22:313-323

Boudouresques J, Toga M, Roger J (1967) Etat demential, sclerose lateral amyotrophique, syndrome extrapyramidal: etude anatomique. Disc Nosologique Rev Neurol 16:693–704

Brion S (1980) L’association maladie de Pick et sclérose latérale amyotrophique. Encephale 6:259–286

Brooks BR, Miller RG, Swash M, Munsat TL (2000) El Escorial revisited: revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Motor Neuron Dis 1:293–299

Burnstein MH (1981) Familiar amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, dementia, and psychosis. Psychosomatics 22:151–157

Burrell JR, Halliday GM, Kril JJ, Ittner LM, Götz J et al (2016) The frontotemporal dementia-motor neuron disease continuum. Lancet 388:919–931

Büscher J (1922) Zur Symptomatologie der sog. Amyotrophische Lateralsklerose (Ein Beitrag zur Klinik un Histologie). Archiv Psychiatr Nervenkr 66:61–145

Caidas M (1966) Sclérose Latérale Amyotropique associée à la démence et au parkinsonisme. Acta Neurol Bel 66:719–731

Campanella G, Bigi A (1959) Su un caso di sclerosi laterale amiotrofica a carattere familiare. Giornale di Psichiatria e Neuropatologia 87:804–811

Carlos AF, Josephs KA (2022) Frontotemporal lobar degeneration with TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43): its journey of more than 100 years. J Neurol 23:1–25

Cerami C, Marcone A, Crespi C, Iannaccone S, Marangoni C et al (2015) Motor neuron dysfunctions in the frontotemporal lobar degeneration spectrum: a clinical and neurophysiological study. J Neurol Sci 351:72–77

Chateau R, Fau R, Tommasi M, Groslarnbert R, Perret J et al (1966) Amyotrophie distale lente des quatre membres avec évolution démentielle (forme amyotrophique du syndome de Creutzfeld-Jakob?) (Etude anatomo-clinique). Rev Neurol 115:955–964

Chi S, Jiang T, Tan L, Yu JT (2016) Distinct neurological disorders with C9orf72 mutations: genetics, pathogenesis, and therapy. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 66:127–142

Christidi F, Karavasilis E, Rentzos M, Kelekis N, Evdokimidis I et al (2018) Clinical and radiological markers of extra-motor deficits in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Front Neurol 9:1005

Coon EA, Whitwell JL, Parisi JE, Dickson DW, Josephs KA (2012) Right temporal variant frontotemporal dementia with motor neuron disease. J Clin Neurosci 19:85–91

Corsino GM, Lugaresi E (1956) Sclerosi laterale amiotrofica e turbe psichiche. Rivista Sperimentale di Freniatria 80:870–876

Cullerre A (1906) Troubles mentales dans la sclérose latérale amyotrophique. Archives de Neurologie 21:433–450

Dazzi P, Finizio FS (1969) Sulla sclerosi laterale amiotrofica familiare. Contributo clinico. G Psichiatr Neuropatol 97:299–337

De Caro D (1941) Un caso di sclerosi laterale amiotrofica con demenza. Contributo allo studio delle lesioni corticali nella malattia di Charcot. Rass Studi Psichiatrici 30:705–22

de Morsier G (1967) Un cas de maladie de Pick avec sclérose latérale amyotrophique terminale. Contribution à la semiologie temporale. Rev Neurol 116:373–82

Delay J, Brion S, Escourolle R, Marty R (1959) Sclérose latérale amyotrophique et démence (a propos de deux cas anatomo-cliniques). Rev Neurol 100:191–204

Ferguson JH, Boller F (1977) A different form of agraphia: syntactic writing errors in patients with motor speech and movement disorders. Brain Lang 4:382–389

Fernàndez SE (1908) Un caso de sclerosis lateral amiotròfica con sintoma psiquicos. El Sìglo Medico 55:370–373

Finlayson MH, Guberman A, Martin JB (1973) Cerebral lesions in familiar amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and dementia. Acta Neuropathol 26:237–246

Fragnito O (1907) I disturbi psichici nella sclerosi laterale amiotrofica. Annali di Neurologia 25:273–287

Fragola V (1918) Un caso di sclerosi laterale amiotrofica associato a disturbi mentali. Annali del Manicomio Provinciale di Catanzaro 5:80–97

Franceschi F (1902) Un caso di sclerosi laterale amiotrofica ad inizio bulbare. Riv Patol Nerv Ment 7:433–454

Friedlander JW, Kesert BH (1948) The role of psychosis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Nerv and Ment Dis 107:243–250

Friedrich G (1940) Pathologisch-anatomischer Nachweis des vorkommens der bickeschen krankheit in 2 Generationen. Z gesamte Neurol Psychiatr 170:311–330

Gentile E (1909) I disturbi psichici nella sclerosi laterale amiotrofica. Annali della Clinica delle Malattie Mentali e Nervose della R. Università di Palermo 3:330–49

Gentili C, Volterra V (1960) La dissoluzione verbo-mimico-emotiva nella sclerosi laterale amiotrofica. G Psichiatr Neuropatol 88:467–496

Gerber Y, Naville F (1921) Contribution à l’etude histologique de la Sclérose latérale amyotrophique. Encéphale 16:113–126

Giannoccaro MP, Bartoletti-Stella A, Piras S, Casalena A, Oppi F et al (2018) The first historically reported Italian family with FTD/ALS teaches a lesson on C9orf72 RE: clinical heterogeneity and oligogenic inheritance. J Alzheimer’s Dis 62:687–697

Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, Kertesz A, Mendez M et al (2011) Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology 76:1006–1014

Gosselt IK, Nijboer TC, Van Es MA (2020) An overview of screening instruments for cognition and behavior in patients with ALS: selecting the appropriate tool for clinical practice. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 21:324–336

Gozzano M (1936) Istopatologia della sclerosi laterale amiotrofica. Riv Neurol 5:165–216

Haenel H (1903) Zen pathogenese der Amyotrophischen Lateralsklerose. Archiv Psychiatrie Nervenkr 37:45–61

Hamilton RL, Bowser R (2004) Alzheimer disease pathology in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol 107:515–522

Hanau R (1960) Su un caso di sclerosi laterale amiotrofica con turbe psichiche. Studi Sassaresi 38:119–130

Hart MN, Cancilla PA, Frommes S, Hirano A (1977) Anterior horn cell degeneration and Bunina-type inclusions associated with dementia. Acta Neuropathol 38:225–228

Heidari ME, Nadali J, Parouhan A, Azarafraz M, Irvani SSN et al (2021) Prevalence of depressive disorder among amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 287:182–190

Hudson AJ (1981) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and its association with dementia, parkinsonism and other neurological disorders: a review. Brain 104:217–247

Huynh W, Ahmed R, Mahoney CJ, Nguyen C, Tu S et al (2020) The impact of cognitive and behavioral impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Expert Rev Neurother 20:281–93

Ichikawa H, Miller MW, Kawamura M (2011) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and language dysfunction: kana, kanji and a prescient report in Japanese by Watanabe (1893). Eur Neurol 65:144–9

Kaiya H (1974) Zur Klinik und pathologischen Anatomie des Muskelatrophie-Parkinsonismus-Demenz-Syndroms. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkrankd 219:13–27

Kaliszewska A, Allison J, Col TT, Shaw C, Arias N (2021) Elucidating the role of cerebellar synaptic dysfunction in C9orf72-ALS/FTD—a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Cerebellum 21(4):681–714

Kurachi M, Koizumi T, Matsubara R, Isaki K, Oiwake H (1979) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with temporal lobe atrophy. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 33:205–215

La Maida CG, Meregalli C, Gorini R (1974) Considerazioni su un caso di sindrome extrapiramidale (forma acinetico-ipertonica) associata ad un quadro di s.l.a. e disturbi psichici. Il Lavoro Neuropsichiatrico 54:187–211

Léchelle P, Buge A, Leroy R (1954) Maladie de Pick. Sclerose latérale amyotrophique terminale. Bull Mém Soc Med Hop Paris 70:1090–94

Levi PG (1958) Studio clinico, anatomo-patologico ed istopatologico di un caso con sintomatologia di sclerosi laterale amiotrofica, associata a turbe psichiche. Neuropsichiatria 14:63–80

Lomen-Hoerth C, Murphy J, Langmore S, Kramer JH, Olney RK, Miller B (2003) Are amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients cognitively normal? Neurology 60:1094–1097

Marchand MM, Dupouy (1914) Sclérose lateral amyotropique post-traumatiques and troubles mentaux. Archives de Neurologie 320–321

Marie P (1892) Leçons sur le maladies de la moelle. Masson & Cie 470–471

Marie P (1887) Observation de sclerose latérale amyotrophique sans lèsion du faisceau pyramidal au niveau des pédoncules. Archives de Neurologie 13:387–392

Martini A (1916) I disturbi mentali nella sclerosi laterale amiotrofica. Rivista Critica di Clinica Medica. 17:197–203 209–212 221–225 233–235

Mass O (1904) Ueber ein selten beschriebenes familiàres nervenleiden. Berl Klin Wochenschrift 2832–834

Matzdorff P (1925) Zur Pathogenese der Amyotrophischen Lateralslerose. Z gesamte Neurol Psychiatr 94:106–118

McLaughlin RL, Schijven D, Van Rheenen W, Van Eijk KR, O’Brien M et al (2017) Genetic correlation between amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and schizophrenia. Nat Commun 8:1–12

Meller C (1940) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with psychosis (paranoid type). Minn Med 23:858–859

Meyer A (1929) Ueber eine der amyotrophischen Lateralsklerose nahestende Erkrankung mit psychischen Stoerungen. Z gesamte Neurol Psychiatr 121:107–128

Michaux L, Samson M, Harl JM, Gruener J (1955) Evolution démentielle de duex cas de sclérose latérale amyotrophique accompagnée d’aphasie. Rev Neurol 92:357–367

Minauf M, Jellinger K (1969) Kombination von amyotrophischer lateralsklerose mit Pickscher krankheit. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkrankd 212:279–288

Mioshi E, Caga J, Lillo P, Hsieh S, Ramsey E et al (2014) Neuropsychiatric changes precede classic motor symptoms in ALS and do not affect survival. Neurology 82:149–155

Miskolczy D, Csermely H (1939) Ein atypischer Fall von Pickscher Demenz. Allg Zeitschr ges neur Psych 110:304–315

Munch-Petersen CJ (1931) Studien ϋber erbliche Erkrankungen des Zentralnervensystems II. Die familiar, amyotrophische Lateralsklerose. Acta Neurol Psychiatr Belgica 6:65–78

Myrianthopoulos NC, Smith J (1960) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with progressive dementia and with pathologic findings of the Creutzfeldt-Jakob syndrome. Neurology 2:603–610

Neary D, Snowden JS, Mann DM (2000) Cognitive change in motor neurone disease/amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (MND/ALS). J Neurol Sci 180:15–20

Oppenheim H, Siemerling E (1886) Mitteihmgen über pseudobulbar Paralyse und acute bulbar Paralyse. Berliner Klinische Wchenschrift 23:791–794

Ottonello P (1929) Sulla sclerosi laterale amiotrofica. (Contributo clinico ed anatomopatologico). Rassegna di Studi Psichiatrici 18:221–54 397–509 557–639

Parnitzke KH, Seidel R (1961) Genetische Beziehungen zwiscen Myatrophien und Psychosen. Dtsch Z Nervenheilkd 183:180–186

Pender N, Beeldman E, De Visser M, De Haan RJ et al (2020) Cognitive and behavioural impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Curr Opin Neurol 33:649–654

Pinsky L, Finlayson MH, Libman I, Scott BH (1975) Familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with dementia: a second Canadian family. Clin Genet 7:186–191

Pinto-Grau M, Hardiman O, Pender N (2018) The study of language in the amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-frontotemporal spectrum disorder: a systematic review of findings and new perspectives. Neuropsychol Rev 28:251–268

Pisseri P (1963) Sclerosi laterale amiotrofica e malattie mentali. Rassegna critico-bibliografica corredata da un’osservazione personale. Neuropsichiatria 19:303–09

Poppe W, Tennstedt A (1963) Klinisch- und pathologisch-anatomische Untersuchungen aber Kombinationsformen praeseniler Hirnatrophien (Pick, Alzheimer) mit spinalen atrophisierenden Prozessen. Psychiatrie et Neurologie 145:322–344

Pupillo E, Bianchi E, Messina P, Chiveri L, Lunetta C et al (2015) Extrapyramidal and cognitive signs in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a population based cross-sectional study. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 16:324–330

Raithel W (1941) Kombination einer Schizophrenie mit amyotrophischer Lateralsklerose. Allgemeine Zeitschrift fiir Psychiatrie 118:48–59

Rascovsky K, Hodges JR, Knopman D, Mendez MF, Kramer JH et al (2011) Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain 134:2456–2477

Raymond F, Cestan R (1905) Dix-huit cas de sclerose laterale amyotrophique avec autopsie. Rev Neurol 13:504–508

Resegotti E (1907) Un caso di sclerosi laterale amiotrofica osservato nella clinica neuropatologica di Pavia. Il Morgagni 49:301–316

Riku Y, Seilhean D, Duyckaerts C, Boluda S, Iguchi Y, Ishigaki S, Iwasaki Y, Yoshida M, Sobue G, Katsuno M (2021) Pathway from TDP-43-related pathology to neuronal dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Int J Mol Sci 22:3843

Robertson E (1953) Progressive bulbar paralysis showing heredofamiliar incidence and intellectual impairment. Arch Neurol Psychiatr 69:197–207

Sarbó A (1898) Beitrag Symptomatologie und pathologischen histologie der amyotropischen lateralsklerose. Dtsch Z Nervenheilkd 31:337–345

Sbrollini B, Preti AN, Zago S, Papagno C, Appollonio IM, Aiello EN (2021) Language impairment in motor neuron disease phenotypes different from classical amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a review. Aphasiology 1–24

Sherratt RM (1974) Motor neurone disease and dementia: probably Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Proc R Soc of Med 67:1063

Smith MC (1960) Nerve fibre degeneration in the brain in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 23:269–82

Strong MJ, Abrahams S, Goldstein LH, Woolley S, Mclaughlin P et al (2017) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-frontotemporal spectrum disorder (ALS-FTSD): revised diagnostic criteria. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 18:153–174

Strong MJ, Grace GM, Freedman M, Lomen-Hoerth C, Woolley S et al (2009) Consensus criteria for the diagnosis of frontotemporal cognitive and behavioural syndromes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Motor Neuron Dis 10:131–146

Strong MJ, Grace GM, Orange JB, Leeper HA (1996) Cognition, language, and speech in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a review. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 18:291–303

Tan RH, Guennewig B, Dobson-Stone C, Kwok JB, Kril JJ et al (2019) The underacknowledged PPA-ALS: a unique clinicopathologic subtype with strong heritability. Neurology 92:1354–1366

Teichmann E (1935) Uber einen der amyotrophischen lateralsklerose nahestehenden. Krankheitsprozefi mit psychischen Symptomen. Z Gesamte Neurol Psychiatr 154:32–44

Tirico JG (1940) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis occuring in dementia praecox. Med Bull Vet Admin 17:180–181

Tranquilli E (1890) Sopra un caso di atrofia muscolare progressiva (sclerosi laterale amiotrofica). Osservazione clinica e note critiche. Archivio di Psichiatria Scienze Penali ed Antropologia Criminale 11:503–27

Tretiakoff C, Amorim MF (1924) Un caso de esclerose lateral amyotrophica pseudo-polynevritica em uma alienada portadora de tuberculose intestinal. Memórias do Hospício de Juquery (São Paulo, Brazil) 1:81–90

Tronconi V (1941) Sindrome demenziale presenile e sclerosi laterale amiotrofica. Rivista Sperimentale di Freniatria 65:811–813

Tscherning R (1921) Muskeldystrophie und Dementia praecox; ein Beitrag zur Erblichkeitsforschung. Z gesamte Neurol Psychiatr 69:169–181

Van Bogaert L (1925) Les troubles mentaux dans la sclérose latérale amyotrophique. Encéphale 20:27–47

Van Reeth P, Perier O, Coers C, Van Bogaert L (1961) Démence de Pick associée à une sclérose latérale amyotrophique atypique. Acta Neurologica et Psichiatrica Belgica 61:309–325

Vella G, Mariani G (1960) Inizio nevrotico ed evoluzione psicotica in una sclerosi laterale amiotrofica. Rivista di Neurologia 30:738–42

Von Bagh K (1941) Ùber anatomiche Befunde bei 30 Fàllen von systematischer Atrophie der Grofihirinde (Pickscher Krankheit) mit besonderer Berùcksichtigung der Stammganglien und der langen absteigenden Leitungsbahnen. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkrankd 114:68–70

Von Braunmùhl V (1932) Pickischer krankheit und amyotrophische lateralsklerose. Allgemeine Zeitschrift fiir die Gesamnte Neurologie und Psychiatrie 96:364–366

Von Matt K (1964) Progressive bulbärparalyse und dementielles syndrom. Psychiatrie und Neurologie 148:354–364

Watanabe E (1893) Hishitsu Undousei Shitsugo-sho to Enzuikyumahi no Shinkousei Kin-ishuku o Gappei-seru Kanja ni tuite (A patient who manifested cortical motor aphasia concurrently with bulbar and progressive muscular atrophy). J Okayama Med Assoc 40:138–144

Wechsler IS, Davidson C (1932) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with mental symptoms. Arch Neurol Psichiatr 27:859–881

Westeneng HJ, Verstraete E, Walhout R, Schmidt R, Hendrikse J, Veldink JH, van den Heuvel MP, van den Berg LH (2015) Subcortical structures in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol Aging 36:1075–1082

Westphal A (1925) Schizophrenie Krankheitsprozesse und amyotrophische lateralsklerose. Archiv Psychiatr Nervenkr 74:310–325

Wicks P, Albert SM (2018) It’s time to stop saying “the mind is unaffected” in ALS. Neurology 91:679–681

Yang T, Hou Y, Li C, Cao B, Cheng Y, Wei Q, Zhang L, Shang H (2021) Risk factors for cognitive impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 92:688–693

Yase Y, Matsumoto N, Azuma K, Nakai Y, Shiraki H (1972) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis association with schizophrenic symptoms and showing Alzheimer’s tangles. Arch Neurol 27:118–128

Yuasa R (1970) Amyothrophic lateral sclerosis with dementia. Clinical Neurology (Tokyo) 10:569–577

Yvonneau M, Vital C, Belly C, Coquet M (1971) Syndrome familial de sclérose latérale amyotrophique avec démence. Encéphale 60:449–462

Zago S, Poletti B, Morelli C, Doretti A, Silani V (2011) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia (ALS-FTD). Arch Ital Biol 149:39–56

Ziegler LL (1930) Psychotic and emotional phenomena associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol Psychiatr 24:930–937

Zucchi E, Ticozzi N, Mandrioli J (2019) Psychiatric symptoms in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: beyond a motor neuron disorder. Front Neurosci 13:175

Acknowledgements

The authors are extremely grateful to the Biblioteca di Area Medica “Adolfo Ferrate,” Sistema Bibliotecario di Ateneo, University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy, for providing us with the historical works herewith reported.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Milano within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. Research partially supported by the Italian Ministry of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

None.

Conflict of interest

V. S. received compensation for consulting services and/or speaking activities from AveXis, Cytokinetics, Italfarmaco, Liquidweb S.r.l., Novartis Pharma AG, and Zambon. Receives or has received research supports form the Italian Ministry of Health, AriSLA, and E-Rare Joint Transnational Call. He is in the Editorial Board of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Degeneration, European Neurology, American Journal of Neurodegenerative Diseases, and Frontiers in Neurology. B. P. received compensation for consulting services and/or speaking activities from Liquidweb S.r.l.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zago, S., Lorusso, L., Aiello, E.N. et al. Cognitive and behavioral involvement in ALS has been known for more than a century. Neurol Sci 43, 6741–6760 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-022-06340-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-022-06340-0