Abstract

Introduction

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) encompasses a wide spectrum of genetic, clinical, and histological findings. Sex is emerging as a potential biological variable influencing FTD heterogeneity; however, only a few studies explored this issue with nonconclusive results.

Objective

To estimate the role of sex in a single-center large cohort of FTD patients.

Methods

Five hundred thirty-one FTD patients were consecutively enrolled. Demographic, clinical, and neuropsychological features, survival rate, and serum neurofilament light (NfL) concentration were determined and compared between sex.

Results

The behavioral variant of FTD was more common in men, whereas primary progressive aphasia was overrepresented in women (p < 0.001). While global cognitive impairment was comparable, females had a more severe cognitive impairment, namely in Trail Making Test parts A and B (p = 0.003), semantic fluency (p = 0.03), Short Story Recall Test (p = 0.003), and the copy of Rey Complex Figure (p = 0.005). On the other hand, men exhibited more personality/behavioral symptoms (Frontal Behavior Inventory [FBI] AB, p = 0.003), displaying higher scores in positive FBI subscales (FBI B, p < 0.001). In particular, apathy (p = 0.02), irritability (p = 0.006), poor judgment (p = 0.033), aggressivity (p = 0.008), and hypersexuality (p = 0.006) were more common in men, after correction for disease severity. NfL concentration and survival were not statistically different between men and women (p = 0.167 and p = 0.645, respectively).

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that sex is a potential factor in determining FTD phenotype, while it does not influence survival. Although the pathophysiological contribution of sex in neurodegeneration is not well characterized yet, our findings highlight its role as deserving biological variable in FTD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sex influences on brain functioning have been gaining increasing attention in both basic and clinical sciences [1]. Differences between men and women have been demonstrated in physiological as well as in pathological conditions in the brain [2, 3], and the role of sex is emerging as a crucial biological variable in the field of neurodegenerative diseases [4, 5].

In the context of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has been largely explored for sex dissimilarities, mainly prompted by the higher AD prevalence in women [6, 7]. A large body of research has unraveled different risk factors and hormone influence in AD, along with distinct clinical presentations and specific brain changes between males and females [6, 8,9,10].

Conversely, few studies are available about the role of sex in frontotemporal dementia (FTD), probably due to the similar disease prevalence in men and women in clinical cohort studies and the lack of epidemiological studies on a possible role of sex in this disease [11].

FTD is characterized by a wide heterogeneity in terms of clinical, genetic, and neuropathological features. Exploring the factors that might contribute to this heterogeneity may represent a great challenge. Different phenotypes have been described on the basis of presenting clinical symptoms: the behavioral variant of FTD (bvFTD), characterized by early behavioral and personality changes and executive dysfunction [12], and primary progressive aphasia (PPA), associated with progressive deficits in language [13]. In particular, the agrammatic variant of PPA (avPPA) presents with slow, effortful speech, and grammar deficits, whereas the semantic variant of PPA (svPPA) begins with difficulty finding words, particularly nouns, and single-word comprehension deficits.

A family history of dementia is found in 25–50% of the FTD patients with microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT) and progranulin (GRN) mutations, and chromosome 9 open-reading-frame 72 (C9orf72) expansion as major pathogenetic determinants [14].

A few studies have suggested a link between sex and phenotypic presentation in FTD [15,16,17], and a higher female prevalence of GRN mutations in FTD has been reported [18]. However, these results are not conclusive, which prompted the present study, aimed at exploring sex influences on disease onset, cognitive and behavioral features, and survival and biological biomarkers of disease severity in a large, single-center cohort of FTD patients.

Methods

Participants

In the present study, patients fulfilling current clinical criteria for probable FTD [13, 19] were consecutively recruited at the Centre for Neurodegenerative Disorders, Department of Clinical and Experimental Sciences, University of Brescia, Italy, from July 2007 to July 2021.

All patients underwent a comprehensive evaluation of their past medical history, complete neurological examination, standardized neuropsychological assessment, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain.

In familial cases, based on the presence of at least one dementia case among first-degree relatives and early-onset sporadic cases, genetic screening for GRN, C9orf72, and MAPT was performed. Given the low frequency of MAPT mutations in Italy [20], we considered only the P301L mutation and we sequenced the entire MAPT gene only in selected cases.

In a subset of patients, cerebrospinal fluid analysis or PET amyloid was performed to exclude focal AD pathology, as previously reported [21]. FTD patients were followed over time and data on survival recorded.

Neuropsychological and behavioral assessment

The standardized neuropsychological assessment included the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), Trail-Making Test (part A and part B), letter and semantic fluencies, Token Test, Digit Span forward, Short Story Recall Test, and Rey Complex Figure (copy and recall) [22]. The level of functional independence was assessed with Basic Activities of Daily Living (BADL) [23].

Behavioral disturbances were rated by the Italian version of the Frontal Behavioral Inventory [24, 25]. Disease severity was measured by CDR Dementia Staging Instrument plus behavior and language domains from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center and Frontotemporal lobar degeneration modules – sum of boxes (CDR plus NACC FTLD—SOB) [26].

Neurofilament light (NfL) measurements

In a subgroup of patients (n = 188), the serum was collected to assess the concentrations of NfL. The serum was obtained by venipuncture, processed and stored in aliquots at − 80 °C according to standardized procedures. The serum NfL concentration was measured using a commercial NF-Light assay (Quanterix, Billerica, Massachusetts, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The lower limit of quantitation for serum NfL was 0.174 pg/ml. Measurements were carried out using a HD-X analyser (Quanterix, Billerica, Massachusetts, USA), and the operators were blinded to all clinical information. Quality control samples had mean intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation of < 8% and < 20%, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Continuous and categorical variables are reported as mean (± standard deviation) and n (%), respectively. Between-group differences in demographic and global neuropsychological measures were assessed using independent sample t test and chi-square’s test for continuous and categorical variables. Separate analyses of covariances (ANCOVAs) were conducted for each cognitive test and behavioral subitems, covarying for disease severity, assessed by CDR plus NACC FTLD – SOB. Differences in serum NfL were assessed with a one-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), corrected for age and disease severity. For comparisons of each cognitive test and FBI subitems, a correction for multiple comparisons was performed using the Benjamini–Hochberg False Discovery Rate (FDR).

Survival was calculated as the time from symptom onset to time of death or the last follow-up. A Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was conducted to compare overall survival between male and female patients. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant. Data analyses were carried out using SPSS 21.0 software.

Data availability

All study data, including study design, statistical analysis plan, and results, are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Results

Participants

In the present study, 531 FTD patients were consecutively recruited, namely 345 patients with bvFTD [12], 118 with avPPA, and 68 with svPPA [13].

The study group consisted of 258 women (mean age 66.4 ± 8.1 years old) and 273 men (mean age 65.4 ± 8.4 years old). No significant differences in demographic characteristics were observed between groups, with the exception of the younger age at disease onset for male FTD patients (p = 0.047) (see Table 1).

FTD-related pathogenic mutations were identified in 95 patients (n = 66 GRN mutations, n = 26 C9orf72 expansions, n = 3 MAPT mutations). There were no sex differences within the prevalence of pathogenic mutations.

The main finding of our study is that the bvFTD phenotype was more common in men (74%), whereas PPA in women (57%, p < 0.001).

Neuropsychological measures in female and male FTD patients

Men and women showed no differences in global disease severity, as measured with CDR plus NACC FTLD—SOB (see Table 2). Overall, men presented more frequently behavioral disturbances, whereas women had higher cognitive impairment when considering specific tasks.

We compared behavioral disturbances, assessed by the FBI scale, across the two groups. Men exhibited more personality/behavioral symptoms (FBI AB, p = 0.003), displaying higher scores in positive FBI subscales (FBI B, p < 0.001), with no differences in FBI A. In particular, looking at FBI subitems, men presented more severe apathy (1.6 ± 1.1 vs. 1.3 ± 1.1, p = 0.02), irritability (1.1 ± 1.0 vs. 0.8 ± 1.0, p = 0.006), poor judgment (0.9 ± 1.2 vs. 0.7 ± 1.0, p = 0.033), aggressivity (0.6 ± 0.9 vs. 0.3 ± 0.7, p = 0.008), and hypersexuality (0.3 ± 0.7 vs. 0.0 ± 0.3, p = 0.006), after correction for disease severity (see Fig. 1, p-values corrected for multiple comparisons).

Women reached lower scores, corrected for disease stage, in Trail Making Test parts A and B (104.5 ± 125.1 vs. 150.4 ± 156.0; 245.7 ± 153.9 vs. 311.5 ± 151.7, both p = 0.003), semantic fluency (25.1 ± 12.6 vs. 22.0 ± 12.0, p = 0.03), Short Story Recall Test (9.0 ± 4.7 vs. 6.8 ± 4.8, p = 0.003), and Rey Complex Figure, copy (25.8 ± 14.6 vs. 21.7 ± 10.9, p = 0.005) (see Table 2, p-values corrected for multiple comparisons).

Biological markers and survival

NfL concentration was not different between men and women (41.2 ± 30.6 pg/ml vs 47.7 ± 30.5 pg/ml, p = 0.167) and across FTD subtypes (bvFTD = 43.5 ± 42.9 pg/ml, avPPA = 45.5 ± 34.5 pg/ml, svPPA = 31.8 ± 14.8 pg/ml, p = 0.517). The survival, assesses by Kaplan-Meyer curve, was not statistically different between men and women (p = 0.645) (see Fig. 2).

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that sex influences clinical features in a wide cohort of FTD patients. Indeed, we found that bvFTD was more common in men, while women presented more frequently with PPA. The different prevalence of the two phenotypes between sex was confirmed by neuropsychological tests and assessment of behavioral disturbances. Despite a comparable general cognitive status, women performed worse in language tasks as well as in executive, visual attention, and visuospatial tests. On the opposite side, men showed a higher frequency of neurobehavioral disturbances, in particular apathy, irritability, poor judgment, aggressivity, and hypersexuality. These discrepancies were not influenced by disease stage nor by education. These observations confirm and expand the results of previous studies [15,16,17], and argue for a possible influence of sex in FTD as well, beyond the well-known effect in AD. The opposite prevalence of bvFTD and PPA might reflect differences in biological vulnerability between males and females.

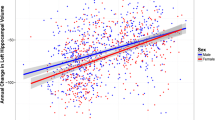

Considering that bvFTD usually involves the right hemisphere, whereas PPA the left hemisphere, we can hypothesize the presence of an asymmetric brain vulnerability to FTD between gender. Several studies have pointed to sex-related differences in brain asymmetry in physiological conditions [27,28,29], some indicating that males had greater rightward lateralization, while females had greater leftward lateralization [30]. Sex differences in brain organization are thought to underlie sex differences in motor and visuospatial skills, linguistic performance, and vulnerability to deficits following stroke and other focal lesions [31] as well as pathologies disrupting brain asymmetry, namely autism, and schizophrenia [32, 33]. Thus, this asymmetric susceptibility might also explain why men develop more frequently bvFTD and women PPA.

Neuropsychological profiles, especially language impairment, and behavioral disturbances found in our FTD cohort are in line to what was observed also in AD [34,35,36], thus suggesting that sex per se influences the clinical presentation regardless of the specific neurodegenerative disease. This hypothesis is further supported by the observation that also in patients affected by Parkinson’s disease, men present more frequently behavioral problems [37]. Exploring the biological factors, such as hormonal influence, may shed some light on FTD pathogenesis.

According to literature data, the FTD prevalence was found similar in men and women [11], although age at onset was lower in men than in women, independently from clinical phenotype or education. This result might be a sample bias, as studies in which only bvFTD were included observed comparable disease onset between men and women [17]. In addition, women might be more attentive than men to notice behavioral and cognitive symptoms of the spouse, thus leading to an earlier diagnosis of FTD in men. On the contrary, subtle language deficits with preserved functioning in daily life activities, without any behavioral disturbances in women may be underscored by male spouses and at the same time more socially acceptable, thus conditioning a later recognition of the disease.

Finally, we found that survival and NfL concentration were comparable between men and women, thus suggesting an equal aggressiveness, as already supported by previous studies [11, 38]. However, considering the longer life expectancy for women in the general population [39], this result could be interpreted as indirect evidence of more aggressive progression and worse prognosis in females affected by FTD.

We acknowledge that the present study entails some limits. Our results relied on a large clinical cohort; however, we are aware that they should be confirmed by international epidemiological studies and pathological confirmation would be needed. Moreover, we did not consider other potential factors influencing different clinical phenotypes between sex. Finally, clinical observations should be correlated with investigations exploring structural and functional neuroimaging.

In conclusion, we have reported relevant differences in FTD patients depending on sex, in particular concerning clinical presentation. This could suggest that sex is implicated in FTD pathogenesis; defining the sex-related mechanisms involved would be of crucial significance to understand the pathophysiology of the disease and to define tailored clinical approaches.

References

Eliot L (2011) The trouble with sex differences. Neuron 72:895–898. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NEURON.2011.12.001

Ruigrok ANV, Salimi-Khorshidi G, Lai MC et al (2014) A meta-analysis of sex differences in human brain structure. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 39:34–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NEUBIOREV.2013.12.004

Lotze M, Domin M, Gerlach FH, et al (2019) Novel findings from 2,838 Adult Brains on Sex Differences in Gray Matter Brain Volume. Sci Rep 9. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-018-38239-2

Oveisgharan S, Arvanitakis Z, Yu L et al (2018) Sex differences in Alzheimer’s disease and common neuropathologies of aging. Acta Neuropathol 136:887–900. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-018-1920-1

Mauvais-Jarvis F, Bairey Merz N, Barnes PJ et al (2020) Sex and gender: modifiers of health, disease, and medicine. Lancet (London, England) 396:565–582. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31561-0

Ferretti MT, Iulita MF, Cavedo E et al (2018) Sex differences in Alzheimer disease — The gateway to precision medicine. Nat Rev Neurol 14:457–469. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-018-0032-9

Nebel RA, Aggarwal NT, Barnes LL et al (2018) Understanding the impact of sex and gender in Alzheimer’s disease: A call to action. Alzheimers Dement 14:1171–1183. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JALZ.2018.04.008

Snyder HM, Asthana S, Bain L et al (2016) Sex biology contributions to vulnerability to Alzheimer’s disease: A think tank convened by the Women’s Alzheimer’s Research Initiative. Alzheimers Dement 12:1186–1196. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JALZ.2016.08.004

Altmann A, Tian L, Henderson VW, Greicius MD (2014) Sex modifies the APOE-related risk of developing Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol 75:563–573. https://doi.org/10.1002/ANA.24135

Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Haines JL et al (1997) Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease. A meta-analysis. APOE and Alzheimer Disease Meta Analysis Consortium. JAMA 278:1349–1356. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.278.16.1349

Onyike CU, Diehl-Schmid J (2013) The epidemiology of frontotemporal dementia. Int Rev Psychiatry 25:130–137. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2013.776523

Rascovsky K, Hodges JR, Knopman D et al (2011) Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain 134:2456–2477. https://doi.org/10.1093/BRAIN/AWR179

Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S et al (2011) Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology 76:1006–1014. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0B013E31821103E6

Borroni B, Padovani A (2013) Dementia: a new algorithm for molecular diagnostics in FTLD. Nat Rev Neurol 9:241–242. https://doi.org/10.1038/NRNEUROL.2013.72

Johnson JK, Diehl J, Mendez MF et al (2005) Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: demographic characteristics of 353 patients. Arch Neurol 62:925–930. https://doi.org/10.1001/ARCHNEUR.62.6.925

Rogalski E, Rademaker A, Weintraub S (2007) Primary progressive aphasia: relationship between gender and severity of language impairment. Cogn Behav Neurol 20:38–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNN.0B013E31802E3BAE

Illán-Gala I, Casaletto KB, Borrego-Écija S et al (2021) Sex differences in the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia: A new window to executive and behavioral reserve. Alzheimers Dement 17:1329–1341. https://doi.org/10.1002/ALZ.12299

Curtis AF, Masellis M, Hsiung GYR et al (2017) Sex differences in the prevalence of genetic mutations in FTD and ALS. Neurology 89:1633–1642. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000004494

de la Sablonnière JL, Tastevin M, Lavoie M, Laforce R (2021) Longitudinal changes in cognition, behaviours, and functional abilities in the three main variants of primary progressive aphasia: A literature review. Brain Sci 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/BRAINSCI11091209

Fostinelli S, Ciani M, Zanardini R et al (2018) The heritability of frontotemporal lobar degeneration: Validation of pedigree classification criteria in a Northern Italy Cohort. J Alzheimers Dis 61:753–760. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-170661

Borroni B, Benussi A, Archetti S et al (2015) Csf p-tau181/tau ratio as biomarker for TDP pathology in frontotemporal dementia. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 16:86–91. https://doi.org/10.3109/21678421.2014.971812

[Italian standardization and classification of Neuropsychological tests. The Italian Group on the Neuropsychological Study of Aging] - PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3330072/. Accessed 1 Mar 2022

Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW et al (1963) Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 185:914–919. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMA.1963.03060120024016

Alberici A, Geroldi C, Cotelli M et al (2007) The Frontal Behavioural Inventory (Italian version) differentiates frontotemporal lobar degeneration variants from Alzheimer’s disease. Neurol Sci 28:80–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10072-007-0791-3

Kertesz A, Davidson W, Fox H (1997) Frontal behavioral inventory: diagnostic criteria for frontal lobe dementia. Can J Neurol Sci 24:29–36. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0317167100021053

Miyagawa T, Brushaber D, Syrjanen J et al (2020) Utility of the global CDR ® plus NACC FTLD rating and development of scoring rules: Data from the ARTFL/LEFFTDS Consortium. Alzheimers Dement 16:106–117. https://doi.org/10.1002/ALZ.12033

Galaburda AM, LeMay M, Kemper TL, Geschwind N (1978) Right-left asymmetrics in the brain. Science 199:852–856. https://doi.org/10.1126/SCIENCE.341314

Toga AW, Thompson PM (2003) Mapping brain asymmetry. Nat Rev Neurosci 4:37–48. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1009

Hirnstein M, Hugdahl K, Hausmann M (2019) Cognitive sex differences and hemispheric asymmetry: A critical review of 40 years of research. Laterality 24:204–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/1357650X.2018.1497044

Tomasi D, Volkow ND (2012) Laterality patterns of brain functional connectivity: Gender effects. Cereb Cortex 22:1455–1462. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhr230

Kimura D (1999) Sex and cognition. 217

Baron-Cohen S, Knickmeyer RC, Belmonte MK (2005) Sex differences in the brain: implications for explaining autism. Science 310:819–823. https://doi.org/10.1126/SCIENCE.1115455

Narr KL, Thompson PM, Sharma T et al (2001) Three-dimensional mapping of gyral shape and cortical surface asymmetries in schizophrenia: Gender effects. Am J Psychiatry 158:244–255. https://doi.org/10.1176/APPI.AJP.158.2.244

Ott BR, Tate CA, Gordon NM, Heindel WC (1996) Gender differences in the behavioral manifestations of Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 44:583–587. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1532-5415.1996.TB01447.X

Mega MS, Cummings JL, Fiorello T, Gornbein J (1996) The spectrum of behavioral changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 46:130–135. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.46.1.130

Pusswald G, Lehrner J, Hagmann M et al (2015) Gender-specific differences in cognitive profiles of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: Results of the Prospective Dementia Registry Austria (PRODEM-Austria). J Alzheimers Dis 46:631–637. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-150188

Fernandez HH, Lapane KL, Ott BR, Friedman JH (2000) Gender differences in the frequency and treatment of behavior problems in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 15:490–496. https://doi.org/10.1002/1531-8257(200005)15:3%3c490::AID-MDS1011%3e3.0.CO;2-E

Roberson ED, Hesse JH, Rose KD et al (2005) Frontotemporal dementia progresses to death faster than Alzheimer disease. Neurology 65:719–725. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.WNL.0000173837.82820.9F

Ferretti MT, Martinkova J, Biskup E et al (2020) Sex and gender differences in Alzheimer’s disease: current challenges and implications for clinical practice: Position paper of the Dementia and Cognitive Disorders Panel of the European Academy of Neurology. Eur J Neurol 27:928–943. https://doi.org/10.1111/ENE.14174

Acknowledgements

AB was partially supported by the Airalzh-AGYR2020 and by Fondazione Cariplo, grant n° 2021-1516. HZ is a Wallenberg Scholar supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (#2018-02532), the European Research Council (#681712), Swedish State Support for Clinical Research (#ALFGBG-71320), the Alzheimer Drug Discovery Foundation (ADDF), USA (#201809-2016862), the AD Strategic Fund and the Alzheimer’s Association (#ADSF-21-831376-C, #ADSF-21-831381-C, and #ADSF-21-831377-C), the Olav Thon Foundation, the Erling-Persson Family Foundation, Stiftelsen för Gamla Tjänarinnor, Hjärnfonden, Sweden (#FO2019-0228), the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 860197 (MIRIADE), the European Union Joint Programme Neurodegenerative Disease Research (JPND2021-00694), and the UK Dementia Research Institute at UCL (UKDRI-1003). BB was supported by the RF-2018-12366665 grant (Italian Ministry of Health).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Brescia within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.P., A.A., A.B., and B.B. contributed to the conception and design of the study. M.P., A.A., I.L., A.B., Y.G., N.A., H.Z., B.K., and B.B. contributed to the acquisition and analysis of the data. M.P., A.A., A.B., and B.B. contributed to drafting the text and preparing the figures. All the authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, approved the final, submitted version of the manuscript, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

HZ has served at scientific advisory boards and/or as a consultant for Abbvie, Alector, Annexon, Artery Therapeutics, AZTherapies, CogRx, Denali, Eisai, Nervgen, Novo Nordisk, Pinteon Therapeutics, Red Abbey Labs, Passage Bio, Roche, Samumed, Siemens Healthineers, Triplet Therapeutics, and Wave; has given lectures in symposia sponsored by Cellectricon, Fujirebio, Alzecure, Biogen, and Roche; and is a co-founder of Brain Biomarker Solutions in Gothenburg AB (BBS), which is a part of the GU Ventures Incubator Program (outside submitted work).

Ethical approval and Informed consent

A written Informed consent was obtained from each subject. The work conforms to the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the ethics committee of our hospital.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pengo, M., Alberici, A., Libri, I. et al. Sex influences clinical phenotype in frontotemporal dementia. Neurol Sci 43, 5281–5287 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-022-06185-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-022-06185-7