Abstract

Background

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is characterized by phenotypical heterogeneity, partly resulting from demographic and environmental risk factors. Socio-economic factors and the characteristics of local MS facilities might also play a part.

Methods

This study included patients with a confirmed MS diagnosis enrolled in the Italian MS and Related Disorders Register in 2000–2021. Patients at first visit were classified as having a clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), relapsing–remitting (RR), primary progressive (PP), progressive-relapsing (PR), or secondary progressive MS (SP). Demographic and clinical characteristics were analyzed, with centers’ characteristics, geographic macro-areas, and Deprivation Index. We computed the odds ratios (OR) for CIS, PP/PR, and SP phenotypes, compared to the RR, using multivariate, multinomial, mixed effects logistic regression models.

Results

In all 35,243 patients from 106 centers were included. The OR of presenting more advanced MS phenotypes than the RR phenotype at first visit significantly diminished in relation to calendar period. Females were at a significantly lower risk of a PP/PR or SP phenotype. Older age was associated with CIS, PP/PR, and SP. The risk of a longer interval between disease onset and first visit was lower for the CIS phenotype, but higher for PP/PR and SP. The probability of SP at first visit was greater in the South of Italy.

Discussion

Differences in the phenotype of MS patients first seen in Italian centers can be only partly explained by differences in the centers’ characteristics. The demographic and socio-economic characteristics of MS patients seem to be the main determinants of the phenotypes at first referral.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic immune-mediated neurological disease affecting more than two million people in the world [1, 2]. In Italy, around 129,220 people are estimated to live with MS, with a prevalence of about 210 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, with the exception of Sardinia, where the prevalence is higher (390 cases per 100,000) [3]. MS is characterized by five major phenotypes, namely the clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), relapsing–remitting (RR), primary progressive (PP), progressive-relapsing (PR), and secondary progressive MS (SP) [4, 5]. The same risk factors, i.e., genetic patterns, tobacco smoking, exposure to air pollutants, viral infections, low vitamin D levels, and juvenile obesity [6, 7], also affect the type and severity of the disease. Other factors unrelated to demographic and clinical features, like the variability of contacts, diagnostic paths, and therapeutic capabilities, may also influence the MS phenotypes. A wide range of services and treatments are offered to people with MS, varying based on MS centers’ characteristics, geographic distribution, and socioeconomic conditions of the local populations [8].

Real-world observational studies, such as registers, provide important information on the history, course, and severity of MS, useful for public health aims and to complement clinical trial results. Increasing numbers of MS registers have been established in recent years, providing good opportunities for advance in MS research, pharmacovigilance, and sharing data among international MS data repositories [9, 10]. In Italy, the AISM (Associazione Italiana Sclerosi Multipla) — a powerful patients’ organization founded in 1968 — advocates for the rights of people with MS, supporting a network of local branches who collaborate with healthcare professionals and clinical centers. AISM endorsed the establishment of the Italian MS and Related Disorders Register which now includes a large cohort of people with MS and provides a descriptive picture of the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the disease, facilitating comparisons of socio-demographic, geographic, and clinical factors [11].

This study describes MS phenotypes at first visit, comparing differences in MS phenotypes across centers’ characteristics and location, and patients’ socio-demographic and clinical variables.

Material and methods

Data source

Data used for the present analysis were extracted from the Italian MS and Related Disorders Register, a nationwide database, sustained by a network of 161 MS centers and promoted in 2014, in continuity with the existing Italian MSDatabase Network [12]. The Italian Register now contains data on more than 72,000 exclusively registered patients, enrolled using a common minimum dataset, and this sample size represents approximately the 56% of Italian MS patients. During its first years, the Italian Register data were stored on a client server (iMed© software), but since 2017, a web-based tool has been developed, onto which all data have been gradually transferred (http://www.registroitalianosm.it). Data are centrally monitored to guarantee the quality of information and centers are periodically contacted with ad hoc queries on missing data or inconsistencies in the variables recorded. Data of the Italian Register are required to be updated every 6 months [11].

For the present study, we also retrieved information on the centers included in the Italian Register through a survey conducted in 2020. In case of missing information, the survey results were integrated with data from the 2018 Barometer of MS — a benchmarking tool published by AISM, to provide an accurate picture of MS management across health and social care systems in Italy [13]. The survey collected data on the type of center: organizational structure of the operating unit, number of patients treated, number of neurologists and nurses dedicated to MS patients, difficulties in access to disease-modifying treatments (DMT), beds dedicated to MS patients, and presence of formally recognized Diagnostic and Critical Pathways (Percorsi Diagnostico-Terapeutici Assistenziali — PDTA). We classified the areas where centers were located into five macro-areas, i.e., North-West (Piedmont, Valle d’Aosta, Liguria, Lombardy), North-East (Trentino-Alto Adige, Veneto, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Emilia-Romagna), Center (Tuscany, Umbria, Marche, Lazio), South (Abruzzo, Molise, Campania, Puglia, Basilicata, Calabria), and Islands (Sicily, Sardinia). We assigned to each center the quintile of deprivation index (DI) of the corresponding province, updated and revised on the basis of 2011 Italian census data [14, 15]. This index measures social and material deprivation in the presence of low educational level, unemployment, living in rental property, living in a crowded house, and living in a single-parent family. The DI was then grouped in three classes, I–II (low deprivation), III (moderate deprivation), and IV–V (high deprivation).

Study population

The study population is composed of all consecutive patients with a confirmed diagnosis of MS (according to McDonald 2001 criteria, and subsequent updates of 2010 and 2017 [16]) enrolled in 2000–2021. The MS phenotypes were defined through an algorithm, developed and validated according to Scientific Committee, considering date at onset, diagnosis, progression start, and relapse, together with the information reporting whether or not the onset of progression coincided with the date of onset. Dates were ordered from the earliest to the latest and, considering the temporal sequence, five disease phenotypes were so defined: CIS, PP, PR, RR, SP.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics are presented using summary statistics, as appropriate. We computed the odds ratio (OR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) for CIS, PP/PR, and SP phenotypes compared to the RR phenotype according to selected patients’ and centers’ characteristics, using univariate and multivariate, multinomial, multilevel logistic regression models including random effects for center. These models allowed to take into account for the hierarchical nature of the data (i.e., patients and clinicians are nested within hospitals). We also performed models including a further level for geographic regions that provided very similar results. Multivariate models were adjusted for age, sex, and time between disease onset and first visit. For statistical analyses we used the software SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

As of 31 May 2021, there were 72,283 patients in the Italian Register. We first excluded 30,166 patients enrolled before 2000 or with enrolment date missing and those not included in the minimum dataset (i.e., with neuromyelitis optic spectrum disorder or no McDonald-confirmed MS diagnosis, and incomplete/inconsistent information on relevant variables). We also excluded patients with only one visit, and those from centers that did not participate in the survey. A total of 35,243 patients from 106 centers were thus included in the present study (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Table 1 reports the baseline characteristics of the patients analyzed: two-third were female (67%); mean age was 33.4 years at the onset, and 36.2 years at the first visit; a median of 13 months passed between onset and first visit; about 80% had only one symptom at onset; median EDSS score at first visit was 2.4, with a median MS disease severity index of 4.7; most patients received an RR diagnosis, and about a quarter had a CIS diagnosis. The distribution of 5437 patients enrolled from 2000 and included in the minimum dataset (i.e., with a confirmed MS diagnosis and no incomplete/inconsistent information on relevant variables regarding diagnosis and visits) but not considered in the final cohort is presented in Supplementary Table 1. As compared to those included in our analyses, those patients were more frequently enrolled in 2015–2021, had a higher time between disease onset and first visit but a lower time between disease onset and diagnosis, and were more frequently under a DMT treatment.

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the study centers by geographic macro-areas, with the corresponding DI. More than half of the patients were attending North-West and South centers, where there were more participating centers (36 and 22, respectively). Centers in the South were in more deprived areas than North-West centers. About 19% of patients were in the Center and 15% in the Islands, both with a high DI. Finally, 11% of patients were attending North-East centers, where the DI was lowest. Supplementary Table 2 illustrates the characteristics of the 106 centers.

The disease phenotypes at first visit varied with patients and centers’ characteristics (Table 2). Females were less frequent among PP/PR and SP patients; age at first visit was older in PP/PR and SP patients. Time between disease onset and first visit was shorter for CIS, but longer for PP/PR and SP patients. The disease phenotypes were similar according to the centers’ characteristics, as geographical macro-areas (except for larger proportion of PP/PR phenotypes in the Islands and a smaller proportion in the South), number of patients followed, healthcare professionals dedicated, MS-dedicated beds, and access to DMT.

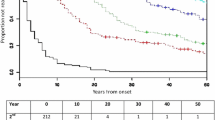

Table 3 gives the results of multivariate analysis for CIS, PP/PR, and SP phenotypes at first visit compared to RR phenotypes, according to selected patients’ and centers’ characteristics. The corresponding results of univariate analyses are given in Supplementary Table 3. The OR of presenting more advanced MS phenotypes, compared to the RR phenotype, significantly diminished over the years (OR = 0.74 of PP/PR for 2010–2014 and 2015–2021 vs 2000–2009, and OR = 0.50 of SP for 2015–2021 vs 2000–2009). Females were at significantly lower risk than males of PP/PR (OR = 0.47) or SP phenotype (OR = 0.62). Older age at first visit was associated with the risk of CIS (OR = 1.37 for ≥ 35 vs < 35 years), and particularly of PP/PR (OR = 9.21) and SP (OR = 4.53). The risk of a long interval between disease onset and first visit was lower for CIS phenotype (OR = 0.11 for ≥ 13 vs < 13 months), but higher for PP/PR (OR = 1.49) and particularly for SP (OR = 10.19). The probability of an SP phenotype was greater in the South (OR = 1.86 vs North-West) and a CIS in the North-East (OR = 1.64). No meaningful associations with MS phenotype were found for other centers’ characteristics or DI.

Discussion

This retrospective study of a large cohort of MS patients depicts the distribution of MS phenotypes at first visit comparing different geographic macro-areas, patients’ socio-demographic features, and the characteristics of referral centers. The demographic and socio-economic characteristics of MS patients seem to be the main determinants of the phenotypes at first referral, while differences in the phenotypes can be only partly explained by differences in the centers’ structures, capabilities, and patient loads.

PP/PR and SP patients were older at first visit than CIS ones. This agrees with previous studies reporting that these disease variants — whether or not following an RR course — tend to occur at an older age, preferably in men [17].

We found that presentation with advanced MS phenotype at referral centers tended to decline over time. This is not unexpected because patients are increasingly referred by local neurologists to an MS center where they can receive drugs that cannot be administered elsewhere. The time between disease onset and first visit was longer in PP/PR and SP phenotypes, and this is a diagnostic challenge for these patients, who are also older and more likely to be female. Greater attention is needed in intercepting these late-onset MS cases considering also socio-cultural and environmental factors in long MS [18, 19].

The characteristics of MS centers, such as the number of patients followed, number of neurologists and nurses, access to DMT, beds dedicated, and presence of a PDTA, did not appear related to the disease phenotype. This could be the result of a multidisciplinary approach (confirmed in the majority of centers) and the contribution of the AISM which prompts the collection of epidemiological data as well as continuous exchange of experience and information among centers [8]. Moreover, the long history of data sharing through the Italian Register, started in 2010, has favored a standardization of diagnostic and treatment practices among centers [11, 12]. Although formally incorporated within their respective hospitals, MS centers in Italy historically form part of a broader network committed to ensuring all people with MS receive the appropriate lengthy care. The network permits communication and supports high-quality care within and across regions and over time. It also helps contrast the disparities in health systems [20].

Regarding the availability of DMT, we are aware that more than 50% of the centers reported difficulties in the access, mainly depending on the different reimbursement policies that each regional health service establishes. This shows the importance of a data collected through a Register with a national representativeness, which can contribute to the debate on the reimbursement of new, more effective therapies even in the early stages of the disease. Moreover, the support of a large patient association involved in all the phases of the Register can lead to significant future improvements.

Our results show more CIS phenotypes in the North-East and Center and more SP in Southern regions. The predominance of CIS in the North can be explained by the prompter access of patients at the start of symptoms to one of the MS centers widely distributed over this area, leading them to earlier diagnosis of the disease. The larger number of SP MS in the South compared to the North of Italy is harder to explain, except that most patients with MS in the South are referred to the few centers of excellence, and the distribution of DI is different.

The study has some strengths. We investigated a large nationwide sample of people with MS. As patients are followed in tertiary centers, we expect that the diagnosis is correct and management of the disease is appropriate. Then, the network of centers in the Italian Register forms the basis for standardized and comparable data collection. Moreover, real-world data like that provided by the MS registers allow assessment of the heterogeneity of the setting, centers’ and patients’ characteristics within national and international geographic realities [21, 22].

However, the study also has some limitations. First, our Register does not represent all Italian centers where SM patients can be diagnosed and followed. All regions are represented in the Register but not all the MS centers. Indeed, North-West and Southern centers recorded about 40% of cases, leaving only 20% in the Center. Territorial distribution of Centers also varies in the Italian macro-areas and can be explained by the different rates of establishment and growth of new centers according to local priorities, as well as the development of some large referral centers in southern regions.

Second, selection bias cannot be excluded; however, the analysis of only MS patients enrolled since 2000 reduced the number of excluded cases and does not invalidate the results of the analyzed cohort. Patients excluded from the present analysis had indeed few differences compared to those included in the analysis (Supplementary Table 1). In addition, milder forms of the disease might not have been registered as managed by general neurologists in the community, and we do know that more severe MS forms are not followed in a hospital setting.

Third, the data quality remains one of the weak points of multicenter registers. We are addressing this issue by monitoring the centers every 2 months and sending out periodic detailed reports to the centers. A network of research assistants is engaged in more than 90 centers collaborating with local neurologists both in the input of new cases and in the update of data, especially as regards the historical cohort. Eight quality indicators have been developed and periodically communicated to the centers, and other 5 indicators are currently under revision and will soon be implemented (11). In conclusion, our findings indicate that differences in the phenotypes of people with MS who are seen first in Italian centers can be only partly explained by differences in the centers’ structures, capabilities, and patient loads. However, the socio-economic context of the local population might help explain differences in the proportions of patients at the two extremes of the disease spectrum. However, the overall picture is getting better, as shown by the trends of the disease variants from the old to the more recent periods. To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies where data deriving from MS registers have been specifically used to evaluate the possible relationships between the characteristics of the MS centers and the phenotype of the MS patients. We therefore agree with Magyari [9, 23] and Allen-Philbey [24] that population-based registries and integrated databases are crucial for an accurate description of both the changing prognosis of MS and the different characteristics of the various MS phenotypes.

Data availability

The dataset analyzed for this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Reich DS, Lucchinetti CF, Calabresi PA (2018) Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 378:169–180. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1401483

GBD (2016) Multiple Sclerosis Collaborators (2019) Global, regional, and national burden of multiple sclerosis 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol 18(3):269–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30443-5

AISM. Barometro della Sclerosi Multipla 2021: Dall’Agenda della sclerosi multipla 2020 all’Agenda della sclerosi multipla 2025. (2021), 24. https://aism.it/sites/default/files/Barometro_della_Sclerosi_Multipla_2021.pdf (accessed 13 April 2022).

Lublin FD (2014) New multiple sclerosis phenotypic classification. Eur Neurol 72(Suppl 1):1–5. https://doi.org/10.1159/000367614

Lublin FD, Coetzee T, Cohen JA, Marrie RA, Thompson AJ (2020) International Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials in MS The 2013 clinical course descriptors for multiple sclerosis: a clarification. Neurology 94(24):1088–1092. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000009636

Amato MP, Derfuss T, Hemmer B, Liblau R, Montalban X, SoelbergSørensen P, Miller DH, 2016 ECTRIMS Focused Workshop Group (2018) Environmental modifiable risk factors for multiple sclerosis: report from the 2016 ECTRIMS focused workshop. Mult Scler 24(5):590–603. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458516686847

Puthenparampil M, Perini P, Bergamaschi R, Capobianco M, Filippi M, Gallo P (2021) Multiple sclerosis epidemiological trends in Italy highlight the environmental risk factors. J Neurol. Sep 27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-021-10782-5.

Soelberg Sorensen P, Giovannoni G, Montalban X, Thalheim C, Zaratin P, Comi G (2019) The multiple sclerosis care unit. Mult Scler 25(5):627–636. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458518807082

Magyari M, Joensen H, Laursen B, Koch-Henriksen N (2021) The Danish Multiple Sclerosis Registry. Brain Behav 11(1):e01921. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1921

Ohle LM, Ellenberger D, Flachenecker P, Friede T, Haas J, Hellwig K, Parciak T, Warnke C, Paul F, Zettl UK, Stahmann A (2021) Chances and challenges of a long-term data repository in multiple sclerosis: 20th birthday of the German MS registry. Sci Rep 11:13340. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92722-x

Trojano M, Bergamaschi R, Amato MP, Comi G, Ghezzi A, Lepore V, Marrosu MG, Mosconi P, Patti F, Ponzio M, Zaratin P, Battaglia MA (2019) Italian Multiple Sclerosis Register Centers Group. The Italian Multiple Sclerosis Register. Neurol Sci 40(1):155–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-018-3610-0

Trojano M, Pellegrini F, Paolicelli D, Fuiani A, Zimatore GB, Tortorella C, Simone IL, Patti F, Ghezzi A, Zipoli V, Rossi P, Pozzilli C, Salemi G, Lugaresi A, Bergamaschi R, Millefiorini E, Clerico M, Lus G, Vianello M, Avolio C, Cavalla P, Lepore V, Livrea P, Comi G, Amato MP Italian Multiple Sclerosis Database Network (MSDN) Group (2009) Real-life impact of early interferon beta therapy in relapsing multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 66(4):513-20.https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.21757

Barometro AISM (2019) https://agenda.aism.it/2021/#precedenti [Access 22 December 2021]

Caranci N, Biggeri A, Grisotto L, Pacelli B, Spadea T, Costa G (2010) L’indice di deprivazione italiano a livello di sezione di censimento: definizione, descrizione e associazione con la mortalità. Epidemiol Prev 34:167–176

Rosano A, Pacelli B, Zengarini N, Costa G, Cislaghi C, Caranci N (2020) Update and review of the 2011 Italian deprivation index calculated at the census section level. Epidemiol Prev 44(2–3):162–170. https://doi.org/10.19191/EP20.2-3.P162.039

Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F, Carroll WM, Coetzee T, Comi G, Correale J, Fazekas F, Filippi M, Freedman MS, Fujihara K, Galetta SL, Hartung HP, Kappos L, Lublin FD, Marrie RA, Miller AE, Miller DH, Montalban X, Mowry EM, Sorensen PS, Tintoré M, Traboulsee AL, Trojano M, Uitdehaag BMJ, Vukusic S, Waubant E, Weinshenker BG, Reingold SC, Cohen JA (2018) Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. The Lancet Neurology 17(2):162–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30470-2

Miller DH, Leary SM (2007) Primary-progressive multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 6(10):903–912. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70243-0

Eccles A (2019) Delayed diagnosis of multiple sclerosis in males: may account for and dispel common understandings of different MS ‘types.’ Br J Gen Pract 69(680):148–149. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp19X701729

Ghiasian M, Faryadras M, Mansour M, Khanlarzadeh E, Mazaheri S (2021) Assessment of delayed diagnosis and treatment in multiple sclerosis patients during 1990–2016. Acta Neurol Belg 121(1):199–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13760-020-01528-7

Rethinking MS in Europe – European Brain Council (EBC) (2021) https://www.braincouncil.eu/projects/rethinkingms/ (Access 22 December 2021)

Cohen JA, Trojano M, Mowry EM, Uitdehaag BM, Reingold SC, Marrie RA (2020) Leveraging real-world data to investigate multiple sclerosis disease behavior, prognosis, and treatment. Mult Scler 26(1):23–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458519892555

Glaser A, Stahmann A, Meissner T, Flachenecker P, Horáková D, Zaratin P, Brichetto G, Pugliatti M, Rienhoff O, Vukusic S, de Giacomoni AC, Battaglia MA, Brola W, Butzkueven H, Casey R, Drulovic J, Eichstädt K, Hellwig K, Iaffaldano P, Ioannidou E, Kuhle J, Lycke K, Magyari M, Malbaša T, Middleton R, Myhr KM, Notas K, Orologas A, Otero-Romero S, Pekmezovic T, Sastre-Garriga J, Seeldrayers P, Soilu-Hänninen M, Stawiarz L, Trojano M, Ziemssen T, Hillert J, Thalheim C (2019) Multiple sclerosis registries in Europe - an updated mapping survey. Mult Scler Relat Disord 27:171–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2018.09.032

Magyari M, Sorensen PS (2019) The changing course of multiple sclerosis: rising incidence, change in geographic distribution, disease course, and prognosis. Curr Opin Neurol 32(3):320–326. https://doi.org/10.1097/WCO.0000000000000695

Allen-Philbey K, Middleton R, Tuite-Dalton K, Baker E, Stennett A, Albor C, Schmierer K (2020) Can we improve the monitoring of people with multiple sclerosis using simple tools, data sharing, and patient engagement? Front Neurol 11:464. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.00464

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Guya Sgaroni for organizational assistance, and Judith Baggott for editorial assistance. The authors thank for their valuable local activities contribution the Research Assistance: Beatrice Biolzi, Daniele Dell’Anna, Sonia Di Lemme, Chiara Di Tillio, Grazia Galleri, Federica Martini, Cristiana Morano, Ornella Moreggia, Placido Nicolosi, Silvia Perugini, Chiara Raimondi, Antonino Rallo, Ilaria Rossi, Graziana Scialpi.

Centers Group, project responsible (Clinical Center): Aguglia U (Ambulatorio SM-Grande Ospedale Metropolitano Bianchi Melacrino Morelli, Reggio Calabria); Amato MP (Dipartimento NEUROFARBA, Università di Firenze, Centro SM-AUO Careggi, Firenze); Ancona AL (Ambulatorio Malattie Demielinizzanti, Divisione Neurologica-Ospedale San Jacopo, Pistoia); Ardito B (Centro SM, UOC di Neurologia-Ospedale della Murgia Fabio Perinei, Altamura); Avolio C (Centro Interdipartimentale Malattie Demielinizzanti-AOU Ospedali Riuniti, Foggia); Balgera R (Centro SM, Divisione di Neurologia-AO A. Manzoni, Lecco); Banfi P (Centro SM, Ambulatorio Malattie Demielinizzanti-Ospedale di Circolo e Fondazione Macchi, Varese); Barcella V (Centro Provinciale SM-ASST Papa Giovanni XXIII, Bergamo); Barone P (Divisione di Neurologia-AO San Giovanni di Dio, Salerno); Bellantonio P (Centro SM-IRCCS Neuromed, Pozzilli); Berardinelli A (UO Neuropsichiatria Infantile-IRCCS Fondazione Mondino, Pavia); Bergamaschi R (SS Sclerosi Multipla-IRCCS Fondazione Istituto Neurologico Nazionale C. Mondino, Pavia); Bertora P (Centro SM, UO Neurologia-ASST FBF Sacco P.O. Luigi Sacco, Milano); Bianchi M (Reparto di Neurologia-Ospedale di Esine, Esine); Bramanti P (IRCCS Centro Neurolesi Bonino Pulejo, Messina); Brescia Morra V (Centro Regionale SM-AOU Policlinico Federico II, Napoli); Brichetto G (Servizio Riabilitazione AISM Liguria, Genova); Brioschi AM (Istituto Auxologico Italiano IRCCS-Istituto Scientifico Ospedale San Giuseppe e Ambulatorio, Verbania); Buccafusca M (Centro SM-AOU Policlinico San Martino, Messina); Bucello S (Ospedale Muscatello, Augusta); Busillo V (UO di Neurologia, Centro Diagnosi e Terapia SM-Ospedale Maria SS. Addolorata, Eboli); Calchetti B (Centro Aziendale SM, UO Neurologia-Ospedale San Donato, Arezzo); Cantello R (Centro SM, Clinica Neurologica Dip di Medicina Traslazionale-Università del Piemonte Orientale, Novara); Capobianco M (Centro riferimento Regionale SM (CRESM), SCDO Neurologia-AUO San Luigi Gonzaga, Orbassano); Capone F (Centro SM, UOC Neurologia-Policlinico Universitario Campus Bio-Medico, Roma); Capone L (Centro Clinico Malattie Demielinizzanti dell’ASL di Biella-Ospedale degli Infermi, Biella); Cargnelutti D (SOC Neurologia, Day Hospital-ASUIUD P.O. S. Maria della Misericordia, Udine); Carrozzi M (SC di Neuropsichiatria Infantile-Istituto per l’Infanzia Burlo Garofolo, Trieste); Cartechini E (Centro SM, UOC Neurologia-Ospedale di Macerata, Macerata); Cavaletti G (Centro di Neuroimmunologia-ASST Monza e Brianza Ospedale San Gerardo, Monza); Cavalla P (Centro SM Neurologia 1 DU-AOU Città della Salute e della Scienza, Torino); Celani MG (Servizio Malattie Demielinizzanti, SC di Neurofisiopatologia-AO di Perugia, Perugia); Clerici R (Centro ad Alta Specializzazione Diagnosi e Cura SM-Ospedale Generale di Zona Valduce, Como); Clerico M (SCDU Neurologia 1-AOU San Luigi Gonzaga, Orbassano); Cocco E (Centro Regionale Diagnosi e Cura Sclerosi Multipla-ASL 8 P.O. Biraghi, Cagliari); Confalonieri P (Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, Milano); Coniglio MG (Centro SM-P.O. Madonna delle Grazie, Matera); Conte A (Centro Clinico Policlinico Umberto I, Università La Sapienza, Roma); Corea F (Neurologia Centro SM-Ospedale San Giovanni Battista, Foligno); Cottone S (Centro SM-Ospedale ARNAS Civico di Cristina Benfratelli, Palermo); Crociani P (Centro SM, UO Neurologia-Fondazione IRCCS Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza, San Giovanni Rotondo); D’Andrea F (Centro SM, UO Neurologia-Casa di Cura Villa Serena, Pescara); Danni MC (Centro SM, Clinica Neurologica-Ospedali Riuniti di Ancona, Ancona); De Luca G (Centro SM, Clinica Neurologica-Policlinico SS. Annunziata, Chieti); de Pascalis D (Centro Regionale Diagnosi e Cura SM e Malattie Demielinizzanti-Ospedale Sant’Eugenio, Roma); De Riz M (Centro SM-Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milano); De Robertis F (Divisione di Neurologia-Ospedale Vito Fazzi, Lecce); De Rosa G (Centro SM, Divisione di Neurologia-ASL TO4 Ospedale Civile, Ivrea); De Stefano N (Ambulatorio SM, UOSA Malattie Neurodegenerative e Demielinizzanti-AOU Senese, Siena); Della Corte M (SC Neurologia, Dip di Neuroscienze e Riabilitazione-AORN Santobono Pausilipon, Napoli); Di Sapio A (Centro SM-Ospedale Regina Montis Regalis, Mondovì); Docimo R (Centro SM-P.O. San Giuseppe Moscati, Aversa); Falcini M (Centro SM, Uo di Neurologia-Ospedale di Prato, Prato); Falcone N (Centro SM-Ospedale Belcolle, Viterbo); Fermi S (UO Neurologia-Ospedale Maggiore, Lodi); Ferraro E (Centro SM-PO San Filippo Neri ASL Roma 1, Roma); Ferrò MT (Neuroimmunologia, Centro Provinciale Diagnosi e Terapia SM-ASST di Crema, Crema); Fortunato M (Ambulatorio Malattie Demielinizzanti, UOC Neurologia-Ospedale Civile, Conegliano Veneto); Foschi M (Ambulatorio SM, UO Neurologia-Ospedale Santa Maria delle Croci AUSL Romagna, Ravenna); Gajofatto A (Clinica Neurologica, Dip di Neuroscienze Biomedicina e Movimento-Policlinico G.B. Rossi, Verona); Gallo A (Centro SM Divisione di Neurologia-Università degli Studi della Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, Napoli); Gallo P (CeSMuV Regione Veneto, Dip di Neuroscienze DNS-AOU Università degli Studi di Padova, Padova); Gatto M (Centro Malattie Demielinizzanti-Ospedale Regionale F. Miulli, Acquaviva delle Fonti); Gazzola P (SC Neurologia-Ospedale P. Antero Micone ASL 3 Genovese, Genova); Giordano A (SC Provinciale di Neurologia-ASP Ragusa P.O. R. Guzzardi, Ragusa); Granella F (Centro SM-AUO di Parma, Parma); Grasso MF (Centro SM, SC Neurologia-ASO S. Croce e Carle, Cuneo); Grasso MG (Centro SM-Fondazione Santa Lucia, Roma); Grimaldi LME (Centro SM-Fondazione Istituto G. Giglio, Cefalù); Iaffaldano P (Centro SM, Dipartimento di Scienze Mediche di Base ed Organi di Senso, Università di Bari, Bari); Imperiale D (Centro SM, Divisione di Neurologia-Ospedale Maria Vittoria, Torino); Inglese M (Centro Studio e Cura Sclerosi Multipla e Malattie Demielinizzanti, DiNOGMI-Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, Genova); Iodice R (UOC Neurologia e Centro per l’Epilessia-Università Federico II, Napoli); Leva S (Centro SM, Dipartimento di Neuroscienze-ASST Ovest Milanese, Legnano); Luezzi V (Dip di Neuroscienze Umane, Unità di Neuropsichiatria Infantile-Università La Sapienza, Roma); Lugaresi A (UOSI Riabilitazione Sclerosi Multipla-IRCCS ISNB, Bologna); Lus G (Centro Clinico Sclerosi Multipla, II Clinica Neurologica-II Università di Napoli, Napoli); Maimone D (Centro SM-Ospedale Garibaldi-Nesima, Catania); Mancinelli L (Centro SM, UO Neurologia-Ospedale Bufalini, Cesena); Maniscalco GT (Centro Regionale Diagnosi e Teparia Sclerosi Multipla-Napoli); Marfia GA (UOSD Sclerosi Multipla-Policlinico Universitario Tor Vergata, Roma); Marini B (UOC Neurologia-ULSS 2 Marca Trevigiana Regione Veneto Ospedale San Giacomo Apostolo, Castelfranco Veneto); Marson A (Neurologia-ASL TO4 Ospedale di Chivasso, Chivasso); Mascoli N (Centro SM, UO Neurologia-ASST Lariana Ospedale S. Anna, Como); Massacesi L (Centro riferimento regionale trattamento SM, Univ. Di Firenze-Dipartimento Neuroscienze AOU Careggi, Firenze); Melani F (UOC Neurologia Pediatrica-AOU Meyer, Firenze); Merello M (Divisione di Neurologia-Ospedale Mellino, Chiari); Meucci G (Ambulatorio SM, UO Neurologia e Neurofisiopatologia-Spedali Riuniti, Livorno); Mirabella M (UO Sclerosi Multipla-Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS, Roma); Montepietra S (Centro SM, UOC Neurologia-AO Santa Maria Nuova AUSL di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia); Nasuelli D (Ambulatorio SM-ASST della Valle Olona P.O. di Saronno, Saronno); Nicolao P (Reparto di Neurologia-ULSS 1 Dolomiti, Ospedale di Feltre, Feltre); Passantino F (Divisione di Neurologia-Azienda Ospedaliera SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo, Alessandria); Patti F (Centro SM-AOL Policlinico Vittorio Emanuele, Università di Catania, Catania); Peresson M (Centro Clinico SM-Ospedale Fatebenefratelli San Pietro, Roma); Pesci I (Centro SM, UOC Neurologia-AUSL di Parma Ospedale Di Vaio, Fidenza); Piantadosi C (Centro SM-AO San Giovanni Addolorata, Roma); Piras ML (Centro Diagnosi Cura e Ricerca Sclerosi Multipla-Ospedale San Francesco USL 3, Nuoro); Pizzorno M (Centro SM, Divisione di Neurologia-Ospedale S. Paolo, Savona); Plewnia K (Centro SM, UOC Neurologia-Ospedale Misericordia, Grosseto); Pozzilli C (Centro SM-Università La Sapienza Policlinico Sant'Andrea, Roma); Protti A (Centro SM, Dipartimento di Neurologia-ASST Grande Ospedale Metropolitano Niguarda, Milano); Quatrale R (Ambulatorio SM, Divisione di Neurologia-Ospedale dell’Angelo, Mestre); Realmuto S (Centro Riferimento regionale Malattie Neurologiche a Patogenesi Immunitaria-AOOR Villa Sofia-Cervello, Palermo); Ribizzi G (UO Neurologia, Dip. Neuroscienze e Organi di Senso-Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, Genova); Rinalduzzi S (Centro SM, UO di Neurologia-Ospedale San Camillo de Lellis, Rieti); Rini A (Centro SM-Ospedale A. Perrino, Brindisi); Romano S (CENTERS Centro Neurologico Terapie Sperimentali-Università La Sapienza AO Sant’Andrea, Roma); Romeo M (Centro SM-Ospedale San Raffaele, Milano); Ronzoni M (Centro SM-ASST Rhodense, Garbagnate Milanese); Rossi P (Ambulatorio SM e Malattie Demielinizzanti del SNC, UOC Neurologia-Ospedale San Bassiano, Bassano del Grappa); Rovaris M (Centro SM-IRCCS Fondazione Don Carlo Gnocchi, Milano); Salemi G (Centro Diagnosi e Cura SM e Malattie Demielinizzanti, Dip Emergenza e Neuroscienze-Università di Palermo, Palermo); Santangelo G (Centro Regionale SM in età evolutiva-Ospedale Pediatrico G. Di Cristina ARNAS Civico, Palermo); Santangelo M (UOC Neurologia-AUSL Modena Ospedale di Carpi, Carpi); Santuccio G (Reparto di Neurologia-ASST della Valtellina e Alto Lario Sedi di Sondrio e Sondalo, Sondrio); Sarchielli P (Centro Malattie Demielinizzanti-Ospedale Santa Maria della Misericordia, Perugia); Sinisi L (Centro SM, UOC Neurologia-Ospedale San Paolo ASL Napoli 1 Centro, Napoli); Sola P (Centro Malattie Demielinizzanti, Dipartimento di Neuroscienze-AUO/OCSAE Università di Modena e Reggio Emilia, Modena); Solaro C (Dipartimento di Riabilitazione-CRRF Monsignor Luigi Novarese, Moncrivello); Spitaleri D (Centro SM, UOC Neurologia-AORN San G. Moscati, Avellino); Strumia S (Ambulatorio SM dell’UO di Neurologia-Sede di Forlì AUSL della Romagna, Forlì); Tassinari T (Centro SM, SC Neurologia-Ospedale Santa Corona, Pietra Ligure); Tonietti S (Centro SM-Ospedale San Carlo ASST Santi Paolo e Carlo, Milano); Tortorella C (Centro SM-AO San Camillo Forlanini, Roma); Totaro R (Centro Malattie Demielinizzanti, Clinica Neurologica-Ospedale San Salvatore, L’Aquila); Tozzo A (Dip di Neuroscienze Pediatriche-Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, Milano); Trivelli G (Ambulatorio SM, Neurologia-ASL 4 Chiavarese, Lavagna); Ulivelli M (UOC Neurologia e Neurofisiologia Clinica- Università degli Studi di Siena, Siena); Valentino P (Centro SM-Policlinico Universitario Campus Germaneto-Catanzaro); Venturi S (Ambulatorio SM-E.O. Ospedale Galliera, Genova); Vianello M (Centro SM, UO Neurologia-Ospedale Ca’ Foncello, Treviso); Zaffaroni M (Centro SM-ASST della Valle Olona Ospedale di Gallarate, Gallarate); Zarbo R (Centro Diagnosi e Cura SM-AOU di Sassari, Sassari).

Scientific Committee of the Italian Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders Register: Maria Trojano (Dipartimento Scienze Mediche di Base, Neuroscienze ed Organi di Senso, Università degli Studi Aldo Moro, Bari); Mario Alberto Battaglia (Fondazione Italiana Sclerosi Multipla, Genova); Marco Capobianco (Centro Di Riferimento Regionale Per La SM (CRESM)—SCDO Neurologia—AOU San Luigi, Orbassano); Maura Pugliatti (Centro Di Servizio E Ricerca Sulla Sclerosi Multipla AOU Di Ferrara, Ferrara); Monica Ulivelli (UOC Neurologia e Neurofisiologia Clinica—Università degli Studi di Siena, Siena); Paola Mosconi (Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri IRCCS, Milano); Claudio Gasperini (UOC di Neurologia e Neurofisiopatologia Azienda Ospedaliera S. Camillo-Forlanini, Roma); Francesco Patti (Centro Sclerosi Multipla AOU Policlinico Vittorio Emanuele, Catania); Maria Pia Amato (Centro Sclerosi Multipla AOU Careggi, Firenze); Roberto Bergamaschi (Centro di Ricerca Sclerosi Multipla, IRCCS Fondazione Istituto Neurologico C. Mondino, Pavia); Giancarlo Comi (Università Vita Salute San Raffaele, Casa di Cura del Policlinico, Milano).

Funding

The Italian MS and Related Disorders Register is supported by the Italian MS Association representing people with multiple sclerosis (AISM), with its Foundation (FISM). The Mario Negri Institute IRCCS received funds from FISM as a Technical Methodological Structure of the Italian MS and Related Disorders Register. FISM was directly involved in all the phases of the project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Ettore Beghi, Roberto Bergamaschi, Vito Lepore, and Paola Mosconi designed the study protocol; Cristina Bosetti, Claudia Santucci, and Michela Ponzio analyzed the database and gave substantial contributions to the interpretation of findings; Paola Mosconi, Cristina Bosetti, and Ettore Beghi drafted the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

RB as an advisory board member reports, speakers’ honoraria, travel support, research grants, consulting fees, and stock support from Almiral, Bayer, Biogen, Merck, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi, and Teva. EB reports financial support for research from the Italian Ministry of Health, the American ALS Association, Swedish Orphan Biovitrum, and personal compensation from Arvelle Therapeutics for advisory board membership, outside the present study. PM, VL, CB, and CS report no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

The Italian MS and Related Disorders Register was approved by the Ethics Committee of the coordinating center (University of Bari, reference numbers 0055587 and 0052885), and by the local ethics committees of all participant centers. The protocol for this analysis was discussed and approved by the Scientific Committee of the Italian Register. Each person enrolled signed written informed consent. In some centers where data were collected before the Italian Register was set up, retrospective information was included without informed consent when the patient was not traceable because of death, transfer or other reasons, according to local laws and regulations. This analysis does not contain any individual person’s information.

Consent for publication

All the authors meet the journal’s criteria for authorship and have read and approved the article.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bergamaschi, R., Beghi, E., Bosetti, C. et al. Do patients’ and referral centers’ characteristics influence multiple sclerosis phenotypes? Results from the Italian multiple sclerosis and related disorders register. Neurol Sci 43, 5459–5469 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-022-06169-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-022-06169-7