Abstract

Background

There is a lack of studies of Huntington’s disease (HD) in immigrants.

Objective

To study the association between country of birth and incident HD in first-generation immigrants versus Swedish-born individuals and in second-generation immigrants versus Swedish-born individuals with Swedish-born parents.

Methods

Study populations included all adults aged 18 years and older in Sweden, i.e., in the first-generation study 6,042,891 individuals with 1034 HD cases and in the second-generation study 4,860,469 individuals with 1001 cases. HD was defined as having at least one registered diagnosis of HD in the National Patient Register. The incidence of HD in different first-generation immigrant groups versus Swedish-born individuals was assessed by Cox regression, expressed as hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). The models were stratified by sex and adjusted for age, geographical residence in Sweden, educational level, marital status, and neighborhood socioeconomic status.

Results

Mean age-standardized incidence rates per 100,000 person-years were for all Swedish-born 0.82 and for all foreign born 0.53 and for all men 0.73 and for all women 0.81, with the highest incidence rates for the group 80–84 years of age. After adjusting for potential confounders, the HRs were lower in women in the first- and second-generation, i.e., 0.49 (95% CI 0.36–0.67) and 0.63 (95% 0.45–0.87), respectively, and also among women from Finland or with parents from Finland.

Significance

In general, the risk of HD was lower in first-generation and second-generation immigrant women but not among male immigrants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Huntington’s disease (HD) is an autosomal dominant inherited neurodegenerative disease first described in 1872. HD is characterized most of all by progressive motor, cognitive, and psychiatric symptoms [1]. The disease is caused by an expanded CAG repeat within the Huntington’s gene on chromosome 4 [2, 3], with a mean onset of symptoms at around 40 years of age, but with also earlier as well as later onset [1].

There are large differences between different regions of the world, with the lowest recorded prevalence rates of 1 or below per 100,000 in some sub-Saharan African and Asian countries [4]. In Caucasian populations, prevalence rate is estimated to 5.7 per 100,000 in Europe, North America, and Oceania [5] and up to 10 per 100,000 in Western Europe, North America, and Australia [4]. Furthermore, HD is regarded to be more common in people of north European origin [1]. In the UK, the prevalence of identified cases of HD in individuals aged 21 years and above has increased between 1990 and 2010 from 5.4 to 12.3 per 100,000, mostly in older ages [6]. The prevalence rate among men and women in this study was similar, with a mean average prevalence in 1990 and 2010 of men 9.4 and of women 10.4 per 100,000 and with the highest prevalence in the ages 51–60 years [6]. In Canada, the estimated prevalence in 2012 was 13.7/100,000 in the general population and 17.2 in the Caucasian population [7]. Mean age of patients was 56.9 years, mean age of onset of neurological symptoms was 47.9 years, and mean age at diagnosis was 49.7 years.

As regards incidence studies, studies from Europe, North America, and Australia have shown incidence rates between 0.47 and 0.69 per 100,000 [5]. In the UK, the incidence rate was found to be constant between 1990 and 2010 with a rate 0.72 per 100,000 [8]. In Sweden, the annual average incidence rate differs between different regions, with 1.5 per 100,000 in Jämtland in northern Sweden, 0.44 in Region Uppsala in the middle of Eastern Sweden, and 0.59 in the whole of Sweden [9].

These differences by region of origin in the world led us to our aim in the present study, i.e., to estimate the incidence of HD in first- and second-generation immigrants in Sweden compared to Swedish-born individuals and Swedish-born individuals with Swedish-born parents, respectively.

Methods

Design

The nationwide registers used in the present study were the Total Population Register and the National Patient Register (NPR). The follow-up period ran from January 1, 1998, until December 31, 2015. A diagnosis of HD from the NPR was registered at the age 18 years and above. Endpoints of the study were thus hospitalization/out-patient care, death, emigration, or the end of the study period on, whichever came first. The NPR includes diagnoses for hospitalized patients, but out-patient diagnoses from specialist care were included from 2001 and onwards. Primary healthcare diagnoses are not included in the NPR. First- and second-generation immigrants were included, divided by region of origin or by region of origin in the parents of the individuals, respectively.

Outcome variable

Morbus Huntington’s disease (HD) (G10).

Demographic and socioeconomic variables

The study population was stratified by sex.

Age was used as a continuous variable in the analysis.

Educational attainment was categorized as ≤9 years (partial or complete compulsory schooling), 10–12 years (partial or complete secondary schooling), and >12 years (attendance at college and/or university).

Marital status was categorized as married or not being married.

Geographic region of residence was included in order to adjust for possible regional differences in hospital admissions and was categorized as (1) large cities, (2) southern Sweden, and (3) northern Sweden. Large cities were defined as municipalities with a population of >200,000 and comprised the three largest cities in Sweden: Stockholm, Gothenburg, and Malmö.

Region of origin of first-generation immigrants, or of the parents to second-generation immigrants, was categorized into (1) Finland; (2) Europe (with the exclusion of Finland) and North America; and (3) Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

Neighborhood deprivation

The neighborhood deprivation index was categorized into four groups: more than one standard deviation (SD) below the mean (low deprivation level or high socioeconomic status (SES)), more than one SD above the mean (high deprivation level or low SES), within one SD of the mean (moderate SES or moderate deprivation level) used as reference group, and also unknown neighborhood SES.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean and standard deviations, and categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages. Cox regression analysis was used for estimating the risk (hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI)) of incident HD in different immigrant groups compared to the Swedish-born population during the follow-up time. All analyses were stratified by sex. Two models were used in our analyses: Model 1 was adjusted for age and region of residence in Sweden, and Model 2 for age, region of residence in Sweden, educational level, marital status, and neighborhood SES.

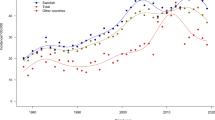

We also analyzed age-specific incidence rates for Swedish-born and foreign-born individuals, respectively, and for men and women. Besides, incidence rates over time were analyzed, age-standardized to the European population.

Results

In the first-generation study (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1a), 6,042,891 individuals were included (2,902,918 men and 3,139,973 women), with 1034 incident cases (478 men and 556 women), giving a mean age-standardized incidence among men of 0.73 and among women of 0.81 per 100,000 person-years (Supplementary Figure S1). The mean age-standardized incidence among Swedish-born was 0.81 per 100,000 person-years and among foreign-born 0.53 per 100,00 person-years (Supplementary Figure S2). The highest incidence rate among Swedish-born was at 55–59 years of age, while among foreign-born, there were three peaks, i.e., in the years 35–39 years, 55–59 years, and 70–74 years of age, with the highest incidence in the oldest age group.

In the second-generation study (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1b), 4,860,469 individuals were included (2,473,605 men and 2,386864 women), with 1001 incident cases (488 men and 513 women). In the first-generation study, there was a similar pattern regarding socioeconomic factors in the population and in HD cases, but among women, less cases had the highest educational level (Supplementary Tables 2a and 2b). In the second-generation study, the pattern was similar in women with foreign-born parents regarding educational level (Supplementary Tables 3a and 3b).

In the first-generation study, among foreign-born men (Table 2), the fully adjusted HR was 0.90 (95% CI 0.68–1.19), and among foreign-born women (Table 2), the fully adjusted HR was 0.49 (95% CI 0.36–0.67), with a significantly lower risk among immigrants from Finland, HR 0.22 (95% CI 0.10–0.49), and Asia/Africa/Latin America, HR 0.44 (95% CI 0.25–0.78).

In the second-generation study (Table 3), among men with foreign-born parents, the fully adjusted HR was 1.00 (95% CI 0.75–1.32), with a significantly higher risk among men with parents from Asia/Africa/Latin America, fully adjusted HR 2.69 (95% CI 1.56–4.66), and among women with foreign-born parents, the fully adjusted HR was 0.63 (95% CI 0.45–0.87), with a significantly lower risk among women with parents from Finland, fully adjusted HR 0.45 (95% CI 0.25–0.83).

Discussion

The main findings of this study were significantly lower risks of HD among both first- and second-generation immigrant women in general. Regarding specific groups, women from Finland, and women with parents from Finland, showed especially lower risks. Additionally, a lower risk was found in first-generation women born outside Europe and North America. Higher risks of HD were seen only among second-generation men with parents from outside Europe and North America.

We choose to categorize immigrants into three groups. The prevalence of HD in Finland has been shown to be lower than in other parts of Europe, with a heritage more similar to Asia [10]. Besides, the Finnish group has traditionally been the largest immigrant group in Sweden and is still one of the largest. Interestingly, we only found a lower HD risk in first- and second-generation women but not in men. However, there are also differences within countries, which could be an explanation to the discrepancy between men and women.

European populations, including European descendants in North America and Australia, have a high prevalence of HD [1, 4, 5], and we found no statistically significant differences compared to Swedish-born individuals or Swedish-born individuals with Swedish-born parents.

Regarding the third group, i.e., individuals from Asia, Africa, or Latin America, or with parents from these regions, there are previous studies showing a lower risk of HD. Asian populations are shown to have a very low prevalence [1, 4, 5] but with a prevalence in the Middle East of 3–4 per 100,000 [11], i.e., somewhat lower than in European or Caucasian populations. Studies from Africa and Latin America are scarce but with a low prevalence [12, 13]. However, there are also differences within countries; in Sweden, a higher prevalence has been found in the north-western region [9]. There seems to be an even higher prevalence in some restricted areas in Latin America [12], in Egypt [14], and also in Tasmania [15]. We found a discrepancy between first- and second-generation individuals, with a lower risk in first-generation women, in line with what could be expected, but a higher risk in men with parents from Asia, Africa, and Latin America. We have no explanation to these findings, but the number of cases was rather small.

An overall explanation to a higher prevalence of HD in Swedish-born individuals could be that there is an awareness in Swedish families about the parents and grandparents with HD, potentially increasing the chance of identifying symptoms. Some immigrant groups may hypothetically not have such awareness.

This study has limitations. The number of cases was quite low, why we had to categorize the individuals into a few groups, i.e., Finland, Europe (except Finland), and North America and Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Besides, differences within countries and regions could be substantial. The strengths lie in the Swedish registers that have been shown to be of high quality [16, 17], and we expect that we have detected most cases in the Swedish National Patient Register.

In conclusion, we found a lower risk of HD in first- and second-generation women overall but also in first- and second-generation women from Finland. The findings in men went in a different direction, at least partially. To some part, this higher incidence could be explained by a higher awareness about HD among blood relatives in individuals with Swedish-born parents than in individuals with foreign-born parents.

References

Novak MJ, Tabrizi SJ (2011) Huntington’s disease: clinical presentation and treatment. Int Rev Neurobiol 98:297–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-381328-2.00013-4

(1993) A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington’s disease chromosomes. The Huntington's Disease Collaborative Research Group. Cell 72(6):971–983. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(93)90585-e

Ross CA, Aylward EH, Wild EJ, Langbehn DR, Long JD, Warner JH, Scahill RI, Leavitt BR, Stout JC, Paulsen JS, Reilmann R, Unschuld PG, Wexler A, Margolis RL, Tabrizi SJ (2014) Huntington disease: natural history, biomarkers and prospects for therapeutics. Nat Rev Neurol 10(4):204–216. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2014.24

Rawlins MD, Wexler NS, Wexler AR, Tabrizi SJ, Douglas I, Evans SJ, Smeeth L (2016) The prevalence of Huntington’s disease. Neuroepidemiology 46(2):144–153. https://doi.org/10.1159/000443738

Pringsheim T, Wiltshire K, Day L, Dykeman J, Steeves T, Jette N (2012) The incidence and prevalence of Huntington’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord 27(9):1083–1091. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.25075

Evans SJ, Douglas I, Rawlins MD, Wexler NS, Tabrizi SJ, Smeeth L (2013) Prevalence of adult Huntington’s disease in the UK based on diagnoses recorded in general practice records. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 84(10):1156–1160. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2012-304636

Fisher ER, Hayden MR (2014) Multisource ascertainment of Huntington disease in Canada: prevalence and population at risk. Mov Disord 29(1):105–114. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.25717

Wexler NS, Collett L, Wexler AR, Rawlins MD, Tabrizi SJ, Douglas I, Smeeth L, Evans SJ (2016) Incidence of adult Huntington's disease in the UK: a UK-based primary care study and a systematic review. BMJ Open 6(2):e009070. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009070

Roos AK, Wiklund L, Laurell K (2017) Discrepancy in prevalence of Huntington’s disease in two Swedish regions. Acta Neurol Scand 136(5):511–515. https://doi.org/10.1111/ane.12762

Sipila JO, Hietala M, Siitonen A, Paivarinta M, Majamaa K (2015) Epidemiology of Huntington’s disease in Finland. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 21(1):46–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.10.025

Scrimgeour EM (2009) Huntington disease (chorea) in the middle East. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J 9(1):16–23

Castilhos RM, Augustin MC, Santos JA, Perandones C, Saraiva-Pereira ML, Jardim LB, Rede N (2016) Genetic aspects of Huntington’s disease in Latin America. A systematic review. Clin Genet 89(3):295–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/cge.12641

Rawlins M (2010) Huntington's disease out of the closet? Lancet 376(9750):1372–1373. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60974-9

Kandil MR, Tohamy SA, Fattah MA, Ahmed HN, Farwiez HM (1994) Prevalence of chorea, dystonia and athetosis in Assiut, Egypt: a clinical and epidemiological study. Neuroepidemiology 13(5):202–210. https://doi.org/10.1159/000110380

Pridmore SA (1990) The prevalence of Huntington’s disease in Tasmania. Med J Aust 153(3):133–134

Ludvigsson JF, Almqvist C, Bonamy AK, Ljung R, Michaelsson K, Neovius M, Stephansson O, Ye W (2016) Registers of the Swedish total population and their use in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 31(2):125–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-016-0117-y

Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, Feychting M, Kim JL, Reuterwall C, Heurgren M, Olausson PO (2011) External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 11:450. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-450

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by Karolinska Institute.

Funding

This work was supported by the ALF funding awarded to Jan Sundquist and Kristina Sundquist and by grants from the Swedish Research Council (awarded to Kristina Sundquist and to Jan Sundquist).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was not applicable, as the study was based on anonymized data from registers. Research data are not shared. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Lund (ref nr 2012/795).

Informed consent

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 292 kb).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wändell, P., Fredrikson, S., Carlsson, A.C. et al. Huntington’s disease among immigrant groups and Swedish-born individuals: a cohort study of all adults 18 years of age and older in Sweden. Neurol Sci 42, 3851–3856 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-021-05085-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-021-05085-6