Abstract

Background

To compare outcomes of a short and long weaning strategy of anti-tumor necrosis factor (aTNF) in our prospective juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) cohort.

Research design and methods

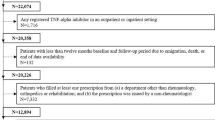

JIA patients on subcutaneous adalimumab with at least 6 months of follow-up were recruited (May 2010–Jan 2022). Once clinical remission on medication (CRM) was achieved, adalimumab was weaned according to two protocols—short (every 4-weekly for 6 months and stopped) and long (extending dosing interval by 2 weeks for three cycles until 12-weekly intervals and thereafter stopped) protocols. Outcomes assessed were flare rates, time to flare, and predictors.

Results

Of 110 JIA patients, 77 (83% male, 78% Chinese; 82% enthesitis-related arthritis) underwent aTNF weaning with 53% on short and 47% on long weaning protocol. The total flare rate during and after stopping aTNF was not different between the two groups. The time to flare after stopping aTNF was not different (p = 0.639). Positive anti-nuclear antibody increased flare risk during weaning in long weaning group (OR 7.0, 95%CI: 1.2–40.8). Positive HLA-B27 (OR 6.5, 95%CI: 1.1–30.4) increased flare risks after stopping aTNF.

Conclusion

Duration of weaning aTNF may not minimize flare rate or delay time to flare after stopping treatment in JIA patients. Recapture rates for inactive disease at 6 months remained high for patients who flared after weaning or discontinuing medication.

Key Points |

• It may not be necessary to taper aTNF over a long period in JIA patients as the duration of spacing out aTNF therapy after achieving CRM may not minimize the flare rate or delay time to flare. • A positive HLA-B27 increased the flare risks after aTNF discontinuation, regardless of the weaning duration. • Recapture rates for CID at 6 months remained high for patients who flared after weaning or discontinuing medication. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical reasons.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Ravelli A, Martini A (2007) Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lancet 369(9563):767–778

Dave M, Rankin J, Pearce M et al (2020) Global prevalence estimates of three chronic musculoskeletal conditions: club foot, juvenile idiopathic arthritis and juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. Pediatr Rheumatol 18(1):1–7

Rebane K, Ristolainen L, Relas H et al (2019) Disability and health-related quality of life are associated with restricted social participation in young adults with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol 48(2):105–113

Chhabra A, Robinson C, Houghton K et al (2020) Long-term outcomes and disease course of children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis in the ReACCh-Out cohort: a two-centre experience. Rheumatology 59(12):3727–3730

Martini A, Lovell DJ, Albani S et al (2022) Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 8(1):5

Teh KL, Tanya M, Das L et al (2021) Outcomes and predictors of juvenile idiopathic arthritis in Southeast Asia: a Singapore longitudinal study over a decade. Clin Rheumatol 40:2339–2349

Zaripova LN, Midgley A, Christmas SE et al (2021) Juvenile idiopathic arthritis: from aetiopathogenesis to therapeutic approaches. Pediatr Rheumatol 19(1):1–14

Shenoi S, Horneff G, Aggarwal A et al (2024) Treatment of non-systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 20:170–181

Onel KB, Horton DB, Lovell DJ et al (2022) 2021 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: therapeutic approaches for oligoarthritis, temporomandibular joint arthritis, and systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 74(4):553–569

Ringold S, Angeles-Han ST, Beukelman T et al (2019) 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation guideline for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: therapeutic approaches for non-systemic polyarthritis, sacroiliitis, and enthesitis. Arthritis Care Res 71(6):717–734

Giannini E, Ilowite N, Lovell D et al (2009) Long-term safety and effectiveness of etanercept in children with selected categories of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 60(9):2794–2804

Hashkes PJ, Uziel Y, Laxer RM (2010) The safety profile of biologic therapies for juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 6(10):561–571

Grazziotin LR, Currie G, Twilt M et al (2021) Evaluation of real-world healthcare resource utilization and associated costs in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a Canadian retrospective cohort study. Rheumatol Ther 8:1303–1322

Livermore P, Eleftheriou D, Wedderburn L (2016) The lived experience of juvenile idiopathic arthritis in young people receiving etanercept. Pediatr Rheumatol 14(1):1–6

Gieling J, van den Bemt B, Hoppenreijs E et al (2022) Discontinuation of biologic DMARDs in non-systemic JIA patients: a scoping review of relapse rates and associated factors. Pediatr Rheumatol 20(1):1–12

Horton DB, Onel KB, Beukelman T et al (2017) Attitudes and approaches for withdrawing drugs for children with clinically inactive nonsystemic JIA: a survey of the childhood arthritis and rheumatology research alliance. J Rheumatol 44(3):352–360

Petty RE, Southwood TR, Manners P et al (2004) International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheumatol 31(2):390–392

Lambert RG, Bakker PA, van der Heijde D et al (2016) Defining active sacroiliitis on MRI for classification of axial spondyloarthritis: update by the ASAS MRI working group. Ann Rheum Dis 75(11):1958–1963

Stoustrup P, Resnick CM, Pedersen TK et al (2019) Standardizing terminology and assessment for orofacial conditions in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: international, multidisciplinary consensus-based recommendations. J Rheumatol 46(5):518–522

Wallace CA, Ruperto N, Giannini E et al (2004) Preliminary criteria for clinical remission for select categories of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol 31(11):2290–2294

Ravelli A, Consolaro A, Horneff G et al (2018) Treating juvenile idiopathic arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis 77(6):819–828

Schett G, Emery P, Tanaka Y et al (2016) Tapering biologic and conventional DMARD therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: current evidence and future directions. Ann Rheum Dis 75(8):1428–1437

Edwards CJ, Fautrel B, Schulze-Koops H et al (2017) Dosing down with biologic therapies: a systematic review and clinicians’ perspective. Rheumatology 56(11):1847–1856

Verhoef LM, van den Bemt BJ, van der Maas A et al (2019) Down-titration and discontinuation strategies of tumour necrosis factor–blocking agents for rheumatoid arthritis in patients with low disease activity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 5:1465–1858

Prince F, Twilt M, Simon S et al (2009) When and how to stop etanercept after successful treatment of patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 68(7):1228–1229

Remesal A, De Inocencio J, Merino R et al (2010) Discontinuation of etanercept after successful treatment in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol 37(9):1970–1971

Pratsidou-Gertsi P, Trachana M, Pardalos G et al (2010) A follow-up study of patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis who discontinued etanercept due to disease remission. Clin Exp Rheumatol 28(6):919–22

Cai Y, Liu X, Zhang W et al (2013) Clinical trial of etanercept tapering in juvenile idiopathic arthritis during remission. Rheumatol Int 33:2277–2282

García-Fernández A, Briones-Figueroa A, Calvo-Sanz L et al (2022) Evaluation of flare rate and reduction strategies for bDMARDs in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: real world data from a single-centre cohort. Rheumatol Int 42(7):1133–1142

Quartier P, Alexeeva E, Constantin T et al (2021) Tapering canakinumab monotherapy in patients with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis in clinical remission: results from a phase IIIb/IV open-label, randomized study. Arthritis Rheumatol 73(2):336–346

Halyabar O, Mehta J, Ringold S et al (2019) Treatment withdrawal following remission in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a systematic review of the literature. Pediatr Drugs 21(6):469–492

Kearsley-Fleet L, Baildam E, Beresford MW et al (2023) Successful stopping of biologic therapy for remission in children and young people with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatology 62(5):1926–1935

Simonini G, Ferrara G, Pontikaki I et al (2018) Flares after withdrawal of biologic therapies in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: clinical and laboratory correlates of remission duration. Arthritis Care Res 70(7):1046–1051

Jiang K, Frank MB, Chen Y et al (2013) Genomic characterization of remission in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 15:1–14

Liao C-H, Chiang B-L, Yang Y-H (2021) Tapering of biological agents in juvenile ERA patients in daily clinical practice. Front Med 8:665170

Teh KL, Das L, Book YX et al (2022) Sacroiliitis at diagnosis as a protective predictor against disease flare after stopping medication: outcomes of a Southeast Asian enthesitis-related arthritis (ERA) longitudinal cohort. Clin Rheumatol 41(10):3027–3034

Gerss J, Tedy M, Klein A et al (2022) Prevention of disease flares by risk-adapted stratification of therapy withdrawal in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results from the PREVENT-JIA trial. Ann Rheum Dis 81(7):990–997

Abel D, Weiss PF (2023) When to stop medication in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 35(5):265–272

Aires PP, Terreri M, Silva VB et al (2021) Duration of inactive disease while off disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs seems to influence flare rates in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: an observational retrospective study. Acta Reumatologica Port 46(2):120–125

Baszis K, Garbutt J, Toib D et al (2011Oct) Clinical outcomes after withdrawal of anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a twelve-year experience. Arthritis Rheum 63(10):3163–3168

Ringold S, Dennos AC, Kimura Y et al (2023) Disease recapture rates after medication discontinuation and flare in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: an observational study within the childhood arthritis and rheumatology research alliance registry. Arthritis Care Res 75(4):715–723

Emery P, Burmester GR, Naredo E et al (2020) Adalimumab dose tapering in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who are in long-standing clinical remission: results of the phase IV PREDICTRA study. Ann Rheum Dis 79(8):1023–1030

van Esveld L, Cox JM, Kuijper TM et al (2023) Cost–utility analysis of tapering strategies of biologicals in rheumatoid arthritis patients in the Netherlands. Ann Rheum Dis 82(10):1296–1306

Vande Casteele N, Abreu MT, Flier S et al (2022) Patients with low drug levels or antibodies to a prior anti-tumor necrosis factor are more likely to develop antibodies to a subsequent anti-tumor necrosis factor. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol: Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc 20(2):465-467 e2

Mok CC, van der Kleij D, Wolbink GJ (2013) Drug levels, anti-drug antibodies, and clinical efficacy of the anti-TNFα biologics in rheumatic diseases. Clin Rheumatol 32(10):1429–1435

Acknowledgements

We thank our JIA children and families for participating in the inception cohort and registry. Their physical and mental support to the rheumatology team and JIA families in need of help throughout the past decade is much appreciated.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. KLT, YXB, and TA performed data collection and interpretation. TA did the data analysis. KLT and TA wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and the authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The SingHealth Centralised Institutional Review Board (CIRB) approved this study and waived the need for informed consent for this database study (CIRB 2019/2961).

Disclosures

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

An abstract of this manuscript was previously presented at the EULAR Congress in Copenhagen, in June 2022, as a poster tour presentation (POS0342).

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Teh, K.L., Das, L., Book, Y.X. et al. Anti-tumor necrosis factor (aTNF) weaning strategy in juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA): does duration matter?. Clin Rheumatol 43, 1723–1733 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-024-06928-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-024-06928-1