Abstract

Gout is one of the most common noncommunicable diseases in Hong Kong. Although effective treatment options are readily available, the management of gout in Hong Kong remains suboptimal. Like other countries, the treatment goal in Hong Kong usually focuses on relieving symptoms of gout but not treating the serum urate level to target. As a result, patients with gout continue to suffer from the debilitating arthritis, as well as the renal, metabolic, and cardiovascular complications associated with gout. The Hong Kong Society of Rheumatology spearheaded the development of these consensus recommendations through a Delphi exercise that involved rheumatologists, primary care physicians, and other specialists in Hong Kong. Recommendations on acute gout management, gout prophylaxis, treatment of hyperuricemia and its precautions, co-administration of non-gout medications with urate-lowering therapy, and lifestyle advice have been included. This paper serves as a reference guide to all healthcare providers who see patients who are at risk and are known to have this chronic but treatable condition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The global incidence and prevalence of gout has substantially increased over the past decade [1], and this is no exception in Hong Kong. A local population-based study reported an increase in the crude incidence rate of gout from 113.05/100,000 person-years in 2006 to 211.62/100,000 person-years in 2016 [2]. Similarly, the crude prevalence of gout has risen from 1.56% in 2006 to 2.92% in 2016 [2]. Population aging has contributed significantly to the increased incidence and prevalence of gout in Hong Kong. Over the past 20 years, the number of Hong Kong people aged 65 years or above increased from 12.5% to 16.1%. In addition, modifiable risk factors for gout and hyperuricemia, such as regular alcohol consumption, greater meat intake, and obesity, have been increasing. As a result, the Hong Kong government has included gout, alcohol drinking, and obesity among the target non-communicable diseases in its campaign programs for primary prevention [3]. However, the management of gout in Hong Kong is yet to be improved.

The treatment goal usually focuses on relieving symptoms of arthritis but not treating the underlying hyperuricemia. Despite the availability and demonstrated efficacy of urate-lowering therapy (ULT) in reducing serum uric acid (SUA) levels, only 25.55% of all gout patients received ULT and only 35.8% of these patients achieved the target SUA level of < 0.36 mmol/L (6 mg/dL). Almost all gout patients received allopurinol because it is subsidized by the government. Other unsubsidized ULT options, including febuxostat, were prescribed to < 1% of all gout patients [2]. Resolving the unmet need for the management of hyperuricemia and gout is challenging, because this includes certain patient factors, such as pharmacologic compliance, adverse reactions, and lack of health literacy, and healthcare provider factors, such as under-recognition of over-producers and/or under-excretors, as well as knowledge gaps in gout management [4, 5].

Although several international guidelines for the management of gout are available, there are certain differences according to their ethnic, genetic, social, and cultural background, clinical practice, and the availability of medicine [6,7,8,9,10]. The Hong Kong Society of Rheumatology (HKSR), a professional organization that has been at the helm of training and improving the care of patients with rheumatic diseases in Hong Kong, spearheaded the development of these consensus recommendations aiming at improving the acute and long-term management of gout, particularly focusing on aspects related to the clinical practice in Hong Kong. It is hoped that these recommendations can offer guidance to not only primary care practitioners, but also specialists who regularly see patients who are at risk for gout and its complications.

Method

Steering committee

Eight core members of the Gout Special Interest Group (Gout SIG) from the HKSR met through several rounds of teleconferences from July 2020 onwards to discuss proposed consensus recommendations relevant to the management of gout in Hong Kong. Priority areas covered during the meetings included: (1) acute gout management, (2) gout prophylaxis, (3) treatment of hyperuricemia, (4) co-administration of non-gout medications with ULT, and (5) lifestyle modifications aimed at reducing SUA. A total of four overarching principles and 24 major recommendations were reviewed and tweaked. A systematic literature search was concurrently performed to identify and grade the relevant level of evidence for each recommendation.

Literature search and grading of evidence

Evidence for the consensus statements was identified through an online search of the Medline database with the search terms “acute gout therapy,” “clinical practice guidelines,” “gout,” “gout prophylaxis,” “hyperuricemia,” “lifestyle modification,” “precaution,” “urate lowering therapy,” and “non-pharmacological management” and other relevant key words in the statements. Studies included were published in the past 10 years including systematic reviews, meta-analyses, clinical trials, cohort studies, and clinical practice guidelines published in English. The level of evidence of each statement was evaluated based on the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine system (Table 1) [11].

Consensus formation

Practicing rheumatologists registered as full members of the HKSR and a selected group of family physicians, renal physicians, and internists with special interest and extensive clinical experience in gout management were invited to participate in a modified Delphi exercise. Each overarching statement and all major statements were sent to the participants for voting through anonymized online surveys. The eight core members of the steering committee were excluded from the voting sessions to avoid bias and skewing of the results. The participants were provided with the results of the literature search, explanatory notes, and the level of evidence grading. For each statement, the members were asked to share their level of agreement (strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, and strongly disagree) using an online platform hosted by MIMS, an independent medical communications company. They were also invited to give feedback on the statements, indicate reasons for disagreement, and suggest edits or improvements. Consensus was defined as an agreement (strongly agree or agree) of ≥ 80% by the Delphi participants. The anonymized voting results and feedback were then communicated to the core members. Statements that did not meet consensus were then either removed or modified and redeployed to the Delphi participants along with brief elucidatory notes for the subsequent rounds of voting until consensus was reached.

Results

A total of 84 full HKSR members and 11 practitioners from various specialties were invited. Overall, 60 participated in the Delphi process. The group consisted of 83% rheumatologists, 9% renal medicine specialists, 5% general practitioners, and 3% internists. Among the HKSR members, the response rate was 60% (50 of 84 eligible practicing rheumatologists). After two rounds of voting, consensus was reached for all overarching statements and for 20 of the 24 major statements. The results of the voting for rounds 1 and 2 are summarized in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Overarching principles

These unifying themes include general recommendations on lifestyle and educational interventions, and the adequate management of comorbidities. These endeavors are typically included in health literacy campaigns to prevent and control the symptoms and complications of gout [3].

-

A.

“Where possible, every patient with gout should be educated about the pathophysiology of the disease, treatment options for gouty arthritis, its associated comorbidities, and indications of urate-lowering agents.”

Most studies cite suboptimal understanding of gout and its treatment as a common barrier to gout care. Physicians should effectively communicate to their patients the direct causal role of hyperuricemia to gout and gouty arthritis and its comorbidities, as well as the treatable nature of the disease [12].

-

B.

“Every patient with gout should receive advice from their healthcare professionals regarding lifestyle modification and its role in the management of gout.”

Although gout is considered as a chronic and potentially progressive condition requiring long-term management, many people with gout falsely regard gout as an episodic illness and are thus prone to poor medication compliance and lack of treatment response or paradoxical attacks [12]. It is thus crucial to discuss the treatment plan with patients to lessen the risk of gout attacks and the metabolic complications associated with hyperuricemia [3].

-

III.

“Apart from rheumatologists, non-rheumatologist physicians and/or general practitioners should be responsible for managing patients with gout. However, rheumatologists should provide specialist care for patients with gouty arthritis refractory to treatment with first-line therapies or those who fail to achieve the treatment target despite appropriate use of ULT.”

The continued partnership between patients and primary care and other health professionals plays an important role in monitoring and improving the management of gout in Hong Kong [3]. Rheumatologists are often called in to reinforce the management of gout patients; they determine whether gout is the cause of arthritis and provide specialist advice to further enhance education on adherence and continued monitoring of the signs and symptoms of gout.

-

IV.

“Every patient with gout should be systematically screened for associated comorbidities and cardiovascular risk factors.”

A systematic review by van Durme et al. revealed that hyperuricemia appears to be a risk indicator and is a component of the metabolic syndrome, rather than an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease, but may nonetheless contribute to a slight increase in cardiovascular risk. Renal disease, on the other hand, appears to be markedly prevalent among hyperuricemic patients and may therefore need to be considered when administering ULT to at-risk patients [13].

Acute gout management

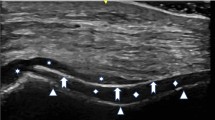

First-line options include colchicine, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), or glucocorticoids (e.g., oral, intra-articular, or intramuscular). The choice of treatment is often dependent on the patient’s comorbidities and overall disease severity [8, 10, 13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Initial combination therapy may be needed for patients experiencing severe pain or attacks affecting multiple joints (Fig. 1) [21], although the combination of an NSAID with systemic glucocorticoid is not recommended because of their additive toxicity.

Consensus recommendations on the management of acute gout attack [6]. COX, cyclooxygenase; IL, interleukin; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; ULT, urate-lowering therapy

Statement 1

“Acute flares of gout should be treated as early as possible, preferably within 12 h. Patients should be educated to self-medicate at the first warning symptoms.”

Level of evidence: 1B

Early management of flares (i.e., by self-initiated medication) is widely recommended by treatment guidelines based on high-grade evidence [8, 10, 14,15,16,17]. Anti-inflammatory therapy offers relief from pain and resolution of joint inflammation when administered within 12 h of an attack. In particular, low-dose colchicine self-administered within 12 h of flare onset has been shown to significantly reduce baseline pain without the associated gastrointestinal side effects associated with high-dose regimens [22]. Prompt treatment might also ameliorate the risk for cardiovascular events recently found to be associated with gout flares [23].

Statement 2

“Colchicine, NSAIDs, or glucocorticoids (oral, intra-articular, or intramuscular) are recommended as first-line therapy for gout flares.”

Level of evidence: 1B

Colchicine can be given at a loading dose of 1 mg, followed by 0.5 mg 1 h later on day 1; subsequent doses can be given at 0.5 mg twice or three-times daily until symptoms subside, or intolerable side effects occur. A gout flare generally warrants a higher dose of NSAID. However, treatment should be continued for the shortest possible duration needed to fully control the attack (typically 3–5 days) and to prevent recurrence. One potential advantage of NSAIDs is their analgesic effect, which may reduce pain before inflammation subsides. The typical glucocorticoid regimen is oral prednisolone 30 mg/day or 0.5 mg/kg for 5 days or tapered over 7–14 days. Joint aspiration and injection of intra-articular glucocorticoids are particularly indicated in flares affecting large joints or where there are other differential diagnoses [8, 10, 14,15,16,17,18,19,20, 24, 25].

Statement 3

“The choice of drug(s) should be based on the presence of comorbidities, patient's previous response to treatments, the severity of flares, and the number and type of joint(s) involved.”

Level of evidence: 1B

Colchicine dose should be reduced in patients with renal impairment and avoided in patients with severe renal impairment (glomerular filtration rate [GFR] < 30 mL/min) or in those receiving strong P-glycoprotein and/or cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 inhibitors such as cyclosporin or clarithromycin. The concomitant use of statins may also increase the risk of myopathy and rhabdomyolysis. Evidence does not support the preferred use of any one NSAID, including cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, over another, so selection should be based on the patient’s prior response and concern over specific side effects. NSAIDs should be avoided in patients with renal impairment. Finally, systemic glucocorticoids are useful in acute, severe, and/or polyarticular attacks. A single dose of intramuscular glucocorticoids can be given, especially when a more rapid effect is desired. Intra-articular glucocorticoid injections are useful in patients with severe attacks involving one or two joints, especially in large weight-bearing joints [8, 10, 14,15,16,17,18,19,20, 24, 25].

Statement 4

“Use topical ice as an adjuvant therapy for pain relief.”

Level of evidence: 1B

In a small, randomized study of 19 patients with acute gout, the group treated with ice reported greater reduction in pain compared with patients in the control group. Both groups were also given prednisolone and colchicine [26].

Statement 5

“Interleukin-1 (IL-1) inhibitors can be considered for treatment of gout flare in patients who have inadequate response to or are contraindicated for standard treatment (including colchicine, NSAIDs, and/or glucocorticoids). IL-1 inhibitors are contraindicated in patients with active infection.”

Level of evidence: 1B

IL-1 inhibitors may be used in refractory polyarticular or tophaceous gout or for patients who are unable to tolerate conventional therapy for acute flares. These agents have been evaluated in case series and small randomized controlled trials/based on a low to moderate level of evidence. These agents may be an option in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), but its associated potential infectious complications and cost/benefit ratio must be carefully considered. Anakinra, an IL-1 receptor antagonist that inhibits the activity of both IL-1α and IL-1β, is effective in reducing acute gout pain and inflammation and may be a reasonable option in patients with CKD [27,28,29,30,31,32]. Rilonacept, a soluble decoy receptor that binds to IL-1β, may be used to reduce the risk of recurrent attacks [33]. Canakinumab may be an effective option in reducing both pain in acute attacks and the risk of recurrent attacks [34,35,36].

Gout prophylaxis

Moderate quality evidence supports the administration of agents for flare prophylaxis, mainly with colchicine, among patients being treated with ULT during the first 6 months [8, 37,38,39,40,41].

Statement 6

“Prophylaxis with colchicine 0.5 mg once or twice daily for 3–6 months is recommended during initiation or up-titration of ULT.”

Level of evidence: 2B

Colchicine should be used with caution in patients with renal or hepatic impairment. In patients receiving medications that inhibit CYP3A4 and/or the P-glycoprotein efflux pump, dosage adjustment or avoidance of colchicine is warranted [42].

Statement 7

“In patients who cannot tolerate colchicine, a low-dose NSAID can be considered as an alternative for prophylaxis after weighing the risks and benefits.”

Level of evidence: 2B

Alternate regimens, such as low-dose NSAIDs, may be of benefit in patients who may present with relative or absolute contraindications to colchicine therapy. However, the routine use of low-dose NSAIDs, glucocorticoids, as well as IL-1 inhibitors for gout prophylaxis is not currently supported by strong evidence [8, 43,44,45,46]; therefore, careful consideration of the risks and benefits (i.e., not only evaluation of contraindications) may be clinically relevant in certain populations.

Indications for urate-lowering therapy

Clinical trials have demonstrated that ULT is effective in treating patients with recurrent flares, tophi, urate arthropathy, and/or renal stones [47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69].

Statement 8

“ULT should be discussed with all patients diagnosed with gout.”

Level of evidence: 5

As suboptimal understanding of gout and its treatment poses as a common barrier to gout care, the core group considered early introduction of ULT to patients would serve as an important education strategy in the management of gout.

Statement 9

“ULT should not be routinely recommended on the first attack of gout in patients without comorbidities.”

Level of evidence: 5

The usefulness of ULT in patients diagnosed with gout is most apparent in patients with recurrent gouty arthritis and with associated signs and symptoms of either tophaceous or non-tophaceous arthropathy [69, 70]. It is not particularly advised for patients who experience a single, isolated episode of pain or joint swelling to receive ULT. A study by Yu and Gutman documented that only 62% of patients with gout had a second attack within a year [71]. A Canadian study showed that gout treatment only becomes cost-effective in patients who experience at least three attacks per year [70]. Therefore, ULT should be reserved for patients who have documented organ affectation or in those who experience frequent flares. On the other hand, there is also fear of delaying the initiation of ULT until the second or third attack, exposing patients to a higher crystal load, which may be deleterious for the cardiovascular system and kidneys [8, 10]. Therefore, the panel considers that in selected patients who prefer to start treatment after thorough discussions on the risks and benefits, ULT might remain an option.

Statement 10

“ULT should be recommended to all gout patients with tophi, radiographic damage related to gout, OR recurrent attacks (≥ 2 times per year).”

Level of evidence: 1B

High-quality evidence from a randomized controlled trial and as confirmed by a meta-analysis demonstrated that ULT can reduce tophi size and numbers [48, 54]. Various authorities set a range of 0–3 attacks a year, but most guidelines have adopted a strategy of initiating ULT after two attacks per year [8, 10, 14,15,16,17].

Statement 11

“ULT can be considered in patients with gout after the first attack with urolithiasis, more than one flare but with infrequent attacks per year, or in those with renal impairment.”

Level of evidence: 1B

In patients with a history of urolithiasis or those experiencing calcium oxalate renal stones and/or hyperuricosuria, ULT has been documented to provide benefit by lowering 24-h urinary uric acid excretion more significantly than placebo [55, 56]. The 3-year incidence of stone-related events was shown to decrease in those treated with allopurinol vs. those treated with placebo [57]. However, the benefit of ULT appears to decrease in patients with less frequent flares compared with when ULT is prescribed to patients with more frequent flares. Dalbeth et al. demonstrated that patients with at the most two previous flares and no more than one attack in the preceding year were less likely to experience a subsequent flare (30% with febuxostat vs. 41% with placebo; p < 0.05) [58]. Hence, the number of gouty attacks should be carefully considered before the decision to start ULT is reached. In addition, renal disease should likewise influence the decision to start ULT. Both allopurinol and febuxostat has been documented to lower 24-h urinary uric acid excretion [56]. Allopurinol is also known to slow the progression of CKD in hyperuricemia patients. Because there is a higher likelihood of gout progression and tophi development in patients with CKD compared with those with no renal impairment, this population may benefit from early initiation of ULT [59,60,61,62,63,64].

Statement 12

“ULT may be considered in patients with gout after the first attack with very high serum urate level (> 0.54 mmol/L [9 mg/dL]) or young onset age (age < 40 years).”

Level of evidence: 1B

The risk of gout rises sharply when serum urate levels are above 0.5 mmol/L (8.4 mg/dL). Patients with markedly elevated serum urate levels > 0.54 mmol/L (9 mg/dL) are more likely to experience gout progression than those with lower levels [66, 67, 69, 72]. Young age is a marker of severity and may be associated with an inborn error of metabolism or dysfunctional variant in the urate transporter [73,74,75,76].

Treatment target of urate-lowering therapy

There is sparse evidence from randomized trials that establishes the treat-to-target approach in gout. However, data from observational studies, including longer extension studies, appear to suggest that SUA < 0.36 mmol/L (6 mg/dL) was associated with reduced gout flares [69, 77,78,79,80,81].

Statement 13

“For patients on ULT, serum urate level should be monitored and maintained below 0.36 mmol/L (6 mg/dL). A target SUA of <0.30 mmol/L (5 mg/dL) is recommended for patients with tophaceous gout.”

Level of evidence: 3

The aim of ULT is to reduce and maintain the serum urate level to prevent further urate crystal formation, to dissolve existing crystals, and to prevent recurrent flares. The lower the serum urate level, the greater the velocity of crystal elimination [69, 77,78,79,80,81,82].

Statement 14

“When the clinical tophi have resolved, the serum urate level may be maintained between 0.30 mmol/L (5 mg/dL) and 0.36 mmol/L (6 mg/dL).”

Level of evidence: 3

The recommendation of a less stringent targeted serum urate level of between 0.30 mmol/L (5 mg/dL) and 0.36 mmol/L (6 mg/dL) after clinical tophi have resolved is based on the possibility of adverse effects that may be associated with a very low SUA level [69, 77,78,79,80,81,82]. Studies have shown that hyperuricemia might protect against various neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s disease and dementia, among others, and should therefore be a strong consideration among elderly patients with gout [83, 84].

Precautions in prescribing allopurinol

The human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B*5801 haplotype is the strongest risk factor for allopurinol-induced severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCARs). Allopurinol-induced SCARs include drug hypersensitivity syndrome, Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS), and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Patients who experience SCARs after ULT often have a poor prognosis. However, there are insufficient data to establish firm recommendations for cost-effective screening in populations with low allele frequency [17, 85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98].

Statement 15

“Allopurinol should be avoided in patients who have tested positive for HLA-B*5801 allele.”

Level of evidence: 2B

As mentioned, HLA-B*5801 haplotype is the strongest risk factor for allopurinol-induced SCARs. Screening for HLA-B*5801 is beneficial in populations with high rates of allopurinol-induced toxic epidermal necrolysis/SJS, especially in populations with a higher frequency of the allele (≥ 5%) [92].

Statement 16

“Screening for the HLA-B*5801 allele should be considered for some patients of Asian descent (e.g., Han Chinese, Korean, Thai) and for African American patients, and patients with risk factors to develop allopurinol-induced SCAR, before starting of allopurinol. Risk factors included patients who are ≥60 years old or with renal insufficiency (CKD stage ≥3).”

Level of evidence: 2B

Certain populations particularly benefit from genetic testing for HLA-B*5801 before allopurinol administration because of the high potential cost-effectiveness of this intervention. In a local study, Wong et al. suggested that pre- treatment HLA-B*5801 screening is cost-effective in Chinese patients with CKD to prevent allopurinol-induced SCARs [99]. Apart from consideration of ethical, legal, and social implications to land at informed policy decision-making, awareness of risk factors, such as age or renal insufficiency, may be necessary to justify the appropriateness of the utilization of this test [92,93,94, 96]. Stamp et al. posit that a starting dose of 1.5 mg per unit of estimated GFR may reduce this risk [98]. The group suggests the use of alternative ULTs (e.g., febuxostat) in these patients.

Use of urate-lowering therapy

The use of ULT for the prevention of recurrent gout flares and disease progression and the treatment of tophi is supported by clinical trials/high level of evidence. The choice between xanthine oxidase inhibitors (XOIs) and/or uricosurics is dependent on a patient’s clinical picture. These recommendations are based on a moderate to high level of evidence [100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115].

Statement 17

“A xanthine oxidase inhibitor (allopurinol or febuxostat) is the preferred agent for all patients with gout.”

Level of evidence: 1A

Allopurinol should be considered as the first-line agent especially in patients with pre-existing major cardiovascular diseases. The starting and maximum dosage of allopurinol should be adjusted according to creatinine clearance in patients with renal impairment [100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115]. However, in individuals who are observed to tolerate allopurinol, there is evidence that gradually increasing the dose above doses based on kidney function is safe and effective in those with chronic kidney disease [116, 117]. There is no evidence that limiting the maintenance dose reduces the risk of allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome [118].

Statement 18

“If the targeted serum urate level cannot be achieved by allopurinol, febuxostat should be considered. Alternatively, combination therapy with a uricosuric agent can be considered in patients without severe renal impairment (GFR <30 mL/min).”

Level of evidence: 1A

Observational and cohort studies have shown that the use of febuxostat in patients with CKD stages 3–5 was not associated with increased adverse events but conferred more significant reduction in serum urate levels vs. allopurinol [100, 103]. Results of the Cardiovascular Safety of Febuxostat and Allopurinol in Participants With Gout and Cardiovascular Comorbidities (CARES) trial, highlight the noninferiority of febuxostat vs. allopurinol as regards rates of adverse cardiovascular events [119]. Although this study posits that all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality were higher with febuxostat than with allopurinol, the long-term Febuxostat versus Allopurinol Streamlined Trial (FAST) study established that after a median follow-up of about 4 years, febuxostat was not associated with a higher risk of death or serious adverse events compared with allopurinol [120]. Hence, the presence of pre-existing major cardiovascular diseases should not preclude the use of febuxostat in patients who fail to achieve the treatment target with allopurinol [101,102,103, 121].

The use of uricosuric monotherapy is not preferred unless patients present with a contraindication or intolerance to both XOIs. The use of allopurinol or febuxostat with a uricosuric agent decreases the urate concentration in urine and thus the risk of urolithiasis [109,110,111,112,113,114,115].

Lifestyle modification

Dietary interventions limiting red meat, seafood, sugary beverages, and alcohol have been the cornerstone of lifestyle management among patients who have gout. Also, moderate to heavy physical activity and overall fitness have been found to be associated with a lower incidence of gout and hyperuricemia [122,123,124,125].

Statement 19

“Patients should be advised to avoid alcohol, fructose, or sugar-sweetened beverages, and decrease dietary protein source from meat and seafood.”

Level of evidence: 2B

A diet that restricts alcohol and purine-rich and fructose-rich foods, while maintaining the intake of low-fat dairy products, healthy protein sources, and vegetables, has been observed to lower the risk of incident gout [122]. Ethanol has been found to facilitate increased urate production through acetate metabolism and enhanced adenosine triphosphate turnover [126,127,128]. Moreover, beer contains purines that have been found to intensify the plasma concentration of uric acid [129, 130]. Substantial intake of red meat and seafood, or food stuffs with high purine content, has been likewise positively correlated with the development of hyperuricemia and gout flares [131]. In a study of vigorously active men, those with higher alcohol intake (per 10 g/day) had a higher relative risk (RR) of 1.19 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.12–1.26; p < 0.0001) and those with a higher meat consumption (per servings/day) had a higher RR (1.45; 95% CI: 1.06–1.92; p = 0.002), whereas those with greater fruit intake (per piece/day) had a lower RR (0.73; 95% CI: 0.62–0.84; p < 0.0001). Men who consumed more than 15 g of alcohol (in particular beer) per day had a 93% higher risk and higher rates of SUA levels than those who had abstained, and men who averaged more than two pieces of fruit/day had cut their risk in half compared with those who ate < 0.5 pieces of fruit/day and had comparative body mass index (BMI) levels (RR: 1.19; 95% CI: 1.15–1.23; p < 0.0001) [123, 132, 133]. Fructose metabolism leads to an increase in purines, which are converted into uric acid. Also, long-term fructose administration suppresses urinary excretion of uric acid leading to hyperuricemia [134]. The consumption of five to six servings of sugar-sweetened soft drinks was associated with an increased multivariate RR of 1.29 (95% CI: 1.00–1.68) compared with one serving a month [135].

Statement 20

“Weight reduction is recommended if BMI > 25 kg/m2.”

Level of evidence: 2B

A prospective cohort study of over 40,000 men with excess adiposity and other key modifiable factors suggests that weight control has the potential to prevent most incident gout cases among men. The authors of the study state that men with obesity may not respond to gout therapy unless weight loss is achieved [122]. In a separate study, the risk of gout was noted to be 16-fold greater for men with BMI > 27.5 kg/m2 than in those who had a BMI < 20 kg/m2. In addition, compared with those who were least active or fit, men who ran ≥ 8 km/day or > 4.0 m/s had 50% and 65% lower risk of gout, respectively [136]. A systematic review by Nielsen et al. showed that low to moderate grade evidence supports weight loss in overweight gout patients achieve SUA targets and have fewer gout attacks at medium-term or long-term follow-up on SUA [137]. Overall, obesity has an impact on both incidence and control of gout.

Discussion

This set of HKSR consensus recommendations for gout management encompasses lifestyle and medical interventions that offer guiding provisions for primary care and specialist clinicians to aid in lowering the risk of gout and hyperuricemia in their patients. The 60 members of the voting faculty represented practicing rheumatologists, renal medicine specialists, general practitioners, and internists in the locality. To date, this paper is the first consensus document on gout management involving most practicing rheumatologists in Hong Kong. The voting panel included over 80% of local practicing rheumatologists. The final recommendation statements consider existing evidence and local viewpoints to aid in the optimization of gout and hyperuricemia control in Hong Kong. The individual recommendations have been enumerated in logical sequence and are intended to guide practitioners in administering appropriate medical treatment coupled with non-pharmacologic interventions, involving several aspects of care that are of particular concern in the locality. For instance, screening for HLA*B-5801 was emphasized and may be justified as standard practice in our clinical setting. In addition, the introduction of newer agents in our locality, such as IL-1 inhibitors for acute gouty attacks in complicated cases and the use of ULT for chronic cases, was included. In most cases, gout and hyperuricemia can be managed in the primary care setting. Patients who are refractory to standard care may require specialist management and should be referred as and when necessary.

Treatment of acute gout remains largely dependent on the severity and the clinical profile of patients. Prompt therapy of acute attacks with colchicine, NSAIDs, or glucocorticoids is considered, but with careful watch over comorbidities, especially renal disease. Although evidence supports the use of IL-1 inhibitors for gout prophylaxis [43,44,45,46], the use of canakinumab and rilonacept may be precluded by their costs and putative infection risks. The group has considered these factors and emphasizes that the availability of these agents should be taken into consideration when administered as first-line prophylaxis for gout. Prophylaxis is currently limited to colchicine and low-dose NSAIDs given to patients during initiation or up-titration of ULT. ULT is effective in treating patients with recurrent flares, tophi, urate arthropathy, and/or renal stones, but not in all instances. A review of the patient’s age, risk factors, current treatments, organ affectations, signs and symptoms, and required treatment targets should be conducted at the onset. Allopurinol remains a popular choice for ULT across various populations. HLA-B*5801 screening should be considered in high-risk patients before initiation of allopurinol. The cost-effectiveness of HLA-B*5801 screening for preventive management of SCARs should be evaluated before the determination of the necessity for this intervention in low-risk patients across the different centers and hospitals in Hong Kong. Febuxostat may be considered as second-choice therapy in those with known allopurinol-induced hypersensitivity or adverse reactions. Recent guidelines recommend switching from febuxostat to other ULT options in patients with a history of cardiovascular disease or new cardiovascular events based on the results of the CARES trial [10, 119]. However, the results of this study pose uncertainties, and data from subsequent exploratory analyses of the CARES trial countered the contended association between febuxostat use and an increased mortality risk [138, 139]. More recent studies have also established the safety of febuxostat after 4 years of use [120, 121]. Hence, the core members of the steering committee suggest that the presence of pre-existing major cardiovascular diseases should not preclude the use of febuxostat in indicated patients.

The panel did not achieve consensus on recommendations pertaining to co-administration of non-gout medications with ULT after two rounds of voting. This may be related to the relative lack of strong evidence [140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147]. However, as reported by an epidemiologic study, the RRs of associated incident gout were lower with current use of calcium channel blockers and losartan. Hence, in gout patients, calcium channel blockers and losartan are preferred over other antihypertensive drugs, e.g., loop or thiazide diuretics, beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and non-losartan angiotensin II receptor blockers [140]. For patients with gout who are receiving low-dose aspirin (< 300 mg daily) alone or in combination with clopidogrel or ticagrelor for prevention or treatment of cardiovascular disease, it is advisable to monitor serum uric acid levels regularly, and make appropriate ULT adjustment accordingly [141, 142]. The long-term efficacy and safety of slow oral desensitization to allopurinol are established for gout patients with maculopapular eruptions who cannot be treated with uricosurics or another ULT; however, it is not recommended in patients with severe hypersensitivity to allopurinol. The panel recognizes that desensitization protocols are not commonly used, with most currently practicing rheumatologists having limited experience in these protocols [97].

Finally, lifestyle modification is a cornerstone in the management of hyperuricemia and gout, and relevant patient education regarding diet and exercise should be espoused when treating these patients.

Local registry studies and trials looking at various aspects of gout therapy may be worthwhile to consider. Other areas of gout treatment, such as the usefulness of surgery and other clinical aspects of care, should be investigated in future studies. These new data may be useful in reshaping upcoming recommendations to support the improvement of gout care in Hong Kong. Likewise, optimization of treatment approaches and holistic management of other metabolic conditions may help in the overall improvement of patients and should become the focus of future guidelines.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available with from the corresponding author with permission of the Hong Kong Society of Rheumatology.

References

Roddy E, Zhang W, Doherty M (2007) The changing epidemiology of gout. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol 3:443–449. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncprheum0556

Tsoi MF, Chung MH, Cheung BMY et al (2020) Epidemiology of gout in Hong Kong: a population-based study from 2006 to 2016. Arthritis Res Ther 22:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-020-02299-5

Hong Kong Centre for Health Protection (2019) Non-communicable diseases watch gout: no longer the disease of kings. https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/ncd_watch_april_2019.pdf. Accessed 24 Jul 2022

Kung K, Lam A, Li P (2004) Review of the management of gout in a primary care clinic. Hong Kong Pract 26:301

The Lancet Rheumatology (2019) Big little lies: challenging misperceptions of gout. Lancet Rheumatol 1:e75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2665-9913(19)30036-0

Khanna D, Khanna PP, Fitzgerald JD et al (2012) 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 2: therapy and antiinflammatory prophylaxis of acute gouty arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 64:1447–1461. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21773

Hui M, Carr A, Cameron S et al (2017) The British Society for Rheumatology guideline for the management of gout. Rheumatology 56:1056–1059. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kex156

Richette P, Doherty M, Pascual E et al (2017) 2016 updated EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of gout. Ann Rheum Dis 76:29–42. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209707

Khanna D, FitzGerald JD, Khanna PP et al (2012) 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part I: systematic non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 64:1431–1446

FitzGerald JD, Dalbeth N, Mikuls T et al (2020) 2020 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the management of gout. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 72:744–760. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.24180

The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine – Levels of evidence (March 2009). https://www.cebm.net/2009/06/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009/. Accessed 24 Jul 2022.

Rai SK, Choi HK, Choi SHJ et al (2018) Key barriers to gout care: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Rheumatology (Oxford). https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kex530

van Durme C, van Echteld IAAM, Falzon L et al (2014) Cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities in patients with hyperuricemia and/or gout: a systematic review of the literature. J Rheumatol Suppl 92:9–14. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.140457

Pillinger MH, Mandell BF (2020) Therapeutic approaches in the treatment of gout. Semin Arthritis Rheum 50:S24–S30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.04.010

Mirmiran R, Bush T, Cerra MM et al (2018) Joint clinical consensus statement of the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons® and the American Association of Nurse Practitioners®: etiology, diagnosis, and treatment consensus for gouty arthritis of the foot and ankle. J Foot Ankle Surg 57:1207–1217. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jfas.2018.08.018

Sidari A, Hill E (2018) Diagnosis and treatment of gout and pseudogout for everyday practice. Prim Care 45:213–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pop.2018.02.004

Yu K-H, Chen D-Y, Chen J-H et al (2018) Management of gout and hyperuricemia: multidisciplinary consensus in Taiwan. Int J Rheum Dis 21:772–787. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185X.13266

Simon Taylor R (2017) BET 1: prednisolone for the treatment of acute gouty arthritis. Emerg Med J 34:687–689. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2017-207129.1

Wilson L, Saseen JJ (2016) Gouty arthritis: a review of acute management and prevention. Pharmacotherapy 36:906–922. https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.1788

Zhang S, Zhang Y, Liu P et al (2016) Efficacy and safety of etoricoxib compared with NSAIDs in acute gout: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol 35:151–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-015-2991-1

Coburn BW, Mikuls TR (2016) Treatment options for acute gout. Fed Pract 33:35–40

Terkeltaub RA, Furst DE, Bennett K et al (2010) High versus low dosing of oral colchicine for early acute gout flare: twenty-four-hour outcome of the first multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, dose-comparison colchicine study. Arthritis Rheum 62:1060–1068. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.27327

Cipolletta E, Tata LJ, Nakafero G et al (2022) Association between gout fare and subsequent cardiovascular events among patients with gout. JAMA 328:440–450. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.11390

van Durme CMPG, Wechalekar MD, Buchbinder R et al (2014) Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for acute gout. Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD010120. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010120.pub2

Wechalekar MD, Vinik O, Moi JHY et al (2014) The efficacy and safety of treatments for acute gout: results from a series of systematic literature reviews including Cochrane reviews on intraarticular glucocorticoids, colchicine, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, and interleukin-1 inhibitors. J Rheumatol Suppl 92:15–25. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.140458

Schlesinger N, Detry MA, Holland BK et al (2002) Local ice therapy during bouts of acute gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol 29:331–334

Janssen CA, Oude Voshaar MAH, Vonkeman HE et al (2019) Anakinra for the treatment of acute gout flares: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, active-comparator, non-inferiority trial. Rheumatology (Oxford). https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/key402

So A, De Smedt T, Revaz S, Tschopp J (2007) A pilot study of IL-1 inhibition by anakinra in acute gout. Arthritis Res Ther 9:R28. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar2143

Ottaviani S, Moltó A, Ea H-K et al (2013) Efficacy of anakinra in gouty arthritis: a retrospective study of 40 cases. Arthritis Res Ther 15:R123. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar4303

Loustau C, Rosine N, Forien M et al (2018) Effectiveness and safety of anakinra in gout patients with stage 4–5 chronic kidney disease or kidney transplantation: a multicentre, retrospective study. Jt Bone Spine 85:755–760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbspin.2018.03.015

Ghosh P, Cho M, Rawat G et al (2013) Treatment of acute gouty arthritis in complex hospitalized patients with anakinra. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 65:1381–1384. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21989

Chen K, Fields T, Mancuso CA et al (2010) Anakinra’s efficacy is variable in refractory gout: report of ten cases. Semin Arthritis Rheum 40:210–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2010.03.001

Terkeltaub RA, Schumacher HR, Carter JD et al (2013) Rilonacept in the treatment of acute gouty arthritis: a randomized, controlled clinical trial using indomethacin as the active comparator. Arthritis Res Ther 15:R25. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar4159

So A, De Meulemeester M, Pikhlak A et al (2010) Canakinumab for the treatment of acute flares in difficult-to-treat gouty arthritis: results of a multicenter, phase II, dose-ranging study. Arthritis Rheum 62:3064–3076. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.27600

Schlesinger N, De Meulemeester M, Pikhlak A et al (2011) Canakinumab relieves symptoms of acute flares and improves health-related quality of life in patients with difficult-to-treat Gouty Arthritis by suppressing inflammation: results of a randomized, dose-ranging study. Arthritis Res Ther 13:R53. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar3297

Schlesinger N, Alten RE, Bardin T et al (2012) Canakinumab for acute gouty arthritis in patients with limited treatment options: results from two randomised, multicentre, active-controlled, double-blind trials and their initial extensions. Ann Rheum Dis 71:1839–1848. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200908

Borstad GC, Bryant LR, Abel MP et al (2004) Colchicine for prophylaxis of acute flares when initiating allopurinol for chronic gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol 31:2429–2432

Yamanaka H, Tamaki S, Ide Y et al (2018) Stepwise dose increase of febuxostat is comparable with colchicine prophylaxis for the prevention of gout flares during the initial phase of urate-lowering therapy: results from FORTUNE-1, a prospective, multicentre randomised study. Ann Rheum Dis 77:270–276. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211574

Wortmann RL, Macdonald PA, Hunt B, Jackson RL (2010) Effect of prophylaxis on gout flares after the initiation of urate-lowering therapy: analysis of data from three phase III trials. Clin Ther 32:2386–2397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.01.008

Niel E, Scherrmann J-M (2006) Colchicine today. Jt bone spine 73:672–678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbspin.2006.03.006

Terkeltaub RA (2009) Colchicine update: 2008. Semin Arthritis Rheum 38:411–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2008.08.006

Terkeltaub RA, Furst DE, Digiacinto JL et al (2011) Novel evidence-based colchicine dose-reduction algorithm to predict and prevent colchicine toxicity in the presence of cytochrome P450 3A4/P-glycoprotein inhibitors. Arthritis Rheum 63:2226–2237. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.30389

Schlesinger N, Mysler E, Lin H-Y et al (2011) Canakinumab reduces the risk of acute gouty arthritis flares during initiation of allopurinol treatment: results of a double-blind, randomised study. Ann Rheum Dis 70:1264–1271. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2010.144063

Schumacher HRJ, Evans RR, Saag KG et al (2012) Rilonacept (interleukin-1 trap) for prevention of gout flares during initiation of uric acid-lowering therapy: results from a phase III randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, confirmatory efficacy study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 64:1462–1470. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21690

Mitha E, Schumacher HR, Fouche L et al (2013) Rilonacept for gout flare prevention during initiation of uric acid-lowering therapy: results from the PRESURGE-2 international, phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Rheumatology (Oxford) 52:1285–1292. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/ket114

Sundy JS, Schumacher HR, Kivitz A et al (2014) Rilonacept for gout flare prevention in patients receiving uric acid-lowering therapy: results of RESURGE, a phase III, international safety study. J Rheumatol 41:1703–1711. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.131226

Faruque LI, Ehteshami-Afshar A, Wiebe N et al (2013) A systematic review and meta-analysis on the safety and efficacy of febuxostat versus allopurinol in chronic gout. Semin Arthritis Rheum 43:367–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.05.004

Sriranganathan MK, Vinik O, Falzon L et al (2014) Interventions for tophi in gout: a Cochrane systematic literature review. J Rheumatol Suppl 92:63–69. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.140464

Ye P, Yang S, Zhang W et al (2013) Efficacy and tolerability of febuxostat in hyperuricemic patients with or without gout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Ther 35:180–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2012.12.011

Sundy JS, Baraf HSB, Yood RA et al (2011) Efficacy and tolerability of pegloticase for the treatment of chronic gout in patients refractory to conventional treatment: two randomized controlled trials. JAMA 306:711–720. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1169

Tausche A-K, Alten R, Dalbeth N et al (2017) Lesinurad monotherapy in gout patients intolerant to a xanthine oxidase inhibitor: a 6 month phase 3 clinical trial and extension study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 56:2170–2178. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kex350

Schumacher HR, Becker MA, Wortmann RL et al (2008) Effects of febuxostat versus allopurinol and placebo in reducing serum urate in subjects with hyperuricemia and gout: a 28-week, phase III, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group trial. Arthritis Rheum 59. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.24209

Becker MA, Schumacher HR, Wortmann RL et al (2005) Febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with hyperuricemia and gout. N Engl J Med 353:2450–2461. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa050373

Baraf HSB, Becker MA, Gutierrez-Urena SR et al (2013) Tophus burden reduction with pegloticase: results from phase 3 randomized trials and open-label extension in patients with chronic gout refractory to conventional therapy. Arthritis Res Ther 15:R137. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar4318

Marchini GS, Sarkissian C, Tian D et al (2013) Gout, stone composition and urinary stone risk: a matched case comparative study. J Urol 189:1334–1339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2012.09.102

Goldfarb DS, MacDonald PA, Gunawardhana L et al (2013) Randomized controlled trial of febuxostat versus allopurinol or placebo in individuals with higher urinary uric acid excretion and calcium stones. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8:1960–1967. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.01760213

Ettinger B, Tang A, Citron JT et al (1986) Randomized trial of allopurinol in the prevention of calcium oxalate calculi. N Engl J Med 315:1386–1389. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198611273152204

Dalbeth N, Saag KG, Palmer WE et al (2017) Effects of febuxostat in early gout: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arthritis Rheumatol (Hoboken, NJ) 69:2386–2395. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.40233

Krishnan E (2012) Reduced glomerular function and prevalence of gout: NHANES 2009–10. PLoS One 7. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0050046

Siu YP, Leung KT, Tong MKH, Kwan TH (2006) Use of allopurinol in slowing the progression of renal disease through its ability to lower serum uric acid level. Am J Kidney Dis 47:51–59. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.10.006

Goicoechea M, De Vinuesa SG, Verdalles U et al (2010) Effect of allopurinol in chronic kidney disease progression and cardiovascular risk. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5:1388–1393. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.01580210

Levy GD, Rashid N, Niu F, Cheetham TC (2014) Effect of urate-lowering therapies on renal disease progression in patients with hyperuricemia. J Rheumatol 41:955–962. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.131159

Lu C-C, Wu S-K, Chen H-Y et al (2014) Clinical characteristics of and relationship between metabolic components and renal function among patients with early-onset juvenile tophaceous gout. J Rheumatol 41:1878–1883. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.131240

Dalbeth N, House ME, Horne A, Taylor WJ (2013) Reduced creatinine clearance is associated with early development of subcutaneous tophi in people with gout. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 14:363. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-14-363

Wu EQ, Patel PA, Mody RR et al (2009) Frequency, risk, and cost of gout-related episodes among the elderly: does serum uric acid level matter? J Rheumatol 36:1032–1040. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.080487

Abhishek A, Valdes AM, Zhang W, Doherty M (2016) Association of serum uric acid and disease duration with frequent gout attacks: a case-control study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 68:1573–1577. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22855

Singh JA, Reddy SG, Kundukulam J (2011) Risk factors for gout and prevention: a systematic review of the literature. Curr Opin Rheumatol 23:192–202. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283438e13

Campion EW, Glynn RJ, DeLabry LO (1987) Asymptomatic hyperuricemia. Risks and consequences in the Normative Aging Study. Am J Med 82:421–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9343(87)90441-4

Shoji A, Yamanaka H, Kamatani N (2004) A retrospective study of the relationship between serum urate level and recurrent attacks of gouty arthritis: evidence for reduction of recurrent gouty arthritis with antihyperuricemic therapy. Arthritis Rheum 51:321–325. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.20405

Ferraz MB, O’Brien B (1995) A cost effectiveness analysis of urate lowering drugs in nontophaceous recurrent gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol 22:908–914

Yu TF, Gutman AB (1961) Efficacy of colchicine prophylaxis in gout. Prevention of recurrent gouty arthritis over a mean period of five years in 208 gouty subjects. Ann Intern Med 55:179–192. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-55-2-179

Bhole V, de Vera M, Rahman MM et al (2010) Epidemiology of gout in women: fifty-two-year followup of a prospective cohort. Arthritis Rheum 62:1069–1076. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.27338

Yu K-H, Luo S-F (2003) Younger age of onset of gout in Taiwan. Rheumatology (Oxford) 42:166–170. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keg035

Matsuo H, Ichida K, Takada T et al (2013) Common dysfunctional variants in ABCG2 are a major cause of early-onset gout. Sci Rep 3:2014. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02014

Yamanaka H (2011) Gout and hyperuricemia in young people. Curr Opin Rheumatol 23:156–160. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283432d35

Wan W, Xu X, Zhao DB et al (2015) Polymorphisms of uric transporter proteins in the pathogenesis of gout in a Chinese Han population. Genet Mol Res 14:2546–2550. https://doi.org/10.4238/2015.March.30.13

Bardin T (2015) Hyperuricemia starts at 360 micromoles (6 mg/dL). Jt Bone Spine 82:141–143

Pascual E, Sivera F (2007) Time required for disappearance of urate crystals from synovial fluid after successful hypouricaemic treatment relates to the duration of gout. Ann Rheum Dis 66:1056–1058. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2006.060368

Perez-Ruiz F, Lioté F (2007) Lowering serum uric acid levels: what is the optimal target for improving clinical outcomes in gout? Arthritis Rheum 57:1324–1328. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.23007

Perez-Ruiz F, Calabozo M, Pijoan JI et al (2002) Effect of urate-lowering therapy on the velocity of size reduction of tophi in chronic gout. Arthritis Rheum 47:356–360. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.10511

Perez-Ruiz F, Herrero-Beites AM, Carmona L (2011) A two-stage approach to the treatment of hyperuricemia in gout: the “dirty dish” hypothesis. Arthritis Rheum 63:4002–4006. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.30649

Stamp LK, Chapman PT, Barclay ML et al (2017) A randomised controlled trial of the efficacy and safety of allopurinol dose escalation to achieve target serum urate in people with gout. Ann Rheum Dis 76:1522–1528. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210872.

Cortese M, Riise T, Engeland A et al (2018) Urate and the risk of Parkinson’s disease in men and women. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 52:76–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2018.03.026

Engel B, Gomm W, Broich K et al (2018) Hyperuricemia and dementia – a case-control study. BMC Neurol 18:131. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-018-1136-y

Tassaneeyakul W, Jantararoungtong T, Chen P et al (2009) Strong association between HLA-B*5801 and allopurinol-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in a Thai population. Pharmacogenet Genomics 19:704–709. https://doi.org/10.1097/FPC.0b013e328330a3b8

Stamp LK, Day RO, Yun J (2016) Allopurinol hypersensitivity: investigating the cause and minimizing the risk. Nat Rev Rheumatol 12:235–242. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2015.132

Saito Y, Stamp LK, Caudle KE et al (2016) Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guidelines for human leukocyte antigen B (HLA-B) genotype and allopurinol dosing: 2015 update. Clin Pharmacol Ther 99:36–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.161

Hershfield MS, Callaghan JT, Tassaneeyakul W et al (2013) Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for human leukocyte antigen-B genotype and allopurinol dosing. Clin Pharmacol Ther 93:153–158. https://doi.org/10.1038/clpt.2012.209

Dean L, Kane M (2012) Allopurinol Therapy and HLA-B*58:01 Genotype. In: Pratt VM, Scott SA, Pirmohamed M et al (eds) Bethesda (MD)

Gonzalez-Galarza FF, McCabe A, Dos SEJM et al (2020) Allele frequency net database (AFND) 2020 update: gold-standard data classification, open access genotype data and new query tools. Nucleic Acids Res 48:D783–D788. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkz1029

Chiu MLS, Hu M, Ng MHL et al (2012) Association between HLA-B*58:01 allele and severe cutaneous adverse reactions with allopurinol in Han Chinese in Hong Kong. Br J Dermatol 167:44–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10894.x

Yu K-H, Yu C-Y, Fang Y-F (2017) Diagnostic utility of HLA-B*5801 screening in severe allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Rheum Dis 20:1057–1071. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185X.13143

Jutkowitz E, Dubreuil M, Lu N et al (2017) The cost-effectiveness of HLA-B*5801 screening to guide initial urate-lowering therapy for gout in the United States. Semin Arthritis Rheum 46:594–600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.10.009

Saokaew S, Tassaneeyakul W, Maenthaisong R, Chaiyakunapruk N (2014) Cost-effectiveness analysis of HLA-B*5801 testing in preventing allopurinol-induced SJS/TEN in Thai population. PLoS One 9:e94294. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0094294

Yang C-Y, Chen C-H, Deng S-T et al (2015) Allopurinol use and risk of fatal hypersensitivity reactions: a nationwide population-based study in Taiwan. JAMA Intern Med 175:1550–1557. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.3536

Chung W-H, Chang W-C, Stocker SL et al (2015) Insights into the poor prognosis of allopurinol-induced severe cutaneous adverse reactions: the impact of renal insufficiency, high plasma levels of oxypurinol and granulysin. Ann Rheum Dis 74:2157–2164. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205577

Fam AG, Dunne SM, Iazzetta J, Paton TW (2001) Efficacy and safety of desensitization to allopurinol following cutaneous reactions. Arthritis Rheum 44:231–238. https://doi.org/10.1002/1529-0131(200101)44:1%3c231::AID-ANR30%3e3.0.CO;2-7

Stamp LK, Taylor WJ, Jones PB et al (2012) Starting dose is a risk factor for allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome: a proposed safe starting dose of allopurinol. Arthritis Rheum 64:2529–2536. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.34488

Wong CSM, Yeung CK, Chan CY et al (2022) HLA-B*58:01 screening to prevent allopurinol-induced severe cutaneous adverse reactions in Chinese patients with chronic kidney disease. Arch Dermatol Res 314:651–659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-021-02258-3

Kimura K, Hosoya T, Uchida S et al (2018) Febuxostat therapy for patients with stage 3 CKD and asymptomatic hyperuricemia: a randomized trial. Am J Kidney Dis 72:798–810. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.06.028

Baker JF, Krishnan E, Chen L, Schumacher HR (2005) Serum uric acid and cardiovascular disease: recent developments, and where do they leave us? Am J Med 118:816–826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.03.043

Pérez Ruiz F, Richette P, Stack AG et al (2019) Failure to reach uric acid target of <0.36 mmol/L in hyperuricaemia of gout is associated with elevated total and cardiovascular mortality. RMD Open 5:e001015. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2019-001015

Zhang M, Solomon DH, Desai RJ et al (2018) Assessment of cardiovascular risk in older patients with gout initiating febuxostat versus allopurinol: population-based cohort study. Circulation 138:1116–1126. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.033992

Choi H, Neogi T, Stamp L et al (2018) New perspectives in rheumatology: implications of the cardiovascular safety of febuxostat and allopurinol in patients with gout and cardiovascular morbidities trial and the associated food and drug administration public safety alert. Arthritis Rheumatol (Hoboken, NJ) 70:1702–1709. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.40583

Lin T-C, Hung LY, Chen Y-C et al (2019) Effects of febuxostat on renal function in patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 98:e16311. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000016311

Sarvepalli PS, Fatima M, Quadri AK et al (2018) Study of therapeutic efficacy of febuxostat in chronic kidney disease stage IIIA to stage VD. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transplant Off Publ Saudi Cent Organ Transplant Saudi Arab 29:1050–1056. https://doi.org/10.4103/1319-2442.243953

Kim S-H, Lee S-Y, Kim J-M, Son C-N (2020) Renal safety and urate-lowering efficacy of febuxostat in gout patients with stage 4–5 chronic kidney disease not yet on dialysis. Korean J Intern Med 35:998–1003. https://doi.org/10.3904/kjim.2018.423

Peng Y-L, Tain Y-L, Lee C-T et al (2020) Comparison of uric acid reduction and renal outcomes of febuxostat vs allopurinol in patients with chronic kidney disease. Sci Rep 10:10734. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67026-1

Liu X, Liu K, Sun Q et al (2018) Efficacy and safety of febuxostat for treating hyperuricemia in patients with chronic kidney disease and in renal transplant recipients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Exp Ther Med 16:1859–1865. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2018.6367

Shibagaki Y, Ohno I, Hosoya T, Kimura K (2014) Safety, efficacy and renal effect of febuxostat in patients with moderate-to-severe kidney dysfunction. Hypertens Res 37:919–925. https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2014.107

Pui K, Gow PJ, Dalbeth N (2013) Efficacy and tolerability of probenecid as urate-lowering therapy in gout; clinical experience in high-prevalence population. J Rheumatol 40:872–876. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.121301

Lee M-HH, Graham GG, Williams KM, Day RO (2008) A benefit-risk assessment of benzbromarone in the treatment of gout. Was its withdrawal from the market in the best interest of patients? Drug Saf 31:643–665. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200831080-00002

Kim SC, Neogi T, Kang EH et al (2018) Cardiovascular risks of probenecid versus allopurinol in older patients with gout. J Am Coll Cardiol 71:994–1004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2017.12.052

Reinders MK, van Roon EN, Jansen TLTA et al (2009) Efficacy and tolerability of urate-lowering drugs in gout: a randomised controlled trial of benzbromarone versus probenecid after failure of allopurinol. Ann Rheum Dis 68:51–56. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2007.083071

Reinders MK, van Roon EN, Houtman PM et al (2007) Biochemical effectiveness of allopurinol and allopurinol-probenecid in previously benzbromarone-treated gout patients. Clin Rheumatol 26:1459–1465. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-006-0528-3

Stamp LK, Chapman PT, Barclay M et al (2017) Allopurinol dose escalation to achieve serum urate below 6 mg/dL: an open-label extension study. Ann Rheum Dis 76:2065–2070. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211873

Stamp LK, Chapman PT, Barclay M et al (2017) The effect of kidney function on the urate lowering effect and safety of increasing allopurinol above doses based on creatinine clearance: a post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Res Ther 19:283. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-017-1491-x

Vázquez-Mellado J, Morales EM, Pacheco-Tena C, Burgos-Vargas R (2001) Relation between adverse events associated with allopurinol and renal function in patients with gout. Ann Rheum Dis 60:981–983. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.60.10.981

White WB, Saag KG, Becker MA et al (2018) Cardiovascular safety of febuxostat or allopurinol in patients with gout. N Engl J Med 378:1200–1210. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1710895

Mackenzie IS, Ford I, Nuki G et al (2020) Long-term cardiovascular safety of febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with gout (FAST): a multicentre, prospective, randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet (London, England) 396:1745–1757. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32234-0

Choi H, Neogi T, Stamp L et al (2018) Implications of the cardiovascular safety of febuxostat and allopurinol in patients with gout and cardiovascular morbidities (CARES) trial and associated FDA public safety alert. Arthritis Rheumatol (Hoboken, NJ). https://doi.org/10.1002/art.40583

McCormick N, Rai SK, Lu N et al (2020) Estimation of primary prevention of gout in men through modification of obesity and other key lifestyle factors. JAMA Netw Open 3:e2027421. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMANETWORKOPEN.2020.27421

Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, Curhan G (2005) Obesity, weight change, hypertension, diuretic use, and risk of gout in men: the health professionals follow-up study. Arch Intern Med 165:742–748. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.165.7.742

Choi HK, Liu S, Curhan G (2005) Intake of purine-rich foods, protein, and dairy products and relationship to serum levels of uric acid: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum 52:283–289. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.20761

Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW et al (2004) Purine-rich foods, dairy and protein intake, and the risk of gout in men. N Engl J Med 350:1093–1103. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa035700

Faller J, Fox IH (1982) Ethanol-induced hyperuricemia: evidence for increased urate production by activation of adenine nucleotide turnover. N Engl J Med 307:1598–1602. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198212233072602

Gibson T, Rodgers AV, Simmonds HA, Toseland P (1984) Beer drinking and its effect on uric acid. Br J Rheumatol 23:203–209. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/23.3.203

Puig JG, Fox IH (1984) Ethanol-induced activation of adenine nucleotide turnover. Evidence for a role of acetate. J Clin Invest 74:936–941. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI111512

Yamamoto T, Moriwaki Y, Takahashi S et al (2002) Effect of beer on the plasma concentrations of uridine and purine bases. Metabolism 51:1317–1323. https://doi.org/10.1053/meta.2002.34041

Choi HK, Curhan G (2004) Beer, liquor, and wine consumption and serum uric acid level: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum 51:1023–1029. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.20821

Li R, Yu K, Li C (2018) Dietary factors and risk of gout and hyperuricemia: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 27:1344–1356. https://doi.org/10.6133/apjcn.201811_27(6).0022

Ka T, Moriwaki Y, Takahashi S et al (2005) Effects of long-term beer ingestion on plasma concentrations and urinary excretion of purine bases. Horm Metab Res = Horm und Stoffwechselforsch = Horm Metab 37:641–645. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2005-870540

Moriwaki Y, Ka T, Takahashi S et al (2006) Effect of beer ingestion on the plasma concentrations and urinary excretion of purine bases: one-month study. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 25:1083–1085. https://doi.org/10.1080/15257770600893990

Caliceti C, Calabria D, Roda A, Cicero AFG (2017) Fructose intake, serum uric acid, and cardiometabolic disorders: a critical review. Nutrients 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9040395

Choi HK, Curhan G (2008) Soft drinks, fructose consumption, and the risk of gout in men: prospective cohort study. BMJ 336:309–312. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39449.819271.BE

Hoare C, Li Wan Po A, Williams H (2000) Systematic review of treatments for atopic eczema. Health Technol Assess (Rockv) 4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0190-9622(02)61464-1

Nielsen SM, Bartels EM, Henriksen M et al (2017) Weight loss for overweight and obese individuals with gout: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Ann Rheum Dis 76:1870–1882. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211472

Ghang B-Z, Lee JS, Choi J et al (2022) Increased risk of cardiovascular events and death in the initial phase after discontinuation of febuxostat or allopurinol: another story of the CARES trial. RMD Open 8:e001944. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2021-001944

Saag KG, Becker MA, White WB et al (2022) Evaluation of the relationship between serum urate levels, clinical manifestations of gout, and death from cardiovascular causes in patients receiving febuxostat or allopurinol in an outcomes trial. Arthritis Rheumatol (Hoboken, NJ) 74:1593–1601. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.42160

Choi HK, Soriano LC, Zhang Y, Rodríguez LAG (2012) Antihypertensive drugs and risk of incident gout among patients with hypertension: population based case-control study. BMJ 344:d8190. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d8190

Caspi D, Lubart E, Graff E et al (2000) The effect of mini-dose aspirin on renal function and uric acid handling in elderly patients. Arthritis Rheum 43:103–108. https://doi.org/10.1002/1529-0131(200001)43:1%3c103::AID-ANR13%3e3.0.CO;2-C

Zhang Y, Neogi T, Chen C et al (2014) Low-dose aspirin use and recurrent gout attacks. Ann Rheum Dis 73:385–390. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202589

Nardin M, Verdoia M, Pergolini P et al (2016) Serum uric acid levels during dual antiplatelet therapy with ticagrelor or clopidogrel: results from a single-centre study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 26:567–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2016.03.001

Camm AJ, Accetta G, Ambrosio G et al (2017) Evolving antithrombotic treatment patterns for patients with newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation. Heart 103:307–314. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2016-309832

Würzner G, Gerster JC, Chiolero A et al (2001) Comparative effects of losartan and irbesartan on serum uric acid in hypertensive patients with hyperuricaemia and gout. J Hypertens 19:1855–1860. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004872-200110000-00021

Chanard J, Toupance O, Lavaud S et al (2003) Amlodipine reduces cyclosporin-induced hyperuricaemia in hypertensive renal transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant Off Publ Eur Dial Transpl Assoc - Eur Ren Assoc 18:2147–2153. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfg341

Shahinfar S, Simpson RL, Carides AD et al (1999) Safety of losartan in hypertensive patients with thiazide-induced hyperuricemia. Kidney Int 56:1879–1885. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00739.x

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the HKSR full members and those who participated in the Delphi exercise. We also would like to thank MIMS for their editorial support in the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical standards

The manuscript does not contain clinical studies or patient data.

Disclosures

None.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yip, R.M., Cheung, T.T., So, H. et al. The Hong Kong Society of Rheumatology consensus recommendations for the management of gout. Clin Rheumatol 42, 2013–2027 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-023-06578-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-023-06578-9