Abstract

Background

The early detection of psoriatic arthritis (PSA) poses a challenge to rheumatologists, even when their diagnosis is aided by sonography. In order to facilitate early detection of PSA among patients with psoriasis (PSO), we retrospectively analyzed of the relationships between serological markers and comorbidities in 629 psoriatic patients, 102 of which had PSA, while the other 527 had PSO.

Results

Serological markers were found not to be useful in distinguishing between PSA and PSO (p > 0.05 for all comparisons). The prevalence rate of PSA among PSO patients was around 19.4%. Two components of metabolic syndrome—hyperlipidemia (2.94%) and gout (4.9%)—were significantly more prevalent in PSA patients than in PSO patients (p < 0.05). The odds ratio for PSA is 15.94 in patients with hyperlipidemia with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 1.64–154.80; meanwhile, the odds ratio for PSA is 3.83 in patients with gout with a 95% CI of 1.19–12.31. Allergic rhinitis (5.88%) was more prevalent in PSA patients than in PSO patients (p < 0.01). The odds ratio was 8.17 in patients with allergic rhinitis with a 95% CI of 2.26–29.50. Plasma hs-miR-210-3p distinguishes PSA from PSO, and its levels can also be distinguished from PSA after treated with anti-TNFα biologics agents (both p < 0.05).

Conclusions

No clinical available serology markers, but hyperlipidemia, gout, axial spondylopathy (inflammatory back pain), or allergic rhinitis, could differentiate between psoriatic arthritis from psoriasis. Plasma hs-miR-210-3p and comorbidities may differentiate psoriatic arthritis from psoriasis.

Key Points • Clinical manifestations and comorbidities are different between psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis only patients. • Traditional serology markers are similar between psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis-only patients. • Plasma hs-miR-210-3p distinguishes PSA from PSO, and its levels can also be distinguished from PSA after treated with anti-TNFα biologics agents in our study. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

The early detection and diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis (PSA) pose a challenge to rheumatologists [1], even when aided by sonography [2]. The MAdrid Sonographic Enthesitis Index (MASEI) has a sensitivity of only 30% for diagnosing PSA. An update of the treat to target concept of a Canadian dermatologic expert suggested looking beyond the skin [3]. Such treat to target concept requires the early diagnosis and treatment of PSA [4, 5]. Using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnostic codes in a hospital database, we retrospectively identified and analyzed the medical records of all patients with psoriasis (PSO) or PSA but without any autoimmune diseases. To support our proposed concept, we carried out a preliminary study and prospectively compared more than 150 plasma microRNAs from four PSA patients with four lupus patients, three osteoarthritis (OA), and three PSO patients. One recent study reported that the prevalence rate of PSA is about 17% among PSO patients in dermatology clinics [6]. By comparing the relationships between serological markers and comorbidities with PSO and PSA, we attempted to identify markers and clinical characteristics that may aid the early diagnosis of PSA among PSO patients. We further demonstrated in our preliminary study that the clinical presentation may hint at serology and pathophysiology diagnosis.

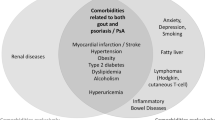

PSO is a systemic disease that involves the skin [7], joints [8, 9], nails, kidneys [10], vascular system [11], and heart [12] and may be related to the development of cancer [13]. A previous large retrospective study using the National Insurance database indicated that PSO has dozens of comorbidities when compared to normal controls [14]. Other previous studies have shown that PSO and PSA are difficult to diagnose based on serological findings; however, only one report focuses on using autoantibodies against extractable nuclear antigens (anti-ENA) in PSO [15], but none has focused on it in PSA patients. We collected all available data on clinical anti-ENA antibody status among PSO and PSA patients and investigated the correlations between disease status and anti-ENA results. Furthermore, we gathered information on the spectrum of clinical conditions that may be associated with PSO, including dermatitis [16], pyoderma [17, 18], diabetes [19, 20], hypertension [21], hepatitis [22, 23], gout [24, 25], axial spondylopathy [26], dyslipidemia, allergic rhinitis, bronchitis, hepatitis B virus (HBV) carrier status [27], and previous hepatitis C infection among anti-HCV–positive persons [28].

In this prospective proof-of-concept preliminary study, plasma was collected from patients with osteoarthritis (OA), PSO, PSA, and SLE for microRNA analysis. Serology microRNA arrays can reflect some inflammatory pathways in several aspects, instead of just the very limited clinical tests currently available. Since the current situation has limited clinical tests available, the aim of this study is to find a reference for selecting particular PSA patients for earlier clinical diagnosis.

Methods

Patients

The first part of our study is a retrospective chart review that describes data from all patients over the age of 20 years who had been diagnosed with PSO or PSA between July 1, 2000 and December 31, 2014 at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Kaohsiung (CGMH-KS) Medical Center. CGMH-KS is a tertiary care referral center located in Kaohsiung County, which is located in southern Taiwan, and serves a population of approximately two million people. We excluded any patients with a concurrent diagnosis of another autoimmune disease, including systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, sicca syndrome, dermatomyositis, and polymyositis. The study was carried out using a protocol approved by the Ethics Committee of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (Institutional Review Board numbers: 102-4669B and 104-5733B). Informed consent was not obtained from the individual patients in the retrospective part of study. Prior to analysis, the medical records/data were anonymized and de-identified.

The second prospective study only has male patients which were divided into several subgroups: four male patients with PSA, three male patients with PSO, four male patients with SLE (as disease controls), and three male patients with on osteoarthritis (OA, as non-inflammatory controls). We collected plasma from all these patients for microRNA array analysis. We obtained informed consent from each patient, and the study was conducted according to a protocol approved by the Ethics Committee of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (Institutional Review Board number: 104-5733B).

Data collection

Patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics were analyzed, including age, gender, leukocyte differential count, hemoglobin, hematocrit, platelet count, creatinine, uric acid, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sediment rate, rheumatoid factor, lipid profile, anti-nuclear autoantibodies, anti-ENA autoantibodies, anti-phospholipid autoantibodies, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies, anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA), hepatitis B surface antigen, anti-hepatitis C antibody, and comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, gout, axial spondylopathy, asthma, bronchitis, allergic dermatitis, etc.).

MicroRNA preparation

Samples were centrifuged at 1000×g for 10 min to pellet cellular debris, and we used the supernatant for RNA extraction. We extracted total RNA from 300 μL fluids using the miRNeasy kit (Qiagen) as previously described by Weber et al. [29]. All the microRNA levels were confirmed with real-time PCR with PanelChip™ qPCR on QuarkBio PanelStation™.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics were reported as simple descriptive statistics. In univariate analysis, categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test, while continuous variables were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test for non-parametric data with a non-normal distribution and the t test for normally distributed data. MicroRNA plasma levels were calculated between groups using ANOVA and post hoc analysis with the Bonferroni method. We performed multivariate analysis by estimating odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using a logistic regression model. The chi-square test was used to compare different diseases between each group and examine the prevalence of comorbidities between PSO and PSA patients according to level of disease severity. Statistical significance was defined as a p value of less than 0.05. All analyses were performed using the SPSS software program, version 15.5 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Results

Demographic characteristics of patients

In total, 629 patients (102 with PSA and 527 with PSO) were identified during the period of July 1, 2000 through December 31, 2014. PSA diagnoses were confirmed by chart review or the presence of a relevant ICD-9-CM code diagnosed by a rheumatologist. The prevalence rate of PSA among PSO patients was 19.35%.

The two subgroups did not significantly differ with regard to total leukocyte count, platelets, hemoglobin, hematocrit, lipoprotein profile, inflammation markers (C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sediment rate), titers of anti-nuclear antibodies, or rheumatoid factor (p > 0.05 for all comparisons) (Table 1).

Anti-ENA autoantibodies, anti-phospholipid autoantibodies, and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies in PSO and PSA patients

Data regarding anti-ENA levels were available for 41 patients (18 with PSA and 23 with PSO). We reviewed charts to determine levels of anti-ENA autoantibodies (including anti-Ro, anti-La, anti-U1 RNP, anti-Sm, anti-Scl 70, and anti-Jo 1), anti-phospholipid autoantibodies (anti-beta 2 glycoprotein 1 and anti-cardiolipin IgG or IgM), anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies, and ACPA. Anti-Sm and anti-U1 RNP were significantly higher in PSO patients (p < 0.05). However, none of the aforementioned autoantibodies was independently associated with PSO after multivariate logistic regression analysis (p = 1.00) (Supplementary Table 1).

Comparison of the correlation coefficiencies between psoriasis comorbidities and psoriatic arthritis comorbidities

Using ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes, we analyzed each of the relationships between hypertension, gout, axial spondylopathy, asthma, bronchitis, allergic dermatitis, and pyoderma with PSO or PSA status (Table 2). Various diseases were happening significantly higher in PSA than in PSO, including hyperlipidemia, gout, axial spondylopathy, and allergic rhinitis (p < 0.05) (Table 2). The odds ratios for a patient with PSA to get any comorbidity of the following diseases, comparing to a patient with PSO, were listed as the following: 15.94 times to have hyperlipidemia with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 1.64–154.80, 3.83 times to have gout with a 95% CI of 1.19–12.31, 1.12 times to have axial spondylopathy with a 95% CI of 1.05–1.20, and 8.17 times to have allergic rhinitis with a 95% CI of 2.26–29.50 (Table 2).

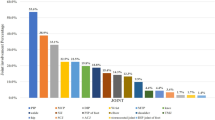

Heatmap of PanelChip™ qPCR on QuarkBio PanelStation™ and comparison between PSA and SLE patients in the prospective proof-of-concept preliminary study

The resulting heatmap of PanelChip™ qPCR on the QuarkBio PanelStation™ is shown in Fig. 1. The heatmap includes the distribution patterns of the three different diseases, as well as OA as the non-inflammatory controls. The diseases include PSO, PSA, and SLE, and the heatmap clustering shows all samples based on microRNA expression pattern.

We compared 128 plasma microRNA Ct levels between male PSO, male PSA, and male PSA patients. The Ct of hs-miR210-3p is statistically lower in male PSA patients, before biologics treatment, compared to male PSO patients (p = 0.04) (Fig. 2; Table 3). The Ct levels of hs-miR210-3p in male PSA patients were comparable with male PSO patients after they were treated with anti-TNFα agents. Treatment with anti-TNFα agents significantly increased hs-miR210-3p Ct levels in male PSA patients (p = 0.04) (Fig. 2; Table 3).

Discussion

The under-diagnosis of PSA among persons with psoriasis not only delays treatment but also increases the risk of joint damage [30]. In one study, the rate of PSA under-diagnosis was estimated to be about 9% [31]. Early diagnosis of PSA could also increase awareness in doctors to treat comorbidities. Upon comparing PSO and PSA patients, a Turkish study found that hypertension was significantly more prevalent in PSA patients [32]. Our present results also show a higher prevalence rate of hypertension in PSA patients (3.92%) than in PSO patients (1.33%), but the difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.09 with odds ratio 3.03, 95% CI 0.87–10.55). The hazard ratio of hypertension was higher for PSA than for PSO in one large US cohort study [24]. When talking about gout, our results are in line with previous study [24], with an odds ratio of 3.83 and a 95%CI of 1.19–12.31 for PSA, which is significantly higher than PSO patients (p = 0.03).

Coronary heart disease and metabolic syndrome are major comorbidities of PSA [33]. A large retrospective study in Europe reported that PSA was associated with dyslipidemia, diabetes, hypertension, axial spondylopathy, and rheumatoid arthritis [34]. We obtained similar results, which have an odds ratio of 3.83 and a 95% CI of 1.19–12.31 for PSA compared to PSO in patients with gout (p = 0.03), an odds ratio of 15.94 and a 95% CI of 1.64–154.80 for PSA compared to PSO in patients with hyperlipidemia (p = 0.02), and an odds ratio of 1.12 and a 95% CI of 1.05–1.20 for PSA compared to PSO in patients with axial spondylopathy (p < 0.01).

Psoriasis has been associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in a prior meta-analysis [35]. In the present study, the prevalence rate of non-B, non-C hepatitis was higher among PSA patients (2.94%) than PSO patients (0.95%), but the difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.13) (Table 1).

The prevalence rate of allergic rhinitis was significantly higher in patients with PSA than in those with PSO (p < 0.01). The odds ratio is 8.17 with a 95% CI of 2.26–29.50 for PSA compared to PSO in patients with allergic rhinitis (p < 0.01). A previous large cohort study from Taiwan compared 51,800 PSO patients with normal controls using the National Insurance database and similarly demonstrated that PSO has a significant association with allergic rhinitis [14]. PSO and PSA are likely both associated with allergic rhinitis according to the aforementioned PSO study [14] and our current report (Table 2).

Allergic diseases are Th2-polarized diseases [36], whereas psoriasis is a Th17 disease, in general speaking, but could be a Th9-polarized disease in the gut [36, 37]. This transition may explain why allergic skin disease does not coexist with PSO in our cohort, but whether the Th9 links between the Th2 [38] and Th17 [39] pathogeneses need to be further investigated. Another explanation is that IL17E, also known as IL25, could propagate production of IL-4 and IL-13 in different organs, which stimulate the expansion of eosinophils [40], and link between allergic disease and psoriatic disease. Psoriatic arthritis has only few biomarkers [41, 42], but we failed to identify in anti-ENA markers (Supplementary Table 1).

In this prospective proof-of-concept preliminary study, we collected plasma from three male PSO, four male PSA, three male OA, and four male SLE patients for microRNA analysis. The distribution pattern of PSA in the microRNA array is divided into right and left parts in the heatmap (Fig. 1). Among the right part, these PSA patients mostly have simple clinical symptoms, such as arthritis, without other systemic diseases, and their clinical situations are very similar to lupus patients B043 and R017 with relatively low disease activity (SLEDAI = 4). The left-part PSA patients have more complex systemic diseases. The distribution pattern of the microRNA from the right-part PSA patients in the heatmap is closer to a normal control patient with moderate allergic rhinitis (R057). The miR210-3p was already known to be one of the markers in cell cycle regulation, cell survival, differentiation, angiogenesis, as well as in metabolism [43]. The miR-210-3p is upregulated in most solid tumors, and its levels correlate with a negative clinical outcome [44]. The miR-210 is a marker associated with bone [45]. More interestingly, it is a marker associated with nerve [46]. Since the difference and early acknowledge of arthritis between the PSA and the PSO patients could be patient awareness of pain, we decided to look into the miR210-3p in this preliminary research.

By combining the retrospective chart review and the prospective research results, we demonstrated in this research that the PSA patients could have either simple or complex clinical manifestations, including allergic rhinitis, gout, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome.

The search for useful clinical markers for distinguishing between PSO and PSA has been tedious. So, we ultimately turned into the microRNA chip to screen for potential serology markers to distinguish PSA from PSO. As a result, plasma hs-miR210-3p was found to be a marker that distinguishes patients with PSO from patients with PSA, as it changes significantly in Ct levels (p = 0.04). After treatment with biologics agents, the Ct level of hs-miR210-3p gradually increased and reached the average Ct levels of hs-miR210-3p as in PSO patients. The change between PSA patients and PSA patients after biologic treatment differed greatly (p = 0.04), which indicates that PSA patients’ hs-miR210-3p was restored after treatment (Fig. 2; Table 3).

This preliminary proof-of-concept research combined a retrospective chart review study and a prospective microRNA study. Still, the study has several limitations. First, some data were missing, and no longitudinal data from follow-up examinations were available. Second, steroid doses may have fluctuated in this cross-sectional study; in fact, PSO patients seldom receive steroid treatment. Third, several lifestyle variables and diseases associated with arthritis were not recorded, such as smoking [47], inflammatory bowel disease [48], and alcohol consumption [49,50,51,52], which might be associated with serology markers. Nevertheless, we still have some positive finding that help physicians to make early diagnosis of PSA among psoriasis patients by looking for comorbidities with gout, hyperlipidemia, inflammatory back pain, and allergic rhinitis. Moreover, miR-210-3p could be a marker that differentiates between PSO and PSA and also between before and after biologics treatment.

Conclusions

Clinicians should be particularly aware of such manifestations as gout, hyperlipidemia, axial spondylopathy (inflammatory back pain), and allergic rhinitis in PSO in order to ensure the early diagnosis of PSA among psoriasis patients. Moreover, miR-210-3p could be a marker that differentiates between PSO and PSA and also between before and after biologics treatment.

Data availability

All of the underlying research material related to our article can be accessed on demand by e-mail notification.

References

Anandarajah AP, Ritchlin CT (2009) The diagnosis and treatment of early psoriatic arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 5(11):634–641. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2009.210

Eder L, Jayakar J, Thavaneswaran A, Haddad A, Chandran V, Salonen D, Rosen CF, Gladman DD (2014) Is the MAdrid Sonographic Enthesitis Index useful for differentiating psoriatic arthritis from psoriasis alone and healthy controls? J Rheumatol 41(3):466–472. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.130949

Gulliver W, Lynde C, Dutz JP, Vender RB, Yeung J, Bourcier M, Dion PL, Hong CH, Searles G, Poulin Y (2015) Think beyond the skin: 2014 Canadian expert opinion paper on treating to target in plaque psoriasis. J Cutan Med Surg 19(1):22–27. https://doi.org/10.2310/7750.2014.13151

Smolen JS, Braun J, Dougados M, Emery P, Fitzgerald O, Helliwell P, Kavanaugh A, Kvien TK, Landewe R, Luger T, Mease P, Olivieri I, Reveille J, Ritchlin C, Rudwaleit M, Schoels M, Sieper J, Wit M, Baraliakos X, Betteridge N, Burgos-Vargas R, Collantes-Estevez E, Deodhar A, Elewaut D, Gossec L, Jongkees M, Maccarone M, Redlich K, van den Bosch F, Wei JC, Winthrop K, van der Heijde D (2014) Treating spondyloarthritis, including ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis, to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis 73(1):6–16. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203419

Schoels MM, Braun J, Dougados M, Emery P, Fitzgerald O, Kavanaugh A, Kvien TK, Landewe R, Luger T, Mease P, Olivieri I, Reveille J, Ritchlin C, Rudwaleit M, Sieper J, Smolen JS, Wit M, van der Heijde D (2014) Treating axial and peripheral spondyloarthritis, including psoriatic arthritis, to target: results of a systematic literature search to support an international treat-to-target recommendation in spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 73(1):238–242. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203860

Maldonado Ficco H, Citera G, Maldonado Cocco JA (2014) Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in psoriasis patients according to newer classification criteria. Clin Rheumatol 33(2):243–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-013-2412-2

Alexandroff AB, Pauriah M, Camp RD, Lang CC, Struthers AD, Armstrong DJ (2009) More than skin deep: atherosclerosis as a systemic manifestation of psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 161(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09281.x

Dalmady S, Kiss M, Kepiro L, Kovacs L, Sonkodi G, Kemeny L, Gyulai R (2013) Higher levels of autoantibodies targeting mutated citrullinated vimentin in patients with psoriatic arthritis than in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Clin Dev Immunol 2013:474028–474029. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/474028

Mosterd K, Kapinga TH, Martens H, van Mierlo PL, Schoonbrood TH, Poblete-Gutierrez P (2011) Psoriasiform disorders with joint symptoms. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 155(30–31):A2636

Wei SS, Sinniah R (2013) Adalimumab (TNF alpha inhibitor) therapy exacerbates IgA glomerulonephritis acute renal injury and induces lupus autoantibodies in a psoriasis patient. Case Rep Nephrol 2013:812781–812784. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/812781

Rose S, Sheth NH, Baker JF, Ogdie A, Raper A, Saboury B, Werner TJ, Thomas P, Vanvoorhees A, Alavi A, Torigian DA, Gelfand JM, Mehta NN (2013) A comparison of vascular inflammation in psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and healthy subjects by FDG-PET/CT: a pilot study. Am J Cardiovasc Dis 3(4):273–278

Kremers HM, McEvoy MT, Dann FJ, Gabriel SE (2007) Heart disease in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 57(2):347–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2007.02.007

Patel RV, Clark LN, Lebwohl M, Weinberg JM (2009) Treatments for psoriasis and the risk of malignancy. J Am Acad Dermatol 60(6):1001–1017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2008.12.031

Tsai TF, Wang TS, Hung ST, Tsai PI, Schenkel B, Zhang M, Tang CH (2011) Epidemiology and comorbidities of psoriasis patients in a national database in Taiwan. J Dermatol Sci 63(1):40–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdermsci.2011.03.002

Sehgal S, Kumar B, Kaur S, Datta U, Anand S (1988) Antibodies to extractable nuclear antigens in psoriasis vulgaris. Indian J Med Res 87:270–274

Nguyen CM, Liao W (2015) Genomic imprinting in psoriasis and atopic dermatitis: a review. J Dermatol Sci 80:89–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdermsci.2015.08.004

Frankl J, Koranyi B (1950) Psoriasis and pyoderma. Z Haut Geschlechtskr 8(9):342–347

Barker LP (1953) Case for diagnosis: pyoderma; onychomycosis; psoriasis. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol 68(2):233–234

Schwandt A, Bergis D, Dapp A, Ebner S, Jehle PM, Koppen S, Risse A, Zimny S, Holl RW (2015) Psoriasis and diabetes: a multicenter study in 222078 type 2 diabetes patients reveals high levels of depression. J Diabetes Res 2015:792968–792910. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/792968

Lee MS, Lin RY, Lai MS (2014) Increased risk of diabetes mellitus in relation to the severity of psoriasis, concomitant medication, and comorbidity: a nationwide population-based cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol 70(4):691–698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.023

Qureshi AA, Choi HK, Setty AR, Curhan GC (2009) Psoriasis and the risk of diabetes and hypertension: a prospective study of US female nurses. Arch Dermatol 145(4):379–382. https://doi.org/10.1001/archdermatol.2009.48

Verna EC, Loomba R (2015) Editorial: call to screen for NAFLD and NASH in psoriasis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 41(5):492–493. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.13075

Roberts KK, Cochet AE, Lamb PB, Brown PJ, Battafarano DF, Brunt EM, Harrison SA (2015) The prevalence of NAFLD and NASH among patients with psoriasis in a tertiary care dermatology and rheumatology clinic. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 41(3):293–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.13042

Merola JF, Wu S, Han J, Choi HK, Qureshi AA (2015) Psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and risk of gout in US men and women. Ann Rheum Dis 74(8):1495–1500. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205212

Morasiewicz P, Koprowski P, Dragan S (2014) Coexisting psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, gout and Dupuytren’s contracture. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil 16(4):441–447. https://doi.org/10.5604/15093492.1119622

Machado P, Landewe R, Braun J, Baraliakos X, Hermann KG, Hsu B, Baker D, van der Heijde D (2013) Ankylosing spondylitis patients with and without psoriasis do not differ in disease phenotype. Ann Rheum Dis 72(6):1104–1107. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202922

Taha EA, Mekky MA, Morsy H, Saleh MA, Nafeh HM, Ez-Aldin AM, Sayed SK (2014) Study of the impact of viral load of hepatitis C on patients with concomitant psoriasis vulgaris. Arab J Gastroenterol 15(3–4):98–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajg.2014.08.001

Brazzelli V, Carugno A, Alborghetti A, Cananzi R, Sangiovanni L, Barbarini G, De Silvestri A, Borroni RG (2012) Hepatitis C infection in Italian psoriatic patients: prevalence and correlation with patient age and psoriasis severity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 26(12):1581–1582. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04360.x

Weber JA, Baxter DH, Zhang S, Huang DY, Huang KH, Lee MJ, Galas DJ, Wang K (2010) The microRNA spectrum in 12 body fluids. Clin Chem 56(11):1733–1741. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2010.147405

Haroon M, Gallagher P, FitzGerald O (2015) Diagnostic delay of more than 6 months contributes to poor radiographic and functional outcome in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 74(6):1045–1050. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204858

Spelman L, Su JC, Fernandez-Penas P, Varigos GA, Cooper AJ, Baker CS, Lee M, Ring JM, Thirunavukkarasu K (2015) Frequency of undiagnosed psoriatic arthritis among psoriasis patients in Australian dermatology practice. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 29:2184–2191. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.13210

Nas K, Karkucak M, Durmus B, Karatay S, Capkin E, Kaya A, Ucmak D, Akar ZA, Cevik R, Kilic E, Kilic G, Ozgocmen S (2015) Comorbidities in patients with psoriatic arthritis: a comparison with rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. Int J Rheum Dis 18:873–879. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185X.12580

Raychaudhuri SP (2012) Comorbidities of psoriatic arthritis -- metabolic syndrome and prevention: a report from the GRAPPA 2010 annual meeting. J Rheumatol 39(2):437–440. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.111244

Edson-Heredia E, Zhu B, Lefevre C, Wang M, Barrett A, Bushe CJ, Cox A, Wu JJ, Maeda-Chubachi T (2015) Prevalence and incidence rates of cardiovascular, autoimmune, and other diseases in patients with psoriatic or psoriatic arthritis: a retrospective study using Clinical Practice Research Datalink. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 29(5):955–963. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.12742

Candia R, Ruiz A, Torres-Robles R, Chavez-Tapia N, Mendez-Sanchez N, Arrese M (2015) Risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 29(4):656–662. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.12847

Ito M, Ogawa K, Takeuchi K, Nakada A, Heishi M, Suto H, Mitsuishi K, Sugita Y, Ogawa H, Ra C (2004) Gene expression of enzymes for tryptophan degradation pathway is upregulated in the skin lesions of patients with atopic dermatitis or psoriasis. J Dermatol Sci 36(3):157–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdermsci.2004.08.012

Ciccia F, Guggino G, Ferrante A, Raimondo S, Bignone R, Rodolico V, Peralta S, Van Tok M, Cannizzaro A, Schinocca C, Ruscitti P, Cipriani P, Giacomelli R, Alessandro R, Dieli F, Rizzo A, Baeten D, Triolo G (2016) IL-9 over-expression and Th9 polarization characterize the inflamed gut, the synovial tissue and the peripheral blood of patients with psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 68:1922–1931. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.39649

Micosse C, von Meyenn L, Steck O, Kipfer E, Adam C, Simillion C, Seyed Jafari SM, Olah P, Yawlkar N, Simon D, Borradori L, Kuchen S, Yerly D, Homey B, Conrad C, Snijder B, Schmidt M, Schlapbach C (2019) Human "TH9" cells are a subpopulation of PPAR-gamma(+) TH2 cells. Sci Immunol 4(31):eaat5943. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciimmunol.aat5943

Li T, Rong HM, Zhang C, Zhai K, Tong ZH (2018) IL-9 deficiency promotes pulmonary Th17 response in murine model of pneumocystis infection. Front Immunol 9:1118. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.01118

Fort MM, Cheung J, Yen D, Li J, Zurawski SM, Lo S, Menon S, Clifford T, Hunte B, Lesley R, Muchamuel T, Hurst SD, Zurawski G, Leach MW, Gorman DM, Rennick DM (2001) IL-25 induces IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 and Th2-associated pathologies in vivo. Immunity 15(6):985–995

Chiu YG, Shao T, Feng C, Mensah KA, Thullen M, Schwarz EM, Ritchlin CT (2010) CD16 (FcRgammaIII) as a potential marker of osteoclast precursors in psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 12(1):R14. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar2915

Chiu YH, Ritchlin CT (2012) Biomarkers to diagnose early arthritis in patients with psoriasis. Psoriasis Forum / National Psoriasis Foundation 18(2):2–10

Bavelloni A, Ramazzotti G, Poli A, Piazzi M, Focaccia E, Blalock W, Faenza I (2017) MiRNA-210: a current overview. Anticancer Res 37(12):6511–6521. https://doi.org/10.21873/anticanres.12107

Dias F, Teixeira AL, Ferreira M, Adem B, Bastos N, Vieira J, Fernandes M, Sequeira MI, Mauricio J, Lobo F, Morais A, Oliveira J, Kok K, Medeiros R (2017) Plasmatic miR-210, miR-221 and miR-1233 profile: potential liquid biopsies candidates for renal cell carcinoma. Oncotarget 8(61):103315–103326. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.21733

Gu H, Wu L, Chen H, Huang Z, Xu J, Zhou K, Zhang Y, Chen J, Xia J, Yin X (2019) Identification of differentially expressed microRNAs in the bone marrow of osteoporosis patients. Am J Transl Res 11(5):2940–2954

Jiang Y, Li L, Tan X, Liu B, Zhang Y, Li C (2015) miR-210 mediates vagus nerve stimulation-induced antioxidant stress and anti-apoptosis reactions following cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. J Neurochem 134(1):173–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnc.13097

Jaramillo JD, Wilson C, Stinson DJ, Lynch DA, Bowler RP, Lutz S, Bon JM, Arnold B, McDonald ML, Washko GR, Wan ES, DeMeo DL, Foreman MG, Soler X, Lindsay SE, Lane NE, Genant HK, Silverman EK, Hokanson JE, Make BJ, Crapo JD, Regan EA (2015) Reduced bone density and vertebral fractures in smokers. Men and COPD patients at increased risk. Ann Am Thorac Soc 12(5):648–656. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201412-591OC

Wada Y, Hisamatsu T, Naganuma M, Matsuoka K, Okamoto S, Inoue N, Yajima T, Kouyama K, Iwao Y, Ogata H, Hibi T, Abe T, Kanai T (2015) Risk factors for decreased bone mineral density in inflammatory bowel disease: a cross-sectional study. Clin Nutr 34:1202–1209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2015.01.003

Farber EM, Nall L (1994) Psoriasis and alcoholism. Cutis 53(1):21–27

Marrakchi S, Kim I, Delaporte E, Briand G, Degand P, Maibach HI, Thomas P (1994) Vitamin A and E blood levels in erythrodermic and pustular psoriasis associated with chronic alcoholism. Acta Derm Venereol 74(4):298–301

Widmer A (1995) A case from practice (337). Psoriasis vulgaris, Hallopeau’s continuous suppurative acrodermatitis. Psoriatic arthropathy. Chronic alcoholism with personality changes, polyneuropathy, hepatopathy. Cardiomyopathy with chronic atrial fibrillation, thrombocytopathy, macrocytosis. Praxis 84(48):1435

Dediol I, Buljan M, Buljan D, Bulat V, Zivkovic MV, Situm M (2009) Association of psoriasis and alcoholism: psychodermatological issue. Psychiatr Danub 21(1):9–13

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Dr. Eric Yang and Dr. Jason Chuang for their technical support and their help in analyzing the circulating microRNA.

Funding

This study was supported by Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital for grant funding CMRPG8G0272, NMRPG8G6182, and MOST-106-2314-B-182A-156-MY3.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YJS participated in the design of the study and drafted the manuscript. He conducted the sequence alignment and clinical evaluation of patients and participated in its design and coordination, and he drafted the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by Chang Gung Memorial Hospital’s Institutional Review Committee on Human Research (Institutional Review Board numbers: 102-4669B and 104-5733B). Informed consent was not obtained from the individual patients in the retrospective part of study.

Consent to publish

The author read and approved the final manuscript and agrees to publish.

Disclosures

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 15 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Su, YJ. Early diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis among psoriasis patients: clinical experience sharing. Clin Rheumatol 39, 3677–3684 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-05132-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-05132-1