Abstract

Background

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a challenging heterogeneous disease. The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) and the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and PsA (GRAPPA) last published their respective recommendations for the management of PsA in 2015. However, these guidelines are primarily based on studies conducted in resource replete countries and may not be applicable in countries in the Americas (except Canada and USA) and Africa. We sought to adapt the existing recommendations for these regions under the auspices of the International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR).

Process

The ADAPTE Collaboration (2009) process for guideline adaptation was followed to adapt the EULAR and GRAPPA PsA treatment recommendations for the Americas and Africa. The process was conducted in three recommended phases: set-up phase; adaptation phase (defining health questions, assessing source recommendations, drafting report), and finalization phase (external review, aftercare planning, and final production).

Result

ILAR recommendations have been derived principally by adapting the GRAPPA recommendations, additionally, EULAR recommendations where appropriate and supplemented by expert opinion and literature from these regions. A paucity of data relevant to resource-poor settings was found in PsA management literature.

Conclusion

The ILAR Treatment Recommendations for PsA intends to serve as reference for the management of PsA in the Americas and Africa. This paper illustrates the experience of an international working group in adapting existing recommendations to a resource-poor setting. It highlights the need to conduct research on the management of PsA in these regions as data are currently lacking.

Key Points • The paper presents adapted recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis in resource-poor settings. • The ADAPTE process was used to adapt existing GRAPPA and EULAR recommendations by collaboration with practicing clinicians from the Americas and Africa. • The evidence from resource-poor settings to answer clinically relevant questions was scant or non-existent; hence, a research agenda is proposed. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a spondyloarthritis that affects up to a third of patients with psoriasis, a common inflammatory skin disease affecting 1–3% of the population [2]. The heterogeneous disease manifestations make management of PsA a challenge [3]. The Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) have updated their respective recommendations [4, 5] for the management of PsA. These recommendations are based on systematic reviews of literature and provide evidence-based recommendations for the management of PsA. However, they are primarily based on studies conducted in resource replete countries of Europe and North America; therefore, they may not be applicable to PsA patients in resource-poor countries in the Americas excluding Canada and the USA- (henceforth termed ‘the Americas’) and Africa. To address this gap, our objective was to adapt the published GRAPPA and EULAR recommendations for the management of PsA to resource-poor settings using the ADAPTE process [6].

Methods and results

Under the auspices of the International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR), we aimed to create recommendations for the management of PsA in resource-poor settings. The recommendations were targeted at clinicians caring for PsA patients more than 16 years of age residing in the Americas or Africa. The target audience for these recommendations includes rheumatologists, dermatologists, internists, primary care practitioners, patients and other stakeholders practicing or living in the Americas or Africa. The Asia-Pacific region was not included since the Asia Pacific League of Associations for Rheumatology (APLAR) is also developing similar recommendations.

ADAPTE process

Assembly of the organizing committee

An organizing committee of 8 rheumatologists with experience in PsA treatment recommendations and/or practice in resource-poor settings was established. The committee consisted of rheumatology experts, researchers, and active GRAPPA members. The committee decided to use the ADAPTE process to develop the new recommendations. The ADAPTE Collaboration [1] defines guideline adaptation as the systematic approach to considering the use and/or modification of (a) guideline(s) produced in one cultural and organizational setting for application in a different context. The process includes three phases: set-up phase, adaptation phase, and finalization phase.

Phase one: set-up

Panel of participants

One hundred and thirty-four potential participants (rheumatologists and dermatologist, GRAPPA and some non-GRAPPA members of the Panamerican League of Associations for Rheumatology (PANLAR), the African League Against Rheumatism (AFLAR), and Asia-Pacific League of Associations for Rheumatology (APLAR) regions) were invited by the organizing committee to participate in an initial email survey. Members from the APLAR region were invited to provide input since they had experience in treating PsA in similar resource-poor settings. The objectives were to identify specific challenges in their local practice particularly access to specialists, access to therapies, infectious diseases, and any specific comorbidities that may influence management of PsA.

Seventy-nine respondents (57 rheumatologists and 22 dermatologists) completed the survey, of whom 16 were from Africa and 46 were from the Americas. Respondents were invited to be members of the recommendation panel. Thirty-six participants provided an affirmative response, but only 15 participants completed the project (10 rheumatologists and 5 dermatologists). The entire task force of this project represented five countries in the Americas, four countries in Africa, and four countries from other regions.

Based on the responses and a face-to-face meeting held at the annual GRAPPA meeting in 2017, the committee and the panel members identified three areas of interest to be included in the adapted recommendations: (a) efficacy and safety of pharmacotherapy, (b) recommendations for physicians with limited access to other specialists, (c) screening and management of tuberculosis (TB), hepatitis B/C virus infection (HB/CV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease, Chagas’ disease, leishmaniasis, and leprosy. Subsequently, members selected their area(s) of interest to work on; thus, three working groups were formed.

Phase two: adaptation

Determining the health questions

After having identified the areas of interest, members of the committee drafted the PIPOH criteria and the health questions which was used as a tool (Table 1):

P Patient population (including disease characteristics)

I Intervention of interest

P Professionals/patients (audience for whom the guideline is prepared)

O Outcomes to be taken into consideration (purpose of the guideline)

H Healthcare setting and context

The drafted PIPOH criteria and the health questions were disseminated via email to the entire task force for refinement. Three Patient Research Partners from the Americas also participated in this task. The PIPOH criteria and 18 questions developed are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Screening source recommendations

The source recommendations were assessed on their clinical content according to the health questions formulated. We modified the ADAPTE tool 8: Table for Summarizing Guideline Content to prepare a table in which participants of each working group were asked whether an answer was stated in the source recommendations and their degree of agreement with that answer if available. After an iterative process, ten questions reached < 70% of agreement. To answer these questions, a systematic review of literature from the Americas and Africa was conducted.

Search for other documents: systematic literature review

The systematic search included the following databases: Medline, Embase, African Index Medicus (AIM), Cochrane Central, and Literatura Latino Americana en Ciencias de la Salud (Latin-American Literature in Health Science- LILACS); and literature identified by the panel of participants. Inclusion criteria were: (1) Randomized controlled trials, (2) observational studies, (3) case series, (4) resource-poor settings in the Americas or Africa, and (5) any language. Exclusion criteria were: (1) review articles, (2) abstracts, (3) conference proceedings, (4) case report.

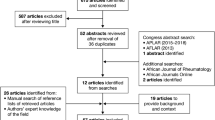

A systematic review to update the source recommendations was not performed since it would have been outside the scope of our objective. After duplicates were removed, articles were selected through a screening process based first on the title, second on abstract and third on the full-text review (Fig. 1). Articles were retrieved if their content was relevant to the health questions framed by the PIPOH definition for this project. Three authors carried out the data extraction independently.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram, record identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion. The search terms included PsA, the Americas, Africa, and infectious diseases. Studies included from database inception until February 22 2018 well as literature sent by the panel. The search strategy and MESH terms are provided in Appendix 1

The search identified 8135 articles. Of these, 24 were identified for full review and data extraction (Fig. 1). Despite this exhaustive systematic literature review (SLR), there were several health questions for this project that were not addressed by evidence retrieved. These included questions related to the safety of combinations of conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (csDMARDs) and biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) in general and in areas with endemic infections, the frequency of monitoring of individuals on therapy in resource-poor settings and recommendations for dermatologists treating PsA without rheumatology support or vice versa.

Given the availability and use of biosimilar and intended copies, our search also included studies on the use of this group of drugs in PsA. One review article addressed this topic but unfortunately did not offer a clear conclusion due to a lack of evidence. When investigating the safety screening required for csDMARD or bDMARD therapy in PsA, nine studies were identified that reported screening for infectious diseases. None of these studies were reported exclusively in PsA patients and none were RCTs. The majority looked into TB screening (n = 8) and showed that tuberculin skin test and chest radiographs are widely used as screening tests, but the best method is still debated particularly in endemic areas.

Concerning the use of bDMARDs, 14 studies were identified that examined bDMARD use on patients in the Americas or Africa. These studies identified successful use of bDMARDs in areas of endemic infection, but limited data included meant that no recommendations different from the current ones could be made. Studies around treatment of comorbidities in PsA did not identify specific literature from the Americas or Africa.

Assessment of guideline quality

The quality of the GRAPPA and EULAR source recommendations was evaluated with the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) Instrument [7] (available at http://www.agreetrust.org/). AGREE II Instrument evaluates the process of practice guideline development and the quality of reporting by using the AGREE Reporting Checklist [8]. This instrument includes 23 items that are organized into six domains: 1. scope and purpose; 2. stakeholder involvement; 3. rigor of development; 4. clarity of presentation; 5. applicability; and 6. editorial independence. Each of the 23 items targets various aspects of practice guideline quality. Each item is scored on a scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”). Each source recommendation was independently assessed by two reviewers who upon the completion of those 23 items also provided 2 additional overall assessments of the guideline: the overall quality of the recommendation scored again from 1 to 7 and a recommendation about its use by selecting the ‘Yes’ or ‘Yes with modifications’ or ‘No’ options provided. We used the raw AGREE scores to determine agreement amongst the appraisers on various items of the AGREE domains (Fig. 2).

GRAPPA treatment schema, recommendations for each domain. ©2016, American College of Rheumatology. With permission from John Wiley and Sons. GRA PPA treatment schema for active psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Light text identifies conditional recommendations for drugs that do not currently have regulatory approvals or for which recommendations are based on abstract data only. CS corticosteroid, vit vitamin, CSA cyclosporine A, DMARDs disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, IA intraarticular, IL-12/23i interleukin-12/23 inhibitor, LEF leflunomide, MTX methotrexate, NSAIDs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, PDE-4i phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor (apremilast), phototx phototherapy, SpA spondyloarthritis, SSZ sulfasalazine, TNFi tumor necrosis factor inhibitor

Assess applicability

The applicability of the principles contained in the source recommendations was assessed using Tool 15-Evaluation Sheet-Acceptability/Applicability. According to ADAPTE’s definition of acceptability and applicability, “Acceptable” indicates that it should be put it into practice, and ‘Applicable’ indicates that physicians are able to put it into practice. A table was sent to the committee members to assess the acceptability of each principle in terms of our target population, benefits to this population, and its compatibility with the culture and values of the population, and to assess the applicability of each principle in terms of availability of the intervention, expertise, legal and resource constraints. They were provided with three options: Accept as is, modify, or reject principle for further discussion (for an example see Appendix 2).

Principles from both source guidelines with a score of more than 80% in the “accept as is” option of the acceptability and applicability items were taken as overarching principles for the adapted ILAR recommendations.

Adaptation of the principles and the recommendations

GRAPPA and EULAR PsA treatment recommendations are recent guidelines with strong methodological quality from where principles and recommendations were adapted to produce ILAR PsA treatment recommendations for resource-poor countries. Members of the organizing committee summarized principles and recommendations from the source recommendations, and the supporting evidence of the SLR to address each health question and their applicability to the context of use according to the assessments previously described.

Principles

The principles are shown in Table 3. Those were selected according to their acceptability and applicability with an agreement of more than 80%.

Recommendations

Recommendations are shown in Table 4. Those were selected if their clinical content provided answers to the health questions formulated and if they reached a consensus of more than 70%. Where available, data from the literature search was used for unanswered health questions. However due to a lack of data, expert opinion was sought for the answers not found in the SLR. Although specific data were not found relating to treatment in the presence of comorbidities, this was felt to be important in all healthcare settings. Thus, the comorbidities table highlighting potential risks and benefits to comorbidities with different therapies taken from the GRAPPA recommendations was included (Table 5).

Phase three: finalization

External review and acknowledgment

After the recommendations were adapted the document was sent for external review to a dermatologist from the Americas and a rheumatologist from Africa for review. Feedback was solicited using the ADAPTE feedback questionnaire and free text. Overall the recommendations were supported and found to be beneficial. Given the inclusion of targeted therapies in the management of PsA, one reviewer felt that the recommendations were too expensive to apply given poor access to these drugs in some settings. They highlighted a relative lack of data to support the process and suggested a research agenda to be included within this recommendation (Table 6).

Approval by endorsing bodies

These recommendations are adapted from the GRAPPA and EULAR published recommendations and we acknowledge these source documents [4, 5]. Following development of this manuscript, source guideline developers were consulted for feedback.

Plan for review and update

The management of PsA is a rapidly evolving field with a number of new medications approved since the 2015 recommendations and further drugs currently in development. As EULAR and GRAPPA update their recommendations, these recommendations should also undergo periodic update.

Discussion

The Institute of Medicine defines clinical guidelines as “systematically developed statements to assist practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances [9]. Hence, we aimed to adapt the most recently published GRAPPA and EULAR recommendations for the management of PsA for resource-poor settings. We followed the ADAPTE process and formulated PIPOH questions and conducted a systematic review of literature addressing these questions where it was not addressed by the source recommendations. However, evidence from the literature to answer the questions was weak or non-existent forcing us to resort to expert opinion. A research agenda in order to spur research into gaps in knowledge about management of PsA in resource-poor settings was formulated.

This process used published treatment recommendations for PsA, a heterogeneous disease affecting the skin and musculoskeletal structures, which have been developed and revised by GRAPPA [4] and EULAR [5], and most recently by the American College of Rheumatology [10]. However, these recommendations were developed based on data obtained largely in resource-replete settings and are more easily applicable to advanced economies. The applicability of these recommendations to resource-poor settings is questionable.

We chose to use the ADAPTE process and adapt existing recommendations rather than develop new recommendations. We believed that developing new recommendations from available literature would not be efficient since the current recommendations are based on review of recent developments in the field and are unlikely to be significantly different. We, therefore, chose to review the literature from the Americas and Africa to address questions relevant to management of PsA in resource-poor settings. Unfortunately, there is very little research done in resource-poor settings to address important practical questions about the management of PsA in the Americas and Africa.

We were able to engage rheumatologists and dermatologists as well as patients in developing these recommendations. The PIPOH questions were developed mainly by practitioners and patients from the Americas and Africa and their input was crucial in providing expert opinion for the adapted recommendations. The strong collaborative effort across continents sets the stage for designing studies to address unmet needs using the research network we have developed through this exercise.

The recommendations demonstrate that the goals of treatment, assessment of disease and associated comorbidities, and principles of safety and follow up are similar to the source recommendations. However, the type and severity of comorbidities are likely to be different in resource-poor settings. It is believed that the burden of concomitant infectious diseases such as TB, HB/CV, HIV, Chagas’ disease, and leishmaniasis is likely to be higher although high-quality studies showing high prevalence in PsA were lacking. Given the likelihood of adverse outcomes with newer immunomodulatory therapy, studies evaluating the safety and efficacy of these drugs in resource-poor settings are required but are currently lacking (and/or) are of poor quality. Pragmatic interventional and observational trials with the newer agents in resource-poor settings will benefit clinical decision-making and are on the research agenda.

Likewise, the prevalence of chronic disease is also rising in resource-poor settings [11]. Thus the management of PsA and associated non-communicable as well as infection-related comorbidities is challenging and will need to be addressed in future research studies given the lack of literature. We have provided expert opinion and acknowledge its inherent limitations.

One major unanswered question in the management of PsA is the safety and efficacy of combination therapy. Combination therapy (with multiple csDMARDs or a combination of csDMARDS and bDMARDs) is often used by clinicians in resource-replete as well as resource-poor settings but the evidence for efficacy and safety (especially with comorbidities) is lacking. Similarly, biosimilars and intended copies are increasingly available and being used with limited evidence about its safety and efficacy in patients with PsA. This is particularly relevant in the resource-poor setting where access to costly newer medications is poor and hence combination therapy or use of intended copies is likely to be more frequent in PsA resistant to monotherapy. Further research in this area is of utmost importance. One related clinical question is also how frequently to monitor patients. This is primarily a question of resources since the doctor-patient ratio and the resources for conducting laboratory tests are grossly inadequate in most countries. An efficient and cost-effective model is required but is yet to be developed. Moreover, educational programs to guide rheumatologists in the management of psoriasis when access to a dermatologist is poor, and to a dermatologist for the management of PsA when access to a rheumatologist or internist is difficult may improve care of PsA in these settings.

We did not include studies from the Asia-Pacific region in this exercise since APLAR was developing their own recommendations. However, we intend to collaborate with researchers and clinicians from that region to develop country or region-specific recommendations and share best practices. Moreover, we did not include the most recent American College of Rheumatology/National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines for the treatment of PsA [10] or the most recent update of the EULAR PsA treatment recommendations since these recommendations were published only after our literature review and guideline appraisals were completed.

Thus, the ILAR Treatment Recommendations for PsA were developed through the collaborative effort of researchers and clinicians from the Americas including Canada, Africa, and the UK. These recommendations intend to serve as reference for the management of PsA in resource-poor settings in the Americas and Africa. This paper illustrates the experience of an international working group in adapting existing recommendations to resource-poor setting. It highlights the need to conduct research on the management of PsA in these regions, sets a research agenda and intends to form the basis to conduct collaborative clinical research on the management of PsA in resource-poor settings.

References

The ADAPTE Collaboration (2009) The ADAPTE process: resource toolkit for guideline adaptation, Version 2.0. Available from: http://www.g-i-n.net. Direct access to the Guideline Adaptation: A Resource Toolkit https://www.g-i-n.net/document-store/working-groups-documents/adaptation/adapte-resource-toolkit-guideline-adaptation-2-0.pdf

Mease PJ, Gladman DD, Papp KA, Khraishi MM, Thaçi D, Behrens F, Northington R, Fuiman J, Bananis E, Boggs R, Alvarez D (2013) Prevalence of rheumatologist-diagnosed psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis in European/North American dermatology clinics. J Am Acad Dermatol 69(5):729–735

Ritchlin CT, Colbert RA, Gladman DD (2017) Psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med 376(10):957–970

Coates LC, Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ et al (2016) Group for research and assessment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis 2015 treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 68(5):1060–1071

Gossec L, Smolen JS, Ramiro S et al (2016) European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies: 2015 update. Ann Rheum Dis 75(3):499–510

Fervers B, Burgers JS, Voellinger R, Brouwers M, Browman GP, Graham ID, Harrison MB, Latreille J, Mlika-Cabane N, Paquet L, Zitzelsberger L, Burnand B, ADAPTE Collaboration (2011) Guideline adaptation: an approach to enhance efficiency in guideline development and improve utilisation. BMJ Qual Saf 20(3):228–236

AGREE II: Brouwers M, Kho ME, Browman GP, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Hanna S, Makarski J on behalf of the AGREE next steps consortium (2010) AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in healthcare. Can Med Assoc J 182:E839–842 https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.090449

AGREE Reporting Checklist: Brouwers MC, Kerkvliet K, Spithoff K, AGREE Next Steps Consortium (2016) The AGREE Reporting Checklist: a tool to improve reporting of clinical practice guidelines. BMJ 352:i1152 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i1152

Field MJ, Lohr KN (eds) (1990) Clinical practice guidelines: directions for a new program. National Academy Press, Washington, DC

Singh JA, Guyatt G, Ogdie A, Gladman DD, Deal C, Deodhar A, Dubreuil M, DunhamJ HME, Kenny S, Kwan-Morley J, Lin J, Marchetta P, Mease PJ, Merola JF, Miner J, Ritchlin CT, Siaton B, Smith BJ, Van Voorhees AS, Jonsson AH, Shah AA, Sullivan N, Turgunbaev M, Coates LC, Gottlieb A, Magrey M, Nowell WB, Orbai AM, Reddy SM, Scher JU, Siegel E, Siegel M, Walsh JA, Turner AS, Reston J (2019) Special Article: 2018 American College of Rheumatology/National Psoriasis Foundation Guideline for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 71(1):5–32

Arokiasamy P, Uttamacharya KP, Capistrant BD, Gildner TE, Thiele E, Biritwum RB, Yawson AE, Mensah G, Maximova T, Wu F, Guo Y, Zheng Y, Kalula SZ, Salinas Rodríguez A, Manrique Espinoza B, Liebert MA, Eick G, Sterner KN, BarrettTM DK, Gonzales E, Ng N, Negin J, Jiang Y, Byles J, Madurai SL, Minicuci N, Snodgrass JJ, Naidoo N, Chatterji S (2017) Chronic noncommunicable diseases in 6 low-and middle-income countries: findings from wave 1 of the World Health Organization’s Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE). Am J Epidemiol 185(6):414–428

Funding

The process of developing the International League of Associations for Rheumatology Recommendations for the Management of Psoriatic Arthritis in Resource-Poor Settings was funded by the International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The manuscript does not contain clinical studies or patient data.

Conflict of interest

All authors have disclosed any conflicts of interest. The individual declarations are summarized below:

V Chandran reports grants and personal fees from Abbvie, personal fees from Amgen, personal fees from Celgene, personal fees from BMS, personal fees and other from Eli Lilly, personal fees from Janssen, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from UCB, outside the submitted work. L Coates has received research grants from Abbvie, Celgene, Novartis, Pfizer and Lilly, Honoraria from Abbvie, Amgen, Biogen, Celgene, Galapagos, Gilead, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB. GM Mody has received honoraria from Astra Zeneca, GlaxoSmithKline and Janssen.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Previously been published as an abstract:

Citation: Ann Rheum Dis, volume 77, supplement Suppl, year 2018, page A203 DOI: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-eular.5536

ACR Meeting Abstracts - https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/international-league-of-associations-for-rheumatology-systematicreview-of-the-literature-to-inform-treatment-recommendations-for-psoriatic-arthritis-in-resource-poor-countries/

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 62 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elmamoun, M., Eraso, M., Anderson, M. et al. International league of associations for rheumatology recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis in resource-poor settings. Clin Rheumatol 39, 1839–1850 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-04934-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-04934-7