Abstract

The objective of this study is to explore the experiences and attitudes of rheumatologists and oncologists with regard to their patients’ health-related Internet use. In addition, we explored how often physicians referred their patients to health-related Internet sites. We sent a questionnaire to all the rheumatologists and oncologists in the Netherlands. The questionnaire included questions concerning demographics, experiences with patients’ health-related Internet use, referral behavior, and attitudes to the consequences of patients’ health-related Internet use (for patients themselves, the physician-patient relationship and the health care). The response rate was 46% (N = 238). Of these respondents, 134 practiced as a rheumatologist and 104 as an oncologist. Almost all physicians encountered their patients raising information from the Internet during a consultation. They were not, however, confronted with their patients’ health-related Internet use on a daily basis. Physicians had a moderately positive attitude towards the consequences of patients’ health-related Internet use, the physician-patient relationship and the health care. Oncologists were significantly less positive than rheumatologists about the consequences of health-related Internet use. Most of the physicians had never (32%) or only sometimes (42%) referred a patient to a health-related Internet site. Most physicians (53%) found it difficult to stay up-to-date with reliable Internet sites for patients. Physicians are moderately positive about their patients’ health-related Internet use but only seldom refer them to relevant sites. Offering an up-to-date site with accredited websites for patients might help physicians refer their patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

An increasing number of patients are using the Internet to search for health-related information. Reported rates of health-related Internet use by patients with rheumatic disorders vary from 14% to 28% [1–4]. Since mainly younger patients search online for health-related information, it can be expected that in the future this portion of patients will even further increase [1]. A recent study among new rheumatology patients attending rheumatology clinics showed that 62.5% of them searched the Internet to look up their symptoms or suspected condition prior to their first appointment [5].

Patients who use the Internet feel empowered in managing their health, feel more involved in partnerships with their physicians and in making decisions about their treatment [6]. However, Internet use for health-related information has also raised some concerns. Patients may misinterpret information they find on the Internet or they might come across misinformation which can result in a false sense of knowledge and control [7, 8].

Increased Internet use is noticeable in the physicians’ daily practice with patients increasingly broaching health-related information from the Internet [9, 10]. Recently, it is shown, that only 20% of the patients who search for health-related information on the Internet discuss their information with their physicians. The main reason mentioned by patients to not discuss health-related Internet use is the fear of being perceived as challenging their physician [5]. Therefore, it is important to know more about physicians’ attitudes with regard to their patients’ health-related Internet use [5, 11, 12].

The primary purpose of this study was to explore the experiences of rheumatologists and oncologists with their patients’ health-related Internet use and their attitudes towards the consequences thereof (for patients themselves, for the physician-patient relationship and for the health care). We were also interested if and how often physicians referred their patients to health-related Internet sites. In addition, we were interested if the physicians’ age, sex, and profession (rheumatologist or oncologist) are related to their experiences, attitudes, and referral behavior. We chose these two professional groups because of the contrast between the illnesses they treat (chronic disabling versus life threatening).

Methods

Sample and procedure

A questionnaire was mailed to all Dutch rheumatologists and oncologists, followed by one reminder. Of the total of 539 physicians approached (255 rheumatologists and 284 oncologists), 23 (nine rheumatologists and 14 oncologists) were ineligible because they had retired, were no longer in practice, or had no valid address.

Instrument

The items in the questionnaire were derived from literature [e.g., 11, 12] and our earlier research on online peer support groups [e.g., 13, 14]. A draft version of the questionnaire was pre-tested among five medical specialists. Based on their reactions, some textual indistinctness and response options were adapted. The final questionnaire contained questions on the topics written below.

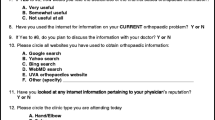

Experiences with patients’ Internet use

The physicians were asked to estimate how many of their patients used the Internet to search for health information. Respondents could choose between the following response options: 0-20%, 21-40%, 41-60%, 61-80%, 81-100%, or ‘I have no idea’. In addition, the physicians were asked how many times during the past month patients had discussed their health-related Internet use with them, and how many times during the past month patients had asked them for referrals to health-related Internet sites. Respondents could answer on a five-point scale that ranged from ‘never’ to ‘almost daily’.

Referral behavior

The physicians were asked how many times during the past month they had referred patients to health-related Internet sites and to online support groups. Respondents could answer on a five-point scale that ranged from ‘never’ to ‘almost daily’. The physicians were also asked how many times during the past month they had visited health-related Internet sites and online support groups. Respondents could answer on a five-point scale that ranged from ‘never’ to ‘almost daily’.

Attitudes towards patients’ Internet use

In total, 20 items were formulated that described the perceived consequences of patients’ health-related Internet use. The items had the format of a statement that began with ‘Patients who use the Internet in relation to their health…’ or ‘Through patients’ seeking health-related information on the Internet…’. Respondents could answer on a five-point scale, that ranged from ‘almost never’ (1) to ‘nearly always’ (5). For each construct, the internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was determined [15]. ‘Consequences for patients’ was measured with seven items (alpha = 0.71). ‘Consequences for the physician-patient relationship’ was measured with seven items (alpha = 0.66). ‘Consequences for the health care’ was measured with six items (alpha = 0.68). For each scale, an average score was computed. Scores could range from 1 ‘negative consequences’ to 5 ‘positive consequences’.

Perceived difficulties with patients’ Internet use

Physicians’ perceived difficulties in coping with their patients’ health-related Internet use were measured with six items. The items had the format of a statement that began with ‘How difficult or how easy is it for you to…’. Respondents could answer on a five-point scale that ranged from ‘very difficult’ (1) to ‘very easy’ (5). The internal consistency for this construct was alpha = 0.77.

Demographic and job characteristics

The respondents were asked to provide information about age, sex, their profession, and the number of years they had been in practice or in training as a medical specialist.

Finally, the respondents were invited to describe by means of a free-text response their positive or negative experiences with their patients’ health-related Internet use.

Data analysis

Differences in continuous variables between rheumatologists and oncologists, male and female physicians and older and younger physicians (split at the median) were tested by means of T tests and differences in categorical variables by chi-square tests. Statistical significance was assumed when alpha <0.05. Free-text responses were used as illustrations for the quantitative data.

Results

The total response rate was 46% (N = 238). Of these respondents, 134 (response rate: 54%) were in practice or in training as a rheumatologist and 104 (response rate: 39%) were in practice or in training as an oncologist. Demographic and job characteristics are reported in Table 1.

Experiences with patients’ Internet use

In total, 80 physicians estimated that 41-60% of their patients sought health-related information on the Internet. A further 58 physicians estimated that 21-40% of their patients used the Internet for health-related reasons; whereas, 51 physicians estimated that 61-80% of their patients did so (data not in table). Almost all physicians experienced patients raising information from the Internet during a consultation (Table 2) but less often that patients asked for referrals to health-related Internet sites. More than half of the physicians (57%) indicated that this never happened.

Female physicians experienced more often than male physicians (p < 0.01) that patients raised information from the Internet during a consultation (data not in table). No relation was found regarding age or profession.

Physicians’ referral behavior

Physicians themselves seldom visited health-related Internet sites and online support groups (Table 2). Most of the physicians had never (32%) or only a couple of times (42%) referred a patient to a health-related Internet site. Most oncologists and rheumatologists had never (69%) or only a couple of times (24%) referred a patient to an online support group. Some of the physicians added in a free-text response that it was not they who referred their patients: “At our center, it is the rheumatology nurse who takes care of the referrals to relevant websites.”

Rheumatologists referred their patients more often to Internet sites than oncologists (p < 0.01). Female physicians referred their patients more often to Internet sites than male physicians (p < 0.05; data not in table). No relation was found regarding age.

Attitudes towards patients’ Internet use

Consequences for patients

The physicians indicated that although patients are often better informed about both their illness (54%) and treatment options (51%) as a result of searching the Internet for health-related information (Table 3), a negative consequence is that patients are more often (32%) or sometimes (53%) unnecessarily concerned. Some of the physicians added in a free-text response that Internet use is only positive for those patients who want to inform themselves after being diagnosed. They were less positive about other goals such as self-diagnosis:

Recently, I saw a woman with fibromyalgia and her partner who didn’t want to accept it. He found information on the Internet stating that the symptoms of FM can be the same as with a vitamin B12 deficiency. They refused to see that a vitamin B12 deficiency was out of the question here. So in this case the information from the Internet was used to prove that it is something other than FM, and that’s when it becomes difficult.

No relation was found regarding sex, age, and profession.

Consequences for the physician-patient relationship

According to the physicians, Internet use by patients can sometimes (48%) or often (30%) lead to patients being more able to participate in the decision making process concerning their treatment (Table 3). The physicians indicated that sometimes (41%) Internet use can even lead to better treatment decisions. Although most of the physicians indicated that patients often (57%) become more assertive as a result of health-related Internet use, they are of the opinion that it rarely has negative consequences for the physician-patient relationship. Most of the physicians indicated that Internet use seldom (46%) or almost never (23%) undermines the physicians’ authority. In addition, the physicians indicated that the bond of confidence between the physicians and the patient is seldom (43%) or almost never (33%) compromised by health-related Internet use. A small majority of the physicians felt that patients raised more unreasonable demands (59%) and that Internet use led to more unnecessary discussion between physicians and patients (51%).

In a free-text response, one physician commented on how the consequences of health-related Internet use for the patient-physician relationship differed between patients: “If the relationship is good, Internet use is not a problem. The biggest problem is with new patients with whom no relationship has yet been forged and who arrive with a certain assertivity or suspicion.”

Oncologists were less positive about the consequences of Internet use for the physician-patient relationship than rheumatologists (p < 0.001). No relation was found regarding sex and age.

Consequences for the health care

The physicians indicated that unnecessary diagnostics and treatments are seldom given as a result of patients’ Internet use (Table 3). Besides indicating that Internet use by patients seldom (36%) or almost never (48%) compromises their reputation, the physicians also commented that the duration of a medical consultation sometimes (39%) or often (36%) increases due to their patients’ Internet use. However, in free-text responses, some of the physicians added that the opposite was also the case: “Using the Internet also yields a shorter duration of the consultation because patients are better informed about their illness and need less explanation.”

Oncologists were less positive about the consequences of Internet use for the health care than rheumatologists (p < 0.01). No relation was found regarding sex and age.

Perceived difficulties in coping with patients’ Internet use

Most physicians indicated that they find it quite easy to deal with their patients’ increasing health-related Internet use (61%), to clear up misunderstandings it caused (59%), and to address the information that patients had found on the Internet (68%; Table 4). Physicians experienced greater difficulties in referring their patients to trustworthy Internet sites or online support groups. Most physicians (53%) found it (very) difficult to stay up to date with reliable health-related Internet sites for patients. One of the physicians illustrated this: “It is imperative that doctors are trained in Internet usage. I rarely know which website to recommend to patients.” Other physicians suggested that an up-to-date list with accredited websites for patients would help them.

Younger physicians (≤46 years) scored significantly lower on the perceived difficulties scale (p < 0.001) than older physicians (data not in table). No relation was found regarding sex or profession.

Discussion

Physicians’ experiences with patients’ health-related Internet use

Physicians are increasingly aware of their patients’ Internet use. The physicians’ estimations corresponded with the degree of health-related Internet use found in our recent study among Dutch patients. This study showed that 42% of the patients with rheumatoid arthritis, 43% of the patients with breast cancer, and 75% of the patients with fibromyalgia had used the Internet to seek health-related information [16]. This is in contrast to Potts and Wyatt [11], who found that physicians in the UK probably underestimate the percentage of patients who used the Internet for health-related reasons. Most of them indicated that only a very small proportion (1-2%) of their patients did so.

Almost all physicians indicated that patients raised information from the Internet during a consultation. This indicates an increase, since Murray et al. [12] found in their 2003 study that only 58% of the physicians had experienced an incident when a patient brought information from the Internet to a consultation. For most of these physicians, this was still a relatively rare event [12]; whereas in our study, we found that over the past month most physicians had been confronted with health-related Internet use regularly. Nevertheless, our study did show that this was still not a daily occurrence.

Physicians’ attitude towards patients’ health-related Internet use

Physicians were moderately positive about the consequences of health-related Internet use for their patients. In the physicians’ opinion, a negative consequence of Internet use is that patients are more often unnecessarily concerned. These results are in line with the findings of a study among patients who participate in online support groups. These patients indicated that they found it stressful to be confronted with the negative sides of their illness in the group, such as metastases or consequential disabilities [14].

The physicians indicated that, in general, the consequence of their patients’ health-related Internet use is also moderately positive for the physician-patient relationship. This is in line with Murray et al. [12] who reported that most physicians indicated that Internet use by patients had a positive (38%) or neutral (54%) effect on the physician-patient relationship. Most Korean rheumatologists were less positive, indicating that health-related Internet use by patients had a neutral (64%) or negative (21%) effect on the physician-patient relationship [2].

Physicians seldom reported negative consequences for the physician-patient relationship. Murray et al. [12] also found that only 17% of the physicians indicated that their authority was challenged by patients who made use of the Internet for health-related reasons. The physicians felt especially challenged when patients tested their knowledge or when patients used the information to diagnose themselves or make their own treatment plan [17]. This feeling of being challenged might also be related to their personal insecurity with regard to using the Internet [18].

Finally, physicians also indicated that they were moderately positive about the consequences of health-related Internet use for the health care in general. Physicians did, however, indicate that the duration of a consultation increases. This is a confirmation of the results of past studies, revealing that physicians considered patients’ health-related Internet use as time consuming [11, 12, 17].

Since our study showed that physicians in general have a moderately positive attitude towards health-related Internet use, patients should not fear to discuss their health-related Internet use during consultations. Discussing health-related information might be of added value because physicians can clarify the information found online and they have the opportunity to adjust information that is misinterpreted by patients. A recent study suggests that discussing health-related information during consultations is related to a higher patient and physician satisfaction [5]. Physicians should therefore consider strategies for enabling communication about health-related Internet use [5].

Physicians’ referral behavior

Physicians seldom referred their patients to health-related Internet sites and online support groups. Although we do see an increase in the physicians’ referral behavior compared to the results of Murray et al. [12], who found that only 35% of the physicians had ever referred patients to websites, it is still not common practice. It is, however, advised that patients be assisted by their physicians in their Internet use for health-related reasons in order for it to be of added value [9, 19–21]. Health professionals need to be able to direct patients to high quality health-related websites [20]. In a study among patients, it was found that 62% of the patients agreed that physicians should recommend websites where patients can learn more about their health care [9]. This is in line with the recommendations made by Gerber and Eiser [19], who introduced the idea of what they called an “Internet prescription”. Physicians should ‘prescribe’ their patients addresses of websites with reliable, evidence-based data.

An explanation for the lack of referrals might be that most of the physicians found it difficult to stay up to date with reliable health-related Internet sites. Some physicians indicated that an up-to-date list with accredited websites for patients would help them with referrals.

Physicians hardly ever visited health-related Internet sites for patients or online patient support groups. This can be seen as a missed opportunity, because one of the benefits of physicians visiting these sites is that they gain increased insight into their patients’ issues. A better understanding might well lead to an improvement of the physician-patient relationship.

Relations found with physicians’ sex, age, and profession

Oncologists were significantly less positive about the consequences of patients’ health-related Internet use for the physician-patient relationship and the health care compared to rheumatologists. This might result from the fact that rheumatologists in general have built a bond of confidence with their patients over many years, in contrast to oncologists who have intensive contact with a patient but for a relatively short period of time. Oncologists referred their patients less often to health-related Internet sites than rheumatologists. However, since cancer is a life-threatening illness, it might even be more important for cancer patients to receive guidance, because for them self-treatment through health-related Internet use has a more destructive consequence.

Female physicians indicated significantly more often that their patients raised information from the Internet during a consultation. This might result from the fact that female physicians tend to show more affiliative behavior towards their patients [22]. Female physicians are more sensitive to the physician-patient relationship, more accepting of the patient’s feeling, and more open to psychosocial factors in health care [23]. Patients might thus consider female physicians more approachable and expect fewer reservations from them about health-related Internet use.

Younger physicians (≤46 years) were less confident about their ability to cope with perceived difficulties of health-related Internet use. This might result from the fact that they have had less experience with patient care. Older physicians have experienced many years of patients bringing information from other media, such as the television or the newspaper, to consultations. Paying attention to patients’ health-related Internet use during the physicians’ training might be worthwhile.

Limitations of the present study

Although the response rate of our study was comparable to the response rate of 53% in a study among US physicians [12], it might be the case that the physicians who chose to complete our questionnaire are not representative for all Dutch rheumatologists and oncologists.

In addition, it should be considered that we made use of self-perceived measures. It might have been difficult for physicians to estimate the amount of patients using the Internet.

Conclusion

Almost all physicians experienced their patients raising information from the Internet during a consultation. However, this was still not a daily occurrence. Physicians were moderately positive about the consequences of health-related Internet use for their patients, the physician-patient relation, and the health care. The physicians indicated that they can cope with the perceived difficulties of health-related Internet use. However, despite the literature advising physicians to assist their patients in their Internet use, physicians only seldom refer them to health-related Internet sites. Maybe offering an up-to-date list with accredited websites for patients would help and stimulate physicians to refer their patients.

References

Gordon MM, Capell HA, Madhok R (2002) The use of the Internet as a resource for health information among patients attending a rheumatology clinic. Rheumatology (Oxford) 41:1402–1405

Kim HA, Bae YD, Seo YI (2004) Arthritis information on the Web and its influence on patients and physicians: a Korean study. Clin Exp Rheumatol 22:49–54

Neame R, Hammond A, Deighton C (2005) Need for information and for involvement in decision making among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a questionnaire survey. Arthritis Rheum 53:249–255

Richter JG, Becker A, Specker C, Monser R, Schneider M (2004) Disease-oriented Internet use in outpatients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Z Rheumatol 63:216–22, Article in German

Hay MC, Cadigan RJ, Khanna D, Strathmann C, Lieber E, Altman R, McMahon M, Kokhab M, Furst DE (2008) Prepared patients: internet information seeking by new rheumatology patients. Arthritis Rheum 59:575–582

Bass SB, Ruzek SB, Gordon TF, Fleisher L, McKeown-Conn N, Moore D (2006) Relationship of Internet health information use with patient behavior and self-efficacy: experiences of newly diagnosed cancer patients who contact the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Information Service. J Health Commun 11:219–236

van Lankveld WG, Derks AM, van den Hoogen FH (2006) Disease related use of the internet in chronically ill adults: current and expected use. Ann Rheum Dis 65:121–123

Suarez-Almazor ME, Kendall CJ, Dorgan M (2001) Surfing the net—information on the World Wide Web for persons with arthritis: patient empowerment or patient deceit? J Rheumatol 28:185–191

Diaz JA, Sciamanna CN, Evangelou E, Stamp MJ, Ferguson T (2005) Brief report: what types of Internet guidance do patients want from their physicians? J Gen Intern Med 20:683–685

Dickerson S, Reinhart AM, Feeley TH, Bidani R, Rich E, Garg VK, Hershey CO (2004) Patient Internet use for health information at three urban primary care clinics. J Am Med Inform Assoc 11:499–504

Potts HW, Wyatt JC (2002) Survey of doctors' experience of patients using the Internet. J Med Internet Res 4:e5

Murray E, Lo B, Pollack L, Donelan K, Catania J, Lee K, Zapert K, Turner R (2003) The impact of health information on the Internet on health care and the physician-patient relationship: national US survey among 1,050 US physicians. J Med Internet Res 5:e17

van Uden-Kraan CF, Drossaert CHC, Taal E, Lebrun CEI, Drossaers-Bakker KW, Smit WM, Seydel ER, van de Laar MAFJ (2008) Coping with somatic illnesses in online support groups. Do the feared disadvantages actually occur? Comput Hum Behav 24:309–324

van Uden-Kraan CF, Drossaert CHC, Taal E, Shaw BR, Seydel ER, van de Laar MAFJ (2008) Empowering processes and outcomes of participation in online support groups for patients with breast cancer, arthritis and fibromyalgia. Qual Health Res 18:405–417

Swanborn PG (1994) Methoden van sociaal-wetenschappelijk onderzoek. Meppel, Boom

van Uden-Kraan CF, Drossaert CHC, Taal E, Smit WM, Bernelot Moens HJ, Siesling S, Seydel ER, van de Laar MAFJ (2009) Health-related Internet use by patients with somatic diseases: frequency of use and characteristics of users. Inform Health Soc Care 34:18–29

Ahmad F, Hudak PL, Bercovitz K, Hollenberg E, Levinson W (2006) Are physicians ready for patients with Internet-based health information? J Med Internet Res 8:e22

Hart A, Henwood F, Wyatt S (2004) The role of the Internet in patient-practitioner relationships: findings from a qualitative research study. J Med Internet Res 6:e36

Gerber BS, Eiser AR (2001) The patient physician relationship in the Internet age: future prospects and the research agenda. J Med Internet Res 3:e15

Shepperd S, Charnock D, Gann B (1999) Helping patients access high quality health information. BMJ 319:764–766

Pal B, Laing H, Estrach C (1999) A cyberclinic in rheumatology. J R Coll Physicians Lond 33:161–162

Meeuwesen L, Schaap C, van der Staak C (1991) Verbal analysis of doctor-patient communication. Soc Sci Med 32:1143–1150

Maheux B, Dufort F, Béland F, Jacques A, Lévesque A (1990) Female medical practitioners. More preventive and patient oriented? Med Care 28:87–92

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw), the Dutch Arthritis Association, and the Comprehensive Cancer Centre Noord Oost (IKNO).

We would like to thank the Dutch Society for Rheumatology (NVR) and the Dutch Society for Internal Medicine (NIV) for providing us with the addresses of all the rheumatologists and oncologists in the Netherlands.

We would like to thank Chanel Peek for her contribution in the data collection of this study.

Disclosures

None

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

van Uden-Kraan, C.F., Drossaert, C.H.C., Taal, E. et al. Experiences and attitudes of Dutch rheumatologists and oncologists with regard to their patients’ health-related Internet use. Clin Rheumatol 29, 1229–1236 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-010-1435-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-010-1435-1