Abstract

Improving knowledge of existing levees through investigation and monitoring is an important step in evaluating their safety and that of the surrounding area. Nevertheless, these activities are complex due to the considerable levee length and the high spatial variability of soil composing the body and foundation, especially when paleo-rivers are present. In order to investigate the reliability of new advanced techniques proposed for characterizing the soil stratigraphy and the seepage condition within the levee foundation, a new test site was realized along the Adige River in Bolzano Province (Italy). Here, five boreholes, drilled in a 20-m-side square area straddling the embankment, host four different types of monitoring equipment, among which some are Distributed Fiber Optical Sensors (DFOS), here used for detecting the temperature variations along the well. The present paper focuses on the critical analysis of the preliminary results obtained with DFOS and their comparison with data obtained using traditional pressure and temperature probes. The monitoring data collected in the field during the passage of a flood that occurred on 5th August 2021 are used to better understand the hydraulic behavior and the safety conditions of the levee but also to fully assess the reliability and potential of DFOS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Every year, levee and dike collapses cause many casualties worldwide, as well as huge financial and social losses, especially in highly developed areas. The surveying and monitoring of embankment structures are complicated by the considerable length of these structures and the high variability of soil constituting the embankment bodies and their foundation, especially when ancient paleo-rivers are present. On the other hand, understanding and monitoring the hydraulic behavior of levees are strategies that guarantee their safety conditions. Finally, to define the appropriate monitoring tools and programs, it is necessary to understand the specific site potential failure modes (Oguz et al. 2022; Zwanenburg et al. 2018; Su and Kang 2013).

In recent decades, non-invasive or minimally invasive techniques have been developed with the aim of monitoring large portions of embankments. Of course, geophysical methods play a crucial role in evaluating the stability conditions of dams, embankments, and slopes. Among them, geo-electrical measurements, which can investigate variations of soil composition and water saturation, are suitable for hydro-geological studies and detecting weak zones (Inazaki and Sakamoto 2005; Cho and Yeom 2007; Sjödahl et al. 2009; Binley et al. 2010, 2015; Perri et al. 2014; Busato et al. 2016; Amabile et al. 2020a, b; Hojat et al. 2021; Zhou et al. 2022a, b).

In the two past decades, some researchers have found temperature to be a good indicator of seepage within the levee or earth dam body and their foundation (Radzicki 2014; Utili et al. 2015; Bersan et al. 2018; Cola et al. 2021; Johansson and Sjödahl 2004; Zhu et al. 2009; Brothier et al. 2018; Su et al. 2018; Li et al. 2022; Cheng et al. 2021; Dalla Santa et al. 2023). The principle at the basis of detection by temperature sensing consists of assuming that when a normal flow regime exists, temperature fluctuations are driven by heat conduction from the air toward the foundation, on a seasonal basis. On the contrary, when abnormal seepage flows take place, the amplitude of temperature fluctuations increases as advection from the water upstream becomes overly significant.

In order to have an effective system for the detection of temperature distribution and variation along a long stretch of the river levees, the distributed optical fiber sensors (DFOSs) could be very convenient. These sensors are innovative sensors based on optical fiber technology which have undergone substantial advancements and witnessed widespread adoption within the domain of engineering and, among others, within the field of Civil Structural Health Monitoring. This progression is well documented in the works of many researchers, e.g., Schenato (2017), Zhang and Xue (2019), Ye et al. (2022), Zhou et al. (2022a, b), Schenato et al. (2022), Zhu et al. (2023), Brezzi et al. (2023), and Höttges et al. (2023). The heightened prevalence of DFOS in engineering can be attributed to the manifold opportunities that this technology affords in comparison to traditional sensor systems, mainly the possibility of measuring temperature distribution for long distances with high resolution and precision. With regards to hydraulic infrastructures, while DFOS systems are commonly used for dam monitoring on more than one hundred large earth dams, tailing dams, and canals (see for instance, Su et al. 2014; Goltz 2011; Johannson et al. 2015; Fabritius et al. 2017; Cejka et al. 2018; Bekele et al. 2023), their application in monitoring river or sea dikes and existing levees is relatively limited only on a few cases (Bersan et al. 2018; Cola et al. 2021; Abbasimaedeh et al. 2021). Considering these aspects, new good experiences during real flooding events could lead to more widespread use of this technology. To this aim, to detect and track variations in temperature, it can be convenient to integrate traditional field monitoring with DFOS. Two methods are employed for seepage detection with DFOS: the passive gradient method, relying on temperature changes caused by seepage water, and the active heat pulse method, which uses hybrid sensor cables combining optical fiber and copper wire to warm the ground and identify areas with high water saturation or flow regions by observing the temperature dissipation around the cable.

For evaluating the potentiality of DFOS for levee investigation, in 2016, the authors made a first attempt. In that first attempt, a single DFOS for temperature measurement was installed within a trench about 350 m long at the foot of the right embankment of Adige River (Cola et al. 2021): with the same cable, 3 spans at 3 levels with a vertical interspace of 50 cm were realized. The aim was to evaluate the DFOS capability for identifying the piping occurrence in a section specifically known for this type of problem even if in that section a cut-off wall was realized more than 20 years ago.

Although the results from this initial setup suggested the possible occurrence of a localized seepage during a flood event, its identification was not conclusive or definitive. However, these findings prompted to perform further attempts to exploit different sensor configurations. Consequently, the present paper deals with a second attempt carried out in a field test close to the previous one and with similar issues. Here, traditional sensors were combined with DFOS. All the devices were installed in vertical holes to reduce soil disturbance during installation. As far as the authors are aware, this is the first case of a DFOS application installed in a vertical hole in levee monitoring in Italy.

During the realization of the new test field, in order to characterize the embankment structure and its geotechnical behavior thoroughly, five boreholes were drilled at the corners and the center of a 20-m-side square-shaped area, straddling the right embankment (Fig. 1a). Several in situ and laboratory tests were conducted to fully characterize the soil stratigraphy, with particular regard to hydraulic parameters. In each vertical borehole, different monitoring instruments were placed side-by-side, specifically standard piezometric and thermal probes and innovative sensors, such as DFOS and cables for cross-hole electrical resistivity tomography.

The monitoring campaign is ongoing so that the potential of DFOSs as monitoring techniques can be thoroughly assessed. To this aim, the temperature and pressure data collected during future flooding events will be analyzed to understand and characterize the hydraulic behavior of the embankment under different river water levels and define the safety conditions of the embankment in this area. Here, the data collected during a first occurred medium flooding event are presented and discussed.

The field test site

The Adige Valley has been subjected to major floods in the past, since the collapse of 1882, in which the Adige River embankments failed in ten different sections. The most devastating event of the twentieth century occurred in 1966 when the city of Trento was completely submerged. A landside instability mechanism on the left levee embankments, near the village of Salorno, caused a collapse in 1981 that flooded the entire surrounding area (Cola et al. 2021). After this event, the Mountain Water Authority of the Province of Bolzano undertook an intensive monitoring program of the “health” of Adige levees, promoting monitoring activities of the levee investigation, experimental studies, and modeling (Bossi et al. 2018; Amabile et al. 2020a, b; Pozzato et al. 2020; Cola et al. 2021; Schenato et al. 2022; Fabbian et al. 2022).

Fluvio-glacial and lacustrine sediments constitute the deep stratigraphy of the Adige Valley. Above these, the more recent soil deposits, characterized by alluvial sediments transported here by the river and near landslide bodies, are present. Consequently, the valley presents high heterogeneity and interdigitation of different materials, as has emerged from the various site investigations carried out so far.

Before the nineteenth century, the river thalweg developed freely with a meandering form that migrated along the narrow field. Then, several anthropic interventions, such as the realization of straight embankments, confined and rectified the river in a fixed bed. Traces of ancient meanders are easily recognizable in aerial photographs or satellite images (Angelucci 2013). In many lineaments, the new levee system crosses the ancient paleo-river, and in the past, several of the observed levee collapses seemed to occur at those intersection points (Cola et al. 2021).

The field test here presented is along the right side of the Adige River, just after the bridge of Salorno (Bolzano, Italy) and a hydrometric station of the Bolzano Province (Fig. 1) and before the section of the first test. The main body of the levee was built in the late nineteenth century, and a country-side berm was added in 1983. This site was selected because it has no internal human interventions and because of its proximity to the A22 Highway. As the highway here runs parallel and very close to the levee, a possible collapse can have dangerous impacts on people and the economy. Occurrences of sand boiling, which typically necessitate the implementation of hazard mitigation protocols like sandbag deployment, were not detected in this area before or during the investigations. Nevertheless, several minor water inflows were observed during the most intense flood events. These piping were characterized by the discharge of clear water, indicating no evident signs of internal erosion. However, while not indicative of erosion, these occurrences serve as a warning signal, emphasizing the need for future structural interventions to improve the levee against potential risks, the latter to be better understood through monitoring of the area.

Geotechnical investigation

In May and June 2021, a careful site characterization was carried out by means of the following geotechnical investigations:

-

1.

Five boreholes were drilled at the corners and the center of a 20-m-side square area (Fig. 1a). The central borehole (S3), located on the top of the levee, has a depth of approximately 30 m, while those located at the corners are about 25 m deep, in order to reach roughly the same elevation. S1 and S2 are situated on the side of the land bank, and S4 and S5 are situated on the side of the river bank.

-

2.

Eleven undisturbed samples were collected with the gel pusher (GP) sampling technique in S3, while 10 undisturbed Shelby samples and 16 reworked samples were collected in the other holes. GP sampling is a technique developed in 1999 by Kiso-Jiban Consultants and the Yokohama National University as an alternative to the expensive freeze sampling method for obtaining high-quality undisturbed granular soil samples (Huang et al. 2008; Yusa et al. 2017). The technique is used here for the large presence of granular materials that cannot be sampled with traditional methods (Fabbian et al. 2023).

-

3.

SPT and Lefranc tests were performed on the layer below WT.

-

4.

Twenty thermal characterization tests were carried out on-site.

-

5.

Other in situ permeability tests were performed using an experimental device properly constructed to determine the permeability of coarse-grained soils (sand and sandy gravels).

The in situ investigation was completed by laboratory tests performed on collected undisturbed samples to determine particle size distribution, Atterberg limits, organic material content, hydraulic conductivity tests in triaxial cells, shear resistance, and compressibility of the soils.

The survey made it possible to define the soil stratigraphy, here reported in Fig. 2, in detail. Due to their proximity, the boreholes went through a similar stratigraphic succession, differentiated only by the composition of the embankment structure and by small lateral variations in the sediment granulometry. The embankment is constituted by fill material, consisting of poorly graded gravel with silt and sand or poorly graded sand with silt (GP-GM or SP-SM) according to the unified soil classification system (USCS). The foundation can be divided into 9 layers with variable thicknesses from 1 to 5 m. Specifically, the layers identified from top to bottom are

-

1.

Silty sand or poorly graded sand with silt (SM or SP-SM)

-

2.

Silty sand with Peat (SM with PT)

-

3.

Well-graded sand with sand with silt and gravel (SW-SM)

-

4.

Well-graded gravel with silt and sand (GW-GM)

-

5.

Peat or organic silt (PT or OL)

-

6.

Well-graded sand with sand with silt (SW-SM)

-

7.

Silty sand (SM)

-

8.

Silt or organic silt or peat (ML or OL or PT)

-

9.

Well-graded sand with silt or organic silt (SW-SM or OL)

The laboratory and on-site tests permitted to define hydraulic and mechanical parameters for seepage and stability analyses. Of course, these parameters present a great variability, and in the selection of representative values, more importance is given to on-site tests, considered more reliable. The main geotechnical parameters of soil layers are also listed in Table 1.

In normal conditions, when the river is not subjected to high flooding, the water table (WT) on the landside is about 7 m from the embankment crest.

Monitoring instrumentation

As shown in Fig. 2, the following instrumentation was installed in each borehole:

-

1.

1 DFOS to measure temperature variation along the vertical profile

-

2.

24 electrodes to perform 3D electrical resistivity tomography (ERT) surveys; the ERT interrogator in use is capable of testing three holes at a time, in cross-hole mode, to obtain a 3D map of the resistivity of the foundation soil. No comment on the measure performed with this device is reported here for the sake of space

-

3.

2 combined sensors were installed in each hole at different depths. Each sensor is formed by a pressure transducer (TP) and thermometric transducer (TT), with an accuracy of 2 cm of water column and 0.1 °C, respectively. All the sensors were previously calibrated in the laboratory and are hourly interrogated with an A/D controller.

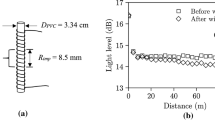

DFOSs are the only available contact sensor technology capable of providing the measurement of temperature and/or strain with sufficient spatial resolution in soil over an extensive length. In this application, a DFOS for temperature measurement, also named distributed temperature sensor (DTS), is adopted. If interrogated with a Raman interrogator (Sensornet’s Oryx SR DTS), it provides a temperature datum along its entire length with a spatial resolution of 2 m and an accuracy of 0.1 °C. In particular, the cable (Fig. 3a) houses 2 multimode fibers (in addition to a conductive strand for active heating mode, not used in this case). It has an external diameter of 4 mm and withstands a minimum bending diameter without tension of 12 cm. It was installed vertically in a U-shaped configuration, anchored externally to a 60-mm diameter micro-slotted pipe. A specific support was designed to protect the cable at the bottom of the hole and prevent it from being bent too tightly (Fig. 3b). Once the drilling was completed, the slotted pipe and fiber cable were lowered into the hole, and the borehole casing was removed. To allow this operation, the fiber optic cable was previously cut to the length needed for each borehole and then spliced to the cable from the adjacent holes to create a single optical cable that can be interrogated in a dual-ended configuration from a unique location (Fig. 3c). The fiber running from one borehole to another was protected within a PVC corrugated pipe placed in a small trench.

In order to improve accuracy and to calibrate the FO cable, it is good practice to perform a calibration bath, which consists of placing about 20 m of fiber in a tank full of water at a known temperature, in order to translate the measurement of the difference between the measures of the fibers and at least two reference sensors (Schenato et al. 2022). Thermal bath was performed at each measurement campaign reported in the present paper (Fig. 3d).

Some examples of temperature profiles along the central borehole (S3) are presented in Fig. 4. Except for two measurements collected in October 2021 and September 2022, all the others were in spring and summer. Even though few measurements are available in winter, seasonal fluctuations, due to solar radiation and heat exchange with the atmosphere, are well visible in the embankment body and in the first foundation layer. During the summer, the soil receives more intense and prolonged solar radiation, which leads to an increase in soil temperature as the soil absorbs the heat from the sun; in contrast, during winter, the solar radiation decreases, and the ground gradually cools down. The thermal conductivity of soils is generally low, and the seasonal fluctuations have effects only in the upper layer (5–7 m). The deeper layers are insensitive to these fluctuations, and the temperature remains quite constant and equal to the mean annual temperature of the external air of the considered site (Cunat et al. 2009).

Due to the thermal inertia of the ground and the particular meteoric conditions occurring each year, the point of maximum warming could be in 1 day of the summer: for instance, in the 2 years here presented, the maximum temperature is recorded at the 25th of June 2021 and at the 5th of August 2022. For the same reasons, the coldest time is at the end of winter or in early spring. In the series here presented, we have not captured the absolute minimum profile: the lowest observed temperatures are on the 7th of April 2022, which still showed a temperature gradient positive in the first 3–4 m, thus indicating that the temperature was already increasing and probably the absolute minimum occurred previously that date. For the site under consideration, the mean annual temperature is around 11 °C, as measured in the lowest part of quite all the profiles.

Of course, periodic measurements are essential for ascertaining ground temperature at different moments, as variations in thermal conditions arising from hydraulic anomalies are contingent upon a baseline reference measurement.

Observation during the flooding event on the 5th of August 2021

After the installation of the monitoring system, only one notable flood wave, due to an intense rainfall that occurred north of Bolzano, affected the river on the 5th of August 2021.

In Fig. 5a, the piezometric levels recorded by all the TP are compared with the river water level recorded at the hydrometric station. It can be observed that the flood produced an increase in the water river level of about 4.2 m in only 11 h, reaching the maximum elevation of 213.4 m a.s.l. (about 70 cm below the embankment crest) around 11:00 am on the 5th of August 2021. Meanwhile, numerous springs formed along the landside of the levee. Near the experimental site, four springs of a modest entity were identified; they were characterized by the emersion of clean water, which indicated that the water did not internally erode the embankment.

TP7, TP8, and TP10, located inside the well on the riverside, are most sensible to the river level oscillation: they recorded a variation of about 3–3.8 m, reaching the highest piezometric levels. This behavior was foreseeable for TP10, located at a shallow depth and very close to the riverbed. Conversely, it was less predictable for TP7 and TP8, which are located in the sandy layers no. 5 and no. 7 (see soil stratigraphy in Fig. 2). This appears anomalous if compared with the response of TP9, located at a small horizontal distance in the same layer no. 5. In addition, the piezometric level at TP7 and TP8 began to rise after 1–2 h, which is exceptionally quick when compared to the 4- to 5-h delay showed by the other sensors. This anomalous behavior has to be verified in the future, because it is possible to suppose that it is related to a not correct sealing of the S4 well at the top. The pressure variation registered during the flood by all the other sensors is only 1–1.2 m and seems to reduce its value by moving from the waterside (TP5 and TP6) toward the landside (TP1, TP2, TP3, and TP4).

Starting from the 3rd of August up to flood peak, the water temperature of the river dropped down by about 1 °C, as Fig. 5b shows. Again, only TT10, likely due to its proximity to the riverbed, recorded a comparable drop but localized in time in the rising phase of the water river level, when the flood activated the seepage. On the contrary, TT5, TT6, TT7, and TT8 recorded a temperature increase of about 1.5 °C, with some delay with respect to the passage of the flood wave. This seems ascribable to the migration of warm water previously residing in deeper layers, possibly caused by the activation of seepage between the two levee sides.

Note that in well S3, where TT5 and TT6 are located, the slotted pipe was still empty at that moment, so vertical movements of water and air inside the well are possible. Consequently, data recorded by TT5 and TT6 may be influenced by the external air temperature (about 25 °C at the flood peak time).

Figure 6 illustrates the piezometric line at different times during the flood event in cross-sections S1–S3–S5. As previously observed, the flood wave passage did not significantly affect the water pressure in deep layers, where the piezometric head went above the ground surface only in the central part of the event. This induces the hypothesis that the springs observed on the landside of the levee were induced by a seepage phenomenon that developed entirely within the bank body or at the interface with layer no. 2. They could also be related to some paths locally excavated by animals (e.g., moles or mice), because some small holes attributed to the entrance of animal caves were subsequently found on the landside slope of the levee in the same area.

Figure 7 compares temperature profiles measured with DFOS in boreholes S1 (landside), S3 (center of the levee), and S5 (waterside) during the flood event (5th of August) and 2 weeks before (21st of July), when the water river level was low. Figure 7a shows the temperature profiles; Fig. 7b reports the temperature variations observed in August with respect to July. In the following, the temperature profile recorded on July 21 is assumed as the profile existing just before the rainfall and flood event. This is because the weather in the days before the rainfall had been stable, and it is possible to assume that the soil temperature had not changed significantly.

A significant temperature decrease in the upper layers is observed in landside well S1. It should be noted that on the landside, the WT is normally at 207.4 m a.s.l. Therefore, due to solar irradiation and high air temperature (the daily peak of air temperature in summer can arrive higher than 30 °C), in July, the soil temperature above the WT is very high. During the flood, the soil in the shallow 4–5 m saturated rapidly due to the infiltration of cold rainwater, and the soil temperature dropped by about 8 °C. In the waterside well, a similar temperature drop is observed, but only in the first 2–3 m, because the wellhead is only 2 m above WT. Finally, the trend recorded in borehole S3 is completely different, and a small decrease of 2 °C in temperature is observed only in the upper 2 m; this behavior could be explained considering that the soil composing the levee is well compacted and less permeable in the upper part and the rain infiltrates with higher difficulty. Moreover, since the slotted pipe in borehole S3 was still open, the air circulation can affect the temperature recorded inside the well by the DFOS.

In addition, in central well S3, the temperature exhibits a variation of 1 to 2 °C in the deep layers as the flood wave passed. This confirms the trend recorded by traditional sensors. Even if the temperature measured by DFOS is 1 to 2 °C, different from that recorded by the temperature probes, the temperature variations measured with the two monitoring systems are similar.

Discussion

The previous section has presented the data acquired during an important flood event that occurred on the 5th of August 2021. The measurements obtained provided remarkable information. Considering the traditional sensors, it has to be noted that, excluding the sensor located at a small depth below the riverside bank, all the others are in the permeable layers in the levee foundation, at a depth from 12 to 17 m from the levee top and separated by relatively impermeable layers from the riverbed. Despite the significant increment in the river level, the data showed limited pressure increases, suggesting that the deeper layers are not significantly affected by seepage, which probably affected only the levee body and the shallower layers. The same observation can be obtained from the temperature curves; only the sensor in the riverbank exhibited a temperature change associated with the variation of the river water temperature recorded at the nearby hydrometric station. On the other hand, DFOS in the well at the site corners measured a significant temperature drop limited to the shallower layers above the WT (up to 4 m from the wellhead). Before the flood occurrence, the soil above the WT exhibited very high temperatures, likely due to the high external temperature and seasonality. During the flood, in the wells on the riverside, the temperature decreased from 22 to 13 °C due to infiltration of the river water, which has a temperature of about 12.5 °C. Also, data recorded by DFOS evidenced an analogous decrease in temperature in the landside borehole, in this case also justifiable considering infiltration of the rainwater and the presence of piping observed during the event. No significant decrease in temperature is recorded in the hole located at the center of the embankment; however, the S3 well is not yet clogged and cannot therefore be considered representative of the behavior of the levee. Furthermore, the absence of additional well placements at the central axis of the levee precludes the possibility of a comparative analysis.

In the first attempt of using DFOS for temperature detection during seepage, carried out in a site very close to the one here described (Cola et al. 2021), DFOS was horizontally installed in a trench long 350 m positioned at the toe of an embankment. The measurement carried out in October 2018 during an intense flood event revealed that the flood-induced seepage produced the displacement of the pre-existing water, causing a decrease in soil temperatures toward the temperature of the adjacent river. Thanks to the data acquired with DFOS, an inversion of the temperature gradient observed within a specific section chainage suggested the presence of faster upward seepage flow paths located close to some gravel lenses, with the latter partially discerned during the geotechnical investigation. The interpretation of DFOS data during the flood event presented challenges attributable to the constrained temperature variations and the necessity for an approximate interpretation of the seepage flow dynamics.

In this second attempt, the placement of fibers within vertical boreholes was chosen to have more readily discernible temperature fluctuations with depth. This is clearly observed in the different interrogations performed in the different seasons, but also with the data acquired with the flood event on the 5th of August 2021, when these fibers offer insights into the specific depths at which saturation or preferential filtration pathways manifested.

In this attempt also, the DFOS demonstrated its effectiveness in measuring temperature fluctuations in the soil. A clear outcome of this investigation is that the seasonal temperature fluctuations in the first few meters of soil are not negligible, so periodic measurements are necessary in order to establish a reference measurement in the case of flooding. On the other hand, the soil temperature variations induced by seepage are very small especially in the deep layers. Consequently, for future installations, it could be better to concentrate the attention on the upper layers (levee body and the first two layers in the foundations).

Further measurements and analyses will be carried out under different flood conditions in the future, in order to better understand the possibilities of using DFOS in monitoring embankment structures, which can be more accurately evaluated.

Conclusions

The article has presented the results of a comprehensive study carried out on a section of the right levee of the Adige River near Bolzano (north-east of Italy). In order to evaluate the health state of the levee and the presence of seepage phenomena in the subsoil and, moreover, to test new methods of investigation and monitoring, a test site was realized. In a 20-m-side square area, straddling the embankment, conventional sensors along with DFOS for measuring pressure and temperature evolution were installed in 5 boreholes with the aim of detecting the layer in which the seepage occurs. In addition, a very detailed characterization carried out on-site and on the collected samples permitted the reconstruction of the subsoil stratigraphy and identification of the more permeable layers.

This study has allowed assessment of the applicability of this system and, in particular, the approach of monitoring deep soil temperatures to detect seepage flow from the river. In particular, the vertical profiles of temperature acquired with DFOS clearly showed that both the rain falling to the ground and water infiltrating from the river advanced inside the embankment, but not significantly in the deeper layers. This process is also confirmed by the data temperature acquired with traditional sensors. In fact, water pressure variations observed in the deep layers are quite low and seem to indicate that no significant seepage phenomena are activated in the deep layers.

Additionally, some preliminary conclusions on the adopted system can here be drawn. Thanks to breakthroughs in DFOS in recent decades, it is now possible to obtain high spatial coverage and spatial resolution. This possibility avoids having to previously choose the precise location of each sensing point, as happens for traditional probes. For example, in the analyzed case, by monitoring the temperature vertical profile of DFOS, one can detect the depth at which seepage occurs. This detection is more difficult to obtain through punctual sensors given the need for numerous sensors, and moreover, their positions must be determined in advance. Undeniably, the combination of different sensors provides more detailed information on the levee behavior, and the data acquired by one sensor is useful to validate data recorded by the others and vice versa.

With respect to conventional sensors that provide the temporal evolution of temperature and pressure in some single predetermined points, DFOS presents the advantages of both directly measuring temperatures along vertical wells during the field campaign and being economically convenient, if one considers the ratio between cost and amount of acquired data. Furthermore, DFOSs have no moving parts and no required maintenance and have an expected lifespan of more than 20 years. On the other side, if a safe and temperature-controlled structure for hosting the fiber optic interrogator is not available, measures with DFOS require the presence of an operator, which strongly reduces the possibility of having detailed information over time. Moreover, the interrogator has a great impact on the cost of the overall system, which requires a large investment or must be shared between several sites to reduce costs.

With regard to the positioning of DFOS, to evaluate the presence of local more permeable water paths that permit the migration of water from waterside to landside, optical fibers must be on the path of water. In other words, both cable positions and the installation technique play a crucial role. Generally, a dense distribution of the fiber cable is needed to monitor the full section of the levee body. This can be achieved by installing a zigzagging cable with appropriate spacing between parallel and horizontal lines on the landside portion or by installing the fiber inside a series of vertical holes. The installation of the cable can become a complex and invasive problem, especially when being used to test already existing embankments. However, optical fibers can be a very efficient and cost-effective solution for monitoring new earth structures, where optical fibers can easily be installed during construction.

Of course, temperature variation is an indirect proxy of seepage, and it is better to use DFOS in combination with other monitoring techniques (i.e., other temperature transducers and water pressure transducers) in order to have a more precise and detailed vision of what occurs in the soil. Finally, since it is best to carefully calibrate both traditional and DFOS temperature sensors, the thermic bath procedure adopted in this study proved simple yet effective and can be applied both in the laboratory and on-site. The potential for broadening the application of this methodology to substantial constructions like embankments holds significant appeal for the authorities devoted to land control. This is because it can be integrated as an advanced early warning system in addition to visual inspections, enabling swift protective measures to be initiated in response to potential indicators of embankment structural instability.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [NF], upon reasonable request.

References

Abbasimaedeh P, Tatin M, Lamour V, Vincent H, Bonelli S, Garandet A (2021) On earth dam leak detection based on using fiber-optic distributed temperature sensor (case study: Canal embankment on the Rhône River, France). In: New approaches of geotechnical engineering: soil characterization, sustainable materials and numerical simulation: Proceedings of the 6th GeoChina International Conference on Civil & Transportation Infrastructures: from Engineering to Smart & Green Life Cycle Solutions--Nanchang, China, 2021 6. Springer International Publishing, pp 44–57

Amabile A, Lopes BCFL, Pozzato A, Benes V, Tarantino A (2020a) An assessment of ERT as a method to monitor water content regime in flood embankments: the case study of the Adige River embankment. Phys Chem Earth Parts A/B/C 120:102930

Amabile A, Pozzato A, Tarantino A (2020b) Instability of flood embankments due to pore-water pressure build-up at the toe: lesson learned from the Adige River case study. Can Geotech J 57(12):1844–1853

Angelucci DE (2013) La valle dell’Adige: genesi e modificazione di una grande valle alpina come interazione tra dinamiche naturali e fattori antropici. Atti del Convegno: il fiume, le terre, l’immaginario. L’Adige come fenomeno storiografico complesso. Rovereto, 21–22. Edizioni Osiride, SBN: 978-88-7498-257-8

Bekele B, Song C, Eun J, Kim S (2023) Exploratory seepage detection in a laboratory-scale earthen dam based on distributed temperature sensing method. Geotech Geol Eng 41(2):927–942

Bersan S, Koelewijn AR, Simonini P (2018) Effectiveness of distributed temperature measurements for early detection of piping in river embankments. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 22(2):1491–1508

Binley A, Cassiani G, Deiana R (2010) Hydrogeophysics: opportunities and challenges. Bollettino di Geofisica Teorica ed Applicata 51(4):267–284

Binley A, Hubbard SS, Huisman JA, Revil A, Robinson DA, Singha K, Slater LD (2015) The emergence of hydrogeophysics for improved understanding of subsurface processes over multiple scales. Water Resour Res 51(6):3837–3866

Bossi G, Bersan S, Cola S, Schenato L, De Polo F, Menegazzo C, Boaga J, Cassiani G, Donini F, Simonini P (2018) Multidisciplinary analysis and modelling of a river embankment affected by piping. In: Internal erosion in earthdams, dikes and levees: Proceedings of EWGgIE 26th Annual Meeting. Springer International Publishing, pp 234–244. https://doi.org/10.32075/17ECSMGE-2019-0632

Brezzi L, Schenato L, Cola S, Fabbian N, Chemello P, Simonini P (2023) Smart monitoring by fiber-optic sensors of strain and temperature of a concrete double arch dam. In: Ferrari A, Rosone M, Ziccarelli M, Gottardi G (eds) Geotechnical engineering in the digital and technological innovation era. CNRIG 2023. Springer Series in Geomechanics and Geoengineering. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34761-0_20

Brothier C, Martinot F, Garandet A (2018) New monitoring techniques for long linear dikes, Q.103-R.34. In: Proceedings of the 26st ICOLD congress, July 1–7. Vienna, pp 556–578

Busato L, Boaga J, Peruzzo L, Himi M, Cola S, Bersan S, Cassiani G (2016) Combined geophysical surveys for the characterization of a reconstructed river embankment. Eng Geol 211:74–84

Cejka F, Beneš V, Glac F, Boukalova Z (2018) Monitoring of seepages in earthen dams and levees. Int J Environ Impacts 1(3):267–278

Cheng L, Zhang A, Cao B, Yang J, Hu L, Li Y (2021) An experimental study on monitoring the phreatic line of an embankment dam based on temperature detection by OFDR. Opt Fiber Technol 63:102510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yofte.2021.102510

Cho IK, Yeom JY (2007) Crossline resistivity tomography for the delineation of anomalous seepage pathways in an embankment dam. Geophysics 72(2):G31–G38

Cola S, Girardi V, Bersan S, Simonini P, Schenato L, De Polo F (2021) An optical fiber based monitoring system to study the seepage flow below the landside toe of a river levee. J Civ Struct Heal Monit 11(3):691–705. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13349-021-00475-y

Cunat P, Beck YL, Fry JJ, Courivaud JR, Fabre JP, Faure YH, Radzicki K (2009) Surveillance of dike ageing by distributed temperature measurement along a _ber optic. Proceedings of HYDRO 2009, Hydropower & Dams, Aqua Media International Ltd, Wallington, UK, 338–341

Dalla Santa G, Fabbian N, Cola S (2023) Investigating the effects of water levels measured in two nearby rivers on groundwater pore pressures regime. In: Ferrari A, Rosone M, Ziccarelli M, Gottardi G (eds) Geotechnical engineering in the digital and technological innovation era. CNRIG 2023. Springer Series in Geomechanics and Geoengineering. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34761-0_22

Fabbian N, Cola S, Simonini P, De Polo F, Schenato L, Tedesco G, Marcato G, Dalla Santa G (2022) Innovative and traditional monitoring system for characterizing the seepage inside river embankments along the Adige River in Salorno (Italy). ISFMG 2022, London. https://www.issmge.org/publications/publication/innovative-and-traditional-monitoring-system-for-characterizing-the-seepage-inside-river-embankments-along-the-adige-river-in-salorno-italy. Accessed 4–8 Sep 2022

Fabbian N, Simonini P, De Polo F, Cola S (2023) First experiences with gel-push sampler for testing coarse alluvial soils under a river levee. In: Ferrari A, Rosone M, Ziccarelli M, Gottardi G (eds) Geotechnical engineering in the digital and technological innovation era. CNRIG 2023. Springer Series in Geomechanics and Geoengineering. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34761-0_8

Fabritius A, Heinemann B, Dornstädter J, Trick T (2017) Distributed fibre optic temperature measurements for dam safety monitoring: current state of the art and further developments. In: Proceedings of the Annual South African National Committee on Large Dams (SANCOLD) Conference, Centurion, Tshwane, South Africa

Goltz M (2011) A contribution to monitoring of embankment dams by means of distributed fibre optic measurements. Doctoral thesis (Doktor der Technischen Wissenschaften) - Fakultät für Bauingenieur Wissenschaften, Leopold-Franzens Universität Innsbruck, Austria, p 202

Hojat A, Ferrario M, Arosio D, Brunero M, Ivanov VI, Longoni L, Madaschi A, Papini M, Tresoldi G, Zanzi L (2021) Laboratory studies using electrical resistivity tomography and fiber optic techniques to detect seepage zones in river embankments. Geosciences 11(2):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences11020069

Höttges A, Rabaiotti C, Facchini M (2023) A novel distributed fiber optic hydrostatic pressure sensor for dike safety monitoring. IEEE Sens J. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2023.3315062

Huang AB, Mayne PW (Eds) (2008) Geotechnical and geophysical site char-acterization: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Site Characterization

Inazaki T, Sakamoto T (2005) Geotechnical characterization of levee by integrated geophysical surveying. In: Proceedings of the International Symposium on Dam Safety and Detection of Hidden Troubles of Dams and Dikes, pp 1–3

Johannson S, Sjodahl P, Burstedt J (2015) Process seepage monitoring system based on fibre-optic distributed temperature sensing at the tailings dams at Hotjarn, Sweden. In: Q.99-R.7, 20th Congress on Large Dam, Stavanger, Norway, 17–19 June 2015

Johansson S, Sjödahl P (2004) Downstream seepage detection using temperature measurements and visual inspection—monitoring experiences from Røsvatn field test dam and large embankment dams in Sweden. In: Proc. Intl. Seminar on Stability and Breaching of Embankment Dams, vol 21

Li F, Qin W, Hu H (2022) Experimental investigation monitoring the saturated line of slope based on distributed optical fiber temperature system. Adv Mater Sci Eng 2022. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/9243361

Oguz EA, Depina I, Myhre B, Devoli G, Rustad H, Thakur V (2022) IoT-based hydrological monitoring of water-induced landslides: a case study in central Norway. Bull Eng Geol Env 81(5):217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-022-02721-z

Perri MT, Boaga J, Bersan S, Cassiani G, Cola S, Deiana R, Simonini P, Patti S (2014) River embankment characterization: the joint use of geophysical and geotechnical techniques. J Appl Geophys 110:5–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jappgeo.2014.08.012

Pozzato A, Tarantino A, De Polo F (2020) Analysis of the effects of the partial saturation on the Adige River embankment stability. In: Unsaturated soils: research & applications. CRC Press, pp 1367–1372. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.1201/9781003070580-65/analysis-effects-partial-saturation-adigeriver-embankment-stability-pozzato-tarantino-de-polo?context=ubx

Radzicki K (2014) The thermal monitoring method–a quality change in the monitoring of seepage and erosion processes in dikes and earth dams. Modern monitoring solutions of dams and dikes. Hanoi, pp 33–41

Schenato L (2017) A review of distributed fiber optic sensors for geo-hydrological applications. Appl Sci 7(9):896

Schenato L, Fabbian N, Dalla Santa G, Simonini P, De Polo F, Tedesco G, Marcato G, Cola S (2022) Distributed optical fiber sensors for the soil temperature measurement in river embankments. In: 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Measurements & Networking (M&N). IEEE, pp 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/MN55117.2022.9887664

Sjödahl P, Dahlin T, Johansson S (2009) Embankment dam seepage evaluation from resistivity monitoring data. Near Surface Geophys 7(5–6):463–474. https://doi.org/10.3997/1873-0604.2009023

Su H, Kang Y (2013) Design of system for monitoring seepage of levee engineering based on distributed optical fiber sensing technology. Int J Distrib Sens Netw 9(12):358784

Su H, Hu J, Yang M (2014) Dam seepage monitoring based on distributed optical fiber temperature system. IEEE Sens J 15(1):9–13

Su H, Li H, Kang Y, Wen Z (2018) Experimental study on distributed optical fiber-based approach monitoring saturation line in levee engineering. Opt Laser Technol 99:19–29

Utili S, Castellanza R, Galli A, Sentenac P (2015) Novel approach for health monitoring of earthen embankments. J Geotech Geoenviron Eng 141(3). https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0001215

Ye X, Zhu HH, Wang J, Zhang Q, Shi B, Schenato L, Pasuto A (2022) Subsurface multi-physical monitoring of a reservoir landslide with the fiber-optic nerve system. Geophys Res Lett 49(11):e2022GL098211. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GL098211

Yusa M, Bowman ET, Cubrinovski M (2017) Observation of microstructure of silty sand obtained from gelpush sampler and reconstituted sample. In: EPJ Web of Conferences, vol 140. EDP Sciences, p 12017

Zhang Y, Xue Z (2019) Deformation-based monitoring of water migration in rocks using distributed fiber optic strain sensing: a laboratory study. Water Resour Res 55:8368–8383. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019WR024795

Zhou R, Wen Z, Su H (2022a) Detect submerged piping in river embankment by passive infrared thermography. Measurement 202:111873

Zhou Y, Liang C, Wang F, Zhao C, Zhang A, Tan T, Gong P (2022b) Field test and numerical simulation of the thermal insulation effect of concrete pouring block surface based on DTS. Constr Build Mater 343:128022

Zhu PY, Zhou Y, Thevenaz L, Jiang GL (2009) Seepage and settlement monitoring for earth embankment dams using fully distributed sensing along optical fibers. In: 2008 International Conference on Optical Instruments and Technology: Optoelectronic Measurement Technology and Applications, vol 7160. SPIE, pp 283–289

Zhu HH, Wu B, Cao DF, Li B, Wen Z, Liu XF, Shi B (2023) Characterizing thermo-hydraulic behaviors of seasonally frozen loess via a combined opto-electronic sensing system: field monitoring and assessment. J Hydrol 622:129647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.129647

Zwanenburg C, López-Acosta NP, Tourment R, Tarantino A, Pozzato A, Pinto A (2018) Lessons learned from dike failures in recent decades. Int J Geoeng Case Hist 4(3):203–229. https://doi.org/10.4417/IJGCH-04-03-04

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Padova.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

“Conceptualization, NF, PS, FDP, LS, and SC; methodology, NF, LS, and SC; software, NF and LS; validation, NF, LS, and SC; formal analysis, NF; investigation, NF; resources, NF; data curation, NF; writing—original draft preparation, NF; writing—review and editing, NF and SC; visualization, NF and SC; supervision, NF and SC; project administration, SC; funding acquisition, FDP and PS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fabbian, N., Simonini, P., De Polo, F. et al. Temperature monitoring in levees for detection of seepage. Bull Eng Geol Environ 83, 69 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-024-03566-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-024-03566-4