Abstract

This paper studies how in-group social connections affect outsiders’ pro-social behavior towards group members. We employ an indirect investment game, in which a recipient of a good deed has to return to a beneficiary, instead of the original donor. We introduce the naturally-occurring social connections between the donor and the beneficiary, and show that such connections increase the recipients’ transfer to a beneficiary by 42% when the donor’s transfer is above average. The spillover does not function through the signaling of the donor’s expectations, and altruism with an endogenous reference group explains our results well.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This situation is usually referred as a kind of indirect reciprocity in the literature. Previous works distinguish between upstream and downstream indirect reciprocity. In Nowak and Sigmund (2005) what we study in this paper is defined as “upstream reciprocity”. The downstream reciprocity refers to the case in which A helps B, and upon observing A’s behavior, C is willing to help A. Stanca (2009) also calls the case we study “generalized indirect reciprocity.” For simplicity, throughout this paper, we will refer to the behavior we studied as “indirect reciprocity.”.

Engelmann and Fischbacher (2009) conducted a multi-period repeated helping game similar to that of Nowak and Sigmund (1998) and Seinen and Schram (2006). In their design, the subjects’ history of play was private information in some rounds; thus, there was no strategic incentive to build a reputation. They also showed the existence of indirect reciprocity. Some papers study the evolutionary source of indirect reciprocity and how its effectiveness in supporting cooperation depends on factors such as group size (Boyd and Richerson, 1989; Greiner and Levati, 2005; Hamilton and Taborsky, 2005; van Doorn and Taborsky, 2012).

The classical form of investment started by Berg et al. (1995) has equal donations between donor and recipient. However, many other studies have also used unequal donations. For instance, Ashraf et al. (2006), when measuring trust and trustworthiness, conducted an investment game with unequal donations.

There were two sessions in the Connection and the Indirect treatments, respectively. Direct and Message treatments each has one session.

Interaction experience profoundly affect pro-social preferences (Bault et al. 2017) and in-group bias (Guo et al. 2020). After discussion with the instructors and members of the clubs, we confirmed that there were many regular group activities within each club. Thus, we could infer that club members were quite cohesive and formed close ties (Goette et al. 2012). The demographic characteristics of these two clubs were also similar.

Some members from these two clubs may know each other, hence there may exist naturally-occurring inter-group social connections. However, our focus is the return behavior of non-club participants, instead of the club members’ initial donation. Moreover, even if those non-club participants may infer inter-group social connections among club participants, they would be less likely to discriminate members from different clubs. This would only weaken the effect of in-group social connections, suggesting that the effects of social connections in our experiment underestimate the real magnitude of in-group social connections.

This is due to the practical issue to minimize the impatience of Ai in waiting for the results. Since Ai knew the status information after her decisions, this would not affect her behavior.

Though the difference is significant, they are all substantially lower than the transfer in the Direct Treatment. We think it might be due to that the Indirect Treatment was run in different time from the Connection and Message Treatment. However, since we focus on the behavior of recipient, and we control for the donor’s initial donation in the regression results, our analysis mainly addresses the within treatment difference, this difference is unlikely to affect the results.

The median value is also similar.

We have attempted the results with other thresholds, such as 5, 7, 8, respectively. The main results still hold.

We didn’t use clustered standard errors on the subject level, since it will cause too fewer clusters than the ideal number of clusters suggested by Angrist and Pischke (2008).

We also control for possible nonlinearity in the transfer-return relationship by adding the square term of Ai’s transfer, but this does not influence our treatment effect. We have run two separate sessions of the Connection Treatment, and the estimated treatment effects are the same within each session.

Following the suggestion of a referee, we also use the return ratio, e.g., Bi’s transfer/ (3 × Ai’s transfer), as an outcome variable. The results are reported in Appendix C. Though the sign of the interaction variable is positive, it is not statistically significant. It might be due to that in general the return ratio is higher in the Connection Treatment, as Table 3 shows. Moreover, Panel A in Table 3 also shows that the difference in return ratio across connection status is insignificant within the Connection Treatment.

It’s noteworthy that this is different from the results in Table 3, which shows that the ratios of donations are significantly higher in the Connection Treatment than the Indirect Treatment. It’s because Ai’s transfer is significantly lower in the Connection Treatment, while the difference in Bi’s transfer is insignificant between the Connection Treatment and the Indirect Treatment.

It is also possible that Bi expects to receive some positive amount, and any transfer below this amount will seem to be surprisingly bad and hence lead to a lower welfare weight for Ai, as well as for Ak, who is socially connected to Ai. However, our experimental results provide no evidence supporting that those who are socially connected to a completely selfish Ai (who transferred zero) are punished by the recipient. Perhaps since the lowest possible number a Bi could give is zero, the scope of punishment becomes limited.

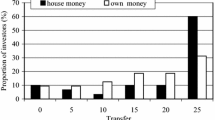

In a multiple choice question in the post-experimental questionnaire we ask the recipients about the motivation underlying her choice in experiments. The percentage of respondents is in the bracket: Q5. What’s the single most important reason underlying your decision to transfer to A in stage 2? A. I think A in stage 2 has less endowment than me, so I want to help him/her. This has nothing to do with how much I received in stage 1. (9%) B. Because I received help from A in stage 1, I should be nice to others. (35%) C. Because I received help from A in stage 1, I should be nice to A’s friends in particular. (38%) D. Others. (18%). Hence, 38% of B subjects in the Connection Treatment explicitly state that being nice to the donor’s friend is the single most important reason underlying his transfer decision.

Ellingsen et al. (2010) investigate guilt aversion in bilateral interactions, controlling for consensus effects, and concluded that guilt aversion appeared to play a relatively minor role in their experiments. Charness and Dufwenberg (2010) suggest that only free-form communication might affect the beliefs of the players.

References

Akerlof G, Kranton R (2000) Economics and Identity. Quart J Econ 115:715–753

Angrist JD, Pischke JS (2008) Mostly harmless econometrics: an Empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press, New Jersey

Ashraf N, Bohnet I, Piankov N (2006) Decomposing trust and trustworthiness. Exp Econ 9:193–208

Bahr G, Requate T (2014) Reciprocity and giving in a consecutive three-person dictator game with social interaction. German Econ Rev 15(3):374–392

Battigalli P, Dufwenberg M (2007) Guilt in games. Am Econ Rev 97(2):170–176

Bault N, Fahrenfort JJ, Pelloux B, Ridderinkhof KR, van Winden F (2017) An affective social tie mechanism: theory, evidence, and implications. J Econ Psychol 61:152–175

Berg J, Dickhaut J, McCabe K (1995) Trust, reciprocity, and social history. Games Econom Behav 10:122–142

Bohnet I, Frey B (1999) Social distance and other-regarding behavior in dictator games: comment. Am Econ Rev 89:335–339

Bolton G, Ockenfels A (2000) ERC: a theory of equity, reciprocity, and competition. Am Econ Rev 90:166–193

Boyd R, Richerson PJ (1989) The evolution of indirect reciprocity. Soc Netw 11(3):213–236

Buchan N, Croson R, Dawes R (2002) Swift neighbors and persistent strangers: a cross-cultural investigation of trust and reciprocity in social exchange. Am J Sociol 108:168–206

Buchan N, Croson R (2004) The boundaries of trust: own and others’ actions in the US and China. J Econ Behav Organ 55:485–504

Buchan N, Johnson EJ, Croson R (2006) Let’s get personal: an international examination of the influence of communication, culture and social distance on other regarding preferences. J Econ Behav Organ 60:373–398

Charness G, Rabin M (2002) Understanding social preferences with simple tests. Quart J Econ 117:817–869

Charness G, Dufwenberg M (2006) Promises and partnership. Econometrica 74:1579–1601

Charness G, Dufwenberg M (2010) Bare promises: an experiment. Econ Lett 107:281–283

Charness G, Gneezy U (2008) What’s in a name? anonymity and social distance in dictator and ultimatum games. J Econ Behav Organ 68:29–35

Charness G, Kuhn P (2010) Lab labor: what can labor economists learn from the lab? In: Ashenfelter O, Card D (eds) Handbook of labor economics. North-Holland, Amsterdam

Chen Y, Li SX (2009) Group identity and social preferences. Am Econ Rev 99:431–457

Currie J, Lin WC, Meng JJ (2013) Social networks and externalities from gift exchange: evidence from a field experiment. J Public Econ 107:19–30

Dufwenberg M, Gneezy U, Guth W, van Damme E (2001) Direct vs indirect reciprocity: an experiment. Homo Oeconomicus 43:19–30

Dufwenberg M, Kirchsteiger G (2004) A theory of sequential reciprocity. Games Econom Behav 47:268–298

Ellingsen T, Johannesson M, Torsvik G, Tjotta S (2010) Testing guilt aversion. Games Econom Behav 68:95–107

Engelmann D, Fischbacher U (2009) Indirect reciprocity and strategic reputation building in an experimental helping game. Games Econom Behav 67:399–407

Fehr E, Schmidt K (1999) A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. Quart J Econ 114:817–868

Goeree J, McConnel M, Mitchell T, Tromp T, Yariv L (2010) The 1/d law of giving. Am Econ J Microecon 2:183–203

Goette L, Huffman D, Meier S (2006) The impact of group membership on cooperation and norm enforcement: evidence using random assignment to real social groups. Am Econ Rev 96:212–216

Goette L, Huffman D, Meier S (2012) The impact of social ties on group interactions: evidence from minimal groups and randomly assigned real groups. Am Econ J Microecon 4:101–115

Granovetter M (1985) Economic action and social structure: the problem of embeddedness. Am J Sociol 91:481–510

Granovetter M (2005) The impact of social structure on economic outcomes. J Econ Perspect 19:33–50

Granovetter M (2017) Society and economy: framework and principles. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Gray K, Ward AF, Norton MI (2014) Paying it forward: generalized reciprocity and the limits of generosity. J Exp Psychol Gen 143(1):247–254

Greiner B, Levati MV (2005) Indirect reciprocity in cyclical networks: an experimental study. J Econ Psychol 26(5):711–731

Gul F, Pesendorfer W (2016) Interdependent preference models as a theory of intentions. J Econ Theory 165:179–208

Guo S, Liang P, Xiao E (2020) In-group bias in prisons. Games Econ Behav 122:328–340

Guth W, Konigstein M, Marchand N, Nehring K (2001) Trust and reciprocity in the investment game with indirect reward. Homo Oeconomicus 43:241–262

Hamilton IM, Taborsky M (2005) Contingent movement and cooperation evolve under generalized reciprocity. Proc Biol Sci 272(1578):2259

Hoffman E, McCabe K, Smith VL (1996) Social distance and other-regarding behavior in dictator games. Am Econ Rev 86:653–660

Hugh-Jones D, Leroch MA (2017) Intergroup revenge: a laboratory experiment on the causes. Homo Oeconomicus 34:117–135

Jackson M (2008) Social and economic networks. Princeton University Press, New Jersey

Kimbrough E, Rubin J (2015) Sustaining group reputation. J Law Econ Organ 31:599–628

Levine D (1998) Modeling altruism and spitefulness in experiment. Rev Econ Dyn 1:593–622

Li J, Cheo R, Xiao E (2020) The effect of voice on indirect reciprocity: results from the lab. Econ Lett 189:108988

Liang P, Meng J (2016) Favor transmission under social image concern: an experimental study. J Behav Exp Econ 63:14–21

Malmendier U, Schmidt KM (2017) You owe me. Am Econ Rev 107:493–526

Mujcic R, Leibbrandt A (2017) Indirect reciprocity and prosocial behaviour: evidence from a natural field experiment. Econ J 128:1683–1699

Nowak MA, Sigmund K (1998) Evolution of indirect reciprocity by image scoring. Nature 393:573–577

Nowak MA, Sigmund K (2005) Evolution of indirect reciprocity. Nature 437:1291–1298

Mueller HM, Philippon T (2011) Family firms and labor relations. Am Econ J Macroecon 3:218–245

Rabin M (1993) Incorporating fairness into game theory and economics. Am Econ Rev 83:1281–1302

Seinen I, Schram A (2006) Social status and group norms: indirect reciprocity in a helping experiment. Eur Econ Rev 50:581–602

Stanca L (2009) Measuring indirect reciprocity: whose back do we scratch? J Econ Psychol 30:190–202

Strassmair C (2009) Can intentions spoil the kindness of a gift?—An experimental study. Working Paper.

Song F, Cadsby CB, Bi YY (2012) Trust, reciprocity, and guanxi in China: an experimental investigation. Manag Organ Rev 8:397–421

Tajfel H, Turner JC (1986) The social identity theory of inter-group behavior. In: Worchel S, Austin LW (eds) Psychology of intergroup relations. Nelson-Hall, Chicago

Tirole J (1996) A theory of collective reputations (with applications to the persistence of corruption and to firm quality). Rev Econ Stud 63:1–22

van Doorn GS, Taborsky M (2012) The evolution of generalized reciprocity on social interaction networks. Evolution 66(3):651–664

van Dijk F, van Winden F (1997) Dynamics of social ties and local public good provision. J Public Econ 64:323–341

Van Winden F, Stallen M, Ridderinkhof KR (2008) On the nature, modeling, and neural bases of social ties. In: Houser D, McCabe K (eds) Advances in health economics and health services research 20, neuroeconomics. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, London

Acknowledgements

This paper replaces the previous version with the title “Love Me, Love My Friend: An Experimental Study on Social Connections and Indirect Reciprocity”. We are grateful for the valuable comments of Bram Cadsby, Colin Camerer, Jimmy Chan, Gary Charness, Ninghua Du, Daniel Houser, Changxia Ke, Wooyoung Lim, Tracy Xiao Liu, David Ong, Jason Shachat, Fei Song, Chun-lei Yang, as well as those of the attendants of CES (2013), ESCM (2013), seminars in SHUFE, SWUFE, Sun Yat-sen University, Tsinghua, and WISE (Xiamen). The excellent research assistant works conducted by Yuchen Guo and various students are acknowledged. Pinghan Liang acknowledges the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 71503208 and 71873149). Juanjuan Meng acknowledges the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 71103003 and 71471004), the Beijing Higher Education Young Elite Teacher Project (Grant No. YETP0040).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A: Experimental instructions

Below we provide the English translation of the experimental instructions for the Connection Treatment and indicate the differences in other treatments in the related places.

1.1 General instructions

Our general instructions read as follows:

“Welcome to our experiment! Here are some general instructions that require your special attention.

-

1.

You are required to obey the assistants’ instructions during the whole experiment. We will appreciate it if you could keep silence until leaving the room. Chatting with other participants is also forbidden. Please raise your hand and signal the assistants if you encounter any problem and we will solve your problems privately. Besides, during the experiment you are not allowed to leave the room for any reason, including receiving incoming calls and messages.

-

2.

Each participant will be assigned as either Role A or Role B. Participants with the same role will be staying in the same room.

-

3.

This experiment is PAYABLE.

You will be paid a specific amount after finishing this experiment. The payment consists of two parts—base payment and extra payment. Base payment is ¥25 for each participant. Extra payment is based on the outcome of the experiment. Please read carefully the EXPERIMENT GUIDELINES, which will help you make better decisions and maximize the payoff.

-

4.

This experiment guarantees ANONYMITY.

You will be matched with participants with a different role. The experiment consists of several rounds and you will be matched randomly with different participants in each round. Nobody will know who he/she is matched with. Besides, all participants’ behavior during the experiment is anonymous. The one matched with you couldn’t know who has made your decisions, and so do you.

-

5.

Your extra payment will be decided as below.

The experiment consists of several rounds. Your extra payment will be equal to your payoff in a particular round which is randomly picked up by computer software. That is to say, each round will have the same probability to be selected and thus decide your extra payment.

-

6.

This experiment guarantees your PRIVACY.

The privacy of your personal information and strategies during the experiment will be strictly guaranteed. You won’t be asked to provide your name and student ID during the whole experiment. Please stay on your seat and wait until the assistant delivers you an envelope with your payment inside. We also guarantee that you will be the only person who knows exactly how much you gain from the experiment.

-

7.

You will be given an EXPERIMENT GUIDELINES, a DRAFT PAPER and a PENCIL at the very beginning of the experiment. Please do all the computing on the draft and keep the Experiment Guidelines clean. You can leave the room after returning your Experiment Guidelines, draft papers and pencils to us.

Thank you for your participation!”

1.2 The experiment guidelines for player A

The Experiment Guidelines for Player A read as below:

“This experiment consists of FOUR PARTS.

Dear participant, you are going to play Role A in this experiment. Participants playing Role A will be assigned the same task, and so do those playing Role B. Participants playing the same role will be staying in the same room. You will be involved in several rounds of experiment, each round matching with one different Role B Players. In the experiment, each participant will be informed of nothing about other participants’ personal information except for their numbers.

-

1.

Part one—quick pre-test

Please read carefully the following guidelines. You are required to take a quick pre-test before taking the formal experiment. Basically you need to do some computation and figure out a number as the solution to each question. The pre-test aims at helping you understand how you will be paid in the experiment and so to make a reasonable strategy. Only after you pass the pre-test will you be permitted to take the formal experiment. The information needed to complete the pre-test will be shown afterwards, and you will be given the questions after finishing reading the entire experiment guidelines.

-

2.

Part two—formal experiment

The formal experiment will begin right after you pass the pre-test, and it consists of six rounds. Each round consists of three stages as shown below.

-

2.1.

Stage one

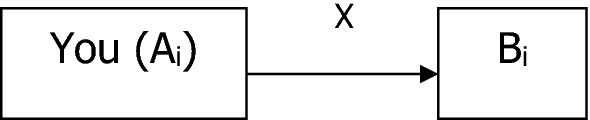

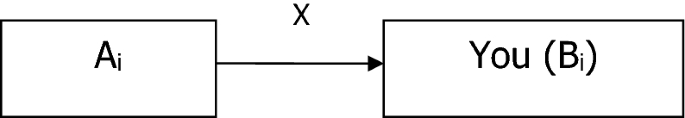

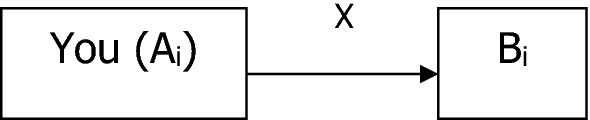

Suppose you are labeled as Ai in this round. You will be matched randomly with a Role B player Bi.

At the very beginning of this section, you will be given ¥30 while Bi will be given ¥10. Then you are requested to give ¥X to Bi (X can be a number within [0,30]) by filling the amount, i.e. X, in a particular part of the decision form, which will be enveloped and delivered to your experimental assistant. Afterwards, Bi’s assistant will receive the envelope and triple the amount, i.e. 3X, in another part of the form. That is exactly the amount Bi will get in this section.

For example, Bi will get ¥6 if you give him/her ¥2 and will get ¥27 if you give him/her ¥9.

-

2.2

Stage two

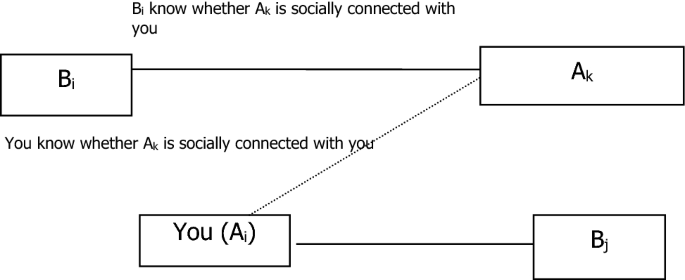

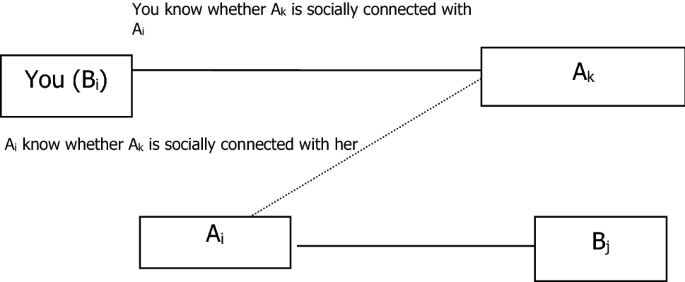

This section is simply a re-match. You will be matched randomly with another Role B player, say, Bj. And your former matched player, say, Bi, will be matched with another Role A player, say, Ak.

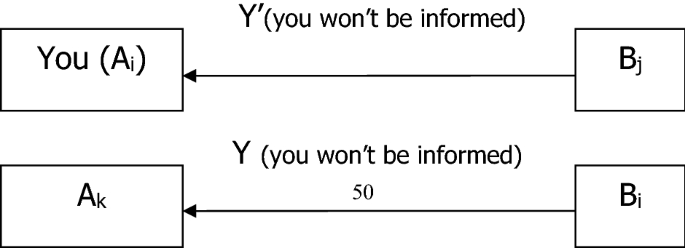

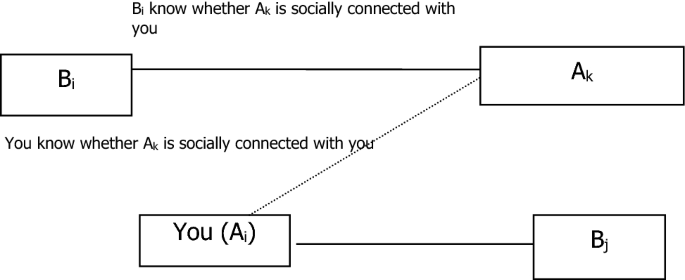

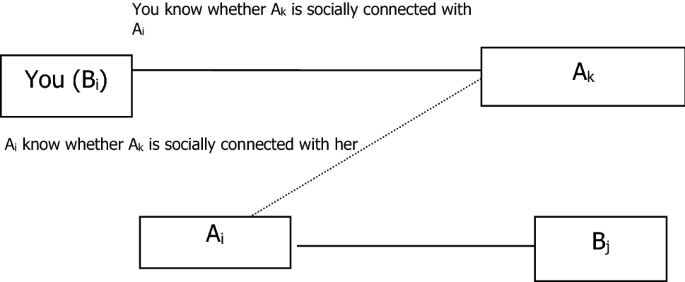

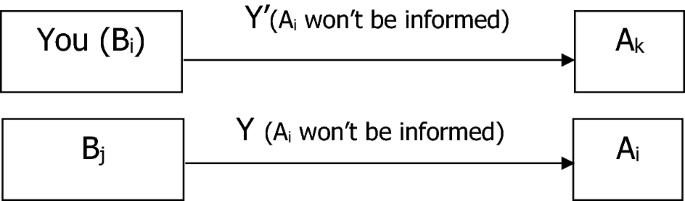

You and B i will both know whether you and A k are socially connected at this stage. But A k will not know.[In Indirect Treatment, there is no such statement. In Message Treatment, the instruction here says “After the re-match, you’ll be given a choice whether to leave a message to B i or not. Two notes will be delivered to you, one written with PLEASE BE KIND TO A k and the other simply being blank. You can choose one of the notes and hand it to the assistant, who will help you deliver it to B i . One thing to notice is that, you will have to pay ¥1 if you choose to leave a message. Meanwhile, A k doesn’t know whether you have left a message or not.” Corresponding changes in the figure illustration will be made.]

-

2.3

Stage Three

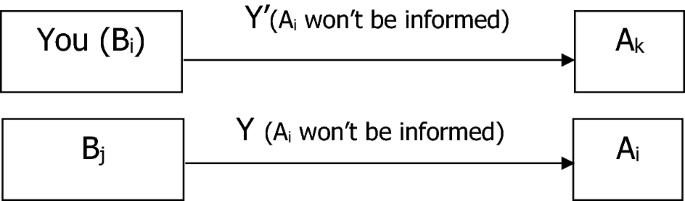

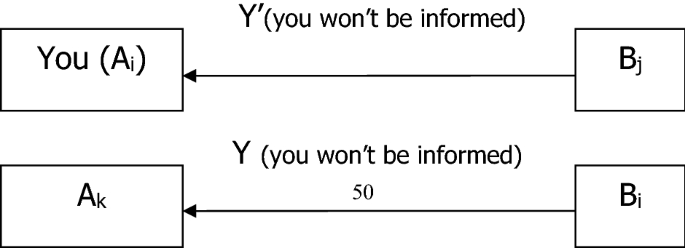

In this stage, Bi is requested to give ¥Y to Ak while Bj is requested to give ¥Y’ to you. You won’t be informed of the exact amount of either Y or Y’.

-

2.4.

An example to calculate the payoff

Suppose you give ¥X to Bi in stage one, Bi gives ¥Y to Ak in stage three and Bj gives you ¥Y’ also in stage three. Then your payoff will be ¥ (30-X + Y’) and Bi’s payoff will be ¥ (10 + 3X−Y).

-

2.1.

-

3.

Part Three –Questionnaire on Your Personal Information

After the formal experiment, you are required to take a questionnaire merely used for our academic research. We will strictly guarantee the security of your personal information and nobody else will get access to it. We will appreciate it if you could provide us with your information and ideas after serious ponder. Any information you provide could not be revised once settled.

-

4.

Part Four—Gain Your Payoff for this Experiment

Having finished the three parts ahead, your assistant will deliver you an envelope with your payment for this experiment. The payment will be based on the outcome of one round randomly picked from the six. You are the only person who knows your exact payment.Please stay on your seat and wait until the assistant delivers you the envelope. Then you can leave the room after returning your experiment guidelines, draft papers, and pencils to us.

1.3 The experiment guidelines for player B

The Experiment Guidelines for Player B read as below:

“This experiment consists of FOUR PARTS.

Dear participant, you are going to play Role B in this experiment. Participants playing Role B will be assigned the same task, and so do those playing Role A. Participants playing the same role will be staying in the same room. You will be involved in several rounds of experiment, each round matching with one different Role A Players. In the experiment, each participant will be informed of nothing about other participants’ personal information except for their numbers.

-

1.

Part One—Quick Pre-test

The same as Part 1 in Sect. 1.2.

-

2.

Part Two –Formal Experiment

The formal experiment will begin right after you pass the pre-test, and it consists of six rounds. Each round consists of three stages as shown below.

-

2.1

Stage One

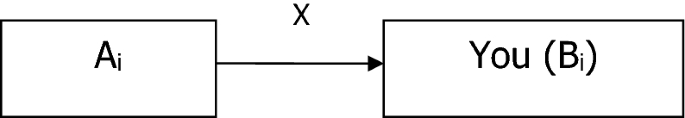

Suppose you are labeled as Bi in this round. You will be matched randomly with a Role A playerAi.

-

2.2

Stage Two

This stage is simply a re-match. You will be matched randomly with another Role A player, say, Ak. And your former matched player, say, Ai, will be matched with another Role B player, say, Bj.

Both you and Ai will be informed whether Ai and Ak are socially connected at this stage, but Ak doesn’t know it. [In Indirect Treatment, there is no such statement. In Message Treatment, the instruction here says “After the re-match, Ai will be given a choice whether to leave a message to you or not. Two paper notes will be delivered to Ai, one written with PLEASE BE KIND TO Ak and the other simply written with nothing. Ai can choose one of the paper notes and hand it to the assistant, who will help you deliver it to you. One thing to notice is that, Ai will have to pay ¥1 if he/she chooses to leave a message. Meanwhile, Ak couldn’t know whether Ai has left a message or not.” Corresponding changes in the figure illustration will be made.]

-

2.3

Stage Three

In this stage, Bj is requested to give ¥Y to Ai while you are requested to give ¥Y’ to Ak. Ai won’t be informed of the exact amount of either Y or Y’.

-

2.4

An example to calculate the payoff

Suppose Ai gives ¥X to you in stage one, Bj gives ¥Y to Ai in stage three and you give Ak¥Y’ also in stage three. Then Ai’s payoff will be ¥ (30-X + Y) and your payoff will be ¥ (10 + 3X-Y’).

-

2.1

-

3.

Part Three –Questionnaire on Your Personal Information

The same as Part 3 in Sect. 1.2.

-

4.

Part Four—Gain Your Payoff for this Experiment

The same as Part 4 in Sect. 1.2.”

Appendix B: Direct vs. indirect treatment

We compared the results of the standard investment game in the bilateral interaction (Direct Treatment) with the indirect reciprocity to a third party (Indirect Treatment). To keep the design consistent, we used only the Indirect Treatment without the club introduction stage (I2) before the experiment. However, as the introduction of the club did not generate any difference in the Indirect Treatment, the results were always the same whether I1 or I2 was used. Summary statistics have already suggested that Ai tends to give substantially more in direct interactions, which naturally leads to more transfer from Bi. However, our focus was on Bi’s transfer behavior after controlling for Ai’s initial transfer.

Table B1 reports a set of regressions on this issue. We pooled Bi’s transfers from the Direct and Indirect Treatments (session I2) together, and regressed it against Ai’s transfer, a dummy variable indicating whether the observation was from the Indirect Treatment (I2), the interaction of the previous two terms, and five round dummy variables. Because different treatments contain different subjects, subjects fixed effect cannot be used if we want to estimate the difference between treatments, so we use random effect clustered at the subject level. We report both the random effect model (Columns (1) and (2)) to analyze the effect of explanatory variables on the mean of Bi’s transfer, as well as the quantile regression (Columns (3) and (4)) to understand the effect on the median value of Bi’s transfer. Since quantile (e.g., median) is not subject to strong influence from extreme outliers in explanatory variables, this method may deliver more robust estimates given our relatively small sample size.

We observed very strong and positive monotonic effects of Ai’s transfer on both the mean and median of Bi’s transfer amount. However, controlling for Ai’s transfer, there were no statistically significant differences across the two treatments in either the level of Bi’s transfer or its slope associated with Ai’s transfer. These results suggest that there was no fundamental difference in Bi’s return behavior except those with respect to the level of Ai’s initial transfer, despite the fact that Bi made payment back to an unrelated third party in the Indirect Treatment. Bi’s incentive to reciprocate or help others after being treated well by Ai did not seem to be restricted to the bilateral relationship (see Table 7).

Appendix C: Results with the return ratio as the dependent variable

See Table 8.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, P., Meng, J. Paying it forward: an experimental study on social connections and indirect reciprocity. Rev Econ Design 27, 387–417 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10058-022-00298-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10058-022-00298-3